From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

In

physics,

relativistic mechanics refers to

mechanics compatible with

special relativity (SR) and

general relativity (GR). It provides a non-

quantum mechanical description of a system of particles, or of a

fluid, in cases where the

velocities of moving objects are comparable to the

speed of light c. As a result,

classical mechanics is extended correctly to particles traveling at high velocities and energies, and provides a consistent inclusion of

electromagnetism

with the mechanics of particles. This was not possible in Galilean

relativity, where it would be permitted for particles and light to

travel at

any speed, including faster than light. The foundations of relativistic mechanics are the

postulates of special relativity and general relativity. The unification of SR with quantum mechanics is

relativistic quantum mechanics, while attempts for that of GR is

quantum gravity, an

unsolved problem in physics.

As with classical mechanics, the subject can be divided into "

kinematics"; the description of motion by specifying

positions, velocities and

accelerations, and "

dynamics"; a full description by considering

energies,

momenta, and

angular momenta and their

conservation laws, and

forces

acting on particles or exerted by particles. There is however a

subtlety; what appears to be "moving" and what is "at rest"—which is

termed by "

statics" in classical mechanics—depends on the relative motion of

observers who measure in

frames of reference.

Although some definitions and concepts from classical mechanics do carry over to SR, such as force as the

time derivative of momentum (

Newton's second law), the

work done by a particle as the

line integral of force exerted on the particle along a path, and

power

as the time derivative of work done, there are a number of significant

modifications to the remaining definitions and formulae. SR states that

motion is relative and the laws of physics are the same for all

experimenters irrespective of their

inertial reference frames. In addition to modifying notions of

space and time, SR forces one to reconsider the concepts of

mass,

momentum, and

energy all of which are important constructs in

Newtonian mechanics.

SR shows that these concepts are all different aspects of the same

physical quantity in much the same way that it shows space and time to

be interrelated. Consequently, another modification is the concept of

the

center of mass of a system, which is straightforward to define in classical mechanics but much less obvious in relativity – see

relativistic center of mass for details.

The equations become more complicated in the more familiar

three-dimensional vector calculus formalism, due to the

nonlinearity in the

Lorentz factor, which accurately accounts for relativistic velocity dependence and the

speed limit of all particles and fields. However, they have a simpler and elegant form in

four-dimensional

spacetime, which includes flat

Minkowski space (SR) and

curved spacetime (GR), because three-dimensional vectors derived from space and scalars derived from time can be collected into

four vectors, or four-dimensional

tensors.

However, the six component angular momentum tensor is sometimes called a

bivector because in the 3D viewpoint it is two vectors (one of these,

the conventional angular momentum, being an

axial vector).

Relativistic kinematics

The relativistic four-velocity, that is the four-vector representing velocity in relativity, is defined as follows:

In the above, τ is the

proper time of the path through

spacetime, called the world-line, followed by the object velocity the above represents, and

is the

four-position; the coordinates of an

event. Due to

time dilation,

the proper time is the time between two events in a frame of reference

where they take place at the same location. The proper time is related

to

coordinate time t by:

where γ(

v) is the

Lorentz factor:

(either version may be quoted) so it follows:

The first three terms, excepting the factor of γ(

v), is the velocity as seen by the observer in their own reference frame. The γ(

v) is determined by the velocity

v

between the observer's reference frame and the object's frame, which is

the frame in which its proper time is measured. This quantity is

invariant under Lorentz transformation, so to check to see what an

observer in a different reference frame sees, one simply multiplies the

velocity four-vector by the Lorentz transformation matrix between the

two reference frames.

Relativistic dynamics

Relativistic energy and momentum

There are a couple of (equivalent) ways to define momentum and energy in SR. One method uses

conservation laws. If these laws are to remain valid in SR they must be true in every possible reference frame. However, if one does some simple

thought experiments

using the Newtonian definitions of momentum and energy, one sees that

these quantities are not conserved in SR. One can rescue the idea of

conservation by making some small modifications to the definitions to

account for

relativistic velocities. It is these new definitions which are taken as the correct ones for momentum and energy in SR.

The

four-momentum of an object is straightforward, identical in form to the classical momentum, but replacing 3-vectors with 4-vectors:

The energy and momentum of an object with

invariant mass m0 (also called

rest mass), moving with

velocity v with respect to a given frame of reference, are respectively given by

The factor of γ(

v) comes from the definition of the

four-velocity described above. The appearance of the γ factor has an

alternative way of being stated, explained in the next section.

The kinetic energy,

K, is defined as

And the speed as a function of kinetic energy is given by

Rest mass and relativistic mass

The quantity

is often called the

relativistic mass of the object in the given frame of reference.

[1]

This makes the relativistic relation between the spatial velocity and

the spatial momentum look identical. However, this can be misleading,

as it is

not appropriate in special relativity in

all

circumstances. For instance, kinetic energy and force in special

relativity can not be written exactly like their classical analogues by

only replacing the mass with the relativistic mass. Moreover, under

Lorentz transformations, this relativistic mass is not invariant, while

the rest mass is. For this reason many people find it easier use the

rest mass (thereby introduce γ through the 4-velocity or coordinate

time), and discard the concept of relativistic mass.

Lev B. Okun suggested that "this terminology ... has no rational justification today", and should no longer be taught.

[2]

Other physicists, including

Wolfgang Rindler and

T. R. Sandin, have argued that relativistic mass is a useful concept and there is little reason to stop using it.

[3] See

mass in special relativity for more information on this debate.

Some authors use

m for relativistic mass and

m0 for rest mass,

[4] others simply use

m for rest mass. This article uses the former convention for clarity.

The energy and momentum of an object with invariant mass

m0 are related by the formulas

The first is referred to as the

relativistic energy–momentum relation. It can be derived by considering that

can be written as

where the denominator can be written as

. Now, gamma can be replaced in the expression of energy. While the energy

E and the momentum

p depend on the frame of reference in which they are measured, the quantity

E2 − (

pc)

2 is invariant, and arises as −

c2 times the squared magnitude of the

4-momentum vector which is −(

m0c)

2.

It should be noted that the invariant mass of a system

is different from the sum of the rest masses of the particles of

which it is composed due to kinetic energy and binding energy. Rest mass

is not a conserved quantity in special relativity unlike the situation

in Newtonian physics. However, even if an object is changing internally,

so long as it does not exchange energy with surroundings, then its rest

mass will not change, and can be calculated with the same result in any

frame of reference.

A particle whose rest mass is zero is called

massless.

Photons and

gravitons are thought to be massless; and

neutrinos are nearly so.

Mass–energy equivalence

The relativistic energy–momentum equation holds for all particles, even for

massless particles for which

m0 = 0. In this case:

When substituted into

Ev =

c2p, this gives

v =

c: massless particles (such as

photons) always travel at the speed of light.

Notice that the rest mass of a composite system will generally be

slightly different from the sum of the rest masses of its parts since,

in its rest frame, their kinetic energy will increase its mass and their

(negative) binding energy will decrease its mass. In particular, a

hypothetical "box of light" would have rest mass even though made of

particles which do not since their momenta would cancel.

Looking at the above formula for invariant mass of a system, one sees that, when a single massive object is at rest (

v =

0,

p =

0), there is a non-zero mass remaining:

m0 =

E/

c2.

The corresponding energy, which is also the total energy when a single

particle is at rest, is referred to as "rest energy". In systems of

particles which are seen from a moving inertial frame, total energy

increases and so does momentum. However, for single particles the rest

mass remains constant, and for systems of particles the invariant mass

remain constant, because in both cases, the energy and momentum

increases subtract from each other, and cancel. Thus, the invariant mass

of systems of particles is a calculated constant for all observers, as

is the rest mass of single particles.

The mass of systems and conservation of invariant mass

For systems of particles, the energy–momentum equation requires summing the momentum vectors of the particles:

The inertial frame in which the momenta of all particles sums to zero is called the

center of momentum frame. In this special frame, the relativistic energy–momentum equation has

p = 0, and thus gives the invariant mass of the system as merely the total energy of all parts of the system, divided by

c2

This is the invariant mass of any system which is measured in a frame

where it has zero total momentum, such as a bottle of hot gas on a

scale. In such a system, the mass which the scale weighs is the

invariant mass, and it depends on the total energy of the system. It is

thus more than the sum of the rest masses of the molecules, but also

includes all the totaled energies in the system as well. Like energy and

momentum, the invariant mass of isolated systems cannot be changed so

long as the system remains totally closed (no mass or energy allowed in

or out), because the total relativistic energy of the system remains

constant so long as nothing can enter or leave it.

An increase in the energy of such a system which is caused by translating the system to an inertial frame which is not the

center of momentum frame, causes an increase in energy and momentum without an increase in invariant mass.

E =

m0c2, however, applies only to isolated systems in their center-of-momentum frame where momentum sums to zero.

Taking this formula at face value, we see that in relativity, mass is

simply energy by another name (and measured in different units). In

1927 Einstein remarked about special relativity, "Under this theory mass

is not an unalterable magnitude, but a magnitude dependent on (and,

indeed, identical with) the amount of energy."

[5]

Closed (isolated) systems

In a "totally-closed" system (i.e.,

isolated system)

the total energy, the total momentum, and hence the total invariant

mass are conserved. Einstein's formula for change in mass translates to

its simplest Δ

E = Δ

mc2 form, however, only in

non-closed systems in which energy is allowed to escape (for example, as

heat and light), and thus invariant mass is reduced. Einstein's

equation shows that such systems must lose mass, in accordance with the

above formula, in proportion to the energy they lose to the

surroundings. Conversely, if one can measure the differences in mass

between a system before it undergoes a reaction which releases heat and

light, and the system after the reaction when heat and light have

escaped, one can estimate the amount of energy which escapes the system.

Chemical and nuclear reactions

In

both nuclear and chemical reactions, such energy represents the

difference in binding energies of electrons in atoms (for chemistry) or

between nucleons in nuclei (in atomic reactions). In both cases, the

mass difference between reactants and (cooled) products measures the

mass of heat and light which will escape the reaction, and thus (using

the equation) give the equivalent energy of heat and light which may be

emitted if the reaction proceeds.

In chemistry, the mass differences associated with the emitted energy are around 10

−9 of the molecular mass.

[6]

However, in nuclear reactions the energies are so large that they are

associated with mass differences, which can be estimated in advance, if

the products and reactants have been weighed (atoms can be weighed

indirectly by using atomic masses, which are always the same for each

nuclide).

Thus, Einstein's formula becomes important when one has measured the

masses of different atomic nuclei. By looking at the difference in

masses, one can predict which nuclei have stored energy that can be

released by certain

nuclear reactions, providing important information which was useful in the development of nuclear energy and, consequently, the

nuclear bomb. Historically, for example,

Lise Meitner

was able to use the mass differences in nuclei to estimate that there

was enough energy available to make nuclear fission a favorable process.

The implications of this special form of Einstein's formula have thus

made it one of the most famous equations in all of science.

Center of momentum frame

The equation

E =

m0c2 applies only to isolated systems in their

center of momentum frame. It has been popularly misunderstood to mean that mass may be

converted to energy, after which the

mass

disappears. However, popular explanations of the equation as applied to

systems include open (non-isolated) systems for which heat and light

are allowed to escape, when they otherwise would have contributed to the

mass (

invariant mass) of the system.

Historically, confusion about mass being "converted" to energy has been aided by confusion between mass and "

matter", where matter is defined as

fermion

particles. In such a definition, electromagnetic radiation and kinetic

energy (or heat) are not considered "matter". In some situations, matter

may indeed be converted to non-matter forms of energy (see above), but

in all these situations, the matter and non-matter forms of energy still

retain their original mass.

For isolated systems (closed to all mass and energy exchange), mass

never disappears in the center of momentum frame, because energy cannot

disappear. Instead, this equation, in context, means only that when any

energy is added to, or escapes from, a system in the center-of-momentum

frame, the system will be measured as having gained or lost mass, in

proportion to energy added or removed. Thus, in theory, if an atomic

bomb were placed in a box strong enough to hold its blast, and detonated

upon a scale, the mass of this closed system would not change, and the

scale would not move. Only when a transparent "window" was opened in the

super-strong plasma-filled box, and light and heat were allowed to

escape in a beam, and the bomb components to cool, would the system lose

the mass associated with the energy of the blast. In a 21 kiloton bomb,

for example, about a gram of light and heat is created. If this heat

and light were allowed to escape, the remains of the bomb would lose a

gram of mass, as it cooled. In this thought-experiment, the light and

heat carry away the gram of mass, and would therefore deposit this gram

of mass in the objects that absorb them.

[7]

Angular momentum

In relativistic mechanics, the time-varying mass moment

and orbital 3-angular momentum

of a point-like particle are combined into a four-dimensional

bivector in terms of the 4-position

X and the 4-momentum

P of the particle:

[8][9]

where ∧ denotes the

exterior product.

This tensor is additive: the total angular momentum of a system is the

sum of the angular momentum tensors for each constituent of the system.

So, for an assembly of discrete particles one sums the angular momentum

tensors over the particles, or integrates the density of angular

momentum over the extent of a continuous mass distribution.

Each of the six components forms a conserved quantity when aggregated

with the corresponding components for other objects and fields.

Force

In special relativity,

Newton's second law does not hold in the form

F =

ma, but it does if it is expressed as

where

p = γ(

v)

m0v is the momentum as defined above and

m0 is the

invariant mass. Thus, the force is given by

Consequently, in some old texts, γ(

v)

3m0 is referred to as the

longitudinal mass, and γ(

v)

m0 is referred to as the

transverse mass, which is numerically the same as the

relativistic mass. See

mass in special relativity.

If one inverts this to calculate acceleration from force, one gets

The force described in this section is the classical 3-D force which is not a

four-vector. This 3-D force is the appropriate concept of force since it is the force which obeys

Newton's third law of motion. It should not be confused with the so-called

four-force

which is merely the 3-D force in the comoving frame of the object

transformed as if it were a four-vector. However, the density of 3-D

force (linear momentum transferred per unit

four-volume)

is a four-vector (

density of weight +1) when combined with the negative of the density of power transferred.

Torque

The

torque acting on a point-like particle is defined as the derivative of

the angular momentum tensor given above with respect to proper time:

[10][11]

or in tensor components:

where

F is the 4d force acting on the particle at the event

X. As with angular momentum, torque is additive, so for an extended object one sums or integrates over the distribution of mass.

Kinetic energy

The

work-energy theorem says

[12] the change in

kinetic energy is equal to the work done on the body. In special relativity:

![{\begin{aligned}\Delta K=W=[\gamma _{1}-\gamma _{0}]m_{0}c^{2}.\end{aligned}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/bc89ae0cb8f161d560e2900fbe6968467fc8742a)

If in the initial state the body was at rest, so

v0 = 0 and γ

0(

v0) = 1, and in the final state it has speed

v1 =

v, setting γ

1(

v1) = γ(

v), the kinetic energy is then;

![K=[\gamma (v)-1]m_{0}c^{2}\,,](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/e46c795b5262cc66c64992a6ccdaf1f71cdbe677)

a result that can be directly obtained by subtracting the rest energy

m0c2 from the total relativistic energy γ(

v)

m0c2.

Newtonian limit

The Lorentz factor γ(

v) can be expanded into a

Taylor series or

binomial series for (

v/

c)

2 < 1, obtaining:

and consequently

For velocities much smaller than that of light, one can neglect the terms with

c2 and higher in the denominator. These formulas then reduce to the standard definitions of Newtonian

kinetic energy and momentum. This is as it should be, for special relativity must agree with Newtonian mechanics at low velocities.

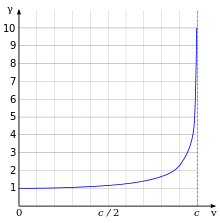

(ordinate) is equal to

(ordinate) is equal to  but as

but as  the

the  goes to infinity.

goes to infinity. (ordinate) is equal to

(ordinate) is equal to  but as

but as  the

the  goes to infinity.

goes to infinity. are the electron rest mass, velocity of the electron, and speed of light

respectively. The figure at the right illustrates the relativistic

effects on the mass of an electron as a function of its velocity.

are the electron rest mass, velocity of the electron, and speed of light

respectively. The figure at the right illustrates the relativistic

effects on the mass of an electron as a function of its velocity. ) which is given by

) which is given by is the reduced Planck's constant and α is the fine-structure constant (a relativistic correction for the Bohr model).

is the reduced Planck's constant and α is the fine-structure constant (a relativistic correction for the Bohr model). is the principal quantum number and Z is an integer for the atomic number. From quantum mechanics the angular momentum is given as

is the principal quantum number and Z is an integer for the atomic number. From quantum mechanics the angular momentum is given as  . Substituting into the equation above and solving for

. Substituting into the equation above and solving for  gives

gives and a high value of

and a high value of  that

that  .

This fits with intuition: electrons with lower principal quantum

numbers will have a higher probability density of being nearer to the

nucleus. A nucleus with a large charge will cause an electron to have a

high velocity. A higher electron velocity means an increased electron

relativistic mass, as a result the electrons will be near the nucleus

more of the time and thereby contract the radius for small principal

quantum numbers.[10]

.

This fits with intuition: electrons with lower principal quantum

numbers will have a higher probability density of being nearer to the

nucleus. A nucleus with a large charge will cause an electron to have a

high velocity. A higher electron velocity means an increased electron

relativistic mass, as a result the electrons will be near the nucleus

more of the time and thereby contract the radius for small principal

quantum numbers.[10]

![{\begin{aligned}\Delta K=W=[\gamma _{1}-\gamma _{0}]m_{0}c^{2}.\end{aligned}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/bc89ae0cb8f161d560e2900fbe6968467fc8742a)

![K=[\gamma (v)-1]m_{0}c^{2}\,,](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/e46c795b5262cc66c64992a6ccdaf1f71cdbe677)