Major depressive disorder is heavily influenced by environmental and genetic factors. These factors include epigenetic modification of the genome in which there is a persistent change in gene expression without a change in the actual DNA sequence. Genetic and environmental factors can influence the genome throughout a life; however, an individual is most susceptible during childhood. Early life stresses that could lead to major depressive disorder include periodic maternal separation, child abuse, divorce, and loss. These factors can result in epigenetic marks that can alter gene expression and impact the development of key brain regions such as the hippocampus. Epigenetic factors, such as methylation, could serve as predictors for the effectiveness of certain antidepressant treatments. Currently, antidepressants can be used to stabilize moods and decrease global DNA methylation levels, but they could also be used to determine the risk of depression caused by epigenetic changes. Identifying gene with altered expression could result in new antidepressant treatments.

Epigenetic alterations in depression

Histone deacetylases

Histone deacetylases (HDACs) are a class of enzymes that remove acetyl groups from histones. Different HDACs play different roles in response to depression, and these effects often vary in different parts of the body. In the nucleus accumbens (NaC), it is generally found that H3K14 acetylation decreases after chronic stress (used to produce a depression-like state in rodent model systems). However, after a while, this acetylation begins to increase again, and is correlated with a decrease in the activity and production of HDAC2. Adding HDAC2i (an HDAC2 inhibitor) leads to an improvement of the symptoms of depression in animal model systems. Furthermore, mice with a dominant negative HDAC2 mutation, which suppresses HDAC2 enzymatic activity, generally show less depressive behavior than mice who do not have this dominant negative mutation. HDAC5 shows the opposite trend in the NaC. A lack of HDAC5 leads to an increase in depressive behaviors. This is thought to be due to the fact that HDAC2 targets have antidepressant properties, while targets of HDAC5 have depressant properties.

In the hippocampus, there is a correlation between decreased acetylation and depressive behavior in response to stress. For example, H3K14 and H4K12 acetylation was found to be decreased, as well as general acetylation across histones H2B and H3. Another study found that HDAC3 was decreased in individuals resilient to depression. In the hippocampus, increased HDAC5 was found with increased depressive behavior (unlike in the nucleus accumbens).

Histone methyltransferases

Like HDACs, histone methyltransferases (HMTs) alter histones, but these enzymes are involved in the transfer of methyl groups to the histone's arginine and lysine residues. Chronic stress has been found to decrease the levels of a number of HMTs, such as G9a, in the NAc of susceptible mice. Conversely, in resilient mice, these HMTs have increased activity. H3K9 and H3K27 have less methylation when depressive behavior is seen. The hippocampus also experiences a number of histone methylation changes: H3K27-trimethylation is hypomethylated in response to stress, while H3K9-trimethylation and H3K4-trimethylation are hypermethylated in response to short term stress. However, H3K9-trimethylation and H3K4-trimethylation can also be hypomethylated in response to chronic, long term stress. In general, stress leading to depression is correlated with a decrease in methylation and a decrease in the activity of HMTs.

Brain-derived neurotrophic factor

Brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) is a neurotrophic growth factor that plays an important role in memory, learning, and higher thinking. It has been found that BDNF plasma levels and hippocampal volume are decreased in individuals suffering from depression. The expression of BDNF can be affected by different epigenetic modifications, and BDNF promoters can be individually regulated by different epigenetic alterations. MeCP2 can act as a repressor and has been shown to regulate BDNF when activated. Depolarization of neurons causing an increase in calcium leads to the phosphorylation of MeCP2, which results in a decrease in the binding of MeCP2 to BDNF promoter IV. Because MeCP2 can no longer bind to the BDNF promoter and repress transcription, BDNF levels increase and neuronal development improves. When there is direct methylation of the BDNF promoter, transcription of BDNF is repressed. Stressful situations have been shown to cause increased methylation of BDNF promoter IV, which causes an increase in MeCP2 binding, and as a result reduction in the activity of BDNF in the hippocampus and depressive behavior. BDNF maintains the survival of neurons in the hippocampus, and decreased levels can cause hippocampal atrophy. Also, there was found to be increased methylation of BDNF region IV CpGs in the Wernicke area of the brain in suicidal individuals. The interaction of BDNF and MeCP2 is complex, and there are instances where MeCP2 can cause an increase in BDNF levels instead of repressing. Previous studies have found that in MeCP2 knockout mice, the release and trafficking of BDNF within the neurons are significantly decreased in the hippocampus. Another epigenetic modification of BDNF promoters is the neuron-restrictive silencing factor (REST or NRSF) which epigenetically regulates the BDNF promoter I and is repressed by MeCP2. Like MeCP2, REST has also been found to inhibit BDNF transcription.

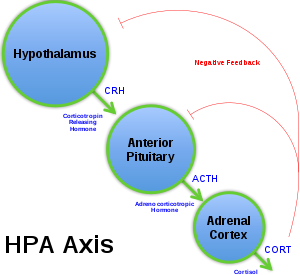

Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis

In the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis (HPA Axis), corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF) is secreted by the hypothalamus in response to stress and other normal body processes. CRH then acts on the anterior pituitary and causes it to secrete adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH). ACTH acts on the adrenal cortex to secrete cortisol, which acts as a negative feedback indicator of the pathway. When an individual is exposed to stressful situations, the HPA axis activates the sympathetic nervous system and also increases the production of CRF, ACTH, and cortisol, which in turn increases blood glucose levels and suppresses the immune system. Increased expression of CRF has been found in the cerebrospinal fluid in depressed monkeys and rats, as well as individuals with depression. Increased CRF levels have also been seen in the hypothalamus of depressed individuals. It was found that pregnant mice in early gestation stage who were exposed to chronic stress produced offspring with a decreased methylation of the CRF promoter in the hypothalamus area. This decreased methylation would cause increased expression of CRF and thus, increased activity of the HPA axis. The higher levels of the HPA axis in response to chronic stress can also cause damage to the hippocampus region of the brain. Increased cortisol levels can lead to a decrease in hippocampal volume which is commonly seen in depressed individuals.

Glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor

Glial cell-derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF) is a protein that aids in the survival and differentiation of dopaminergic neurons. By looking at expression levels in the nucleus accumbens, it is seen that GDNF expression is decreased in strains of mice susceptible to depression. It has also been shown that increased GDNF expression in the ventral tegmental area is present in mice that are not susceptible to social defeat stress by promoting the survival of neurons. The ventral tegmental area and nucleus accumbens network of the mesolimbic dopamine system is thought to be involved in the resistance and susceptibility to chronic stress (which leads to depressed behavior). Thus it is seen that GDNF, by protecting neurons of the mesolimbic pathway, helps to protect against depressive behavior. After chronic stress, there are a number of changes that result in the reduction of GDNF levels in the nucleus accumbens. This decrease is associated with decreased H3 acetylation and decreased H3K4-trimethylation, as well as an increased amount of DNA methylation at particular CpG sites on the GDNF promoter. This DNA methylation is associated with histone deacetylase 2 and methyl CpG binding protein 2 (MeCP2) recruitment to the GDNF promoter. Increased HDAC activity results in a reduction of GDNF expression, since HDAC causes the decreased acetylation at H3. Alternatively, knocking out HDACs (via HDAC interference) results in normalization of GDNF levels, and as a result, decreased depression like behavior, even in susceptible strains of mice. Cyclic-AMP response element-binding protein (CREB), which is thought to be involved in GDNF regulation, associates with the aforementioned MeCP2, and complexes to methylated CpG sites on the GDNF promoter. This recruitment of CREB plays a role in the repression of GDNF in the nucleus accumbens. As further evidence that DNA methylation plays a role in depressive behavior, delivery of DNA methyltransferase inhibitors results in a reversal of depression-like behaviors.

It is seen that DNA methylation of the GDNF promoter region results in the recruitment of MeCP2 and HDACs, resulting in an epigenetic alteration of the histone marks. This correlates to an increase in depression-like behavior.

Glucocorticoid receptor

Glucocorticoid receptors (GR) are receptors to which cortisol (and other glucocorticoids) bind. The bound receptor is involved in the regulation of gene transcription. The GR gene promoter region has a sequence that allows for binding by the transcription factor nerve growth factor induced protein A (NGFI-A), which is involved in neuronal plasticity. In rats, it has been shown that individuals less susceptible to depressive behavior have increased binding of NGFI-A to the promoter region of the GR gene, specifically in the hippocampus. As a result, there is an increased amount of hippocampal GR expression, both in transcription of its mRNA and overall protein level.

This is associated with an increase in acetylation of H3K9 in the GR promoter region. Methylation of CpG islands in the promoter region of GR leads to a decrease in the ability of NGFI-A to bind to the GR promoter region. It has also been experimentally shown that methylation of CpG sites in the enhancer region bound by NGFI-A is detrimental to the ability of NGFI-A to bind to the promoter region. Furthermore, the methylation of the promoter region results in a decrease in recruitment of the CREB-binding protein, which has histone acetyltransferase ability. This results in less acetylation of the histones, which has been shown to be a modification that takes place within individuals less susceptible to depression.

Due to environmental factors, there is a decrease in methylation of the promoter region of the GR gene, which then allows for increased binding of the NGFI-A protein, and as a result, an increase in the expression of the GR gene. This results in decreased depressive behavior.

Treatment

Antidepressants

Through computational methodology, epigenetics has been found to play a critical role in mood disorder susceptibility and development, and has also been shown to mediate treatment response to SSRI medications. SSRI medications including fluoxetine, paroxetine, and escitalopram reduce gene expression and enzymatic activity related to methylation and acetylation pathways in numerous brain regions implicated in patients with major depression.

Pharmacogenetic research has focused on epigenetic factors related to BDNF, which has been a biomarker for neuropsychiatric diseases. BDNF has been shown to be sensitive to the prolonged effects of stress (a common risk factor of depressive phenotypes), with epigenetic modifications (primarily histone methylation) at BDNF promoters and splice variants. Such variation in gene splicing and repressed hippocampal BDNF expression is associated with major depressive disorder while increased expression in this region is associated with successful antidepressant treatment. Patients suffering from major depression and bipolar disorder show increased methylation at BDNF promoters and reduced BDNF mRNA levels in the brain and in blood monocytes while SSRI treatment in patients with depression results in decreased histone methylation and increased BDNF levels.

In addition to the BDNF gene, micro RNAs (miRNAs) play a role in mood disorders, and transcript levels are suggested in SSRI treatment efficacy. Post-mortem work in patients with major depressive disorder, as well as other psychiatric diseases, show that miRNAs play a critical role in regulating brain structure via synaptic plasticity and neurogenesis. Increased hippocampal neural development plays a role in the efficacy of antidepressant treatment, while reductions in such development is related to neuropsychiatric disorders. In particular, the miRNA MIR-16 plays a critical role in regulating these processes in individuals with mood disorders. Increased hippocampal MIR-16 inhibits proteins which promote neurogenesis including the serotonin transporter (SERT), which is the target of SSRI therapeutics. MIR-16 downregulates SERT expression in humans, which decreases the number of serotonin transporters. Inhibition of MIR-16 therefore promotes SERT production and serves as a target for SSRI therapeutics. SSRI medications increase neurogenesis in the hippocampus by reductions in MIR-16, thereby restoring hippocampal neuronal activity following treatment in patients suffering from neuropsychiatric disorders. In patients with major depressive disorder, treatment with SSRI medications results in differential expression of 30 miRNAs, half of which play a role in modulating neuronal structure and/or are implicated in psychiatric disorders.

Understanding epigenetic profiles of patients suffering from neuropsychiatric disorders in key brain regions has led to more knowledge of patient outcome following SSRI treatment. Genome wide association studies seek to assess individual polymorphisms in genes which are implicated in depressive phenotypes, and aid in the efficacy of pharmacogenetic studies. Single-nucleotide polymorphisms of the 5-HT(2A) gene correlated with paroxetine discontinuation due to side effects in a group of elderly patients with major depression, but not mirtazapine (a non-SSRI antidepressant) discontinuation. In addition, hypomethylation of the SERT promoter was correlated with poor patient outcomes and treatment success following 6 weeks of escitalopram treatment. Such work addressing methylation patterns in the periphery has been shown to be comparable to methylation patterns in brain tissue, and provides information allowing for tailored pharmacogenetic approaches.

BDNF as a serotonin modulator

Decreased brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) is known to be associated with depression. Research suggests that increasing BDNF can reverse some symptoms of depression. For instance, increased BDNF signaling can reverse the reduced hippocampal brain signaling observed in animal models of depression. BDNF is involved in depression through its effects on serotonin. BDNF has been shown to promote the development, function, and expression of serotonergic neurons. Because more active serotonin results in more positive moods, antidepressants work to increase serotonin levels. Tricyclic antidepressants generally work by blocking serotonin transporters in order to keep serotonin in the synaptic cleft where it is still active. Noradrenergic and specific serotonergic antidepressants antagonize serotonin receptors. Noradrenergic and specific serotonergic antidepressants (NaSSAs) such as miratzapine and tricyclic antidepressants such as imapramine both increased BDNF in the cerebral cortices and hippocampi of rats. Because BDNF mRNA levels increase with long-term miratzapine use, increasing BDNF gene expression may be necessary for improvements in depressive behaviors. This also increases the potential for neuronal plasticity. Generally, these antidepressants increase peripheral BDNF levels by reducing methylation at BDNF promoters that are known to modulate serotonin. As BDNF expression is increased when H3K27me3 is decreased with antidepressant treatment, BDNF increases its effect on serotonin modulation. It modulates serotonin by downregulating the G protein-coupled receptor, 5-HT2A receptor protein levels in the hippocampus. This increased BDNF increases the inhibition of presynaptic serotonin uptake, which results in fewer symptoms of depression.

Effects of antidepressants on glucocorticoid receptors

Increased NGFI-A binding, and the resulting increase in glucocorticoid receptor (GR) expression, leads to a decrease in depression-like behavior. Antidepressants can work to increase GR levels in affected patients, suppressing depressive symptoms. Electric shock therapy, is often used to treat patients suffering from depression. It is found that this form of treatment results in an increase in NGFI-A expression levels. Electric shock therapy depolarizes a number of neurons throughout the brain, resulting in the increased activity of a number of intracellular pathways. This includes the cAMP pathway which, through downstream effects, results in expression of NGFI-A. Antidepressant drugs, such as Tranylcypromine and Imipramine were found to have a similar effect; treatment with these drugs led to increases in NGFI-A expression and subsequent GR expression. These two drugs are thought to alter synaptic levels of 5-HT, which then alters the activity level of the cAMP pathway. It is also known that increased glucocorticoid receptor expression has been shown to modulate the HPA pathway by increasing negative feedback. This increase in expression results from decreased methylation, increased acetylation and binding of HGFI-A transcription factor. This promotes a more moderate HPA response than seen in those with depression which then decreases levels of hormones associated with stress. Another antidepressant, Desipramine was found to increase GR density and GR mRNA expression in the hippocampus. It is thought that this is happening due to an interaction between the response element of GR and the acetyltransferase, CREB Binding Protein. Therefore, this antidepressant, by increasing acetylation, works to lessen the HPA response, and as a result, decrease depressive symptoms.

HDAC inhibitors as antidepressants

HDAC inhibitors have been show to cause antidepressant-like effects in animals. Research shows that antidepressants make epigenetic changes to gene transcription thus altering signaling. These gene expression changes are seen in the BDNF, CRF, GDNF, and GR genes (see above sections). Histone modifications are consistently reported to alter chromatin structure during depression by the removal of acetyl groups, and to reverse this, HDAC inhibitors work by countering the removal of acetyl groups on histones. HDAC inhibitors can decrease gene transcription in the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex that is increased as a characteristic of depression. In animal studies of depression, short-term administration of HDAC inhibitors reduced the fear response in mice, and chronic administration produced antidepressant-like effects. This suggests that long-term treatment of HDAC inhibitors help in the treatment of depression. Some studies show that administration of HDAC inhibitors like Vorinostat and Romidepsin, hematologic cancer drugs, can augment the effect of other antidepressants. These HDAC inhibitors may become antidepressants in the future, but clinical trials must further assess their efficacy in humans.