A tariff is a tax imposed by the government of a country or by a supranational union on imports or exports of goods. Besides being a source of revenue for the government, import duties can also be a form of regulation of foreign trade and policy that taxes foreign products to encourage or safeguard domestic industry. Protective tariffs are among the most widely used instruments of protectionism, along with import quotas and export quotas and other non-tariff barriers to trade.

Tariffs can be fixed (a constant sum per unit of imported goods or a percentage of the price) or variable (the amount varies according to the price). Tariffs on imports are designed to raise the price of imported goods and services to discourage consumption. The intention is for citizens to buy local products instead, thereby stimulating their country's economy. Tariffs therefore provide an incentive to develop production and replace imports with domestic products. Tariffs are meant to reduce pressure from foreign competition and reduce the trade deficit. They have historically been justified as a means to protect infant industries and to allow import substitution industrialisation (industrializing a nation by replacing imported goods with domestic production). Tariffs may also be used to rectify artificially low prices for certain imported goods, due to 'dumping', export subsidies or currency manipulation.

There is near unanimous consensus among economists that tariffs are self-defeating and have a negative effect on economic growth and economic welfare, while free trade and the reduction of trade barriers has a positive effect on economic growth. Although trade liberalisation can sometimes result in large and unequally distributed losses and gains, and can, in the short run, cause significant economic dislocation of workers in import-competing sectors, free trade has advantages of lowering costs of goods and services for both producers and consumers. The economic burden of tariffs falls on the importer, the exporter, and the consumer. Often intended to protect specific industries, tariffs can end up backfiring and harming the industries they were intended to protect through rising input costs and retaliatory tariffs. Import tariffs can also harm domestic exporters by disrupting their supply chains and raising their input costs.

Etymology

The English term tariff derives from the French: tarif, lit. 'set price' which is itself a descendant of the Italian: tariffa, lit. 'mandated price; schedule of taxes and customs' which derives from Medieval Latin: tariffe, lit. 'set price'. This term was introduced to the Latin-speaking world through contact with the Turks and derives from the Ottoman Turkish: تعرفه, romanized: taʿrife, lit. 'list of prices; table of the rates of customs'. This Turkish term is a loanword of the Persian: تعرفه, romanized: taʿrefe, lit. 'set price, receipt'. The Persian term derives from Arabic: تعريف, romanized: taʿrīf, lit. 'notification; description; definition; announcement; assertion; inventory of fees to be paid' which is the verbal noun of Arabic: عرف, romanized: ʿarafa, lit. 'to know; to be able; to recognise; to find out'.

History

Ancient Greece

In the city state of Athens, the port of Piraeus enforced a system of levies to raise taxes for the Athenian government. Grain was a key commodity that was imported through the port, and Piraeus was one of the main ports in the east Mediterranean. A levy of two percent was placed on goods arriving in the market through the docks of Piraeus. The Athenian government also placed restrictions on the lending of money and transport of grain to only be allowed through the port of Piraeus.

Great Britain

In the 14th century, Edward III took interventionist measures, such as banning the import of woollen cloth in an attempt to develop local manufacturing. Beginning in 1489, Henry VII took actions such as increasing export duties on raw wool. The Tudor monarchs, especially Henry VIII and Elizabeth I, used protectionism, subsidies, distribution of monopoly rights, government-sponsored industrial espionage and other means of government intervention to develop the wool industry, leading to England became the largest wool-producing nation in the world.

A protectionist turning point in British economic policy came in 1721, when policies to promote manufacturing industries were introduced by Robert Walpole. These included, for example, increased tariffs on imported foreign manufactured goods, export subsidies, reduced tariffs on imported raw materials used for manufactured goods and the abolition of export duties on most manufactured goods. Thus, the UK was the first country to pursue a strategy of large-scale infant-industry development. These policies were similar to those used by countries such as Japan, Korea and Taiwan after the Second World War. Outlining his policy, Walpole declared:

Nothing contributes as much to the promotion of public welfare as the export of manufactured goods and the import of foreign raw materials.

Walpole's protectionist policies continued over the next century, helping British manufacturing catch up with and then leapfrog its continental counterparts. Britain remained a highly protectionist country until the mid-19th century. By 1820, the UK's average tariff rate on manufactured imports was 45-55%. Moreover, in its colonies, the UK imposed a total ban on advanced manufacturing activities that the country did not want to see developed. Walpole forced Americans to specialize in low-value-added products. The UK also banned exports from its colonies that competed with its own products at home and abroad. The country banned imports of cotton textiles from India, which at the time were superior to British products. It banned the export of woollen fabrics from its colonies to other countries (Wool Act). Finally, Britain wanted to ensure that the colonists stuck to the production of raw materials and never became a competitor to British manufacturers. Policies were established to encourage the production of raw materials in the colonies. Walpole granted export subsidies (on the American side) and abolished import taxes (on the British side) on raw materials produced in the American colonies. The colonies were thus forced to leave the most profitable industries in the hands of the United Kingdom.

In 1800, Britain, with about 10% of Europe's population, supplied 29% of all pig iron produced in Europe, a proportion that had risen to 45% by 1830. Per capita industrial production was even higher: in 1830 it was 250% higher than in the rest of Europe, up from 110% in 1800.

Protectionist policies of industrial promotion continued until the mid-19th century. At the beginning of that century, the average tariff on British manufactured goods was about 50%, the highest of all major European countries. Despite its growing technological lead over other nations, the UK continued its policy of industrial promotion until the mid-19th century, maintaining very high tariffs on manufactured goods until the 1820s, two generations after the start of the Industrial Revolution. Thus, according to economic historian Paul Bairoch, the UK's technological advance was achieved "behind high and durable tariff barriers". In 1846, the rate of industrialization per capita was more than double that of its closest competitors. Even after adopting free trade for most goods, Britain continued to closely regulate trade in strategic capital goods, such as machinery for the mass production of textiles.

Free trade in Britain began in earnest with the repeal of the Corn Laws in 1846, which was equivalent to free trade in grain. The Corn Acts had been passed in 1815 to restrict wheat imports and to guarantee the incomes of British farmers; their repeal devastated Britain's old rural economy, but began to mitigate the effects of the Great Famine in Ireland. Tariffs on many manufactured goods were also abolished. But while free-trade was progressing in Britain, protectionism continued on the European mainland and in the United States.

Customs duties on many manufactured goods were also abolished. The Navigation Acts were abolished in 1849 when free traders won the public debate in the UK. But while free trade progressed in the UK, protectionism continued on the Continent. The UK practiced free trade unilaterally in the vain hope that other countries would follow, but the USA emerged from the Civil War even more explicitly protectionist than before, Germany under Bismarck rejected free trade, and the rest of Europe followed suit.

After the 1870s, the British economy continued to grow, but inexorably lagged behind the protectionist United States and Germany: from 1870 to 1913, industrial production grew at an average annual rate of 4.7% in the USA, 4.1% in Germany and only 2.1% in Great Britain. Thus, Britain was finally overtaken economically by the United States around 1880. British leadership in fields such as steel and textiles was eroded, and the country fell behind as new, more technologically advanced industries emerged after 1870 in other countries still practicing protectionism.

On June 15, 1903, the Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs, Henry Petty-Fitzmaurice, 5th Marquess of Lansdowne, made a speech in the House of Lords in which he defended fiscal retaliation against countries that applied high tariffs and whose governments subsidised products sold in Britain (known as "premium products", later called "dumping"). The retaliation was to take the form of threats to impose duties in response to goods from that country. Liberal unionists had split from the liberals, who advocated free trade, and this speech marked a turning point in the group's slide toward protectionism. Lansdowne argued that the threat of retaliatory tariffs was similar to gaining respect in a room of gunmen by pointing a big gun (his exact words were "a gun a little bigger than everyone else's"). The "Big Revolver" became a slogan of the time, often used in speeches and cartoons.

In response to the Great Depression, Britain abandoned free trade in 1932, recognizing that it had lost production capacity to the United States and Germany, which remained protectionist. The country reintroduced large-scale tariffs, but it was too late to re-establish the nation's position as a dominant economic power. In 1932, the level of industrialization in the United States was 50% higher than in the United Kingdom.

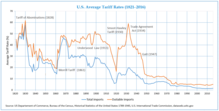

United States

Before the new Constitution took effect in 1788, the Congress could not levy taxes – it sold land or begged money from the states. The new national government needed revenue and decided to depend upon a tax on imports with the Tariff of 1789. The policy of the U.S. before 1860 was low tariffs "for revenue only" (since duties continued to fund the national government).

The Embargo Act of 1807 was passed by the U.S. Congress in that year in response to British aggression. While not a tariff per se, the Act prohibited the import of all kinds of manufactured imports, resulting in a huge drop in US trade and protests from all regions of the country. However, the embargo also had the effect of launching new, emerging US domestic industries across the board, particularly the textile industry, and marked the beginning of the manufacturing system in the United States.

An attempt at imposing a high tariff occurred in 1828, but the South denounced it as a "Tariff of Abominations" and it almost caused a rebellion in South Carolina until it was lowered.

Between 1816 and the end of the Second World War, the United States had one of the highest average tariff rates on manufactured imports in the world. According to Paul Bairoch, the United States was "the homeland and bastion of modern protectionism" during this period.

Many American intellectuals and politicians during the country's catching-up period felt that the free trade theory advocated by British classical economists was not suited to their country. They argued that the country should develop manufacturing industries and use government protection and subsidies for this purpose, as Britain had done before them. Many of the great American economists of the time, until the last quarter of the 19th century, were strong advocates of industrial protection: Daniel Raymond who influenced Friedrich List, Mathew Carey and his son Henry, who was one of Lincoln's economic advisers. The intellectual leader of this movement was Alexander Hamilton, the first Secretary of the Treasury of the United States (1789–1795). The United States rejected David Ricardo's theory of comparative advantage and protected its industry. The country pursued a protectionist policy from the beginning of the 19th century until the middle of the 20th century, after the Second World War.

In Report on Manufactures, considered the first text to express modern protectionist theory, Alexander Hamilton argued that if a country wished to develop a new activity on its soil, it would have to temporarily protect it. According to him, this protection against foreign producers could take the form of import duties or, in rare cases, prohibition of imports. He called for customs barriers to allow American industrial development and to help protect infant industries, including bounties (subsidies) derived in part from those tariffs. He also believed that duties on raw materials should be generally low. Hamilton argued that despite an initial "increase of price" caused by regulations that control foreign competition, once a "domestic manufacture has attained to perfection... it invariably becomes cheaper. In this report, Hamilton also proposed export bans on major raw materials, tariff reductions on industrial inputs, pricing and patenting of inventions, regulation of product standards and development of financial and transportation infrastructure. The U.S. Congress adopted the tariffs but refused to grant subsidies to manufactures. Hamilton's arguments shaped the pattern of American economic policy until the end of World War II, and his program created the conditions for rapid industrial development.

Alexander Hamilton and Daniel Raymond were among the first theorists to present the infant industry argument. Hamilton was the first to use the term "infant industries" and to introduce it to the forefront of economic thinking. Hamilton believed that political independence was predicated upon economic independence. Increasing the domestic supply of manufactured goods, particularly war materials, was seen as an issue of national security. And he feared that Britain's policy towards the colonies would condemn the United States to be only producers of agricultural products and raw materials.

Britain initially did not want to industrialise the American colonies, and implemented policies to that effect (for example, banning high value-added manufacturing activities). Under British rule, America was denied the use of tariffs to protect its new industries. This explains why, after independence, the Tariff Act of 1789 was the second bill of the Republic signed by President Washington allowing Congress to impose a fixed tariff of 5% on all imports, with a few exceptions.

The Congress passed a tariff act (1789), imposing a 5% flat rate tariff on all imports. Between 1792 and the war with Britain in 1812, the average tariff level remained around 12.5%, which was too low to encourage consumers to buy domestic products and thus support emerging American industries. When the Anglo-American War of 1812 broke out, all rates doubled to an average of 25% to account for increased government spending. The war paved the way for new industries by disrupting manufacturing imports from the UK and the rest of Europe. A major policy shift occurred in 1816, when American manufacturers who had benefited from the tariffs lobbied to retain them. New legislation was introduced to keep tariffs at the same levels —especially protected were cotton, woolen, and iron goods. The American industrial interests that had blossomed because of the tariff lobbied to keep it, and had it raised to 35 percent in 1816. The public approved, and by 1820, America's average tariff was up to 40 percent.

In the 19th century, statesmen such as Senator Henry Clay continued Hamilton's themes within the Whig Party under the name "American System" which consisted of protecting industries and developing infrastructure in explicit opposition to the "British system" of free trade. Before 1860 they were always defeated by the low-tariff Democrats.

From 1846 to 1861, American tariffs were lowered but this was followed by a series of recessions and the 1857 panic, which eventually led to higher demands for tariffs than President James Buchanan signed in 1861 (Morrill Tariff).

During the American Civil War (1861–1865), agrarian interests in the South were opposed to any protection, while manufacturing interests in the North wanted to maintain it. The war marked the triumph of the protectionists of the industrial states of the North over the free traders of the South. Abraham Lincoln was a protectionist like Henry Clay of the Whig Party, who advocated the "American system" based on infrastructure development and protectionism. In 1847, he declared: "Give us a protective tariff, and we will have the greatest nation on earth". Once elected, Lincoln implemented a 44-percent tariff during the Civil War—in part to pay for railroad subsidies and for the war effort, and to protect favored industries. After the war, tariffs remained at or above wartime levels. High tariffs were a policy designed to encourage rapid industrialisation and protect the high American wage rates.[31]

The policy from 1860 to 1933 was usually high protective tariffs (apart from 1913 to 1921). After 1890, the tariff on wool did affect an important industry, but otherwise the tariffs were designed to keep American wages high. The conservative Republican tradition, typified by William McKinley was a high tariff, while the Democrats typically called for a lower tariff to help consumers but they always failed until 1913.[35][36]

In the early 1860s, Europe and the United States pursued completely different trade policies. The 1860s were a period of growing protectionism in the United States, while the European free trade phase lasted from 1860 to 1892. The tariff average rate on imports of manufactured goods in 1875 was from 40% to 50% in the United States, against 9% to 12% in continental Europe at the height of free trade.

From 1871 to 1913, "the average U.S. tariff on dutiable imports never fell below 38 percent [and] gross national product (GNP) grew 4.3 percent annually, twice the pace in free trade Britain and well above the U.S. average in the 20th century," notes Alfred Eckes Jr, chairman of the U.S. International Trade Commission under President Reagan.

After the United States caught up with European industries in the 1890s, the Mckinley Tariff's argument was no longer to protect "infant industries", but to maintain workers' wages, support agricultural protection and the principle of reciprocity.

In 1896, the Republican Party platform pledged to "renew and emphasize our allegiance to the policy of protection, as the bulwark of American industrial independence, and the foundation of development and prosperity. This true American policy taxes foreign products and encourages home industry. It puts the burden of revenue on foreign goods; it secures the American market for the American producer. It upholds the American standard of wages for the American workingman".

In 1913, following the electoral victory of the Democrats in 1912, there was a significant reduction in the average tariff on manufactured goods from 44% to 25%. However, the First World War rendered this bill ineffective, and new "emergency" tariff legislation was introduced in 1922 after the Republicans returned to power in 1921.

According to economic historian Douglas Irwin, a common myth about United States trade policy is that low tariffs harmed American manufacturers in the early 19th century and then that high tariffs made the United States into a great industrial power in the late 19th century. A review by the Economist of Irwin's 2017 book Clashing over Commerce: A History of US Trade Policy notes:

Political dynamics would lead people to see a link between tariffs and the economic cycle that was not there. A boom would generate enough revenue for tariffs to fall, and when the bust came pressure would build to raise them again. By the time that happened, the economy would be recovering, giving the impression that tariff cuts caused the crash and the reverse generated the recovery. Mr Irwin also methodically debunks the idea that protectionism made America a great industrial power, a notion believed by some to offer lessons for developing countries today. As its share of global manufacturing powered from 23% in 1870 to 36% in 1913, the admittedly high tariffs of the time came with a cost, estimated at around 0.5% of GDP in the mid-1870s. In some industries, they might have sped up development by a few years. But American growth during its protectionist period was more to do with its abundant resources and openness to people and ideas.

The Economist Ha-Joon Chang argues, on the contrary, that the United States developed and rose to the top of the global economic hierarchy by adopting protectionism. In his view, the protectionist period corresponded to the golden age of American industry, when US economic performance outstripped that of the rest of the world. The U.S. adopted an interventionist policy to promote and protect their industries through tariffs. It was this protectionist policy that enabled the United States to achieve the fastest economic growth in the world throughout the 19th century and into the 1920s.

Tariffs and the Great Depression

Paul Krugman writes that protectionism does not lead to recessions. According to him, the decrease in imports (which can be obtained by introducing tariffs) has an expansive effect, that is, it is favourable to growth. Thus, in a trade war, since exports and imports will decrease equally, for everyone, the negative effect of a decrease in exports will be offset by the expansionary effect of a decrease in imports. Therefore, a trade war does not cause a recession. Furthermore, in his view, the Smoot-Hawley tariff did not cause the Great Depression and that the decline in trade between 1929 and 1933 "was almost entirely a consequence of the Depression, not a cause. Trade barriers were a response to the Depression".

According to the historian Paul Bairoch, the years 1920 to 1929 are generally misdescribed as years in which protectionism increased in Europe. Instead, he says that from a general point of view, the crisis was preceded in Europe by trade liberalisation. The weighted average of tariffs remained tendentially the same as in the years preceding the First World War: 24.6% in 1913, as against 24.9% in 1927. In 1928 and 1929, tariffs were lowered in almost all developed countries.

Douglas A. Irwin says most economists "doubt that Smoot–Hawley played much of a role in the subsequent contraction."

Nevertheless, The Economist observes that "... global trade fell by two-thirds. It was so catastrophic for growth in America and around the world that legislators have not touched the issue since. 'Smoot-Hawley' became synonymous with disastrous policy making".

Economist Milton Friedman argued that while the tariffs of 1930 caused harm, they were not responsible by themselves for the Great Depression. He placed greater blame on the lack of sufficient action on the part of the Federal Reserve. Peter Temin, an economist at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, has agreed that the contractionary effect of the tariff was small.

According to William J. Bernstein, most economic historians now believe that only a fraction of the GDP loss worldwide and in the U.S. resulted from tariff wars. Bernstein argued that the decline "could not have exceeded 1 or 2% of world GDP, a far cry from the 17% recorded during the Great Depression."

Jacques Sapir argued that the crisis has other causes than protectionism. He points out that "domestic production in major industrialized countries is declining...faster than international trade is declining." If this decrease (in international trade) had been the cause of the depression that the countries have experienced, we would have seen the opposite". "Finally, the chronology of events does not correspond to the thesis of the free traders... The bulk of the contraction of trade occurred between January 1930 and July 1932, that is, before the introduction of protectionist measures, even self-sufficient, in some countries, with the exception of those applied in the United States in the summer of 1930, but with very limited negative effects. He noted that "the credit crunch is one of the main causes of the trade crunch." "In fact, international liquidity is the cause of the trade contraction. This liquidity collapsed in 1930 (-35.7%) and 1931 (-26.7%). A study by the National Bureau of Economic Research highlights the predominant influence of currency instability (which led to the international liquidity crisis) and the sudden rise in transportation costs in the decline of trade during the 1930s.

Other economists have contended that the record tariffs of the 1920s and early 1930s exacerbated the Great Depression in the U.S., in part because of retaliatory tariffs imposed by other countries on the United States.

Arguments favouring tariffs

Protection against dumping

States resorting to protectionism invoke unfair competition or dumping practices:

- Monetary manipulation: a currency undergoes a devaluation when monetary authorities decide to intervene in the foreign exchange market to lower the value of the currency against other currencies. This makes local products more competitive and imported products more expensive (Marshall Lerner Condition), increasing exports and decreasing imports, and thus improving the trade balance. Countries with a weak currency cause trade imbalances: they have large external surpluses while their competitors have large deficits. For example, in 2010, Paul Krugman wrote that China pursues a mercantilist and predatory policy, i.e., it keeps its currency undervalued to accumulate trade surpluses by using capital flow controls. The Chinese government sells renminbi and buys foreign currency to keep the renminbi low, giving the Chinese manufacturing sector a cost advantage over its competitors. China's surpluses drain US demand and slow economic recovery in other countries with which China trades. Krugman writes: "This is the most distorted exchange rate policy any great nation has ever followed". He notes that an undervalued renminbi is tantamount to imposing high tariffs or providing export subsidies. A cheaper currency improves employment and competitiveness because it makes imports more expensive while making domestic products more attractive.

- Tax dumping: some tax haven states have lower corporate and personal tax rates.

- Social dumping: when a state reduces social contributions or maintains very low social standards. For example, in several U.S. states labor regulations are considerably lax and the laws that do exist are barely enforced (if at all). Thus employers can force vulnerable, migrant children into factory work for a fraction of the cost of legal adult labor. These children are often injured or killed.

- Environmental dumping: when environmental regulations are less stringent than elsewhere. For example, the European Union starts its carbon border-adjustment mechanism in 2026 to even the playing field with firms not subject to European carbon pricing.

Protection of infant industry

According to the economists in favour of protecting industries, free trade would condemn developing countries to being nothing more than exporters of raw materials and importers of manufactured goods. The application of the theory of comparative advantage would lead them to specialise in the production of raw materials and extractive products and prevent them from acquiring an industrial base. Protection of infant industries (e.g., through tariffs on imported products) may be needed for some developing countries to industrialise and escape their dependence on the production of raw materials.

Economist Ha-Joon Chang argued in 2001 that most of today's developed countries have developed through policies that are the opposite of free trade and laissez-faire such as interventionist trade and industrial policies to promote and protect infant industries. In his view, Britain and the United States have not reached the top of the global economic hierarchy by adopting free trade. As for the East Asian countries, he argues that the longest periods of rapid growth in these countries do not coincide with extended phases of free trade, but rather with phases of industrial protection and promotion. He believes infant industry protection policy has generated much better growth performance in the developing world than free trade policies since the 1980s.

In the second half of the 20th century, Nicholas Kaldor takes up similar arguments to allow the conversion of ageing industries. In this case, the aim was to save an activity threatened with extinction by external competition and to safeguard jobs. Protectionism must enable ageing companies to regain their competitiveness in the medium term and, for activities that are due to disappear, it allows the conversion of these activities and jobs.

Free trade and poverty

In an op-ed article for The Guardian (UK), Ha-Joon Chang argues that economic downturns in Africa are the result of free trade policies, and elsewhere attributes successes in some African countries such as Ethiopia and Rwanda to their abandonment of free trade and adoption of a "developmental state model".

Some commentators argue that poor countries and regions that have succeeded in achieving strong and sustainable growth are those that have become mercantilists, not free traders: China, South Korea, Japan, Taiwan.

The 'dumping' policies of some countries have also largely affected developing countries. Studies on the effects of free trade show that the gains induced by WTO rules for developing countries are very small. This has reduced the gain for these countries from an estimated $539 billion in the 2003 LINKAGE model to $22 billion in the 2005 GTAP model. The 2005 LINKAGE version also reduced gains to 90 billion. As for the "Doha Round", it would have brought in only $4 billion to developing countries (including China...) according to the GTAP model. However, it has been argued that the models used are actually designed to maximise the positive effects of trade liberalisation, that they are characterised by the absence of taking into account the loss of income caused by the end of tariff barriers.

Trade deficits

The notion that bilateral trade deficits are per se detrimental to the respective national economies is overwhelmingly rejected by trade experts and economists.

Arguments against tariffs

Neoclassical analysis in favor of free trade

Neoclassical economic theorists tend to view tariffs as distortions to the free market. Typical analyses find that tariffs tend to benefit domestic producers and government at the expense of consumers, and that the net welfare effects of a tariff on the importing country are negative due to domestic firms not producing more efficiently since there is a lack of external competition. Therefore, domestic consumers are affected since the price is higher due to high costs caused due to inefficient production or if firms are not able to source cheaper material externally thus reducing the affordability of the products. Normative judgments often follow from these findings, namely that it may be disadvantageous for a country to artificially shield an industry from world markets and that it might be better to allow a collapse to take place. Opposition to all tariff aims to reduce tariffs and to avoid countries discriminating between differing countries when applying tariffs. The diagrams at right show the costs and benefits of imposing a tariff on a good in the domestic economy.

Imposing an import tariff has the following effects, shown in the first diagram in a hypothetical domestic market for televisions:

- Price rises from world price Pw to higher tariff price Pt.

- Quantity demanded by domestic consumers falls from C1 to C2, a movement along the demand curve due to higher price.

- Domestic suppliers are willing to supply Q2 rather than Q1, a movement along the supply curve due to the higher price, so the quantity imported falls from C1−Q1 to C2−Q2.

- Consumer surplus (the area under the demand curve but above price) shrinks by areas A+B+C+D, as domestic consumers face higher prices and consume lower quantities.

- Producer surplus (the area above the supply curve but below price) increases by area A, as domestic producers shielded from international competition can sell more of their product at a higher price.

- Government tax revenue is the import quantity (C2 − Q2) times the tariff price (Pw − Pt), shown as area C.

- Areas B and D are deadweight losses, surplus formerly captured by consumers that now is lost to all parties.

The overall change in welfare = Change in Consumer Surplus + Change in Producer Surplus + Change in Government Revenue = (−A−B−C−D) + A + C = −B−D. The final state after imposition of the tariff is indicated in the second diagram, with overall welfare reduced by the areas labeled "societal losses", which correspond to areas B and D in the first diagram. The losses to domestic consumers are greater than the combined benefits to domestic producers and government.

That tariffs overall reduce welfare is not a controversial topic among economists. For example, the University of Chicago surveyed about 40 leading economists in March 2018 asking whether "Imposing new U.S. tariffs on steel and aluminum will improve Americans' welfare." About two-thirds strongly disagreed with the statement, while one third disagreed. None agreed or strongly agreed. Several commented that such tariffs would help a few Americans at the expense of many. This is consistent with the explanation provided above, which is that losses to domestic consumers outweigh gains to domestic producers and government, by the amount of deadweight losses.

Tariffs are more inefficient than consumption taxes.

A 2021 study found that across 151 countries over the period 1963–2014, "tariff increases are associated with persistent, economically and statistically significant declines in domestic output and productivity, as well as higher unemployment and inequality, real exchange rate appreciation, and insignificant changes to the trade balance."

Tariffs do not determine the size of trade deficits: trade balances are driven by consumption. Rather, it is that a strong economy creates rich consumers who in turn create the demand for imports. Industries protected by tariffs expand their domestic market share but an additional effect is that their need to be efficient and cost-effective is reduced. This cost is imposed on (domestic) purchasers of the products of those industries, a cost that is eventually passed on to the end consumer. Finally, other countries must be expected to retaliate by imposing countervailing tariffs, a lose-lose situation that would lead to increased world-wide inflation.

Optimal tariff

For economic efficiency, free trade is often the best policy, however levying a tariff is sometimes second best.

A tariff is called an optimal tariff if it is set to maximise the welfare of the country imposing the tariff. It is a tariff derived by the intersection between the trade indifference curve of that country and the offer curve of another country. In this case, the welfare of the other country grows worse simultaneously, thus the policy is a kind of beggar thy neighbor policy. If the offer curve of the other country is a line through the origin point, the original country is in the condition of a small country, so any tariff worsens the welfare of the original country.

It is possible to levy a tariff as a political policy choice, and to consider a theoretical optimum tariff rate. However, imposing an optimal tariff will often lead to the foreign country increasing their tariffs as well, leading to a loss of welfare in both countries. When countries impose tariffs on each other, they will reach a position off the contract curve, meaning that both countries' welfare could be increased by reducing tariffs.

Modern tariff practices

Russia

The Russian Federation adopted more protectionist trade measures in 2013 than any other country, making it the world leader in protectionism. It alone introduced 20% of protectionist measures worldwide and one-third of measures in the G20 countries. Russia's protectionist policies include tariff measures, import restrictions, sanitary measures, and direct subsidies to local companies. For example, the government supported several economic sectors such as agriculture, space, automotive, electronics, chemistry, and energy.

India

From 2017, as part of the promotion of its "Make in India" programme to stimulate and protect domestic manufacturing industry and to combat current account deficits, India has introduced tariffs on several electronic products and "non-essential items". This concerns items imported from countries such as China and South Korea. For example, India's national solar energy programme favours domestic producers by requiring the use of Indian-made solar cells.

Armenia

Armenia, a country located in Western Asia, established its custom service in 1992 after the dissolution of the Soviet Union. When Armenia became a member of the EAEU, it was given access to the Eurasian Customs Union in 2015; this resulted in mostly tariff-free trade with other members and an increased number of import tariffs from outside of the customs union. Armenia does not currently have export taxes. In addition, it does not declare temporary imports duties and credit on government imports or pursuant to other international assistance imports. Upon joining Eurasian Economic Union in 2015, led by Russians, Armenia applied tariffs on its imports at a rate 0–10 percent. This rate has increased over the years, since in 2009 it was around three percent. Moreover, the tariffs increased significantly on agricultural products rather than on non-agricultural products. Armenia has committed to ultimately adopting the EAEU's uniform tariff schedule as part of its EAEU admission. Until 2022, Armenia was authorised to apply non-EAEU tariff rates, according to Decision No. 113. Some beef, pork, poultry, and dairy products; seed potatoes and peas; olives; fresh and dried fruits; some tea items; cereals, especially wheat and rice; starches, vegetable oils, margarine; some prepared food items, such as infant food; pet food; tobacco; glycerol; and gelatin are included in the list. Membership in the EAEU is forcing Armenia to apply stricter standardisation, sanitary, and phytosanitary requirements in line with EAEU – and, by extension, Russian – standards, regulations, and practices. Armenia has had to surrender control over many aspects of its foreign trade regime in the context of EAEU membership. Tariffs have also increased, granting protection to several domestic industries. Armenia is increasingly beholden to comply with EAEU standards and regulations as post-accession transition periods have, or will soon, end. All Armenian goods circulating in the territory of the EAEU must meet EAEU requirements following the end of relevant transition periods.

Armenia became a WTO member in 2003, which resulted in the Most Favored Country (MFC) benefits from the organisation. Currently, the tariffs of 2.7% implemented in Armenia are the lowest in the entire framework. The country is also a member of the World Customs Organization (WCO), resulting in a harmonised system for tariff classification.

Switzerland

In 2024, Switzerland abolished tariffs on industrial products imported into the country. The Swiss government estimates the move will have economic benefits of 860 million CHF per year.

Political analysis

The tariff has been used as a political tool to establish an independent nation; for example, the United States Tariff Act of 1789, signed specifically on July 4, was called the "Second Declaration of Independence" by newspapers because it was intended to be the economic means to achieve the political goal of a sovereign and independent United States.

The political impact of tariffs is judged depending on the political perspective; for example, the 2002 United States steel tariff imposed a 30% tariff on a variety of imported steel products for a period of three years and American steel producers supported the tariff.

Tariffs can emerge as a political issue prior to an election. The Nullification Crisis of 1832 arose from the passage of a new tariff by the United States Congress, a few months before that year's federal elections; the state of South Carolina was outraged by the new tariff, and civil war nearly resulted. In the leadup to the 2007 Australian Federal election, the Australian Labor Party announced it would undertake a review of Australian car tariffs if elected. The Liberal Party made a similar commitment, while independent candidate Nick Xenophon announced his intention to introduce tariff-based legislation as "a matter of urgency".

Unpopular tariffs are known to have ignited social unrest, for example the 1905 meat riots in Chile that developed in protest against tariffs applied to the cattle imports from Argentina.

Additional information on tariffs

Calculation of customs duty

Customs duty is calculated on the determination of the 'assess-able value' in case of those items for which the duty is levied ad valorem. This is often the transaction value unless a customs officer determines assess-able value in accordance with the Harmonized System.

Harmonized System of Nomenclature

For the purpose of assessment of customs duty, products are given an identification code that has come to be known as the Harmonized System code. This code was developed by the World Customs Organization based in Brussels. A 'Harmonized System' code may be from four to ten digits. For example, 17.03 is the HS code for molasses from the extraction or refining of sugar. However, within 17.03, the number 17.03.90 stands for "Molasses (Excluding Cane Molasses)".

Customs authority

The national customs authority in each country is responsible for collecting taxes on the import into or export of goods out of the country.

Evasion

Evasion of customs duties takes place mainly in two ways. In one, the trader under-declares the value so that the assessable value is lower than actual. In a similar vein, a trader can evade customs duty by understatement of quantity or volume of the product of trade. A trader may also evade duty by misrepresenting traded goods, categorizing goods as items which attract lower customs duties. The evasion of customs duty may take place with or without the collaboration of customs officials.

Duty-free goods

Many countries allow a traveller to bring goods into the country duty-free. These goods may be bought at ports and airports or sometimes within one country without attracting the usual government taxes and then brought into another country duty-free. Some countries specify 'duty-free allowances' which limit the number or value of duty-free items that one person can bring into the country. These restrictions often apply to tobacco, wine, spirits, cosmetics, gifts and souvenirs.