From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

The

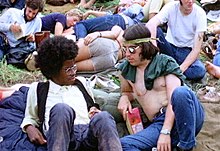

Summer of Love was a social phenomenon that occurred during mid-1967, when as many as 100,000 people, mostly young people sporting

hippie fashions of dress and behavior, converged in

San Francisco's neighborhood of

Haight-Ashbury.

More broadly, the Summer of Love encompassed the hippie music, drug,

anti-war, and free-love scene throughout the American west coast, and as

far away as New York City.

Hippies, sometimes called flower children, were an eclectic group. Many were

suspicious of the government,

rejected consumerist values, and generally

opposed the Vietnam War.

A few were interested in politics; others were concerned more with art

(music, painting, poetry in particular) or spiritual and meditative

practices.

Background

Culture of San Francisco

Junction of Haight and Ashbury Streets, San Francisco, celebrated as the central location of the Summer of Love

Inspired by the

Beat Generation of authors of the 1950s, who had flourished in the

North Beach

area of San Francisco, those who gathered in Haight-Ashbury during 1967

allegedly rejected the conformist and materialist values of modern

life; there was an emphasis on sharing and community. The

Diggers established a Free Store, and a

Free Clinic where medical treatment was provided.

Human Be-In and inspiration

It was at this event that

Timothy Leary voiced his phrase, "

turn on, tune in, drop out".

This phrase helped shape the entire hippie counterculture, as it voiced

the key ideas of 1960s rebellion. These ideas included communal living,

political decentralization, and dropping out. The term "dropping out"

became popular among many high school and college students, many of whom

would abandon their conventional education for a summer of hippie

culture.

A new concept of celebrations beneath the human

underground must emerge, become conscious, and be shared, so a

revolution can be formed with a renaissance of compassion, awareness,

and love, and the revelation of unity for all mankind.

The gathering of approximately 30,000 at the Human Be-In helped publicize hippie fashions.

Planning

The

term "Summer of Love" originated with the formation of the Council for

the Summer of Love during the spring of 1967 as a response to the

convergence of young people on the Haight-Ashbury district. The Council

was composed of

The Family Dog, The Straight Theatre, The Diggers,

The San Francisco Oracle,

and approximately twenty-five other people, who sought to alleviate

some of the problems anticipated from the influx of people expected

during the summer. The Council also assisted the Free Clinic and

organized housing, food, sanitation, music and arts, along with

maintaining coordination with local churches and other social groups.

Beginning

An anti-Vietnam War march in San Francisco on April 15, 1967

Youth arrivals

The

increasing numbers of youth traveling to the Haight-Ashbury district

alarmed the San Francisco authorities, whose public warning was that

they would keep hippies away. Adam Kneeman, a long-time resident of the

Haight-Ashbury, recalls that the police did little to help the hordes of

newcomers, much of which was done by residents of the area.

College and high-school students began streaming into the Haight during the

spring break

of 1967 and the local government officials, determined to stop the

influx of young people once schools ended for the summer, unwittingly

brought additional attention to the scene, and a series of articles in

local papers alerted the national media to the hippies' growing numbers.

By spring, some Haight-Ashbury residents responded by forming the

Council of the Summer of Love, giving the event a name.

Popularization

The media's coverage of hippie life in the Haight-Ashbury drew the attention of youth from all over America.

Hunter S. Thompson termed the district "Hashbury" in

The New York Times Magazine, and the activities in the area were reported almost daily.

The event was also reported by the counterculture's own media, particularly the

San Francisco Oracle, the pass-around readership of which is thought to have exceeded a half-million people that summer, and the

Berkeley Barb.

The media's reportage of the "counterculture" included other events in California, such as the

Fantasy Fair and Magic Mountain Music Festival in Marin County and the

Monterey Pop Festival,

both during June 1967. At Monterey, approximately 30,000 people

gathered for the first day of the music festival, with the number

increasing to 60,000 on the final day.

Additionally, media coverage of the Monterey Pop Festival facilitated

the Summer of Love as large numbers of hippies traveled to California to

hear favorite bands such as

The Who,

Grateful Dead,

the Animals,

Jefferson Airplane,

Quicksilver Messenger Service,

The Jimi Hendrix Experience,

Otis Redding,

The Byrds, and

Big Brother and the Holding Company featuring

Janis Joplin.

"San Francisco (Be Sure to Wear Flowers in Your Hair)"

Events

New York City

In Manhattan, near the Greenwich Village neighborhood, during a concert in

Tompkins Square Park on Memorial Day of 1967, some police officers asked for the music's volume to be reduced. In response, some people in the crowd threw various objects, and 38 arrests ensued. A debate about the "threat of the hippie" ensued between Mayor

John Lindsay and Police Commissioner Howard Leary. After this event, Allan Katzman, the editor of the

East Village Other, predicted that 50,000 hippies would enter the area for the summer.

California

Double

that amount, as many as 100,000 young people from around the world,

flocked to San Francisco's Haight-Ashbury district, as well as to nearby

Berkeley and to other

San Francisco Bay Area cities, to join in a popularized version of the hippieism. A

Free Clinic was established for free medical treatment, and a

Free Store gave away basic necessities without charge to anyone who needed them.

The Summer of Love attracted a wide range of people of various

ages: teenagers and college students drawn by their peers and the allure

of joining an alleged cultural utopia; middle-class vacationers; and

even partying military personnel from bases within driving distance. The

Haight-Ashbury could not accommodate this influx of people, and the

neighborhood scene quickly deteriorated, with overcrowding,

homelessness, hunger, drug problems, and crime afflicting the

neighborhood.

Use of drugs

Haight Ashbury was a ghetto of bohemians who wanted to do

anything—and we did but I don't think it has happened since. Yes there

was LSD. But Haight Ashbury was not about drugs. It was about

exploration, finding new ways of expression, being aware of one's

existence.

After losing his untenured position as an instructor on the Psychology Faculty at

Harvard University,

Timothy Leary became a major advocate for the recreational use of psychedelic drugs. After taking

psilocybin, a drug extracted from certain

mushrooms

that causes effects similar to those of LSD, Leary endorsed the use of

all psychedelics for personal development. He often invited friends as

well as an occasional graduate student to consume such drugs along with

him and colleague

Richard Alpert.

On the West Coast, author

Ken Kesey, a prior volunteer for a

CIA-sponsored LSD experiment, also advocated the use of the drug. Soon after participating, he was inspired to write the bestselling novel

One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest.

Subsequently, after buying an old school bus, painting it with

psychedelic graffiti and attracting a group of similarly-minded

individuals he dubbed the

Merry Pranksters,

Kesey and his group traveled across the country, often hosting "acid

tests" where they would fill a large container with a diluted low dose

form of the drug and give out diplomas to those who passed their test.

Along with LSD,

cannabis

was also much used during this period. However, as a result, crime

increased among users because new laws were subsequently enacted to

control the use of both drugs. The users thereof often had sessions to

oppose the laws, including The Human Be-In referenced above as well as

various "smoke-ins" during July and August, however, their efforts at repeal were unsuccessful.

Funeral and aftermath

By the end of summer, many participants had left the scene to join the

back-to-the-land movement

of the late '60s, to resume school studies, or simply to "get a job".

Those remaining in the Haight wanted to commemorate the conclusion of

the event. A mock funeral entitled "The Death of the Hippie" ceremony

was staged on October 6, 1967, and organizer Mary Kasper explained the

intended message:

We wanted to signal that this was

the end of it, to stay where you are, bring the revolution to where you

live and don't come here because it's over and done with.

In New York, the rock musical drama

Hair, which told the story of the hippie counterculture and sexual revolution of the 1960s, began

Off-Broadway on October 17, 1967.

Legacy

Second Summer of Love

The "Second Summer of Love" (a term which generally refers to the summers of both 1988 and 1989) was a renaissance of

acid house music and rave parties in Britain. The culture supported

MDMA use and some

LSD use. The art had a generally psychedelic emotion reminiscent of the 1960s.

40th anniversary

During

the summer of 2007, San Francisco celebrated the 40th anniversary of

the Summer of Love by holding numerous events around the region,

culminating on September 2, 2007, when over 150,000 people attended the

40th anniversary of the Summer of Love concert, held in Golden Gate Park

in Speedway Meadows. It was produced by 2b1 Multimedia and the Council

of Light.

50th anniversary

In 2016, 2b1 Multimedia and The Council of Light, once again, began

the planning for the 50th Anniversary of the Summer of Love in Golden

Gate Park in San Francisco. By the beginning of 2017, the council had

gathered about 25 poster artists, about 10 of whom submitted their

finished art, but it was never printed. The council was also contacted

by many bands and musicians who wanted to be part of this historic

event, all were waiting for the date to be determined before a final

commitment.

New rules enforced by the San Francisco Parks and Recreational

Department (PRD) prohibited the council from holding a free event of the

proposed size. There were many events planned for San Francisco in

2017, many of which were 50th Anniversary-themed. However, there was no

free concert. The PRD later hosted an event originally called “Summer

Solstice Party,” but it was later renamed “50th Anniversary of the

Summer of Love” two weeks before commencement. The event had fewer than

20,000 attendees from the local Bay Area.

In frustration, producer Boots Hughston put the proposal of what

was by then to be a 52nd anniversary free concert into the form of an

initiative intended for the November 6, 2018, ballot.

The issue did not make the ballot; however, a more generic Proposition

E provides for directing hotel tax fees to a $32 million budget for

"arts and cultural organizations and projects in the city."

During the summer of 2017, San Francisco celebrated the 50th

anniversary of the Summer of Love by holding numerous events and art

exhibitions.

In Liverpool, the city has staged a 50 Summers of Love festival based on

the 50th anniversary of the June 1, 1967, release of the album

Sgt Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band, by

The Beatles.