| Herpes simplex viruses81i2 | |

|---|---|

| |

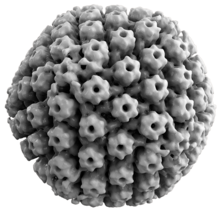

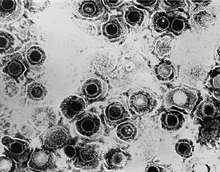

| TEM micrograph of virions of a herpes simplex virus species | |

| Scientific classification | |

| (unranked): | Virus |

| Realm: | Duplodnaviria |

| Kingdom: | Heunggongvirae |

| Phylum: | Peploviricota |

| Class: | Herviviricetes |

| Order: | Herpesvirales |

| Family: | Herpesviridae |

| Subfamily: | Alphaherpesvirinae |

| Genus: | Simplexvirus |

| Groups included | |

| Cladistically included but traditionally excluded taxa | |

All other Simplexvirus spp.:

| |

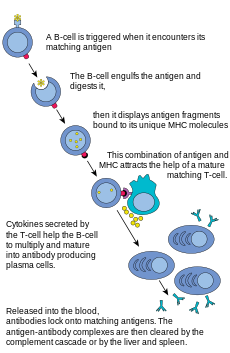

Herpes simplex virus 1 and 2 (HSV-1 and HSV-2), also known by their taxonomical names Human alphaherpesvirus 1 and Human alphaherpesvirus 2, are two members of the human Herpesviridae family, a set of new viruses that produce viral infections in the majority of humans. Both HSV-1 (which produces most cold sores) and HSV-2 (which produces most genital herpes) are common and contagious. They can be spread when an infected person begins shedding the virus.

About 67% of the world population under the age of 50 has HSV-1. In the United States, about 47.8% and 11.9% are believed to have HSV-1 and HSV-2, respectively. Because it can be transmitted through any intimate contact, it is one of the most common sexually transmitted infections.

Symptoms

Many of those who are infected never develop symptoms. Symptoms, when they occur, may include watery blisters in the skin or mucous membranes of the mouth, lips, nose, or genitals. Lesions heal with a scab

characteristic of herpetic disease. Sometimes, the viruses cause mild

or atypical symptoms during outbreaks. However, they can also cause more

troublesome forms of herpes simplex. As neurotropic and neuroinvasive viruses, HSV-1 and -2 persist in the body by hiding from the immune system in the cell bodies of neurons. After the initial or primary infection, some infected people experience sporadic

episodes of viral reactivation or outbreaks. In an outbreak, the virus

in a nerve cell becomes active and is transported via the neuron's axon to the skin, where virus replication and shedding occur and cause new sores.

Transmission

HSV-1 and HSV-2 are transmitted by contact with an infected person

who has reactivations of the virus. HSV-2 is periodically shed in the

human genital tract, most often asymptomatically. Most sexual

transmissions occur during periods of asymptomatic shedding.

Asymptomatic reactivation means that the virus causes atypical, subtle,

or hard-to-notice symptoms that are not identified as an active herpes

infection, so acquiring the virus is possible even if no active HSV

blisters or sores are present. In one study, daily genital swab samples

found HSV-2 at a median of 12–28% of days among those who have had an

outbreak, and 10% of days among those suffering from asymptomatic

infection, with many of these episodes occurring without visible

outbreak ("subclinical shedding").

In another study, 73 subjects were randomized to receive valaciclovir 1 g daily or placebo for 60 days each in a two-way crossover design.

A daily swab of the genital area was self-collected for HSV-2 detection

by polymerase chain reaction, to compare the effect of valaciclovir

versus placebo on asymptomatic viral shedding in immunocompetent, HSV-2

seropositive subjects without a history of symptomatic genital herpes

infection. The study found that valaciclovir significantly reduced

shedding during subclinical days compared to placebo, showing a 71%

reduction; 84% of subjects had no shedding while receiving valaciclovir

versus 54% of subjects on placebo. About 88% of patients treated with

valaciclovir had no recognized signs or symptoms versus 77% for placebo.

For HSV-2, subclinical shedding may account for most of the transmission.

Studies on discordant partners (one infected with HSV-2, one not) show

that the transmission rate is approximately 5 per 10,000 sexual

contacts. Atypical symptoms are often attributed to other causes, such as a yeast infection. HSV-1 is often acquired orally during childhood. It may also be sexually transmitted, including contact with saliva, such as kissing and mouth-to-genital contact (oral sex). HSV-2 is primarily a sexually transmitted infection, but rates of HSV-1 genital infections are increasing.

Both viruses may also be transmitted vertically during childbirth.

However, the risk of infection transmission is minimal if the mother

has no symptoms or exposed blisters during delivery. The risk is

considerable when the mother is infected with the virus for the first

time during late pregnancy.

Contrary to popular myths, herpes cannot be transmitted from surfaces

such as toilet seats because the herpes virus begins to die immediately

after leaving the body.

Herpes simplex viruses can affect areas of skin exposed to

contact with an infected person (although shaking hands with an infected

person does not transmit this disease). An example of this is herpetic whitlow, which is a herpes infection on the fingers. This was a common affliction of dental surgeons prior to the routine use of gloves when conducting treatment on patients.

Infection of HSV-2 increases the risk of acquiring HIV.

Virology

Viral structure

A three-dimensional reconstruction and animation of a tail-like assembly on HSV-1 capsid

3D reconstruction of the HSV-1 capsid

Herpes Simplex Virus 2

Animal herpes viruses all share some common properties. The structure

of herpes viruses consists of a relatively large, double-stranded,

linear DNA genome encased within an icosahedral protein cage called the capsid, which is wrapped in a lipid bilayer called the envelope. The envelope is joined to the capsid by means of a tegument. This complete particle is known as the virion. HSV-1 and HSV-2 each contain at least 74 genes (or open reading frames, ORFs) within their genomes, although speculation over gene crowding allows as many as 84 unique protein coding genes by 94 putative ORFs.

These genes encode a variety of proteins involved in forming the

capsid, tegument and envelope of the virus, as well as controlling the

replication and infectivity of the virus. These genes and their

functions are summarized in the table below.

The genomes of HSV-1 and HSV-2 are complex and contain two unique regions called the long unique region (UL) and the short unique region (US). Of the 74 known ORFs, UL contains 56 viral genes, whereas US contains only 12. Transcription of HSV genes is catalyzed by RNA polymerase II of the infected host. Immediate early genes,

which encode proteins that regulate the expression of early and late

viral genes, are the first to be expressed following infection. Early gene expression follows, to allow the synthesis of enzymes involved in DNA replication and the production of certain envelope glycoproteins. Expression of late genes occurs last; this group of genes predominantly encode proteins that form the virion particle.

Five proteins from (UL) form the viral capsid - UL6, UL18, UL35, UL38, and the major capsid protein UL19.

Cellular entry

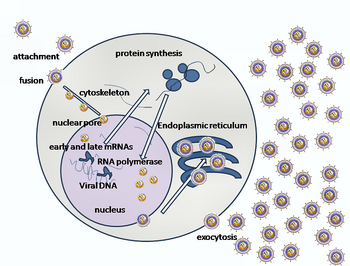

A simplified diagram of HSV replication

Entry of HSV into a host cell involves several glycoproteins on the surface of the enveloped virus binding to their transmembrane receptors

on the cell surface. Many of these receptors are then pulled inwards by

the cell, which is thought to open a ring of three gHgL heterodimers

stabilizing a compact conformation of the gB glycoprotein, so that it

springs out and punctures the cell membrane.

The envelope covering the virus particle then fuses with the cell

membrane, creating a pore through which the contents of the viral

envelope enters the host cell.

The sequential stages of HSV entry are analogous to those of other viruses.

At first, complementary receptors on the virus and the cell surface

bring the viral and cell membranes into proximity. Interactions of these

molecules then form a stable entry pore through which the viral

envelope contents are introduced to the host cell. The virus can also be

endocytosed after binding to the receptors, and the fusion could occur at the endosome. In electron micrographs, the outer leaflets of the viral and cellular lipid bilayers have been seen merged;

this hemifusion may be on the usual path to entry or it may usually be

an arrested state more likely to be captured than a transient entry

mechanism.

In the case of a herpes virus, initial interactions occur when

two viral envelope glycoprotein called glycoprotein C (gC) and

glycoprotein B (gB) bind to a cell surface particle called heparan sulfate.

Next, the major receptor binding protein, glycoprotein D (gD), binds

specifically to at least one of three known entry receptors. These cell receptors include herpesvirus entry mediator (HVEM), nectin-1

and 3-O sulfated heparan sulfate. The nectin receptors usually produce

cell-cell adhesion, to provide a strong point of attachment for the

virus to the host cell.

These interactions bring the membrane surfaces into mutual proximity

and allow for other glycoproteins embedded in the viral envelope to

interact with other cell surface molecules.

Once bound to the HVEM, gD changes its conformation and interacts with

viral glycoproteins H (gH) and L (gL), which form a complex. The

interaction of these membrane proteins may result in a hemifusion state.

gB interaction with the gH/gL complex creates an entry pore for the

viral capsid. gB interacts with glycosaminoglycans on the surface of the host cell.

Genetic inoculation

After the viral capsid enters the cellular cytoplasm, it is transported to the cell nucleus.

Once attached to the nucleus at a nuclear entry pore, the capsid ejects

its DNA contents via the capsid portal. The capsid portal is formed by

12 copies of portal protein, UL6, arranged as a ring; the proteins

contain a leucine zipper sequence of amino acids, which allow them to adhere to each other. Each icosahedral capsid contains a single portal, located in one vertex.

The DNA exits the capsid in a single linear segment.

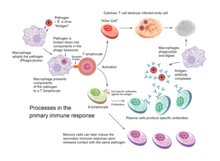

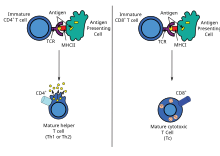

Immune evasion

HSV evades the immune system through interference with MHC class I antigen presentation on the cell surface, by blocking the transporter associated with antigen processing (TAP) induced by the secretion of ICP-47

by HSV. In the host cell, TAP transports digested viral antigen epitope

peptides from the cytosol to the endoplasmic reticulum, allowing these

epitopes to be combined with MHC class I molecules and presented on the

surface of the cell. Viral epitope presentation with MHC class I is a

requirement for activation of cytotoxic T-lymphocytes (CTLs), the major

effectors of the cell-mediated immune response against virally-infected

cells. ICP-47 prevents initiation of a CTL-response against HSV,

allowing the virus to survive for a protracted period in the host.

Replication

Micrograph showing the viral cytopathic effect of HSV (multinucleation, ground glass chromatin)

Following infection of a cell, a cascade of herpes virus proteins, called immediate-early, early, and late, is produced. Research using flow cytometry on another member of the herpes virus family, Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus, indicates the possibility of an additional lytic stage, delayed-late.

These stages of lytic infection, particularly late lytic, are distinct

from the latency stage. In the case of HSV-1, no protein products are

detected during latency, whereas they are detected during the lytic

cycle.

The early proteins transcribed are used in the regulation of

genetic replication of the virus. On entering the cell, an α-TIF protein

joins the viral particle and aids in immediate-early transcription. The virion host shutoff protein (VHS or UL41) is very important to viral replication. This enzyme shuts off protein synthesis in the host, degrades host mRNA, helps in viral replication, and regulates gene expression of viral proteins. The viral genome immediately travels to the nucleus, but the VHS protein remains in the cytoplasm.

The late proteins form the capsid and the receptors on the

surface of the virus. Packaging of the viral particles — including the genome, core and the capsid - occurs in the nucleus of the cell. Here, concatemers

of the viral genome are separated by cleavage and are placed into

formed capsids. HSV-1 undergoes a process of primary and secondary

envelopment. The primary envelope is acquired by budding into the inner

nuclear membrane of the cell. This then fuses with the outer nuclear

membrane, releasing a naked capsid into the cytoplasm. The virus

acquires its final envelope by budding into cytoplasmic vesicles.

Latent infection

HSVs may persist in a quiescent but persistent form known as latent infection, notably in neural ganglia. HSV-1 tends to reside in the trigeminal ganglia, while HSV-2 tends to reside in the sacral ganglia, but these are tendencies only, not fixed behavior. During latent infection of a cell, HSVs express latency-associated transcript (LAT) RNA.

LAT regulates the host cell genome and interferes with natural cell

death mechanisms. By maintaining the host cells, LAT expression

preserves a reservoir of the virus, which allows subsequent, usually

symptomatic, periodic recurrences or "outbreaks" characteristic of

nonlatency. Whether or not recurrences are symptomatic, viral shedding

occurs to infect a new host.

A protein found in neurons may bind to herpes virus DNA and regulate latency. Herpes virus DNA contains a gene for a protein called ICP4, which is an important transactivator of genes associated with lytic infection in HSV-1.

Elements surrounding the gene for ICP4 bind a protein known as the

human neuronal protein neuronal restrictive silencing factor (NRSF) or human repressor element silencing transcription factor (REST). When bound to the viral DNA elements, histone deacetylation occurs atop the ICP4

gene sequence to prevent initiation of transcription from this gene,

thereby preventing transcription of other viral genes involved in the

lytic cycle. Another HSV protein reverses the inhibition of ICP4 protein synthesis. ICP0 dissociates NRSF from the ICP4 gene and thus prevents silencing of the viral DNA.

Genome

The HSV genome consists of two unique segments, named unique long (UL) and unique short (US), as well as terminal inverted repeats

found to the two ends of them named repeat long (RL) and repeat short

(RS). There are also minor "terminal redundancy" (α) elements found on

the further ends of RS. The overall arrangement is RL-UL-RL-α-RS-US-RS-α

with each pair of repeats inverting each other. The whole sequence is

then encapsuled in a terminal direct repeat. The long and short parts

each have their own origins of replication, with OriL located between UL28 and UL30 and OriS located in a pair nearthe RS.

As the L and S segments can be assembled in any direction, they can be

inverted relative to each other freely, forming various linear isomers.

| ORF | Protein alias | HSV-1 | HSV-2 | Function/description |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Repeat long (RL) | ||||

| ICP0/RL2 | ICP0; IE110; α0 | P08393 | P28284 | E3 ubiquitin ligase that activates viral gene transcription by opposing chromatinization of the viral genome and counteracts intrinsic- and interferon-based antiviral responses. |

| RL1 | RL1; ICP34.5 | O12396 | Neurovirulence factor. Antagonizes PKR by de-phosphorylating eIF4a. Binds to BECN1 and inactivates autophagy. | |

| LAT | LRP1, LRP2 | P17588 P17589 |

Latency-associated transcript abd protein products (latency-related protein) | |

| Unique long (UL) | ||||

| UL1 | Glycoprotein L | P10185 |

|

Surface and membrane |

| UL2 | UL2 | P10186 |

|

Uracil-DNA glycosylase |

| UL3 | UL3 | P10187 |

|

unknown |

| UL4 | UL4 | P10188 |

|

unknown |

| UL5 | UL5 | Q2MGV2 |

|

DNA replication |

| UL6 | Portal protein UL-6 | P10190 |

|

Twelve of these proteins constitute the capsid portal ring through which DNA enters and exits the capsid |

| UL7 | UL7 | P10191 |

|

Virion maturation |

| UL8 | UL8 | P10192 |

|

DNA virus helicase-primase complex-associated protein |

| UL9 | UL9 | P10193 |

|

Replication origin-binding protein |

| UL10 | Glycoprotein M | P04288 |

|

Surface and membrane |

| UL11 | UL11 | P04289 |

|

virion exit and secondary envelopment |

| UL12 | UL12 | Q68978 |

|

Alkaline exonuclease |

| UL13 | UL13 | Q9QNF2 |

|

Serine-threonine protein kinase |

| UL14 | UL14 | P04291 |

|

Tegument protein |

| UL15 | Terminase | P04295 |

|

Processing and packaging of DNA |

| UL16 | UL16 | P10200 |

|

Tegument protein |

| UL17 | UL17 | P10201 |

|

Processing and packaging DNA |

| UL18 | VP23 | P10202 |

|

Capsid protein |

| UL19 | VP5 | P06491 |

|

Major capsid protein |

| UL20 | UL20 | P10204 |

|

Membrane protein |

| UL21 | UL21 | P10205 |

|

Tegument protein |

| UL22 | Glycoprotein H | P06477 |

|

Surface and membrane |

| UL23 | Thymidine kinase | O55259 |

|

Peripheral to DNA replication |

| UL24 | UL24 | P10208 |

|

unknown |

| UL25 | UL25 | P10209 |

|

Processing and packaging DNA |

| UL26 | P40; VP24; VP22A; UL26.5 (HHV2 short isoform) | P10210 | P89449 | Capsid protein |

| UL27 | Glycoprotein B | A1Z0P5 |

|

Surface and membrane |

| UL28 | ICP18.5 | P10212 |

|

Processing and packaging DNA |

| UL29 | UL29; ICP8 | Q2MGU6 |

|

Major DNA-binding protein |

| UL30 | DNA polymerase | Q4ACM2 |

|

DNA replication |

| UL31 | UL31 | Q25BX0 |

|

Nuclear matrix protein |

| UL32 | UL32 | P10216 |

|

Envelope glycoprotein |

| UL33 | UL33 | P10217 |

|

Processing and packaging DNA |

| UL34 | UL34 | P10218 |

|

Inner nuclear membrane protein |

| UL35 | VP26 | P10219 |

|

Capsid protein |

| UL36 | UL36 | P10220 |

|

Large tegument protein |

| UL37 | UL37 | P10216 |

|

Capsid assembly |

| UL38 | UL38; VP19C | P32888 | Capsid assembly and DNA maturation | |

| UL39 | UL39; RR-1; ICP6 | P08543 | Ribonucleotide reductase (large subunit) | |

| UL40 | UL40; RR-2 | P06474 | Ribonucleotide reductase (small subunit) | |

| UL41 | UL41; VHS | P10225 | Tegument protein; virion host shutoff | |

| UL42 | UL42 | Q4H1G9 | DNA polymerase processivity factor | |

| UL43 | UL43 | P10227 | Membrane protein | |

| UL44 | Glycoprotein C | P10228 | Surface and membrane | |

| UL45 | UL45 | P10229 | Membrane protein; C-type lectin | |

| UL46 | VP11/12 | P08314 | Tegument proteins | |

| UL47 | UL47; VP13/14 | P10231 | Tegument protein | |

| UL48 | VP16 (Alpha-TIF) | P04486 | Virion maturation; activate IE genes by interacting with the cellular transcription factors Oct-1 and HCF. Binds to the sequence 5'TAATGARAT3'. | |

| UL49 | UL49A | O09800 | Envelope protein | |

| UL50 | UL50 | P10234 | dUTP diphosphatase | |

| UL51 | UL51 | P10234 | Tegument protein | |

| UL52 | UL52 | P10236 | DNA helicase/primase complex protein | |

| UL53 | Glycoprotein K | P68333 | Surface and membrane | |

| UL54 | IE63; ICP27 | P10238 | Transcriptional regulation and inhibition of the STING signalsome | |

| UL55 | UL55 | P10239 | Unknown | |

| UL56 | UL56 | P10240 | Unknown | |

| Inverted repeat long (IRL) | ||||

| Inverted repeat short (IRS) | ||||

| Unique short (US) | ||||

| US1 | ICP22; IE68 | P04485 | Viral replication | |

| US2 | US2 | P06485 | Unknown | |

| US3 | US3 | P04413 | Serine/threonine-protein kinase | |

| US4 | Glycoprotein G | P06484 | Surface and membrane | |

| US5 | Glycoprotein J | P06480 | Surface and membrane | |

| US6 | Glycoprotein D | A1Z0Q5 | Surface and membrane | |

| US7 | Glycoprotein I | P06487 | Surface and membrane | |

| US8 | Glycoprotein E | Q703F0 | Surface and membrane | |

| US9 | US9 | P06481 | Tegument protein | |

| US10 | US10 | P06486 | Capsid/Tegument protein | |

| US11 | US11; Vmw21 | P56958 | Binds DNA and RNA | |

| US12 | Infected cell protein 47|ICP47; IE12 | P03170 | Inhibits MHC class I pathway by preventing binding of antigen to TAP | |

| Terminal repeat short (TRS) | ||||

| RS1 | ICP4; IE175 | P08392 | Major transcriptional activator. Essential for progression beyond the immediate-early phase of infection. IEG transcription repressor. | |

Evolution

The herpes simplex 1 genomes can be classified into six clades. Four of these occur in East Africa, one in East Asia and one in Europe and North America. This suggests that the virus may have originated in East Africa. The most recent common ancestor of the Eurasian strains appears to have evolved ~60,000 years ago.

The East Asian HSV-1 isolates have an unusual pattern that is currently

best explained by the two waves of migration responsible for the

peopling of Japan. Herpes simplex 2 genomes can be divided into two groups: one is globally distributed and the other is mostly limited to sub Saharan Africa. The globably distributed genotype

has undergone four ancient recombinations with herpes simplex 1. It has

also been reported that HSV-1 and HSV-2 can have contemporary and

stable recombination events in hosts simultaneously infected with both

pathogens. All of the cases are HSV-2 acquiring parts of the HSV-1

genome, sometimes changing parts of its antigen epitope in the process.

The mutation rate has been estimated to be ~1.38×10−7 substitutions/site/year.[45] In clinical setting, the mutations in either the thymidine kinase gene or DNA polymerase gene has caused resistance to aciclovir. However, most of the mutations occur in the thymidine kinase gene rather than the DNA polymerase gene.

Another analysis has estimated the mutation rate in the herpes simplex 1 genome to be 1.82×10−8

nucleotide substitution per site per year. This analysis placed the

most recent common ancestor of this virus ~710,000 years ago.

Herpes simplex 1 and 2 diverged about 6 million years ago.

Treatment

The herpes viruses establish lifelong infections (thus cannot be eradicated from the body). Because the virus is a foreign pathogen, a human body's immune system as well as its specialty antigen naturally diminishes the virus.

Treatment usually involves general-purpose antiviral drugs

that interfere with viral replication, reduce the physical severity of

outbreak-associated lesions, and lower the chance of transmission to

others. Studies of vulnerable patient populations have indicated that

daily use of antivirals such as aciclovir and valaciclovir can reduce reactivation rates. The extensive use of antiherpetic drugs has led to the development of drug resistance,

which in turn leads to treatment failure. Therefore, new sources of

drugs are broadly investigated to defeat the problem. In January 2020, a

comprehensive review article was published that demonstrated the

effectiveness of natural products as promising anti-HSV drugs.

Pyrithione, a Zinc Ionophore, show antiviral activity against Herpes simplex virus.

Alzheimer's disease

It was reported, in 1979, that there is a possible link between HSV-1 and Alzheimer's disease, in people with the epsilon4 allele of the gene APOE.

HSV-1 appears to be particularly damaging to the nervous system and

increases one's risk of developing Alzheimer's disease. The virus

interacts with the components and receptors of lipoproteins, which may lead to the development of Alzheimer's disease. This research identifies HSVs as the pathogen most clearly linked to the establishment of Alzheimer's. According to a study done in 1997, without the presence of the gene allele, HSV-1 does not appear to cause any neurological damage or increase the risk of Alzheimer's.

However, a more recent prospective study published in 2008 with a

cohort of 591 people showed a statistically significant difference

between patients with antibodies indicating recent reactivation of HSV

and those without these antibodies in the incidence of Alzheimer's

disease, without direct correlation to the APOE-epsilon4 allele.

The trial had a small sample of patients who did not have the

antibody at baseline, so the results should be viewed as highly

uncertain. In 2011 Manchester University scientists showed that treating

HSV1-infected cells with antiviral agents decreased the accumulation of

β-amyloid and tau protein, and also decreased HSV-1 replication.

A 2018 retrospective study from Taiwan

on 33,000 patients found that being infected with herpes simplex virus

increased the risk of dementia 2.56 times (95% CI: 2.3-2.8) in patients

not receiving anti-herpetic medications (2.6 times for HSV-1 infections

and 2.0 times for HSV-2 infections). However, HSV-infected patients

who were receiving anti-herpetic medications (acyclovir, famciclovir,

ganciclovir, idoxuridine, penciclovir, tromantadine, valaciclovir, or

valganciclovir) showed no elevated risk of dementia compared to patients

uninfected with HSV.

Multiplicity reactivation

Multiplicity

reactivation (MR) is the process by which viral genomes containing

inactivating damage interact within an infected cell to form a viable

viral genome. MR was originally discovered with the bacterial virus

bacteriophage T4, but was subsequently also found with pathogenic

viruses including influenza virus, HIV-1, adenovirus simian virus 40,

vaccinia virus, reovirus, poliovirus and herpes simplex virus.

When HSV particles are exposed to doses of a DNA damaging agent

that would be lethal in single infections, but are then allowed to

undergo multiple infection (i.e. two or more viruses per host cell), MR

is observed. Enhanced survival of HSV-1 due to MR occurs upon exposure

to different DNA damaging agents, including methyl methanesulfonate, trimethylpsoralen (which causes inter-strand DNA cross-links), and UV light.

After treatment of genetically marked HSV with trimethylpsoralen,

recombination between the marked viruses increases, suggesting that

trimethylpsoralen damage stimulates recombination.

MR of HSV appears to partially depend on the host cell recombinational

repair machinery since skin fibroblast cells defective in a component of

this machinery (i.e. cells from Bloom's syndrome patients) are

deficient in MR.

These observations suggest that MR in HSV infections involves

genetic recombination between damaged viral genomes resulting in

production of viable progeny viruses. HSV-1, upon infecting host cells,

induces inflammation and oxidative stress.

Thus it appears that the HSV genome may be subjected to oxidative DNA

damage during infection, and that MR may enhance viral survival and

virulence under these conditions.

Use as an anti-cancer agent

Modified Herpes simplex virus is considered as a potential therapy for cancer and has been extensively clinically tested to assess its oncolytic (cancer killing) ability. Interim overall survival data from Amgen's phase 3 trial of a genetically-attenuated herpes virus suggests efficacy against melanoma.

Use in neuronal connection tracing

Herpes simplex virus is also used as a transneuronal tracer defining connections among neurons by virtue of traversing synapses.

Herpes simplex virus is likely the most common cause of Mollaret's meningitis. In worst-case scenarios, it can lead to a potentially fatal case of herpes simplex encephalitis.

Research

There exist commonly used vaccines to some herpesviruses, but only veterinary, such as HVT/LT (Turkey herpesvirus vector laryngotracheitis vaccine). However, it prevents atherosclerosis (which histologically mirrors atherosclerosis in humans) in target animals vaccinated.