Geothermal power is electrical power generated from geothermal energy. Technologies in use include dry steam power stations, flash steam power stations and binary cycle power stations. Geothermal electricity generation is currently used in 26 countries, while geothermal heating is in use in 70 countries.

As of 2019, worldwide geothermal power capacity amounts to 15.4 gigawatts (GW), of which 23.9% (3.68 GW) are installed in the United States. International markets grew at an average annual rate of 5 percent over the three years to 2015, and global geothermal power capacity is expected to reach 14.5–17.6 GW by 2020. Based on current geologic knowledge and technology the Geothermal Energy Association (GEA) publicly discloses, the GEA estimates that only 6.9% of total global potential has been tapped so far, while the IPCC reported geothermal power potential to be in the range of 35 GW to 2 TW. Countries generating more than 15 percent of their electricity from geothermal sources include El Salvador, Kenya, the Philippines, Iceland, New Zealand, and Costa Rica. Indonesia has an estimated potential of 29 GW of geothermal energy resources, the largest in the world; in 2017, its installed capacity was 1.8 GW.

Geothermal power is considered to be a sustainable, renewable source of energy because the heat extraction is small compared with the Earth's heat content. The greenhouse gas emissions of geothermal electric stations average 45 grams of carbon dioxide per kilowatt-hour of electricity, or less than 5% of those of conventional coal-fired plants.

As a source of renewable energy for both power and heating,

geothermal has the potential to meet 3 to 5% of global demand by 2050.

With economic incentives, it is estimated that by 2100 it will be possible to meet 10% of global demand with geothermal power.

History and development

In the 20th century, demand for electricity led to the consideration of geothermal power as a generating source. Prince Piero Ginori Conti tested the first geothermal power generator on 4 July 1904 in Larderello, Italy. It successfully lit four light bulbs. Later, in 1911, the world's first commercial geothermal power station was built there. Experimental generators were built in Beppu, Japan and the Geysers, California, in the 1920s, but Italy was the world's only industrial producer of geothermal electricity until 1958.

In 1958, New Zealand became the second major industrial producer of geothermal electricity when its Wairakei station was commissioned. Wairakei was the first station to use flash steam technology. Over the past 60 years, net fluid production has been in excess of 2.5 km3. Subsidence

at Wairakei-Tauhara has been an issue in a number of formal hearings

related to environmental consents for expanded development of the system

as a source of renewable energy.

In 1960, Pacific Gas and Electric began operation of the first successful geothermal electric power station in the United States at The Geysers in California. The original turbine lasted for more than 30 years and produced 11 MW net power.

An organic fluid based binary cycle power station was first demonstrated in 1967 in the Soviet Union and later introduced to the United States in 1981, following the 1970s energy crisis

and significant changes in regulatory policies. This technology allows

the use of temperature resources as low as 81 °C (178 °F). In 2006, a

binary cycle station in Chena Hot Springs, Alaska, came on-line, producing electricity from a record low fluid temperature of 57 °C (135 °F).

Geothermal electric stations have until recently been built

exclusively where high-temperature geothermal resources are available

near the surface. The development of binary cycle power plants and improvements in drilling and extraction technology may enable enhanced geothermal systems over a much greater geographical range. Demonstration projects are operational in Landau-Pfalz, Germany, and Soultz-sous-Forêts, France, while an earlier effort in Basel, Switzerland was shut down after it triggered earthquakes. Other demonstration projects are under construction in Australia, the United Kingdom, and the United States of America.

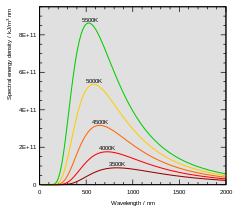

The thermal efficiency of geothermal electric stations is low, around 7 to 10%, because geothermal fluids are at a low temperature compared with steam from boilers. By the laws of thermodynamics this low temperature limits the efficiency of heat engines

in extracting useful energy during the generation of electricity.

Exhaust heat is wasted, unless it can be used directly and locally, for

example in greenhouses, timber mills, and district heating. The

efficiency of the system does not affect operational costs as it would

for a coal or other fossil fuel plant, but it does factor into the

viability of the station. In order to produce more energy than the pumps

consume, electricity generation requires high-temperature geothermal

fields and specialized heat cycles. Because geothermal power does not rely on variable sources of energy, unlike, for example, wind or solar, its capacity factor can be quite large – up to 96% has been demonstrated. However the global average capacity factor was 74.5% in 2008, according to the IPCC.

Resources

The Earth's heat content is about 1×1019 TJ (2.8×1015 TWh). This heat naturally flows to the surface by conduction at a rate of 44.2 TW and is replenished by radioactive decay at a rate of 30 TW. These power rates are more than double humanity's current energy consumption from primary sources, but most of this power is too diffuse (approximately 0.1 W/m2 on average) to be recoverable. The Earth's crust effectively acts as a thick insulating blanket which must be pierced by fluid conduits (of magma, water or other) to release the heat underneath.

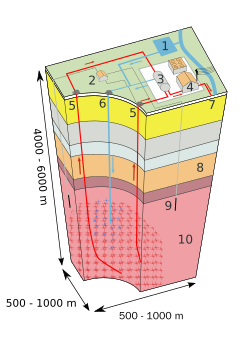

Electricity generation requires high-temperature resources that can only come from deep underground. The heat must be carried to the surface by fluid circulation, either through magma conduits, hot springs, hydrothermal circulation, oil wells, drilled water wells, or a combination of these. This circulation sometimes exists naturally where the crust is thin: magma conduits bring heat close to the surface, and hot springs bring the heat to the surface. If a hot spring is not available, a well must be drilled into a hot aquifer. Away from tectonic plate boundaries the geothermal gradient is 25 to 30 °C per kilometre (70 to 85 °F per mile) of depth in most of the world, so wells would have to be several kilometres deep to permit electricity generation. The quantity and quality of recoverable resources improves with drilling depth and proximity to tectonic plate boundaries.

In ground that is hot but dry, or where water pressure is

inadequate, injected fluid can stimulate production. Developers bore two

holes into a candidate site, and fracture the rock between them with

explosives or high-pressure water. Then they pump water or liquefied carbon dioxide down one borehole, and it comes up the other borehole as a gas. This approach is called hot dry rock geothermal energy in Europe, or enhanced geothermal systems

in North America. Much greater potential may be available from this

approach than from conventional tapping of natural aquifers.

Estimates of the electricity generating potential of geothermal

energy vary from 35 to 2000 GW depending on the scale of investments.

This does not include non-electric heat recovered by co-generation,

geothermal heat pumps and other direct use. A 2006 report by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology

(MIT) that included the potential of enhanced geothermal systems

estimated that investing US$1 billion in research and development over

15 years would allow the creation of 100 GW of electrical generating

capacity by 2050 in the United States alone. The MIT report estimated that over 200×109 TJ (200 ZJ; 5.6×107 TWh)

would be extractable, with the potential to increase this to over

2,000 ZJ with technology improvements – sufficient to provide all the

world's present energy needs for several millennia.

At present, geothermal wells are rarely more than 3 km (2 mi) deep. Upper estimates of geothermal resources assume wells as deep as 10 km (6 mi). Drilling near this depth is now possible in the petroleum industry, although it is an expensive process. The deepest research well in the world, the Kola Superdeep Borehole (KSDB-3), is 12.261 km (7.619 mi) deep. Wells drilled to depths greater than 4 km (2.5 mi) generally incur drilling costs in the tens of millions of dollars. The technological challenges are to drill wide bores at low cost and to break larger volumes of rock.

Geothermal power is considered to be sustainable because the heat

extraction is small compared to the Earth's heat content, but

extraction must still be monitored to avoid local depletion.

Although geothermal sites are capable of providing heat for many

decades, individual wells may cool down or run out of water. The three

oldest sites, at Larderello, Wairakei,

and the Geysers have all reduced production from their peaks. It is not

clear whether these stations extracted energy faster than it was

replenished from greater depths, or whether the aquifers supplying them

are being depleted. If production is reduced, and water is reinjected,

these wells could theoretically recover their full potential. Such

mitigation strategies have already been implemented at some sites. The

long-term sustainability of geothermal energy has been demonstrated at

the Larderello field in Italy since 1913, at the Wairakei field in New

Zealand since 1958, and at the Geysers field in California since 1960.

Power station types

Geothermal power stations are similar to other steam turbine thermal power stations in that heat from a fuel source (in geothermal's case, the Earth's core) is used to heat water or another working fluid. The working fluid is then used to turn a turbine of a generator, thereby producing electricity. The fluid is then cooled and returned to the heat source.

Dry steam power stations

Dry

steam stations are the simplest and oldest design. There are few power

stations of this type, because they require a resource that produces dry steam, but they are the most efficient, with the simplest facilities. At these sites, there may be liquid water present in the reservoir, but only steam, not water, is produced to the surface. Dry steam power directly uses geothermal steam of 150 °C (300 °F) or greater to turn turbines. As the turbine rotates it powers a generator that produces electricity and adds to the power field. Then, the steam is emitted to a condenser, where it turns back into a liquid, which then cools the water.

After the water is cooled it flows down a pipe that conducts the

condensate back into deep wells, where it can be reheated and produced

again. At The Geysers

in California, after the first 30 years of power production, the steam

supply had depleted and generation was substantially reduced. To restore

some of the former capacity, supplemental water injection was developed

during the 1990s and 2000s, including utilization of effluent from

nearby municipal sewage treatment facilities.

Flash steam power stations

Flash steam stations pull deep, high-pressure hot water into lower-pressure tanks and use the resulting flashed steam to drive turbines. They require fluid temperatures of at least 180 °C (360 °F), usually more. As of 2022, flash steam stations account for 36.7% of all geothermal power plants and 52.7% of the installed capacity in the world. Flash steam plants use geothermal reservoirs of water with temperatures greater than 180 °C. The hot water flows up through wells in the ground under its own pressure. As it flows upward, the pressure decreases and some of the hot water is transformed into steam. The steam is then separated from the water and used to power a turbine/generator. Any leftover water and condensed steam may be injected back into the reservoir, making this a potentially sustainable resource.

Binary cycle power stations

Binary cycle power stations are the most recent development, and can accept fluid temperatures as low as 57 °C (135 °F).

The moderately hot geothermal water is passed by a secondary fluid with

a much lower boiling point than water. This causes the secondary fluid

to flash vaporize, which then drives the turbines. This is the most

common type of geothermal electricity station being constructed today. Both Organic Rankine and Kalina cycles are used. The thermal efficiency of this type of station is typically about 10–13%.

Binary cycle power plants have an average unit capacity of 6.3 MW, 30.4

MW at single-flash power plants, 37.4 MW at double-flash plants, and

45.4 MW at power plants working on superheated steam.

Worldwide production

The International Renewable Energy Agency has reported that 14,438 MW of geothermal power was online worldwide at the end of 2020, generating 94,949 GWh of electricity.

In theory, the world's geothermal resources are sufficient to supply

humans with energy. However, only a tiny fraction of the world's

geothermal resources can at present be explored on a profitable basis.

Al Gore

said in The Climate Project Asia Pacific Summit that Indonesia could

become a super power country in electricity production from geothermal

energy. In 2013 the publicly owned electricity sector in India announced a plan to develop the country's first geothermal power facility in the landlocked state of Chhattisgarh.

Geothermal power in Canada has high potential due to its position on the Pacific Ring of Fire. The region of greatest potential is the Canadian Cordillera, stretching from British Columbia to the Yukon, where estimates of generating output have ranged from 1,550 MW to 5,000 MW.

The geography of Japan is uniquely suited for geothermal power production. Japan has numerous hot springs that could provide fuel for geothermal power plants, but a massive investment in Japan's infrastructure would be necessary.

Utility-grade stations

The largest group of geothermal power plants in the world is located at The Geysers, a geothermal field in California, United States. As of 2021, five countries (Kenya, Iceland, El Salvador, New Zealand, and Nicaragua) generate more than 15% of their electricity from geothermal sources.

The following table lists these data for each country:

- total generation from geothermal in terawatt-hours,

- percent of that country's generation that was geothermal,

- total geothermal capacity in gigawatts,

- percent growth in geothermal capacity, and

- the geothermal capacity factor for that year.

Data are for the year 2021. Data are sourced from the EIA. Only includes countries with more than 0.01 TWh of generation. Links for each location go to the relevant geothermal power page, when available.

| Country | Gen (TWh) |

% gen. |

Cap. (GW) |

% cap. growth |

Cap. fac. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| World | 91.80 | 0.3% | 14.67 | 1.7 | 71% |

| 16.24 | 0.4% | 2.60 | 1.0 | 71% | |

| 15.90 | 5.2% | 2.28 | 6.9 | 80% | |

| 10.89 | 10.1% | 1.93 | 0 | 64% | |

| 10.77 | 3.4% | 1.68 | 3.9 | 73% | |

| 7.82 | 18.0% | 1.27 | 0 | 70% | |

| 5.68 | 29.4% | 0.76 | 0 | 86% | |

| 5.53 | 2.0% | 0.77 | 0 | 82% | |

| 5.12 | 43.4% | 0.86 | 0 | 68% | |

| 4.28 | 1.3% | 1.03 | 0 | 47% | |

| 3.02 | 0.3% | 0.48 | 0 | 72% | |

| 1.60 | 12.6% | 0.26 | 0 | 70% | |

| 1.58 | 23.9% | 0.20 | 0 | 88% | |

| 0.78 | 16.9% | 0.15 | 0 | 58% | |

| 0.45 | 0.04% | 0.07 | 0 | 69% | |

| 0.40 | 8.2% | 0.06 | 0 | 82% | |

| 0.33 | 0.4% | 0.04 | 0 | 94% | |

| 0.32 | 2.2% | 0.05 | 0 | 73% | |

| 0.31 | 2.6% | 0.04 | 0 | 91% | |

| 0.25 | 0.04% | 0.05 | 15.0 | 62% | |

| 0.18 | 0.4% | 0.03 | 0 | 70% | |

| 0.13 | 0.03% | 0.02 | 0 | 95% | |

| 0.13 | 0.002% | 0.03 | 0 | 55% | |

| 0.07 | 0.5% | 0.01 | 0 | 85% |

Environmental impact

Existing geothermal electric stations that fall within the 50th percentile of all total life cycle emissions studies reviewed by the IPCC produce on average 45 kg of CO

2 equivalent emissions per megawatt-hour of generated electricity (kg CO

2eq/MWh). For comparison, a coal-fired power plant emits 1,001 kg of CO

2 equivalent per megawatt-hour when not coupled with carbon capture and storage (CCS).

As many geothermal projects are situated in volcanically active areas

that naturally emit greenhouse gases, it is hypothesized that geothermal

plants may actually decrease the rate of de-gassing by reducing the

pressure on underground reservoirs.

Stations that experience high levels of acids and volatile chemicals are usually equipped with emission-control systems to reduce the exhaust. Geothermal stations can also inject these gases back into the earth as a form of carbon capture and storage, such as in New Zealand and in the CarbFix project in Iceland.

Other stations, like the Kızıldere geothermal power plant, exhibit the capability to use geothermal fluids to process carbon dioxide gas into dry ice at two nearby plants, resulting in very little environmental impact.

In addition to dissolved gases, hot water from geothermal sources may hold in solution trace amounts of toxic chemicals, such as mercury, arsenic, boron, antimony, and salt. These chemicals come out of solution as the water cools, and can cause environmental damage if released. The modern practice of injecting geothermal fluids back into the Earth to stimulate production has the side benefit of reducing this environmental risk.

Station construction can adversely affect land stability. Subsidence has occurred in the Wairakei field in New Zealand. Enhanced geothermal systems can trigger earthquakes due to water injection. The project in Basel, Switzerland was suspended because more than 10,000 seismic events measuring up to 3.4 on the Richter Scale occurred over the first 6 days of water injection. The risk of geothermal drilling leading to uplift has been experienced in Staufen im Breisgau.

Geothermal has minimal land and freshwater requirements. Geothermal stations use 404 square meters per GWh versus 3,632 and 1,335 square meters for coal facilities and wind farms respectively. They use 20 litres of freshwater per MWh versus over 1000 litres per MWh for nuclear, coal, or oil.

Local climate cooling is possible as a result of the work of the

geothermal circulation systems. However, according to an estimation

given by Leningrad Mining Institute in 1980s, possible cool-down will be negligible compared to natural climate fluctuations.

While volcanic activity produces geothermal energy, it is also risky. As of 2022 the Puna Geothermal Venture has still not returned to full capacity after the 2018 lower Puna eruption.

Economics

Geothermal power requires no fuel; it is therefore immune to fuel cost fluctuations. However, capital costs

tend to be high. Drilling accounts for over half the costs, and

exploration of deep resources entails significant risks. A typical well

doublet in Nevada can support 4.5 MW of electricity generation and costs

about $10 million to drill, with a 20% failure rate.

In total, electrical station construction and well drilling costs about 2–5 million € per MW of electrical capacity, while the levelised energy cost is 0.04–0.10 € per kWh.

Enhanced geothermal systems tend to be on the high side of these

ranges, with capital costs above $4 million per MW and levelized costs

above $0.054 per kWh in 2007.

Research suggests in-reservoir storage could increase the economic viability of enhanced geothermal systems in energy systems with a large share of variable renewable energy sources.

Geothermal power is highly scalable: a small power station can supply a rural village, though initial capital costs can be high.

The most developed geothermal field is the Geysers in California. In 2008, this field supported 15 stations, all owned by Calpine, with a total generating capacity of 725 MW.