Immigration to Europe has a long history, but increased substantially in the later 20th century. Western Europe countries, especially, saw high growth in immigration after World War II and many European nations today (particularly those of the EU-15) have sizeable immigrant populations, both of European and non-European origin. In contemporary globalization, migrations to Europe have accelerated in speed and scale. Over the last decades, there has been an increase in negative attitudes towards immigration, and many studies have emphasized marked differences in the strength of anti-immigrant attitudes among European countries.

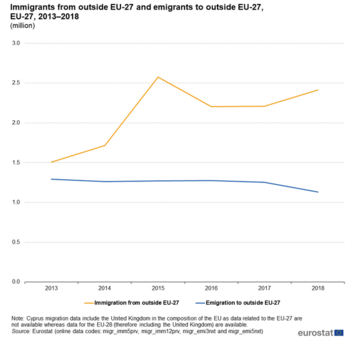

Beginning in 2004, the European Union has granted EU citizens a freedom of movement and residence within the EU, and the term "immigrant" has since been used to refer to non-EU citizens, meaning that EU citizens are not to be defined as immigrants within the EU territory. The European Commission defines "immigration" as the action by which a person from a non-EU country establishes his or her usual residence in the territory of an EU country for a period that is or is expected to be at least twelve months. Between 2010 and 2013, around 1.4 million non-EU nationals, excluding asylum seekers and refugees, immigrated into the EU each year using regular means, with a slight decrease since 2010.

History

Historical migration into or within Europe has mostly taken the form of military invasion, but there have been exceptions; this concerns notably population movements within the Roman Empire under the Pax Romana; the Jewish diaspora in Europe was the result of the First Jewish–Roman War of AD 66–73.

With the collapse of the Roman Empire, migration was again mostly coupled with warlike invasion, not least during the so-called Migration period (Germanic), the Slavic migrations, the Hungarian conquest of the Carpathian Basin, the Islamic conquests and the Turkic expansion into Eastern Europe (Kipchaks, Tatars, Cumans). The Ottomans once again established a multi-ethnic imperial structure across Western Asia and Southeastern Europe, but Turkification in Southeastern Europe was due more to cultural assimilation than to mass immigration. In the late medieval period, the Romani people moved into Europe both via Anatolia and the Maghreb.

There were substantial population movements within Europe throughout the Early Modern period, mostly in the context of the Reformation and the European wars of religion, and again as a result of World War II.

From the late 15th century until the late 1960s and early 1970s, Greece, Ireland, Italy, Germany, Norway, Sweden, Denmark, Belgium, Portugal, Spain and the United Kingdom were primarily sources of emigration, sending large numbers of emigrants to the Americas, Australia, Siberia and Southern Africa. A number also went to other European countries (notably France, Switzerland, Germany and Belgium). As living standards in these countries have risen, the trend has reversed and they were a magnet for immigration (most notably from Morocco, Somalia, Egypt to Italy and Greece; from Morocco, Algeria and Latin America to Spain and Portugal; and from Ireland, India, Pakistan, Germany, the United States, Bangladesh, and Jamaica to the United Kingdom).

Migration within Europe after the 1985 Schengen Agreement

As a result of the Schengen Agreement, signed on June 14, 1985, there is free travel within part of Europe — known as the Schengen area — for all citizens and residents of all 27 member states; however, non-citizens may only do so for tourism purpose, and for up to three months. Moreover, EU citizens and their families have the right to live and work anywhere within the EU; citizens of non-EU or non-EEA states may obtain a Blue Card or long-term residency.

A large proportion of immigrants in western European states have come from former eastern bloc states in the 1990s, especially in Spain, Greece, Germany, Italy, Portugal and the United Kingdom. There are frequently specific migration patterns, with geography, language and culture playing a role. For example, there are large numbers of Poles who have moved to the United Kingdom and Ireland and Iceland, while Romanians and also Bulgarians have chosen Spain and Italy. With the earlier of the two recent enlargements of the EU, although most countries restricted free movement by nationals of the acceding countries, the United Kingdom did not restrict for the 2004 enlargement of the European Union and received Polish, Latvian and other citizens of the new EU states. Spain was not restricted for the 2007 enlargement of the European Union and received many Romanians and Bulgarians as well other citizens of the new EU states.

Many of these Polish immigrants to the UK have since returned to Poland, after the serious economic crisis in the UK. Nevertheless, free movement of EU nationals is now an important aspect of migration within the EU, since there are now 27 member states, and has resulted in serious political tensions between Italy and Romania, since Italy has expressed the intention of restricting free movement of EU nationals (contrary to Treaty obligations and the clear jurisprudence of the European Court of Justice).

Another migration trend has been that of Northern Europeans moving toward Southern Europe. Citizens from the European Union make up a growing proportion of immigrants in Spain, coming chiefly from the United Kingdom and Germany, but also from Italy, France, Portugal, The Netherlands, Belgium, etc. British authorities estimate that the population of British citizens living in Spain is much larger than Spanish official figures suggest, establishing them at about 1,000,000, with 800,000 being permanent residents. According to the Financial Times, Spain is the most favoured destination for Western Europeans considering to move from their own country and seek jobs elsewhere in the EU.

Immigration from outside Europe since the 1980s

While most immigrant populations in European countries are dominated by other Europeans, many immigrants and their descendants have ancestral origins outside the continent. For the former colonial powers France, Britain, the Netherlands, Belgium, Spain, and Portugal, most immigrants, and their descendants have ties to former colonies in Africa, the Americas, and Asia. In addition, Germany, Austria, Switzerland, the Netherlands, and Belgium recruited Turkish and Moroccan guest workers beginning in the 1960s, and many current immigrants in those countries today have ties to such recruitment programs.

Moroccan immigrants also began migrating substantially to Spain and Italy for work opportunities in the 1980s. In the Scandinavian countries of Sweden, Denmark, Norway, and Finland, the bulk of non-Western immigrants are refugees and asylum seekers from the Middle East, East Africa, and other regions of the world arriving since the 1980s and 1990s. Increasing globalization has brought a population of students, professionals, and workers from all over the world into major European cities, most notably London, Paris, and Frankfurt. The introduction of the EU Blue Card in May 2009 has further increased the number of skilled professional immigrants from outside of the continent.

Illegal immigration and asylum-seeking in Europe from outside the continent have been occurring since at least the 1990s. While the number of migrants was relatively small for years, it began to rise in 2013. In 2015, the number of asylum seekers arriving from outside Europe increased substantially during the European migrant crisis (see timeline). However, the EU-Turkey deal enacted in March 2016 dramatically reduced this number, and anti-immigrant measures starting in 2017 by the Italian government further cut illegal immigration from the Mediterranean route.

Some scholars claim that the increase in immigration flows from the 1980s is due to global inequalities between poor and rich countries. In 2017, approximately 825,000 persons acquired citizenship of a member state of the European Union, down from 995,000 in 2016. The largest groups were nationals of Morocco, Albania, India, Turkey and Pakistan. 2.4 million non-EU migrants entered the EU in 2017. In addition, cheaper transportation and more advanced technology have further aided migration.

Immigrants in the Nordic countries in 2000–2020

The Nordic countries have differed in their approach to immigration. While Norway and Sweden used to have generous immigration policies, Denmark and Finland had more restricted immigration. Although both Denmark and Finland have experienced a significant increase in their immigrant populations between 2000 and 2020 (6.8% points in Denmark and 5.0% in Finland), Norway (11.9%) and Sweden (11.0%) have seen far greater relative increases.

The table below shows the percentage of the total population in the Nordic countries that are either (1) immigrants or (2) children of two immigrant parents:

| Nr | Country | 2000 | 2010 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2020 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 14.5% | 19.1% | 21.5% | 22.2% | 23.2% | 25.5% | |

| 2 | 6.3% | 11.4% | 15.6% | 16.3% | 16.8% | 18.2% | |

| 3 | 3.2% | 8.9% | 10.0% | 10.8% | 12.0% | 15.6% | |

| 4 | 7.1% | 9.8% | 11.6% | 12.3% | 12.9% | 13.9% | |

| 5 | 2.9% | 4.4% | 6.2% | 6.6% | 7.0% | 7.9% |

Denmark

For decades, Danish immigration and integration policy were built upon the assumption that with the right kind of help, immigrants and their descendants will eventually tend to the same levels of education and employment as Danes. This assumption was proved by a 2019 study by the Danish Immigration Service and the Ministry of Education, while the second generation non-Western immigrants do better than the first generation, the third generation of immigrants with non-Western background do even better education and employment wise than the second generation. One of the reasons was that second-generation immigrants from non-Western countries marry someone from their country of origin and so Danish is not spoken at home which disadvantages children in school. Thereby the process of integration has to start from the beginning for each generation.

Norway

In January 2015 the "immigrant population" in Norway consisted of approximately 805,000 people, including 669,000 foreign-born and 136,000 born in Norway to two immigrant parents. This corresponds to 15.6% of the total population. The cities with the highest share of immigrants are Oslo (32%) and Drammen (27%). The six largest immigrant groups in Norway are Poles, Swedes, Somalis, Lithuanians, Pakistanis and Iraqis.

In the years since 1970, the largest increase in the immigrant population has come from countries in Asia (including Turkey), Africa and South America, increasing from about 3500 in 1970 to about 300,000 in 2011. In the same period, the immigrant population from other Nordic countries and Western Europe has increased modestly from around 42,000 to around 130,000.

Sweden

In 2014 the "immigrant population" in Sweden consisted of approximately 2.09 million people, including 1.60 million foreign-born and 489,000 born in Sweden to two immigrant parents. This corresponds to 21.5% of the total population.

Of the major cities Malmö has the largest immigrant population, estimated to be 41.7% in 2014. However, the smaller municipalities Botkyrka (56.2%), Haparanda (55.5%) and Södertälje (49.4%) all have a higher share of immigrants. In the Swedish capital Stockholm 31.1% (in 2014) of the population are either foreign-born or born in Sweden by two foreign-born parents.

In 2014 127,000 people immigrated to Sweden, while 51,000 left the country. Net immigration was 76,000.

Sweden has been transformed from a nation of emigration ending after World War I to a nation of immigration from World War II onwards. In 2009, Sweden had the fourth largest number of asylum applications in the EU and the largest number per capita after Cyprus and Malta. Immigrants in Sweden are mostly concentrated in the urban areas of Svealand and Götaland and the five largest foreign born populations in Sweden come from Finland, Yugoslavia, Iraq, Poland and Iran.

Finland

Immigration has been a major source of population growth and cultural change throughout much of the history of Finland. The economic, social, and political aspects of immigration have caused controversy regarding ethnicity, economic benefits, jobs for non-immigrants, settlement patterns, impact on upward social mobility, crime, and voting behavior.

At the end of 2017, there were 372,802 foreign born people residing in Finland, which corresponds to 6.8% of the population, while there are 384,123 people with a foreign background, corresponding to 7.0% of the population. Proportionally speaking, Finland has had one of the fastest increases in its foreign-born population between 2000 and 2010 in all of Europe. The majority of immigrants in Finland settle in the Helsinki area, although Tampere, Turku and Kuopio have had their share of immigrants in recent years.

France

As of 2008, the French national institute of statistics (INSEE) estimated that 5.3 million foreign-born immigrants and 6.5 million direct descendants of immigrants (born in France with at least one immigrant parent) lived in France. This represents a total of 11.8 million, or 19% of the population. In terms of origin, about 5.5 million are European, four million Maghrebi, one million Sub-Saharan African, and 400,000 Turkish. Among the 5.3 million foreign-born immigrants, 38% are from Europe, 30% from Maghreb, 12.5% from Sub-Saharan Africa, 14.2% from Asia and 5.3% from America and Oceania. The most significant countries of origin as of 2008 were Algeria (713,000), Morocco (653,000), Portugal (580,000), Italy (317,000), Spain (257,000), Turkey (238,000) and Tunisia (234,000). However, immigration from Asia (especially China, as well as the former French colonies of Vietnam, Cambodia and Laos), and from Sub-Saharan Africa (Senegal, Mali, Nigeria and others), is gaining in importance.

The region with the largest proportion of immigrants is the Île-de-France (Greater Paris), where 40% of immigrants live. Other important regions are Rhône-Alpes (Lyon) and Provence-Alpes-Côte d’Azur (Marseille).

Among the 802,000 newborns in metropolitan France in 2010, 27.3% had at least one foreign-born parent and about one quarter (23.9%) had at least one parent born outside Europe. Including grandparents; almost 40% of newborns in France between 2006 and 2008 had at least one foreign-born grandparent. (11% were born in another European country, 16% in Maghreb, and 12% in another region of the world.)

United Kingdom

In 2014 the number of people who became naturalised British citizens rose to a record 140,795 - a 12% increase from the previous year, and a dramatic increase since 2009. Most new citizens came from Asia (40%) or Africa (32%); the largest three countries of origin were India, Pakistan and Bangladesh with Indians making the largest group. In 2005, an estimated 565,000 migrants arrived to live in the United Kingdom for at least a year, primarily from Asia and Africa, while 380,000 people emigrated from the country for a year or more, chiefly to Australia, Spain and the United States.

In 2014 the net increase was 318,000: immigration was 641,000, up from 526,000 in 2013, while the number of people emigrating (for more than 12 months) was 323,000.

Italy

The total immigrant population of the country is now of 5 million and 73 thousand, about 8.3 percent of the population (2014). However, over 6 million people residing in Italy have an immigration background. Since the expansion of the European Union, the most recent wave of migration has been from surrounding European nations, particularly Eastern Europe, and increasingly Asia, replacing North Africa as the major immigration area. Some 1,200,000 Romanians are officially registered as living in Italy, replacing Albanians (500,000) and Moroccans (520,000) as the largest ethnic minority group. Others immigrants from Central-Eastern Europe are Ukrainians (230,000), Polish (110,000), Moldovans (150,000), Macedonians (100,000), Serbs (110,000), Bulgarians (54,000) Germany (41,000), Bosnians (40,000), Russians (39,600), Croatians (25,000), Slovaks (9,000), Hungarians (8,600). Other major countries of origin are China (300,000), Philippines (180,000), India (150,000), Bangladesh (120,000), Egypt (110,000), Peru (105,000), Tunisia (105,000), Sri Lanka (100.000), Pakistan (100,000), Ecuador (90,000) and Nigeria (80,000). In addition, around 1 million people live in Italy illegally. (As of 2014, the distribution of foreign born population is largely uneven in Italy: 84.9% of immigrants live in the northern and central parts of the country (the most economically developed areas), while only 15.1% live in the southern half of the peninsula.)

Spain

Since 2000, Spain has absorbed around six million immigrants, adding 12% to its population. The total immigrant population of the country now exceeds 5,730,677 (12.2% of the total population). According to residence permit data for 2011, more than 710,000 were Moroccan, another 410,000 were Ecuadorian, 300,000 were Colombian, 230,000 were Bolivian and 150,000 were Chinese; from the EU around 800,000 were Romanian, 370,000 (though estimates place the true figure significantly higher, ranging from 700,000 to more than 1,000,000) were British, 190,000 were German, 170,000 were Italian and 160,000 were Bulgarian. A 2005 regularisation programme increased the legal immigrant population by 700,000 people that year. By world regions, in 2006 there were around 2,300,000 from the EU-27, 1,600,000 from South America, 1,000,000 from Africa, 300,000 from Asia, 200,000 from Central America & Caribbean, 200,000 from the rest of Europe, while 50,000 from North America and 3,000 from the rest of the world.

Portugal

Portugal, long a country of emigration, has now become a country of net immigration, from both its former colonies and other sources. By the end of 2003, legal immigrants represented about 4% of the population, and the largest communities were from Cape Verde, Brazil, Angola, Guinea-Bissau, the United Kingdom, Spain, France, China and Ukraine.

Slovenia

On 1 January 2011 there were almost 229,000 people (11.1%) living in Slovenia with foreign country of birth. At the end of March 2002 when data on the country of birth for total population were for the first and last time collected by a conventional (field) census, the number was almost 170,000 (8.6%). Immigration from abroad, mostly from republics of former Yugoslavia, was the deciding factor for demographic and socioeconomic development of Slovenia in the last fifty years. Also after independence of Slovenia the direction of migration flows between Slovenia and abroad did not change significantly. Migration topics remain closely connected with the territory of former Yugoslavia. Slovenia was and still is the destination country for numerous people from the territory of former Yugoslavia. The share of residents of Slovenia with countries of birth from the territory of former Yugoslavia among all foreign-born residents was 88.9% at the 2002 Census and on 1 January 2011 despite new migration flows from EU Member States and from non-European countries still 86.7%.

Other countries

- Immigration to Austria

- Immigration to Belgium

- Immigration to Bulgaria

- Immigration to Denmark

- Immigration to Germany

- Immigration to Greece

- Immigration to Iceland

- Immigration to the Netherlands

- Immigration to Romania

- Immigration to Switzerland

Opposition

According to a Yougov poll in 2018, majorities in all seven polled countries were opposed to accepting more migrants: Germany (72%), Denmark (65%), Finland (64%), Sweden (60%), United Kingdom (58%), France (58%) and Norway (52%).

A February 2017 poll of 10 000 people in 10 European countries by Chatham House found on average a majority (55%) were opposed to further Muslim immigration, with opposition especially pronounced in a number of countries: Austria (65%), Poland (71%), Hungary (64%), France (61%) and Belgium (64%). Except for Poland, all of those had recently suffered jihadist terror attacks or been at the centre of a refugee crisis. Of those opposed to further Muslim immigration, 3/4 classify themselves as on the right of the political spectrum. Of those self-classifying as on the left of the political spectrum, 1/3 supported a halt.

Denmark

In Denmark, the parliamentary party most strongly associated with anti-immigration policies is the Danish People's Party.

According to a Gallup poll in 2017, two out of three (64%) wished for limiting immigration from Muslim countries which was an increase from 2015 (54%).

According to a 2018 Yougov poll, 65% of Danes opposed accepting more migrants into the country.

On August 14, 2020, the Ministry of Immigration and Integration in Denmark revealed that it denied 83 people Danish citizenship in the past two years because they have committed serious crimes.

Finland

According to a 2018 Yougov poll, 64% of Finns opposed accepting more migrants into the country.

France

In France, the National Front seeks to limit immigration. Major media, political parties, and a large share of the public believe that anti-immigration sentiment has increased since the country's riots of 2005.

According to a 2018 Yougov poll, 58% of the French opposed accepting more migrants into the country.

Germany

In Germany, the National Democratic Party and the Alternative for Germany oppose immigration.

In 2018, a poll by Pew Research found that a majority (58%) wanted fewer immigrants to be allowed into the country, 30% wanted to keep the current level and 10% wanted to increase immigration.

According to a 2018 Yougov poll, 72% of Germans opposed accepting more migrants into the country.

Greece

In February 2020, more than 10 000 individuals attempted to cross the border between Greece and Turkey after Turkish president Recep Tayyip Erdoğan opened its border to Europe, but they were blocked by Greek army and police forces. Hundreds of Greek soldiers and armed police resisted the trespassers and fired tear gas at them. Among those who attempted to cross were individuals from Africa, Iran and Afghanistan. Greece responded by refusing to accept asylum applications for a month.

In March 2020, migrants set fires and threw Molotov cocktail firebombs over to the Greek side in order to break down the border fence. Greek and European forces responded with tear gas and by trying to keep the fence intact. By 11 March, 348 people had been arrested and 44,353 cases of unlawful entry had been prevented.

Italy

Public anti-immigrant discourse started in Italy in 1985 by the Bettino Craxi government, which in a public speech drew a direct link between the high number of clandestine immigrants and some terrorist incidents. Public discourse by the media hold that the phenomenon of immigration is uncontrollable and of undefined proportions.

According to poll published by Corriere della Sera, one of two respondents (51%) approved closing Italy's ports to further boat migrants arriving via the Mediterranean, while 19% welcomed further boat migrants.

In 2018, a poll by Pew Research found that a majority (71%) wanted fewer immigrants to be allowed into the country, 18% wanted to keep the current level and 5% wanted to increase immigration.

Norway

In Norway, the only parliamentary party that seeks to limit immigration is the Progress Party. Minor Norwegian parties seeking to limit immigration are the Democrats in Norway, the Christian Unity Party, the Pensioners' Party and the Coastal Party.

According to a 2018 Yougov poll, 52% of Norwegians opposed accepting more migrants into the country.

Poland

A 2015 opinion poll conducted by the Centre for Public Opinion Research (CBOS) found that 14% thought that Poland should let asylum-seekers enter and settle in Poland, 58% thought Poland should let asylum-seekers stay in Poland until they can return to their home country, and 21% thought Poland should not accept asylum-seekers at all. Furthermore, 53% thought Poland should not accept asylum-seekers from the Middle East and North Africa, with only 33% thinking Poland should accept them.

Another opinion poll conducted by the same organisation found that 86% of Poles think that Poland does not need more immigrants, with only 7% thinking Poland needs more immigrants.

Despite above in year 2017, 683 000 immigrants from outside of EU arrived to Poland. 87.4% out of them immigrated for work. "Among the EU Member States, Poland issued the highest number (683 thousand) of first residence permits in 2017, followed by Germany (535 thousand) and the United Kingdom (517 thousand)."

Sweden

In response to the high immigration of 2015, the anti-immigration party Sweden Democrats rose to 19.9% in the Statistics Sweden poll.

In late 2015, Sweden introduced temporary border checks on the Øresund Bridge between Denmark and Sweden and public transport operators were instructed to only let people with residence in Sweden board trains or buses. The measures reduced the number of asylum seekers from 163 000 in 2015 to 29 000 in 2016.

In 2018, a poll by Pew Research found that a small majority (52%) wanted fewer immigrants to be allowed into the country, 33% wanted to keep the current level and 14% wanted to increase immigration.

According to a 2018 Yougov poll, 60% of Swedes opposed accepting more migrants into the country.

In February 2020 finance minister Magdalena Andersson encouraged migrants to head for other countries than Sweden. Andersson stated in an interview that integration of immigrants in Sweden wasn't working since neither before nor after 2015 and that Sweden cannot accept more immigration than it is able to integrate.

Switzerland

During the 1990s under Christoph Blocher, the Swiss People's Party started to develop an increasingly eurosceptic and anti-immigration agenda. In 2014, they launched a popular initiative titled "Against mass immigration" that was narrowly accepted. They are currently the largest party in the National Council with 53 seats.

United Kingdom

Anti-immigration sentiment in the United Kingdom has historically focused on non-indigenous African, Afro-Caribbean and especially South Asian migrants, all of whom began to arrive from the Commonwealth of Nations in greater numbers following World War II. Since the fall of the Soviet Union and the enlargement of the European Union, the increased movement of people out of countries such as Poland, Romania and Lithuania has shifted much of this attention towards migrants from Eastern Europe. While working-class migrants tend to be the focus of anti-immigration sentiment, there is also some discontent about Russian, Chinese, Singaporean and Gulf Arab multimillionaires resident in the UK, particularly in London and South East England. These residents often invest in property and business, and are perceived as living extravagant "jet-set" lifestyles marked by conspicuous consumption while simultaneously taking advantage of tax loopholes connected to non-dom status.

Policies of reduced immigration, particularly from the European Union, are central to the manifestos of parties such as the UK Independence Party. Such policies have also been discussed by some members of the largest parties in Parliament, most significantly the Conservatives.

Statistics

By host country

Statistics for European Union 27 (post-Brexit)

| Country | Refused entry | illegally present | Order to leave | Returned outside the EU |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EU 27 (2018) | 454600 | 456700 | 145900 | |

| EU 27 (2019) | 717600 | 627900 | 491200 | 142300 |

| 2018-2019 change (%) | +58% | +10% | +8% | -2.5% |

2013 UN data

This is a list of European countries by immigrant population, based on the United Nations report Trends in International Migrant Stock: The 2013 Revision.

| Country | Number of immigrants | Percentage of total number of immigrants in the world |

Immigrants as percentage of national population |

|---|---|---|---|

| 11,048,064 | 4.8 | 7.7 | |

| 9,845,244 | 4.3 | 11.9 | |

| 7,824,131 | 3.4 | 12.4 | |

| 7,439,086 | 3.2 | 11.6 | |

| 5,891,208 | 2.8 | 9.6 (2016) | |

| 5,721,457 | 2.5 | 9.4 | |

| 5,151,378 | 2.2 | 11.4 | |

| 2,335,059 | 1.0 | 28.9 | |

| 1,964,922 | 0.9 | 11.7 | |

| 1,864,889 | 0.8 | 2.5 | |

| 1,130,025 | 0.7 | 15.9 | |

| 1,333,807 | 0.6 | 15.7 | |

| 1,159,801 | 0.5 | 10.4 | |

| 1,085,396 | 0.5 | 11.6 | |

| 988,245 | 0.4 | 8.9 | |

| 893,847 | 0.4 | 8.4 | |

| 756,980 | 0.3 | 17.6 | |

| 735,535 | 0.3 | 15.9 | |

| 694,508 | 0.3 | 13.8 | |

| 663,755 | 0.3 | 0.9 | |

| 556,825 | 0.3 | 9.9 | |

| 532,457 | 0.3 | 5.6 | |

| 449,632 | 0.3 | 4.7 | |

| 446,434 | 0.3 | 8.1 | |

| 439,116 | 0.2 | 4.0 | |

| 391,508 | 0.2 | 11.2 | |

| 323,843 | 0.2 | 3.4 | |

| 317,001 | 0.2 | 10.6 | |

| 282,887 | 0.2 | 13.8 | |

| 233,293 | 0.2 | 11.3 | |

| 229,409 | 0.1 | 43.3 | |

| 209,984 | 0.1 | 16.4 | |

| 207,313 | 0.1 | 18.2 | |

| 198,839 | 0.1 | 0.9 | |

| 189,893 | 0.1 | 4.4 | |

| 147,781 | 0.1 | 4.9 | |

| 139,751 | 0.1 | 6.6 | |

| 96,798 | 0.1 | 3.1 | |

| 84,101 | 0.1 | 1.2 | |

| 45,086 | 0.1 | 56.9 | |

| 44,688 | 0.1 | 52.0 | |

| 34,377 | 0.1 | 10.7 | |

| 24,299 | 0.1 | 64.2 | |

| 23,197 | 0.1 | 0.6 | |

| 12,208 | 0.1 | 33.1 | |

| 9,662 | 0.1 | 33.0 | |

| 4,399 | 0.1 | 15.4 | |

| 799 | 0.1 | 100.0 |

2010 data for European Union 28

In 2010, 47.3 million people lived in the EU, who were born outside their resident country. This corresponds to 9.4% of the total EU population. Of these, 31.4 million (6.3%) were born outside the EU and 16.0 million (3.2%) were born in another EU member state. The largest absolute numbers of people born outside the EU were in Germany (6.4 million), France (5.1 million), the United Kingdom (4.7 million), Spain (4.1 million), Italy (3.2 million), and The Netherlands (1.4 million).

| State | Total population (millions) | Total Foreign-born (millions) | % | Born in other EU state (millions) | % | Born in a non-EU state (millions) | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 81.802 | 9.812 | 12.0 | 3.396 | 4.2 | 6.415 | 7.8 | |

| 64.716 | 7.196 | 11.1 | 2.118 | 3.3 | 5.078 | 7.8 | |

| 62.008 | 7.012 | 11.3 | 2.245 | 3.6 | 4.767 | 7.7 | |

| 46.000 | 6.422 | 14.0 | 2.328 | 5.1 | 4.094 | 8.9 | |

| 61.000 | 4.798 | 8.5 | 1.592 | 2.6 | 3.205 | 5.3 | |

| 16.575 | 1.832 | 11.1 | 0.428 | 2.6 | 1.404 | 8.5 | |

| 11.305 | 0.960 | 9.6 | 0.320 | 2.3 | 0.640 | 6.3 | |

| 3.758 | 0.766 | 20.0 | 0.555 | 14.8 | 0.211 | 5.6 | |

| 9.340 | 1.337 | 14.3 | 0.477 | 5.1 | 0.859 | 9.2 | |

| 8.367 | 1.276 | 15.2 | 0.512 | 6.1 | 0.764 | 9.1 | |

| 10.666 | 1.380 | 12.9 | 0.695 | 6.5 | 0.685 | 6.4 | |

| 10.637 | 0.793 | 7.5 | 0.191 | 1.8 | 0.602 | 5.7 | |

| 5.534 | 0.500 | 9.0 | 0.152 | 2.8 | 0.348 | 6.3 | |

| 2.050 | 0.228 | 11.1 | 0.021 | 1.8 | 0.207 | 9.3 | |

| EU 28 | 501.098 | 47.348 | 9.4 | 15.980 | 3.2 | 31.368 | 6.3 |

2005 UN data

According to the United Nations report World Population Policies 2005, European countries that have the highest net foreign populations are:

| Country | Population | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 12,080,000 | 8.5 |

| |

| 10,144,000 | 12.3 |

| |

| 6,833,000 | 14.7 |

| |

| 6,471,000 | 10.2 |

| |

| 5,408,000 | 9 |

| |

| 5,000,000 | 8.2 |

| |

| 4,790,000 | 10.8 |

| |

| 1,660,000 | 23 |

| |

| 1,638,000 | 10 |

| |

| 1,234,000 | 15 |

|

The European countries with the highest proportion or percentage of non-native residents are small nations or microstates. Andorra is the country in Europe with the highest percentage of immigrants, 77% of the country's 82,000 inhabitants. Monaco is the second with the highest percentage of immigrants, they make up 70% of the total population of 32,000; and Luxembourg is the third, immigrants are 37% of the total of 480,000; in Liechtenstein they are 35% of the 34,000 people; and in San Marino they comprise 32% of the country's population of 29,000.

Countries in which immigrants form between 25% and 10% of the population are: Switzerland (23%), Latvia (19%), Estonia (15%), Austria (15%), Croatia (15%), Ukraine (14.7%), Cyprus (14.3%), Ireland (14%), Moldova (13%), Germany (12.3%), Sweden (12.3%), Belarus (12%), Slovenia (11.1%), Spain (10.8%, 12.2% in 2010), France (10.2%), and the Netherlands (10%).[116] The United Kingdom (9%), Greece (8.6%), Russia (8.5%), Finland (8.1%), Iceland (7.6%), Norway (7.4%), Portugal (7.2%), Denmark (7.1%), Belgium (6.9%) and the Czech Republic (6.7%), each have a proportion of immigrants between 10% and 5% of the total population.

2006 data

Eurostat data reported in 2006 that some EU member states as receiving "large-scale" immigration. The EU in 2005 had an overall net gain from international migration of 1.8 million people, which accounted for almost 85% of Europe's total population growth that year. In 2004, a total of 140,033 people immigrated to France. Of them, 90,250 were from Africa and 13,710 from elsewhere in Europe. In 2005, the total number of immigrants fell slightly, to 135,890.

By origin

In 2019

In the European union, in 2019, 706 400 persons acquired citizenship, the main nation of origin for citizenship grant were by decreasing number: Morocco, Albania, the United Kingdom, Syria and Turkey.

the largest groups were Moroccans (66 800, or 9.5 %), followed by Albanians (41 700, or 5.9 %), Britons (29 800, or 4.2 %), Syrian (29 100, or 4.1 %) and Turks (28 600, or 4.0 %). The majority of Moroccans acquired citizenship of Spain (37 %), Italy (24 %) or France (24 %), while the majority of Albanians received Italian citizenship (62 %). Almost half of the Britons received German citizenship (46 %) and more than half of the Syrians received Swedish citizenship (69 %). The majority of Turks acquired German citizenship (57 %)

— eurostat

Previous years

This is a breakdown by major area of origin of the 72.4 million migrants residing in Europe (out of a population of 742 million) at mid-2013, based on the United Nations report Trends in International Migrant Stock: The 2013 Revision.

| Area of origin | Number of immigrants to Europe (millions) |

Percentage of total number of immigrants to Europe |

|---|---|---|

| Africa | 8.9 | 12 |

| Asia | 18.6 | 27 |

| Europe | 37.8 | 52 |

| Latin America and the Caribbean | 4.5 | 6 |

| Northern America | 0.9 | 1 |

| Oceania | 0.3 | 0.4 |

| Various | 1.3 | 2 |

| TOTAL | 72.4 | 100 |

Approximate populations of non-European origin in Europe (about 20 - 30+ millions, or 3 - 4% (depending on the definition of non-European origin), out of a total population of approx. 831 million):

- Black Africans (including Afro-Caribbeans and others by descent): approx. 9 to 10 million in the European Union and around 12.5 in Europe as a whole. Between 4 and 5 million Sub-Saharan and Afro-Caribbeans live in France but also 2.5 million in the United Kingdom, Italy, Germany, Spain, Belgium, the Netherlands and Portugal. (in Spain and Portugal Afro-Caribbean and Afro-Latin American are included in Latin Americans)

- Turks (including Turks from Turkey and Northern Cyprus): approx. 9 million (this estimate does not include the 10 million Turks within the European portion of Turkey); of whom 3 to over 7 million in Germany but also the rest in France and the Netherlands with over 2 million Turks in France and Turks in the Netherlands, Austria, the United Kingdom, Belgium, Sweden, Switzerland, Denmark, Italy, Bulgaria, Macedonia, Greece, Romania, Finland, Serbia and Norway. (see Turks in Europe)

- Arabs (including North African and Middle Eastern Arabs): approx. 6 to 7 million Arabs live in France but also Spain with 1.6 to 1.8 million Arabs, 1.2 million Arabs in Germany, the United Kingdom, Italy, Greece, Sweden, the Netherlands, Denmark, Belgium, Norway, Switzerland, Finland and Russia. (see Arabs in Europe) Many Arabs in Europe are Lebanese and Syrian.

- Indians: approx. 2.5 million; 1.9 million mostly in the United Kingdom but also 473,520 in France including the overseas territories, 240,000 in the Netherlands, 203,052 in Italy, 185,085 in Germany, Ireland and Portugal.

- Pakistanis: approx. 1.1 million in the United Kingdom, but also 120,000 in France, 118,181 in Italy, Spain, and Norway.

- Bengali: approx. 600,000 mostly in United Kingdom, but also 85,000 in Italy, 35,000 in France, Spain, Sweden, Finland and Greece.

- Latin Americans (includes Afro-Latin Americans, Afro-Caribbeans, Native Americans, White Latin Americans, miscegenation, etc.): approx. 5.0 million; mostly in Spain (c. 2.9 million) but also 1.3 million in France, 354,180 in Italy, +100,000 in Portugal, 245,000 in the United Kingdom and some in Germany.

- Armenians: approx. 2 million; mostly in Russia but also 800,000 in France, Ukraine, Greece, Bulgaria, Spain, Germany, Poland, the United Kingdom and Belgium.

- Berbers: approx. 2 million live in France but also Italy, the Netherlands, Belgium and Spain.

- Kurds: approx. 2 million; mostly in Germany, France, Sweden, Russia, the Netherlands, Belgium and the United Kingdom.

- Chinese: approx. 1 million; 600,000-700,000 of them live in France, 433,000 live in the United Kingdom, Russia, Italy, Spain, Germany and the Netherlands.

- Vietnamese: approx. 800,000; mostly in France, Germany, the United Kingdom, Poland, Norway, the Netherlands, Finland, Sweden, Denmark and Russia.

- Filipinos: approx. 600,000; mostly in the United Kingdom, France, Italy, Spain, Germany, the Netherlands, Sweden, Austria and Ireland.

- Iranians: approx. 250,000; mostly in Germany, Sweden, the United Kingdom, Russia, the Netherlands, France, Austria, Norway, Spain and Denmark.

- Somalis: approx. 200,000; mostly in the United Kingdom, Sweden, the Netherlands, Norway, Germany, Finland, Denmark and Italy.

- Assyrians/Chaldeans/Syriacs: approx. 200,000; mostly in Sweden, Germany, Russia, France and The Netherlands.

Irregular border crossings

The EU Border and Coast Guard Agency (Frontex) uses the terms "illegal" and "irregular" border crossings for crossings of an EU external border but not at an official border-crossing point. These include people rescued at sea. Because many migrants cross more than one external EU border (for instance when traveling through the Balkans from Greece to Hungary), the total number of irregular EU external border crossings is often higher than the number of irregular migrants arriving in the EU in a year. News media sometimes misrepresent these figures as given by Frontex.

Frontex tracks and publishes data on numbers of crossings along the main six routes twice a year. The following table summarises the number of "irregular crossings" of the European Union's various external borders. Note that the figures do not add up to the total number of people coming into the EU illegally in a given year, since many migrants are counted twice (for instance, once when entering Greece and a second time upon entering Hungary).

Studies

Gallup has published a study estimating potential migrants in 2010. The study estimated that 700 million adults worldwide would prefer to migrate to another country. Potential migrants were asked for their country of preference if they were given free choice.

The total number of potential migrants to the European Union is estimated at 200 million, comparable to the number for North America (USA and Canada). In addition, an estimated 40 million potential migrants within the EU desire to move to another country within the EU, giving the EU the highest intra-regional potential migration rate.

The study estimates that from 2015 to 2017, there were about 750 million potential migrants. One in five potential migrants (21%), or about 158 million adults worldwide name the U.S. as their desired future residence. Canada, Germany, France, Australia and the United Kingdom each appeal to more than 30 million adults. Apart from the United States, the top desired target countries were:Canada (47 million), Germany (42 million), France (36 million), Australia (36 million) and the United Kingdom (34 million).

The study also compared the number of potential migrants to their desired destination's population, resulting in a Net Migration Index expressing potential population growth. This list is headed by Singapore, which would experience population growth by +219%. Among European countries, Switzerland would experience the highest growth, by +150%, followed by Sweden (+78%), Spain (+74%), Ireland (+66%), the United Kingdom (+62%) and France (+60%). The European countries with highest potential population loss are Kosovo and North Macedonia, with -28% each.