The economic history of the United States is about characteristics of and important developments in the economy of the U.S., from the colonial era to the present. The emphasis is on productivity and economic performance and how the economy was affected by new technologies, the change of size in economic sectors and the effects of legislation and government policy.

Colonial economy

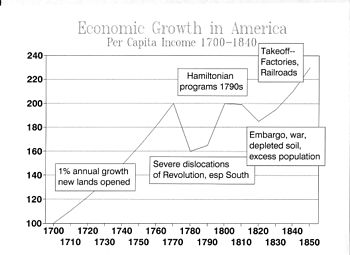

The colonial economy was characterized by an abundance of land and natural resources and a severe scarcity of labor. This was the opposite of Europe and attracted immigrants despite the high death rate caused by New World diseases. From 1700 to 1774, the output of the thirteen colonies increased 12-fold, giving the colonies an economy about 30% the size of Britain's at the time of independence.

Population growth was responsible for over three-quarters of the economic growth of the British American colonies. The free white population had the highest standard of living in the world. There was very little change in productivity and little in the way of introduction of new goods and services. Under the mercantilist system, Britain put restrictions on the products that could be made in the colonies and put restrictions on trade outside the British Empire. The colonial economy differed significantly from that of most other regions in that land and natural resources were abundant in America but labor was scarce.

Demographics

Initial colonization of North America was extremely difficult and most settlers before 1625 died in their first year. Settlers had to depend on what they could hunt and gather, what they brought with them, and uncertain shipments of food, tools, and supplies until they could build shelters and forts, clear land, and grow enough food, as well as build gristmills, sawmills, ironworks, and blacksmith shops to be self-supporting. They also had to defend themselves against raids from Native Americans. After 1629 population growth was very rapid due to high birth rates (8 children per family versus 4 in Europe) and lower death rates than in Europe, in addition to immigration. The long life expectancy of the colonists was due to the abundant supplies of food and firewood and the low population density that limited the spread of infectious diseases. The death rate from diseases, especially malaria, was higher in the warm, humid Southern Colonies than in the cold New England Colonies.

The higher birth rate was due to better employment opportunities. Many young adults in Europe delayed marriage for financial reasons, and many servants in Europe were not permitted to marry. The population of white settlers grew from an estimated 40,000 in 1650 to 235,000 in 1700. In 1690, there were an estimated 13,000 black slaves. The population grew at an annual rate of over 3% throughout the 18th century, doubling every 25 years or less. By 1775 the population had grown to 2.6 million, of which 2.1 million were white, 540,000 black and 50,000 Native American, giving the colonies about one-third of the population of Britain. The three most populated colonies in 1775 were Virginia, with a 21% share, and Pennsylvania and Massachusetts with 11% each.

The economy

The colonial economy of what would become the United States was pre-industrial, primarily characterized by subsistence farming. Farm households also were engaged in handicraft production, mostly for home consumption, but with some goods sold, mainly gold.

The market economy was based on extracting and processing natural resources and agricultural products for local consumption, such as mining, gristmills and sawmills, and the export of agricultural products. The most important agricultural exports were raw and processed feed grains (wheat, Indian corn, rice, bread and flour) and tobacco. Tobacco was a major crop in the Chesapeake Colonies and rice a major crop in South Carolina. Dried and salted fish was also a significant export. North Carolina was the leading producer of naval stores, which included turpentine (used for lamps), rosin (candles and soap), tar (rope and wood preservative) and pitch (ships' hulls). Another export was potash, which was derived from hardwood ashes and was used as a fertilizer and for making soap and glass.

The colonies depended on Britain for many finished goods, partly because laws such as the Navigation Acts of 1660 prohibited making many types of finished goods in the colonies. These laws achieved the intended purpose of creating a trade surplus for Britain. The colonial balance of trade in goods heavily favored Britain; however, American shippers offset roughly half of the goods trade deficit with revenues earned by shipping between ports within the British Empire.

The largest non-agricultural segment was ship building, which was from 5 to 20% of total employment. About 45% of American made ships were sold to foreigners.

Exports and related services accounted for about one-sixth of income in the decade before revolution. Just before the revolution, tobacco was about a quarter of the value of exports. Also at the time of the revolution the colonies produced about 15% of world iron, although the value of exported iron was small compared to grains and tobacco. The mined American iron ores at that time were not large deposits and were not all of high quality; however, the huge forests provided adequate wood for making charcoal. Wood in Britain was becoming scarce and coke was beginning to be substituted for charcoal; however, coke made inferior iron. Britain encouraged colonial production of pig and bar iron, but banned construction of new colonial iron fabrication shops in 1750; however, the ban was mostly ignored by the colonists.

Settlement was sparse during the colonial period and transportation was severely limited by lack of improved roads. Towns were located on or near the coasts or navigable inland waterways. Even on improved roads, which were rare during the colonial period, wagon transport was very expensive. Economical distance for transporting low value agricultural commodities to navigable waterways varied but was limited to something on the order of less than 25 miles. In the few small cities and among the larger plantations of South Carolina, and Virginia, some necessities and virtually all luxuries were imported in return for tobacco, rice, and indigo exports.

By the 18th century, regional patterns of development had become clear: the New England colonies relied on shipbuilding and sailing to generate wealth; plantations (many using slave labor) in Maryland, Virginia, and the Carolinas grew tobacco, rice, and indigo; and the middle colonies of New York, Pennsylvania, New Jersey, and Delaware shipped general crops and furs. Except for slaves, standards of living were even higher than in England itself.

New England

The New England region's economy grew steadily over the entire colonial era, despite the lack of a staple crop that could be exported. All the provinces and many towns as well, tried to foster economic growth by subsidizing projects that improved the infrastructure, such as roads, bridges, inns and ferries. They gave bounties and subsidies or monopolies to sawmills, grist mills, iron mills, pulling mills (which treated cloth), salt works and glassworks. Most importantly, colonial legislatures set up a legal system that was conducive to business enterprise by resolving disputes, enforcing contracts, and protecting property rights. Hard work and entrepreneurship characterized the region, as the Puritans and Yankees endorsed the "Protestant Ethic", which enjoined men to work hard as part of their divine calling.

The benefits of growth were widely distributed in New England, reaching from merchants to farmers to hired laborers. The rapidly growing population led to shortages of good farm land on which young families could establish themselves; one result was to delay marriage, and another was to move to new lands farther west. In the towns and cities, there was strong entrepreneurship, and a steady increase in the specialization of labor. Wages for men went up steadily before 1775; new occupations were opening for women, including weaving, teaching, and tailoring. The region bordered New France, and in the numerous wars the British poured money in to purchase supplies, build roads and pay colonial soldiers. The coastal ports began to specialize in fishing, international trade and shipbuilding—and after 1780 in whaling. Combined with growing urban markets for farm products, these factors allowed the economy to flourish despite the lack of technological innovation.

The Connecticut economy began with subsistence farming in the 17th century, and developed with greater diversity and an increased focus on production for distant markets, especially the British colonies in the Caribbean. The American Revolution cut off imports from Britain, and stimulated a manufacturing sector that made heavy use of the entrepreneurship and mechanical skills of the people. In the second half of the 18th century, difficulties arose from the shortage of good farmland, periodic money problems, and downward price pressures in the export market. The colonial government from time to time attempted to promote various commodities such as hemp, potash, and lumber as export items to bolster its economy and improve its balance of trade with Great Britain.

Urban centers

Historian Carl Bridenbaugh examined in depth five key cities: Boston (population 16,000 in 1760), Newport Rhode Island (population 7500), New York City (population 18,000), Philadelphia (population 23,000), and Charles Town (Charlestown, South Carolina), (population 8000). He argues they grew from small villages to take major leadership roles in promoting trade, land speculation, immigration, and prosperity, and in disseminating the ideas of the Enlightenment, and new methods in medicine and technology. Furthermore, they sponsored a consumer taste for English amenities, developed a distinctly American educational system, and began systems for care of people in need.

On the eve of the Revolution, 95 percent of the American population lived outside the cities—much to the frustration of the British, who captured the cities with their Royal Navy, but lacked the manpower to occupy and subdue the countryside. In explaining the importance of the cities in shaping the American Revolution, Benjamin Carp compares the important role of waterfront workers, taverns, churches, kinship networks, and local politics. Historian Gary B. Nash emphasizes the role of the working class, and their distrust of their social superiors in northern ports. He argues that working class artisans and skilled craftsmen made up a radical element in Philadelphia that took control of the city starting about 1770 and promoted a radical Democratic form of government during the revolution. They held power for a while, and used their control of the local militia to disseminate their ideology to the working class, and to stay in power until the businessmen staged a conservative counterrevolution.

Political environment

Mercantilism: old and new

The colonial economies of the world operated under the economic philosophy of mercantilism, a policy by which countries attempted to run a trade surplus, with their own colonies or other countries, to accumulate gold reserves. Colonies were used as suppliers of raw materials and as markets for manufactured goods while being prohibited from engaging in most types of manufacturing. The colonial powers of England, France, Spain and the Dutch Republic tried to protect their investments in colonial ventures by limiting trade between each other's colonies.

The Spanish Empire clung to old style mercantilism, primarily concerned with enriching the Spanish government by accumulating gold and silver, mainly from mines in their colonies. The Dutch and particularly the British approach was more conducive to private business.

The Navigation Acts, passed by the British Parliament between 1651 and 1673, affected the British American colonies.

Important features of the Navigation Acts included:

- Foreign vessels were excluded from carrying trade between ports within the British Empire

- Manufactured goods from Europe to the colonies had to pass through England

- Enumerated items, which included furs, ship masts, rice, indigo and tobacco, were only allowed to be exported to Great Britain.

Although the Navigation Acts were enforced, they had a negligible effect on commerce and profitability of trade. In 1770 illegal exports and smuggling to the West Indies and Europe were about equal to exports to Britain.

On the eve of independence Britain was in the early stage of the Industrial Revolution, with cottage industries and workshops providing finished goods for export to the colonies. At that time, half of the wrought iron, beaver hats, cordage, nails, linen, silk, and printed cotton produced in Britain were consumed by the British American colonies.

Free enterprise

The domestic economy of the British American colonies enjoyed a great deal of freedom, although some of their freedom was due to lack of enforcement of British regulations on commerce and industry. Adam Smith used the colonies as an example of the benefits of free enterprise. Colonists paid minimal taxes.

Some colonies, such as Virginia, were founded principally as business ventures. England's success at establishing settlements on the North American coastline was due in large part to its use of charter companies. Charter companies were groups of stockholders (usually merchants and wealthy landowners) who sought personal economic gain and, perhaps, wanted also to advance England's national goals. While the private sector financed the companies, the king also provided each project with a charter or grant conferring economic rights as well as political and judicial authority. The colonies did not show profits, however, and the disappointed English investors often turned over their colonial charters to the settlers. The political implications, although not realized at the time, were enormous. The colonists were left to build their own governments and their own economy.

Taxation

The colonial governments had few expenses and taxes were minimal.

Although the colonies provided an export market for finished goods made in Britain or sourced by British merchants and shipped from Britain, the British incurred the expenses of providing protection against piracy by the British Navy and other military expenses. An early tax became known as the Molasses Act of 1733.

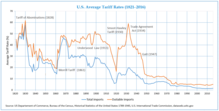

In the 1760s the London government raised small sums by new taxes on the colonies. This occasioned an enormous uproar, from which historians date the origins of the American Revolution. The issue was not the amount of the taxes—they were quite small—but rather the constitutional authority of Parliament versus the colonial assemblies to vote taxes. New taxes included the Sugar Act of 1764, the Stamp Act of 1765 and taxes on tea and other colonial imports. Historians have debated back and forth about the cost imposed by the Navigation Acts, which were less visible and rarely complained about. However, by 1795, the consensus view among economic historians and economists was that the "costs imposed on [American] colonists by the trade restrictions of the Navigation Acts were small."

The American Revolution

Americans in the Thirteen Colonies demanded their rights as Englishmen, as they saw it, to select their own representatives to govern and tax themselves – which Britain refused. The Americans attempted resistance through boycotts of British manufactured items, but the British responded with a rejection of American rights and the Intolerable Acts of 1774. In turn, the Americans launched the American Revolution, resulting in an all-out war against the British and independence for the new United States of America. The British tried to weaken the American economy with a blockade of all ports, but with 90% of the people in farming, and only 10% in cities, the American economy proved resilient and able to support a sustained war, which lasted from 1775 to 1783.

The American Revolution (1775–1783) brought a dedication to unalienable rights to "life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness", which emphasize individual liberty and economic entrepreneurship, and simultaneously a commitment to the political values of liberalism and republicanism, which emphasize natural rights, equality under the law for all citizens, civic virtue and duty, and promotion of the general welfare.

Britain's war against the Americans, French and Spanish cost about £100 million. The Treasury borrowed 40% of the money it needed and raised the rest through an efficient system of taxation. Heavy spending brought France to the verge of bankruptcy and revolution.

Congress and the American states had no end of difficulty financing the war. In 1775 there was at most 12 million dollars in gold in the colonies, not nearly enough to cover existing transactions, let alone on a major war. The British government made the situation much worse by imposing a tight blockade on every American port, which cut off almost all imports and exports. One partial solution was to rely on volunteer support from militiamen, and donations from patriotic citizens. Another was to delay actual payments, pay soldiers and suppliers in depreciated currency, and promise it would be made good after the war. Indeed, in 1783 the soldiers and officers were given land grants to cover the wages they had earned but had not been paid during the war. Not until 1781, when Robert Morris was named Superintendent of Finance of the United States, did the national government have a strong leader in financial matters. Morris used a French loan in 1782 to set up the private Bank of North America to finance the war. Seeking greater efficiency, Morris reduced the civil list, saved money by using competitive bidding for contracts, tightened accounting procedures, and demanded the federal government's full share of money and supplies from the states.

The Second Continental Congress used four main methods to cover the cost of the war, which cost about 66 million dollars in specie (gold and silver). Congress made two issues of paper money, in 1775–1780, and in 1780–81. The first issue amounted to 242 million dollars. This paper money would supposedly be redeemed for state taxes, but the holders were eventually paid off in 1791 at the rate of one cent on the dollar. By 1780, the paper money was "not worth a Continental", as people said, and a second issue of new currency was attempted. The second issue quickly became nearly worthless—but it was redeemed by the new federal government in 1791 at 100 cents on the dollar. At the same time the states, especially Virginia and the Carolinas, issued over 200 million dollars of their own currency. In effect, the paper money was a hidden tax on the people, and indeed was the only method of taxation that was possible at the time. The skyrocketing inflation was a hardship on the few people who had fixed incomes—but 90 percent of the people were farmers, and were not directly affected by that inflation. Debtors benefited by paying off their debts with depreciated paper. The greatest burden was borne by the soldiers of the Continental Army, whose wages—usually in arrears—declined in value every month, weakening their morale and adding to the hardships suffered by their families.

Starting in 1776, the Congress sought to raise money by loans from wealthy individuals, promising to redeem the bonds after the war. The bonds were in fact redeemed in 1791 at face value, but the scheme raised little money because Americans had little specie, and many of the rich merchants were supporters of the Crown. Starting in 1776, the French secretly supplied the Americans with money, gunpowder and munitions in order to weaken its arch enemy, Great Britain. When the Kingdom of France officially entered the war in 1778, the subsidies continued, and the French government, as well as bankers in Paris and Amsterdam loaned large sums to the American war effort. These loans were repaid in full in the 1790s.

Beginning in 1777, Congress repeatedly asked the states to provide money. But the states had no system of taxation either, and were little help. By 1780 Congress was making requisitions for specific supplies of corn, beef, pork and other necessities—an inefficient system that kept the army barely alive.

The cities played a major role in fomenting the American Revolution, but they were hard hit during the war itself, 1775–83. They lost their main role as oceanic ports, because of the blockade by the Royal Navy. Furthermore, the British occupied the cities, especially New York 1776–83, and the others for briefer periods. During the occupations they were cut off from their hinterland trade and from overland communication. When the British finally departed in 1783, they took out large numbers of wealthy merchants who resumed their business activities elsewhere in the British Empire.

Confederation: 1781–1789

A brief economic recession followed the war, but prosperity returned by 1786. About 60,000 to 80,000 American Loyalists left the U.S. for elsewhere in the British Empire, especially Canada. They took their slaves but left lands and properties behind. Some returned in the mid-1780s, especially to more welcoming states like New York and South Carolina. Economically mid-Atlantic states recovered particularly quickly and began manufacturing and processing goods, while New England and the South experienced more uneven recoveries. Trade with Britain resumed, and the volume of British imports after the war matched the volume from before the war, but exports fell precipitously.

John Adams, serving as the minister to Britain, called for a retaliatory tariff in order to force the British to negotiate a commercial treaty, particularly regarding access to Caribbean markets. However, Congress lacked the power to regulate foreign commerce or compel the states to follow a unified trade policy, and Britain proved unwilling to negotiate. While trade with the British did not fully recover, the U.S. expanded trade with France, the Netherlands, Portugal, and other European countries. Despite these good economic conditions, many traders complained of the high duties imposed by each state, which served to restrain interstate trade. Many creditors also suffered from the failure of domestic governments to repay debts incurred during the war. Though the 1780s saw moderate economic growth, many experienced economic anxiety, and Congress received much of the blame for failing to foster a stronger economy. On the positive side, the states gave Congress control of the western lands and an effective system for population expansion was developed. The Northwest Ordinance of 1787 abolished slavery in the area north of the Ohio River and promised statehood when a territory reached a threshold population, as Ohio did in 1803.

The new nation

The Constitution of the United States, adopted in 1787, established that the entire nation was a unified, or common market, with no internal tariffs or taxes on interstate commerce. The extent of federal power was much debated, with Alexander Hamilton taking a very broad view as the first Secretary of the Treasury during the presidential administration of George Washington. Hamilton successfully argued for the concept of "implied powers", whereby the federal government was authorized by the Constitution to create anything necessary to support its contents, even if it not specifically noted in it (build lighthouses, etc.). He succeeded in building strong national credit based on taking over the state debts and bundling them with the old national debt into new securities sold to the wealthy. They in turn now had an interest in keeping the new government solvent. Hamilton funded the debt with tariffs on imported goods and a highly controversial tax on whiskey. Hamilton believed the United States should pursue economic growth through diversified shipping, manufacturing, and banking. He sought and achieved Congressional authority to create the First Bank of the United States in 1791; the charter lasted until 1811.

After the war, the older cities finally restored their economic basis; newer growing cities included Salem, Massachusetts (which opened a new trade with China), New London, Connecticut, and Baltimore, Maryland. Secretary Hamilton set up a national bank in 1791. New local banks began to flourish in all the cities. Merchant entrepreneurship flourished and was a powerful engine of prosperity in the cities.

World peace lasted only a decade, for in 1793 two decades of war between Britain and France and their allies broke out. As the leading neutral trading partner the United States did business with both sides. France resented it, and the Quasi-War of 1798–99 disrupted trade. Outraged at British impositions on American merchant ships, and sailors, the Jefferson and Madison administrations engaged in economic warfare with Britain 1807–1812, and then full-scale warfare 1812 to 1815. The war cut off imports and encouraged the rise of American manufacturing.

Industry and commerce

Transportation

There were very few roads outside of cities and no canals in the new nation. In 1792 it was reported that the cost of transport of many crops to seaport was from one-fifth to one half their cost. The cheapest form of transportation was by water, along the seacoast or on lakes and rivers. In 1816 it was reported that "A ton of goods could be brought 3000 miles from Europe for about $9, but for that same sum it could be moved only 30 miles in this country".

Automatic flour mill

In the mid 1780s Oliver Evans invented a fully automatic mill that could process grain with practically no human labor or operator attention. This was a revolutionary development in two ways: 1) it used bucket elevators and conveyor belts, which would eventually revolutionize materials handling, and 2) it used governors, a forerunner of modern automation, for control.

Cotton gin

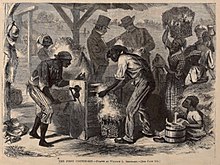

Cotton was at first a small-scale crop in the South. Cotton farming boomed following the improvement of the cotton gin by Eli Whitney. It was 50 times more productive at removing the seeds than with a roller. Soon, large cotton plantations, based on slave labor, expanded in the richest lands from the Carolinas westward to Texas. The raw cotton was shipped to textile mills in Britain, France and New England.

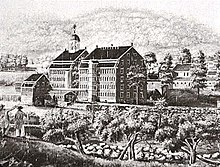

Mechanized textile manufacturing

In the final decade of the 18th century, England was beginning to enter the rapid growth period of the Industrial Revolution, but the rest of the world was completely devoid of any type of large scale mechanized industry. Britain prohibited the export of textile machinery and designs and did not allow mechanics with such skills to emigrate. Samuel Slater, who worked as mechanic at a cotton spinning operation in England, memorized the design of the machinery. He was able to disguise himself as a laborer and emigrated to the U.S., where he heard there was a demand for his knowledge. In 1789 Slater began working as a consultant to Almy & Brown in Rhode Island who were trying to successfully spin cotton on some equipment they had recently purchased. Slater determined that the machinery was not capable of producing good quality yarn and persuaded the owners to have him design new machinery. Slater found no mechanics in the U.S. when he arrived and had great difficulty finding someone to build the machinery. Eventually he located Oziel Wilkinson and his son David to produce iron castings and forgings for the machinery. According to David Wilkinson: "all the turning of the iron for the cotton machinery built by Mr. Slater was done with hand chisels or tools in lathes turned by cranks with hand power". By 1791 Slater had some of the equipment operating. In 1793 Slater and Brown opened a factory in Pawtucket, Rhode Island, which was the first successful water powered roller spinning cotton factory in the U.S. ( See: Slater Mill Historic Site ). David Wilkinson went on to invent a metalworking lathe which won him a Congressional prize.

Finance, money and banking

The First Bank of the United States was chartered in 1791. It was designed by Alexander Hamilton and faced strenuous opposition from agrarians led by Thomas Jefferson, who deeply distrusted banks and urban institutions. They closed the Bank in 1811, just when the War of 1812 made it more important than ever for Treasury needs.

Early 19th century

The United States was pre-industrial throughout the first third of the 19th century. Most people lived on farms and produced much of what they consumed. A considerable percentage of the non-farm population was engaged in handling goods for export. The country was an exporter of agricultural products. The U.S. built the best ships in the world.

The textile industry became established in New England, where there was abundant water power. Steam power began being used in factories, but water was the dominant source of industrial power until the Civil War.

The building of roads and canals, the introduction of steamboats and the first railroads were the beginning of a transportation revolution that would accelerate throughout the century.

Political developments

The institutional arrangements of the American System were initially formulated by Alexander Hamilton, who proposed the creation of a government-sponsored bank and increased tariffs to encourage industrial development. Following Hamilton's death, the American school of political economy was championed in the antebellum period by Henry Clay and the Whig Party generally.

Specific government programs and policies which gave shape and form to the American School and the American System include the establishment of the Patent Office in 1802; the creation of the Coast and Geodetic Survey in 1807 and other measures to improve river and harbor navigation; the various Army expeditions to the west, beginning with the Lewis and Clark Expedition in 1804 and continuing into the 1870s, almost always under the direction of an officer from the Army Corps of Topographical Engineers, and which provided crucial information for the overland pioneers that followed; the assignment of Army Engineer officers to assist or direct the surveying and construction of the early railroads and canals; the establishment of the First Bank of the United States and Second Bank of the United States as well as various protectionist measures (e.g., the tariff of 1828).

Thomas Jefferson and James Madison opposed a strong central government (and, consequently, most of Hamilton's economic policies), but they could not stop Hamilton, who wielded immense power and political clout in the Washington administration. In 1801, however, Jefferson became president and turned to promoting a more decentralized, agrarian democracy called Jeffersonian democracy. (He based his philosophy on protecting the common man from political and economic tyranny. He particularly praised small farmers as "the most valuable citizens".) However, Jefferson did not change Hamilton's basic policies. As president in 1811 Madison let the bank charter expire, but the War of 1812 proved the need for a national bank and Madison reversed positions. The Second Bank of the United States was established in 1816, with a 20-year charter.

Thomas Jefferson was able to purchase the Louisiana Territory from the Napoleon in 1803 for $15 million, with money raised in England. The Louisiana Purchase greatly expanded the size of the United States, adding extremely good farmland, the Mississippi River and the city of New Orleans. The French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars from 1793 to 1814 caused withdrawal of most foreign shipping from the U.S., leaving trade in the Caribbean and Latin America at risk for the seizure of American merchant ships by France and Britain. This led to Jefferson's Embargo Act of 1807 which prohibited most foreign trade. The War of 1812, by cutting off almost all foreign trade, created a home market for goods made in the U.S. (even if they were more expensive), changing an early tendency toward free trade into a protectionism characterized by nationalism and protective tariffs.

States built roads and waterways, such as the Cumberland Pike (1818) and the Erie Canal (1825), opening up markets for western farm products. The Whig Party supported Clay's American System, which proposed to build internal improvements (e.g. roads, canals and harbors), protect industry, and create a strong national bank. The Whig legislation program was blocked at the national level by the Jacksonian Democrats, but similar modernization programs were enacted in most states on a bipartisan basis.

The role of the Federal Government in regulating interstate commerce was firmly established by the landmark Supreme Court ruling in Gibbons v Ogden, which decided against allowing states to grant exclusive rights to steamboat companies operating between states.

President Andrew Jackson (1829–1837), leader of the new Democratic Party, opposed the Second Bank of the United States, which he believed favored the entrenched interests of the rich. When he was elected for a second term, Jackson blocked the renewal of the bank's charter. Jackson opposed paper money and demanded the government be paid in gold and silver coins. The Panic of 1837 stopped business growth for three years.

Agriculture, commerce and industry

Population growth

Although there was relatively little immigration from Europe, the rapid expansion of settlements to the West, and the Louisiana Purchase of 1803, opened up vast frontier lands. The high birth rate, and the availability of cheap land caused the rapid expansion of population. The average age was under 20, with children everywhere. The population grew from 5.3 million people in 1800, living on 865,000 square miles of land to 9.6 million in 1820 on 1,749,000 square miles. By 1840, the population had reached 17,069,000 on the same land.

New Orleans and St. Louis joined the United States and grew rapidly; entirely new cities were begun at Pittsburgh, Marietta, Cincinnati, Louisville, Lexington, Nashville and points west. The coming of the steamboat after 1810 made upstream traffic economical on major rivers, especially the Hudson, Ohio, Mississippi, Illinois, Missouri, Tennessee, and Cumberland rivers. Historian Richard Wade has emphasized the importance of the new cities in the Westward expansion in settlement of the farmlands. They were the transportation centers, and nodes for migration and financing of the westward expansion. The newly opened regions had few roads, but a very good river system in which everything flowed downstream to New Orleans. With the coming of the steamboat after 1815, it became possible to move merchandise imported from the Northeast and from Europe upstream to new settlements. The opening of the Erie Canal made Buffalo the jumping off point for the lake transportation system that made major trading centers in Cleveland, Detroit, and especially Chicago.

Labor shortage

The U.S. economy of the early 19th century was characterized by labor shortages. It was attributed to the cheapness of land and the high returns on agriculture. All types of labor were in high demand, especially unskilled labor and experienced factory workers. Wages in the U.S. were typically between 30 and 50 percent higher than in Britain. Women factory workers were especially scarce. The elasticity of labor was low in part because of lack of transportation and low population density. The relative labor scarcity and high price was an incentive for capital investment, particularly in machinery.

Agriculture

The U.S. economy was primarily agricultural in the early 19th century. Westward expansion plus the building of canals and the introduction of steamboats opened up new areas for agriculture. Much land was cleared and put into growing cotton in the Mississippi valley and in Alabama, and new grain growing areas were brought into production in the Midwest. Eventually this put severe downward pressure on prices, particularly of cotton, first from 1820 to 1823 and again from 1840 to 1843.

Before the Industrial Revolution most cotton was spun and woven near where it was grown, leaving little raw cotton for the international marketplace. World cotton demand experienced strong growth due to mechanized spinning and weaving technologies of the Industrial Revolution. Although cotton was grown in India, China, Egypt, the Middle East and other tropical and subtropical areas, the Americas, particularly the U.S., had sufficient suitable land available to support large scale cotton plantations, which were highly profitable. A strain of cotton seed brought from New Spain to Natchez, Mississippi, in 1806 would become the parent genetic material for over 90% of world cotton production today; it produced bolls that were three to four times faster to pick. The cotton trade, excluding financing, transport and marketing, was 6 percent or less of national income in the 1830s. Cotton became the United States' largest export.

Sugarcane was being grown in Louisiana, where it was refined into granular sugar. Growing and refining sugar required a large amount of capital. Some of the nation's wealthiest people owned sugar plantations, which often had their own sugar mills.

Southern plantations, which grew cotton, sugarcane and tobacco, used African slave labor. Per capita food production did not keep pace with the rapidly expanding urban population and industrial labor force in the Antebellum decades.

Roads

There were only a few roads outside of cities at the beginning of the 19th century, but turnpikes were being built. A ton-mile by wagon cost from between 30 and 70 cents in 1819. Robert Fulton's estimate for typical wagonage was 32 cents per ton-mile. The cost of transporting wheat or corn to Philadelphia exceeded the value at 218 and 135 miles, respectively. To facilitate westward expansion, in 1801 Thomas Jefferson began work on the Natchez Trace, which was to connect Daniel Boone's Wilderness Road, which ended in Nashville, Tennessee, with the Mississippi River.

Following the Louisiana Purchase the need for additional roads to the West were recognized by Thomas Jefferson, who authorized the construction of the Cumberland Road in 1806. The Cumberland Road was to connect Cumberland Maryland on the Potomac River with the Wheeling (West) Virginia on the Ohio River, which was on the other side of the Allegheny Mountains. Mail roads were also built to New Orleans.

The building of roads in the early years of the 19th century greatly lowered transportation costs and was a factor in the deflation of 1819 to 1821, which was one of the most severe in U.S. history.

Some turnpikes were wooden plank roads, which typically cost about $1,500 to $1,800 per mile, but wore out quickly. Macadam roads in New York cost an average of $3,500 per mile, while high-quality roads cost between $5,000 and $10,000 per mile.

Canals

Because a horse can pull a barge carrying a cargo of over 50 tons compared to the typical one ton or less hauled by wagon, and the horse required a wagoner versus a couple of men for the barge, water transportation costs were a small fraction of wagonage costs. Canals' shipping costs were between two and three cents per ton-mile, compared to 17–20 cents by wagon. The cost of constructing a typical canal was between $20,000 and $30,000 per mile.

Only 100 miles of canals had been built in the U.S. by 1816, and only a few were longer than two miles. The early canals were typically financially successful, such as those carrying coal in the Coal Region of Northeastern Pennsylvania, where canal construction was concentrated until 1820.

The 325-mile Erie Canal, which connected Albany, New York, on the Hudson River with Buffalo, New York, on Lake Erie, began operation in 1825. Wagon cost from Buffalo to New York City in 1817 was 19.2 cents per ton-mile. By Erie Canal c. 1857 to 1860 the cost was 0.81 cents. The Erie Canal was a great commercial success and had a large regional economic impact.

The Delaware and Raritan Canal was also very successful. Also important was the 2.5-mile canal bypassing the falls of the Ohio River at Louisville, which opened in 1830.

The success of some of the early canals led to a canal building boom, during which work began on many canals which would prove to be financially unsuccessful. As the canal boom was underway in the late 1820s, a small number of horse railways were being built. These were quickly followed by the first steam railways in the 1830s.

Steam power

In 1780 the United States had three major steam engines, all of which were used for pumping water: two in mines and one for New York City's water supply. Most power in the U.S. was supplied by water wheels and water turbines after their introduction in 1840. By 1807 when the North River Steamboat (unofficially called Clermont) first sailed, there were estimated to be fewer than a dozen steam engines operating in the U.S. Steam power did not overtake water power until sometime after 1850.

Oliver Evans began developing a high pressure steam engine that was more practical than the engine developed around the same time by Richard Trevithick in England. The high pressure engine did away with the separate condenser and thus did not require cooling water. It also had a higher power to weight ratio, making it suitable for powering steamboats and locomotives.

Evans produced a few custom steam engines from 1801 to 1806, when he opened the Mars Works iron foundry and factory in Philadelphia, where he produced additional engines. In 1812 he produced a successful Colombian engine at Mars Works. As his business grew and orders were being shipped, Evans and a partner formed the Pittsburgh Steam Engine Company in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Steam engines soon became common in public water supply, sawmills and flour milling, especially in areas with little or no water power.

Mechanical power transmission

In 1828 Paul Moody substituted leather belting for gearing in mills. Leather belting from line shafts was the common way to distribute power from steam engines and water turbines in mills and factories. In the factory boom of the late 19th century it was common for large factories to have many miles of line shafts. Leather belting continued in use until it was displaced by unit drive electric motors in the early decades of the 20th century.

Shipbuilding

Shipbuilding remained a sizable industry. U.S.-built ships were superior in design, required smaller crews and cost between 40 and 60 percent less to build than European ships. The British gained the lead in shipbuilding after they introduced iron-hulled ships in the mid-19th century.

Steamboats and steam ships

Commercial steamboat operations began in 1807 within weeks of the launch of Robert Fulton's North River Steamboat, often referred to as the Clermont.

The first steamboats were powered by Boulton and Watt type low pressure engines, which were very large and heavy in relation to the smaller high pressure engines. In 1807 Robert L. Stevens began operation of the Phoenix, which used a high pressure engine in combination with a low pressure condensing engine. The first steamboats powered only by high pressure were the Aetna and Pennsylvania designed and built by Oliver Evans.

In the winter of 1811 to 1812, the New Orleans became the first steamboat to travel down the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers from Pittsburgh to New Orleans. The commercial feasibility of steamboats on the Mississippi and its tributaries was demonstrated by the Enterprise in 1814.

By the time of Fulton's death in 1815 he operated 21 of the estimated 30 steamboats in the U.S. The number of steamboats steadily grew into the hundreds. There were more steamboats in the Mississippi valley than anywhere else in the world.

Early steamboats took 30 days to travel from New Orleans to Louisville, which was from half to one-quarter the time by keel boat. Due to improvements in steamboat technology, by 1830 the time from New Orleans to Louisville was halved. In 1820 freight rates for keel boats were five cents per ton-mile versus two cents by steamboat, falling to one-half cent per pound by 1830.

The SS Savannah crossed from Savannah to Liverpool in 1819 as the first trans-Atlantic steamship; however, until the development of more efficient engines, trans-ocean ships had to carry more coal than freight. Early trans-ocean steamships were used for passengers and soon some companies began offering regularly scheduled service.

Railroads

Railroads were an English invention, and the first entrepreneurs imported British equipment in the 1830s. By the 1850s the Americans had developed their own technology. The early lines in the 1830s and 1840s were locally funded, and connected nearby cities or connected farms to navigable waterways. They primarily handled freight rather than passengers. The first locomotives were imported from England. One such locomotive was the John Bull which arrived in 1831. While awaiting assembly, Matthias W. Baldwin, who had designed and manufactured a highly successful stationary steam engine, was able to inspect the parts and obtain measurements. Baldwin was already working on an experimental locomotive based on designs shown at the Rainhill Trials in England. Baldwin produced his first locomotive in 1832; he went on to found the Baldwin Locomotive Works, one of the largest locomotive manufacturers. In 1833 when there were few locomotives in the U.S., three quarters were made in England. In 1838 there were 346 locomotives, three-fourths of which were made in the U.S.

Ohio had more railroads built in the 1840s than any other state. Ohio's railroads put the canals out of business. A typical mile of railroad cost $30,000 compared to the $20,000 per mile of canal, but a railroad could carry 50 times as much traffic. Railroads appeared at the time of the canal boom, causing its abrupt end, although some canals flourished for an additional half-century.

Manufacturing

Starting with textiles in the 1790s, factories were built to supply a regional and national market. The power came from waterfalls, and most of the factories were built alongside the rivers in rural New England and Upstate New York.

Before 1800, most cloth was made in home workshops, and housewives sewed it into clothing for family use or trade with neighbors. In 1810 the secretary of the treasury estimated that two-thirds of rural household clothing, including hosiery and linen, was produced by households. By the 1820s, housewives bought the cloth at local stores, and continued their sewing chores. The American textile industry was established during the long period of wars from 1793 to 1815, when cheap cloth imports from Britain were unavailable. Samuel Slater secretly brought in the plans for complex textile machinery from Britain, and built new factories in Rhode Island using the stolen designs. By the time the Embargo Act of 1807 cut off trade with Britain, there were 15 cotton spinning mills in operation. These were all small operations, typically employing fewer than 50 people, and most used Arkwright water frames powered by small streams. They were all located in southeastern New England.

In 1809 the number of mills had grown to 62, with 25 under construction. To meet increased demand for cloth several manufacturers resorted to the putting-out system of having the handloom weaving done in homes. The putting-out system was inefficient because of the difficulty of distributing the yarn and collecting the cloth, embezzlement of supplies, lack of supervision and poor quality. To overcome these problems the textile manufacturers began to consolidate work in central workshops shops where they could supervise operations. Taking this to the next level, in 1815 Francis Cabot Lowell of the Boston Manufacturing Company built the first integrated spinning and weaving factory in the world at Waltham, Massachusetts, using plans for a power loom that he smuggled out of England. This was the largest factory in the U.S., with a workforce of about 300. It was a very efficient, highly profitable mill that, with the aid of the Tariff of 1816, competed effectively with British textiles at a time when many smaller operations were being forced out of business.

The Fall River Manufactory, located on the Quequechan River in Fall River, Massachusetts, was founded in 1813 by Dexter Wheeler and cousin David Anthony. By 1827 there were 10 cotton mills in the Fall River area, which soon became the country's leading producer of printed cotton cloth.

Beginning with Lowell, Massachusetts, in the 1820s, large-scale factory towns, mostly mill towns, began growing around rapidly expanding manufacturing plants, especially in New England, New York, and New Jersey. Some were established as company towns, where either from idealism or economic exploitation, the same corporation that owned the factory also owned all local worker housing and retail establishments. This paternalistic model experienced significant pushback with the Pullman Strike of 1894, and significantly declined with increasing worker affluence during the Roaring Twenties, development of the automobile that allowed workers to live outside of the factory town, and New Deal policies.

The U.S. began exporting textiles in the 1830s; the Americans specialized in coarse fabrics, while the British exported finer cloth that reached a somewhat different market. Cloth production—mostly cotton but also wool, linen and silk—became the leading American industry. The building of textile machinery became a major driving force in the development of advanced mechanical devices.

The shoe industry began transitioning from production by craftsmen to the factory system, with division of labor.

Low return freight rates from Europe offered little protection from imports to domestic industries.

Development of interchangeable parts

Standardization and interchangeability have been cited as major contributors to the exceptional growth of the U.S. economy.

The idea of standardization of armaments was originated the 1765 by French Gribeauval system. Honoré Blanc began producing muskets with interchangeable locks in France when Thomas Jefferson was minister to France. Jefferson wrote a letter to John Jay about these developments in 1785. The idea of armament standardization was advocated by Louis de Tousard, who fled the French Revolution and in 1795 joined the U.S. Corps of Artillerists and Engineers where he taught artillery and engineering. At the suggestion of George Washington, Tousard wrote The American Artillerist's Companion (1809). This manual became a standard textbook for officer training; it stressed the importance of a system of standardized armaments.

Fears of war stemming from the XYZ Affair caused the U.S. to begin offering cash advance contracts for producing small arms to private individuals in 1798. Two notable recipients of these contracts associated with interchangeable parts were Eli Whitney and Simeon North. Although Whitney was not able to make interchangeable parts, he was a proponent of using machinery for gun making; however, he employed only the simplest machines in his factory. North eventually made progress toward some degree of interchangeability and developed special machinery. North's shop used the first known milling machine (c. 1816), a fundamental machine tool.

The experience of the War of 1812 led the War Department to issue a request for contract proposals for firearms with interchangeable parts. Previously, parts from each firearm had to be carefully custom fitted; almost all infantry regiments necessarily included an artificer or armorer who could perform this intricate gunsmithing. The requirement for interchangeable parts forced the development of modern metal-working machine tools, including milling machines, grinders, shapers and planers. The Federal Armories perfected the use of machine tools by developing fixtures to correctly position the parts being machined and jigs to guide the cutting tools over the proper path. Systems of blocks and gauges were also developed to check the accuracy and precision of the machined parts. Developing the manufacturing techniques for making interchangeable parts by the Federal Armories took over two decades; however, the first interchangeable small arms parts were not made to a high degree of precision. It wasn't until the mid-century or later that parts for U.S. rifles could be considered truly interchangeable with a degree of precision. In 1853 when the British Parliamentary Committee on Small Arms questioned gun maker Samuel Colt, and machine tool makers James Nasmyth and Joseph Whitworth, there was still some question about what constituted interchangeability and whether it could be achieved at a reasonable cost.

The machinists' skills were called armory practice and the system eventually became known as the American system of manufacturing. Machinists from the armories eventually spread the technology to other industries, such as clocks and watches, especially in the New England area. It wasn't until late in the 19th century that interchangeable parts became widespread in U.S. manufacturing. Among the items using interchangeable parts were some sewing machine brands and bicycles.

The development of these modern machine tools and machining practices made possible the development of modern industry capable of mass production; however, large scale industrial production did not develop in the U.S. until the late 19th century.

Finance, money and banking

The charter for the First Bank of the United States expired in 1811. Its absence caused serious difficulties for the national government trying to finance the War of 1812 over the refusal of New England bankers to help out.

President James Madison reversed earlier Jeffersonian opposition to banking, and secured the opening of a new national bank. The Second Bank of the United States was chartered in 1816. Its leading executive was Philadelphia banker Nicholas Biddle. It collapsed in 1836, under heavy attack from President Andrew Jackson during his Bank War.

There were three economic downturns in the early 19th century. The first was the result of the Embargo Act of 1807, which shut off most international shipping and trade due to the Napoleonic Wars. The embargo caused a depression in cities and industries dependent on European trade. The other two downturns were depressions accompanied by significant periods of deflation during the early 19th century. The first and most severe was during the depression from 1818 to 1821 when prices of agricultural commodities declined by almost 50 percent. A credit contraction caused by a financial crisis in England drained specie out of the U.S. The Bank of the United States also contracted its lending. The price of agricultural commodities fell by almost 50 percent from the high in 1815 to the low in 1821, and did not recover until the late 1830s, although to a significantly lower price level. Most damaging was the price of cotton, the U.S.'s main export. Food crop prices, which had been high because of the famine of 1816 that was caused by the year without a summer, fell after the return of normal harvests in 1818. Improved transportation, mainly from turnpikes, significantly lowered transportation costs.

The third economic downturn was the depression of the late 1830s to 1843, following the Panic of 1837, when the money supply in the United States contracted by about 34 percent with prices falling by 33 percent. The magnitude of this contraction is matched only by the Great Depression. A fundamental cause of the Panic of 1837 was depletion of Mexican silver mines. Despite the deflation and depression, GDP rose 16 percent from 1839 to 1843, partly because of rapid population growth.

In order to dampen speculation in land, Andrew Jackson signed the executive order known as the Specie Circular in 1836, requiring sale of government land to be paid in gold and silver. Branch mints at New Orleans; Dahlonega, Georgia; and Charlotte, North Carolina, were authorized by congress in 1835 and became operational in 1838.

Gold was being withdrawn from the U.S. by England and silver had also been taken out of the country because it had been undervalued relative to gold by the Coinage Act of 1834. Canal projects began to fail. The result was the financial Panic of 1837. In 1838 there was a brief recovery. The business cycle upturn occurred in 1843.

Economic historians have explored the high degree of financial and economic instability in the Jacksonian era. For the most part, they follow the conclusions of Peter Temin, who absolved Jackson's policies, and blamed international events beyond American control, such as conditions in Mexico, China and Britain. A survey of economic historians in 1995 show that the vast majority concur with Temin's conclusion that "the inflation and financial crisis of the 1830s had their origin in events largely beyond President Jackson's control and would have taken place whether or not he had acted as he did vis-a-vis the Second Bank of the U.S."

Economics of the War of 1812

The War of 1812 was financed by borrowing, by new issues of private bank notes and by an inflation in prices of 15%. The government was a very poor manager during the war, with delays in payments and confusion, as the Treasury took in money months after it was scheduled to pay it out. Inexperience, indecision, incompetence, partisanship and confusion are the main hallmarks. The federal government's management system was designed to minimize the federal role before 1812. The Democratic-Republican Party in power deliberately wanted to downsize the power and roles of the federal government; when the war began, the Federalist opposition worked hard to sabotage operations. Problems multiplied rapidly in 1812, and all the weaknesses were magnified, especially regarding the Army and the Treasury. There were no serious reforms before the war ended. In financial matters, the decentralizing ideology of the Republicans meant they wanted the First Bank of the United States to expire in 1811, when its 20-year charter ran out. Its absence made it much more difficult to handle the financing of the war, and caused special problems in terms of moving money from state to state, since state banks were not allowed to operate across state lines. The bureaucracy was terrible, often missing deadlines. On the positive side, over 120 new state banks were created all over the country, and they issued notes that financed much of the war effort, along with loans raised by Washington. Some key Republicans, especially Secretary of the Treasury Albert Gallatin realized the need for new taxes, but the Republican Congress was very reluctant and only raised small amounts. The whole time, the Federalist Party in Congress and especially the Federalist-controlled state governments in the Northeast, and the Federalist-aligned financial system in the Northeast, was strongly opposed to the war and refused to help in the financing. Indeed, they facilitated smuggling across the Canadian border, and sent large amounts of gold and silver to Canada, which created serious shortages of specie in the US.

Across the two and half years of the war, 1812–1815, the federal government took in more money than it spent. Cash out was $119.5 million, cash in was $154.0 million. Two-thirds of the income was borrowed and had to be paid back in later years; the national debt went from $56.0 million in 1812 to $127.3 million in 1815. Out of the GDP (gross domestic product) of about $925 million (in 1815), this was not a large burden for a national population of 8 million people; it was paid off in 1835. A new Second Bank of the United States was set up in 1816, and after that the financial system performed very well, even though there was still a shortage of gold and silver.

The economy grew every year 1812–1815, despite a large loss of business by East Coast shipping interests. Wartime inflation averaged 4.8% a year. The national economy grew 1812–1815 at the rate of 3.7% a year, after accounting for inflation. Per capita GDP grew at 2.2% a year, after accounting for inflation. Money that would have been spent on imports—mostly cloth—was diverted to opening new factories, which were profitable since British cloth was not available. This gave a major boost to the industrial revolution, as typified by the Boston Associates. The Boston Manufacturing Company built the first integrated spinning and weaving factory in the world at Waltham, Massachusetts, in 1813.

Middle 19th century

The middle 19th century was a period of transition toward industrialization, particularly in the Northeast, which produced cotton textiles and shoes. The population of the West (generally meaning from Ohio to and including Wisconsin, Minnesota, Iowa and Missouri and south to include Kentucky) grew rapidly. The West was primarily a grain and pork producing region, with an important machine tool industry developing around Cincinnati, Ohio. The Southern economy was based on plantation agriculture, primarily cotton, tobacco and sugar, produced with slave labor.

The market economy and factory system were not typical before 1850, but developed along transportation routes. Steamboats and railroads, introduced in the early part of the century, became widespread and aided westward expansion. The telegraph was introduced in 1844 and was in widespread use by the mid 1850s.

A machine tool industry developed and machinery became a major industry. Sewing machines began being manufactured. The shoe industry became mechanized. Horse drawn reapers became widely introduced, significantly increasing the productivity of farming.

The use of steam engines in manufacturing increased and steam power exceeded water power after the Civil War. Coal replaced wood as the major fuel.

The combination of railroads, the telegraph and machinery and factories began to create an industrial economy.

The longest economic expansion of the United States occurred in the recession-free period between 1841 and 1856. A 2017 study attributes this expansion primarily to "a boom in transportation-goods investment following the discovery of gold in California."

Commerce, industry and agriculture

The depression that began in 1839 ended with an upswing in economic activity in 1843.

| Employment % | Output % (1860 prices) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | Agriculture | Industry | Services | Agriculture | Industry | Services |

| 1840 | 68 | 12 | 20 | 47 | 21 | 31 |

| 1850 | 60 | 17 | 23 | 42 | 29 | 29 |

| 1860 | 56 | 19 | 25 | 38 | 28 | 34 |

| 1870 | 53 | 22 | 25 | 35 | 31 | 34 |

| 1880 | 52 | 23 | 25 | 31 | 32 | 38 |

| 1890 | 43 | 26 | 31 | 22 | 41 | 37 |

| 1900 | 40 | 26 | 33 | 20 | 40 | 39 |

| Source: Joel Mokyr | ||||||

Railroads

Railroads opened up remote areas and drastically cut the cost of moving freight and passengers. By 1860 long distance bulk rates had fallen by 95%, less than half of which was due to the general fall in prices. This large fall in transportation costs created "a major revolution in domestic commerce."

As transportation improved, new markets continuously opened. Railroads greatly increased the importance of hub cities such as Atlanta, Billings, Chicago, and Dallas.

Railroads were a highly capital intensive business, with a typical cost of $30,000 per mile with a considerable range depending on terrain and other factors. Private capital for Railroads during the period from 1830 to 1860 was inadequate. States awarded charters, funding, tax breaks, land grants, and provided some financing. Railroads were allowed banking privileges and lotteries in some states. Private investors provided a small but not insignificant share or railroad capital. A combination of domestic and foreign investment along with the discovery of gold and a major commitment of America's public and private wealth, enabled the nation to develop a large-scale railroad system, establishing the base for the country's industrialization.

|

|

1850 | 1860 | 1870 | 1880 | 1890 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| New England | 2,507 | 3,660 | 4,494 | 5,982 | 6,831 |

| Middle States | 3,202 | 6,705 | 10,964 | 15,872 | 21,536 |

| Southern States | 2,036 | 8,838 | 11,192 | 14,778 | 29,209 |

| Western States and Territories | 1,276 | 11,400 | 24,587 | 52,589 | 62,394 |

| Pacific States and Territories |

|

23 | 1,677 | 4,080 | 9,804 |

| TOTAL NEW TRACK USA | 9,021 | 30,626 | 52,914 | 93,301 | 129,774 |

| Source: Chauncey M. Depew (ed.), One Hundred Years of American Commerce 1795–1895 p. 111 | |||||

Railroad executives invented modern methods for running large-scale business operations, creating a blueprint that all large corporations basically followed. They created career tracks that took 18-year-old boys and turned them into brakemen, conductors and engineers. They were first to encounter managerial complexities, labor union issues, and problems of geographical competition. Due to these radical innovations, the railroad became the first large-scale business enterprise and the model for most large corporations.

Historian Larry Haeg argues from the perspective of the end of the 19th century:

- Railroads created virtually every major American industry: coal, oil, gas, steel, lumber, farm equipment, grain, cotton, textile factories, California citrus.

Iron industry

The most important technological innovation in mid-19th-century pig iron production was the adoption of hot blast, which was developed and patented in Scotland in 1828. Hot blast is a method of using heat from the blast furnace exhaust gas to preheat combustion air, saving a considerable amount of fuel. It allowed much higher furnace temperatures and increased the capacity of furnaces.

Hot blast allowed blast furnaces to use anthracite or lower grade coal. Anthracite was difficult to light with cold blast. High quality metallurgical coking coal deposits of sufficient size for iron making were only available in Great Britain and western Germany in the 19th century, but with less fuel required per unit of iron, it was possible to use lower grade coal.

The use of anthracite was rather short lived because the size of blast furnaces increased enormously toward the end of the century, forcing the use of coke, which was more porous and did not impede the upflow of the gases through the furnace. Charcoal would have been crushed by the column of material in tall furnaces. Also, the capacity of furnaces would have eventually exceeded the wood supply, as happened with locomotives.

Iron was used for a wide variety of purposes. In 1860 large consumers were numerous types of castings, especially stoves. Of the $32 million of bar, sheet and railroad iron produced, slightly less than half was railroad iron. The value added by stoves was equal to the value added by rails.

Coal displaces wood

Coal replaced wood during the mid-19th century. In 1840 wood was the major fuel while coal production was minor. In 1850 wood was 90% of fuel consumption and 90% of that was for home heating. By 1880 wood was only 5% of fuel consumption. Cast iron stoves for heating and cooking displaced inefficient fireplaces. Wood was a byproduct of land clearing and was placed along the banks of rivers for steamboats. By mid-century the forests were being depleted while steamboats and locomotives were using enough wood to create shortages along their routes; however, railroads, canals and navigable internal waterways were able to bring coal to market at a price far below the cost of wood. Coal sold in Cincinnati for 10 cents per bushel (94 pounds) and in New Orleans for 14 cents.

Charcoal production was very labor and land intensive. It was estimated that to fuel a typical sized 100 ton of pig iron per week furnace in 1833 at a sustained yield, a timber plantation of 20,000 acres was required. The trees had to be hauled by oxen to where they were cut, stacked on end and covered with earth or put in a kiln to be charred for about a week. Anthracite reduced labor cost to $2.50 per ton compared to charcoal at $15.50 per ton.

Manufacturing

Manufacturing became well established during the mid-19th century. Labor in the U.S. was expensive and industry made every effort to economize by using machinery. Woodworking machinery such as circular saws, high speed lathes, planers and mortising machines and various other machines amazed British visitors, as was reported by Joseph Whitworth. See: American system of manufacturing#Use of machinery

In the early 19th century machinery was made mostly of wood with iron parts. By the mid-century machines were being increasingly of all iron, which allowed them to operate at higher speeds and with higher precision. The demand for machinery created a machine tool industry that designed and manufactured lathes, metal planers, shapers and other precision metal cutting tools.

The shoe industry was the second to be mechanized, beginning in the 1840s. Sewing machines were developed for sewing leather. A leather rolling machine eliminated hand hammering, and was thirty times faster. Blanchard lathes began being used for making shoe lasts (forms) in the 1850s, allowing the manufacture of standard sizes.

By the 1850s much progress had been made in the development of the sewing machine, with a few companies making the machines, based on a number of patents, with no company controlling the right combination of patents to make a superior machine. To prevent damaging lawsuits, in 1856 several important patents were pooled under the Sewing Machine Combination, which licensed the patents for a fixed fee per machine sold.

The sewing machine industry was a beneficiary of machine tools and the manufacturing methods developed at the Federal Armories. By 1860 two sewing machine manufacturers were using interchangeable parts.

The sewing machine increased the productivity of sewing cloth by a factor of 5.

In 1860 the textile industry was the largest manufacturing industry in terms of workers employed (mostly women and children), capital invest and value of goods produced. That year there were 5 million spindles in the U.S.

Steam power

The Treasury Department's steam engine report of 1838 was the most valuable survey of steam power until the 1870 Census. According to the 1838 report there were an estimated 2,000 engines totaling 40,000 hp, of which 64% were used in transportation, mostly in steamboats.

The Corliss steam engine, patented in 1848, was called the most significant development in steam engineering since James Watt. The Corliss engine was more efficient than previous engines and maintained more uniform speed in response to load changes, making it suitable for a wide variety of industrial applications. It was the first steam engine that was suitable for cotton spinning. Previously steam engines for cotton spinning pumped water to a water wheel that powered the machinery.

Steam power greatly expanded during the late 19th century with the rise of large factories, the expanded railroad network and early electric lighting and electric street railways.

Steamboats and ships

The number of steamboats on western rivers in the U.S. grew from 187 in 1830 to 735 in 1860. Total registered tonnage of steam vessels for the U.S. grew from 63,052 in 1830 to 770,641 in 1860.

Until the introduction of iron ships, the U. S. made the best in the world. The design of U.S. ships required fewer crew members to operate. U.S. made ships cost from 40% to 60% as much as European ships, and lasted longer.

The screw propeller was tested on Lake Ontario in 1841 before being used on ocean ships. Propellers began being used on Great Lakes ships in 1845. Propellers caused vibrations which were a problem for wooden ships. The SS Great Britain, launched in 1845, was the first iron ship with a screw propeller. Iron ships became common and more efficient multiple expansion engines were developed. After the introduction of iron ships, Britain became the leading shipbuilding country. The U.S. tried to compete by building wooden clipper ships, which were fast, but too narrow to carry economic volumes of low value freight.

Telegraph

Congress approved funds for a short demonstration telegraph line from Baltimore to Washington D.C., which was operational in 1844. The telegraph was quickly adopted by the railroad industry, which needed rapid communication to coordinate train schedules, the importance of which had been highlighted by a collision on the Western Railroad in 1841. Railroads also needed to communicate over a vast network in order to keep track of freight and equipment. Consequently, railroads installed telegraphs lines on their existing right-of-ways. By 1852 there were 22,000 miles of telegraph lines in the U.S., compared to 10,000 miles of track.

Urbanization

By 1860, on the eve of the Civil War, 16% of the people lived in cities with 2500 or more people and one third of the nation's income came from manufacturing. Urbanized industry was limited primarily to the Northeast; cotton cloth production was the leading industry, with the manufacture of shoes, woolen clothing, and machinery also expanding. Most of the workers in the new factories were immigrants or their children. Between 1845 and 1855, some 300,000 European immigrants arrived annually. Many remained in eastern cities, especially mill towns and mining camps, while those with farm experience and some savings bought farms in the West.

Agriculture

In the antebellum period the U.S. supplied 80% of Britain's cotton imports. Just before the Civil War the value of cotton was 61% of all goods exported from the U.S.

The westward expansion into the highly productive heartland was aided by the new railroads, and both population and grain production in the West expanded dramatically. Increased grain production was able to capitalize on high grain prices caused by poor harvests in Europe during the time of the Great Famine in Ireland Grain prices also rose during the Crimean War, but when the war ended U.S. exports to Europe fell dramatically, depressing grain prices. Low grain prices were a cause of the Panic of 1857. Cotton and tobacco prices recovered after the panic.

Agriculture was the largest single industry and it prospered during the war. Prices were high, pulled up by a strong demand from the army and from Britain, which depended on American wheat for a fourth of its food imports.

John Deere developed a cast steel plow in 1837 which was lightweight and had a moldboard that efficiently turned over and shed the plowed earth. It was easy for a horse to pull and was well suited to cutting the thick prairie sod of the Midwest. He and his brother Charles founded Deere and Company which continues into the 21st century as the largest maker of tractors, combines, harvesters and other farm implements.

Threshing machines, which were a novelty at the end of the 18th century, began being widely introduced in the 1830s and 1840s. Mechanized threshing required less than half the labor of hand threshing.

The Civil War acted as a catalyst that encouraged the rapid adoption of horse-drawn machinery and other implements. The rapid spread of recent inventions such as the reaper and mower made the workforce efficient, even as hundreds of thousands of farmers were in the army. Many wives took their place, and often consulted by mail on what to do; increasingly they relied on community and extended kin for advice and help.

The 1862 Homestead Act opened up the public domain lands for free. Land grants to the railroads meant they could sell tracts for family farms (80 to 200 acres) at low prices with extended credit. In addition the government sponsored fresh information, scientific methods and the latest techniques through the newly established Department of Agriculture and the Morrill Land Grant College Act.

Slave labor

In 1860, there were 4.5 million Americans of African descent, 4 million of which were slaves, worth $3 billion. They were mainly owned by southern planters of cotton and sugarcane. An estimated 60% of the value of farms in Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi and South Carolina was in slaves, with less than a third in land and buildings.

In the aftermath of the Panic of 1857, which left many northern factory workers unemployed and deprived to the point of causing bread riots, supporters of slavery pointed out that slaves were generally better fed and had better living quarters than many free workers. It is estimated that slaves received 15% more in imputed wages than the free market.

Finance, money and banking

After the expiration of the charter of the Second Bank of the United States, federal revenues were handled by the Independent Treasury beginning in 1846. The Second Bank of the U.S. had also maintained some control over other banks, but in its absence banks were only under state regulation.

One of the main problems with banks was over-issuance of banknotes. These were redeemable in specie (gold or silver) upon presentation to the chief cashier of the bank. When people lost trust in a bank they rushed to redeem its notes, and because banks issued more notes than their specie reserves, the bank couldn't redeem the notes, often causing the bank to fail. In 1860 there were over 8,000 state chartered banks issuing notes. In 1861 the U.S. began issuing United States Notes as legal tender.

Banks began paying interest on deposits and using the proceeds to make short term call loans, mainly to stock brokers.

New York banks created a clearing house association in 1853 in which member banks cleared accounts with other city banks at the close of the week. The clearinghouse association also handled notes from banks in other parts of the country. The association was able to detect banks that were issuing excessive notes because they could not settle.

Panic of 1857

The recovery from the depression that followed the Panic of 1837 began in 1843 and lasted until the Panic of 1857.

The panic was triggered by the August 24 failure of the well regarded Ohio Life Insurance and Trust Co. A manager in the New York branch, one of the city's largest financial institutions, had embezzled funds and made excessive loans. The company's president announced suspension of specie redemption, which triggered a rush to redeem banknotes, causing many banks to fail because of lack of specie.