In philosophy, being refers to the existence of a thing. Anything that exists has being. Ontology is the branch of philosophy that studies being. Being is a concept encompassing objective and subjective features of reality and existence. Anything that partakes in being is also called a "being", though often this usage is limited to entities that have subjectivity (as in the expression "human being"). The notion of "being" has, inevitably, been elusive and controversial in the history of philosophy, beginning in Western philosophy with attempts among the pre-Socratics to deploy it intelligibly. The first effort to recognize and define the concept came from Parmenides, who famously said of it that "what is-is". Common words such as "is", "are", and "am" refer directly or indirectly to being.

As an example of efforts in recent times, Martin Heidegger (who himself drew on ancient Greek sources) adopted after German terms like Dasein to articulate the topic. Several modern approaches build on such continental European exemplars as Heidegger, and apply metaphysical results to the understanding of human psychology and the human condition generally (notably in the Existentialist tradition). By contrast, in mainstream Analytical philosophy the topic is more confined to abstract investigation, in the work of such influential theorists as W. V. O. Quine, to name one of many. One of the most fundamental questions that continues to exercise philosophers is posed by William James: "How comes the world to be here at all instead of the nonentity which might be imagined in its place? ... from nothing to being there is no logical bridge."

The substantial being

Being and the substance theorists

The deficit of such a bridge was first encountered in history by the Pre-Socratic philosophers during the process of evolving a classification of all beings (noun). Aristotle, who wrote after the Pre-Socratics, applies the term category (perhaps not originally) to ten highest-level classes. They comprise one category of substance (ousiae) existing independently (man, tree) and nine categories of accidents, which can only exist in something else (time, place). In Aristotle, substances are to be clarified by stating their definition: a note expressing a larger class (the genus) followed by further notes expressing specific differences (differentiae) within the class. The substance so defined was a species. For example, the species, man, may be defined as an animal (genus) that is rational (difference). As the difference is potential within the genus; that is, an animal may or may not be rational, the difference is not identical to, and may be distinct from, the genus.Applied to being, the system fails to arrive at a definition for the simple reason that no difference can be found. The species, the genus, and the difference are all equally being: a being is a being that is being. The genus cannot be nothing because nothing is not a class of everything. The trivial solution that being is being added to nothing is only a tautology: being is being. There is no simpler intermediary between being and non-being that explains and classifies being.

The Being according to Parmenides is like the mass of a sphere.

Pre-Socratic reaction to this deficit was varied. As substance theorists they accepted a priori the hypothesis that appearances are deceiving, that reality is to be reached through reasoning. Parmenides reasoned that if everything is identical to being and being is a category of the same thing then there can be neither differences between things nor any change. To be different, or to change, would amount to becoming or being non-being; that is, not existing. Therefore, being is a homogeneous and non-differentiated sphere and the appearance of beings is illusory. Heraclitus, on the other hand, foreshadowed modern thought by denying existence. Reality does not exist, it flows, and beings are an illusion upon the flow.

Aristotle knew of this tradition when he began his Metaphysics, and had already drawn his own conclusion, which he presented under the guise of asking what being is:

"And indeed the question which was raised of old is raised now and always, and is always the subject of doubt, viz., what being is, is just the question, what is substance? For it is this that some assert to be one, others more than one, and that some assert to be limited in number, others unlimited. And so we also must consider chiefly and primarily and almost exclusively what that is which is in this sense."and reiterates in no uncertain terms: "Nothing, then, which is not a species of a genus will have an essence – only species will have it ....". Being, however, for Aristotle, is not a genus.

Aristotle's theory of act and potency

One might expect a solution to follow from such certain language but none does. Instead Aristotle launches into a rephrasing of the problem, the Theory of Act and Potency. In the definition of man as a two-legged animal Aristotle presumes that "two-legged" and "animal" are parts of other beings, but as far as man is concerned, are only potentially man. At the point where they are united into a single being, man, the being, becomes actual, or real. Unity is the basis of actuality: "... 'being' is being combined and one, and 'not being' is being not combined but more than one." Actuality has taken the place of existence, but Aristotle is no longer seeking to know what the actual is; he accepts it without question as something generated from the potential. He has found a "half-being" or a "pre-being", the potency, which is fully being as part of some other substance. Substances, in Aristotle, unite what they actually are now with everything they might become.The transcendental being

Some of Thomas Aquinas' propositions were reputedly condemned by Étienne Tempier, the local Bishop of Paris (not the Papal Magisterium itself) in 1270 and 1277, but his dedication to the use of philosophy to elucidate theology was so thorough that he was proclaimed a Doctor of the Church in 1568. Those who adopt it are called Thomists.Thomistic analogical predication of being

In a single sentence, parallel to Aristotle's statement asserting that being is substance, St. Thomas pushes away from the Aristotelian doctrine: "Being is not a genus, since it is not predicated univocally but only analogically." His term for analogy is Latin analogia. In the categorical classification of all beings, all substances are partly the same: man and chimpanzee are both animals and the animal part in man is "the same" as the animal part in chimpanzee. Most fundamentally all substances are matter, a theme taken up by science, which postulated one or more matters, such as earth, air, fire or water (Empedocles). In today's chemistry the carbon, hydrogen, oxygen and nitrogen in a chimpanzee are identical to the same elements in a man.The original text reads, "Although equivocal predications must be reduced to univocal, still in actions, the non-univocal agent must precede the univocal agent. For the non-univocal agent is the universal cause of the whole species, as for instance the sun is the cause of the generation of all men; whereas the univocal agent is not the universal efficient cause of the whole species (otherwise it would be the cause of itself, since it is contained in the species), but is a particular cause of this individual which it places under the species by way of participation. Therefore the universal cause of the whole species is not an univocal agent; and the universal cause comes before the particular cause. But this universal agent, whilst it is not univocal, nevertheless is not altogether equivocal, otherwise it could not produce its own likeness, but rather it is to be called an analogical agent, as all univocal predications are reduced to one first non-univocal analogical predication, which is being."

If substance is the highest category and there is no substance, being, then the unity perceived in all beings by virtue of their existing must be viewed in another way. St. Thomas chose the analogy: all beings are like, or analogous to, each other in existing. This comparison is the basis of his Analogy of Being. The analogy is said of being in many different ways, but the key to it is the real distinction between existence and essence. Existence is the principle that gives reality to an essence not the same in any way as the existence: "If things having essences are real, and it is not of their essence to be, then the reality of these things must be found in some principle other than (really distinct from) their essence." Substance can be real or not. What makes an individual substance – a man, a tree, a planet – real is a distinct act, a "to be", which actuates its unity. An analogy of proportion is therefore possible: "essence is related to existence as potency is related to act."

Existences are not things; they do not themselves exist, they lend themselves to essences, which do not intrinsically have them. They have no nature; an existence receives its nature from the essence it actuates. Existence is not being; it gives being – here a customary phrase is used, existence is a principle (a source) of being, not a previous source, but one which is continually in effect. The stage is set for the concept of God as the cause of all existence, who, as the Almighty, holds everything actual without reason or explanation as an act purely of will.

The transcendentals

Aristotle's classificatory scheme had included the five predicables, or characteristics that might be predicated of a substance. One of these was the property, an essential universal true of the species, but not in the definition (in modern terms, some examples would be grammatical language, a property of man, or a spectral pattern characteristic of an element, both of which are defined in other ways). Pointing out that predicables are predicated univocally of substances; that is, they refer to "the same thing" found in each instance, St. Thomas argued that whatever can be said about being is not univocal, because all beings are unique, each actuated by a unique existence. It is the analogous possession of an existence that allows them to be identified as being; therefore, being is an analogous predication.Whatever can be predicated of all things is universal-like but not universal, category-like but not a category. St. Thomas called them (perhaps not originally) the transcendentia, "transcendentals", because they "climb above" the categories, just as being climbs above substance. Later academics also referred to them as "the properties of being." The number is generally three or four.

Being in Islamic philosophy

The nature of "being" has also been debated and explored in Islamic philosophy, notably by Ibn Sina (Avicenna), Suhrawardi, and Mulla Sadra.A modern linguistic approach which notices that Persian language has exceptionally developed two kinds of "is"es, i.e. ast ("is", as a copula) and hast (as an existential "is") examines the linguistic properties of the two lexemes in the first place, then evaluates how the statements made by other languages with regard to being can stand the test of Persian frame of reference.

In this modern linguistic approach, it is noticed that the original language of the source, e.g. Greek (like German or French or English), has only one word for two concepts, ast and hast, or, like Arabic, has no word at all for either word. It therefore exploits the Persian hast (existential is) versus ast (predicative is or copula) to address both Western and Islamic ontological arguments on being and existence.

This linguistic method shows the scope of confusion created by languages which cannot differentiate between existential be and copula. It manifests, for instance, that the main theme of Heidegger's Being and Time is astī (is-ness) rather than hastī (existence). When, in the beginning of his book, Heidegger claims that people always talk about existence in their everyday language, without knowing what it means, the example he resorts to is: "the sky is blue" which in Persian can be ONLY translated with the use of the copula ast, and says nothing about being or existence.

In the same manner, the linguistic method addresses the ontological works written in Arabic. Since Arabic, like Latin in Europe, had become the official language of philosophical and scientific works in the so-called Islamic World, the early Persian or Arab philosophers had difficulty discussing being or existence, since the Arabic language, like other Semitic languages, had no verb for either predicative "be" (copula) or existential "be". So if you try to translate the aforementioned Heidegger's example into Arabic it appears as السماء زرقاء (viz. "The Sky-- blue") with no linking "is" to be a sign of existential statement. To overcome the problem, when translating the ancient Greek philosophy, certain words were coined like ایس aysa (from Arabic لیس laysa 'not') for 'is'. Eventually the Arabic verb وجد wajada (to find) prevailed, since it was thought that whatever is existent, is to be "found" in the world. Hence existence or Being was called وجود wujud (Cf. Swedish finns [found]> there exist; also the Medieval Latin coinage of exsistere 'standing out (there in the world)' > appear> exist).

Now, with regard to the fact that Persian, as the mother tongue of both Avicenna and Sadrā, was in conflict with either Greek or Arabic in this regard, these philosophers should have been warned implicitly by their mother tongue not to confuse two kinds of linguistic beings (viz. copula vs. existential). In fact when analyzed thoroughly, copula, or Persian ast ('is') indicates an ever-moving chain of relations with no fixed entity to hold onto (every entity, say A, will be dissolved into "A is B" and so on, as soon as one tries to define it). Therefore, the whole reality or what we see as existence ("found" in our world) resembles an ever-changing world of astī (is-ness) flowing in time and space. On the other hand, while Persian ast can be considered as the 3rd person singular of the verb 'to be', there is no verb but an arbitrary one supporting hast ('is' as an existential be= exists) has neither future nor past tense and nor a negative form of its own: hast is just a single untouchable lexeme. It needs no other linguistic element to be complete (Hast. is a complete sentence meaning "s/he it exists"). In fact, any manipulation of the arbitrary verb, e.g. its conjugation, turns hast back into a copula.

Eventually from such linguistic analyses, it appears that while astī (is-ness) would resemble the world of Heraclitus, hastī (existence) would rather approaches a metaphysical concept resembling the Parmenidas's interpretation of existence.

In this regard, Avicenna, who was a firm follower of Aristotle, could not accept either Heraclitian is-ness (where only constant was change), nor Parmenidean monist immoveable existence (the hastī itself being constant). To solve the contradiction, it so appeared to Philosophers of Islamic world that Aristotle considered the core of existence (i.e. its substance/essence) as a fixed constant, while its facade (accident) was prone to change. To translate such a philosophical image into Persian it is like having hastī (existence) as a unique constant core covered by astī (is-ness) as a cloud of ever-changing relationships. It is clear that the Persian language, deconstructs such a composite as a sheer mirage, since it is not clear how to link the interior core (existence) with the exterior shell (is-ness). Furthermore, hast cannot be linked to anything but itself (as it is self-referent).

The argument has a theological echos as well: assuming that God is the Existence, beyond time and space, a question is raised by philosophers of the Islamic world as how he, as a transcendental existence, may ever create or contact a world of is-ness in space-time.

However, Avicenna who was more philosopher than theologian, followed the same line of argumentation as that of his ancient master, Aristotle, and tried to reconcile between ast and hast, by considering the latter as higher order of existence than the former. It is like a hierarchical order of existence. It was a philosophical Tower of Babel that the restriction of his own mother tongue (Persian) would not allow to be built, but he could maneuver in Arabic by giving the two concepts the same name wujud, although with different attributes. So, implicitly, astī (is-ness) appears as ممکن الوجود "momken-al-wujud" (contingent being), and hastī (existence) as واجب الوجود "wājeb-al-wujud" (necessary being).

On the other hand, centuries later, Sadrā, chose a more radical route, by inclining towards the reality of astī (is-ness), as the true mode of existence, and tried to get rid of the concept of hastī (existence as fixed or immovable). Thus, in his philosophy, the universal movement penetrates deep into the Aristotelian substance/essence, in unison with changing accident. He called this deep existential change حرکت جوهری harekat-e jowhari (Substantial Movement). In such a changing existence, the whole world has to go through instantaneous annihilation and recreation incessantly, while as Avicenna had predicted in his remarks on Nature, such a universal change or substantial movement would eventually entail the shortening and lengthening of time as well which has never been observed. This logical objection, which was made on Aristotle's argumentation, could not be answered in the ancient times or medieval age, but now it does not sound contradictory to the real nature of Time (as addressed in relativity theory), so by a reverse argument, a philosopher may indeed deduce that everything is changing (moving) even in the deepest core of Being.

Being in the Age of Reason

Although innovated in the late medieval period, Thomism was dogmatized in the Renaissance. From roughly 1277 to 1567, it dominated the philosophic landscape. The rationalist philosophers, however, with a new emphasis on Reason as a tool of the intellect, brought the classical and medieval traditions under new scrutiny, exercising a new concept of doubt, with varying outcomes. Foremost among the new doubters were the empiricists, the advocates of scientific method, with its emphasis on experimentation and reliance on evidence gathered from sensory experience. In parallel with the revolutions against rising political absolutism based on established religion and the replacement of faith by reasonable faith, new systems of metaphysics were promulgated in the lecture halls by charismatic professors, such as Immanuel Kant, and Hegel. The late 19th and 20th centuries featured an emotional return to the concept of existence under the name of existentialism. These philosophers were concerned mainly with ethics and religion. The metaphysical side became the domain of the phenomenalists. In parallel with these philosophies Thomism continued under the protection of the Catholic Church; in particular, the Jesuit order.Empiricist doubts

Rationalism and empiricism have had many definitions, most concerned with specific schools of philosophy or groups of philosophers in particular countries, such as Germany. In general rationalism is the predominant school of thought in the multi-national, cross-cultural Age of reason, which began in the century straddling 1600 as a conventional date, empiricism is the reliance on sensory data gathered in experimentation by scientists of any country, who, in the Age of Reason were rationalists. An early professed empiricist, Thomas Hobbes, known as an eccentric denizen of the court of Charles II of England (an "old bear"), published in 1651 Leviathan, a political treatise written during the English civil war, containing an early manifesto in English of rationalism.Hobbes said:

"The Latines called Accounts of mony Rationes ... and thence it seems to proceed that they extended the word Ratio, to the faculty of Reckoning in all other things....When a man reasoneth hee does nothing else but conceive a summe totall ... For Reason ... is nothing but Reckoning ... of the consequences of generall names agreed upon, for the marking and signifying of our thoughts ...."In Hobbes reasoning is the right process of drawing conclusions from definitions (the "names agreed upon"). He goes on to define error as self-contradiction of definition ("an absurdity, or senselesse Speech") or conclusions that do not follow the definitions on which they are supposed to be based. Science, on the other hand, is the outcome of "right reasoning," which is based on "natural sense and imagination", a kind of sensitivity to nature, as "nature it selfe cannot erre."

Having chosen his ground carefully Hobbes launches an epistemological attack on metaphysics. The academic philosophers had arrived at the Theory of Matter and Form from consideration of certain natural paradoxes subsumed under the general heading of the Unity Problem. For example, a body appears to be one thing and yet it is distributed into many parts. Which is it, one or many? Aristotle had arrived at the real distinction between matter and form, metaphysical components whose interpenetration produces the paradox. The whole unity comes from the substantial form and the distribution into parts from the matter. Inhering in the parts giving them really distinct unities are the accidental forms. The unity of the whole being is actuated by another really distinct principle, the existence.

If nature cannot err, then there are no paradoxes in it; to Hobbes, the paradox is a form of the absurd, which is inconsistency: "Natural sense and imagination, are not subject to absurdity" and "For error is but a deception ... But when we make a generall assertion, unlesse it be a true one, the possibility of it is inconceivable. And words whereby we conceive nothing but the sound, are those we call Absurd ...." Among Hobbes examples are "round quadrangle", "immaterial substance", "free subject." Of the scholastics he says:

"Yet they will have us beleeve, that by the Almighty power of God, one body may be at one and the same time in many places [the problem of the universals]; and many bodies at one and the same time in one place [the whole and the parts]; ... And these are but a small part of the Incongruencies they are forced to, from their disputing philosophically, instead of admiring, and adoring of the Divine and Incomprehensible Nature ...."The real distinction between essence and existence, and that between form and matter, which served for so long as the basis of metaphysics, Hobbes identifies as "the Error of Separated Essences." The words "Is, or Bee, or Are, and the like" add no meaning to an argument nor do derived words such as "Entity, Essence, Essentially, Essentiality", which "are the names of nothing" but are mere "Signes" connecting "one name or attribute to another: as when we say, "a man is a living body", we mean not that the man is one thing, the living body another, and the is, or being a third: but that the man, and the living body, is the same thing; ..." Metaphysiques, Hobbes says, is "far from the possibility of being understood" and is "repugnant to natural reason."

Being to Hobbes (and the other empiricists) is the physical universe:

The world, (I mean ... the Universe, that is, the whole masse of all things that are) is corporeall, that is to say, Body; and hath the dimension of magnitude, namely, Length, Bredth and Depth: also every part of Body, is likewise Body ... and consequently every part of the Universe is Body, and that which is not Body, is no part of the Universe: and because the Universe is all, that which is no part of it is nothing; and consequently no where."Hobbes' view is representative of his tradition. As Aristotle offered the categories and the act of existence, and Aquinas the analogy of being, the rationalists also had their own system, the great chain of being, an interlocking hierarchy of beings from God to dust.

Idealist systems

In addition to the materialism of the empiricists, under the same aegis of Reason, rationalism produced systems that were diametrically opposed now called idealism, which denied the reality of matter in favor of the reality of mind. By a 20th-century classification, the idealists (Kant, Hegel and others), are considered the beginning of continental philosophy, while the empiricists are the beginning, or the immediate predecessors, of analytical philosophy.Being in continental philosophy and existentialism

Some philosophers deny that the concept of "being" has any meaning at all, since we only define an object's existence by its relation to other objects, and actions it undertakes. The term "I am" has no meaning by itself; it must have an action or relation appended to it. This in turn has led to the thought that "being" and nothingness are closely related, developed in existential philosophy.Existentialist philosophers such as Sartre, as well as continental philosophers such as Hegel and Heidegger have also written extensively on the concept of being. Hegel distinguishes between the being of objects (being in itself) and the being of people (Geist). Hegel, however, did not think there was much hope for delineating a "meaning" of being, because being stripped of all predicates is simply nothing.

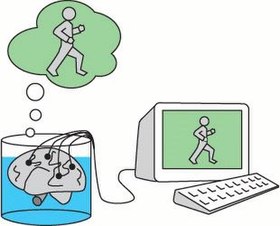

Heidegger, in his quest to re-pose the original pre-Socratic question of Being, wondered at how to meaningfully ask the question of the meaning of being, since it is both the greatest, as it includes everything that is, and the least, since no particular thing can be said of it. He distinguishes between different modes of beings: a privative mode is present-at-hand, whereas beings in a fuller sense are described as ready-to-hand. The one who asks the question of Being is described as Da-sein ("there/here-being") or being-in-the-world. Sartre, popularly understood as misreading Heidegger (an understanding supported by Heidegger's essay "Letter on Humanism" which responds to Sartre's famous address, "Existentialism is a Humanism"), employs modes of being in an attempt to ground his concept of freedom ontologically by distinguishing between being-in-itself and being-for-itself.

Being is also understood as one's "state of being," and hence its common meaning is in the context of human (personal) experience, with aspects that involve expressions and manifestations coming from an innate "being", or personal character. Heidegger coined the term "dasein" for this property of being in his influential work Being and Time ("this entity which each of us is himself…we shall denote by the term 'dasein.'"), in which he argued that being or dasein links one's sense of one's body to one's perception of world. Heidegger, amongst others, referred to an innate language as the foundation of being, which gives signal to all aspects of being.