People beginning in the mid 20th century have used the term Counter-Enlightenment to describe strains of thought that arose in the late 18th and early 19th centuries in opposition to the 18th-century Enlightenment.

Although the first known use of the term in English occurred in 1949 and there were several earlier uses of it, including one by German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche, the term "Counter-Enlightenment" is usually associated with Isaiah Berlin, who is often credited for re-inventing it. Discussion of this concept began with Isaiah Berlin's 1973 Essay, The Counter-Enlightenment. He published widely about the Enlightenment and its challengers and did much to popularise the concept of a Counter-Enlightenment movement that he characterized as relativist, anti-rationalist, vitalist, and organic, which he associated most closely with German Romanticism.

Development and significant people

Early stages

Despite criticism of the Enlightenment being a widely discussed topic in twentieth-century thought, the term 'Counter-Enlightenment' was underdeveloped. It was first mentioned briefly in English in William Barrett's 1949 article "Art, Aristocracy and Reason" in Partisan Review. He used the term again in his 1958 book on existentialism, Irrational Man; however, his comment on Enlightenment criticism was very limited. In Germany, the expression "Gegen-Aufklärung" has a longer history. It was probably coined by Friedrich Nietzsche in "Nachgelassene Fragmente" in 1877.

Lewis White Beck used this term in his Early German Philosophy (1969), a book about Counter-Enlightenment in Germany. Beck claims that there is a counter-movement arising in Germany in reaction to Frederick II's secular authoritarian state. On the other hand, Johann Georg Hamann and his fellow philosophers believe that a more organic conception of social and political life, a more vitalistic view of nature, and an appreciation for beauty and the spiritual life of man have been neglected by the eighteenth century.

Isaiah Berlin

Isaiah Berlin established this term's place in the history of ideas. He used it to refer to a movement that arose primarily in late 18th- and early 19th-century Germany against the rationalism, universalism and empiricism, which are commonly associated with the Enlightenment. Berlin's essay "The Counter-Enlightenment" was first published in 1973, and later reprinted in a collection of his works, Against the Current, in 1981. The term has been more widely used since.

Berlin argues that, while there were opponents of the Enlightenment outside of Germany (e.g. Joseph de Maistre) and before the 1770s (e.g. Giambattista Vico), Counter-Enlightenment thought did not start until the Germans 'rebelled against the dead hand of France in the realms of culture, art and philosophy, and avenged themselves by launching the great counter-attack against the Enlightenment.' This German reaction to the imperialistic universalism of the French Enlightenment and Revolution, which had been forced on them first by the francophile Frederick II of Prussia, then by the armies of Revolutionary France and finally by Napoleon, was crucial to the shift of consciousness that occurred in Europe at this time, leading eventually to Romanticism. The consequence of this revolt against the Enlightenment was pluralism. The opponents to the Enlightenment played a more crucial role than its proponents, some of whom were monists, whose political, intellectual and ideological offspring have been terreur and totalitarianism.

Darrin McMahon

In his book Enemies of the Enlightenment (2001), historian Darrin McMahon extends the Counter-Enlightenment back to pre-Revolutionary France and down to the level of 'Grub Street,' thereby marking a major advance on Berlin's intellectual and Germanocentric view. McMahon focuses on the early opponents to the Enlightenment in France, unearthing a long-forgotten 'Grub Street' literature in the late 18th and early 19th centuries aimed at the philosophes. He delves into the obscure world of the 'low Counter-Enlightenment' that attacked the encyclopédistes and fought to prevent the dissemination of Enlightenment ideas in the second half of the century. Many people from earlier times attacked the Enlightenment for undermining religion and the social and political order. It later became a major theme of conservative criticism of the Enlightenment. After the French Revolution, it appeared to vindicate the warnings of the anti-philosophes in the decades prior to 1789.

Graeme Garrard

Cardiff University professor Graeme Garrard claims that historian William R. Everdell was the first to situate Rousseau as the "founder of the Counter-Enlightenment" in his 1971 dissertation and in his 1987 book, Christian Apologetics in France, 1730–1790: The Roots of Romantic Religion. In his 1996 article, "the Origin of the Counter-Enlightenment: Rousseau and the New Religion of Sincerity", in the American Political Science Review (Vol. 90, No. 2), Arthur M. Melzer corroborates Everdell's view in placing the origin of the Counter-Enlightenment in the religious writings of Jean-Jacques Rousseau, further showing Rousseau as the man who fired the first shot in the war between the Enlightenment and its opponents. Graeme Garrard follows Melzer in his "Rousseau's Counter-Enlightenment" (2003). This contradicts Berlin's depiction of Rousseau as a philosophe (albeit an erratic one) who shared the basic beliefs of his Enlightenment contemporaries. But similar to McMahon, Garrard traces the beginning of Counter-Enlightenment thought back to France and prior to the German Sturm und Drang movement of the 1770s. Garrard's book Counter-Enlightenments (2006) broadens the term even further, arguing against Berlin that there was no single 'movement' called 'The Counter-Enlightenment'. Rather, there have been many Counter-Enlightenments, from the middle of the 18th century to 20th-century Enlightenment among critical theorists, postmodernists and feminists. The Enlightenment has opponents on all points of its ideological compass, from the far left to the far right, and all points in between. Each of the Enlightenment's challengers depicted it as they saw it or wanted others to see it, resulting in a vast range of portraits, many of which are not only different but incompatible.

James Schmidt

The idea of Counter-Enlightenment has evolved in the following years. The historian James Schmidt questioned the idea of 'Enlightenment' and therefore of the existence of a movement opposing it. As the conception of 'Enlightenment' has become more complex and difficult to maintain, so has the idea of the 'Counter-Enlightenment'. Advances in Enlightenment scholarship in the last quarter-century have challenged the stereotypical view of the 18th century as an 'Age of Reason', leading Schmidt to speculate on whether the Enlightenment might not actually be a creation of its opponents, but the other way round. The fact that the term 'Enlightenment' was first used in 1894 in English to refer to a historical period supports the argument that it was a late construction projected back onto the 18th century.

The French Revolution

By the mid-1790s, the Reign of Terror during the French Revolution fueled a major reaction against the Enlightenment. Many leaders of the French Revolution and their supporters made Voltaire and Rousseau, as well as Marquis de Condorcet's ideas of reason, progress, anti-clericalism, and emancipation central themes to their movement. It led to an unavoidable backlash to the Enlightenment as there were people opposed to the revolution. Many counter-revolutionary writers, such as Edmund Burke, Joseph de Maistre and Augustin Barruel, asserted an intrinsic link between the Enlightenment and the Revolution. They blamed the Enlightenment for undermining traditional beliefs that sustained the ancien regime. As the Revolution became increasingly bloody, the idea of 'Enlightenment' was discredited, too. Hence, the French Revolution and its aftermath have contributed to the development of Counter-Enlightenment thought.

Edmund Burke was among the first of the Revolution's opponents to relate the philosophes to the instability in France in the 1790s. His Reflections on the Revolution in France (1790) refers the Enlightenment as the principal cause of the French revolution. In Burke's opinion, the philosophes provided the revolutionary leaders with the theories on which their political schemes were based.

Augustin Barruel's Counter-Enlightenment ideas were well developed before the revolution. He worked as an editor for the anti-philosophes literary journal, L'Année Littéraire. Barruel argues in his Memoirs Illustrating the History of Jacobinism (1797) that the Revolution was the consequence of a conspiracy of philosophes and freemasons.

In Considerations on France (1797), Joseph de Maistre interprets the Revolution as divine punishment for the sins of the Enlightenment. According to him, "the revolutionary storm is an overwhelming force of nature unleashed on Europe by God that mocked human pretensions."

Romanticism

In the 1770s, the 'Sturm und Drang' movement started in Germany. It questioned some key assumptions and implications of the Aufklärung and the term 'Romanticism' was first coined. Many early Romantic writers such as Chateaubriand, Federich von Hardenberg (Novalis) and Samuel Taylor Coleridge inherited the Counter-Revolutionary antipathy towards the philosophes. All three directly blamed the philosophes in France and the Aufklärer

in Germany for devaluing beauty, spirit and history in favour of a view

of man as a soulless machine and a view of the universe as a

meaningless, disenchanted void lacking richness and beauty. One

particular concern to early Romantic writers was the allegedly

anti-religious nature of the Enlightenment since the philosophes and Aufklarer were generally deists, opposed to revealed religion. Some historians, such as Hamann,

nevertheless contend that this view of the Enlightenment as an age

hostile to religion is common ground between these Romantic writers and

many of their conservative Counter-Revolutionary predecessors. However,

not many have commented on the Enlightenment, except for Chateaubriand,

Novalis, and Coleridge, since the term itself did not exist at the time

and most of their contemporaries ignored it.

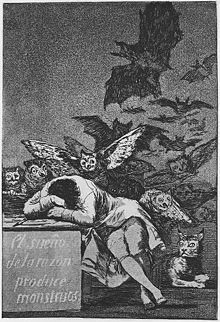

The historian Jacques Barzun argues that Romanticism has its roots in the Enlightenment. It was not anti-rational, but rather balanced rationality against the competing claims of intuition and the sense of justice. This view is expressed in Goya's Sleep of Reason, in which the nightmarish owl offers the dozing social critic of Los Caprichos, a piece of drawing chalk. Even the rational critic is inspired by irrational dream-content under the gaze of the sharp-eyed lynx. Marshall Brown makes much the same argument as Barzun in Romanticism and Enlightenment, questioning the stark opposition between these two periods.

By the middle of the 19th century, the memory of the French Revolution was fading and so was the influence of Romanticism. In this optimistic age of science and industry, there were few critics of the Enlightenment, and few explicit defenders. Friedrich Nietzsche is a notable and highly influential exception. After an initial defence of the Enlightenment in his so-called 'middle period' (late-1870s to early 1880s), Nietzsche turned vehemently against it.

Totalitarianism

In the intellectual discourse of the mid-20th century, two concepts emerged simultaneously in the West: enlightenment and totalitarianism. After World War II, the former re-emerged as a key organizing concept in social and political thought and the history of ideas. The Counter-Enlightenment literature blaming the 18th-century trust in reason for 20th-century totalitarianism also resurged along with it. The locus classicus of this view is Max Horkheimer and Theodor Adorno's Dialectic of Enlightenment (1947), which traces the degeneration of the general concept of enlightenment from ancient Greece (epitomized by the cunning 'bourgeois' hero Odysseus) to 20th-century fascism. They mentioned little about Soviet communism, only referring to it as a regressive totalitarianism that "clung all too desperately to the heritage of bourgeois philosophy".

The authors take 'enlightenment' as their target including its 18th-century form – which we now call 'The Enlightenment'. They claim it is epitomized by the Marquis de Sade. However, there were philosophers rejecting Adorno and Horkheimer's claim that Sade's moral skepticism is actually coherent, or that it reflects Enlightenment thought.

Many postmodern writers and feminists (e.g. Jane Flax) have made similar arguments. They regard the Enlightenment conception of reason as totalitarian, and as not having been enlightened enough since. For Adorno and Horkheimer, though it banishes myth it falls back into a further myth, that of individualism and formal (or mythic) equality under instrumental reason.

Michel Foucault, for example, argued that attitudes towards the "insane" during the late-18th and early 19th centuries show that supposedly enlightened notions of humane treatment were not universally adhered to, but instead, the Age of Reason had to construct an image of "Unreason" against which to take an opposing stand. Berlin himself, although no postmodernist, argues that the Enlightenment's legacy in the 20th century has been monism (which he claims favours political authoritarianism), whereas the legacy of the Counter-Enlightenment has been pluralism (associates with liberalism). These are two of the 'strange reversals' of modern intellectual history.