The history of molecular biology begins in the 1930s with the convergence of various, previously distinct biological and physical disciplines: biochemistry, genetics, microbiology, virology and physics. With the hope of understanding life at its most fundamental level, numerous physicists and chemists also took an interest in what would become molecular biology.

In its modern sense, molecular biology attempts to explain the phenomena of life starting from the macromolecular properties that generate them. Two categories of macromolecules in particular are the focus of the molecular biologist: 1) nucleic acids, among which the most famous is deoxyribonucleic acid (or DNA), the constituent of genes, and 2) proteins, which are the active agents of living organisms. One definition of the scope of molecular biology therefore is to characterize the structure, function and relationships between these two types of macromolecules. This relatively limited definition allows for the estimation of a date for the so-called "molecular revolution", or at least to establish a chronology of its most fundamental developments.

General overview

In its earliest manifestations, molecular biology—the name was coined by Warren Weaver of the Rockefeller Foundation in 1938—was an idea of physical and chemical explanations of life, rather than a coherent discipline. Following the advent of the Mendelian-chromosome theory of heredity in the 1910s and the maturation of atomic theory and quantum mechanics in the 1920s, such explanations seemed within reach. Weaver and others encouraged (and funded) research at the intersection of biology, chemistry and physics, while prominent physicists such as Niels Bohr and Erwin Schrödinger turned their attention to biological speculation. However, in the 1930s and 1940s it was by no means clear which—if any—cross-disciplinary research would bear fruit; work in colloid chemistry, biophysics and radiation biology, crystallography, and other emerging fields all seemed promising.

In 1940, George Beadle and Edward Tatum demonstrated the existence of a precise relationship between genes and proteins. In the course of their experiments connecting genetics with biochemistry, they switched from the genetics mainstay Drosophila to a more appropriate model organism, the fungus Neurospora; the construction and exploitation of new model organisms would become a recurring theme in the development of molecular biology. In 1944, Oswald Avery, working at the Rockefeller Institute of New York, demonstrated that genes are made up of DNA (see Avery–MacLeod–McCarty experiment). In 1952, Alfred Hershey and Martha Chase confirmed that the genetic material of the bacteriophage, the virus which infects bacteria, is made up of DNA (see Hershey–Chase experiment). In 1953, James Watson and Francis Crick discovered the double helical structure of the DNA molecule based on the discoveries made by Rosalind Franklin. In 1961, François Jacob and Jacques Monod demonstrated that the products of certain genes regulated the expression of other genes by acting upon specific sites at the edge of those genes. They also hypothesized the existence of an intermediary between DNA and its protein products, which they called messenger RNA. Between 1961 and 1965, the relationship between the information contained in DNA and the structure of proteins was determined: there is a code, the genetic code, which creates a correspondence between the succession of nucleotides in the DNA sequence and a series of amino acids in proteins.

In April 2023, scientists, based on new evidence, concluded that Rosalind Franklin was a contributor and "equal player" in the discovery process of DNA, rather than otherwise, as may have been presented subsequently after the time of the discovery.

The chief discoveries of molecular biology took place in a period of only about twenty-five years. Another fifteen years were required before new and more sophisticated technologies, united today under the name of genetic engineering, would permit the isolation and characterization of genes, in particular those of highly complex organisms.

The exploration of the molecular dominion

If we evaluate the molecular revolution within the context of biological history, it is easy to note that it is the culmination of a long process which began with the first observations through a microscope. The aim of these early researchers was to understand the functioning of living organisms by describing their organization at the microscopic level. From the end of the 18th century, the characterization of the chemical molecules which make up living beings gained increasingly greater attention, along with the birth of physiological chemistry in the 19th century, developed by the German chemist Justus von Liebig and following the birth of biochemistry at the beginning of the 20th, thanks to another German chemist Eduard Buchner. Between the molecules studied by chemists and the tiny structures visible under the optical microscope, such as the cellular nucleus or the chromosomes, there was an obscure zone, "the world of the ignored dimensions," as it was called by the chemical-physicist Wolfgang Ostwald. This world is populated by colloids, chemical compounds whose structure and properties were not well defined.

The successes of molecular biology derived from the exploration of that unknown world by means of the new technologies developed by chemists and physicists: X-ray diffraction, electron microscopy, ultracentrifugation, and electrophoresis. These studies revealed the structure and function of the macromolecules.

A milestone in that process was the work of Linus Pauling in 1949, which for the first time linked the specific genetic mutation in patients with sickle cell disease to a demonstrated change in an individual protein, the hemoglobin in the erythrocytes of heterozygous or homozygous individuals.

The encounter between biochemistry and genetics

The development of molecular biology is also the encounter of two disciplines which made considerable progress in the course of the first thirty years of the twentieth century: biochemistry and genetics. The first studies the structure and function of the molecules which make up living things. Between 1900 and 1940, the central processes of metabolism were described: the process of digestion and the absorption of the nutritive elements derived from alimentation, such as the sugars. Every one of these processes is catalyzed by a particular enzyme. Enzymes are proteins, like the antibodies present in blood or the proteins responsible for muscular contraction. As a consequence, the study of proteins, of their structure and synthesis, became one of the principal objectives of biochemists.

The second discipline of biology which developed at the beginning of the 20th century is genetics. After the rediscovery of the laws of Mendel through the studies of Hugo de Vries, Carl Correns and Erich von Tschermak in 1900, this science began to take shape thanks to the adoption by Thomas Hunt Morgan, in 1910, of a model organism for genetic studies, the famous fruit fly (Drosophila melanogaster). Shortly after, Morgan showed that the genes are localized on chromosomes. Following this discovery, he continued working with Drosophila and, along with numerous other research groups, confirmed the importance of the gene in the life and development of organisms. Nevertheless, the chemical nature of genes and their mechanisms of action remained a mystery. Molecular biologists committed themselves to the determination of the structure, and the description of the complex relations between, genes and proteins.

The development of molecular biology was not just the fruit of some sort of intrinsic "necessity" in the history of ideas, but was a characteristically historical phenomenon, with all of its unknowns, imponderables and contingencies: the remarkable developments in physics at the beginning of the 20th century highlighted the relative lateness in development in biology, which became the "new frontier" in the search for knowledge about the empirical world. Moreover, the developments of the theory of information and cybernetics in the 1940s, in response to military exigencies, brought to the new biology a significant number of fertile ideas and, especially, metaphors.

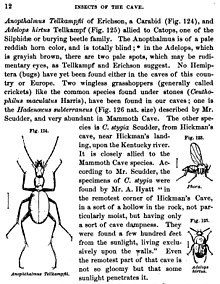

The choice of bacteria and of its virus, the bacteriophage, as models for the study of the fundamental mechanisms of life was almost natural—they are the smallest living organisms known to exist—and at the same time the fruit of individual choices. This model owes its success, above all, to the fame and the sense of organization of Max Delbrück, a German physicist, who was able to create a dynamic research group, based in the United States, whose exclusive scope was the study of the bacteriophage: the phage group.

The phage group was an informal network of biologists that carried out basic research mainly on bacteriophage T4 and made numerous seminal contributions to microbial genetics and the origins of molecular biology in the mid-20th century. In 1961, Sydney Brenner, an early member of the phage group, collaborated with Francis Crick, Leslie Barnett and Richard Watts-Tobin at the Cavendish Laboratory in Cambridge to perform genetic experiments that demonstrated the basic nature of the genetic code for proteins. These experiments, carried out with mutants of the rIIB gene of bacteriophage T4, showed, that for a gene that encodes a protein, three sequential bases of the gene's DNA specify each successive amino acid of the protein. Thus the genetic code is a triplet code, where each triplet (called a codon) specifies a particular amino acid. They also found that the codons do not overlap with each other in the DNA sequence encoding a protein, and that such a sequence is read from a fixed starting point. During 1962–1964 phage T4 researchers provided an opportunity to study the function of virtually all of the genes that are essential for growth of the bacteriophage under laboratory conditions. These studies were facilitated by the discovery of two classes of conditional lethal mutants. One class of such mutants is known as amber mutants. Another class of conditional lethal mutants is referred to as temperature-sensitive mutants. Studies of these two classes of mutants led to considerable insight into numerous fundamental biologic problems. Thus understanding was gained on the functions and interactions of the proteins employed in the machinery of DNA replication, DNA repair and DNA recombination. Furthermore, understanding was gained on the processes by which viruses are assembled from protein and nucleic acid components (molecular morphogenesis). Also, the role of chain terminating codons was elucidated. One noteworthy study used amber mutants defective in the gene encoding the major head protein of bacteriophage T4. This experiment provided strong evidence for the widely held, but prior to 1964 still unproven, "sequence hypothesis" that the amino acid sequence of a protein is specified by the nucleotide sequence of the gene determining the protein. Thus, this study demonstrated the co-linearity of the gene with its encoded protein.

The geographic panorama of the developments of the new biology was conditioned above all by preceding work. The US, where genetics had developed the most rapidly, and the UK, where there was a coexistence of both genetics and biochemical research of highly advanced levels, were in the avant-garde. Germany, the cradle of the revolutions in physics, with the best minds and the most advanced laboratories of genetics in the world, should have had a primary role in the development of molecular biology. But history decided differently: the arrival of the Nazis in 1933—and, to a less extreme degree, the rigidification of totalitarian measures in fascist Italy—caused the emigration of a large number of Jewish and non-Jewish scientists. The majority of them fled to the US or the UK, providing an extra impulse to the scientific dynamism of those nations. These movements ultimately made molecular biology a truly international science from the very beginnings.

History of DNA biochemistry

First isolation of DNA

Working in the 19th century, biochemists initially isolated DNA and RNA (mixed together) from cell nuclei. They were relatively quick to appreciate the polymeric nature of their "nucleic acid" isolates, but realized only later that nucleotides were of two types—one containing ribose and the other deoxyribose. It was this subsequent discovery that led to the identification and naming of DNA as a substance distinct from RNA.

Friedrich Miescher (1844–1895) discovered a substance he called "nuclein" in 1869. Somewhat later, he isolated a pure sample of the material now known as DNA from the sperm of salmon, and in 1889 his pupil, Richard Altmann, named it "nucleic acid". This substance was found to exist only in the chromosomes.

In 1919 Phoebus Levene at the Rockefeller Institute identified the components (the four bases, the sugar and the phosphate chain) and he showed that the components of DNA were linked in the order phosphate-sugar-base. He called each of these units a nucleotide and suggested the DNA molecule consisted of a string of nucleotide units linked together through the phosphate groups, which are the 'backbone' of the molecule. However Levene thought the chain was short and that the bases repeated in the same fixed order. Torbjörn Caspersson and Einar Hammersten showed that DNA was a polymer.

Chromosomes and inherited traits

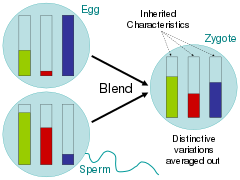

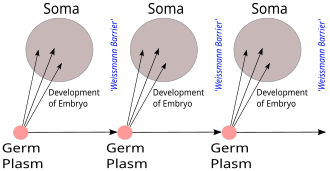

In 1927, Nikolai Koltsov proposed that inherited traits would be inherited via a "giant hereditary molecule" which would be made up of "two mirror strands that would replicate in a semi-conservative fashion using each strand as a template". Max Delbrück, Nikolay Timofeev-Ressovsky, and Karl G. Zimmer published results in 1935 suggesting that chromosomes are very large molecules the structure of which can be changed by treatment with X-rays, and that by so changing their structure it was possible to change the heritable characteristics governed by those chromosomes. In 1937 William Astbury produced the first X-ray diffraction patterns from DNA. He was not able to propose the correct structure but the patterns showed that DNA had a regular structure and therefore it might be possible to deduce what this structure was.

In 1943, Oswald Theodore Avery and a team of scientists discovered that traits proper to the "smooth" form of the Pneumococcus could be transferred to the "rough" form of the same bacteria merely by making the killed "smooth" (S) form available to the live "rough" (R) form. Quite unexpectedly, the living R Pneumococcus bacteria were transformed into a new strain of the S form, and the transferred S characteristics turned out to be heritable. Avery called the medium of transfer of traits the transforming principle; he identified DNA as the transforming principle, and not protein as previously thought. He essentially redid Frederick Griffith's experiment. In 1953, Alfred Hershey and Martha Chase did an experiment (Hershey–Chase experiment) that showed, in T2 phage, that DNA is the genetic material (Hershey shared the Nobel prize with Luria).

Discovery of the structure of DNA

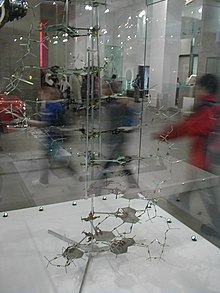

In the 1950s, three groups made it their goal to determine the structure of DNA. The first group to start was at King's College London and was led by Maurice Wilkins and was later joined by Rosalind Franklin. Another group consisting of Francis Crick and James Watson was at Cambridge. A third group was at Caltech and was led by Linus Pauling. Crick and Watson built physical models using metal rods and balls, in which they incorporated the known chemical structures of the nucleotides, as well as the known position of the linkages joining one nucleotide to the next along the polymer. At King's College Maurice Wilkins and Rosalind Franklin examined X-ray diffraction patterns of DNA fibers. Of the three groups, only the London group was able to produce good quality diffraction patterns and thus produce sufficient quantitative data about the structure.

Helix structure

In 1948, Pauling discovered that many proteins included helical (see alpha helix) shapes. Pauling had deduced this structure from X-ray patterns and from attempts to physically model the structures. (Pauling was also later to suggest an incorrect three chain helical DNA structure based on Astbury's data.) Even in the initial diffraction data from DNA by Maurice Wilkins, it was evident that the structure involved helices. But this insight was only a beginning. There remained the questions of how many strands came together, whether this number was the same for every helix, whether the bases pointed toward the helical axis or away, and ultimately what were the explicit angles and coordinates of all the bonds and atoms. Such questions motivated the modeling efforts of Watson and Crick.

Complementary nucleotides

In their modeling, Watson and Crick restricted themselves to what they saw as chemically and biologically reasonable. Still, the breadth of possibilities was very wide. A breakthrough occurred in 1952, when Erwin Chargaff visited Cambridge and inspired Crick with a description of experiments Chargaff had published in 1947. Chargaff had observed that the proportions of the four nucleotides vary between one DNA sample and the next, but that for particular pairs of nucleotides—adenine and thymine, guanine and cytosine—the two nucleotides are always present in equal proportions.

Using X-ray diffraction, as well as other data from Rosalind Franklin and her information that the bases were paired, James Watson and Francis Crick arrived at the first accurate model of DNA's molecular structure in 1953, which was accepted through inspection by Rosalind Franklin. The discovery was announced on February 28, 1953; the first Watson/Crick paper appeared in Nature on April 25, 1953. Sir Lawrence Bragg, the director of the Cavendish Laboratory, where Watson and Crick worked, gave a talk at Guy's Hospital Medical School in London on Thursday, May 14, 1953, which resulted in an article by Ritchie Calder in the News Chronicle of London, on Friday, May 15, 1953, entitled "Why You Are You. Nearer Secret of Life." The news reached readers of The New York Times the next day; Victor K. McElheny, in researching his biography, "Watson and DNA: Making a Scientific Revolution", found a clipping of a six-paragraph New York Times article written from London and dated May 16, 1953, with the headline "Form of 'Life Unit' in Cell Is Scanned." The article ran in an early edition and was then pulled to make space for news deemed more important. (The New York Times subsequently ran a longer article on June 12, 1953). The Cambridge University undergraduate newspaper also ran its own short article on the discovery on Saturday, May 30, 1953. Bragg's original announcement at a Solvay Conference on proteins in Belgium on April 8, 1953, went unreported by the press. In 1962 Watson, Crick, and Maurice Wilkins jointly received the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for their determination of the structure of DNA.

"Central Dogma"

Watson and Crick's model attracted great interest immediately upon its presentation. Arriving at their conclusion on February 21, 1953, Watson and Crick made their first announcement on February 28. In an influential presentation in 1957, Crick laid out the "central dogma of molecular biology", which foretold the relationship between DNA, RNA, and proteins, and articulated the "sequence hypothesis." A critical confirmation of the replication mechanism that was implied by the double-helical structure followed in 1958 in the form of the Meselson–Stahl experiment. Messenger RNA (mRNA) was identified as an intermediate between DNA sequences and protein synthesis by Brenner, Meselson, and Jacob in 1961. Then, work by Crick and coworkers showed that the genetic code was based on non-overlapping triplets of bases, called codons, and Har Gobind Khorana and others deciphered the genetic code not long afterward (1966). These findings represent the birth of molecular biology.

History of RNA tertiary structure

Pre-history: the helical structure of RNA

The earliest work in RNA structural biology coincided, more or less, with the work being done on DNA in the early 1950s. In their seminal 1953 paper, Watson and Crick suggested that van der Waals crowding by the 2`OH group of ribose would preclude RNA from adopting a double helical structure identical to the model they proposed—what we now know as B-form DNA. This provoked questions about the three-dimensional structure of RNA: could this molecule form some type of helical structure, and if so, how? As with DNA, early structural work on RNA centered around isolation of native RNA polymers for fiber diffraction analysis. In part because of heterogeneity of the samples tested, early fiber diffraction patterns were usually ambiguous and not readily interpretable. In 1955, Marianne Grunberg-Manago and colleagues published a paper describing the enzyme polynucleotide phosphorylase, which cleaved a phosphate group from nucleotide diphosphates to catalyze their polymerization. This discovery allowed researchers to synthesize homogenous nucleotide polymers, which they then combined to produce double stranded molecules. These samples yielded the most readily interpretable fiber diffraction patterns yet obtained, suggesting an ordered, helical structure for cognate, double stranded RNA that differed from that observed in DNA. These results paved the way for a series of investigations into the various properties and propensities of RNA. Through the late 1950s and early 1960s, numerous papers were published on various topics in RNA structure, including RNA-DNA hybridization, triple stranded RNA, and even small-scale crystallography of RNA di-nucleotides—G-C, and A-U—in primitive helix-like arrangements. For a more in-depth review of the early work in RNA structural biology, see the article The Era of RNA Awakening: Structural biology of RNA in the early years by Alexander Rich.

The beginning: crystal structure of tRNAPHE

In the mid-1960s, the role of tRNA in protein synthesis was being intensively studied. At this point, ribosomes had been implicated in protein synthesis, and it had been shown that an mRNA strand was necessary for the formation of these structures. In a 1964 publication, Warner and Rich showed that ribosomes active in protein synthesis contained tRNA molecules bound at the A and P sites, and discussed the notion that these molecules aided in the peptidyl transferase reaction. However, despite considerable biochemical characterization, the structural basis of tRNA function remained a mystery. In 1965, Holley et al. purified and sequenced the first tRNA molecule, initially proposing that it adopted a cloverleaf structure, based largely on the ability of certain regions of the molecule to form stem loop structures. The isolation of tRNA proved to be the first major windfall in RNA structural biology. Following Robert W. Holley's publication, numerous investigators began work on isolation tRNA for crystallographic study, developing improved methods for isolating the molecule as they worked. By 1968 several groups had produced tRNA crystals, but these proved to be of limited quality and did not yield data at the resolutions necessary to determine structure. In 1971, Kim et al. achieved another breakthrough, producing crystals of yeast tRNAPHE that diffracted to 2–3 Ångström resolutions by using spermine, a naturally occurring polyamine, which bound to and stabilized the tRNA. Despite having suitable crystals, however, the structure of tRNAPHE was not immediately solved at high resolution; rather it took pioneering work in the use of heavy metal derivatives and a good deal more time to produce a high-quality density map of the entire molecule. In 1973, Kim et al. produced a 4 Ångström map of the tRNA molecule in which they could unambiguously trace the entire backbone. This solution would be followed by many more, as various investigators worked to refine the structure and thereby more thoroughly elucidate the details of base pairing and stacking interactions, and validate the published architecture of the molecule.

The tRNAPHE structure is notable in the field of nucleic acid structure in general, as it represented the first solution of a long-chain nucleic acid structure of any kind—RNA or DNA—preceding Richard E. Dickerson's solution of a B-form dodecamer by nearly a decade. Also, tRNAPHE demonstrated many of the tertiary interactions observed in RNA architecture which would not be categorized and more thoroughly understood for years to come, providing a foundation for all future RNA structural research.

The renaissance: the hammerhead ribozyme and the group I intron: P4-6

For a considerable time following the first tRNA structures, the field of RNA structure did not dramatically advance. The ability to study an RNA structure depended upon the potential to isolate the RNA target. This proved limiting to the field for many years, in part because other known targets—i.e., the ribosome—were significantly more difficult to isolate and crystallize. Further, because other interesting RNA targets had simply not been identified, or were not sufficiently understood to be deemed interesting, there was simply a lack of things to study structurally. As such, for some twenty years following the original publication of the tRNAPHE structure, the structures of only a handful of other RNA targets were solved, with almost all of these belonging to the transfer RNA family. This unfortunate lack of scope would eventually be overcome largely because of two major advancements in nucleic acid research: the identification of ribozymes, and the ability to produce them via in vitro transcription.

Subsequent to Tom Cech's publication implicating the Tetrahymena group I intron as an autocatalytic ribozyme, and Sidney Altman's report of catalysis by ribonuclease P RNA, several other catalytic RNAs were identified in the late 1980s, including the hammerhead ribozyme. In 1994, McKay et al. published the structure of a 'hammerhead RNA-DNA ribozyme-inhibitor complex' at 2.6 Ångström resolution, in which the autocatalytic activity of the ribozyme was disrupted via binding to a DNA substrate. The conformation of the ribozyme published in this paper was eventually shown to be one of several possible states, and although this particular sample was catalytically inactive, subsequent structures have revealed its active-state architecture. This structure was followed by Jennifer Doudna's publication of the structure of the P4-P6 domains of the Tetrahymena group I intron, a fragment of the ribozyme originally made famous by Cech. The second clause in the title of this publication—Principles of RNA Packing—concisely evinces the value of these two structures: for the first time, comparisons could be made between well described tRNA structures and those of globular RNAs outside the transfer family. This allowed the framework of categorization to be built for RNA tertiary structure. It was now possible to propose the conservation of motifs, folds, and various local stabilizing interactions. For an early review of these structures and their implications, see RNA FOLDS: Insights from recent crystal structures, by Doudna and Ferre-D'Amare.

In addition to the advances being made in global structure determination via crystallography, the early 1990s also saw the implementation of NMR as a powerful technique in RNA structural biology. Coincident with the large-scale ribozyme structures being solved crystallographically, a number of structures of small RNAs and RNAs complexed with drugs and peptides were solved using NMR. In addition, NMR was now being used to investigate and supplement crystal structures, as exemplified by the determination of an isolated tetraloop-receptor motif structure published in 1997. Investigations such as this enabled a more precise characterization of the base pairing and base stacking interactions which stabilized the global folds of large RNA molecules. The importance of understanding RNA tertiary structural motifs was prophetically well described by Michel and Costa in their publication identifying the tetraloop motif: "...it should not come as a surprise if self-folding RNA molecules were to make intensive use of only a relatively small set of tertiary motifs. Identifying these motifs would greatly aid modeling enterprises, which will remain essential as long as the crystallization of large RNAs remains a difficult task".

The modern era: the age of RNA structural biology

The resurgence of RNA structural biology in the mid-1990s has caused a veritable explosion in the field of nucleic acid structural research. Since the publication of the hammerhead and P4-6 structures, numerous major contributions to the field have been made. Some of the most noteworthy examples include the structures of the Group I and Group II introns, and the Ribosome solved by Nenad Ban and colleagues in the laboratory of Thomas Steitz. The first three structures were produced using in vitro transcription, and that NMR has played a role in investigating partial components of all four structures—testaments to the indispensability of both techniques for RNA research. Most recently, the 2009 Nobel Prize in Chemistry was awarded to Ada Yonath, Venkatraman Ramakrishnan and Thomas Steitz for their structural work on the ribosome, demonstrating the prominent role RNA structural biology has taken in modern molecular biology.

History of protein biochemistry

First isolation and classification

Proteins were recognized as a distinct class of biological molecules in the eighteenth century by Antoine Fourcroy and others. Members of this class (called the "albuminoids", Eiweisskörper, or matières albuminoides) were recognized by their ability to coagulate or flocculate under various treatments such as heat or acid; well-known examples at the start of the nineteenth century included albumen from egg whites, blood serum albumin, fibrin, and wheat gluten. The similarity between the cooking of egg whites and the curdling of milk was recognized even in ancient times; for example, the name albumen for the egg-white protein was coined by Pliny the Elder from the Latin albus ovi (egg white).

With the advice of Jöns Jakob Berzelius, the Dutch chemist Gerhardus Johannes Mulder carried out elemental analyses of common animal and plant proteins. To everyone's surprise, all proteins had nearly the same empirical formula, roughly C400H620N100O120 with individual sulfur and phosphorus atoms. Mulder published his findings in two papers (1837,1838) and hypothesized that there was one basic substance (Grundstoff) of proteins, and that it was synthesized by plants and absorbed from them by animals in digestion. Berzelius was an early proponent of this theory and proposed the name "protein" for this substance in a letter dated 10 July 1838

The name protein that he propose for the organic oxide of fibrin and albumin, I wanted to derive from [the Greek word] πρωτειος, because it appears to be the primitive or principal substance of animal nutrition.

Mulder went on to identify the products of protein degradation such as the amino acid, leucine, for which he found a (nearly correct) molecular weight of 131 Da.

Purifications and measurements of mass

The minimum molecular weight suggested by Mulder's analyses was roughly 9 kDa, hundreds of times larger than other molecules being studied. Hence, the chemical structure of proteins (their primary structure) was an active area of research until 1949, when Fred Sanger sequenced insulin. The (correct) theory that proteins were linear polymers of amino acids linked by peptide bonds was proposed independently and simultaneously by Franz Hofmeister and Emil Fischer at the same conference in 1902. However, some scientists were sceptical that such long macromolecules could be stable in solution. Consequently, numerous alternative theories of the protein primary structure were proposed, e.g., the colloidal hypothesis that proteins were assemblies of small molecules, the cyclol hypothesis of Dorothy Wrinch, the diketopiperazine hypothesis of Emil Abderhalden and the pyrrol/piperidine hypothesis of Troensgard (1942). Most of these theories had difficulties in accounting for the fact that the digestion of proteins yielded peptides and amino acids. Proteins were finally shown to be macromolecules of well-defined composition (and not colloidal mixtures) by Theodor Svedberg using analytical ultracentrifugation. The possibility that some proteins are non-covalent associations of such macromolecules was shown by Gilbert Smithson Adair (by measuring the osmotic pressure of hemoglobin) and, later, by Frederic M. Richards in his studies of ribonuclease S. The mass spectrometry of proteins has long been a useful technique for identifying posttranslational modifications and, more recently, for probing protein structure.

Most proteins are difficult to purify in more than milligram quantities, even using the most modern methods. Hence, early studies focused on proteins that could be purified in large quantities, e.g., those of blood, egg white, various toxins, and digestive/metabolic enzymes obtained from slaughterhouses. Many techniques of protein purification were developed during World War II in a project led by Edwin Joseph Cohn to purify blood proteins to help keep soldiers alive. In the late 1950s, the Armour Hot Dog Co. purified 1 kg (= one million milligrams) of pure bovine pancreatic ribonuclease A and made it available at low cost to scientists around the world. This generous act made RNase A the main protein for basic research for the next few decades, resulting in several Nobel Prizes.

Protein folding and first structural models

The study of protein folding began in 1910 with a famous paper by Harriette Chick and C. J. Martin, in which they showed that the flocculation of a protein was composed of two distinct processes: the precipitation of a protein from solution was preceded by another process called denaturation, in which the protein became much less soluble, lost its enzymatic activity and became more chemically reactive. In the mid-1920s, Tim Anson and Alfred Mirsky proposed that denaturation was a reversible process, a correct hypothesis that was initially lampooned by some scientists as "unboiling the egg". Anson also suggested that denaturation was a two-state ("all-or-none") process, in which one fundamental molecular transition resulted in the drastic changes in solubility, enzymatic activity and chemical reactivity; he further noted that the free energy changes upon denaturation were much smaller than those typically involved in chemical reactions. In 1929, Hsien Wu hypothesized that denaturation was protein unfolding, a purely conformational change that resulted in the exposure of amino acid side chains to the solvent. According to this (correct) hypothesis, exposure of aliphatic and reactive side chains to solvent rendered the protein less soluble and more reactive, whereas the loss of a specific conformation caused the loss of enzymatic activity. Although considered plausible, Wu's hypothesis was not immediately accepted, since so little was known of protein structure and enzymology and other factors could account for the changes in solubility, enzymatic activity and chemical reactivity. In the early 1960s, Chris Anfinsen showed that the folding of ribonuclease A was fully reversible with no external cofactors needed, verifying the "thermodynamic hypothesis" of protein folding that the folded state represents the global minimum of free energy for the protein.

The hypothesis of protein folding was followed by research into the physical interactions that stabilize folded protein structures. The crucial role of hydrophobic interactions was hypothesized by Dorothy Wrinch and Irving Langmuir, as a mechanism that might stabilize her cyclol structures. Although supported by J. D. Bernal and others, this (correct) hypothesis was rejected along with the cyclol hypothesis, which was disproven in the 1930s by Linus Pauling (among others). Instead, Pauling championed the idea that protein structure was stabilized mainly by hydrogen bonds, an idea advanced initially by William Astbury (1933). Remarkably, Pauling's incorrect theory about H-bonds resulted in his correct models for the secondary structure elements of proteins, the alpha helix and the beta sheet. The hydrophobic interaction was restored to its correct prominence by a famous article in 1959 by Walter Kauzmann on denaturation, based partly on work by Kaj Linderstrøm-Lang. The ionic nature of proteins was demonstrated by Bjerrum, Weber and Arne Tiselius, but Linderstrom-Lang showed that the charges were generally accessible to solvent and not bound to each other (1949).

The secondary and low-resolution tertiary structure of globular proteins was investigated initially by hydrodynamic methods, such as analytical ultracentrifugation and flow birefringence. Spectroscopic methods to probe protein structure (such as circular dichroism, fluorescence, near-ultraviolet and infrared absorbance) were developed in the 1950s. The first atomic-resolution structures of proteins were solved by X-ray crystallography in the 1960s and by NMR in the 1980s. As of 2019, the Protein Data Bank has over 150,000 atomic-resolution structures of proteins. In more recent times, cryo-electron microscopy of large macromolecular assemblies has achieved atomic resolution, and computational protein structure prediction of small protein domains is approaching atomic resolution.