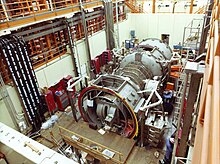

The Joint European Torus (JET) magnetic fusion experiment in 1991

Fusion power is a theoretical form of power generation in which energy will be generated by using nuclear fusion reactions to produce heat for electricity generation. In a fusion process, two lighter atomic nuclei combine to form a heavier nucleus, and at the same time, they release energy. This is the same process that powers stars like our Sun. Devices designed to harness this energy are known as fusion reactors.

Fusion processes require fuel and a highly confined environment with a high temperature and pressure, to create a plasma in which fusion can occur. In stars, the most common fuel is hydrogen, and gravity creates the high temperature and confinement needed for fusion. Fusion reactors generally use hydrogen isotopes such as deuterium and tritium, which react more easily, and create a confined plasma of millions of degrees using inertial methods (laser) or magnetic methods (tokamak

and similar), although many other concepts have been attempted. The

major challenges in realising fusion power are to engineer a system that

can confine the plasma long enough at high enough temperature and

density, for a long term reaction to occur, and for the most common

reactions, managing neutrons that are released during the reaction, which over time can degrade many common materials used within the reaction chamber.

As a source of power, nuclear fusion is expected to have several theoretical advantages over fission. These include reduced radioactivity in operation and little nuclear waste,

ample fuel supplies, and increased safety. However, controlled fusion

has proven to be extremely difficult to produce in a practical and

economical manner. Research into fusion reactors began in the 1940s, but

to date, no design has produced more fusion power output than the

electrical power input; therefore, all existing designs have had a

negative power balance.

Over the years, fusion researchers have investigated various

confinement concepts. The early emphasis was on three main systems: z-pinch, stellarator and magnetic mirror. The current leading designs are the tokamak and inertial confinement (ICF) by laser. Both designs are being built at very large scales, most notably the ITER tokamak in France, and the National Ignition Facility

laser in the United States. Researchers are also studying other designs

that may offer cheaper approaches. Among these alternatives there is

increasing interest in magnetized target fusion and inertial electrostatic confinement.

Background

The Sun, like other stars, is a natural fusion reactor, where stellar nucleosynthesis transforms lighter elements into heavier elements with the release of energy.

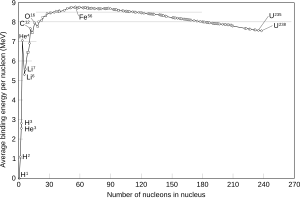

Binding energy for different atomic nuclei.

Iron-56 has the highest, making it the most stable. Nuclei to the left

are likely to fuse; those to the right are likely to split.

Mechanism

Fusion reactions occur when two or more atomic nuclei come close enough for long enough that the nuclear force pulling them together exceeds the electrostatic force pushing them apart, fusing them into heavier nuclei. For nuclei lighter than iron-56, the reaction is exothermic, releasing energy. For nuclei heavier than iron-56, the reaction is endothermic, requiring an external source of energy. Hence, nuclei smaller than iron-56 are more likely to fuse while those heavier than iron-56 are more likely to break apart.

The strong force acts only over short distances. The repulsive

electrostatic force acts over longer distances. In order to undergo

fusion, the fuel atoms need to be given enough energy to approach each

other close enough for the strong force to become active. The amount of kinetic energy needed to bring the fuel atoms close enough is known as the "Coulomb barrier". Ways of providing this energy include speeding up atoms in a particle accelerator, or heating them to high temperatures.

Once an atom is heated above its ionization energy, its electrons are stripped away (it is ionized), leaving just the bare nucleus (the ion). The result is a hot cloud of ions and the electrons formerly attached to them. This cloud is known as plasma.

Because the charges are separated, plasmas are electrically conductive

and magnetically controllable. Many fusion devices take advantage of

this to control the particles as they are heated.

Cross Section

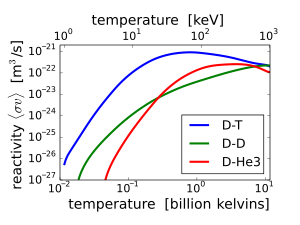

The

fusion reaction rate increases rapidly with temperature until it

maximizes and then gradually drops off. The deuterium-tritium fusion

rate peaks at a lower temperature (about 70 keV, or 800 million kelvin)

and at a higher value than other reactions commonly considered for

fusion energy.

A reaction's cross section,

denoted σ, is the measure of the probability that a fusion reaction

will happen. This depends on the relative velocity of the two nuclei.

Higher relative velocities generally increase the probability, but the

probability begins to decrease again at very high energies. Cross

sections for many fusion reactions were measured (mainly in the 1970s)

using particle beams.

In a plasma, particle velocity can be characterized using a

probability distribution. If the plasma is thermalized, the distribution

looks like a bell curve, or maxwellian distribution.

In this case, it is useful to use the average particle cross section

over the velocity distribution. This is entered into the volumetric

fusion rate:

where:

- is the energy made by fusion, per time and volume

- n is the number density of species A or B, of the particles in the volume

- is the cross section of that reaction, average over all the velocities of the two species v

- is the energy released by that fusion reaction.

Lawson Criterion

The

Lawson Criterion shows how energy output varies with temperature,

density, speed of collision, and fuel. This equation was central to John

Lawson's analysis of fusion working with a hot plasma. Lawson assumed

an energy balance, shown below.

- η, efficiency

- , conduction losses as energy laden mass leaves

- , radiation losses as energy leaves as light

- , net power from fusion

- , is rate of energy generated by the fusion reactions.

Plasma clouds lose energy through conduction and radiation. Conduction occurs when ions, electrons or neutrals

impact other substances, typically a surface of the device, and

transfer a portion of their kinetic energy to the other atoms. Radiation

is energy that leaves the cloud as light in the visible, UV, IR, or X-ray spectra. Radiation increases with temperature. Fusion power technologies must overcome these losses.

Triple product: density, temperature, time

The Lawson criterion argues that a machine holding a thermalized and quasi-neutral plasma has to meet basic criteria to overcome radiation losses, conduction losses and reach efficiency of 30 percent. This became known as the "triple product": the plasma density, temperature and confinement time.

Attempts to increase the triple product led to targeting larger plants.

Larger plants move structural materials further away from the centre of

the plasma, which reduces conduction and radiation losses since more of

the radiation is internally reflected. This emphasis on as a metric of success has impacted other considerations such as cost, size, complexity and efficiency. This has led to larger, more complicated and more expensive machines such as ITER and NIF.

Plasma behavior

Plasma is an ionized gas that conducts electricity. In bulk, it is modeled using magnetohydrodynamics, which is a combination of the Navier-Stokes equations governing fluids and Maxwell's equations governing how magnetic and electric fields behave. Fusion exploits several plasma properties, including:

- Self-organizing plasma conducts electric and magnetic fields. Its motions can generate fields that can in turn contain it.

- Diamagnetic plasma can generate its own internal magnetic field. This can reject an externally applied magnetic field, making it diamagnetic.

- Magnetic mirrors can reflect plasma when it moves from a low to high density field.

Energy capture

Multiple

approaches have been proposed for energy capture. The simplest is to

heat a fluid. Most designs concentrate on the D-T reaction, which

releases much of its energy in a neutron. Electrically neutral, the

neutron escapes the confinement. In most such designs, it is ultimately

captured in a thick "blanket" of lithium

surrounding the reactor core. When struck by a high-energy neutron, the

lithium can produce tritium, which is then fed back into the reactor.

The energy of this reaction also heats the blanket, which is then

actively cooled with a working fluid and then that fluid is used to

drive conventional turbomachinery.

It has also been proposed to use the neutrons to breed additional fission fuel in a blanket of nuclear waste, a concept known as a fission-fusion hybrid.

In these systems, the power output is enhanced by the fission events,

and power is extracted using systems like those in conventional fission

reactors.

Designs that use other fuels, notably the p-B reaction, release

much more of their energy in the form of charged particles. In these

cases, alternate power extraction systems based on the movement of these

charges are possible. Direct energy conversion was developed at LLNL

in the 1980s as a method to maintain a voltage using the fusion

reaction products. This has demonstrated energy capture efficiency of 48

percent.

Approaches

Magnetic confinement

- Tokamak: the most well-developed and well-funded approach to fusion energy. This method races hot plasma around in a magnetically confined, donut-shaped ring, with an internal current. When completed, ITER will be the world's largest tokamak. As of April 2012 an estimated 215 experimental tokamaks were either planned, decommissioned or currently operating (35) worldwide.

- Spherical tokamak: also known as spherical torus. A variation on the tokamak with a spherical shape.

- Stellarator: Twisted rings of hot plasma. The stellarator attempts to create a natural twisted plasma path, using external magnets, while tokamaks create those magnetic fields using an internal current. Stellarators were developed by Lyman Spitzer in 1950 and have four designs: Torsatron, Heliotron, Heliac and Helias. One example is Wendelstein 7-X, a German fusion device that produced its first plasma on December 10, 2015. It is the world's largest stellarator, designed to investigate the suitability of this type of device for a power station.

- Levitated Dipole Experiment (LDX): These use a solid superconducting torus. This is magnetically levitated inside the reactor chamber. The superconductor forms an axisymmetric magnetic field that contains the plasma. The LDX was developed by MIT and Columbia University after 2000 by Jay Kesner and Michael E. Mauel.

- Magnetic mirror: Developed by Richard F. Post and teams at LLNL in the 1960s. Magnetic mirrors reflected hot plasma back and forth in a line. Variations included the Tandem Mirror, magnetic bottle and the biconic cusp. A series of well-funded, large, mirror machines were built by the US government in the 1970s and 1980s, principally at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory.

- Bumpy torus: A number of magnetic mirrors are arranged end-to-end in a toroidal ring. Any fuel ions that leak out of one are confined in a neighboring mirror, permitting the plasma pressure to be raised arbitrarily high without loss. An experimental facility, the ELMO Bumpy Torus or EBT was built and tested at Oak Ridge National Laboratory in the 1970s.

- Field-reversed configuration: This device traps plasma in a self-organized quasi-stable structure; where the particle motion makes an internal magnetic field which then traps itself.

- Spheromak: Very similar to a field reversed configuration, a semi-stable plasma structure made by using the plasmas' own self-generated magnetic field. A spheromak has both a toroidal and poloidal fields, while a Field Reversed Configuration only has no toroidal field.

- Reversed field pinch: Here the plasma moves inside a ring. It has an internal magnetic field. Moving out from the center of this ring, the magnetic field reverses direction.

Inertial confinement

- Direct drive: In this technique, lasers directly blast a pellet of fuel. The goal is to ignite a fusion chain reaction. Ignition was first suggested by John Nuckolls, in 1972. Notable direct drive experiments have been conducted at the Laboratory for Laser Energetics, Laser Mégajoule and the GEKKO XII facilities. Good implosions require fuel pellets with close to a perfect shape in order to generate a symmetrical inward shock wave that produces the high-density plasma.

- Fast ignition: This method uses two laser blasts. The first blast compresses the fusion fuel, while the second high energy pulse ignites it. Experiments have been conducted at the Laboratory for Laser Energetics using the Omega and Omega EP systems and at the GEKKO XII laser at the Institute for Laser Engineering in Osaka Japan.

- Indirect drive: In this technique, lasers blasts a structure around the pellet of fuel. This structure is known as a Hohlraum. As it disintegrates the pellet is bathed in a more uniform x-ray light, creating better compression. The largest system using this method is the National Ignition Facility.

- Magneto-inertial fusion or Magnetized Liner Inertial Fusion: This combines a laser pulse with a magnetic pinch. The pinch community refers to it as magnetized liner Inertial fusion while the ICF community refers to it as magneto-inertial fusion.

- Heavy Ion Beams There are also proposals to do inertial confinement fusion with ion beams instead of laser beams. The main difference is the mass of the beam has momentum, whereas lasers do not.

Magnetic or electric pinches

- Z-Pinch: This method sends a strong current (in the z-direction) through the plasma. The current generates a magnetic field that squeezes the plasma to fusion conditions. Pinches were the first method for man-made controlled fusion. Some examples include the Dense plasma focus (DPF) and the Z machine at Sandia National Laboratories. In DPF the focus consists of two coaxial cylindrical electrodes made from copper or beryllium and housed in a vacuum chamber containing a low-pressure fusible gas. An electrical pulse is applied across the electrodes, heating the gas into a plasma. The current forms into a minuscule vortex along the axis of the machine, which then kinks into a cage of current with an associated magnetic field. The cage of current and magnetic-field-entrapped plasma is called a plasmoid. The acceleration of the electrons about the magnetic field lines heats the nuclei within the plasmoid to fusion temperatures.

- Theta-Pinch: This method sends a current inside a plasma, in the theta direction.

- Screw Pinch: This method combines a theta and z-pinch for improved stabilization.

Inertial electrostatic confinement

- Fusor: This method uses an electric field to heat ions to fusion conditions. The machine typically uses two spherical cages, a cathode inside the anode, inside a vacuum. These machines are not considered a viable approach to net power because of their high conduction and radiation losses. They are simple enough to build that amateurs have fused atoms using them.

- Polywell: This design attempts to combine magnetic confinement with electrostatic fields, to avoid the conduction losses generated by the cage.

Other

- Magnetized target fusion: This method confines hot plasma using a magnetic field and squeezes it using inertia. Examples include LANL FRX-L machine, General Fusion and the plasma liner experiment.

- Cluster Impact Fusion Microscopic droplets of heavy water are accelerated at great velocity into a target or into one another. Researchers at Brookhaven reported positive results which were later refuted by further experimentation. Fusion effects were actually produced because of contamination of the droplets.

- Uncontrolled: Fusion has been initiated by man, using uncontrolled fission explosions to ignite so-called Hydrogen Bombs. Early proposals for fusion power included using bombs to initiate reactions.

- Beam fusion: A beam of high energy particles can be fired at another beam or target and fusion will occur. This was used in the 1970s and 1980s to study the cross sections of high energy fusion reactions.

- Bubble fusion: This was a fusion reaction that was supposed to occur inside extraordinarily large collapsing gas bubbles, created during acoustic liquid cavitation. This approach was discredited.

- Cold fusion: This is a hypothetical type of nuclear reaction that would occur at, or near, room temperature. Cold fusion is discredited and gained a reputation as pathological science.

- Muon-catalyzed fusion: This approach replaces electrons in the plasma by muons - far more massive particles with the same electric charge. Their greater mass allows nuclei to get much closer and collide more easily, so it greatly reduces the kinetic energy (heat and pressure) required to initiate fusion. A problem is that muons require more energy to produce than can be obtained from muon-catalysed fusion, making this approach impractical for power generation.

- Space-Based Solar Power argues that a majority of available fusion fuels exists within the sphere of the Sun where it is gravitationally confined, and that a tractable way to accomplish large-scale fusion power is to build very large space-borne platforms that capture energy via photons rather than via a carnot cycle. The theoretical limit of producing power by such means is a type-2 civilization using a Dyson Sphere.

Common tools

Heating

Gas is heated to form a plasma hot enough to start fusion reactions. A number of heating schemes have been explored:

Radiofrequency Heating A radio wave is applied to the plasma, causing it to oscillate. This is basically the same concept as a microwave oven. This is also known as electron cyclotron resonance heating or Dielectric heating.

Electrostatic Heating An electric field can do work on charged ions or electrons, heating them.

Neutral Beam Injection

An external source of hydrogen is ionized and accelerated by an

electric field to form a charged beam which is shone through a source of

neutral hydrogen gas towards the plasma which itself is ionized and

contained in the reactor by a magnetic field. Some of the intermediate

hydrogen gas is accelerated towards the plasma by collisions with the

charged beam while remaining neutral: this neutral beam is thus

unaffected by the magnetic field and so shines through it into the

plasma. Once inside the plasma the neutral beam transmits energy to the

plasma by collisions as a result of which it becomes ionized and thus

contained by the magnetic field thereby both heating and refuelling the

reactor in one operation. The remainder of the charged beam is diverted

by magnetic fields onto cooled beam dumps.

Antiproton annihilation Theoretically a quantity of

antiprotons injected into a mass of fusion fuel can induce thermonuclear

reactions. This possibility as a method of spacecraft propulsion, known

as Antimatter-catalyzed nuclear pulse propulsion, was investigated at Pennsylvania State University in connection with the proposed AIMStar project.

Measurement

Thomson Scattering

Light scatters from plasma. This light can be detected and used to

reconstruct the plasmas' behavior. This technique can be used to find

its density and temperature. It is common in Inertial confinement fusion, Tokamaks and fusors.

In ICF systems, this can be done by firing a second beam into a gold

foil adjacent to the target. This makes x-rays that scatter or traverse

the plasma. In Tokamaks, this can be done using mirrors and detectors to

reflect light across a plane (two dimensions) or in a line (one

dimension).

Langmuir probe This is a metal object placed in a plasma. A potential is applied to it, giving it a positive or negative voltage

against the surrounding plasma. The metal collects charged particles,

drawing a current. As the voltage changes, the current changes. This

makes a IV Curve. The IV-curve can be used to determine the local plasma density, potential and temperature.

Neutron detectors Deuterium or tritium fusion produces neutrons. Neutrons interact with surrounding matter in ways that can be detected. Several types of neutron detectors exist

which can record the rate at which neutrons are produced during fusion

reactions. They are an essential tool for demonstrating success.

Flux loop

A loop of wire is inserted into the magnetic field. As the field passes

through the loop, a current is made. The current is measured and used

to find the total magnetic flux through that loop. This has been used on

the National Compact Stellarator Experiment, the polywell, and the LDX machines.

X-ray detector

All plasma loses energy by emitting light. This covers the whole

spectrum: visible, IR, UV, and X-rays. This occurs anytime a particle

changes speed, for any reason. If the reason is deflection by a magnetic field, the radiation is Cyclotron radiation at low speeds and Synchrotron radiation at high speeds. If the reason is deflection by another particle, plasma radiates X-rays, known as Bremsstrahlung radiation. X-rays are termed in both hard and soft, based on their energy.

Power production

It has been proposed that steam turbines be used to convert the heat from the fusion chamber into electricity. The heat is transferred into a working fluid that turns into steam, driving electric generators.

Neutron blankets Deuterium and tritium fusion generates neutrons. This varies by technique (NIF has a record of 3E14 neutrons per second while a typical fusor produces 1E5–1E9 neutrons per second). It has been proposed to use these neutrons as a way to regenerate spent fission fuel or as a way to breed tritium using a breeder blanket consisting of liquid lithium

or, as in more recent reactor designs, a helium cooled pebble bed

consisting of lithium bearing ceramic pebbles fabricated from materials

such as Lithium titanate, lithium orthosilicate or mixtures of these phases.

Direct conversion This is a method where the kinetic energy of a particle is converted into voltage. It was first suggested by Richard F. Post in conjunction with magnetic mirrors, in the late sixties. It has also been suggested for Field-Reversed Configurations.

The process takes the plasma, expands it, and converts a large fraction

of the random energy of the fusion products into directed motion. The

particles are then collected on electrodes at various large electrical

potentials. This method has demonstrated an experimental efficiency of

48 percent.

Records

Fusion records have been set by a number of devices. Here are some:

Q

The ratio of energy

extracted against the amount of energy supplied. This record is

considered to be set by the Joint European Torus (JET) in 1997 when the

device extracted 16 MW of power. However, this ratio can be seen three different ways.

- 0.69 is the actual point in time ratio between ”fusion power” and actual input power in the plasma (23 MW).

- 0.069 is the ratio between the “fusion” power and the power required to produce the 23MW input power (essentially it takes into account the efficiency of the NB system).

- 0.0069 is the ratio between the “fusion” power and the total peak power required for a JET pulse. This takes into account all the power from the grid plus the one from the two large JET flywheel generators.

Runtime

In

Field Reversed Configurations, the longest run time is 300 ms, set by

the Princeton Field Reversed Configuration in August 2016. However this involved no fusion.

Beta

The fusion power trends as the plasma confinement raised to the fourth power. Hence, getting a strong plasma trap is of real value to a fusion power plant. Plasma has a very good electrical conductivity. This opens the possibility of confining the plasma with magnetic field, generally known as magnetic confinement.

The field puts a magnetic pressure on the plasma, which holds it in. A

widely used measure of magnetic trapping in fusion is the beta ratio:

This is the ratio of the externally applied field to the internal

pressure of the plasma. A value of 1 is ideal trapping. Some examples

of beta values include:

- The START machine: 0.32

- The Levitated dipole experiment: 0.26

- Spheromaks: ≈ 0.1, Maximum 0.2 based on Mercier limit.

- The DIII-D machine: 0.126

- The Gas Dynamic Trap a magnetic mirror: 0.6 for 5E-3 seconds.

- The Sustained Spheromak Plasma Experiment at Los Alamos National labs < 0.05 for 4E-6 seconds.

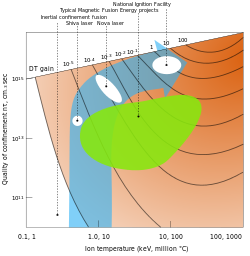

Confinement

Parameter space occupied by inertial fusion energy and magnetic fusion energy

devices as of the mid 1990s. The regime allowing thermonuclear ignition

with high gain lies near the upper right corner of the plot.

Confinement refers to all the conditions necessary to keep a plasma

dense and hot long enough to undergo fusion. Here are some general

principles.

- Equilibrium: The forces acting on the plasma must be balanced for containment. One exception is inertial confinement, where the relevant physics must occur faster than the disassembly time.

- Stability: The plasma must be so constructed so that disturbances will not lead to the plasma disassembling.

- Transport or conduction: The loss of material must be sufficiently slow. The plasma carries off energy with it, so rapid loss of material will disrupt any machines power balance. Material can be lost by transport into different regions or conduction through a solid or liquid.

To produce self-sustaining fusion, the energy released by the

reaction (or at least a fraction of it) must be used to heat new

reactant nuclei and keep them hot long enough that they also undergo

fusion reactions.

Unconfined

The first human-made, large-scale fusion reaction was the test of the hydrogen bomb, Ivy Mike, in 1952. As part of the PACER

project, it was once proposed to use hydrogen bombs as a source of

power by detonating them in underground caverns and then generating

electricity from the heat produced, but such a power station is unlikely

ever to be constructed.

Magnetic confinement

Magnetic Mirror One example of magnetic confinement is with the magnetic mirror

effect. If a particle follows the field line and enters a region of

higher field strength, the particles can be reflected. There are several

devices that try to use this effect. The most famous was the magnetic

mirror machines, which was a series of large, expensive devices built at

the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory from the 1960s to mid 1980s. Some other examples include the magnetic bottles and Biconic cusp.

Because the mirror machines were straight, they had some advantages

over a ring shape. First, mirrors were easier to construct and maintain

and second direct conversion energy capture, was easier to implement. As the confinement achieved in experiments was poor, this approach was abandoned.

Magnetic Loops Another example of magnetic confinement is

to bend the field lines back on themselves, either in circles or more

commonly in nested toroidal surfaces. The most highly developed system of this type is the tokamak, with the stellarator being next most advanced, followed by the Reversed field pinch. Compact toroids, especially the Field-Reversed Configuration and the spheromak, attempt to combine the advantages of toroidal magnetic surfaces with those of a simply connected (non-toroidal) machine, resulting in a mechanically simpler and smaller confinement area.

Inertial confinement

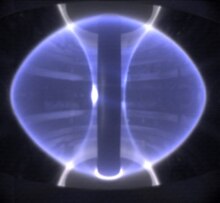

Inertial confinement

is the use of rapidly imploding shell to heat and confine plasma. The

shell is imploded using a direct laser blast (direct drive) or a

secondary x-ray blast (indirect drive) or heavy ion beams.

Theoretically, fusion using lasers would be done using tiny pellets of

fuel that explode several times a second. To induce the explosion, the

pellet must be compressed to about 30 times solid density with energetic

beams. If direct drive is used—the beams are focused directly on the

pellet—it can in principle be very efficient, but in practice is

difficult to obtain the needed uniformity. The alternative approach, indirect drive, uses beams to heat a shell, and then the shell radiates x-rays, which then implode the pellet. The beams are commonly laser beams, but heavy and light ion beams and electron beams have all been investigated.

Electrostatic confinement

There are also electrostatic confinement fusion devices. These devices confine ions using electrostatic fields. The best known is the Fusor.

This device has a cathode inside an anode wire cage. Positive ions fly

towards the negative inner cage, and are heated by the electric field in

the process. If they miss the inner cage they can collide and fuse.

Ions typically hit the cathode, however, creating prohibitory high conduction losses. Also, fusion rates in fusors are very low because of competing physical effects, such as energy loss in the form of light radiation.

Designs have been proposed to avoid the problems associated with the

cage, by generating the field using a non-neutral cloud. These include a

plasma oscillating device, a magnetically-shielded-grid, a penning trap, the polywell, and the F1 cathode driver concept. The technology is relatively immature, however, and many scientific and engineering questions remain.

History of research

1920s

Research into nuclear fusion started in the early part of the 20th century. In 1920 the British physicist Francis William Aston discovered that the total mass equivalent of four hydrogen atoms (two protons and two neutrons) are heavier than the total mass of one helium atom (He-4),

which implied that net energy can be released by combining hydrogen

atoms together to form helium, and provided the first hints of a

mechanism by which stars could produce energy in the quantities being

measured. Through the 1920s, Arthur Stanley Eddington became a major proponent of the proton–proton chain reaction (PP reaction) as the primary system running the Sun.

1930s

Neutrons from fusion was first detected by staff members of Ernest Rutherfords' at the University of Cambridge, in 1933. The experiment was developed by Mark Oliphant and involved the acceleration of protons towards a target at energies of up to 600,000 electron volts. In 1933, the Cavendish Laboratory received a gift from the American physical chemist Gilbert N. Lewis of a few drops of heavy water. The accelerator was used to fire heavy hydrogen nuclei deuterons at various targets. Working with Rutherford and others, Oliphant discovered the nuclei of Helium-3 (helions) and tritium (tritons).

A theory was verified by Hans Bethe in 1939 showing that beta decay and quantum tunneling in the Sun's core might convert one of the protons into a neutron and thereby producing deuterium

rather than a diproton. The deuterium would then fuse through other

reactions to further increase the energy output. For this work, Bethe

won the Nobel Prize in Physics.

1940s

The first patent related to a fusion reactor was registered in 1946 by the United Kingdom Atomic Energy Authority. The inventors were Sir George Paget Thomson and Moses Blackman. This was the first detailed examination of the Z-pinch

concept. Starting in 1947, two UK teams carried out small experiments

based on this concept and began building a series of ever-larger

experiments.

1950s

Early photo of plasma inside a pinch machine (imperial college 1950/1951)

The first successful man-made fusion device was the boosted fission weapon tested in 1951 in the Greenhouse Item test. This was followed by true fusion weapons in 1952's Ivy Mike, and the first practical examples in 1954's Castle Bravo.

This was uncontrolled fusion. In these devices, the energy released by

the fission explosion is used to compress and heat fusion fuel, starting

a fusion reaction. Fusion releases neutrons. These neutrons

hit the surrounding fission fuel, causing the atoms to split apart much

faster than normal fission processes—almost instantly by comparison.

This increases the effectiveness of bombs: normal fission weapons blow

themselves apart before all their fuel is used; fusion/fission weapons

do not have this practical upper limit.

In 1949 an expatriate German, Ronald Richter, proposed the Huemul Project

in Argentina, announcing positive results in 1951. These turned out to

be fake, but it prompted considerable interest in the concept as a

whole. In particular, it prompted Lyman Spitzer

to begin considering ways to solve some of the more obvious problems

involved in confining a hot plasma, and, unaware of the z-pinch efforts,

he developed a new solution to the problem known as the stellarator. Spitzer applied to the US Atomic Energy Commission for funding to build a test device. During this period, James L. Tuck who had worked with the UK teams on z-pinch had been introducing the concept to his new coworkers at the Los Alamos National Laboratory (LANL). When he heard of Spitzer's pitch for funding, he applied to build a machine of his own, the Perhapsatron.

Spitzer's idea won funding and he began work on the stellarator

under the code name Project Matterhorn. His work led to the creation of

the Princeton Plasma Physics Laboratory.

Tuck returned to LANL and arranged local funding to build his machine.

By this time, however, it was clear that all of the pinch machines were

suffering from the same issues involving instability, and progress

stalled. In 1953, Tuck and others suggested a number of solutions to the

stability problems. This led to the design of a second series of pinch

machines, led by the UK ZETA and Sceptre devices.

Spitzer had planned an aggressive development project of four

machines, A, B, C, and D. A and B were small research devices, C would

be the prototype of a power-producing machine, and D would be the

prototype of a commercial device. A worked without issue, but even by

the time B was being used it was clear the stellarator was also

suffering from instabilities and plasma leakage. Progress on C slowed as

attempts were made to correct for these problems.

By the mid-1950s it was clear that the simple theoretical tools

being used to calculate the performance of all fusion machines were

simply not predicting their actual behavior. Machines invariably leaked

their plasma from their confinement area at rates far higher than

predicted. In 1954, Edward Teller held a gathering of fusion researchers at the Princeton Gun Club, near the Project Matterhorn (now known as Project Sherwood)

grounds. Teller started by pointing out the problems that everyone was

having, and suggested that any system where the plasma was confined

within concave fields was doomed to fail. Attendees remember him saying

something to the effect that the fields were like rubber bands, and they

would attempt to snap back to a straight configuration whenever the

power was increased, ejecting the plasma. He went on to say that it

appeared the only way to confine the plasma in a stable configuration

would be to use convex fields, a "cusp" configuration.

When the meeting concluded, most of the researchers quickly

turned out papers saying why Teller's concerns did not apply to their

particular device. The pinch machines did not use magnetic fields in

this way at all, while the mirror and stellarator seemed to have various

ways out. This was soon followed by a paper by Martin David Kruskal and Martin Schwarzschild discussing pinch machines, however, which demonstrated instabilities in those devices were inherent to the design.

The largest "classic" pinch device was the ZETA, including all of these suggested upgrades, starting operations in the UK in 1957. In early 1958, John Cockcroft

announced that fusion had been achieved in the ZETA, an announcement

that made headlines around the world. When physicists in the US

expressed concerns about the claims they were initially dismissed. US

experiments soon demonstrated the same neutrons, although temperature

measurements suggested these could not be from fusion reactions. The

neutrons seen in the UK were later demonstrated to be from different

versions of the same instability processes that plagued earlier

machines. Cockcroft was forced to retract the fusion claims, and the

entire field was tainted for years. ZETA ended its experiments in 1968.

The first experiment to achieve controlled thermonuclear fusion was accomplished using Scylla I at the Los Alamos National Laboratory in 1958. Scylla I was a θ-pinch

machine, with a cylinder full of deuterium. Electric current shot down

the sides of the cylinder. The current made magnetic fields that pinched the plasma, raising temperatures to 15 million degrees Celsius, for long enough that atoms fused and produce neutrons.

The sherwood program sponsored a series of Scylla machines at Los

Alamos. The program began with 5 researchers and 100,000 in US funding

in January 1952. By 1965, a total of 21 million had been spent on the program and staffing never reached above 65.

In 1950–1951 I.E. Tamm and A.D. Sakharov in the Soviet Union, first discussed a tokamak-like approach. Experimental research on those designs began in 1956 at the Kurchatov Institute in Moscow by a group of Soviet scientists led by Lev Artsimovich.

The tokamak essentially combined a low-power pinch device with a

low-power simple stellarator. The key was to combine the fields in such a

way that the particles orbited within the reactor a particular number

of times, today known as the "safety factor".

The combination of these fields dramatically improved confinement times

and densities, resulting in huge improvements over existing devices.

1960s

A key plasma physics text was published by Lyman Spitzer at Princeton in 1963.

Spitzer took the ideal gas laws and adapted them to an ionized plasma,

developing many of the fundamental equations used to model a plasma.

Laser fusion was suggested in 1962 by scientists at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory,

shortly after the invention of the laser itself in 1960. At the time,

Lasers were low power machines, but low-level research began as early as

1965. Laser fusion, formally known as inertial confinement fusion, involves imploding a target by using laser

beams. There are two ways to do this: indirect drive and direct drive.

In direct drive, the laser blasts a pellet of fuel. In indirect drive,

the lasers blast a structure around the fuel. This makes x-rays that squeeze the fuel. Both methods compress the fuel so that fusion can take place.

At the 1964 World's Fair, the public was given its first demonstration of nuclear fusion. The device was a θ-pinch from General Electric. This was similar to the Scylla machine developed earlier at Los Alamos.

The magnetic mirror was first published in 1967 by Richard F. Post and many others at the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory.

The mirror consisted of two large magnets arranged so they had strong

fields within them, and a weaker, but connected, field between them.

Plasma introduced in the area between the two magnets would "bounce

back" from the stronger fields in the middle.

The A.D. Sakharov group constructed the first tokamaks, the most successful being the T-3 and its larger version T-4. T-4 was tested in 1968 in Novosibirsk, producing the world's first quasistationary fusion reaction.

When this were first announced, the international community was highly

skeptical. A British team was invited to see T-3, however, and after

measuring it in depth they released their results that confirmed the

Soviet claims. A burst of activity followed as many planned devices were

abandoned and new tokamaks were introduced in their place — the C model

stellarator, then under construction after many redesigns, was quickly

converted to the Symmetrical Tokamak.

In his work with vacuum tubes, Philo Farnsworth observed that electric charge would accumulate in regions of the tube. Today, this effect is known as the Multipactor effect.

Farnsworth reasoned that if ions were concentrated high enough they

could collide and fuse. In 1962, he filed a patent on a design using a

positive inner cage to concentrate plasma, in order to achieve nuclear

fusion. During this time, Robert L. Hirsch joined the Farnsworth Television labs and began work on what became the fusor. Hirsch patented the design in 1966 and published the design in 1967.

1970s

In 1972, John Nuckolls outlined the idea of ignition.

This is a fusion chain reaction. Hot helium made during fusion reheats

the fuel and starts more reactions. John argued that ignition would

require lasers of about 1 kJ. This turned out to be wrong. Nuckolls's

paper started a major development effort. Several laser systems were

built at LLNL. These included the argus, the Cyclops, the Janus, the long path, the Shiva laser and the Nova in 1984. This prompted the UK to build the Central Laser Facility in 1976.

During this time, great strides in understanding the tokamak

system were made. A number of improvements to the design are now part of

the "advanced tokamak" concept, which includes non-circular plasma,

internal diverters and limiters, often superconducting magnets, and

operate in the so-called "H-mode" island of increased stability. Two

other designs have also become fairly well studied; the compact tokamak

is wired with the magnets on the inside of the vacuum chamber, while the

spherical tokamak reduces its cross section as much as possible.

In 1974 a study of the ZETA results demonstrated an interesting

side-effect; after an experimental run ended, the plasma would enter a

short period of stability. This led to the reversed field pinch concept, which has seen some level of development since. On May 1, 1974, the KMS fusion company (founded by Kip Siegel) achieves the world's first laser induced fusion in a deuterium-tritium pellet.

In the mid-1970s, Project PACER,

carried out at Los Alamos National Laboratory (LANL) explored the

possibility of a fusion power system that would involve exploding small hydrogen bombs (fusion bombs) inside an underground cavity.

As an energy source, the system is the only fusion power system that

could be demonstrated to work using existing technology. It would also

require a large, continuous supply of nuclear bombs, however, making the

economics of such a system rather questionable.

In 1976, the two beam Argus laser becomes operational at livermore. In 1977, The 20 beam Shiva laser

at Livermore is completed, capable of delivering 10.2 kilojoules of

infrared energy on target. At a price of $25 million and a size

approaching that of a football field, Shiva is the first of the

megalasers. That same year, the JET project is approved by the European Commission and a site is selected.

1980s

The Novette target chamber (metal sphere with diagnostic devices protruding radially), which was reused from the Shiva project and two newly built laser chains visible in background.

Inertial confinement fusion implosion on the Nova laser during the 1980s was a key driver of fusion development.

As a result of advocacy, the cold war, and the 1970s energy crisis a massive magnetic mirror

program was funded by the US federal government in the late 1970s and

early 1980s. This program resulted in a series of large magnetic mirror

devices including: 2X, Baseball I, Baseball II, the Tandem Mirror Experiment, the Tandem mirror experiment upgrade, the Mirror Fusion Test Facility and the MFTF-B. These machines were built and tested at Livermore from the late 1960s to the mid 1980s. A number of institutions collaborated on these machines, conducting experiments. These included the Institute for Advanced Study and the University of Wisconsin–Madison. The last machine, the Mirror Fusion Test Facility cost 372 million dollars and was, at that time, the most expensive project in Livermore history.

It opened on February 21, 1986 and was promptly shut down. The reason

given was to balance the United States federal budget. This program was

supported from within the Carter and early Reagan administrations by Edwin E. Kintner, a US Navy captain, under Alvin Trivelpiece.

In Laser fusion progressed: in 1983, the NOVETTE laser was completed. The following December 1984, the ten beam NOVA laser was finished. Five years later, NOVA would produce a maximum of 120 kilojoules of infrared light, during a nanosecond pulse.

Meanwhile, efforts focused on either fast delivery or beam smoothness.

Both tried to deliver the energy uniformly to implode the target. One

early problem was that the light in the infrared wavelength, lost lots of energy before hitting the fuel. Breakthroughs were made at the Laboratory for Laser Energetics at the University of Rochester. Rochester scientists used frequency-tripling crystals to transform the infrared laser beams into ultraviolet beams. In 1985, Donna Strickland and Gérard Mourou

invented a method to amplify lasers pulses by "chirping". This method

changes a single wavelength into a full spectrum. The system then

amplifies the laser at each wavelength and then reconstitutes the beam

into one color. Chirp pulsed amplification became instrumental in

building the National Ignition Facility and the Omega EP system. Most

research into ICF was towards weapons research, because the implosion is

relevant to nuclear weapons.

During this time Los Alamos National Laboratory constructed a series of laser facilities. This included Gemini (a two beam system), Helios (eight beams), Antares (24 beams) and Aurora (96 beams). The program ended in the early nineties with a cost on the order of one billion dollars.

In 1987, Akira Hasegawa

noticed that in a dipolar magnetic field, fluctuations tended to

compress the plasma without energy loss. This effect was noticed in data

taken by Voyager 2, when it encountered Uranus. This observation would become the basis for a fusion approach known as the Levitated dipole.

In Tokamaks, the Tore Supra was under construction over the middle of the eighties (1983 to 1988). This was a Tokamak built in Cadarache, France. In 1983, the JET was completed and first plasmas achieved. In 1985, the Japanese tokamak, JT-60 was completed. In 1988, the T-15 a Soviet tokamak was completed. It was the first industrial fusion reactor to use superconducting magnets to control the plasma. These were Helium cooled.

In 1989, Pons and Fleischmann submitted papers to the Journal of Electroanalytical Chemistry claiming that they had observed fusion in a room temperature device and disclosing their work in a press release. Some scientists reported excess heat, neutrons, tritium, helium and other nuclear effects in so-called cold fusion

systems, which for a time gained interest as showing promise. Hopes

fell when replication failures were weighed in view of several reasons

cold fusion is not likely to occur, the discovery of possible sources of

experimental error, and finally the discovery that Fleischmann and Pons

had not actually detected nuclear reaction byproducts. By late 1989, most scientists considered cold fusion claims dead, and cold fusion subsequently gained a reputation as pathological science. However, a small community of researchers continues to investigate cold fusion claiming to replicate Fleishmann and Pons' results including nuclear reaction byproducts. Claims related to cold fusion are largely disbelieved in the mainstream scientific community. In 1989, the majority of a review panel organized by the US Department of Energy

(DOE) found that the evidence for the discovery of a new nuclear

process was not persuasive. A second DOE review, convened in 2004 to

look at new research, reached conclusions similar to the first.

In 1984, Martin Peng of ORNL proposed

an alternate arrangement of the magnet coils that would greatly reduce

the aspect ratio while avoiding the erosion issues of the compact

tokamak: a Spherical tokamak.

Instead of wiring each magnet coil separately, he proposed using a

single large conductor in the center, and wiring the magnets as

half-rings off of this conductor. What was once a series of individual

rings passing through the hole in the center of the reactor was reduced

to a single post, allowing for aspect ratios as low as 1.2.

The ST concept appeared to represent an enormous advance in tokamak

design. However, it was being proposed during a period when US fusion

research budgets were being dramatically scaled back. ORNL was provided

with funds to develop a suitable central column built out of a

high-strength copper alloy called "Glidcop". However, they were unable

to secure funding to build a demonstration machine, "STX". Failing to

build an ST at ORNL, Peng began a worldwide effort to interest other

teams in the ST concept and get a test machine built. One way to do this

quickly would be to convert a spheromak machine to the Spherical tokamak layout. Peng's advocacy also caught the interest of Derek Robinson, of the United Kingdom Atomic Energy Authority fusion center at Culham.

Robinson was able to gather together a team and secure funding on the

order of 100,000 pounds to build an experimental machine, the Small Tight Aspect Ratio Tokamak,

or START. Several parts of the machine were recycled from earlier

projects, while others were loaned from other labs, including a 40 keV

neutral beam injector from ORNL. Construction of START began in 1990, it was assembled rapidly and started operation in January 1991.

1990s

Mockup of a gold-plated hohlraum designed for use in the National Ignition Facility

In 1991 the Preliminary Tritium Experiment at the Joint European Torus in England achieved the world's first controlled release of fusion power.

In 1992, a major article was published in Physics Today by Robert McCory at the Laboratory for laser energetics outlying the current state of ICF and advocating for a national ignition facility. This was followed up by a major review article, from John Lindl in 1995, advocating for NIF.

During this time a number of ICF subsystems were developing, including

target manufacturing, cryogenic handling systems, new laser designs

(notably the NIKE laser at NRL) and improved diagnostics like time of flight analyzers and Thomson scattering. This work was done at the NOVA laser system, General Atomics, Laser Mégajoule and the GEKKO XII

system in Japan. Through this work and lobbying by groups like the

fusion power associates and John Sethian at NRL, a vote was made in

congress, authorizing funding for the NIF project in the late nineties.

In the early nineties, theory and experimental work regarding fusors and polywells was published. In response, Todd Rider at MIT developed general models of these devices.

Rider argued that all plasma systems at thermodynamic equilibrium were

fundamentally limited. In 1995, William Nevins published a criticism arguing that the particles inside fusors and polywells would build up angular momentum, causing the dense core to degrade.

In 1995, the University of Wisconsin–Madison built a large fusor, known as HOMER, which is still in operation. Meanwhile, Dr George H. Miley at Illinois, built a small fusor that has produced neutrons using deuterium gas and discovered the "star mode" of fusor operation.

The following year, the first "US-Japan Workshop on IEC Fusion", was

conducted. At this time in Europe, an IEC device was developed as a

commercial neutron source by Daimler-Chrysler and NSD Fusion.

In 1996, the Z-machine was upgraded and opened to the public by the US Army in August 1998 in Scientific American. The key attributes of Sandia's Z machine are its 18 million amperes and a discharge time of less than 100 nanoseconds. This generates a magnetic pulse, inside a large oil tank, this strikes an array of tungsten wires called a liner. Firing the Z-machine has become a way to test very high energy, high temperature (2 billion degrees) conditions. In 1996, the Tore Supra creates a plasma for two minutes with a current of almost 1 million amperes driven non-inductively by 2.3 MW of lower hybrid frequency waves.

This is 280 MJ of injected and extracted energy. This result was

possible because of the actively cooled plasma-facing components.

In 1997, JET produced a peak of 16.1MW of fusion power (65% of heat to plasma),

with fusion power of over 10MW sustained for over 0.5 sec. Its

successor, the International Thermonuclear Experimental Reactor (ITER), was officially announced as part of a seven-party consortium (six countries and the EU). ITER is designed to produce ten times more fusion power than the power put into the plasma. ITER is currently under construction in Cadarache, France.

In the late nineties, a team at Columbia University and MIT developed the Levitated dipole

a fusion device which consisted of a superconducting electromagnet,

floating in a saucer shaped vacuum chamber. Plasma swirled around this

donut and fused along the center axis.

2000s

Starting in 1999, a growing number of amateurs have been able to fuse atoms using homemade fusors, shown here.

The Mega Ampere Spherical Tokamak became operational in the UK in 1999

In the March 8, 2002 issue of the peer-reviewed journal Science, Rusi P. Taleyarkhan and colleagues at the Oak Ridge National Laboratory (ORNL) reported that acoustic cavitation experiments conducted with deuterated acetone (C3D6O) showed measurements of tritium and neutron output consistent with the occurrence of fusion. Taleyarkhan was later found guilty of misconduct, the Office of Naval Research debarred him for 28 months from receiving Federal Funding, and his name was listed in the 'Excluded Parties List'.

"Fast ignition" was developed in the late nineties, and was part of a push by the Laboratory for Laser Energetics

for building the Omega EP system. This system was finished in 2008.

Fast ignition showed such dramatic power savings that ICF appears to be a

useful technique for energy production. There are even proposals to

build an experimental facility dedicated to the fast ignition approach,

known as HiPER.

In April 2005, a team from UCLA announced it had devised a way of producing fusion using a machine that "fits on a lab bench", using lithium tantalate to generate enough voltage to smash deuterium atoms together. The process, however, does not generate net power (see Pyroelectric fusion). Such a device would be useful in the same sort of roles as the fusor. In 2006, China's EAST

test reactor is completed. This was the first tokamak to use

superconducting magnets to generate both the toroidal and poloidal

fields.

In the early 2000s, Researchers at LANL reasoned that a plasma oscillating could be at local thermodynamic equilibrium. This prompted the POPS and Penning trap designs. At this time, researchers at MIT became interested in fusors for space propulsion and powering space vehicles. Specifically, researchers developed fusors with multiple inner cages. Greg Piefer graduated from Madison and founded Phoenix Nuclear Labs, a company that developed the fusor into a neutron source for the mass production of medical isotopes. Robert Bussard began speaking openly about the Polywell in 2006. He attempted to generate interest in the research, before his death. In 2008, Taylor Wilson achieved notoriety for achieving nuclear fusion at 14, with a homemade fusor.

In March 2009, a high-energy laser system, the National Ignition Facility (NIF), located at the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, became operational.

The early 2000s saw the founding of a number of privately backed

fusion companies pursuing innovative approaches with the stated goal of

developing commercially viable fusion power plants. Secretive startup Tri Alpha Energy, founded in 1998, began exploring a field-reversed configuration approach. In 2002, Canadian company General Fusion began proof-of-concept experiments based on a hybrid magneto-inertial approach called Magnetized Target Fusion. These companies are funded by private investors including Jeff Bezos (General Fusion) and Paul Allen (Tri Alpha Energy). Toward the end of the decade, UK-based fusion company Tokamak Energy started exploring spherical tokamak devices.

2010s

The preamplifiers of the National Ignition Facility. In 2012, the NIF achieved a 500-terawatt shot.

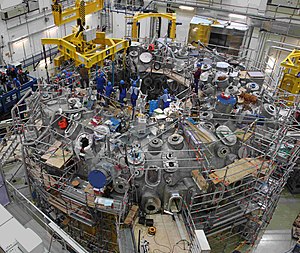

The Wendelstein7X under construction

Example

of a stellarator design: A coil system (blue) surrounds plasma

(yellow). A magnetic field line is highlighted in green on the yellow

plasma surface.

NIF, the French Laser Mégajoule and the planned European Union High Power laser Energy Research (HiPER) facility continued researching inertial (laser) confinement.

In 2010, NIF researchers conducted a series of "tuning" shots to

determine the optimal target design and laser parameters for high-energy

ignition experiments with fusion fuel.

Firing tests were performed on October 31, 2010 and November 2, 2010.

In early 2012, NIF director Mike Dunne expected the laser system to

generate fusion with net energy gain by the end of 2012.

However, that did not happen until August 2013. The facility reported

that their next step involved improving the system to prevent the

hohlraum from either breaking up asymmetrically or too soon.

A 2012 paper demonstrated that a dense plasma focus had achieved temperatures of 1.8 billion degrees Celsius, sufficient for boron fusion, and that fusion reactions were occurring primarily within the contained plasmoid, a necessary condition for net power.

In April 2014, Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory ended the Laser Inertial Fusion Energy (LIFE) program and redirected their efforts towards NIF. In August 2014, Phoenix Nuclear Labs announced the sale of a high-yield neutron generator that could sustain 5×1011 deuterium fusion reactions per second over a 24-hour period.

In October 2014, Lockheed Martin's Skunk Works announced the development of a high beta fusion reactor, the Compact Fusion Reactor, intending on making a 100-megawatt prototype by 2017 and beginning regular operation by 2022.

Although the original concept was to build a 20-ton, container-sized

unit, the team later conceded that the minimum scale would be 2,000

tons.

In January 2015, the polywell was presented at Microsoft Research.

In August, 2015, MIT announced a tokamak it named ARC fusion reactor using rare-earth barium-copper oxide

(REBCO) superconducting tapes to produce high-magnetic field coils that

it claimed produce comparable magnetic field strength in a smaller

configuration than other designs.

In October 2015, researchers at the Max Planck Institute of Plasma Physics completed building the largest stellarator to date, named Wendelstein 7-X.

On December 10, they successfully produced the first helium plasma, and

on February 3, 2016 produced the device's first hydrogen plasma.

With plasma discharges lasting up to 30 minutes, Wendelstein 7-X is

attempting to demonstrate the essential stellarator attribute:

continuous operation of a high-temperature hydrogen plasma.

General Fusion developed its plasma injector technology and Tri Alpha Energy constructed and operated its C-2U device.

In 2017 Helion Energy's fifth-generation plasma machine went into

operation, seeking to achieve plasma density of 20 Tesla and fusion

temperatures. In 2018 General Fusion was developing a 70% scale demo

system to be completed around 2023.

In 2018, energy corporation Eni announced a $50 million investment in the newly founded Commonwealth Fusion Systems, to attempt to commercialize ARC technology using a test reactor (SPARC) in collaboration with MIT.

Fuels

By firing

particle beams at targets, many fusion reactions have been tested, while

the fuels considered for power have all been light elements like the

isotopes of hydrogen—protium, deuterium, and tritium. The deuterium and helium-3

reaction requires helium-3, an isotope of helium so scarce on Earth

that it would have to be mined extraterrestrially or produced by other

nuclear reactions. Finally, researchers hope to perform the protium and

boron-11 reaction, because it does not directly produce neutrons, though

side reactions can.

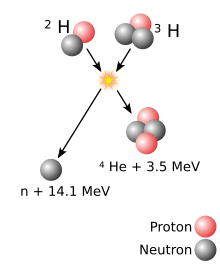

Deuterium, tritium

Diagram of the D-T reaction

The easiest nuclear reaction, at the lowest energy, is:

This reaction is common in research, industrial and military applications, usually as a convenient source of neutrons. Deuterium is a naturally occurring isotope

of hydrogen and is commonly available. The large mass ratio of the

hydrogen isotopes makes their separation easy compared to the difficult uranium enrichment process. Tritium is a natural isotope of hydrogen, but because it has a short half-life

of 12.32 years, it is hard to find, store, produce, and is expensive.

Consequently, the deuterium-tritium fuel cycle requires the breeding of tritium from lithium using one of the following reactions:

- 1

0n

+ 6

3Li

→ 3

1T

+ 4

2He - 1

0n

+ 7

3Li

→ 3

1T

+ 4

2He

+ 1

0n

The reactant neutron is supplied by the D-T fusion reaction shown

above, and the one that has the greatest yield of energy. The reaction

with 6Li is exothermic, providing a small energy gain for the reactor. The reaction with 7Li is endothermic

but does not consume the neutron. At least some neutron multiplication

reactions are required to replace the neutrons lost to absorption by

other elements. Leading candidate neutron multiplication materials are

beryllium and lead however the 7Li reaction above also helps to keep the neutron population high. Natural lithium is mainly 7Li however this has a low tritium production cross section compared to 6Li so most reactor designs use breeder blankets with enriched 6Li.

Several drawbacks are commonly attributed to D-T fusion power:

- It produces substantial amounts of neutrons that result in the neutron activation of the reactor materials.

- Only about 20% of the fusion energy yield appears in the form of charged particles with the remainder carried off by neutrons, which limits the extent to which direct energy conversion techniques might be applied.

- It requires the handling of the radioisotope tritium. Similar to hydrogen, tritium is difficult to contain and may leak from reactors in some quantity. Some estimates suggest that this would represent a fairly large environmental release of radioactivity.

The neutron flux expected in a commercial D-T fusion reactor is about 100 times that of current fission power reactors, posing problems for material design. After a series of D-T tests at JET, the vacuum vessel was sufficiently radioactive that remote handling was required for the year following the tests.

In a production setting, the neutrons would be used to react with lithium

in the context of a breeder blanket comprising lithium ceramic pebbles

or liquid lithium, in order to create more tritium. This also deposits

the energy of the neutrons in the lithium, which would then be

transferred to drive electrical production. The lithium neutron

absorption reaction protects the outer portions of the reactor from the

neutron flux. Newer designs, the advanced tokamak in particular, also

use lithium inside the reactor core as a key element of the design. The

plasma interacts directly with the lithium, preventing a problem known

as "recycling". The advantage of this design was demonstrated in the Lithium Tokamak Experiment.

Deuterium

Deuterium fusion cross section (in square meters) at different ion collision energies.

This is the second easiest fusion reaction, fusing two deuterium

nuclei. The reaction has two branches that occur with nearly equal

probability:

D + D → T + 1H D + D → 3He + n

This reaction is also common in research. The optimum energy to

initiate this reaction is 15 keV, only slightly higher than the optimum

for the D-T reaction. The first branch does not produce neutrons, but it

does produce tritium, so that a D-D reactor will not be completely

tritium-free, even though it does not require an input of tritium or

lithium. Unless the tritons can be quickly removed, most of the tritium

produced would be burned before leaving the reactor, which would reduce

the handling of tritium, but would produce more neutrons, some of which

are very energetic. The neutron from the second branch has an energy of

only 2.45 MeV (0.393 pJ), whereas the neutron from the D-T reaction has

an energy of 14.1 MeV (2.26 pJ), resulting in a wider range of isotope

production and material damage. When the tritons are removed quickly

while allowing the 3He to react, the fuel cycle is called "tritium suppressed fusion" The removed tritium decays to 3He with a 12.5 year half life. By recycling the 3He

produced from the decay of tritium back into the fusion reactor, the

fusion reactor does not require materials resistant to fast 14.1 MeV

(2.26 pJ) neutrons.

Assuming complete tritium burn-up, the reduction in the fraction

of fusion energy carried by neutrons would be only about 18%, so that

the primary advantage of the D-D fuel cycle is that tritium breeding

would not be required. Other advantages are independence from scarce

lithium resources and a somewhat softer neutron spectrum. The

disadvantage of D-D compared to D-T is that the energy confinement time

(at a given pressure) must be 30 times longer and the power produced (at

a given pressure and volume) would be 68 times less.

Assuming complete removal of tritium and recycling of 3He,

only 6% of the fusion energy is carried by neutrons. The

tritium-suppressed D-D fusion requires an energy confinement that is 10

times longer compared to D-T and a plasma temperature that is twice as

high.

Deuterium, helium-3

A second-generation approach to controlled fusion power involves combining helium-3 (3He) and deuterium (2H):

D + 3He → 4He + 1H

This reaction produces a helium-4 nucleus (4He) and a high-energy proton. As with the p-11B aneutronic fusion fuel cycle, most of the reaction energy is released as charged particles, reducing activation of the reactor housing and potentially allowing more efficient energy harvesting (via any of several speculative technologies). In practice, D-D side reactions produce a significant number of neutrons, resulting in p-11B being the preferred cycle for aneutronic fusion.

Protium, boron-11

If aneutronic fusion is the goal, then the most promising candidate may be the hydrogen-1 (protium) and boron reaction, which releases alpha (helium) particles, but does not rely on neutron scattering for energy transfer.

- 1H + 11B → 3 4He

Under reasonable assumptions, side reactions will result in about 0.1% of the fusion power being carried by neutrons.

At 123 keV, the optimum temperature for this reaction is nearly ten

times higher than that for the pure hydrogen reactions, the energy

confinement must be 500 times better than that required for the D-T

reaction, and the power density will be 2500 times lower than for D-T.

Because the confinement properties of conventional approaches to

fusion such as the tokamak and laser pellet fusion are marginal, most

proposals for aneutronic fusion are based on radically different

confinement concepts, such as the Polywell and the Dense Plasma Focus. Results have been extremely promising:

In the October 2013 edition of Nature Communications, a research team led by Christine Labaune at École Polytechnique in Palaiseau, France, reported a new record fusion rate: an estimated 80 million fusion reactions during the 1.5 nanoseconds that the laser fired, which is at least 100 times more than any previous proton-boron experiment.

Material selection

Considerations

Even

on smaller plasma production scales, the material of the containment

apparatus will be intensely blasted with matter and energy. Designs for

plasma containment must consider:

- A heating and cooling cycle, up to a 10 MW/m² thermal load.

- Neutron radiation, which over time leads to neutron activation and embrittlement.

- High energy ions leaving at tens to hundreds of electronvolts.

- Alpha particles leaving at millions of electronvolts.

- Electrons leaving at high energy.

- Light radiation (IR, visible, UV, X-ray).

Depending on the approach, these effects may be higher or lower than typical fission reactors like the pressurized water reactor (PWR). One estimate put the radiation at 100 times that of a typical PWR. Materials need to be selected or developed that can withstand these basic conditions. Depending on the approach, however, there may be other considerations such as electrical conductivity, magnetic permeability

and mechanical strength. There is also a need for materials whose

primary components and impurities do not result in long-lived

radioactive wastes.

Durability

For

long term use, each atom in the wall is expected to be hit by a neutron

and displaced about a hundred times before the material is replaced.

High-energy neutrons will produce hydrogen and helium by way of various

nuclear reactions that tends to form bubbles at grain boundaries and

result in swelling, blistering or embrittlement.

Selection

One can choose either a low-Z material, such as graphite or beryllium, or a high-Z material, usually tungsten with molybdenum

as a second choice. Use of liquid metals (lithium, gallium, tin) has

also been proposed, e.g., by injection of 1–5 mm thick streams flowing

at 10 m/s on solid substrates.

If graphite is used, the gross erosion rates due to physical and chemical sputtering

would be many meters per year, so one must rely on redeposition of the

sputtered material. The location of the redeposition will not exactly

coincide with the location of the sputtering, so one is still left with

erosion rates that may be prohibitive. An even larger problem is the

tritium co-deposited with the redeposited graphite. The tritium

inventory in graphite layers and dust in a reactor could quickly build

up to many kilograms, representing a waste of resources and a serious

radiological hazard in case of an accident. The consensus of the fusion

community seems to be that graphite, although a very attractive material

for fusion experiments, cannot be the primary plasma-facing material (PFM) in a commercial reactor.

The sputtering rate of tungsten by the plasma fuel ions is orders

of magnitude smaller than that of carbon, and tritium is much less

incorporated into redeposited tungsten, making this a more attractive

choice. On the other hand, tungsten impurities in a plasma are much more

damaging than carbon impurities, and self-sputtering of tungsten can be

high, so it will be necessary to ensure that the plasma in contact with

the tungsten is not too hot (a few tens of eV rather than hundreds of

eV). Tungsten also has disadvantages in terms of eddy currents and

melting in off-normal events, as well as some radiological issues.

Safety and the environment

Accident potential

Unlike nuclear fission,

fusion requires extremely precise and controlled temperature, pressure

and magnetic field parameters for any net energy to be produced. If a

reactor suffers damage or loses even a small degree of required control,

fusion reactions and heat generation would rapidly cease.

Additionally, fusion reactors contain only small amounts of fuel,

enough to "burn" for minutes, or in some cases, microseconds. Unless

they are actively refueled, the reactions will quickly end. Therefore,

fusion reactors are considered immune from catastrophic meltdown.

For similar reasons, runaway reactions cannot occur in a fusion reactor. The plasma

is burnt at optimal conditions, and any significant change will simply

quench the reactions. The reaction process is so delicate that this

level of safety is inherent. Although the plasma in a fusion power

station is expected to have a volume of 1,000 cubic metres

(35,000 cu ft) or more, the plasma density is low and typically contains

only a few grams of fuel in use.

If the fuel supply is closed, the reaction stops within seconds. In

comparison, a fission reactor is typically loaded with enough fuel for

several months or years, and no additional fuel is necessary to continue

the reaction. It is this large amount of fuel that gives rise to the

possibility of a meltdown; nothing like this exists in a fusion reactor.

In the magnetic approach, strong fields are developed in coils

that are held in place mechanically by the reactor structure. Failure of

this structure could release this tension and allow the magnet to

"explode" outward. The severity of this event would be similar to any

other industrial accident or an MRI machine quench/explosion, and could be effectively stopped with a containment building

similar to those used in existing (fission) nuclear generators. The

laser-driven inertial approach is generally lower-stress because of the

increased size of the reaction chamber. Although failure of the reaction

chamber is possible, simply stopping fuel delivery would prevent any

sort of catastrophic failure.

Most reactor designs rely on liquid hydrogen as both a coolant

and a method for converting stray neutrons from the reaction into tritium,

which is fed back into the reactor as fuel. Hydrogen is highly

flammable, and in the case of a fire it is possible that the hydrogen

stored on-site could be burned up and escape. In this case, the tritium

contents of the hydrogen would be released into the atmosphere, posing a

radiation risk. Calculations suggest that at about 1 kilogram (2.2 lb),

the total amount of tritium and other radioactive gases in a typical

power station would be so small that they would have diluted to legally

acceptable limits by the time they blew as far as the station's perimeter fence.

The likelihood of small industrial accidents, including the local

release of radioactivity and injury to staff, cannot be estimated yet.

These would include accidental releases of lithium or tritium or

mishandling of decommissioned radioactive components of the reactor

itself.

Magnet quench

A quench is an abnormal termination of magnet operation that occurs when part of the superconducting coil enters the normal (resistive) state. This can occur because the field inside the magnet is too large, the rate of change of field is too large (causing eddy currents and resultant heating in the copper support matrix), or a combination of the two.

More rarely a defect in the magnet can cause a quench. When this happens, that particular spot is subject to rapid Joule heating from the enormous current, which raises the temperature

of the surrounding regions. This pushes those regions into the normal

state as well, which leads to more heating in a chain reaction. The

entire magnet rapidly becomes normal (this can take several seconds,

depending on the size of the superconducting coil). This is accompanied

by a loud bang as the energy in the magnetic field is converted to heat,

and rapid boil-off of the cryogenic

fluid. The abrupt decrease of current can result in kilovolt inductive

voltage spikes and arcing. Permanent damage to the magnet is rare, but

components can be damaged by localized heating, high voltages, or large

mechanical forces.

In practice, magnets usually have safety devices to stop or limit

the current when the beginning of a quench is detected. If a large

magnet undergoes a quench, the inert vapor formed by the evaporating

cryogenic fluid can present a significant asphyxiation hazard to operators by displacing breathable air.