From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Variable speed of light (VSL) is a hypothesis that states that the speed of light, usually denoted by c, may be a function of space and time. Variable speed of light occurs in some situations of classical physics as equivalent formulations of accepted theories, but also in various alternative theories of gravitation and cosmology, many of them non-mainstream. In classical physics, the refractive index describes how light slows down when traveling through a medium. The speed of light in vacuum instead is considered a constant, and defined by the SI as 299792458 m/s. Alternative theories therefore usually modify the definitions of meter and seconds. VSL should not be confused with faster than light theories. Notable VSL attempts have been done by Einstein in 1911, by Robert Dicke in 1957, and by several researchers starting from the late 1980s. Since some of them contradict established concepts, VSL theories are a matter of debate.

, by means of

, by means of  , leads to a lower speed of light, Einstein assumed that clocks in a gravitational field run slower, whereby the corresponding frequencies

, leads to a lower speed of light, Einstein assumed that clocks in a gravitational field run slower, whereby the corresponding frequencies  are influenced by the gravitational potential (eq.2, p. 903):

are influenced by the gravitational potential (eq.2, p. 903):

, this resulted in a relative change of c twice as much as considered by Einstein. Dicke assumed a refractive index

, this resulted in a relative change of c twice as much as considered by Einstein. Dicke assumed a refractive index  (eqn.5) and proved it to be consistent with the observed value for light deflection. In a comment related to Mach's principle, Dicke suggested that, while the right part of the term in eq. 5 is small, the left part, 1, could have “its origin in the remainder of the matter in the universe”.

(eqn.5) and proved it to be consistent with the observed value for light deflection. In a comment related to Mach's principle, Dicke suggested that, while the right part of the term in eq. 5 is small, the left part, 1, could have “its origin in the remainder of the matter in the universe”.

Given that in a universe with an increasing horizon more and more masses contribute to the above refractive index, Dicke considered a cosmology where c decreased in time, providing an alternative explanation to the cosmological redshift [4] (p. 374). Dicke's theory does not contradict the SI definition of c= 299792458 m/s, since the time and length units second and meter can vary accordingly (p. 366).

denoting the gravitational potential −GM/r): "note that the photon speed is ...

denoting the gravitational potential −GM/r): "note that the photon speed is ...  ." Based on this, variable speed of light models have been developed which agree with all known tests of general relativity,[7] but some distinguish for higher-order tests.[8] Other models claim to shed light on the equivalence principle[9] or make a link to Dirac's Large Numbers Hypothesis.[10]

." Based on this, variable speed of light models have been developed which agree with all known tests of general relativity,[7] but some distinguish for higher-order tests.[8] Other models claim to shed light on the equivalence principle[9] or make a link to Dirac's Large Numbers Hypothesis.[10]

In Petit's VSL model, the variation of c accompanies the joint variations of all physical constants combined to space and time scale factors changes, so that all equations and measurements of these constants remain unchanged through the evolution of the universe. The Einstein field equations remain invariant through convenient joint variations of c and G in Einstein's constant. According to this model, the cosmological horizon grows like R, the space scale, which ensures the homogeneity of the primeval universe, which fits the observational data. Late-model restricts the variation of constants to the higher energy density of the early universe, at the very beginning of the radiation-dominated era where spacetime is identified to space-entropy with a metric conformally flat.[23][24]

The idea from Moffat and the team Albrecht–Magueijo is that light propagated as much as 60 orders of magnitude faster in the early universe, thus distant regions of the expanding universe have had time to interact at the beginning of the universe. There is no known way to solve the horizon problem with variation of the fine-structure constant, because its variation does not change the causal structure of spacetime. To do so would require modifying gravity by varying Newton's constant or redefining special relativity . Classically, varying speed of light cosmologies propose to circumvent this by varying the dimensionful quantity c by breaking the Lorentz invariance of Einstein's theories of general and special relativity in a particular way.[25][26] More modern formulations preserve local Lorentz invariance.[18]

Einstein's VSL attempt in 1911

While Einstein first mentioned a variable speed of light in 1907,[1] he reconsidered the idea more thoroughly in 1911.[2] In analogy to the situation in media, where a shorter wavelength , by means of

, by means of  , leads to a lower speed of light, Einstein assumed that clocks in a gravitational field run slower, whereby the corresponding frequencies

, leads to a lower speed of light, Einstein assumed that clocks in a gravitational field run slower, whereby the corresponding frequencies  are influenced by the gravitational potential (eq.2, p. 903):

are influenced by the gravitational potential (eq.2, p. 903):"Aus dem soeben bewiesenen Satze, daß die Lichtgeschwindigkeit im Schwerefelde eine Funktion des Ortes ist, läßt sich leicht mittels des Huygensschen Prinzipes schließen, daß quer zum Schwerefeld sich fortpflanzende Lichtstrahlen eine Krümmung erfahren müssen."In a subsequent paper in 1912 [3] he concluded that

("From the just proved assertion, that the speed of light in a gravity field is a function of position, it is easily deduced from Huygens's principle that light rays propagating at right angles to the gravity field must experience curvature.")

“Das Prinzip der Konstanz der Lichtgeschwindigkeit kann nur insofern aufrechterhalten werden, als man sich auf für Raum-Zeitliche-Gebiete mit konstantem Gravitationspotential beschränkt.“ (“The principle of the constancy of the speed of light can be kept only when one restricts oneself to space-time regions of constant gravitational potential.”)However, Einstein deduced a light deflection at the sun of “almost one arcsecond” which is just one-half of the correct value later derived by his theory of general relativity. While the correct value was later measured by Eddington in 1919, Einstein gave up his VSL theory for other reasons. Notably, in 1911 he had considered variable time only, while in general relativity, albeit in another theoretical context, both space and time measurements are influenced by nearby masses.

Dicke's 1957 attempt and Mach's principle

Robert Dicke, in 1957, developed a related VSL theory of gravity.[4] In contrast to Einstein, Dicke assumed not only the frequencies to vary, but also the wavelengths. Since , this resulted in a relative change of c twice as much as considered by Einstein. Dicke assumed a refractive index

, this resulted in a relative change of c twice as much as considered by Einstein. Dicke assumed a refractive index  (eqn.5) and proved it to be consistent with the observed value for light deflection. In a comment related to Mach's principle, Dicke suggested that, while the right part of the term in eq. 5 is small, the left part, 1, could have “its origin in the remainder of the matter in the universe”.

(eqn.5) and proved it to be consistent with the observed value for light deflection. In a comment related to Mach's principle, Dicke suggested that, while the right part of the term in eq. 5 is small, the left part, 1, could have “its origin in the remainder of the matter in the universe”.Given that in a universe with an increasing horizon more and more masses contribute to the above refractive index, Dicke considered a cosmology where c decreased in time, providing an alternative explanation to the cosmological redshift [4] (p. 374). Dicke's theory does not contradict the SI definition of c= 299792458 m/s, since the time and length units second and meter can vary accordingly (p. 366).

Though Dicke's attempt presented an alternative to general relativity, the notion of a spatial variation of the speed of light as such does not contradict general relativity. Rather it is implicitly present in general relativity, occurring in the coordinate space description, as it is mentioned in several textbooks, e.g. Will,[5] eqs. 6.14, 6.15, or Weinberg,[6] eq. 9.2.5 (

denoting the gravitational potential −GM/r): "note that the photon speed is ...

denoting the gravitational potential −GM/r): "note that the photon speed is ...  ." Based on this, variable speed of light models have been developed which agree with all known tests of general relativity,[7] but some distinguish for higher-order tests.[8] Other models claim to shed light on the equivalence principle[9] or make a link to Dirac's Large Numbers Hypothesis.[10]

." Based on this, variable speed of light models have been developed which agree with all known tests of general relativity,[7] but some distinguish for higher-order tests.[8] Other models claim to shed light on the equivalence principle[9] or make a link to Dirac's Large Numbers Hypothesis.[10]Modern VSL theories as an alternative to cosmic inflation

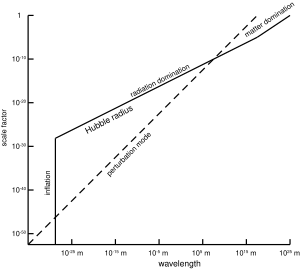

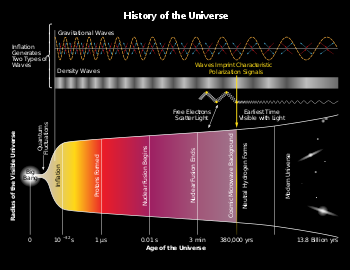

The varying speed of light cosmology has been proposed independently by Jean-Pierre Petit in 1988,[11][12][13][14] John Moffat in 1992,[15] and the two-man team of Andreas Albrecht and João Magueijo in 1998[16][17][18][19][20][21] to explain the horizon problem of cosmology and propose an alternative to cosmic inflation. An alternative VSL model has also been proposed.[22]In Petit's VSL model, the variation of c accompanies the joint variations of all physical constants combined to space and time scale factors changes, so that all equations and measurements of these constants remain unchanged through the evolution of the universe. The Einstein field equations remain invariant through convenient joint variations of c and G in Einstein's constant. According to this model, the cosmological horizon grows like R, the space scale, which ensures the homogeneity of the primeval universe, which fits the observational data. Late-model restricts the variation of constants to the higher energy density of the early universe, at the very beginning of the radiation-dominated era where spacetime is identified to space-entropy with a metric conformally flat.[23][24]

The idea from Moffat and the team Albrecht–Magueijo is that light propagated as much as 60 orders of magnitude faster in the early universe, thus distant regions of the expanding universe have had time to interact at the beginning of the universe. There is no known way to solve the horizon problem with variation of the fine-structure constant, because its variation does not change the causal structure of spacetime. To do so would require modifying gravity by varying Newton's constant or redefining special relativity . Classically, varying speed of light cosmologies propose to circumvent this by varying the dimensionful quantity c by breaking the Lorentz invariance of Einstein's theories of general and special relativity in a particular way.[25][26] More modern formulations preserve local Lorentz invariance.[18]

Various other VSL occurrences

Virtual photons

Virtual photons in some calculations in quantum field theory may also travel at a different speed for short distances; however, this doesn't imply that anything can travel faster than light. While it has been claimed (see VSL criticism below) that no meaning can be ascribed to a dimensional quantity such as the speed of light varying in time (as opposed to a dimensionless number such as the fine structure constant), in some controversial theories in cosmology, the speed of light also varies by changing the postulates of special relativity.[citation needed]Varying photon speed

The photon, the particle of light which mediates the electromagnetic force is believed to be massless. The so-called Proca action describes a theory of a massive photon.[27] Classically, it is possible to have a photon which is extremely light but nonetheless has a tiny mass, like the neutrino. These photons would propagate at less than the speed of light defined by special relativity and have three directions of polarization. However, in quantum field theory, the photon mass is not consistent with gauge invariance or renormalizability and so is usually ignored. However, a quantum theory of the massive photon can be considered in the Wilsonian effective field theory approach to quantum field theory, where, depending on whether the photon mass is generated by a Higgs mechanism or is inserted in an ad hoc way in the Proca Lagrangian, the limits implied by various observations/experiments may be different. So therefore, the speed of light is not constant.[28]Varying c in quantum theory

In quantum field theory the Heisenberg uncertainty relations indicate that photons can travel at any speed for short periods. In the Feynman diagram interpretation of the theory, these are known as "virtual photons", and are distinguished by propagating off the mass shell. These photons may have any velocity, including velocities greater than the speed of light. To quote Richard Feynman "...there is also an amplitude for light to go faster (or slower) than the conventional speed of light. You found out in the last lecture that light doesn't go only in straight lines; now, you find out that it doesn't go only at the speed of light! It may surprise you that there is an amplitude for a photon to go at speeds faster or slower than the conventional speed, c."[29] These virtual photons, however, do not violate causality or special relativity, as they are not directly observable and information cannot be transmitted acausally in the theory. Feynman diagrams and virtual photons are usually interpreted not as a physical picture of what is actually taking place, but rather as a convenient calculation tool (which, in some cases, happen to involve faster-than-light velocity vectors).Relation to other constants and their variation

Gravitational constant G

In 1937, Paul Dirac and others began investigating the consequences of natural constants changing with time.[30]

For example, Dirac proposed a change of only 5 parts in 1011 per year of Newton's constant G to explain the relative weakness of the gravitational force compared to other fundamental forces. This has become known as the Dirac large numbers hypothesis.

However, Richard Feynman showed in his famous lectures[31] that the gravitational constant most likely could not have changed this much in the past 4 billion years based on geological and solar system observations (although this may depend on assumptions about the constant not changing other constants). (See also strong equivalence principle.)

For over three decades since the discovery of the Oklo natural nuclear fission reactor in 1972, even more stringent constraints, placed by the study of certain isotopic abundances determined to be the products of a (estimated) 2 billion year-old fission reaction, seemed to indicate no variation was present.[36][37] However, Lamoreaux and Torgerson of the Los Alamos National Laboratory conducted a new analysis of the data from Oklo in 2004, and concluded that α has changed in the past 2 billion years by 4.5 parts in 108. They claimed that this finding was "probably accurate to within 20%." Accuracy is dependent on estimates of impurities and temperature in the natural reactor. These conclusions have yet to be verified by other researchers.[38][39][40]

Paul Davies and collaborators have suggested that it is in principle possible to disentangle which of the dimensionful constants (the elementary charge, Planck's constant, and the speed of light) of which the fine-structure constant is composed is responsible for the variation.[41] However, this has been disputed by others and is not generally accepted.[42][43]

For example, in the case of a hypothetically varying gravitational constant, G, the relevant dimensionless quantities that potentially vary ultimately become the ratios of the Planck mass to the masses of the fundamental particles. Some key dimensionless quantities (thought to be constant) that are related to the speed of light (among other dimensional quantities such as ħ, e, ε0), notably the fine-structure constant or the proton-to-electron mass ratio, does have meaningful variance and their possible variation continues to be studied.[46]

Specifically regarding VSL, if the SI meter definition was reverted to its pre-1960 definition as a length on a prototype bar (making it possible for the measure of c to change), then a conceivable change in c (the reciprocal of the amount of time taken for light to travel this prototype length) could be more fundamentally interpreted as a change in the dimensionless ratio of the meter prototype to the Planck length or as the dimensionless ratio of the SI second to the Planck time or a change in both. If the number of atoms making up the meter prototype remains unchanged (as it should for a stable prototype), then a perceived change in the value of c would be the consequence of the more fundamental change in the dimensionless ratio of the Planck length to the sizes of atoms or to the Bohr radius or, alternatively, as the dimensionless ratio of the Planck time to the period of a particular caesium-133 radiation or both.

However, Richard Feynman showed in his famous lectures[31] that the gravitational constant most likely could not have changed this much in the past 4 billion years based on geological and solar system observations (although this may depend on assumptions about the constant not changing other constants). (See also strong equivalence principle.)

Fine structure constant α

One group, studying distant quasars, has claimed to detect a variation of the fine structure constant [32] at the level in one part in 105. Other authors dispute these results. Other groups studying quasars claim no detectable variation at much higher sensitivities.[33][34][35]For over three decades since the discovery of the Oklo natural nuclear fission reactor in 1972, even more stringent constraints, placed by the study of certain isotopic abundances determined to be the products of a (estimated) 2 billion year-old fission reaction, seemed to indicate no variation was present.[36][37] However, Lamoreaux and Torgerson of the Los Alamos National Laboratory conducted a new analysis of the data from Oklo in 2004, and concluded that α has changed in the past 2 billion years by 4.5 parts in 108. They claimed that this finding was "probably accurate to within 20%." Accuracy is dependent on estimates of impurities and temperature in the natural reactor. These conclusions have yet to be verified by other researchers.[38][39][40]

Paul Davies and collaborators have suggested that it is in principle possible to disentangle which of the dimensionful constants (the elementary charge, Planck's constant, and the speed of light) of which the fine-structure constant is composed is responsible for the variation.[41] However, this has been disputed by others and is not generally accepted.[42][43]

Criticisms of the VSL concept

Dimensionless and dimensionful quantities

It has to be clarified what a variation in a dimensionful quantity actually means, since any such quantity can be changed merely by changing one's choice of units. John Barrow wrote:- "[An] important lesson we learn from the way that pure numbers like α define the world is what it really means for worlds to be different. The pure number we call the fine structure constant and denote by α is a combination of the electron charge, e, the speed of light, c, and Planck's constant, h. At first we might be tempted to think that a world in which the speed of light was slower would be a different world. But this would be a mistake. If c, h, and e were all changed so that the values they have in metric (or any other) units were different when we looked them up in our tables of physical constants, but the value of α remained the same, this new world would be observationally indistinguishable from our world. The only thing that counts in the definition of worlds are the values of the dimensionless constants of Nature. If all masses were doubled in value [including the Planck mass mP] you cannot tell because all the pure numbers defined by the ratios of any pair of masses are unchanged."[44]

For example, in the case of a hypothetically varying gravitational constant, G, the relevant dimensionless quantities that potentially vary ultimately become the ratios of the Planck mass to the masses of the fundamental particles. Some key dimensionless quantities (thought to be constant) that are related to the speed of light (among other dimensional quantities such as ħ, e, ε0), notably the fine-structure constant or the proton-to-electron mass ratio, does have meaningful variance and their possible variation continues to be studied.[46]

Relation to relativity and definition of c

In relativity, space-time is 4 dimensions of the same physical property of either space or time, depending on which perspective is chosen. The conversion factor of length=i*c*time is described in Appendix 2 of Einstein's Relativity. A changing c in relativity would mean the imaginary dimension of time is changing compared to the other three real-valued spacial dimensions of space-time.[citation needed]Specifically regarding VSL, if the SI meter definition was reverted to its pre-1960 definition as a length on a prototype bar (making it possible for the measure of c to change), then a conceivable change in c (the reciprocal of the amount of time taken for light to travel this prototype length) could be more fundamentally interpreted as a change in the dimensionless ratio of the meter prototype to the Planck length or as the dimensionless ratio of the SI second to the Planck time or a change in both. If the number of atoms making up the meter prototype remains unchanged (as it should for a stable prototype), then a perceived change in the value of c would be the consequence of the more fundamental change in the dimensionless ratio of the Planck length to the sizes of atoms or to the Bohr radius or, alternatively, as the dimensionless ratio of the Planck time to the period of a particular caesium-133 radiation or both.

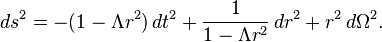

component on a fixed radius sphere called the

component on a fixed radius sphere called the  towards the cosmological horizon, which they cross in a finite proper time. This means that any inhomogeneities are smoothed out, just as any bumps or matter on the surface of a black hole horizon are swallowed and disappear.

towards the cosmological horizon, which they cross in a finite proper time. This means that any inhomogeneities are smoothed out, just as any bumps or matter on the surface of a black hole horizon are swallowed and disappear. everywhere. In this case, the

everywhere. In this case, the  . The physical conditions from one moment to the next are stable: the rate of expansion, called the

. The physical conditions from one moment to the next are stable: the rate of expansion, called the  . Inflation is often called a period of accelerated expansion because the distance between two fixed observers is increasing exponentially (i.e. at an accelerating rate as they move apart), while

. Inflation is often called a period of accelerated expansion because the distance between two fixed observers is increasing exponentially (i.e. at an accelerating rate as they move apart), while