From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

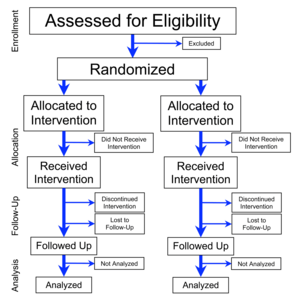

Flowchart of four phases (enrollment, intervention allocation,

follow-up, and data analysis) of a parallel randomized trial of two

groups, modified from the CONSORT (Consolidated Standards of Reporting

Trials) 2010 Statement

[1]

A

randomized controlled trial (or

randomized control trial;

[2] RCT)

is a type of scientific (often medical) experiment which aims to reduce

bias when testing a new treatment. The people participating in the

trial are randomly allocated to either the group receiving the treatment

under investigation or to a group receiving standard treatment (or

placebo treatment) as the control.

Randomization minimises

selection bias

and the different comparison groups allow the researchers to determine

any effects of the treatment when compared with the no treatment (

control) group, while other variables are kept constant. The RCT is often considered the

gold standard for a

clinical trial. RCTs are often used to test the

efficacy or

effectiveness of various types of medical

intervention and may provide information about adverse effects, such as

drug reactions.

Random assignment

of intervention is done after subjects have been assessed for

eligibility and recruited, but before the intervention to be studied

begins.

Random allocation in real trials is complex, but

conceptually the process is like

tossing a coin.

After randomization, the two (or more) groups of subjects are followed

in exactly the same way and the only differences between them is the

care they receive. For example, in terms of procedures, tests,

outpatient visits, and follow-up calls, should be those intrinsic to the

treatments being compared. The most important advantage of proper

randomization is that it minimizes allocation bias, balancing both known

and unknown prognostic factors, in the assignment of treatments.

[3]

The terms "RCT" and

randomized trial are sometimes used

synonymously, but the methodologically sound practice is to reserve the

"RCT" name only for trials that contain

control groups, in which groups receiving the experimental treatment are compared with control groups receiving no treatment (a

placebo-controlled study) or a previously tested treatment (a

positive-control study).

The term "randomized trials" omits mention of controls and can describe

studies that compare multiple treatment groups with each other (in the

absence of a control group).

[4] Similarly, although the "RCT" name is sometimes expanded as "

randomized clinical trial" or "

randomized comparative trial", the methodologically sound practice, to avoid ambiguity in the

scientific literature,

is to retain "control" in the definition of "RCT" and thus reserve that

name only for trials that contain controls. Not all randomized

clinical trials are randomized

controlled trials (and some of them could never be, in cases where controls would be impractical or unethical to institute). The term

randomized controlled clinical trials is a methodologically sound alternate expansion for "RCT" in RCTs that concern

clinical research;

[5][6][7] however, RCTs are also employed in other research areas, including many of the

social sciences.

History

The first reported

clinical trial was conducted by

James Lind in 1747 to identify treatment for

scurvy.

[8] Randomized experiments appeared in

psychology, where they were introduced by

Charles Sanders Peirce,

[9] and in

education.

[10][11][12] Later, randomized experiments appeared in agriculture, due to

Jerzy Neyman[13] and

Ronald A. Fisher. Fisher's experimental research and his writings popularized randomized experiments.

[14]

The first published RCT in medicine appeared in the 1948 paper entitled "

Streptomycin treatment of pulmonary

tuberculosis", which described a

Medical Research Council investigation.

[15][16][17] One of the authors of that paper was

Austin Bradford Hill, who is credited as having conceived the modern RCT.

[18]

By the late 20th century, RCTs were recognized as the standard method for "rational therapeutics" in medicine.

[19] As of 2004, more than 150,000 RCTs were in the

Cochrane Library.

[18] To improve the reporting of RCTs in the medical literature, an international group of scientists and editors published

Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) Statements in 1996, 2001 and 2010, and these have become widely accepted.

[1][3]

Randomization is the process of assigning trial subjects to treatment

or control groups using an element of chance to determine the

assignments in order to reduce the bias.

Ethics

Although the principle of

clinical equipoise ("genuine uncertainty within the expert medical community... about the preferred treatment") common to clinical trials

[20] has been applied to RCTs, the

ethics of RCTs have special considerations. For one, it has been argued that equipoise itself is insufficient to justify RCTs.

[21]

For another, "collective equipoise" can conflict with a lack of

personal equipoise (e.g., a personal belief that an intervention is

effective).

[22] Finally,

Zelen's design, which has been used for some RCTs, randomizes subjects

before they provide informed consent, which may be ethical for RCTs of

screening and selected therapies, but is likely unethical "for most therapeutic trials."

[23][24]

Although subjects almost always provide

informed consent

for their participation in an RCT, studies since 1982 have documented

that RCT subjects may believe that they are certain to receive treatment

that is best for them personally; that is, they do not understand the

difference between research and treatment.

[25][26] Further research is necessary to determine the prevalence of and ways to address this "

therapeutic misconception".

[26]

The RCT method variations may also create cultural effects that have not been well understood.

[27]

For example, patients with terminal illness may join trials in the hope

of being cured, even when treatments are unlikely to be successful.

Trial registration

In 2004, the

International Committee of Medical Journal Editors

(ICMJE) announced that all trials starting enrolment after July 1, 2005

must be registered prior to consideration for publication in one of the

12 member journals of the committee.

[28] However, trial registration may still occur late or not at all.

[29][30]

Medical journals have been slow in adapting policies requiring

mandatory clinical trial registration as a prerequisite for publication.

[31]

Classifications

By study design

One way to classify RCTs is by

study design. From most to least common in the healthcare literature, the major categories of RCT study designs are:

[32]

- Parallel-group

– each participant is randomly assigned to a group, and all the

participants in the group receive (or do not receive) an intervention.

- Crossover – over time, each participant receives (or does not receive) an intervention in a random sequence.[33][34]

- Cluster

– pre-existing groups of participants (e.g., villages, schools) are

randomly selected to receive (or not receive) an intervention.

- Factorial

– each participant is randomly assigned to a group that receives a

particular combination of interventions or non-interventions (e.g.,

group 1 receives vitamin X and vitamin Y, group 2 receives vitamin X and

placebo Y, group 3 receives placebo X and vitamin Y, and group 4

receives placebo X and placebo Y).

An analysis of the 616 RCTs indexed in

PubMed

during December 2006 found that 78% were parallel-group trials, 16%

were crossover, 2% were split-body, 2% were cluster, and 2% were

factorial.

[32]

By outcome of interest (efficacy vs. effectiveness)

RCTs can be classified as "explanatory" or "pragmatic."

[35] Explanatory RCTs test

efficacy in a research setting with highly selected participants and under highly controlled conditions.

[35] In contrast, pragmatic RCTs (pRCTs) test

effectiveness

in everyday practice with relatively unselected participants and under

flexible conditions; in this way, pragmatic RCTs can "inform decisions

about practice."

[35]

By hypothesis (superiority vs. noninferiority vs. equivalence)

Another

classification of RCTs categorizes them as "superiority trials",

"noninferiority trials", and "equivalence trials", which differ in

methodology and reporting.

[36] Most RCTs are superiority trials, in which one intervention is hypothesized to be superior to another in a

statistically significant way.

[36] Some RCTs are noninferiority trials "to determine whether a new treatment is no worse than a reference treatment."

[36] Other RCTs are equivalence trials in which the hypothesis is that two interventions are indistinguishable from each other.

[36]

Randomization

The advantages of proper

randomization in RCTs include:

[37]

- "It eliminates bias in treatment assignment," specifically selection bias and confounding.

- "It facilitates blinding (masking) of the identity of treatments from investigators, participants, and assessors."

- "It permits the use of probability theory to express the likelihood

that any difference in outcome between treatment groups merely indicates

chance."

There are two processes involved in randomizing patients to different interventions. First is choosing a

randomization procedure

to generate an unpredictable sequence of allocations; this may be a

simple random assignment of patients to any of the groups at equal

probabilities, may be "restricted", or may be "adaptive." A second and

more practical issue is

allocation concealment, which refers to

the stringent precautions taken to ensure that the group assignment of

patients are not revealed prior to definitively allocating them to their

respective groups. Non-random "systematic" methods of group assignment,

such as alternating subjects between one group and the other, can cause

"limitless contamination possibilities" and can cause a breach of

allocation concealment.

[38]

However empirical evidence that adequate randomization changes

outcomes relative to inadequate randomization has been difficult to

detect.

[39]

Procedures

The treatment allocation is the desired proportion of patients in each treatment arm.

An ideal randomization procedure would achieve the following goals:

[40]

- Maximize statistical power, especially in subgroup analyses.

Generally, equal group sizes maximize statistical power, however,

unequal groups sizes maybe more powerful for some analyses (e.g.,

multiple comparisons of placebo versus several doses using Dunnett’s

procedure[41]

), and are sometimes desired for non-analytic reasons (e.g., patients

maybe more motivated to enroll if there is a higher chance of getting

the test treatment, or regulatory agencies may require a minimum number

of patients exposed to treatment).[42]

- Minimize selection bias. This may occur if investigators can

consciously or unconsciously preferentially enroll patients between

treatment arms. A good randomization procedure will be unpredictable so

that investigators cannot guess the next subject's group assignment

based on prior treatment assignments. The risk of selection bias is

highest when previous treatment assignments are known (as in unblinded

studies) or can be guessed (perhaps if a drug has distinctive side

effects).

- Minimize allocation bias (or confounding). This may occur when covariates

that affect the outcome are not equally distributed between treatment

groups, and the treatment effect is confounded with the effect of the

covariates (i.e., an "accidental bias"[37][43]).

If the randomization procedure causes an imbalance in covariates

related to the outcome across groups, estimates of effect may be biased if not adjusted for the covariates (which may be unmeasured and therefore impossible to adjust for).

However, no single randomization procedure meets those goals in every

circumstance, so researchers must select a procedure for a given study

based on its advantages and disadvantages.

Simple

This is a commonly used and intuitive procedure, similar to "repeated fair coin-tossing."

[37] Also known as "complete" or "unrestricted" randomization, it is

robust

against both selection and accidental biases. However, its main

drawback is the possibility of imbalanced group sizes in small RCTs. It

is therefore recommended only for RCTs with over 200 subjects.

[44]

Restricted

To balance group sizes in smaller RCTs, some form of

"restricted" randomization is recommended.

[44] The major types of restricted randomization used in RCTs are:

- Permuted-block randomization or blocked randomization:

a "block size" and "allocation ratio" (number of subjects in one group

versus the other group) are specified, and subjects are allocated

randomly within each block.[38]

For example, a block size of 6 and an allocation ratio of 2:1 would

lead to random assignment of 4 subjects to one group and 2 to the other.

This type of randomization can be combined with "stratified

randomization", for example by center in a multicenter trial, to "ensure good balance of participant characteristics in each group."[3] A special case of permuted-block randomization is random allocation, in which the entire sample is treated as one block.[38]

The major disadvantage of permuted-block randomization is that even if

the block sizes are large and randomly varied, the procedure can lead to

selection bias.[40] Another disadvantage is that "proper" analysis of data from permuted-block-randomized RCTs requires stratification by blocks.[44]

- Adaptive biased-coin randomization methods (of which urn randomization

is the most widely known type): In these relatively uncommon methods,

the probability of being assigned to a group decreases if the group is

overrepresented and increases if the group is underrepresented.[38] The methods are thought to be less affected by selection bias than permuted-block randomization.[44]

Adaptive

At

least two types of "adaptive" randomization procedures have been used in

RCTs, but much less frequently than simple or restricted randomization:

- Covariate-adaptive randomization, of which one type is minimization: The probability of being assigned to a group varies in order to minimize "covariate imbalance."[44] Minimization is reported to have "supporters and detractors"[38]

because only the first subject's group assignment is truly chosen at

random, the method does not necessarily eliminate bias on unknown

factors.[3]

- Response-adaptive randomization, also known as outcome-adaptive randomization: The probability of being assigned to a group increases if the responses of the prior patients in the group were favorable.[44]

Although arguments have been made that this approach is more ethical

than other types of randomization when the probability that a treatment

is effective or ineffective increases during the course of an RCT,

ethicists have not yet studied the approach in detail.[45]

Allocation concealment

"Allocation

concealment" (defined as "the procedure for protecting the

randomization process so that the treatment to be allocated is not known

before the patient is entered into the study") is important in RCTs.

[46]

In practice, clinical investigators in RCTs often find it difficult to

maintain impartiality. Stories abound of investigators holding up sealed

envelopes to lights or ransacking offices to determine group

assignments in order to dictate the assignment of their next patient.

[38] Such practices introduce selection bias and

confounders (both of which should be minimized by randomization), thereby possibly distorting the results of the study.

[38]

Adequate allocation concealment should defeat patients and

investigators from discovering treatment allocation once a study is

underway and after the study has concluded. Treatment related

side-effects or adverse events may be specific enough to reveal

allocation to investigators or patients thereby introducing bias or

influencing any subjective parameters collected by investigators or

requested from subjects.

Some standard methods of ensuring allocation concealment include

sequentially numbered, opaque, sealed envelopes (SNOSE); sequentially

numbered containers; pharmacy controlled randomization; and central

randomization.

[38] It is recommended that allocation concealment methods be included in an RCT's

protocol,

and that the allocation concealment methods should be reported in

detail in a publication of an RCT's results; however, a 2005 study

determined that most RCTs have unclear allocation concealment in their

protocols, in their publications, or both.

[47] On the other hand, a 2008 study of 146

meta-analyses

concluded that the results of RCTs with inadequate or unclear

allocation concealment tended to be biased toward beneficial effects

only if the RCTs' outcomes were

subjective as opposed to

objective.

[48]

Sample size

The number of treatment units (subjects or groups of subjects)

assigned to control and treatment groups, affects an RCT's reliability.

If the effect of the treatment is small, the number of treatment units

in either group may be insufficient for rejecting the null hypothesis in

the respective

statistical test. The failure to reject the

null hypothesis would imply that the treatment shows no statistically significant effect on the treated

in a given test.

But as the sample size increases, the same RCT may be able to

demonstrate a significant effect of the treatment, even if this effect

is small.

[49]

Blinding

An RCT may be

blinded,

(also called "masked") by "procedures that prevent study participants,

caregivers, or outcome assessors from knowing which intervention was

received."

[48]

Unlike allocation concealment, blinding is sometimes inappropriate or

impossible to perform in an RCT; for example, if an RCT involves a

treatment in which active participation of the patient is necessary

(e.g.,

physical therapy), participants cannot be blinded to the intervention.

Traditionally, blinded RCTs have been classified as "single-blind",

"double-blind", or "triple-blind"; however, in 2001 and 2006 two studies

showed that these terms have different meanings for different people.

[50][51] The 2010

CONSORT Statement

specifies that authors and editors should not use the terms

"single-blind", "double-blind", and "triple-blind"; instead, reports of

blinded RCT should discuss "If done, who was blinded after assignment to

interventions (for example, participants, care providers, those

assessing outcomes) and how."

[3]

RCTs without blinding are referred to as "unblinded",

[52] "open",

[53] or (if the intervention is a medication) "

open-label".

[54]

In 2008 a study concluded that the results of unblinded RCTs tended to

be biased toward beneficial effects only if the RCTs' outcomes were

subjective as opposed to objective;

[48] for example, in an RCT of treatments for

multiple sclerosis, unblinded neurologists (but not the blinded neurologists) felt that the treatments were beneficial.

[55]

In pragmatic RCTs, although the participants and providers are often

unblinded, it is "still desirable and often possible to blind the

assessor or obtain an objective source of data for evaluation of

outcomes."

[35]

Analysis of data

The types of statistical methods used in RCTs depend on the characteristics of the data and include:

Regardless of the statistical methods used, important considerations in the analysis of RCT data include:

- Whether an RCT should be stopped early due to interim results. For

example, RCTs may be stopped early if an intervention produces "larger

than expected benefit or harm", or if "investigators find evidence of no

important difference between experimental and control interventions."[3]

- The extent to which the groups can be analyzed exactly as they existed upon randomization (i.e., whether a so-called "intention-to-treat analysis"

is used). A "pure" intention-to-treat analysis is "possible only when

complete outcome data are available" for all randomized subjects;[59] when some outcome data are missing, options include analyzing only cases with known outcomes and using imputed data.[3]

Nevertheless, the more that analyses can include all participants in

the groups to which they were randomized, the less bias that an RCT will

be subject to.[3]

- Whether subgroup analysis should be performed. These are "often discouraged" because multiple comparisons may produce false positive findings that cannot be confirmed by other studies.[3]

Reporting of results

The

CONSORT 2010 Statement is "an evidence-based, minimum set of recommendations for reporting RCTs."

[60]

The CONSORT 2010 checklist contains 25 items (many with sub-items)

focusing on "individually randomised, two group, parallel trials" which

are the most common type of RCT.

[1]

For other RCT study designs, "

CONSORT extensions" have been published, some examples are:

- Consort 2010 Statement: Extension to Cluster Randomised Trials[61]

- Consort 2010 Statement: Non-Pharmacologic Treatment Interventions[62][63]

Relative importance and observational studies

Two studies published in

The New England Journal of Medicine in 2000 found that

observational studies and RCTs overall produced similar results.

[64][65]

The authors of the 2000 findings questioned the belief that

"observational studies should not be used for defining evidence-based

medical care" and that RCTs' results are "evidence of the highest

grade."

[64][65] However, a 2001 study published in

Journal of the American Medical Association

concluded that "discrepancies beyond chance do occur and differences in

estimated magnitude of treatment effect are very common" between

observational studies and RCTs.

[66]

Two other lines of reasoning question RCTs' contribution to scientific knowledge beyond other types of studies:

- If study designs are ranked by their potential for new discoveries, then anecdotal evidence would be at the top of the list, followed by observational studies, followed by RCTs.[67]

- RCTs may be unnecessary for treatments that have dramatic and rapid

effects relative to the expected stable or progressively worse natural

course of the condition treated.[68][69] One example is combination chemotherapy including cisplatin for metastatic testicular cancer, which increased the cure rate from 5% to 60% in a 1977 non-randomized study.[69][70]

Interpretation of statistical results

Like all statistical methods, RCTs are subject to both

type I ("false positive") and type II ("false negative") statistical errors.

Regarding Type I errors, a typical RCT will use 0.05 (i.e., 1 in 20) as

the probability that the RCT will falsely find two equally effective

treatments significantly different.

[71] Regarding Type II errors, despite the publication of a 1978 paper noting that the

sample sizes of many "negative" RCTs were too small to make definitive conclusions about the negative results,

[72] by 2005-2006 a sizeable proportion of RCTs still had inaccurate or incompletely reported sample size calculations.

[73]

Advantages

RCTs are considered to be the most reliable form of

scientific evidence in the

hierarchy of evidence

that influences healthcare policy and practice because RCTs reduce

spurious causality and bias. Results of RCTs may be combined in

systematic reviews which are increasingly being used in the conduct of

evidence-based practice.

Some examples of scientific organizations' considering RCTs or

systematic reviews of RCTs to be the highest-quality evidence available

are:

Notable RCTs with unexpected results that contributed to changes in clinical practice include:

- After Food and Drug Administration approval, the antiarrhythmic agents flecainide and encainide came to market in 1986 and 1987 respectively.[78] The non-randomized studies concerning the drugs were characterized as "glowing",[79] and their sales increased to a combined total of approximately 165,000 prescriptions per month in early 1989.[78] In that year, however, a preliminary report of an RCT concluded that the two drugs increased mortality.[80] Sales of the drugs then decreased.[78]

- Prior to 2002, based on observational studies, it was routine for

physicians to prescribe hormone replacement therapy for post-menopausal

women to prevent myocardial infarction.[79] In 2002 and 2004, however, published RCTs from the Women's Health Initiative

claimed that women taking hormone replacement therapy with estrogen

plus progestin had a higher rate of myocardial infarctions than women on

a placebo, and that estrogen-only hormone replacement therapy caused no

reduction in the incidence of coronary heart disease.[58][81]

Possible explanations for the discrepancy between the observational

studies and the RCTs involved differences in methodology, in the hormone

regimens used, and in the populations studied.[82][83] The use of hormone replacement therapy decreased after publication of the RCTs.[84]

Disadvantages

Many papers discuss the disadvantages of RCTs.

[68][85][86]

A study published in 2018, assessing the 10 most cited randomised

controlled trials worldwide (each with 6,000+ citations), argues that

any RCT faces a broad set of assumptions, biases and constraints –

ranging from trials only being feasible to study a small set of

questions amendable to randomisation and generally only being able to

assess the

average treatment effect of a sample, to limitations

in extrapolating results to another context, among many others outlined

in the study.

[87] Among the most frequently cited drawbacks are:

Time and costs

RCTs can be expensive;

[86] one study found 28

Phase III RCTs funded by the

National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke prior to 2000 with a total cost of US$335 million,

[88] for a

mean cost of US$12 million per RCT. Nevertheless, the

return on investment

of RCTs may be high, in that the same study projected that the 28 RCTs

produced a "net benefit to society at 10-years" of 46 times the cost of

the trials program, based on evaluating a

quality-adjusted life year as equal to the prevailing mean

per capita gross domestic product.

[88]

The conduct of an RCT takes several years until being published, thus

data is restricted from the medical community for long years and may be

of less relevance at time of publication.

[89]

It is costly to maintain RCTs for the years or decades that would be ideal for evaluating some interventions.

[68][86]

Interventions to prevent events that occur only infrequently (e.g.,

sudden infant death syndrome)

and uncommon adverse outcomes (e.g., a rare side effect of a drug)

would require RCTs with extremely large sample sizes and may therefore

best be assessed by observational studies.

[68]

Due to the costs of running RCTs, these usually only inspect one

variable or very few variables, rarely reflecting the full picture of a

complicated medical situation; whereas the

case report, for example, can detail many aspects of the patient's

medical situation (e.g.

patient history,

physical examination,

diagnosis,

psychosocial aspects, follow up).

[89]

Conflict of interest dangers

A

2011 study done to disclose possible conflicts of interests in

underlying research studies used for medical meta-analyses reviewed 29

meta-analyses and found that conflicts of interests in the studies

underlying the meta-analyses were rarely disclosed. The 29 meta-analyses

included 11 from general medicine journals; 15 from specialty medicine

journals, and 3 from the

Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. The 29 meta-analyses reviewed an aggregate of 509

randomized controlled trials

(RCTs). Of these, 318 RCTs reported funding sources with 219 (69%)

industry funded. 132 of the 509 RCTs reported author conflict of

interest disclosures, with 91 studies (69%) disclosing industry

financial ties with one or more authors. The information was, however,

seldom reflected in the meta-analyses. Only two (7%) reported RCT

funding sources and none reported RCT author-industry ties. The authors

concluded "without acknowledgment of COI due to industry funding or

author industry financial ties from RCTs included in meta-analyses,

readers' understanding and appraisal of the evidence from the

meta-analysis may be compromised."

[90]

Some RCTs are fully or partly funded by the health care industry (e.g., the

pharmaceutical industry)

as opposed to government, nonprofit, or other sources. A systematic

review published in 2003 found four 1986–2002 articles comparing

industry-sponsored and nonindustry-sponsored RCTs, and in all the

articles there was a correlation of industry sponsorship and positive

study outcome.

[91]

A 2004 study of 1999–2001 RCTs published in leading medical and

surgical journals determined that industry-funded RCTs "are more likely

to be associated with statistically significant pro-industry findings."

[92]

These results have been mirrored in trials in surgery, where although

industry funding did not affect the rate of trial discontinuation it was

however associated with a lower odds of publication for completed

trials.

[93] One possible reason for the pro-industry results in industry-funded published RCTs is

publication bias.

[92]

Other authors have cited the differing goals of academic and industry

sponsored research as contributing to the difference. Commercial

sponsors may be more focused on performing trials of drugs that have

already shown promise in early stage trials, and on replicating previous

positive results to fulfill regulatory requirements for drug approval.

[94]

Ethics

If a

'disruptive' innovation in medical (or other) technology is developed,

it may be difficult to test this ethically in an RCT if it becomes

'obvious' that the control subjects have poorer outcomes—either due to

other foregoing testing, or within the initial phase of the RCT itself.

Ethically it may be necessary to abort the RCT prematurely, and getting

ethics approval (and patient agreement) to withhold the innovation from

the control group in future RCT's may not be feasible.

Historical control trials (HCT) exploit the data of previous RCTs to

reduce the sample size; however, these approaches are controversial in

the scientific community and must be handled with care.

[95]

In social science

Due

to the recent emergence of RCTs in social science, the use of RCTs in

social sciences is a contested issue. Some writers from a medical or

health background have argued that existing research in a range of

social science disciplines lacks rigour, and should be improved by

greater use of randomized control trials.

Transport science

Researchers

in transport science argue that public spending on programmes such as

school travel plans could not be justified unless their efficacy is

demonstrated by randomized controlled trials.

[96] Graham-Rowe and colleagues

[97]

reviewed 77 evaluations of transport interventions found in the

literature, categorising them into 5 "quality levels". They concluded

that most of the studies were of low quality and advocated the use of

randomized controlled trials wherever possible in future transport

research.

Dr. Steve Melia

[98]

took issue with these conclusions, arguing that claims about the

advantages of RCTs, in establishing causality and avoiding bias, have

been exaggerated. He proposed the following

8 criteria for the use of RCTs in contexts where interventions must change human behaviour to be effective:

The intervention:

- Has not been applied to all members of a unique group of people

(e.g. the population of a whole country, all employees of a unique

organisation etc.)

- Is applied in a context or setting similar to that which applies to the control group

- Can be isolated from other activities – and the purpose of the study is to assess this isolated effect

- Has a short timescale between its implementation and maturity of its effects

And the causal mechanisms:

- Are either known to the researchers, or else all possible alternatives can be tested

- Do not involve significant feedback mechanisms between the intervention group and external environments

- Have a stable and predictable relationship to exogenous factors

- Would act in the same way if the control group and intervention group were reversed

International development

RCTs

are currently being used by a number of international development

experts to measure the impact of development interventions worldwide.

Development economists at research organizations including

Abdul Latif Jameel Poverty Action Lab (J-PAL)

[99][100][101] and

Innovations for Poverty Action[102]

have used RCTs to measure the effectiveness of poverty, health, and

education programs in the developing world. While RCTs can be useful in

policy evaluation, it is necessary to exercise care in interpreting the

results in social science settings. For example, interventions can

inadvertently induce socioeconomic and behavioral changes that can

confound the relationships (Bhargava, 2008).

For some development economists, the main benefit to using RCTs

compared to other research methods is that randomization guards against

selection bias, a problem present in many current studies of development

policy. In one notable example of a cluster RCT in the field of

development economics, Olken (2007) randomized 608 villages in Indonesia

in which roads were about to be built into six groups (no audit vs.

audit, and no invitations to accountability meetings vs. invitations to

accountability meetings vs. invitations to accountability meetings along

with anonymous comment forms).

[103] After estimating "missing expenditures" (a measure of

corruption),

Olken concluded that government audits were more effective than

"increasing grassroots participation in monitoring" in reducing

corruption.

[103]

Overall, it is important in social sciences to account for the intended

as well as the unintended consequences of interventions for policy

evaluations.

Criminology

A

2005 review found 83 randomized experiments in criminology published in

1982-2004, compared with only 35 published in 1957-1981.

[104]

The authors classified the studies they found into five categories:

"policing", "prevention", "corrections", "court", and "community".

[104]

Focusing only on offending behavior programs, Hollin (2008) argued that

RCTs may be difficult to implement (e.g., if an RCT required "passing

sentences that would randomly assign offenders to programmes") and

therefore that experiments with

quasi-experimental design are still necessary.

[105]

Education

RCTs

have been used in evaluating a number of educational interventions. For

example, a 2009 study randomized 260 elementary school teachers'

classrooms to receive or not receive a program of behavioral screening,

classroom intervention, and parent training, and then measured the

behavioral and academic performance of their students.

[106]

Another 2009 study randomized classrooms for 678 first-grade children

to receive a classroom-centered intervention, a parent-centered

intervention, or no intervention, and then followed their academic

outcomes through age 19.

[107]

Mock randomised controlled trials, or simulations using

confectionery, can conducted in the classroom to teach students and

health professionals the principles of RCT design and

critical appraisal.

[108]

![{\displaystyle {\begin{array}{lll}\Delta G_{\text{bind}}=-RT\ln K_{\text{d}}\\[1.3ex]K_{\text{d}}={\dfrac {[{\text{Ligand}}][{\text{Receptor}}]}{[{\text{Complex}}]}}\\[1.3ex]\Delta G_{\text{bind}}=\Delta G_{\text{desolvation}}+\Delta G_{\text{motion}}+\Delta G_{\text{configuration}}+\Delta G_{\text{interaction}}\end{array}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/ba49ddd9dec7415d129787213744ca1afcd2d021)