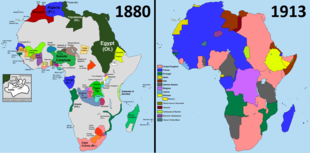

European powers during the period of New Imperialism, between 1881 and 1914. It is also called the Partition of Africa and by some the Conquest of Africa. In 1870, only 10 percent of Africa was under formal European control; by 1914 it had increased to almost 90 percent of the continent, with only Ethiopia (Abyssinia), the Dervish state (a portion of present-day Somalia) and Liberia still being independent. There were multiple motivations including the quest for national prestige, tensions between pairs of European powers, religious missionary zeal and internal African native politics.

The Berlin Conference of 1884, which regulated European colonisation and trade in Africa, is usually referred to as the ultimate point of the scramble for Africa.[2] Consequent to the political and economic rivalries among the European empires in the last quarter of the 19th century, the partitioning, or splitting up of Africa was how the Europeans avoided warring amongst themselves over Africa.[3] The later years of the 19th century saw the transition from "informal imperialism" (hegemony), by military influence and economic dominance, to direct rule, bringing about colonial imperialism.[4]

Background

David Livingstone, early explorer of the interior of Africa and fighter against the slave trade

By 1840 European powers had established small trading posts along the coast, but seldom moved inland.[5] In the middle decades of the 19th century, European explorers had mapped areas of East Africa and Central Africa.

Even as late as the 1870s, European states still controlled only ten percent of the African continent, with all their territories located near the coast. The most important holdings were Angola and Mozambique, held by Portugal; the Cape Colony, held by the United Kingdom; and Algeria, held by France. By 1914, only Ethiopia and Liberia remained independent of European control.[6]

Technological advances facilitated European expansion overseas. Industrialisation brought about rapid advancements in transportation and communication, especially in the forms of steamships, railways and telegraphs. Medical advances also played an important role, especially medicines for tropical diseases. The development of quinine, an effective treatment for malaria, made vast expanses of the tropics more accessible for Europeans.

Causes

Africa and global markets

Comparison of Africa in the years 1880 and 1913

Sub-Saharan Africa, one of the last regions of the world largely untouched by "informal imperialism", was also attractive to Europe's ruling elites for economic, political and social reasons. During a time when Britain's balance of trade showed a growing deficit, with shrinking and increasingly protectionist continental markets due to the Long Depression (1873–96), Africa offered Britain, Germany, France, and other countries an open market that would garner them a trade surplus: a market that bought more from the colonial power than it sold overall.[4][7]

Surplus capital was often more profitably invested overseas, where cheap materials, limited competition, and abundant raw materials made a greater premium possible. Another inducement for imperialism arose from the demand for raw materials, especially copper, cotton, rubber, palm oil, cocoa, diamonds, tea, and tin, to which European consumers had grown accustomed and upon which European industry had grown dependent. Additionally, Britain wanted the southern and eastern coasts of Africa for stopover ports on the route to Asia and its empire in India.[8] However, in Africa – excluding the area which became the Union of South Africa in 1910 – the amount of capital investment by Europeans was relatively small, compared to other continents. Consequently, the companies involved in tropical African commerce were relatively small, apart from Cecil Rhodes's De Beers Mining Company. Rhodes had carved out Rhodesia for himself; Léopold II of Belgium later, and with considerable brutality, exploited the Congo Free State.

These events might detract from the pro-imperialist arguments of colonial lobbyists such as the Alldeutscher Verband, Francesco Crispi and Jules Ferry, who argued that sheltered overseas markets in Africa would solve the problems of low prices and over-production caused by shrinking continental markets. John A. Hobson argued in Imperialism that this shrinking of continental markets was a key factor of the global "New Imperialism" period. William Easterly, however, disagrees with the link made between capitalism and imperialism, arguing that colonialism is used mostly to promote state-led development rather than "corporate" development. He has stated that "imperialism is not so clearly linked to capitalism and the free markets... historically there has been a closer link between colonialism/imperialism and state-led approaches to development."[9]

Strategic rivalry

Contemporary illustration of Major Marchand's trek across Africa in 1898

The rivalry between Britain, France, Germany, and the other European powers accounts for a large part of the colonization.

While tropical Africa was not a large zone of investment, other overseas regions were. The vast interior between Egypt and the gold and diamond-rich southern Africa had strategic value in securing the flow of overseas trade. Britain was under political pressure to secure lucrative markets against encroaching rivals in China and its eastern colonies, most notably India, Malaya, Australia and New Zealand. Thus, it was crucial to secure the key waterway between East and West—the Suez Canal. However, a theory that Britain sought to annex East Africa during the 1880 onwards, out of geostrategic concerns connected to Egypt (especially the Suez Canal),[10][11] has been challenged by historians such as John Darwin (1997) and Jonas F. Gjersø (2015).[12][13]

The scramble for African territory also reflected concern for the acquisition of military and naval bases, for strategic purposes and the exercise of power. The growing navies, and new ships driven by steam power, required coaling stations and ports for maintenance. Defense bases were also needed for the protection of sea routes and communication lines, particularly of expensive and vital international waterways such as the Suez Canal.[14]

Colonies were also seen as assets in "balance of power" negotiations, useful as items of exchange at times of international bargaining. Colonies with large native populations were also a source of military power; Britain and France used large numbers of British Indian and North African soldiers, respectively, in many of their colonial wars (and would do so again in the coming World Wars). In the age of nationalism there was pressure for a nation to acquire an empire as a status symbol; the idea of "greatness" became linked with the sense of duty underlying many nations' strategies.[14]

In the early 1880s, Pierre Savorgnan de Brazza was exploring the Kingdom of Kongo for France, at the same time Henry Morton Stanley explored it on behalf of Léopold II of Belgium, who would have it as his personal Congo Free State (see section below). France occupied Tunisia in May 1881, which may have convinced Italy to join the German-Austrian Dual Alliance in 1882, thus forming the Triple Alliance. The same year, Britain occupied Egypt (hitherto an autonomous state owing nominal fealty to the Ottoman Empire), which ruled over Sudan and parts of Chad, Eritrea, and Somalia. In 1884, Germany declared Togoland, the Cameroons and South West Africa to be under its protection; and France occupied Guinea. French West Africa (AOF) was founded in 1895, and French Equatorial Africa in 1910.[15][16]

Germany's Weltpolitik

The Askari colonial troops in German East Africa, circa 1906

Germany was hardly a colonial power before the New Imperialism period, but would eagerly participate in this race. Fragmented in various states, Germany was only unified under Prussia's rule after the 1866 Battle of Königgrätz and the 1870 Franco-Prussian War. A rising industrial power close on the heels of Britain, Germany began its world expansion in the 1880s. After isolating France by the Dual Alliance with Austria-Hungary and then the 1882 Triple Alliance with Italy, Chancellor Otto von Bismarck proposed the 1884–85 Berlin Conference, which set the rules of effective control of a foreign territory. Weltpolitik (world policy) was the foreign policy adopted by Kaiser Wilhelm II in 1890, with the aim of transforming Germany into a global power through aggressive diplomacy, the acquisition of overseas colonies, and the development of a large navy.

Some Germans, claiming themselves of Friedrich List's thought, advocated expansion in the Philippines and Timor; others proposed to set themselves up in Formosa (modern Taiwan), etc. At the end of the 1870s, these isolated voices began to be relayed by a real imperialist policy[citation needed], backed by mercantilist thesis. In 1881, Hübbe-Schleiden, a lawyer, published Deutsche Kolonisation, according to which the "development of national consciousness demanded an independent overseas policy".[17] Pan-Germanism was thus linked to the young nation's imperialist drives[citation needed]. In the beginning of the 1880s, the Deutscher Kolonialverein was created, and got its own magazine in 1884, the Kolonialzeitung. This colonial lobby was also relayed by the nationalist Alldeutscher Verband. Generally, Bismarck was opposed to widespread German colonialism,[18] but he had to resign at the insistence of the new German Emperor Wilhelm II on 18 March 1890. Wilhelm II instead adopted a very aggressive policy of colonisation and colonial expansion.

Germany's expansionism would lead to the Tirpitz Plan, implemented by Admiral von Tirpitz, who would also champion the various Fleet Acts starting in 1898, thus engaging in an arms race with Britain. By 1914, they had given Germany the second-largest naval force in the world (roughly three-fifths the size of the Royal Navy). According to von Tirpitz, this aggressive naval policy was supported by the National Liberal Party rather than by the conservatives, implying that imperialism was supported by the rising middle classes.[19]

Germany became the third-largest colonial power in Africa. Nearly all of its overall empire of 2.6 million square kilometres and 14 million colonial subjects in 1914 was found in its African possessions of Southwest Africa, Togoland, the Cameroons, and Tanganyika. Following the 1904 Entente cordiale between France and the British Empire, Germany tried to isolate France in 1905 with the First Moroccan Crisis. This led to the 1905 Algeciras Conference, in which France's influence on Morocco was compensated by the exchange of other territories, and then to the Agadir Crisis in 1911. Along with the 1898 Fashoda Incident between France and Britain, this succession of international crises reveals the bitterness of the struggle between the various imperialist nations, which ultimately led to World War I.

Italy's expansion

Tapestry depicting the Battle of Adwa between Ethiopian and Italian forces

Italy took possession of parts of Eritrea in 1870[20][21] and 1882. Following its defeat in the First Italo–Ethiopian War (1895–1896), it acquired Italian Somaliland in 1889–90 and the whole of Eritrea (1899). In 1911, it engaged in a war with the Ottoman Empire, in which it acquired Tripolitania and Cyrenaica (modern Libya). In 1919 Enrico Corradini—who fully supported the war, and later merged his group in the early fascist party (PNF)—developed the concept of Proletarian Nationalism, supposed to legitimise Italy's imperialism by a mixture of socialism with nationalism:

We must start by recognizing the fact that there are proletarian nations as well as proletarian classes; that is to say, there are nations whose living conditions are subject...to the way of life of other nations, just as classes are. Once this is realised, nationalism must insist firmly on this truth: Italy is, materially and morally, a proletarian nation.[22]The Second Italo-Abyssinian War (1935–36), ordered by the Fascist Benito Mussolini, would actually be one of the last colonial wars (that is, intended to colonise a foreign country, as opposed to wars of national liberation), occupying Ethiopia—which had remained the last independent African territory, apart from Liberia.

Crises prior to World War I

Colonisation of the Congo

David Livingstone's explorations, carried on by Henry Morton Stanley, excited imaginations with Stanley's grandiose ideas for colonisation; but these found little support owing to the problems and scale of action required, except from Léopold II of Belgium, who in 1876 had organised the International African Association (the Congo Society). From 1869 to 1874, Stanley was secretly sent by Léopold II to the Congo region, where he made treaties with several African chiefs along the Congo River and by 1882 had sufficient territory to form the basis of the Congo Free State. Léopold II personally owned the colony from 1885 and used it as a source of ivory and rubber.

Pierre Savorgnan de Brazza in his version of "native" dress, photographed by Félix Nadar

While Stanley was exploring Congo on behalf of Léopold II of Belgium, the Franco-Italian marine officer Pierre de Brazza travelled into the western Congo basin and raised the French flag over the newly founded Brazzaville in 1881, thus occupying today's Republic of the Congo. Portugal, which also claimed the area due to old treaties with the native Kongo Empire, made a treaty with Britain on 26 February 1884 to block off the Congo Society's access to the Atlantic.

By 1890 the Congo Free State had consolidated its control of its territory between Leopoldville and Stanleyville, and was looking to push south down the Lualaba River from Stanleyville. At the same time, the British South Africa Company of Cecil Rhodes was expanding north from the Limpopo River, sending the Pioneer Column (guided by Frederick Selous) through Matabeleland, and starting a colony in Mashonaland.

To the west, in the land where their expansions would meet, was Katanga, site of the Yeke Kingdom of Msiri. Msiri was the most militarily powerful ruler in the area, and traded large quantities of copper, ivory and slaves — and rumors of gold reached European ears. The scramble for Katanga was a prime example of the period. Rhodes and the BSAC sent two expeditions to Msiri in 1890 led by Alfred Sharpe, who was rebuffed, and Joseph Thomson, who failed to reach Katanga. Leopold sent four CFS expeditions. First, the Le Marinel Expedition could only extract a vaguely worded letter. The Delcommune Expedition was rebuffed. The well-armed Stairs Expedition was given orders to take Katanga with or without Msiri's consent. Msiri refused, was shot, and the expedition cut off his head and stuck it on a pole as a "barbaric lesson" to the people. The Bia Expedition finished the job of establishing an administration of sorts and a "police presence" in Katanga. Thus, the half million square kilometers of Katanga came into Leopold's possession and brought his African realm up to 2,300,000 square kilometres (890,000 sq mi), about 75 times larger than Belgium. The Congo Free State imposed such a terror regime on the colonised people, including mass killings and forced labour, that Belgium, under pressure from the Congo Reform Association, ended Leopold II's rule and annexed it in 1908 as a colony of Belgium, known as the Belgian Congo.

Native Congo Free State laborers who failed to meet rubber collection quotas were often punished by having their hands cut off.

The brutality of King Leopold II of Belgium in his former colony of the Congo Free State,[23][24] now the Democratic Republic of the Congo, was well documented; up to 8 million of the estimated 16 million native inhabitants died between 1885 and 1908.[25] According to the former British diplomat Roger Casement, this depopulation had four main causes: "indiscriminate war", starvation, reduction of births and diseases.[26] Sleeping sickness ravaged the country and must also be taken into account for the dramatic decrease in population; it has been estimated that sleeping sickness and smallpox killed nearly half the population in the areas surrounding the lower Congo River.[27]

Estimates of the total death toll vary considerably. As the first census did not take place until 1924, it is difficult to quantify the population loss of the period. Casement's report set it at three million.[28] William Rubinstein wrote: "More basically, it appears almost certain that the population figures given by Hochschild are inaccurate. There is, of course, no way of ascertaining the population of the Congo before the twentieth century, and estimates like 20 million are purely guesses. Most of the interior of the Congo was literally unexplored if not inaccessible."[29] See Congo Free State for further details including numbers of victims.

A similar situation occurred in the neighbouring French Congo. Most of the resource extraction was run by concession companies, whose brutal methods, along with the introduction of disease, resulted in the loss of up to 50 percent of the indigenous population.[30] The French government appointed a commission, headed by de Brazza, in 1905 to investigate the rumoured abuses in the colony. However, de Brazza died on the return trip, and his "searingly critical" report was neither acted upon nor released to the public.[31] In the 1920s, about 20,000 forced labourers died building a railroad through the French territory.[32]

Suez Canal

Port Said entrance to Suez Canal, showing De Lesseps' statue

French diplomat Ferdinand de Lesseps had obtained many concessions from Isma'il Pasha, the Khedive of Egypt and Sudan, in 1854–56, to build the Suez Canal. Some sources estimate the workforce at 30,000,[33] but others estimate that 120,000 workers died over the ten years of construction due to malnutrition, fatigue and disease, especially cholera.[34] Shortly before its completion in 1869, Khedive Isma'il borrowed enormous sums from British and French bankers at high rates of interest. By 1875, he was facing financial difficulties and was forced to sell his block of shares in the Suez Canal. The shares were snapped up by Britain, under its Prime Minister, Benjamin Disraeli, who sought to give his country practical control in the management of this strategic waterway. When Isma'il repudiated Egypt's foreign debt in 1879, Britain and France seized joint financial control over the country, forcing the Egyptian ruler to abdicate, and installing his eldest son Tewfik Pasha in his place. The Egyptian and Sudanese ruling classes did not relish foreign intervention.

During the 1870s, European initiatives against the slave trade caused an economic crisis in northern Sudan, precipitating the rise of Mahdist forces.[35] In 1881, the Mahdist revolt erupted in Sudan under Muhammad Ahmad, severing Tewfik's authority in Sudan. The same year, Tewfik suffered an even more perilous rebellion by his own Egyptian army in the form of the Urabi Revolt. In 1882, Tewfik appealed for direct British military assistance, commencing Britain's administration of Egypt. A joint British-Egyptian military force ultimately defeated the Mahdist forces in Sudan in 1898. Thereafter, Britain (rather than Egypt) seized effective control of Sudan.

Berlin Conference (1884–85)

Otto von Bismarck at the Berlin Conference, 1884

The occupation of Egypt, and the acquisition of the Congo were the first major moves in what came to be a precipitous scramble for African territory. In 1884, Otto von Bismarck convened the 1884–85 Berlin Conference to discuss the African problem. The diplomats put on a humanitarian façade by condemning the slave trade, prohibiting the sale of alcoholic beverages and firearms in certain regions, and by expressing concern for missionary activities. More importantly, the diplomats in Berlin laid down the rules of competition by which the great powers were to be guided in seeking colonies. They also agreed that the area along the Congo River was to be administered by Léopold II of Belgium as a neutral area, known as the Congo Free State, in which trade and navigation were to be free. No nation was to stake claims in Africa without notifying other powers of its intentions. No territory could be formally claimed prior to being effectively occupied. However, the competitors ignored the rules when convenient and on several occasions war was only narrowly avoided.[36]

Britain's administration of Egypt and South Africa

Britain's administration of Egypt and the Cape Colony contributed to a preoccupation over securing the source of the Nile River. Egypt was overrun by British forces in 1882 (although not formally declared a protectorate until 1914, and never an actual colony); Sudan, Nigeria, Kenya and Uganda were subjugated in the 1890s and early 20th century; and in the south, the Cape Colony (first acquired in 1795) provided a base for the subjugation of neighboring African states and the Dutch Afrikaner settlers who had left the Cape to avoid the British and then founded their own republics. Theophilus Shepstone annexed the South African Republic (or Transvaal) in 1877 for the British Empire, after it had been independent for twenty years. In 1879, after the Anglo-Zulu War, Britain consolidated its control of most of the territories of South Africa. The Boers protested, and in December 1880 they revolted, leading to the First Boer War (1880–81). British Prime Minister William Gladstone signed a peace treaty on 23 March 1881, giving self-government to the Boers in the Transvaal. The Jameson Raid of 1895 was a failed attempt by the British South Africa Company and the Johannesburg Reform Committee to overthrow the Boer government in the Transvaal. The Second Boer War, fought between 1899 and 1902, was about control of the gold and diamond industries; the independent Boer republics of the Orange Free State and the South African Republic (or Transvaal) were this time defeated and absorbed into the British Empire.

The French thrust into the African interior was mainly from the coasts of West Africa (modern day Senegal) eastward, through the Sahel along the southern border of the Sahara, a huge desert covering most of present-day Senegal, Mali, Niger, and Chad. Their ultimate aim was to have an uninterrupted colonial empire from the Niger River to the Nile, thus controlling all trade to and from the Sahel region, by virtue of their existing control over the Caravan routes through the Sahara. The British, on the other hand, wanted to link their possessions in Southern Africa (modern South Africa, Botswana, Zimbabwe, Lesotho, Swaziland, and Zambia), with their territories in East Africa (modern Kenya), and these two areas with the Nile basin.

Muhammad Ahmad, leader of the Mahdists. This fundamentalist group of Muslim dervishes over-ran much of Sudan and fought British forces.

The Sudan (which in those days included most of present-day Uganda) was the key to the fulfillment of these ambitions, especially since Egypt was already under British control. This "red line" through Africa is made most famous by Cecil Rhodes. Along with Lord Milner, the British colonial minister in South Africa, Rhodes advocated such a "Cape to Cairo" empire, linking the Suez Canal to the mineral-rich Southern part of the continent by rail. Though hampered by German occupation of Tanganyika until the end of World War I, Rhodes successfully lobbied on behalf of such a sprawling African empire.

If one draws a line from Cape Town to Cairo (Rhodes's dream), and one from Dakar to the Horn of Africa (now Ethiopia, Eritrea, Djibouti and Somalia), (the French ambition), these two lines intersect somewhere in eastern Sudan near Fashoda, explaining its strategic importance. In short, Britain had sought to extend its East African empire contiguously from Cairo to the Cape of Good Hope, while France had sought to extend its own holdings from Dakar to the Sudan, which would enable its empire to span the entire continent from the Atlantic Ocean to the Red Sea.

A French force under Jean-Baptiste Marchand arrived first at the strategically located fort at Fashoda, soon followed by a British force under Lord Kitchener, commander in chief of the British Army since 1892. The French withdrew after a standoff and continued to press claims to other posts in the region. In March 1899, the French and British agreed that the source of the Nile and Congo Rivers should mark the frontier between their spheres of influence.[citation needed]

Moroccan Crisis

Although the 1884–85 Berlin Conference had set the rules for the Scramble for Africa, it had not weakened the rival imperialists. The 1898 Fashoda Incident, which had seen France and the British Empire on the brink of war, ultimately led to the signature of the Entente Cordiale of 1904, which countered the influence of the European powers of the Triple Alliance. As a result, the new German Empire decided to test the solidity of such influence, using the contested territory of Morocco as a battlefield.Thus, Kaiser Wilhelm II visited Tangiers on 31 March 1905 and made a speech in favor of Moroccan independence, challenging French influence in Morocco. France's influence in Morocco had been reaffirmed by Britain and Spain in 1904. The Kaiser's speech bolstered French nationalism, and with British support the French foreign minister, Théophile Delcassé, took a defiant line. The crisis peaked in mid-June 1905, when Delcassé was forced out of the ministry by the more conciliation-minded premier Maurice Rouvier. But by July 1905 Germany was becoming isolated and the French agreed to a conference to solve the crisis. Both France and Germany continued to posture up until the conference, with Germany mobilizing reserve army units in late December and France actually moving troops to the border in January 1906.

The Moroccan Sultan Abdelhafid, who led the resistance to French expansionism during the Agadir Crisis

The 1906 Algeciras Conference was called to settle the dispute. Of the thirteen nations present, the German representatives found their only supporter was Austria-Hungary. France had firm support from Britain, the US, Russia, Italy and Spain. The Germans eventually accepted an agreement, signed on 31 May 1906, whereby France yielded certain domestic changes in Morocco but retained control of key areas.

However, five years later the Second Moroccan Crisis (or Agadir Crisis) was sparked by the deployment of the German gunboat Panther to the port of Agadir on 1 July 1911. Germany had started to attempt to surpass Britain's naval supremacy—the British navy had a policy of remaining larger than the next two naval fleets in the world combined. When the British heard of the Panther's arrival in Morocco, they wrongly believed that the Germans meant to turn Agadir into a naval base on the Atlantic.

The German move was aimed at reinforcing claims for compensation for acceptance of effective French control of the North African kingdom, where France's pre-eminence had been upheld by the 1906 Algeciras Conference. In November 1911 a convention was signed under which Germany accepted France's position in Morocco in return for territory in the French Equatorial African colony of Middle Congo (now the Republic of the Congo).

France and Spain subsequently established a full protectorate over Morocco (30 March 1912), ending what remained of the country's formal independence. Furthermore, British backing for France during the two Moroccan crises reinforced the Entente between the two countries and added to Anglo-German estrangement, deepening the divisions that would culminate in the First World War.

Dervish resistance

Statue of Sayyid Mohammed Abdullah Hassan (the "Mad Mullah"), leader of the Dervish State

Following the Berlin Conference at the end of the 19th century, the British, Italians, and Ethiopians sought to claim lands owned by the Somalis such as the Warsangali Sultanate, the Ajuran Sultanate and the Gobroon Dynasty.

The Dervish State was a state established by Mohammed Abdullah Hassan, a Somali religious leader who gathered Muslim soldiers from across the Horn of Africa and united them into a loyal army known as the Dervishes. This Dervish army enabled Hassan to carve out a powerful state through conquest of lands sought after by the Ethiopians and the European powers. The Dervish State successfully repulsed the British Empire four times and forced it to retreat to the coastal region.[37] Due to these successful expeditions, the Dervish State was recognised as an ally by the Ottoman and German empires. The Turks also named Hassan Emir of the Somali nation,[38] and the Germans promised to officially recognise any territories the Dervishes were to acquire.[39]

After a quarter of a century of holding the British at bay, the Dervishes were finally defeated in 1920 as a direct consequence of Britain's use of aircraft.[40]

Herero Wars and the Maji-Maji Rebellion

Between 1904 and 1908, Germany's colonies in German South-West Africa and German East Africa were rocked by separate, contemporaneous native revolts against their rule. In both territories the threat to German rule was quickly defeated once large-scale reinforcements from Germany arrived, with the Herero rebels in German South-West Africa being defeated at the Battle of Waterberg and the Maji-Maji rebels in German East Africa being steadily crushed by German forces slowly advancing through the countryside, with the natives resorting to guerrilla warfare. German efforts to clear the bush of civilians in German South-West Africa then resulted in a genocide of the population.

In total, as many as 65,000 Herero (80% of the total Herero population), and 10,000 Namaqua (50% of the total Namaqua population) either starved, died of thirst, or were worked to death in camps such as Shark Island Concentration Camp between 1904 and 1908. Characteristic of this genocide was death by starvation and the poisoning of the population's wells whilst they were trapped in the Namib Desert.

Colonial encounter

Colonial consciousness and exhibitions

Colonial lobby

Pygmies and a European. Some pygmies would be exposed in human zoos, such as Ota Benga displayed by eugenicist Madison Grant in the Bronx Zoo.

In its earlier stages, imperialism was generally the act of individual explorers as well as some adventurous merchantmen. The colonial powers were a long way from approving without any dissent the expensive adventures carried out abroad. Various important political leaders, such as Gladstone, opposed colonisation in its first years. However, during his second premiership between 1880 and 1885 he could not resist the colonial lobby in his cabinet, and thus did not execute his electoral promise to disengage from Egypt. Although Gladstone was personally opposed to imperialism, the social tensions caused by the Long Depression pushed him to favor jingoism: the imperialists had become the "parasites of patriotism" (John A. Hobson).[41] In France, then Radical politician Georges Clemenceau also adamantly opposed himself to it: he thought colonisation was a diversion from the "blue line of the Vosges" mountains, that is revanchism and the patriotic urge to reclaim the Alsace-Lorraine region which had been annexed by the German Empire with the 1871 Treaty of Frankfurt. Clemenceau actually made Jules Ferry's cabinet fall after the 1885 Tonkin disaster. According to Hannah Arendt in The Origins of Totalitarianism (1951), this expansion of national sovereignty on overseas territories contradicted the unity of the nation state which provided citizenship to its population. Thus, a tension between the universalist will to respect human rights of the colonised people, as they may be considered as "citizens" of the nation state, and the imperialist drive to cynically exploit populations deemed inferior began to surface. Some, in colonising countries, opposed what they saw as unnecessary evils of the colonial administration when left to itself; as described in Joseph Conrad's Heart of Darkness (1899)—published around the same time as Kipling's The White Man's Burden—or in Louis-Ferdinand Céline's Journey to the End of the Night (1932).

Colonial lobbies emerged to legitimise the Scramble for Africa and other expensive overseas adventures. In Germany, France, and Britain, the middle class often sought strong overseas policies to ensure the market's growth. Even in lesser powers, voices like Enrico Corradini claimed a "place in the sun" for so-called "proletarian nations", bolstering nationalism and militarism in an early prototype of fascism.

Colonial propaganda and jingoism

Colonial exhibitions

Poster for the 1906 Colonial Exhibition in Marseilles (France)

However, by the end of World War I the colonial empires had become very popular almost everywhere in Europe: public opinion had been convinced of the needs of a colonial empire, although most of the metropolitans would never see a piece of it. Colonial exhibitions had been instrumental in this change of popular mentalities brought about by the colonial propaganda, supported by the colonial lobby and by various scientists. Thus, the conquest of territories were inevitably followed by public displays of the indigenous people for scientific and leisure purposes. Karl Hagenbeck, a German merchant in wild animals and a future entrepreneur of most Europeans zoos, thus decided in 1874 to exhibit Samoa and Sami people as "purely natural" populations. In 1876, he sent one of his collaborators to the newly conquered Egyptian Sudan to bring back some wild beasts and Nubians. Presented in Paris, London, and Berlin these Nubians were very successful. Such "human zoos" could be found in Hamburg, Antwerp, Barcelona, London, Milan, New York City, Paris, etc., with 200,000 to 300,000 visitors attending each exhibition. Tuaregs were exhibited after the French conquest of Timbuktu (visited by René Caillié, disguised as a Muslim, in 1828, thereby winning the prize offered by the French Société de Géographie); Malagasy after the occupation of Madagascar; Amazons of Abomey after Behanzin's mediatic defeat against the French in 1894. Not used to the climatic conditions, some of the indigenous exposed died, such as some Galibis in Paris in 1892.[42]

Geoffroy de Saint-Hilaire, director of the Parisian Jardin d'acclimatation, decided in 1877 to organise two "ethnological spectacles", presenting Nubians and Inuit. The public of the Jardin d'acclimatation doubled, with a million paying entrances that year, a huge success for these times. Between 1877 and 1912, approximately thirty "ethnological exhibitions" were presented at the Jardin zoologique d'acclimatation.[43] "Negro villages" would be presented in Paris' 1878 and 1879 World's Fair; the 1900 World's Fair presented the famous diorama "living" in Madagascar, while the Colonial Exhibitions in Marseilles (1906 and 1922) and in Paris (1907 and 1931) would also display human beings in cages, often nudes or quasi-nudes.[44] Nomadic "Senegalese villages" were also created, thus displaying the power of the colonial empire to all the population.

In the US, Madison Grant, head of the New York Zoological Society, exposed Pygmy Ota Benga in the Bronx Zoo alongside the apes and others in 1906. At the behest of Grant, a prominent scientific racist and eugenicist, zoo director Hornaday placed Ota Benga in a cage with an orangutan and labeled him "The Missing Link" in an attempt to illustrate Darwinism, and in particular that Africans like Ota Benga are closer to apes than were Europeans. Other colonial exhibitions included the 1924 British Empire Exhibition and the successful 1931 Paris "Exposition coloniale".

Countering disease

From the beginning of the 20th century onward, the elimination or control of disease in tropical countries became a driving force for all colonial powers.[45] The sleeping sickness epidemic in Africa was arrested due to mobile teams systematically screening millions of people at risk.[46] In the 20th century, Africa saw the biggest increase in its population due to lessening of the mortality rate in many countries due to peace, famine relief, medicine, and above all, the end or decline of the slave trade.[47] Africa's population has grown from 120 million in 1900[48] to over 1 billion today.[49]Slavery abolition

The continuing anti-slavery movement in Europe became a reason and an excuse for the conquest and colonization of the Africa. It was the central theme of the Brussels Anti-Slavery Conference 1889-90. During the Scramble for Africa, an early but secondary focus of all colonial regimes was the suppression of slavery and the slave trade. In French West Africa, following conquest and abolition by the French, over a million slaves fled from their masters to earlier homes between 1906 and 1911. In Madagascar, the French abolished slavery in 1896 and approximately 500,000 slaves were freed. Slavery was abolished in the French controlled Sahel by 1911. Independent nations attempting to westernize or impress Europe sometimes cultivated an image of slavery suppression. In response to European pressure, the Sokoto Caliphate abolished slavery in 1900 and Ethiopia officially abolished slavery in 1932. Colonial powers were mostly successful in abolishing slavery, though slavery remained active in Africa even though it has gradually moved to a wage economy. Slavery was never fully eradicated in Africa.Colonialism leading to World War I

German Cameroon, painting by R. Hellgrewe, 1908

During the New Imperialism period, by the end of the 19th century, Europe added almost 9,000,000 square miles (23,000,000 km2) – one-fifth of the land area of the globe – to its overseas colonial possessions. Europe's formal holdings now included the entire African continent except Ethiopia, Liberia, and Saguia el-Hamra, the latter of which would be integrated into Spanish Sahara. Between 1885 and 1914, Britain took nearly 30% of Africa's population under its control; 15% for France, 11% for Portugal, 9% for Germany, 7% for Belgium and 1% for Italy.[citation needed] Nigeria alone contributed 15 million subjects, more than in the whole of French West Africa or the entire German colonial empire. It was paradoxical that Britain, the staunch advocate of free trade, emerged in 1914 with not only the largest overseas empire thanks to its long-standing presence in India, but also the greatest gains in the "scramble for Africa", reflecting its advantageous position at its inception. In terms of surface area occupied, the French were the marginal victors but much of their territory consisted of the sparsely populated Sahara.

The political imperialism followed the economic expansion, with the "colonial lobbies" bolstering chauvinism and jingoism at each crisis in order to legitimise the colonial enterprise. The tensions between the imperial powers led to a succession of crises, which finally exploded in August 1914, when previous rivalries and alliances created a domino situation that drew the major European nations into World War I. Austria-Hungary attacked Serbia to avenge the murder by Serbian agents of Austrian crown prince Francis Ferdinand, Russia would mobilise to assist allied Serbia, Germany would intervene to support Austria-Hungary against Russia. Since Russia had a military alliance with France against Germany, the German General Staff, led by General von Moltke decided to realise the well prepared Schlieffen Plan to invade and quickly knock France out of the war before turning against Russia in what was expected to be a long campaign. This required an invasion of Belgium which brought Britain into the war against Germany, Austria-Hungary and their allies. German U-Boat campaigns against ships bound for Britain eventually drew the United States into what had become World War I. Moreover, using the Anglo-Japanese Alliance as an excuse, Japan leaped onto this opportunity to conquer German interests in China and the Pacific to become the dominating power in the Western Pacific, setting the stage for the Second Sino-Japanese War (starting in 1937) and eventually World War II.

African colonies listed by colonising power

Belgium

- Congo Free State and Belgian Congo (today's Democratic Republic of the Congo)

- Ruanda-Urundi (comprising modern Rwanda and Burundi, 1922–62)

France

|

|

|

|

The Senegalese Tirailleurs, led by Colonel Alfred-Amédée Dodds, conquered Dahomey (present-day Benin) in 1892

Germany

- German Kamerun (now Cameroon and part of Nigeria, 1884–1916)

- German East Africa (now Rwanda, Burundi and most of Tanzania, 1885–1919)

- German South-West Africa (now Namibia, 1884–1915)

- German Togoland (now Togo and eastern part of Ghana, 1884–1914)

Italy

Later, during the Interwar period, with the Second Italo-Ethiopian War Italy would annex Ethiopia, which formed together with Eritrea and Italian Somaliland the Italian East Africa (A.O.I., "Africa Orientale Italiana", also defined by the fascist government as L'Impero).Portugal

Marracuene in Portuguese Mozambique was the site of a decisive battle between Portuguese and Gaza king Gungunhana in 1895

|

Spain

|

|

United Kingdom

Opening of the railway in Rhodesia, 1899

Following the Fourth Anglo-Ashanti War in 1896, the British proclaimed a protectorate over the Ashanti Kingdom.

The British were primarily interested in maintaining secure communication lines to India, which led to initial interest in Egypt and South Africa. Once these two areas were secure, it was the intent of British colonialists such as Cecil Rhodes to establish a Cape-Cairo railway and to exploit mineral and agricultural resources. Control of the Nile was viewed as a strategic and commercial advantage.

|

|

Independent states

Liberia was the only nation in Africa that was a colony and a protectorate of the United States. Liberia was founded, colonised, established and controlled by the American Colonization Society, a private organisation established in order to relocate freed African-American and Caribbean slaves from the United States and the Caribbean islands in 1821. Liberia declared its independence from the American Colonization Society on July 26, 1847. Liberia is Africa's oldest democratic republic, and the second-oldest black republic in the world (after Haiti).Ethiopia maintained its independence from Italy after the Battle of Adwa which resulted in the Treaty of Addis Ababa. With the exception of the occupation between 1936 and 1941 by Benito Mussolini's military forces, Ethiopia is Africa's oldest independent nation.

Modern Scramble for Africa

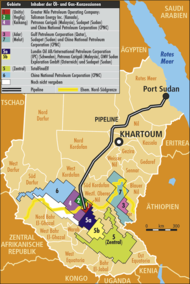

Oil and gas concessions in Sudan – 2004

The new scramble for Africa began with the emergence of the Afro-Neo-Liberal capitalist movement in Post-Colonial Africa.[55] When African nations began to gain independence during the Post World War II Era, their post colonial economic structures remained undiversified and linear. In most cases, the bulk of a nation’s economy relied on cash crops or natural resources. The decolonisation process kept independent African nations at the mercy of colonial powers due to structurally-dependent economic relations. Structural adjustment programs led to the privatization and liberalization of many African political and economic systems, forcefully pushing Africa into the global capitalist market. The economic decline in the 1990s fostered democratization by the World Bank intervening in the political and economic affairs of Africa once again.All of these factors led to Africa’s forced development under Western ideological systems of economics and politics.[56]