Fluorosulfuric acid-antimony pentafluoride 1:1

| |

| Identifiers | |

|---|---|

3D model (JSmol)

|

|

| ChemSpider | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.041.727 |

PubChem CID

|

|

| Properties | |

| HSbF6SO3 | |

| Molar mass | 316.82 g/mol |

| Appearance | Liquid |

| Hazards | |

| R-phrases (outdated) | R14 R15/29 R16 R17 R18 R19 R26/27/28 R30 R31 R32 R33 R34 |

| S-phrases (outdated) | S26 S27 S36/37/39 S38 S40 S41 S42 S43 S45 |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |

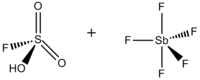

Magic acid (FSO3H·SbF5) is a superacid consisting of a mixture, most commonly in a 1:1 molar ratio, of fluorosulfuric acid (HSO3F) and antimony pentafluoride (SbF5). This conjugate Brønsted–Lewis superacid system was developed in the 1960s by the George Olah lab at Case Western Reserve University, and has been used to stabilize carbocations and hypercoordinated carbonium ions in liquid media. Magic acid and other superacids are also used to catalyze isomerization of saturated hydrocarbons, and have been shown to protonate even weak bases, including methane, xenon, halogens, and molecular hydrogen.

History

The term "superacid" was first used in 1927 when James Bryant Conant found that perchloric acid could protonate ketones and aldehydes to form salts in nonaqueous solution. The term itself was coined by Gillespie later, after Conant combined sulfuric acid with fluorosulfuric acid, and found the solution to be several million times more acidic than sulfuric acid alone.

The magic acid system was developed in the 1960s by George Olah, and

was to be used to study stable carbocations. Gillespie also used the

acid system to generate electron-deficient inorganic cations. The name

originated after a Christmas party in 1966, when a member of the Olah

lab placed a paraffin candle into the acid, and found that it dissolved quite rapidly. Examination of the solution with 1H-NMR showed a tert-butyl

cation, suggesting that the paraffin chain that forms the wax had been

cleaved, then isomerized, and the atoms were arranged into a different

shape to form the ion. The name appeared in a paper published by the Olah lab.

Properties

Structure

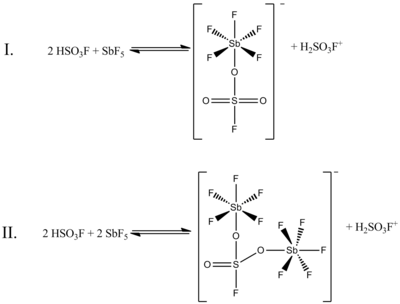

Although a 1:1 molar ratio of HSO3F and SbF5 best generates carbonium ions, the effects of the system at other molar ratios have also been documented. When the ratio SbF5:HSO3F is less than 0.2, the following two equilibria, determined by 19F NMR spectroscopy, are the most prominent in solution:

(In both of these structures, the sulfur has tetrahedral

coordination, not planar. The double bonds between sulfur and oxygen are

more properly represented as single bonds, with formal

negative charges on the oxygen atoms and a formal plus two charge on

the sulfur. The antimony atoms will also have a formal charge of minus

one.)

In the above figure, Equilibrium I accounts for 80% of the NMR

data, while Equilibrium II accounts for about 20%. As the ratio of the

two compounds increases from 0.4–1.4, new NMR signals appear and

increase in intensity with increasing concentrations of SbF5. The resolution of the signals decreases as well, because of the increasing viscosity of the liquid system.

Strength

All

proton-producing acids stronger than 100% sulfuric acid are considered

superacids, and are characterized by low values of the Hammett acidity function. For instance, sulfuric acid, H2SO4, has a Hammett acidity function, H0, of −12, perchloric acid, HClO4, has a Hammett acidity function, of −13, and that of the 1:1 magic acid system, HSO3F·SbF5, is −23. Fluoroantimonic acid, the strongest known superacid, can reach up to H0 = −28.

Uses

Observations of stable carbocations

Magic

acid has low nucleophilicity, allowing for increased stability of

carbocations in solution. The "classical" trivalent carbocation can be

observed in the acid medium, and has been found to be planar and sp2-hybridized.

Because the carbon has only six valence electrons, it is highly

electron deficient and electrophilic. It is easily described by Lewis dot structures

because it contains only two-electron, two-carbon bonds. Many tertiary

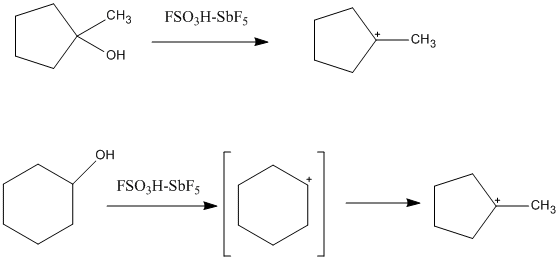

cycloalkyl cations can also be formed in superacidic solutions. One such

example is the 1-methyl-1-cyclopentyl cation, which is formed from both

the cyclopentane and cyclohexane precursor. In the case of the cyclohexane,

the cyclopentyl cation is formed from isomerization of the secondary

carbocation to the tertiary, more stable carbocation.

Cyclopropylcarbenium ions, alkenyl cations, and arenium cations have

also been observed.

As use of the Magic acid system became more widespread, however,

higher-coordinate carbocations were observed. Penta-coordinate

carbocations, also described as nonclassical ions,

cannot be depicted using only two-electron, two-center bonds, and

require, instead, two-electron, three (or more) center bonding. In

these ions, two electrons are delocalized over more than two atoms,

rendering these bond centers so electron deficient that they enable

saturated alkanes to participate in electrophilic reactions.

The discovery of hypercoordinated carbocations fueled the nonclassical

ion controversy of the 1950s and 60s. Due to the slow timescale of 1H-NMR, the rapidly equilibrating positive charges on hydrogen atoms would likely go undetected. However, IR spectroscopy, Raman spectroscopy, and 13C

NMR have been used to investigate bridged carbocation systems. One

controversial cation, the norbornyl cation, has been observed in several

media, Magic acid among them.

The bridging methylene carbon atom is pentacoordinated, with three

two-electron, two-center bonds, and one two-electron, three-center bond

with its remaining sp3 orbital. Quantum mechanical calculations have also shown that the classical model is not an energy minimum.

Reactions with alkanes

Magic acid is capable of protonating alkanes. For instance, methane reacts to form the CH+

5 ion at 140 °C and atmospheric pressure, though some hydrocarbon ions of greater molecular weights are also formed as byproducts. Hydrogen gas is another reaction byproduct.

5 ion at 140 °C and atmospheric pressure, though some hydrocarbon ions of greater molecular weights are also formed as byproducts. Hydrogen gas is another reaction byproduct.

In the presence of FSO3D rather than FSO3H, methane has been shown to interchange hydrogen atoms for deuterium atoms, and HD is released rather than H2.

This is evidence to suggest that in these reactions, methane is indeed a

base, and can accept a proton from the acid medium to form CH+

5. This ion is then deprotonated, explaining the hydrogen exchange, or loses a hydrogen molecule to form CH+

3 – the carbonium ion. This species is quite reactive, and can yield several new carbocations, shown below.

5. This ion is then deprotonated, explaining the hydrogen exchange, or loses a hydrogen molecule to form CH+

3 – the carbonium ion. This species is quite reactive, and can yield several new carbocations, shown below.

Larger alkanes, such as ethane, are also reactive in magic acid, and

both exchange hydrogen atoms and condense to form larger carbocations,

such as protonated neopentane. This ion is then cloven at higher

temperatures, and reacts to release hydrogen gas and forms the t-amyl

cation at lower temperatures.

It is on this note that George Olah suggests we no longer take as

synonymous the names "alkane" and "paraffin." The word "paraffin" is

derived from the Latin "parum affinis", meaning "lacking in affinity."

He says, "It is, however, with some nostalgia that we make this

recommendation, as ‘inert gases’ at least maintained their ‘nobility’ as

their chemical reactivity became apparent, but referring to ‘noble

hydrocarbons’ would seem to be inappropriate."

Catalysis with hydroperoxides

Magic

acid catalyzes cleavage-rearrangement reactions of tertiary

hydroperoxides and tertiary alcohols. The nature of the experiments used

to determine the mechanism, namely the fact that they took place in

superacid medium, allowed observation of the carbocation intermediates

formed. It was determined that the mechanism depends on the amount of

magic acid used. Near molar equivalency, only O–O cleavage is observed,

but with increasing excess of magic acid, C–O cleavage competes with O–O

cleavage. The excess acid likely deactivates the hydrogen peroxide

formed in C–O heterolysis.

Magic acid also catalyzes electrophilic hydroxylation of aromatic

compounds with hydrogen peroxide, resulting in high-yield preparation of

monohydroxylated products. Phenols exist as completely protonated

species in superacid solutions, and when produced in the reaction, are

then deactivated toward further electrophilic attack. Protonated

hydrogen peroxide is the active hydroxylating agent.

Catalysis with ozone

Oxygenation of alkanes can be catalyzed by a magic acid–SO2ClF solution in the presence of ozone.

The mechanism is similar to that of protolysis of alkanes, with an

electrophilic insertion into the single σ bonds of the alkane. The

hydrocarbon–ozone complex transition state has the form of a

penta-coordinated ion.

Alcohols, ketones, and aldehydes are oxygenated by electrophilic insertion as well.

Safety

As with all

strong acids, and especially superacids, proper personal protective

equipment should be used. In addition to the obligatory gloves and

goggles, the use of a faceshield and full-face respirator are also

recommended. Predictably, magic acid is highly toxic upon ingestion and

inhalation, causes severe skin and eye burns, and is toxic to aquatic

life.

![{\displaystyle v_{e}={\sqrt {\,{\frac {T\,R}{M}}\cdot {\frac {2\;\gamma }{\gamma -1}}\cdot \left[1-\left({\frac {p_{e}}{p}}\right)^{\frac {\gamma -1}{\gamma }}\right]}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/ef1daa8ee24795de2b8ab6cb7b657044846bf03f)

![{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}F&={\dot {m}}v_{\text{e}}+\left(p_{\text{e}}-p_{\text{o}}\right)A_{e}\\[2pt]&={\dot {m}}\left[v_{\text{e}}+\left({\frac {p_{\text{e}}-p_{\text{o}}}{\dot {m}}}\right)A_{\text{e}}\right],\end{aligned}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/7619ecb93fcd122ee9ac8f8caffa0c468f23f77c)