From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

|

Headquarters of Médecins sans frontières international in Geneva

|

| Founded | 20 December 1971 |

|---|

| Founders | Jacques Bérès

Philippe Bernier

Raymond Borel

Jean Cabrol

Marcel Delcourt

Xavier Emmanuelli

Pascal Grellety Bosviel

Gérard Illiouz Bernard Kouchner

Gérard Pigeon Vladan Radoman

Max Récamier

Jean-Michel Wild |

|---|

| Type | Medical humanitarian organisation |

|---|

| Location |

|

|---|

Area served

| Worldwide |

|---|

Key people

| Joanne Liu (MSF International President) |

|---|

Employees

| 36,482 |

|---|

| Website | msf.org |

|---|

Médecins Sans Frontières (

MSF; pronounced

[medsɛ̃ sɑ̃ fʁɔ̃tjɛʁ]), sometimes rendered in English as

Doctors Without Borders, is an international

humanitarian medical

non-governmental organisation (NGO) of French origin best known for its projects in conflict zones and in

countries affected by

endemic diseases.

In 2015, over 30,000 personnel — mostly local doctors, nurses and other

medical professionals, logistical experts, water and sanitation

engineers and administrators — provided medical aid in over 70

countries.

Most staff are volunteers. Private donors provide about 90% of the

organisation's funding, while corporate donations provide the rest,

giving MSF an annual budget of approximately US$1.63 billion.

Médecins sans frontières was founded in 1971, in the aftermath of the

Biafra secession, by a small group of French doctors and journalists who sought to expand accessibility to

medical care across national boundaries and irrespective of

race,

religion, creed or political affiliation.

To that end, the organisation emphasises "independence and

impartiality", and explicitly precludes political, economic, or

religious factors in its decision making. For these reasons, it limits

the amount of funding received from governments or intergovernmental

organisation. These principles have allowed MSF to speak freely with

respect to acts of war, corruption, or other hindrances to medical care

or human well-being. Only once in its history, during the

1994 genocide in Rwanda, has the organisation called for military intervention.

MSF's principles and operational guidelines are highlighted in its Charter, the Chantilly Principles, and the later La Mancha Agreement.

Governance is addressed in Section 2 of the Rules portion of this final

document. MSF has an associative structure, where operational decisions

are made, largely independently, by the five operational centres (

Amsterdam,

Barcelona-

Athens,

Brussels,

Geneva and

Paris).

Common policies on core issues are coordinated by the International

Council, in which each of the 24 sections (national offices) is

represented. The International Council meets in

Geneva,

Switzerland, where the International Office, which coordinates

international activities common to the operational centres, is also

based.

MSF has

general consultative status with the United Nations Economic and Social Council. It received the 1999

Nobel Peace Prize

in recognition of its members' continued efforts to provide medical

care in acute crises, as well as raising international awareness of

potential humanitarian disasters.

James Orbinski,

who was the president of the organization at the time, accepted the

prize on behalf of MSF. Prior to this, MSF also received the 1996

Seoul Peace Prize.

Joanne Liu has served as the international president since 1 October 2013.

MSF should not be confused with

Médecins du Monde

(Doctors of the World), which was formed in part by members of the

former organisation, but is an entirely independent non-governmental

organisation with no links to MSF today.

Origin

Biafra

During the

Nigerian Civil War of 1967 to 1970, the Nigerian military formed a

blockade around the nation's newly

independent south-eastern region,

Biafra. At this time, France was the only major country supportive of the Biafrans (the United Kingdom, the

Soviet Union

and the United States sided with the Nigerian government), and the

conditions within the blockade were unknown to the world. A number of

French doctors volunteered with the French

Red Cross to work in hospitals and feeding centres in besieged Biafra. One of the co-founders of the organisation was

Bernard Kouchner, who later became a high-ranking French politician.

After entering the country, the volunteers, in addition to Biafran

health workers and hospitals, were subjected to attacks by the

Nigerian army,

and witnessed civilians being murdered and starved by the blockading

forces. The doctors publicly criticised the Nigerian government and the

Red Cross for their seemingly complicit behaviour. These doctors

concluded that a new aid organisation was needed that would ignore

political/religious boundaries and prioritise the welfare of victims.

1971 establishment

The

Groupe d'intervention médicale et chirurgicale en urgence

("Emergency Medical and Surgical Intervention Group") was formed in

1971 by French doctors who had worked in Biafra, to provide aid and to

emphasize the importance of victims' rights over neutrality. At the same

time,

Raymond Borel, the editor of the French

medical journal TONUS, had started a group called

Secours Médical Français ("French Medical Relief") in response to the

1970 Bhola cyclone, which killed at least 625,000 in

East Pakistan

(now Bangladesh). Borel had intended to recruit doctors to provide aid

to victims of natural disasters. On 22 December 1971, the two groups of

colleagues merged to form

Médecins Sans Frontières.

MSF's first mission was to the Nicaraguan capital,

Managua, where a

1972 earthquake had destroyed most of the city and killed between 10,000 and 30,000 people.

The organization, today known for its quick response in an emergency,

arrived three days after the Red Cross had set up a relief mission. On

18 and 19 September 1974,

Hurricane Fifi

caused major flooding in Honduras and killed thousands of people

(estimates vary), and MSF set up its first long-term medical relief

mission.

Between 1975 and 1979, after

South Vietnam had fallen to

North Vietnam, millions of Cambodians emigrated to Thailand to avoid the

Khmer Rouge. In response MSF set up its first

refugee camp missions in Thailand. When Vietnam withdrew from Cambodia in 1989, MSF started long-term relief missions to help survivors of

the mass killings and reconstruct the country's health care system. Although its missions to Thailand to help victims of war in Southeast

Asia could arguably be seen as its first war-time mission, MSF saw its

first mission to a true war zone, including exposure to hostile fire, in

1976. MSF spent nine years (1976–1984) assisting surgeries in the

hospitals of various cities in Lebanon, during the

Lebanese Civil War, and established a reputation for its neutrality and willingness to work under fire. Throughout the war, MSF helped both

Christian and

Muslim soldiers

alike, helping whichever group required the most medical aid at the

time. In 1984, as the situation in Lebanon deteriorated further and

security for aid groups was minimised, MSF withdrew its volunteers.

New leadership

Claude Malhuret

was elected as the new president of Medicins Sans Frontieres in 1977,

and soon after debates began over the future of the organisation. In

particular, the concept of

témoignage ("witnessing"), which refers to speaking out about the suffering that one sees as opposed to remaining silent,

was being opposed or played down by Malhuret and his supporters.

Malhuret thought MSF should avoid criticism of the governments of

countries in which they were working, while Kouchner believed that

documenting and broadcasting the suffering in a country was the most

effective way to solve a problem.

In 1979, after four years of refugee movement from South Vietnam and the surrounding countries by foot and

by boat, French intellectuals made an appeal in

Le Monde

for "A Boat for Vietnam", a project intended to provide medical aid to

the refugees. Although the project did not receive support from the

majority of MSF, some, including later Minister

Bernard Kouchner, chartered a ship called

L’Île de Lumière ("The Island of Light"), and, along with doctors, journalists and photographers, sailed to the

South China Sea and provided some medical aid to the boat people. The splinter organisation that undertook this,

Médecins du Monde, later developed the idea of

humanitarian intervention as a duty, in particular on the part of Western nations such as France.

In 2007 MSF clarified that for nearly 30 years MSF and Kouchner have

had public disagreements on such issues as the right to intervene and

the use of armed force for humanitarian reasons. Kouchner is in favour

of the latter, whereas MSF stands up for an impartial humanitarian

action, independent from all political, economic and religious powers.

MSF development

In 1982, Malhuret and

Rony Brauman

(who became the organisation's president in 1982) brought increased

financial independence to MSF by introducing fundraising-by-mail to

better collect donations. The 1980s also saw the establishment of the

other operational sections from MSF-France (1971): MSF-Belgium (1980),

MSF-Switzerland (1981), MSF-Holland (1984), and MSF-Spain (1986).

MSF-Luxembourg was the first support section, created in 1986. The early

1990s saw the establishment of the majority of the support sections:

MSF-Greece (1990), MSF-USA (1990), MSF-Canada (1991), MSF-Japan (1992),

MSF-UK (1993), MSF-Italy (1993), MSF-Australia (1994), as well as

Germany, Austria, Denmark, Sweden, Norway, and Hong Kong (MSF-UAE was

formed later). Malhuret and Brauman were instrumental in professionalising MSF. In December 1979, after the

Soviet army had invaded Afghanistan, field missions were immediately set up to provide medical aid to the

mujahideen, and in February 1980, MSF publicly denounced the

Khmer Rouge. During the

1983–1985 famine in Ethiopia,

MSF set up nutrition programmes in the country in 1984, but was

expelled in 1985 after denouncing the abuse of international aid and the

forced resettlements. MSF's explicit attacks on the Ethiopian

government led to other NGOs criticizing their abandonment of their

supposed neutrality and contributed to a series of debates in France

around humanitarian ethics. The group also set up equipment to produce clean

drinking water for the population of

San Salvador, capital of El Salvador, after 10 October 1986 earthquake that struck the city. In 2014, the

European Speedster Assembly had contributed $717,000 to MSF.

Sudan

Since 1979, MSF has been providing medical humanitarian assistance in

Sudan, a nation plagued by starvation and the

civil war,

prevalent malnutrition and one of the highest maternal mortality rates

in the world. In March 2009, it is reported that MSF has employed 4,590

field staff in Sudan

tackling issues such as armed conflicts, epidemic diseases, health care

and social exclusion. MSF's continued presence and work in

Sudan

is one of the organization's largest interventions. MSF provides a

range of health care services including nutritional support,

reproductive healthcare, Kala-Azar treatment, counselling services and

surgery to the people living in

Sudan. Common diseases prevalent in

Sudan include

tuberculosis,

kala-azar also known as

visceral leishmaniasis,

meningitis,

measles,

cholera, and

malaria.

Kala-Azar in Sudan

Kala-azar, also known as

visceral leishmaniasis, has been one of the major health problems in

Sudan.

After the Comprehensive Peace Agreement between North and Southern

Sudan on 9 January 2005, the increase in stability within the region

helped further efforts in healthcare delivery. Médicins sans Frontières

tested a combination of sodium stibogluconate and paromomycin, which

would reduce treatment duration (from 30 to 17 days) and cost in 2008.

In March 2010, MSF set up its first Kala-Azar treatment centre in

Eastern Sudan, providing free treatment for this otherwise deadly

disease. If left untreated, there is a fatality rate of 99% within 1–4

months of infection. Since the treatment centre was set up, MSF has cured more than 27,000

Kala-Azar patients with a success rate of approximately 90–95%. There are plans to open an additional Kala-Azar treatment centre in

Malakal,

Southern Sudan

to cope with the overwhelming number of patients that are seeking

treatment. MSF has been providing necessary medical supplies to

hospitals and training Sudanese health professionals to help them deal

with

Kala-Azar.

MSF, Sudanese Ministry of Health and other national and international

institutions are combining efforts to improve on the treatment and

diagnosis of Kala-Azar. Research on its cures and vaccines are currently being conducted. In December 2010, South Sudan was hit with the worst outbreak of Kala-Azar in eight years. The number of patients seeking treatment increased eight-fold as compared to the year before.

Health care infrastructure in Sudan

Sudan's latest civil war began in 1983 and ended in 2005 when a peace agreement was signed between

North Sudan and

South Sudan.

MSF medical teams were active throughout and prior to the civil war,

providing emergency medical humanitarian assistance in multiple

locations.

The situation of poor infrastructure in the South was aggravated by the

civil war and resulted in the worsening of the region's appalling

health indicators. An estimated 75 percent of people in the nascent

nation has no access to basic medical care and 1 in seven women dies

during childbirth.

Malnutrition and disease outbreaks are perennial concerns as well. In 2011, MSF clinic in

Jonglei State,

South Sudan was looted and attacked by raiders.

Hundreds, including women and children were killed. Valuable items

including medical equipment and drugs were lost during the raid and

parts of the MSF facilities were destroyed in a fire. The incident had serious repercussions as MSF is the only primary health care provider in this part of

Jonglei State.

Early 1990s

The

early 1990s saw MSF open a number of new national sections, and at the

same time, set up field missions in some of the most dangerous and

distressing situations it had ever encountered.

In 1990, MSF first entered Liberia to help civilians and refugees affected by the

Liberian Civil War. Constant fighting throughout the 1990s and the

Second Liberian Civil War

have kept MSF volunteers actively providing nutrition, basic health

care, and mass vaccinations, and speaking out against attacks on

hospitals and feeding stations, especially in

Monrovia.

Field missions were set up to provide relief to

Kurdish refugees who had survived the

al-Anfal Campaign, for which evidence of atrocities was being collected in 1991. 1991 also saw the beginning of the

civil war in

Somalia,

during which MSF set up field missions in 1992 alongside a UN

peacekeeping mission. Although the UN-aborted operations by 1993, MSF

representatives continued with their relief work, running clinics and

hospitals for civilians.

MSF first began work in

Srebrenica (in Bosnia and Herzegovina) as part of a UN convoy in 1993, one year after the

Bosnian War had begun. The city had become surrounded by the

Bosnian Serb Army and, containing about 60,000

Bosniaks, had become an enclave guarded by a

United Nations Protection Force.

MSF was the only organisation providing medical care to the surrounded

civilians, and as such, did not denounce the genocide for fear of being

expelled from the country (it did, however, denounce the lack of access

for other organisations). MSF was forced to leave the area in 1995 when

the

Bosnian Serb Army captured the town. 40,000

Bosniak civilian inhabitants were deported, and approximately 7,000 were killed in mass executions.

Rwanda

When the

genocide in Rwanda began in April 1994, some delegates of MSF working in the country were incorporated into the

International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) medical team for protection. Both groups succeeded in keeping all main hospitals in Rwanda's capital

Kigali

operational throughout the main period of the genocide. MSF, together

with several other aid organisations, had to leave the country in 1995,

although many MSF and ICRC volunteers worked together under the ICRC's

rules of engagement, which held that neutrality was of the utmost

importance. These events led to a debate within the organisation about

the concept of balancing neutrality of humanitarian aid workers against

their witnessing role. As a result of its Rwanda mission, the position

of MSF with respect to neutrality moved closer to that of the ICRC, a

remarkable development in the light of the origin of the organisation.

The ICRC lost 56 and MSF lost almost one hundred of their respective

local staff in Rwanda, and MSF-France, which had chosen to evacuate its

team from the country (the local staff were forced to stay), denounced

the murders and demanded that a

French military intervention stop the genocide. MSF-France introduced the slogan

"One cannot stop a genocide with doctors" to the media, and the controversial

Opération Turquoise followed less than one month later. This intervention directly or indirectly resulted in movements of hundreds of thousands of Rwandan refugees to

Zaire and Tanzania in what became known as the

Great Lakes refugee crisis,

and subsequent cholera epidemics, starvation and more mass killings in

the large groups of civilians. MSF-France returned to the area and

provided medical aid to refugees in

Goma.

At the time of the genocide, competition between the medical

efforts of MSF, the ICRC, and other aid groups had reached an all-time

high, but the conditions in Rwanda prompted a drastic change in the way humanitarian organisations approached aid missions. The

Code of Conduct for the International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement and NGOs in Disaster Relief Programmes was created by the ICRC in 1994 to provide a framework for humanitarian missions and MSF is a signatory of this code.

The code advocates the provision of humanitarian aid only, and groups

are urged not to serve any political or religious interest, or be used

as a tool for foreign governments. MSF has since still found it necessary to condemn the actions of governments, such as in

Chechnya in 1999, but has not demanded another military intervention since then.

Sierra Leone

In the late 1990s, MSF missions were set up to treat tuberculosis and

anaemia in residents of the

Aral Sea area, and look after civilians affected by drug-resistant disease, famine, and epidemics of cholera and AIDS. They vaccinated 3 million Nigerians against

meningitis during an epidemic in 1996 and denounced the

Taliban's neglect of health care for women in 1997.

Arguably, the most significant country in which MSF set up field

missions in the late 1990s was Sierra Leone, which was involved in a

civil war at the time. In 1998, volunteers began assisting in surgeries in

Freetown to help with an increasing number of

amputees, and collecting statistics on civilians (men, women and children) being attacked by large groups of men claiming to represent

ECOMOG.

The groups of men were travelling between villages and systematically

chopping off one or both of each resident's arms, raping women, gunning

down families, razing houses, and forcing survivors to leave the area. Long-term projects following the end of the civil war included psychological support and

phantom limb pain management.

Ongoing missions

Countries where MSF had missions in 2015.

The

Campaign for Access to Essential Medicines was created in late 1999, providing MSF with a new voice with which to bring awareness to the lack of effective treatments and

vaccines

available in developing countries. In 1999, the organisation also spoke

out about the lack of humanitarian support in Kosovo and Chechnya,

having set up field missions to help civilians affected by the

respective political situations. Although MSF had worked in the Kosovo

region since 1993, the onset of the

Kosovo War

prompted the movement of tens of thousands of refugees, and a decline

in suitable living conditions. MSF provided shelter, water and health

care to civilians affected by

NATO's strategic bombing campaigns.

A serious crisis within MSF erupted in connection with the

organisation's work in Kosovo when the Greek section of MSF was expelled

from the organization. The Greek MSF section had gained access to

Serbia at the cost of accepting Serb government imposed limits on where

it could go and what it could see – terms that the rest of the MSF

movement had refused.

A non-MSF source alleged that the exclusion of the Greek section

happened because its members extended aid to both Albanian and Serbian

civilians in Pristina during NATO's bombing,

The rift was healed only in 2005 with the re-admission of the Greek section to MSF.

A similar situation was found in Chechnya, whose civilian

population was largely forced from their homes into unhealthy conditions

and subjected to the violence of the

Second Chechen War.

MSF has been working in Haiti since 1991, but since President

Jean-Bertrand Aristide

was forced from power, the country has seen a large increase in

civilian attacks and rape by armed groups. In addition to providing

surgical and psychological support in existing hospitals – offering the

only free surgery available in

Port-au-Prince

– field missions have been set up to rebuild water and waste management

systems and treat survivors of major flooding caused by

Hurricane Jeanne; patients with HIV/AIDS and malaria, both of which are widespread in the country, also receive better treatment and monitoring. As a result of 12 January

2010 Haiti earthquake,

reports from Haiti indicated that all three of the organisation's

hospitals had been severely damaged; one collapsing completely and the

other two having to be abandoned.

Following the quake, MSF sent about nine planes loaded with medical

equipment and a field hospital to help treat the victims. However, the

landings of some of the planes had to be delayed due to the massive

number of humanitarian and military flights coming in.

The

Kashmir Conflict in

northern India

resulted in a more recent MSF intervention (the first field mission was

set up in 1999) to help civilians displaced by fighting in

Jammu and Kashmir, as well as in

Manipur.

Psychological support is a major target of missions, but teams have

also set up programmes to treat tuberculosis, HIV/AIDS and malaria. Mental health support has been of significant importance for MSF in much of southern Asia since the

2004 Indian Ocean earthquake.

MSF went through a long process of self-examination and

discussion in 2005–2006. Many issues were debated, including the

treatment "nationals" as well as "fair employment" and self-criticism.

Africa

An MSF outpost in Darfur (2005)

MSF has been active in a large number of African countries for

decades, sometimes serving as the sole provider of health care, food,

and water. Although MSF has consistently attempted to increase media

coverage of the situation in Africa to increase international support,

long-term field missions are still necessary. Treating and educating the

public about

HIV/AIDS in

sub-Saharan Africa, which sees the most deaths and cases of the disease in the world,

is a major task for volunteers. Of the 14.6 million people in need of

anti-retroviral treatment the WHO estimated that only 5.25 million

people were receiving it in developing countries, and MSF continues to

urge governments and companies to increase research and development into

HIV/AIDS treatments to decrease cost and increase availability.

Although active in the Congo region of Africa since 1985, the

First and

Second Congo War brought increased violence and instability to the area. MSF has had to evacuate its teams from areas such as around

Bunia, in the Ituri district due to extreme violence,

but continues to work in other areas to provide food to tens of

thousands of displaced civilians, as well as treat survivors of mass

rapes and widespread fighting. The treatment and possible vaccination against diseases such as

cholera,

measles,

polio,

Marburg fever,

sleeping sickness,

HIV/AIDS, and

Bubonic plague is also important to prevent or slow down epidemics.

MSF has been active in Uganda since 1980, and provided relief to civilians during the country's guerrilla war during the

Second Obote Period. However, the formation of the

Lord's Resistance Army

saw the beginning of a long campaign of violence in northern Uganda and

southern Sudan. Civilians were subjected to mass killings and rapes,

torture, and abductions of children, who would later serve as sex slaves

or

child soldiers. Faced with more than 1.5 million people displaced from their homes, MSF set up relief programmes in

internally displaced person (IDP) camps to provide clean water, food and sanitation. Diseases such as

tuberculosis, measles, polio, cholera,

ebola,

and HIV/AIDS occur in epidemics in the country, and volunteers provide

vaccinations (in the cases of measles and polio) and/or treatment to the

residents. Mental health is also an important aspect of medical

treatment for MSF teams in Uganda since most people refuse to leave the

IDP camps for constant fear of being attacked.

MSF first camp set up a field mission in Côte d'Ivoire in 1990, but ongoing violence and the

2002 division

of the country by rebel groups and the government led to several

massacres, and MSF teams have even begun to suspect that an ethnic

cleansing is occurring. Mass measles vaccinations,

tuberculosis treatment and the re-opening of hospitals closed by

fighting are projects run by MSF, which is the only group providing aid

in much of the country.

During the Ebola outbreak in West Africa in 2014, MSF met serious

medical demands largely on its own, after the organisation's early

warnings were largely ignored.

In 2014 MSF partnered with satellite operator

SES, other NGOs Archemed, Fondation Follereau, Friendship Luxembourg and

German Doctors, and the

Luxembourg government in the pilot phase of

SATMED, a project to use

satellite broadband technology to bring

eHealth and

telemedicine to isolated areas of developing countries. SATMED was first deployed in Sierra Leone in support of the fight against Ebola.

Cambodia

MSF

first provided medical help to civilians and refugees who have escaped

to camps along the Thai-Cambodian border in 1979. Due to long decades of

war, a proper

health care system in the country was severely lacking and MSF moved inland in 1989 to help restructure basic medical facilities.

In 1999, Cambodia was hit with a malaria epidemic. The situation

of the epidemic was aggravated by a lack of qualified practitioners and

poor quality control which led to a market of fake antimalarial drugs.

Counterfeit antimalarial drugs were responsible for the deaths of at

least 30 people during the epidemic. This has prompted efforts by MSF to set up and fund a malaria outreach project and utilise Village Malaria Workers.

MSF also introduced a switching of first-line treatment to a

combination therapy (Artesunate and Mefloquine) to combat resistance and

fatality of old drugs that were used to treat the disease

traditionally.

Cambodia is one of the hardest hit HIV/AIDS countries in

Southeast Asia. In 2001, MSF started introducing antiretroviral (ARV)

therapy to AIDS patients for free. This therapy prolongs the patients'

lives and is a long-term treatment.

In 2002, MSF established chronic diseases clinics with the Cambodian

Ministry of Health in various provinces to integrate HIV/AIDS treatment,

alongside hypertension, diabetes, and arthritis which have high

prevalence rate. This aims to reduce facility-related stigma as patients

are able to seek treatment in a multi-purpose clinic in contrast to a

HIV/AIDS specialised treatment centre.

MSF also provided humanitarian aid in times of natural disaster

such as a major flood in 2002 which affected up to 1.47 million people.

MSF introduced a community-based tuberculosis programme in 2004 in

remote villages, where village volunteers are delegated to facilitate

the medication of patients. In partnership with local health authorities

and other NGOs, MSF encouraged decentralized clinics and rendered

localized treatments to more rural areas from 2006.

Since 2007, MSF has extended general health care, counselling, HIV/AIDS

and TB treatment to prisons in Phnom Penh via mobile clinics.

However, poor sanitation and lack of health care still prevails in most

Cambodian prisons as they remain as some of the world's most crowded

prisons.

In 2007, MSF worked with the Cambodian Ministry of Health to

provide psychosocial and technical support in offering pediatric

HIV/AIDS treatment to affected children. MSF also provided medical supplies and staff to help in one of the worst dengue outbreaks in 2007, which had more than 40,000 people hospitalized, killing 407 people, primarily children.

In 2010, Southern and Eastern provinces of Cambodia were hit with

a cholera epidemic and MSF responded by providing medical support that

were adapted for usage in the country.

Cambodia is one of 22 countries listed by WHO as having a high

burden of tuberculosis. WHO estimates that 64% of all Cambodians carry

the tuberculosis mycobacterium. Hence, MSF has since shifted its focus

away from HIV/AIDS to tuberculosis, handing over most HIV-related

programs to local health authorities.

Libya

The

2011 Libyan civil war

has prompted efforts by MSF to set up a hospital and mental health

services to help locals affected by the conflict. The fighting created a

backlog of patients that needed surgery. With parts of the country

slowly returning to livable, MSF has started working with local health

personnel to address the needs. The need for psychological counseling

has increased and MSF has set up mental health services to address the

fears and stress of people living in tents without water and

electricity. Currently MSF is the only International Aid organisation

with actual presence in the country.

Mediterranean Sea

MSF

is providing Maritime Search And Rescue (SAR) services on the

Mediterranean Sea to save the lives of migrants attempting to cross with

unseaworthy boats. The Mission started in 2015 after the EU ended its

major SAR operation

Mare Nostrum severely diminishing much needed SAR capacities in the Mediterranean.

Throughout the mission MSF has operated its own vessels like the

Bourbon Argos (2015–2016), Dignity I (2015–2016) and Prudence

(2016–2017). MSF has also provided medical teams to support other NGOs

and their ships like the

MOAS Phoenix (2015) or the Aquarius with SOS Méditerranée (2017–2018).

In August 2017 MSF decided to suspend the activities of the Prudence

protesting restrictions and threats by the Libyan "Coast Guard".

In December 2018 MSF and SOS Méditerranée were forced to end

operations of the Aquarius, the last remaining vessel supported by MSF.

This came after attacks by EU states that stripped the vessel of its

registration and produced criminal accusations against MSF. Up to then

80,000 people were rescued or assisted since the beginning of the

mission.

Sri Lanka

MSF is involved in Sri Lanka, where a

26 year civil war

ended in 2009 and MSF has adapted its activities there to continue its

mission. For example, it helps with physical therapy for patients with

spinal cord injuries.

It conducts counseling sessions, and has set up an “operating theatre

for reconstructive orthopaedic surgery and supplied specialist surgeons,

anaesthetists and nurses to operate on patients with complicated

war-related injuries.”

Yemen

MSF is involved in trying to help with the humanitarian crisis caused by the

Yemeni Civil War.

The organisation operates eleven hospital and health centres in Yemen

and provides support to another 18 hospitals or health centres.

According to MSF, since October 2015, four of its hospitals and one

ambulance have been destroyed by Saudi-led coalition airstrikes. In August 2016, an airstrike on Abs hospital killed 19 people, including one MSF staff member, and wounded 24.

According to MSF, the GPS coordinates of the hospital were repeatedly

shared with all parties to the conflict, including the Saudi-led

coalition, and its location was well-known.

Field mission structure

Before

a field mission is established in a country, an MSF team visits the

area to determine the nature of the humanitarian emergency, the level of

safety in the area and what type of aid is needed (this is called an

"exploratory mission").

Medical aid is the main objective of most missions, although some missions help in such areas as

water purification and nutrition.

Field mission team

MSF logistician in Nigeria showing plans

A field mission team usually consists of a small number of

coordinators to head each component of a field mission, and a "head of

mission." The head of mission usually has the most experience in

humanitarian situations of the members of the team, and it is his/her

job to deal with the media, national governments and other humanitarian

organizations. The head of mission does not necessarily have a medical

background.

Medical volunteers include physicians, surgeons, nurses, and

various other specialists. In addition to operating the medical and

nutrition components of the field mission, these volunteers are

sometimes in charge of a group of local medical staff and provide

training for them.

Although the medical volunteers almost always receive the most

media attention when the world becomes aware of an MSF field mission,

there are a number of non-medical volunteers who help keep the field

mission functioning. Logisticians are responsible for providing

everything that the medical component of a mission needs, ranging from

security and vehicle maintenance to food and electricity supplies. They

may be engineers and/or

foremen,

but they usually also help with setting up treatment centres and

supervising local staff. Other non-medical staff are water/sanitation

specialists, who are usually experienced engineers in the fields of

water treatment and management and financial/administration/human

resources experts who are placed with field missions.

Medical component

Doctors from MSF and the American CDC put on protective gear before entering an Ebola treatment ward in Liberia, August 2014

Vaccination campaigns are a major part of the medical care provided during MSF missions. Diseases such as

diphtheria,

measles,

meningitis,

tetanus,

pertussis,

yellow fever,

polio, and

cholera, all of which are uncommon in developed countries, may be prevented with

vaccination.

Some of these diseases, such as cholera and measles, spread rapidly in

large populations living in close proximity, such as in a refugee camp,

and people must be immunised by the hundreds or thousands in a short

period of time. For example, in

Beira, Mozambique in 2004, an experimental cholera vaccine was received twice by approximately 50,000 residents in about one month.

An equally important part of the medical care provided during MSF missions is AIDS treatment (with

antiretroviral drugs),

AIDS testing, and education. MSF is the only source of treatment for

many countries in Africa, whose citizens make up the majority of people

with HIV and AIDS worldwide. Because antiretroviral drugs (ARVs) are not readily available, MSF usually provides treatment for

opportunistic infections and educates the public on how to slow transmission of the disease.

In most countries, MSF increases the capabilities of local

hospitals by improving sanitation, providing equipment and drugs, and

training local hospital staff.

When the local staff is overwhelmed, MSF may open new specialised

clinics for treatment of an endemic disease or surgery for victims of

war. International staff start these clinics but MSF strives to increase

the local staff's ability to run the clinics themselves through

training and supervision. In some countries, like Nicaragua, MSF provides public education to increase awareness of reproductive health care and

venereal disease.

Since most of the areas that require field missions have been

affected by a natural disaster, civil war, or endemic disease, the

residents usually require psychological support as well. Although the

presence of an MSF medical team may decrease stress somewhat among

victims, often a team of

psychologists or

psychiatrists work with victims of depression,

domestic violence and

substance abuse. The doctors may also train local mental health staff.

Nutrition

Often in situations where an MSF mission is set up, there is moderate or severe

malnutrition

as a result of war, drought, or government economic mismanagement.

Intentional starvation is also sometimes used during a war as a weapon,

and MSF, in addition to providing food, brings awareness to the

situation and insists on foreign government intervention. Infectious

diseases and

diarrhoea,

both of which cause weight loss and weakening of a person's body

(especially in children), must be treated with medication and proper

nutrition to prevent further infections and weight loss. A combination

of the above situations, as when a civil war is fought during times of

drought and infectious disease outbreaks, can create famine.

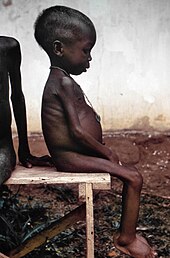

An MSF health worker examines a malnourished child in Ethiopia, July 2011

In emergency situations where there is a lack of nutritious food, but not to the level of a true famine,

protein-energy malnutrition is most common among young children.

Marasmus,

a form of calorie deficiency, is the most common form of childhood

malnutrition and is characterised by severe wasting and often fatal

weakening of the immune system.

Kwashiorkor, a form of calorie and protein deficiency, is a more serious type of malnutrition in young children, and can negatively affect

physical and

mental development. Both types of malnutrition can make opportunistic infections fatal. In these situations, MSF sets up

Therapeutic Feeding Centres for monitoring the children and any other malnourished individuals.

A Therapeutic Feeding Centre (or Therapeutic Feeding Programme)

is designed to treat severe malnutrition through the gradual

introduction of a special diet intended to promote weight gain after the

individual has been treated for other health problems. The treatment

programme is split between two phases:

- Phase 1 lasts for 24 hours and involves basic health care and

several small meals of low energy/protein food spaced over the day.

- Phase 2 involves monitoring of the patient and several small meals

of high energy/protein food spaced over each day until the individual's

weight approaches normal.

MSF uses foods designed specifically for treatment of severe malnutrition. During phase 1, a type of therapeutic milk called

F-75

is fed to patients. F-75 is a relatively low energy, low fat/protein

milk powder that must be mixed with water and given to patients to

prepare their bodies for phase 2. During phase 2, therapeutic milk called

F-100,

which is higher in energy/fat/protein content than F-75, is given to

patients, usually along with a peanut butter mixture called

Plumpy'nut. F-100 and Plumpy'nut are designed to quickly provide large amounts of nutrients so that patients can be treated efficiently. Other special food fed to populations in danger of starvation includes

enriched flour and

porridge, as well as a high protein biscuit called

BP5.

BP5 is a popular food for treating populations because it can be

distributed easily and sent home with individuals, or it can be crushed

and mixed with therapeutic milk for specific treatments.

Water and sanitation

Clean water is essential for

hygiene,

for consumption and for feeding programmes (for mixing with powdered

therapeutic milk or porridge), as well as for preventing the spread of

water-borne disease.

As such, MSF water engineers and volunteers must create a source of

clean water. This is usually achieved by modifying an existing

water well,

by digging a new well and/or starting a water treatment project to

obtain clean water for a population. Water treatment in these situations

may consist of storage sedimentation,

filtration and/or

chlorination depending on available resources.

Sanitation is an essential part of field missions, and it may include education of local medical staff in proper

sterilisation techniques,

sewage treatment projects, proper

waste disposal,

and education of the population in personal hygiene. Proper wastewater

treatment and water sanitation are the best way to prevent the spread of

serious water-borne diseases, such as cholera. Simple wastewater treatment systems can be set up by volunteers to protect drinking water from contamination. Garbage disposal could include pits for normal waste and incineration for

medical waste.

However, the most important subject in sanitation is the education of

the local population, so that proper waste and water treatment can

continue once MSF has left the area.

Statistics

In

order to accurately report the conditions of a humanitarian emergency

to the rest of the world and to governing bodies, data on a number of

factors are collected during each field mission. The rate of

malnutrition in children is used to determine the malnutrition rate in

the population, and then to determine the need for feeding centres. Various types of

mortality rates

are used to report the seriousness of a humanitarian emergency, and a

common method used to measure mortality in a population is to have staff

constantly monitoring the number of burials at cemeteries.

By compiling data on the frequency of diseases in hospitals, MSF can

track the occurrence and location of epidemic increases (or "seasons")

and stockpile vaccines and other drugs. For example, the "Meningitis

Belt" (sub-Saharan Africa, which sees the most cases of meningitis in

the world) has been "mapped" and the meningitis season occurs between

December and June. Shifts in the location of the Belt and the timing of

the season can be predicted using cumulative data over many years.

In addition to epidemiological surveys, MSF also uses population

surveys to determine the rates of violence in various regions. By estimating the scopes of

massacres, and determining the rate of kidnappings, rapes, and killings, psychosocial programmes can be implemented to lower the

suicide rate and increase the sense of security in a population.

Large-scale forced migrations,

excessive civilian casualties and massacres can be quantified using

surveys, and MSF can use the results to put pressure on governments to

provide help, or even expose genocide. MSF conducted the first comprehensive mortality survey in

Darfur in 2004.

However, there may be ethical problems in collecting these statistics.

Campaign for Access to Essential Medicines

The Campaign for Access to Essential Medicines was initiated in 1999 to increase access to

essential medicines

in developing countries. "Essential medicines" are those drugs that are

needed in sufficient supply to treat a disease common to a population.

However, most diseases common to populations in developing countries

are no longer common to populations in developed countries; therefore,

pharmaceutical companies

find that producing these drugs is no longer profitable and may raise

the price per treatment, decrease development of the drug (and new

treatments) or even stop production of the drug. MSF often lacks

effective drugs during field missions, and started the campaign to put

pressure on governments and pharmaceutical companies to increase funding

for essential medicines.

In recent years, the organization has tried to use its influence to urge the drug maker

Novartis to drop its case against India's patent law that prevents Novartis from patenting its drugs in

India. A few years earlier, Novartis also sued

South Africa to prevent it from importing cheaper

AIDS

drugs. Dr. Tido von Schoen-Angerer, director of DWB's Campaign for

Access to Essential Medicines, says, "Just like five years ago,

Novartis, with its legal actions, is trying to stand in the way of

people's right to access the medicines they need."

On 1 April 2013, it was announced that the Indian court

invalidated Novartis's patent on Gleevec. This decision makes the drug

available via generics on the Indian market at a considerably lower

price.

Dangers faced by volunteers

Aside

from injuries and death associated with stray bullets, mines and

epidemic disease, MSF volunteers are sometimes attacked or kidnapped for

political reasons. In some countries afflicted by civil war,

humanitarian-aid organizations are viewed as helping the enemy. If an

aid mission is perceived to be exclusively set up for victims on one

side of the conflict, it may come under attack for that reason. However,

the

War on Terrorism

has generated attitudes among some groups in US-occupied countries that

non-governmental aid organizations such as MSF are allied with or even

work for the

Coalition forces.

Since the United States has labelled its operations "humanitarian

actions," independent aid organizations have been forced to defend their

positions, or even evacuate their teams.

Insecurity in cities in Afghanistan and Iraq rose significantly

following United States operations, and MSF has declared that providing

aid in these countries was too dangerous. The organization was forced to evacuate its teams from Afghanistan on 28 July 2004, after five volunteers (Afghans Fasil Ahmad and Besmillah, Belgian Hélène de Beir, Norwegian

Egil Tynæs, and Dutchman Willem Kwint) were killed on 2 June in an ambush by unidentified militia near

Khair Khāna in

Badghis Province. In June 2007, Elsa Serfass, a volunteer with MSF-France, was killed

in the Central African Republic and in January 2008, two expatriate

staff (Damien Lehalle and Victor Okumu) and a national staff member

(Mohammed Bidhaan Ali) were killed in an organized attack in Somalia resulting in the closing of the project.

Arrests and abductions in politically unstable regions can also

occur for volunteers, and in some cases, MSF field missions can be

expelled entirely from a country.

Arjan Erkel, Head of Mission in

Dagestan in the

North Caucasus,

was kidnapped and held hostage in an unknown location by unknown

abductors from 12 August 2002 until 11 April 2004. Paul Foreman, head of

MSF-Holland, was arrested in Sudan in May 2005 for refusing to divulge

documents used in compiling a report on rapes carried out by the

pro-government

Janjaweed militias.

Foreman cited the privacy of the women involved, and MSF alleged that

the Sudanese government had arrested him because it disliked the bad

publicity generated by the report.

On 14 August 2013, MSF announced that it was closing all of its programmes in Somalia due to attacks on its staff by

Al-Shabaab militants and perceived indifference or

inurement to this by the governmental authorities and wider society.

On 28 November 2015, an MSF-supported hospital was barrel-bombed

by a Syrian Air Force helicopter, killing seven and wounding forty-seven

people near Homs, Syria.

On 10 January 2016, an MSF-supported hospital in Sa'dah was bombed by the

Saudi Arabia-led military coalition, killing six people.

On 15 February 2016, two MSF-supported hospitals in

Idlib District and

Aleppo, Syria were bombed, killing at least 20 and injuring dozens of patients and medical personnel. Both Russia and the United States denied responsibility and being in the area at the time.

On 28 April 2016, an MSF hospital in Aleppo was bombed, killing 50, including six staff and patients.

Documentary

Living in Emergency is an award-winning documentary film by

Mark N. Hopkins

that tells the story of four MSF volunteer doctors confronting the

challenges of medical work in war-torn areas of Liberia and Congo. It

premiered at the 2008

Venice Film Festival and was theatrically released in the United States in 2010.

1999 Nobel Peace Prize

The then president of MSF,

James Orbinski,

gave the Nobel Peace Prize speech on behalf of the organization. In

the opening, he discusses the conditions of the victims of the Rwandan

Genocide and focuses on one of his woman patients:

There were hundreds of women,

children and men brought to the hospital that day, so many that we had

to lay them out on the street and even operate on some of them there.

The gutters around the hospital ran red with blood. The woman had not

just been attacked with a machete, but her entire body rationally and

systematically mutilated. Her ears had been cut off. And her face had

been so carefully disfigured that a pattern was obvious in the slashes.

She was one among many—living an inhuman and simply indescribable

suffering. We could do little more for her at the moment than stop the

bleeding with a few necessary sutures. We were completely overwhelmed,

and she knew that there were so many others. She said to me in the

clearest voice I have ever heard, 'Allez, allez…ummera, ummerasha'—'Go,

go…my friend, find and let live your courage.'

— James Orbinski, Nobel acceptance speech for MSF

Orbinski affirmed the organization's commitment to publicizing the issues MSF encountered, stating

Silence has long been confused with

neutrality, and has been presented as a necessary condition for

humanitarian action. From its beginning, MSF was created in opposition

to this assumption. We are not sure that words can always save lives,

but we know that silence can certainly kill.

— James Orbinski

Lasker Prize

Namesakes