Hotel union workers strike with the slogan "One job should be enough" | |

| National organization(s) | AFL-CIO, CtW, IWW |

|---|---|

| Regulatory authority | United States Department of Labor National Labor Relations Board |

| Primary legislation | National Labor Relations Act Taft-Hartley Act |

| Total union membership | 14.6 million |

| Percentage of workforce; | ▪ Total: 10.3% ▪ Public sector:

33.6% |

| Standard Occupational Classification | ▪ Management, professional:

11.9% |

| International Labour Organization | |

| United States is a member of the ILO | |

| Convention ratification | |

| Freedom of Association | Not ratified |

| Right to Organise | Not ratified |

Labor unions in the United States are organizations that represent workers in many industries recognized under US labor law since the 1935 enactment of the National Labor Relations Act. Their activity today centers on collective bargaining over wages, benefits, and working conditions for their membership, and on representing their members in disputes with management over violations of contract provisions. Larger trade unions also typically engage in lobbying activities and electioneering at the state and federal level.

Most unions in the United States are aligned with one of two larger umbrella organizations: the AFL-CIO created in 1955, and the Change to Win Federation which split from the AFL-CIO in 2005. Both advocate policies and legislation on behalf of workers in the United States and Canada, and take an active role in politics. The AFL-CIO is especially concerned with global trade issues.

The percentage of workers belonging to a union (or total labor union "density") varies by country. In 2019 it was 10.3% in the United States, compared to 20.1% in 1983. There were 14.6 million members in the U.S., down from 17.7 million in 1983. Union membership in the private sector has fallen to 6.2%, one fifth that of public sector workers, at 33.6%. Over half of all union members in the U.S. lived in just seven states (California, New York, Illinois, Pennsylvania, New Jersey, Ohio, and Washington), though these states accounted for only about one-third of the workforce. From a global perspective, in 2016 the US had the fifth lowest trade union density of the 36 OECD member nations.

In the 21st century, the most prominent unions are among public sector employees such as city employees, government workers, teachers and police. Members of unions are disproportionately older, male, and residents of the Northeast, the Midwest, and California. Union workers average 10-30% higher pay than non-union in the United States after controlling for individual, job, and labor market characteristics.

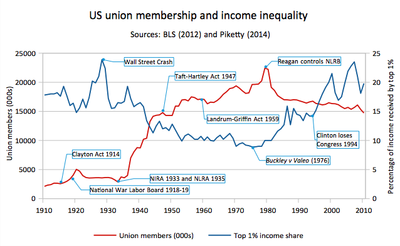

Although much smaller compared to their peak membership in the 1950s, American unions remain a political factor, both through mobilization of their own memberships and through coalitions with like-minded activist organizations around issues such as immigrant rights, trade policy, health care, and living wage campaigns. Of special concern are efforts by cities and states to reduce the pension obligations owed to unionized workers who retire in the future. Republicans elected with Tea Party support in 2010, most notably former Governor Scott Walker of Wisconsin, have launched major efforts against public sector unions due in part to state government pension obligations (even though Wisconsin's state pension is 100% funded as of 2015) along with the allegation that the unions are too powerful. The academic literature shows substantial evidence that labor unions reduce economic inequality. Research indicates that rising income inequality in the United States is partially attributable to the decline of the labor movement and union membership.

History

Unions began forming in the mid-19th century in response to the social and economic impact of the Industrial Revolution. National labor unions began to form in the post-Civil War Era. The Knights of Labor emerged as a major force in the late 1880s, but it collapsed because of poor organization, lack of effective leadership, disagreement over goals, and strong opposition from employers and government forces.

The American Federation of Labor, founded in 1886 and led by Samuel Gompers until his death in 1924, proved much more durable. It arose as a loose coalition of various local unions. It helped coordinate and support strikes and eventually became a major player in national politics, usually on the side of the Democrats.

American labor unions benefited greatly from the New Deal policies of Franklin Delano Roosevelt in the 1930s. The Wagner Act, in particular, legally protected the right of unions to organize. Unions from this point developed increasingly closer ties to the Democratic Party, and are considered a backbone element of the New Deal Coalition.

Post-WWII

Pro-business conservatives gained control of Congress in 1946, and in 1947 passed the Taft-Hartley Act, drafted by Senator Robert A. Taft. President Truman vetoed it but the Conservative coalition overrode the veto. The veto override had considerable Democratic support, including 106 out of 177 Democrats in the House, and 20 out of 42 Democrats in the Senate. The law, which is still in effect, banned union contributions to political candidates, restricted the power of unions to call strikes that "threatened national security," and forced the expulsion of Communist union leaders (the Supreme Court found the anti-communist provision to be unconstitutional, and it is no longer in force). The unions campaigned vigorously for years to repeal the law but failed. During the late 1950s, the Landrum Griffin Act of 1959 passed in the wake of Congressional investigations of corruption and undemocratic internal politics in the Teamsters and other unions.

In 1955, the two largest labor organizations, the AFL and CIO, merged, ending a division of over 20 years. AFL President George Meany became President of the new AFL-CIO, and AFL Secretary-Treasurer William Schnitzler became AFL-CIO Secretary-Treasurer. The draft constitution was primarily written by AFL Vice President Matthew Woll and CIO General Counsel Arthur Goldberg, while the joint policy statements were written by Woll, CIO Secretary-Treasurer James Carey, CIO vice presidents David McDonald and Joseph Curran, Brotherhood of Railway Clerks President George Harrison, and Illinois AFL-CIO President Reuben Soderstrom.

The percentage of workers belonging to a union (or "density") in the United States peaked in 1954 at almost 35% (citation needed) and the total number of union members peaked in 1979 at an estimated 21.0 million. Membership has declined since, with private sector union membership beginning a steady decline that continues into the 2010s, but the membership of public sector unions grew steadily.

After 1960 public sector unions grew rapidly and secured good wages and high pensions for their members. While manufacturing and farming steadily declined, state- and local-government employment quadrupled from 4 million workers in 1950 to 12 million in 1976 and 16.6 million in 2009. Adding in the 3.7 million federal civilian employees, in 2010 8.4 million government workers were represented by unions, including 31% of federal workers, 35% of state workers and 46% of local workers.

By the 1970s, a rapidly increasing flow of imports (such as automobiles, steel and electronics from Germany and Japan, and clothing and shoes from Asia) undercut American producers. By the 1980s there was a large-scale shift in employment with fewer workers in high-wage sectors and more in the low-wage sectors. Many companies closed or moved factories to Southern states (where unions were weak), countered the threat of a strike by threatening to close or move a plant, or moved their factories offshore to low-wage countries. The number of major strikes and lockouts fell by 97% from 381 in 1970 to 187 in 1980 to only 11 in 2010. On the political front, the shrinking unions lost influence in the Democratic Party, and pro-Union liberal Republicans faded away. Union membership among workers in private industry shrank dramatically, though after 1970 there was growth in employees unions of federal, state and local governments. The intellectual mood in the 1970s and 1980s favored deregulation and free competition. Numerous industries were deregulated, including airlines, trucking, railroads and telephones, over the objections of the unions involved. The climax came when President Ronald Reagan—a former union president—broke the Professional Air Traffic Controllers Organization (PATCO) strike in 1981, dealing a major blow to unions.

Republicans began to push through legislative blueprints to curb the power of public employee unions as well as eliminate business regulations.

Labor unions today

Today most labor unions (or trade unions) in the United States are members of one of two larger umbrella organizations: the American Federation of Labor–Congress of Industrial Organizations (AFL-CIO) or the Change to Win Federation, which split from the AFL-CIO in 2005-2006. Both organizations advocate policies and legislation favorable to workers in the United States and Canada, and take an active role in politics favoring the Democratic party but not exclusively so. The AFL-CIO is especially concerned with global trade and economic issues.

Private sector unions are regulated by the National Labor Relations Act (NLRA), passed in 1935 and amended since then. The law is overseen by the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB), an independent federal agency. Public sector unions are regulated partly by federal and partly by state laws. In general they have shown robust growth rates, because wages and working conditions are set through negotiations with elected local and state officials.

To join a traditional labor union, workers must either be given voluntary recognition from their employer or have a majority of workers in a bargaining unit vote for union representation. In either case, the government must then certify the newly formed union. Other forms of unionism include minority unionism, solidarity unionism, and the practices of organizations such as the Industrial Workers of the World, which do not always follow traditional organizational models.

Public sector worker unions are governed by labor laws and labor boards in each of the 50 states. Northern states typically model their laws and boards after the NLRA and the NLRB. In other states, public workers have no right to establish a union as a legal entity. (About 40% of public employees in the USA do not have the right to organize a legally established union.)

A review conducted by the federal government on pay scale shows that employees in a labor union earn up to 33% more income than their nonunion counterparts, as well as having more job security, and safer and higher-quality work conditions. The median weekly income for union workers was $973 in 2014, compared with $763 for nonunion workers.

Labor negotiations

Once the union won the support of a majority of the bargaining unit and is certified in a workplace, it has the sole authority to negotiate the conditions of employment. Under the NLRA, employees can also, if there is no majority support, form a minority union which represents the rights of only those members who choose to join. Businesses, however, do not have to recognize the minority union as a collective bargaining agent for its members, and therefore the minority union's power is limited. This minority model was once widely used, but was discarded when unions began to consistently win majority support. Unions are beginning to revisit the members-only model of unionism, because of new changes to labor law, which unions view as curbing workers' ability to organize.

The employer and the union write the terms and conditions of employment in a legally binding contract. When disputes arise over the contract, most contracts call for the parties to resolve their differences through a grievance process to see if the dispute can be mutually resolved. If the union and the employer still cannot settle the matter, either party can choose to send the dispute to arbitration, where the case is argued before a neutral third party.

Right-to-work statutes forbid unions from negotiating union shops and agency shops. Thus, while unions do exist in "right-to-work" states, they are typically weaker.

Members of labor unions enjoy "Weingarten Rights." If management questions the union member on a matter that may lead to discipline or other changes in working conditions, union members can request representation by a union representative. Weingarten Rights are named for the first Supreme Court decision to recognize those rights.

The NLRA goes farther in protecting the right of workers to organize unions. It protects the right of workers to engage in any "concerted activity" for mutual aid or protection. Thus, no union connection is needed. Concerted activity "in its inception involves only a speaker and a listener, for such activity is an indispensable preliminary step to employee self-organization."

Unions are currently advocating new federal legislation, the Employee Free Choice Act (EFCA), that would allow workers to elect union representation by simply signing a support card (card check). The current process established by federal law requires at least 30% of employees to sign cards for the union, then wait 45 to 90 days for a federal official to conduct a secret ballot election in which a simple majority of the employees must vote for the union in order to obligate the employer to bargain.

Unions report that, under the present system, many employers use the 45- to 90-day period to conduct anti-union campaigns. Some opponents of this legislation fear that removing secret balloting from the process will lead to the intimidation and coercion of workers on behalf of the unions. During the 2008 elections, the Employee Free Choice Act had widespread support of many legislators in the House and Senate, and of the President. Since then, support for the "card check" provisions of the EFCA subsided substantially.

Membership

Union membership had been declining in the US since 1954, and since 1967, as union membership rates decreased, middle class incomes shrank correspondingly. In 2007, the labor department reported the first increase in union memberships in 25 years and the largest increase since 1979. Most of the recent gains in union membership have been in the service sector while the number of unionized employees in the manufacturing sector has declined. Most of the gains in the service sector have come in West Coast states like California where union membership is now at 16.7% compared with a national average of about 12.1%. Historically, the rapid growth of public employee unions since the 1960s has served to mask an even more dramatic decline in private-sector union membership.

At the apex of union density in the 1940s, only about 9.8% of public employees were represented by unions, while 33.9% of private, non-agricultural workers had such representation. In this decade, those proportions have essentially reversed, with 36% of public workers being represented by unions while private sector union density had plummeted to around 7%. The US Bureau of Labor Statistics most recent survey indicates that union membership in the US has risen to 12.4% of all workers, from 12.1% in 2007. For a short period, private sector union membership rebounded, increasing from 7.5% in 2007 to 7.6% in 2008. However, that trend has since reversed. In 2013 there were 14.5 million members in the U.S., compared with 17.7 million in 1983. In 2013, the percentage of workers belonging to a union was 11.3%, compared to 20.1% in 1983. The rate for the private sector was 6.4%, and for the public sector 35.3%.

In the ten years 2005 through 2014, the National Labor Relations Board recorded 18,577 labor union representation elections; in 11,086 of these elections (60 percent), the majority of workers voted for union representation. Most of the elections (15,517) were triggered by employee petitions for representation, of which unions won 9,933. Less common were elections caused by employee petitions for decertification (2792, of which unions won 1070), and employer-filed petitions for either representation or decertification (268, of which unions won 85).

Labor education programs

In the US, labor education programs such as the Harvard Trade Union Program created in 1942 by Harvard University professor John Thomas Dunlop sought to educate union members to deal with important contemporary workplace and labor law issues of the day. The Harvard Trade Union Program is currently part of a broader initiative at Harvard Law School called the Labor and Worklife Program that deals with a wide variety of labor and employment issues from union pension investment funds to the effects of nanotechnology on labor markets and the workplace.

Cornell University is known to be one of the leading centers for labor education in the world, establishing the Cornell University School of Industrial and Labor Relations in 1945. The school's mission is to prepare leaders, inform national and international employment and labor policy, and improve working lives through undergraduate and graduate education. The school publishes the Industrial and Labor Relations Review and had Frances Perkins on its faculty. The school has six academic departments: Economics, Human Resource Management, International and Comparative Labor, Labor Relations, Organizational Behavior, and Social Statistics. Classes include "Politics of the Global North" and "Economic Analysis of the University."

Jurisdiction

Labor unions use the term jurisdiction to refer to their claims to represent workers who perform a certain type of work and the right of their members to perform such work. For example, the work of unloading containerized cargo at United States ports, which the International Longshoremen's Association, the International Longshore and Warehouse Union and the International Brotherhood of Teamsters have claimed rightfully should be assigned to workers they represent. A jurisdictional strike is a concerted refusal to work undertaken by a union to assert its members' right to such job assignments and to protest the assignment of disputed work to members of another union or to unorganized workers. Jurisdictional strikes occur most frequently in the United States in the construction industry.

Unions also use jurisdiction to refer to the geographical boundaries of their operations, as in those cases in which a national or international union allocates the right to represent workers among different local unions based on the place of those workers' employment, either along geographical lines or by adopting the boundaries between political jurisdictions.

Public opinion

Although not as overwhelmingly supportive as it was from the 1930s through the early 1960s, a clear majority of the American public approves of labor unions. The Gallup organization has tracked public opinion of unions since 1936, when it found that 72 percent approved of unions. The overwhelming approval declined in the late 1960s, but - except for one poll in 2009 in which the unions received a favorable rating by only 48 percent of those interviewed, majorities have always supported labor unions. A Gallup Poll released August 2018 showed 62% of respondents approving unions, the highest level in over a decade. Disapproval of unions was expressed by 32%.

On the question of whether or not unions should have more influence or less influence, Gallup has found the public consistently split since Gallup first posed the question in 2000, with no majority favoring either more influence or less influence. In August 2018, 39 percent wanted unions to have more influence, 29 percent less influence, with 26 percent wanting the influence of labor unions to remain about the same.

A Pew Research Center poll from 2009-2010 found a drop in labor union support in the midst of The Great Recession sitting at 41% favorable and 40% unfavorable. In 2018, union support rose to 55% favorable with just 33% unfavorable Despite this union membership had continued to fall.

Possible causes of drop in membership

Although most industrialized countries have seen a drop in unionization rates, the drop in union density (the unionized proportion of the working population) has been more significant in the United States than elsewhere.

Global trends

The US Bureau of Labor Statistics surveyed the histories of union membership rates in industrialized countries from 1970 to 2003, and found that of 20 advanced economies which had union density statistics going back to 1970, 16 of them had experienced drops in union density from 1970 to 2003. Over the same period during which union density in the US declined from 23.5 percent to 12.4 percent, some counties saw even steeper drops. Australian unionization fell from 50.2 percent in 1970 to 22.9 percent in 2003, in New Zealand it dropped from 55.2 percent to 22.1 percent, and in Austria union participation fell from 62.8 percent down to 35.4 percent. All the English-speaking countries studied saw union membership decline to some degree. In the United Kingdom, union participation fell from 44.8 percent in 1970 to 29.3 percent in 2003. In Ireland the decline was from 53.7 percent down to 35.3 percent. Canada had one of the smallest declines over the period, going from 31.6 percent in 1970 to 28.4 percent in 2003. Most of the countries studied started in 1970 with higher participation rates than the US, but France, which in 1970 had a union participation rate of 21.7 percent, by 2003 had fallen to 8.3 percent. The remaining four countries which had gained in union density were Finland, Sweden, Denmark, and Belgium.

Popularity

Public approval of unions climbed during the 1980s much as it did in other industrialized nations, but declined to below 50% for the first time in 2009 during the Great Recession. It is not clear if this is a long term trend or a function of a high unemployment rate which historically correlates with lower public approval of labor unions.

One explanation for loss of public support is simply the lack of union power or critical mass. No longer do a sizable percentage of American workers belong to unions, or have family members who do. Unions no longer carry the "threat effect": the power of unions to raise wages of non-union shops by virtue of the threat of unions to organize those shops.

Polls of public opinion and labor unions

A New York Times/CBS Poll found that 60% of Americans opposed restricting collective bargaining while 33% were for it. The poll also found that 56% of Americans opposed reducing pay of public employees compared to the 37% who approved. The details of the poll also stated that 26% of those surveyed, thought pay and benefits for public employees were too high, 25% thought too low, and 36% thought about right. Mark Tapscott of the Washington Examiner criticized the poll, accusing it of over-sampling union and public employee households.

A Gallup poll released on March 9, 2011, showed that Americans were more likely to support limiting the collective bargaining powers of state employee unions to balance a state's budget (49%) than disapprove of such a measure (45%), while 6% had no opinion. 66% of Republicans approved of such a measure as did 51% of independents. Only 31% of Democrats approved.

A Gallup poll released on March 11, 2011, showed that nationwide, Americans were more likely to give unions a negative word or phrase when describing them (38%) than a positive word or phrase (34%). 17% were neutral and 12% didn't know. Republicans were much more likely to say a negative term (58%) than Democrats (19%). Democrats were much more likely to say a positive term (49%) than Republicans (18%).

A nationwide Gallup poll (margin of error ±4%) released on April 1, 2011, showed the following;

- When asked if they supported the labor unions or the governors in state disputes; 48% said they supported the unions, 39% said the governors, 4% said neither, and 9% had no opinion.

- Women supported the governors much less than men. 45% of men said they supported the governors, while 46% said they supported the unions. This compares to only 33% of women who said they supported the governors and 50% who said they supported the unions.

- All areas of the US (East, Midwest, South, West) were more likely to support unions than the governors. The largest gap being in the East with 35% supporting the governors and 52% supporting the unions, and the smallest gap being in the West with 41% supporting the governors and 44% the unions.

- 18- to 34-year-olds were much more likely to support unions than those over 34 years of age. Only 27% of 18- to 34-year-olds supported the governors, while 61% supported the unions. Americans ages 35 to 54 slightly supported the unions more than governors, with 40% supporting the governors and 43% the unions. Americans 55 and older were tied when asked, with 45% supporting the governors and 45% the unions.

- Republicans were much more likely to support the governors when asked with 65% supporting the governors and 25% the unions. Independents slightly supported unions more, with 40% supporting the governors and 45% the unions. Democrats were overwhelmingly in support of the unions. 70% of Democrats supported the unions, while only 19% supported the governors.

- Those who said they were following the situation not too closely or not at all supported the unions over governors, with a 14–point (45% to 31%) margin. Those who said they were following the situation somewhat closely supported the unions over governors by a 52–41 margin. Those who said that they were following the situation very closely were only slightly more likely to support the unions over the governors, with a 49-48 margin.

A nationwide Gallup poll released on August 31, 2011, revealed the following:

- 52% of Americans approved of labor unions, unchanged from 2010.

- 78% of Democrats approved of labor unions, up from 71% in 2010.

- 52% of Independents approved of labor unions, up from 49% in 2010.

- 26% of Republicans approved of labor unions, down from 34% in 2010.

A nationwide Gallup poll released on September 1, 2011, revealed the following:

- 55% of Americans believed that labor unions will become weaker in the United States as time goes by, an all-time high. This compared to 22% who said their power would stay the same, and 20% who said they would get stronger.

- The majority of Republicans and Independents believed labor unions would further weaken by a 58% and 57% percentage margin respectively. A plurality of Democrats believed the same, at 46%.

- 42% of Americans want labor unions to have less influence, tied for the all-time high set in 2009. 30% wanted more influence and 25% wanted the same amount of influence.

- The majority of Republicans wanted labor unions to have less influence, at 69%.

- A plurality of Independents wanted labor unions to have less influence, at 40%.

- A plurality of Democrats wanted labor unions to have more influence, at 45%.

- The majority of Americans believed labor unions mostly helped members of unions by a 68 to 28 margin.

- A plurality of Americans believed labor unions mostly helped the companies where workers are unionized by a 48-44 margin.

- A plurality of Americans believed labor unions mostly helped state and local governments by a 47-45 margin.

- A plurality of Americans believed labor unions mostly hurt the US economy in general by a 49-45 margin.

- The majority of Americans believed labor unions mostly hurt workers who are not members of unions by a 56-34 margin.

Institutional environments

A broad range of forces have been identified as potential contributors to the drop in union density across countries. Sano and Williamson outline quantitative studies that assess the relevance of these factors across countries. The first relevant set of factors relate to the receptiveness of unions' institutional environments. For example, the presence of a Ghent system (where unions are responsible for the distribution of unemployment insurance) and of centralized collective bargaining (organized at a national or industry level as opposed to local or firm level) have both been shown to give unions more bargaining power and to correlate positively to higher rates of union density.

Unions have enjoyed higher rates of success in locations where they have greater access to the workplace as an organizing space (as determined both by law and by employer acceptance), and where they benefit from a corporatist relationship to the state and are thus allowed to participate more directly in the official governance structure. Moreover, the fluctuations of business cycles, particularly the rise and fall of unemployment rates and inflation, are also closely linked to changes in union density.

Labor legislation

Labor lawyer Thomas Geoghegan attributes the drop to the long-term effects of the 1947 Taft-Hartley Act, which slowed and then halted labor's growth and then, over many decades, enabled management to roll back labor's previous gains.

First, it ended organizing on the grand, 1930s scale. It outlawed mass picketing, secondary strikes of neutral employers, sit downs: in short, everything [Congress of Industrial Organizations founder John L.] Lewis did in the 1930s.

The second effect of Taft-Hartley was subtler and slower-working. It was to hold up any new organizing at all, even on a quiet, low-key scale. For example, Taft-Hartley ended "card checks." … Taft-Hartley required hearings, campaign periods, secret-ballot elections, and sometimes more hearings, before a union could be officially recognized.

It also allowed and even encouraged employers to threaten workers who want to organize. Employers could hold "captive meetings," bring workers into the office and chew them out for thinking about the Union.

And Taft-Hartley led to the "union-busting" that started in the late 1960s and continues today. It started when a new "profession" of labor consultants began to convince employers that they could violate the [pro-labor 1935] Wagner Act, fire workers at will, fire them deliberately for exercising their legal rights, and nothing would happen. The Wagner Act had never had any real sanctions.

[…]

So why hadn't employers been violating the Wagner Act all along? Well, at first, in the 1930s and 1940s, they tried, and they got riots in the streets: mass picketing, secondary strikes, etc. But after Taft-Hartley, unions couldn't retaliate like this, or they would end up with penalty fines and jail sentences.

In general, scholars debate the influence of politics in determining union strength in the US and other countries. One argument is that political parties play an expected role in determining union strength, with left-wing governments generally promoting greater union density, while others contest this finding by pointing out important counterexamples and explaining the reverse causality inherent in this relationship.

Economic globalization

More recently, as unions have become increasingly concerned with the impacts of market integration on their well-being, scholars have begun to assess whether popular concerns about a global "race to the bottom" are reflected in cross-country comparisons of union strength. These scholars use foreign direct investment (FDI) and the size of a country's international trade as a percentage of its GDP to assess a country's relative degree of market integration. These researchers typically find that globalization does affect union density, but is dependent on other factors, such as unions' access to the workplace and the centralization of bargaining.

Sano and Williamson argue that globalization's impact is conditional upon a country's labor history. In the United States in particular, which has traditionally had relatively low levels of union density, globalization did not appear to significantly affect union density.

Employer strategies

Studies focusing more narrowly on the U.S. labor movement corroborate the comparative findings about the importance of structural factors, but tend to emphasize the effects of changing labor markets due to globalization to a greater extent. Bronfenbrenner notes that changes in the economy, such as increased global competition, capital flight, and the transitions from a manufacturing to a service economy and to a greater reliance on transitory and contingent workers, accounts for only a third of the decline in union density.

Bronfenbrenner claims that the federal government in the 1980s was largely responsible for giving employers the perception that they could engage in aggressive strategies to repress the formation of unions. Richard Freeman also points to the role of repressive employer strategies in reducing unionization, and highlights the way in which a state ideology of anti-unionism tacitly accepted these strategies

Goldfield writes that the overall effects of globalization on unionization in the particular case of the United States may be understated in econometric studies on the subject. He writes that the threat of production shifts reduces unions' bargaining power even if it does not eliminate them, and also claims that most of the effects of globalization on labor's strength are indirect. They are most present in change towards a neoliberal political context that has promoted the deregulation and privatization of some industries and accepted increased employer flexibility in labor markets.

Union responses to globalization

Regardless of the actual impact of market integration on union density or on workers themselves, organized labor has been engaged in a variety of strategies to limit the agenda of globalization and to promote labor regulations in an international context. The most prominent example of this has been the opposition of labor groups to free trade initiatives such as the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) and the Dominican Republic-Central American Free Trade Agreement (DR-CAFTA). In both cases, unions expressed strong opposition to the agreements, but to some extent pushed for the incorporation of basic labor standards in the agreement if one were to pass.

However, Mayer has written that it was precisely unions' opposition to NAFTA overall that jeopardized organized labor's ability to influence the debate on labor standards in a significant way. During Clinton's presidential campaign, labor unions wanted NAFTA to include a side deal to provide for a kind of international social charter, a set of standards that would be enforceable both in domestic courts and through international institutions. Mickey Kantor, then U.S. trade representative, had strong ties to organized labor and believed that he could get unions to come along with the agreement, particularly if they were given a strong voice in the negotiation process.

When it became clear that Mexico would not stand for this kind of an agreement, some critics from the labor movement would not settle for any viable alternatives. In response, part of the labor movement wanted to declare their open opposition to the agreement, and to push for NAFTA's rejection in Congress. Ultimately, the ambivalence of labor groups led those within the Administration who supported NAFTA to believe that strengthening NAFTA's labor side agreement too much would cost more votes among Republicans than it would garner among Democrats, and would make it harder for the United States to elicit support from Mexico.

Graubart writes that, despite unions' open disappointment with the outcome of this labor-side negotiation, labor activists, including the AFL-CIO have used the side agreement's citizen petition process to highlight ongoing political campaigns and struggles in their home countries. He claims that despite the relative weakness of the legal provisions themselves, the side-agreement has served a legitimizing functioning, giving certain social struggles a new kind of standing.

Transnational labor regulation

Unions have recently been engaged in a developing field of transnational labor regulation embodied in corporate codes of conduct. However, O'Brien cautions that unions have been only peripherally involved in this process, and remain ambivalent about its potential effects. They worry that these codes could have legitimizing effects on companies that do not actually live up to good practices, and that companies could use codes to excuse or distract attention from the repression of unions.

Braun and Gearhart note that although unions do participate in the structure of a number of these agreements, their original interest in codes of conduct differed from the interests of human rights and other non-governmental activists. Unions believed that codes of conduct would be important first steps in creating written principles that a company would be compelled to comply with in later organizing contracts, but did not foresee the establishment of monitoring systems such as the Fair Labor Association. These authors point out that are motivated by power, want to gain insider status politically and are accountable to a constituency that requires them to provide them with direct benefits.

In contrast, activists from the non-governmental sector are motivated by ideals, are free of accountability and gain legitimacy from being political outsiders. Therefore, the interests of unions are not likely to align well with the interests of those who draft and monitor corporate codes of conduct.

Arguing against the idea that high union wages necessarily make manufacturing uncompetitive in a globalized economy is labor lawyer Thomas Geoghegan. Busting

unions, in the U.S. manner, as the prime way of competing with China and other countries [does not work]. It's no accident that the social democracies, Sweden, France, and Germany, which kept on paying high wages, now have more industry than the U.S. or the UK. … [T]hat's what the U.S. and the UK did: they smashed the unions, in the belief that they had to compete on cost. The result? They quickly ended up wrecking their industrial base.

Unions have made some attempts to organize across borders. Eder observes that transnational organizing is not a new phenomenon but has been facilitated by technological change. Nevertheless, he claims that while unions pay lip service to global solidarity, they still act largely in their national self-interest. He argues that unions in the global North are becoming increasingly depoliticized while those in the South grow politically, and that global differentiation of production processes leads to divergent strategies and interests in different regions of the world. These structural differences tend to hinder effective global solidarity. However, in light of the weakness of international labor, Herod writes that globalization of production need not be met by a globalization of union strategies in order to be contained. Herod also points out that local strategies, such as the United Auto Workers' strike against General Motors in 1998, can sometimes effectively interrupt global production processes in ways that they could not before the advent of widespread market integration. Thus, workers need not be connected organizationally to others around the world to effectively influence the behavior of a transnational corporation.

Impact

A 2018 study in the Economic History Review found that the rise of labor unions in the 1930s and 1940s reduced income inequality. A 2020 study found that congressional representatives were more responsive to the interests of the poor in districts with higher unionization rates. Another 2020 study found an association between state level adoption of parental leave legislation and labor union strength.

A 2020 study in the American Journal of Political Science found that when white people obtain union membership, they become less racially resentful.