| Acute myeloid leukemia | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Acute myelogenous leukemia, acute nonlymphocytic leukemia (ANLL), acute myeloblastic leukemia, acute granulocytic leukemia |

| |

| Bone marrow aspirate showing acute myeloid leukemia, arrows indicate Auer rods | |

| Specialty | Hematology, oncology |

| Symptoms | Feeling tired, shortness of breath, easy bruising and bleeding, increased risk of infection |

| Usual onset | All ages, most frequently ~65–75 years old |

| Risk factors | Smoking, previous chemotherapy or radiation therapy, myelodysplastic syndrome, benzene |

| Diagnostic method | Bone marrow aspiration, blood test |

| Treatment | Chemotherapy, radiation therapy, stem cell transplant |

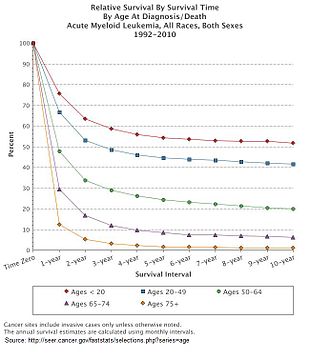

| Prognosis | Five-year survival ~29% (US, 2017) |

| Frequency | 1 million (2015) |

| Deaths | 147,100 (2015) |

Acute myeloid leukemia (AML) is a cancer of the myeloid line of blood cells, characterized by the rapid growth of abnormal cells that build up in the bone marrow and blood and interfere with normal blood cell production. Symptoms may include feeling tired, shortness of breath, easy bruising and bleeding, and increased risk of infection. Occasionally, spread may occur to the brain, skin, or gums. As an acute leukemia, AML progresses rapidly, and is typically fatal within weeks or months if left untreated.

Risk factors include smoking, previous chemotherapy or radiation therapy, myelodysplastic syndrome, and exposure to the chemical benzene. The underlying mechanism involves replacement of normal bone marrow with leukemia cells, which results in a drop in red blood cells, platelets, and normal white blood cells. Diagnosis is generally based on bone marrow aspiration and specific blood tests. AML has several subtypes for which treatments and outcomes may vary.

The first-line treatment of AML is usually chemotherapy, with the aim of inducing remission. People may then go on to receive additional chemotherapy, radiation therapy, or a stem cell transplant. The specific genetic mutations present within the cancer cells may guide therapy, as well as determine how long that person is likely to survive.

In 2015, AML affected about one million people, and resulted in 147,000 deaths globally. It most commonly occurs in older adults. Males are affected more often than females. The five-year survival rate is about 35% in people under 60 years old and 10% in people over 60 years old. Older people whose health is too poor for intensive chemotherapy have a typical survival of five to ten months. It accounts for roughly 1.1% of all cancer cases, and 1.9% of cancer deaths in the United States.

Signs and symptoms

Most signs and symptoms of AML are caused by the crowding out in bone marrow of space for normal blood cells to develop. A lack of normal white blood cell production makes people more susceptible to infections. A low red blood cell count (anemia) can cause fatigue, paleness, shortness of breath and palpitations. A lack of platelets can lead to easy bruising, bleeding from the nose (epistaxis), small blood vessels on the skin (petechiae) or gums, or bleeding with minor trauma. Other symptoms may include fever, fatigue worse than what can be attributed to anaemia alone, weight loss and loss of appetite.

Enlargement of the spleen may occur in AML, but it is typically mild and asymptomatic. Lymph node swelling is rare in most types of AML, except for AMML. The skin can be involved in the form of leukemia cutis; Sweet's syndrome; or non-specific findings flat lesions (macules), raised lesion papules), pyoderma gangrenosum and vasculitis.

Some people with AML may experience swelling of the gums because of infiltration of leukemic cells into the gum tissue. Involvement of other parts of the body such as the gastrointestinal tract, respiratory tract and other parts is possible but less common. One area which has particular importance for treatment is whether there is involvement of the meninges around the central nervous system.

Risk factors

Most cases of AML do not have exposure to an identified risk factors. That said, a number of risk factors for developing AML have been identified. These include other blood disorders, chemical exposures, ionizing radiation, and genetic risk factors. Where a defined exposure to past chemotherapy, radiotherapy , toxin or haematologic malignancy is known, this is termed secondary AML.

Other blood disorders

Other blood disorders, particularly myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) and less commonly myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPN), can evolve into AML; the exact risk depends on the type of MDS/MPN. The presence of asymptomatic clonal hematopoiesis also raises the risk of transformation into AML.

Chemical exposure

Exposure to anticancer chemotherapy, in particular alkylating agents, can increase the risk of subsequently developing AML. Other chemotherapy agents, including fludarabine, and topoisomerase II inhibitors are also associated with the development of AML; most commonly after 4–6 years and 1–3 years respectively. These are often associated with specific chromosomal abnormalities in the leukemic cells.

Other chemical exposures associated with the development of AML include benzene, chloramphenicol and phenylbutazone.

Radiation

High amounts of ionizing radiation exposure, such as that used for radiotherapy used to treat some forms of cancer, can increase the risk of AML. People treated with ionizing radiation after treatment for prostate cancer, non-Hodgkin lymphoma, lung cancer, and breast cancer have the highest chance of acquiring AML, but this increased risk returns to the background risk observed in the general population after 12 years. Historically, survivors of the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki had an increased rate of AML, as did radiologists exposed to high levels of X-rays prior to the adoption of modern radiation safety practices.

Genetics

Most cases of AML arise spontaneously, however there are some genetic mutations associated with an increased risk. Several congenital conditions increase the risk of leukemia; the most common is Down syndrome, with other more rare conditions including Fanconi anemia, Bloom syndrome and ataxia-telangiectasia (all characterised by problems with DNA repair), and Kostmann syndrome.

Other factors

Being overweight and obese increase the risk of developing AML, as does any amount of active smoking. For reasons that may relate to substance or radiation exposure, certain occupations have a higher rate of AML; particularly work in the nuclear power industry, electronics of computer manufacturing, fishing and animal slaughtering and processing.

Diagnosis

A complete blood count, which is a blood test, is one of the initial steps in the diagnosis of AML. It may reveal both an excess of white blood cells (leukocytosis) or a decrease (leukopenia), and a low red blood cell count (anemia) and low platelets (thrombocytopenia) can also be commonly seen. A blood film may show leukemic blast cells. Inclusions within the cells called Auer rods, when seen, make the diagnosis highly likely. A definitive diagnosis requires a bone marrow aspiration and biopsy.

Bone marrow is examined under light microscopy, as well as flow cytometry, to diagnose the presence of leukemia, to differentiate AML from other types of leukemia (e.g. acute lymphoblastic leukemia), and to provide information about how mature or immature the affected cells are that can assist in classifying the subtype of disease. A sample of marrow or blood is typically also tested for chromosomal abnormalities by routine cytogenetics or fluorescent in situ hybridization. Genetic studies may also be performed to look for specific mutations in genes such as FLT3, nucleophosmin, and KIT, which may influence the outcome of the disease.

Cytochemical stains on blood and bone marrow smears are helpful in the distinction of AML from ALL, and in subclassification of AML. The combination of a myeloperoxidase or Sudan black stain and a nonspecific esterase stain will provide the desired information in most cases. The myeloperoxidase or Sudan black reactions are most useful in establishing the identity of AML and distinguishing it from ALL. The nonspecific esterase stain is used to identify a monocytic component in AMLs and to distinguish a poorly differentiated monoblastic leukemia from ALL.

The standard classification scheme for AML is the World Health Organization (WHO) system. According to the WHO criteria, the diagnosis of AML is established by demonstrating involvement of more than 20% of the blood and/or bone marrow by leukemic myeloblasts, except in three forms of acute myeloid leukemia with recurrent genetic abnormalities: t(8;21), inv(16) or t(16;16), and acute promyelocytic leukemia with PML-RARA, in which the presence of the genetic abnormality is diagnostic irrespective of blast percent. Myeloid sarcoma is also considered a subtype of AML independently of the blast count. The older French-American-British (FAB) classification, which is no longer widely used, is a bit more stringent, requiring a blast percentage of at least 30% in bone marrow or peripheral blood for the diagnosis of AML.

Because acute promyelocytic leukemia has the highest curability and requires a unique form of treatment, it is important to quickly establish or exclude the diagnosis of this subtype of leukemia. Fluorescent in situ hybridization performed on blood or bone marrow is often used for this purpose, as it readily identifies the chromosomal translocation [t(15;17)(q22;q12);] that characterizes APL. There is also a need to molecularly detect the presence of PML/RARA fusion protein, which is an oncogenic product of that translocation.

World Health Organization

The WHO classification of AML attempts to be more clinically useful and to produce more meaningful prognostic information than the FAB criteria. Each of the WHO categories contains numerous descriptive subcategories of interest to the hematopathologist and oncologist; however, most of the clinically significant information in the WHO schema is communicated via categorization into one of the subtypes listed below.

The revised fourth edition of the WHO Classification of Tumours of Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues was released in 2016. This classification, which is based on a combination of genetic and immunophenotypic markers and morphology, defines the subtypes of AML and related neoplasms as:

| Name | Description | ICD-O |

|---|---|---|

| Acute myeloid leukemia with recurrent genetic abnormalities | Includes:

|

Multiple |

| AML with myelodysplasia-related changes | This category includes people who have had a prior documented myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) or myeloproliferative disease

(MPD) that then has transformed into AML; who have cytogenetic

abnormalities characteristic for this type of AML (with previous history

of MDS or MPD that has gone unnoticed in the past, but the cytogenetics

is still suggestive of MDS/MPD history); or who have AML with

morphologic features of myelodysplasia (dysplastic changes in multiple cell lines).

People who have previously received chemotherapy or radiation treatment for a non-MDS/MPD disease, and people who have genetic markers associated with AML with recurrent genetic abnormalities, are excluded from this category. This category of AML occurs most often in elderly people and often has a worse prognosis. Cytogenetic markers for AML with myelodysplasia-related changes include:

|

M9895/3 |

| Therapy-related myeloid neoplasms | This category includes people who have had prior chemotherapy and/or radiation and subsequently develop AML or MDS. These leukemias may be characterized by specific chromosomal abnormalities, and often carry a worse prognosis. | M9920/3 |

| Myeloid sarcoma | This category includes myeloid sarcoma. |

|

| Myeloid proliferations related to Down syndrome | This category includes "transient abnormal myelopoiesis" and "myeloid leukemia associated with Down syndrome". In young children, myeloid leukemia associated with Down syndrome has a much better prognosis than other types of childhood AML. The prognosis in older children is similar to conventional AML. |

|

| AML not otherwise categorized | Includes subtypes of AML that do not fall into the above categories: | M9861/3 |

Acute leukemias of ambiguous lineage (also known as mixed phenotype or biphenotypic acute leukemia) occur when the leukemic cells can not be classified as either myeloid or lymphoid cells, or where both types of cells are present.

French-American-British

The French-American-British (FAB) classification system divides AML into eight subtypes, M0 through to M7, based on the type of cell from which the leukemia developed and its degree of maturity. AML of types M0 to M2 may be called acute myeloblastic leukemia. Classification is done by examining the appearance of the malignant cells with light microscopy and/or by using cytogenetics to characterize any underlying chromosomal abnormalities. The subtypes have varying prognoses and responses to therapy.

While the terminology of the FAB system is still sometimes used, and it remains a valuable diagnostic tool in areas without access to genetic testing, this system has largely become obsolete in favor of the WHO classification, which correlates more strongly with treatment outcomes.

Six FAB subtypes (M1 through to M6) were initially proposed in 1976, although later revisions added M7 in 1985 and M0 in 1987.

| Type | Name | Cytogenetics | Percentage of adults with AML | Immunophenotype | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CD14 | CD15 | CD33 | HLA-DR | Other | ||||

| M0 | acute myeloblastic leukemia, minimally differentiated |

|

5% | − | − | + | + | MPO − |

| M1 | acute myeloblastic leukemia, without maturation |

|

15% | − | − | + | + | MPO + |

| M2 | acute myeloblastic leukemia, with granulocytic maturation | t(8;21)(q22;q22), t(6;9) | 25% | − | + | + | + |

|

| M3 | promyelocytic, or acute promyelocytic leukemia (APL) | t(15;17) | 10% | − | + | + | − |

|

| M4 | acute myelomonocytic leukemia | inv(16)(p13q22), del(16q) | 20% | <45% | + | + | + |

|

| M4eo | myelomonocytic together with bone marrow eosinophilia | inv(16), t(16;16) | 5% | +/− |

|

+ | + | CD2+ |

| M5 | acute monoblastic leukemia (M5a) or acute monocytic leukemia (M5b) | del (11q), t(9;11), t(11;19) | 10% | >55% | + | + | + |

|

| M6 | acute erythroid leukemias, including erythroleukemia (M6a) and very rare pure erythroid leukemia (M6b) |

|

5% | − | +/− | +/− | +/− | Glycophorin + |

| M7 | acute megakaryoblastic leukemia | t(1;22) | 5% | − | − | + | +/− | CD41/CD61+ |

The morphologic subtypes of AML also include rare types not included in the FAB system, such as acute basophilic leukemia, which was proposed as a ninth subtype, M8, in 1999.

Pathophysiology

The malignant cell in AML is the myeloblast. In normal development of blood cells (hematopoiesis), the myeloblast is an immature precursor of myeloid white blood cells; a normal myeloblast will mature into a white blood cell such as an eosinophil, basophil, neutrophil or monocyte. In AML, though, a single myeloblast accumulates genetic changes which stop maturation, increase its proliferation, and protect if from programmed cell death (apoptosis). Much of the diversity and heterogeneity of AML is because leukemic transformation can occur at a number of different steps along the differentiation pathway. Genetic abnormalities or the stage at which differentiation was halted form part of modern classification systems.

Specific cytogenetic abnormalities can be found in many people with AML; the types of chromosomal abnormalities often have prognostic significance. The chromosomal translocations encode abnormal fusion proteins, usually transcription factors whose altered properties may cause the "differentiation arrest". For example, in APL, the t(15;17) translocation produces a PML-RARA fusion protein which binds to the retinoic acid receptor element in the promoters of several myeloid-specific genes and inhibits myeloid differentiation.

The clinical signs and symptoms of AML result from the growth of leukemic clone cells, which tends to interfere with the development of normal blood cells in the bone marrow. This leads to neutropenia, anemia, and thrombocytopenia. Other symptoms can arise from the infltration of malignant cells into parts of the body, such as the gingiva and skin.

Many cells develop mutations in genes that affect epigenetics, such as DNA methylation. When these mutations occur, it is likely in the early stages of AML. Such mutations include in the DNA demethylase TET2 and the metabolic enzymes IDH1 and IDH2, which lead to the generation of a novel oncometabolite, D-2-hydroxyglutarate, which inhibits the activity of epigenetic enzymes such as TET2. Epigenetic mutations may lead to the silencing of tumor suppressor genes and/or the activation of proto-oncogenes.

Treatment

First-line treatment of AML consists primarily of chemotherapy, and is divided into two phases: induction and consolidation. The goal of induction therapy is to achieve a complete remission by reducing the number of leukemic cells to an undetectable level; the goal of consolidation therapy is to eliminate any residual undetectable disease and achieve a cure. Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation is usually considered if induction chemotherapy fails or after a person relapses, although transplantation is also sometimes used as front-line therapy for people with high-risk disease. Efforts to use tyrosine kinase inhibitors in AML continue.

Induction

The goal of the induction phase is to reach a complete remission. Complete remission does not mean the disease has been cured; rather, it signifies no disease can be detected with available diagnostic methods. All subtypes except acute promyelocytic leukemia are usually given induction chemotherapy with cytarabine and an anthracycline such as daunorubicin or idarubicin. This induction chemotherapy regimen is known as "7+3" (or "3+7"), because the cytarabine is given as a continuous IV infusion for seven consecutive days while the anthracycline is given for three consecutive days as an IV push. Response to this treatment varies with age, with people aged less than 60 years having better remission rates between 60% and 80%, while older people having lower remission rates between 33% and 60%. Because of the toxic effects of therapy and a greater chance of AML resistance to this induction therapy, different treatment, such as that in clinical trials might be offered to people 60 – 65 years or older.

Acute promyelocytic leukemia is treated with all-trans-retinoic acid (ATRA) and either arsenic trioxide (ATO) monotherapy or an anthracycline. A syndrome similar to disseminated intravascular coagulation can develop during the initial few days of treatment or at the time the leukemia is diagnosed, and treatment can be complicated by a differentiation syndrome characterised by fever, fluid overload and low oxygen levels. Acute promyelocytic leukemia is considered curable. There is insufficient evidence to determine if prescribing ATRA in addition to chemotherapy to adults that suffer from acute myeloid leukaemia is helpful.

Consolidation

Even after complete remission is achieved, leukemic cells likely remain in numbers too small to be detected with current diagnostic techniques. If no consolidation therapy or further postremission is given, almost all people with AML will eventually relapse.

The specific type of postremission therapy is individualized based on a person's prognostic factors (see above) and general health. For good-prognosis leukemias (i.e. inv(16), t(8;21), and t(15;17)), people will typically undergo an additional three to five courses of intensive chemotherapy, known as consolidation chemotherapy. This generally involves cytarabine, with the doses administered being higher in younger patients, who are less likely to develop toxicity related to this treatment.

Stem cell transplantation

Stem cell transplantation from a donor, called allogenic stem cell transplantation, is usually pursued if the prognosis is not considered favourable, a person can tolerate a transplant and has a suitable donor. The basis of allogenic stem cell transplantation is on a graft versus leukemia effect whereby graft cells stimulate an immune response against leukemia cells. Unfortunately this is accompanied by immune responses against other host organs, called a graft versus host disease.

Supportive treatment

Support is necessary throughout treatment because of problems associated with AML and also arising from treatment. Blood transfusions, including of red blood cells and platelets, are necessary to maintain health levels, preventing complications of anemia (from low red blood cells) and bleeding (from low platelets). AML leads to an increased risk of infections, particularly drug-resistant strains of bacteria and fungi. Antibiotics and antifungals can be used both to treat and to prevent these infections, particularly quinolones.

Adding aerobic physical exercises to the standard of care may result in little to no difference in the mortality, in the quality of life and in the physical functioning. These exercises may result in a slight reduction in depression. Furthermore, aerobic physical exercises probably reduce fatigue.

In pregnancy

AML is rare in pregnancy, affecting about 1 in 75,000 to 100,000 pregnant women. It is diagnosed and treated similarly to AML in non pregnancy, with a recommendation that it is treated urgently. However, treatment has significant implications for the pregnancy. First trimester pregnancy is considered unlikely to be viable; pregnancy during weeks 24 - 36 requires consideration of the benefits of chemotherapy to the mother against the risks to the foetus; and there is a recommendation to consider delaying chemotherapy in very late pregnancy (> 36 weeks). Some elements of supportive care, such as which antibiotics to prevent or treat infections, also change in pregnancy.

Prognosis

Multiple factors influence prognosis in AML, including the presence of specific mutations, and a person with AML's age. In the United States between 2011 - 2016, the median survival of a person with AML was 8.5 months, with the 5 year survival being 24%. This declines with age, with the poorer prognosis being associated with an age greater than 65 years, and the poorest prognosis seen in those aged 75 – 84.

As of 2001, cure rates in clinical trials have ranged from 20 to 45%; although clinical trials often include only younger people and those able to tolerate aggressive therapies. The overall cure rate for all people with AML (including the elderly and those unable to tolerate aggressive therapy) is likely lower. Cure rates for APL can be as high as 98%.

Relapse is common, and the prognosis varies. Many of the largest cancer hospitals in the country have access to clinical trials that can be used in refractory or relapsed disease. Another method that is becoming better engineered is undergoing a stem cell or bone marrow transplant. Transplants can often be used as a chance for a cure in patients that have high risk cytogentics or those that have relapsed. While there are two main types of transplants (allogeneic and autologus), patients with AML are more likely to undergo allogeneic transplants due to the compromised bone marrow and cellular nature of their disease.

Subtypes

Secondary AML has a worse prognosis, as does treatment-related AML arising after chemotherapy for another previous malignancy. Both of these entities are associated with a high rate of unfavorable genetic mutations.

Cytogenetics

Different genetic mutations are associated with a difference in outcomes. Certain cytogenetic abnormalities are associated with very good outcomes (for example, the (15;17) translocation in APL). About half of people with AML have "normal" cytogenetics; they fall into an intermediate risk group. A number of other cytogenetic abnormalities are known to associate with a poor prognosis and a high risk of relapse after treatment.

A large number of molecular alterations are under study for their prognostic impact in AML. However, only FLT3-ITD, NPM1, CEBPA and c-KIT are currently included in validated international risk stratification schema. These are expected to increase rapidly in the near future. FLT3 internal tandem duplications (ITDs) have been shown to confer a poorer prognosis in AML with normal cytogenetics. Several FLT3 inhibitors have undergone clinical trials, with mixed results. Two other mutations – NPM1 and biallelic CEBPA are associated with improved outcomes, especially in people with normal cytogenetics and are used in current risk stratification algorithms.

Researchers are investigating the clinical significance of c-KIT mutations in AML. These are prevalent, and potentially clinically relevant because of the availability of tyrosine kinase inhibitors, such as imatinib and sunitinib that can block the activity of c-KIT pharmacologically. It is expected that additional markers (e.g., RUNX1, ASXL1, and TP53) that have consistently been associated with an inferior outcome will soon be included in these recommendations. The prognostic importance of other mutated genes (e.g., DNMT3A, IDH1, IDH2) is less clear.

Other prognostic factors

Elevated lactate dehydrogenase level were also associated with poorer outcomes. Use of tobacco is associated with a person having a poorer prognosis, and people who are married and live together have a better prognosis. People who are treated at place with a higher volume of AML have a better prognosis than those who are treated at those in the lowest quartile. As with most forms of cancer, performance status (i.e. the general physical condition and activity level of the person) plays a major role in prognosis as well.

Epidemiology

AML is a relatively rare cancer. There were 19,950 new cases in the United States in 2016. AML accounts for 1.2% of all cancer deaths in the United States.

The incidence of AML increases by age and varyies between countries. The median age when AML is diagnosed varies between 63 and 71 years in the YK, Canada, Australia and Sweden, compared with 40 – 45 years in India, Brazil and Algeria.

AML accounts for about 90% of all acute leukemias in adults, but is rare in children. The rate of therapy-related AML (that is, AML caused by previous chemotherapy) is rising; therapy-related disease currently accounts for about 10–20% of all cases of AML. AML is slightly more common in men, with a male-to-female ratio of 1.3:1. Incidence is also seen to differ by ethnicity, with caucasians having higher recorded incidences and the lowest recorded incidences being in Pacific Islanders and native Alaksans. AML is slightly more common in men, who are 1.2 - 1.6 times more likely to develop AML in their lifetimes.

AML accounts for 34% of all leukemia cases in the UK, and around 2,900 people were diagnosed with the disease in 2011.

History

The first published description of a case of leukemia in medical literature dates to 1827 when French physician Alfred-Armand-Louis-Marie Velpeau described a 63-year-old florist who developed an illness characterized by fever, weakness, urinary stones, and substantial enlargement of the liver and spleen. Velpeau noted the blood of this person had a consistency "like gruel", and speculated the appearance of the blood was due to white corpuscles. In 1845, a series of people who died with enlarged spleens and changes in the "colors and consistencies of their blood" was reported by the Edinburgh-based pathologist J.H. Bennett; he used the term "leucocythemia" to describe this pathological condition.

The term "leukemia" was coined by Rudolf Virchow, the renowned German pathologist, in 1856. As a pioneer in the use of the light microscope in pathology, Virchow was the first to describe the abnormal excess of white blood cells in people with the clinical syndrome described by Velpeau and Bennett. As Virchow was uncertain of the etiology of the white blood cell excess, he used the purely descriptive term "leukemia" (Greek: "white blood") to refer to the condition.

Further advances in the understanding of AML occurred rapidly with the development of new technology. In 1877, Paul Ehrlich developed a technique of staining blood films which allowed him to describe in detail normal and abnormal white blood cells. Wilhelm Ebstein introduced the term "acute leukemia" in 1889 to differentiate rapidly progressive and fatal leukemias from the more indolent chronic leukemias. The term "myeloid" was coined by Franz Ernst Christian Neumann in 1869, as he was the first to recognize white blood cells were made in the bone marrow (Greek: μυєλός, myelos, lit. '(bone) marrow') as opposed to the spleen. The technique of bone marrow examination to diagnose leukemia was first described in 1879 by Mosler. Finally, in 1900, the myeloblast, which is the malignant cell in AML, was characterized by Otto Naegeli, who divided the leukemias into myeloid and lymphocytic.

In 2008, AML became the first cancer genome to be fully sequenced. DNA extracted from leukemic cells were compared to unaffected skin. The leukemic cells contained acquired mutations in several genes that had not previously been associated with the disease.