Survivalism is a social movement of individuals or groups (called survivalists or preppers) who proactively prepare for emergencies, such as natural disasters, as well as other disasters causing disruption to social order (that is, civil disorder) caused by political or economic crises. Preparations may anticipate short-term scenarios or long-term, on scales ranging from personal adversity, to local disruption of services, to international or global catastrophe. There is no bright line dividing general emergency preparedness from prepping in the form of survivalism (these concepts are a spectrum), but a qualitative distinction is often recognized whereby preppers/survivalists prepare especially extensively because they have higher estimations of the risk (odds) of catastrophes happening. Nonetheless, prepping can be as limited as preparing for a personal emergency (such as a job loss, storm damage to one's home, or getting lost in wooded terrain), or it can be as extensive as a personal identity or collective identity with a devoted lifestyle.

Survivalism's emphases are on self-reliance, stockpiling supplies, and gaining survival knowledge and skills. The stockpiling of supplies is itself a wide spectrum, from survival kits (ready bags, bug-out bags) that anyone should have, to entire bunkers in extreme cases.

Survivalists often acquire first aid and emergency medical/paramedic training, self-defense training (martial arts, firearm safety), and self-sufficiency training, and they often build structures such as survival retreats or underground shelters that may help them survive a catastrophic failure of society.

Use of the term survivalist dates from the early 1980s.

History

1930s to 1950s

The origins of the modern survivalist movement in the United Kingdom and the United States include government policies, threats of nuclear warfare, religious beliefs, and writers who warned of social or economic collapse in both non-fiction and apocalyptic and post-apocalyptic fiction.

The Cold War era civil defense programs promoted public atomic bomb shelters, personal fallout shelters, and training for children, such as the Duck and Cover films. The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church) has long directed its members to store a year's worth of food for themselves and their families in preparation for such possibilities, and the current teaching advises beginning with at least a three-month supply.

The Great Depression that followed the Wall Street Crash of 1929 is cited by survivalists as an example of the need to be prepared.

1960s

The increased inflation rate in the 1960s, the US monetary devaluation, the continued concern over a possible nuclear exchange between the US and the Soviet Union, and perceived increasing vulnerability of urban centers to supply shortages and other systems failures caused a number of primarily conservative and libertarian thinkers to promote individual preparations. Harry Browne began offering seminars on how to survive a monetary collapse in 1967, with Don Stephens (an architect) providing input on how to build and equip a remote survival retreat. He gave a copy of his original Retreater's Bibliography to each seminar participant.

Articles on the subject appeared in small-distribution libertarian publications such as The Innovator and Atlantis Quarterly. It was during this period that Robert D. Kephart began publishing Inflation Survival Letter (later renamed Personal Finance). For several years the newsletter included a continuing section on personal preparedness written by Stephens. It promoted expensive seminars around the US on similar cautionary topics. Stephens participated, along with James McKeever and other defensive investing, "hard money" advocates.

1970s

In the next decade Howard Ruff warned about socio-economic collapse in his 1974 book Famine and Survival in America. Ruff's book was published during a period of rampant inflation in the wake of the 1973 oil crisis. Most of the elements of survivalism can be found there, including advice on food storage. The book championed the claim that precious metals, such as gold and silver, have an intrinsic worth that makes them more usable in the event of a socioeconomic collapse than fiat currency. Ruff later published milder variations of the same themes, such as How to Prosper During the Coming Bad Years, a best-seller in 1979.

Firearms instructor and survivalist Colonel Jeff Cooper wrote on hardening retreats against small arms fire. In an article titled "Notes on Tactical Residential Architecture" in Issue #30 of P.S. Letter (April 1982), Cooper suggested using the "Vauban Principle", whereby projecting bastion corners would prevent miscreants from being able to approach a retreat's exterior walls in any blind spots. Corners with this simplified implementation of a Vauban Star are now called "Cooper Corners" by James Wesley Rawles, in honor of Jeff Cooper. Depending on the size of the group needing shelter, design elements of traditional European castle architecture, as well as Chinese Fujian Tulou and Mexican walled courtyard houses, have been suggested for survival retreats.

In both his book Rawles on Retreats and Relocation and in his survivalist novel, Patriots: A Novel of Survival in the Coming Collapse, Rawles describes in great detail retreat groups "upgrading" brick or other masonry houses with steel reinforced window shutters and doors, excavating anti-vehicular ditches, installing gate locks, constructing concertina wire obstacles and fougasses, and setting up listening post/observation posts (LP/OPs.) Rawles is a proponent of including a mantrap foyer at survival retreats, an architectural element that he calls a "crushroom".

Bruce D. Clayton and Joel Skousen have both written extensively on integrating fallout shelters into retreat homes, but they put less emphasis on ballistic protection and exterior perimeter security than Cooper and Rawles.

Other newsletters and books followed in the wake of Ruff's first publication. In 1975, Kurt Saxon began publishing a monthly tabloid-size newsletter called The Survivor, which combined Saxon's editorials with reprints of 19th century and early 20th century writings on various pioneer skills and old technologies. Kurt Saxon used the term survivalist to describe the movement, and he claims to have coined the term.

In the previous decade, preparedness consultant, survival bookseller, and California-based author Don Stephens popularized the term retreater to describe those in the movement, referring to preparations to leave cities for remote havens or survival retreats should society break down. In 1976, before moving to the Inland Northwest, he and his wife authored and published The Survivor's Primer & Up-dated Retreater's Bibliography.

For a time in the 1970s, the terms survivalist and retreater were used interchangeably. While the term retreater eventually fell into disuse, many who subscribed to it saw retreating as the more rational approach to conflict-avoidance and remote "invisibility". Survivalism, on the other hand, tended to take on a more media-sensationalized, combative, "shoot-it-out-with-the-looters" image.

One newsletter deemed by some to be one of the most important on survivalism and survivalist retreats in the 1970s was the Personal Survival ("P.S.") Letter (circa 1977–1982). Published by Mel Tappan, who also authored the books Survival Guns and Tappan on Survival. The newsletter included columns from Tappan himself as well as notable survivalists such as Jeff Cooper, Al J Venter, Bruce D. Clayton, Nancy Mack Tappan, J.B. Wood (author of several gunsmithing books), Karl Hess, Janet Groene (travel author), Dean Ing, Reginald Bretnor, and C.G. Cobb (author of Bad Times Primer). The majority of the newsletter revolved around selecting, constructing, and logistically equipping survival retreats. Following Tappan's death in 1980, Karl Hess took over publishing the newsletter, eventually renaming it Survival Tomorrow.

In 1980, John Pugsley published the book The Alpha Strategy. It was on The New York Times Best Seller list for nine weeks in 1981. After 28 years in circulation, The Alpha Strategy remains popular with survivalists, and is considered a standard reference on stocking food and household supplies as a hedge against inflation and future shortages.

In addition to hardcopy newsletters, in the 1970s survivalists established their first online presence with BBS and Usenet forums dedicated to survivalism and survival retreats.

1980s

Further interest in the survivalist movement peaked in the early 1980s, with Howard Ruff's book How to Prosper During the Coming Bad Years and the publication in 1980 of Life After Doomsday by Bruce D. Clayton. Clayton's book, coinciding with a renewed arms race between the United States and Soviet Union, marked a shift in emphasis in preparations made by survivalists away from economic collapse, famine, and energy shortages—which were concerns in the 1970s—to nuclear war. In the early 1980s, science fiction writer Jerry Pournelle was an editor and columnist for Survive, a survivalist magazine, and was influential in the survivalist movement. Ragnar Benson's 1982 book Live Off The Land In The City And Country suggested rural survival retreats as both a preparedness measure and conscious lifestyle change.

1990s

Interest in the movement picked up during the Clinton administration due in part to the debate surrounding the Federal Assault Weapons Ban and the ban's subsequent passage in 1994. The interest peaked again in 1999 triggered by fears of the Y2K computer bug. Before extensive efforts were made to rewrite computer programming code to mitigate the effects, some writers such as Gary North, Ed Yourdon, James Howard Kunstler, and investments' advisor Ed Yardeni anticipated widespread power outages, food and gasoline shortages, and other emergencies. North and others raised the alarm because they thought Y2K code fixes were not being made quickly enough. While a range of authors responded to this wave of concern, two of the most survival-focused texts to emerge were Boston on Y2K (1998) by Kenneth W. Royce, and Mike Oehler's The Hippy Survival Guide to Y2K. Oehler is an underground living advocate, who also authored The $50 and Up Underground House Book, which has long been popular in survivalist circles.

2000s

Another wave of survivalism began after the September 11, 2001, attacks and subsequent bombings in Bali, Madrid, and London. This resurgence of interest in survivalism appears to be as strong as the 1970s era focus on the topic. The fear of war, avian influenza, energy shortages, environmental disasters, and global climate change, coupled with economic uncertainty and the apparent vulnerability of humanity after the 2004 Indian Ocean earthquake and tsunami and Hurricane Katrina, have increased interest in survivalism topics.

Many books were published in the wake of the Great Recession from 2008 and later offering survival advice for various potential disasters, ranging from an energy shortage and crash to nuclear or biological terrorism. In addition to the 1970s-era books, blogs and Internet forums are popular ways of disseminating survivalism information. Online survival websites and blogs discuss survival vehicles, survival retreats, emerging threats, and list survivalist groups.

Economic troubles emerging from the credit collapse triggered by the 2007 US subprime mortgage lending crisis and global grain shortages prompted a wider cross-section of the populace to prepare.

The advent of H1N1 Swine Flu in 2009 piqued interest in survivalism, significantly boosting sales of preparedness books and making survivalism more mainstream.

These developments led Gerald Celente, founder of the Trends Research Institute, to identify a trend that he calls "neo-survivalism". He explained this phenomenon in a radio interview with Jim Puplava on December 18, 2009:

When you go back to the last depressing days when we were in a survival mode, the last one the Y2K of course, before the 1970s, what had happened was you only saw this one element of survivalist, you know, the caricature, the guy with the AK-47 heading to the hills with enough ammunition and pork and beans to ride out the storm. This is a very different one from that: you're seeing average people taking smart moves and moving in intelligent directions to prepare for the worst. (...) So survivalism in every way possible. Growing your own, self-sustaining, doing as much as you can to make it as best as you can on your own and it can happen in urban area, sub-urban area or the ex-urbans. And it also means becoming more and more tightly committed to your neighbors, your neighborhood, working together and understanding that we're all in this together and that when we help each other out that's going to be the best way forward.

This last aspect is highlighted in The Trends Research Journal: "Communal spirit intelligently deployed is the core value of Neo-Survivalism".

2010s

Television shows such as the National Geographic Channel's Doomsday Preppers emerged to capitalize on what Los Angeles Times entertainment contributor Mary McNamara dubbed "today's zeitgeist of fear of a world-changing event". After the 2012 Sandy Hook Elementary School shooting, the "prepper" community worried they would face public scrutiny after it was revealed the perpetrator's mother was a survivalist.

2020s

During the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, which was declared a Public Health Emergency of International Concern by the World Health Organization in early 2020, survivalism has received renewed interest, even by those who are not traditionally considered preppers.

Outline of scenarios and outlooks

Survivalism is approached by its adherents in different ways, depending on their circumstances, mindsets, and particular concerns for the future. The following are characterizations, although most (if not all) survivalists fit into more than one category:

- Safety-preparedness-oriented

While some survivalists believe in long-term viability of Western civilization, they learn principles and techniques needed for surviving life-threatening situations that can occur at any time and place. They prepare for such calamities that could result in physical harm or requiring immediate attention or defense from threats. These disasters could be biotic or abiotic. Survivalists combat disasters by attempting to prevent and mitigate damage caused by these factors.

- Wilderness survival emphasis

This group stresses being able to stay alive for indefinite periods in life-threatening wilderness scenarios, including plane crashes, shipwrecks, and being lost in the woods. Concerns are: thirst, hunger, climate, terrain, health, stress, and fear. The rule of 3 is often emphasized as common practice for wilderness survival. The rule states that a human can survive: 3 minutes without air, 3 hours without shelter, 3 days without water, 3 weeks without food.

- Self-defense-driven

This group focuses on surviving brief encounters of violent activity, including personal protection and its legal ramifications, danger awareness, John Boyd's cycle (also known as the OODA loop—observe, orient, decide and act), martial arts, self-defense tactics and tools (both lethal and non-lethal). These survivalist tactics are often firearm-oriented, in order to ensure a method of defense against attackers or home invasion.

- Natural disaster, brief

This group consists of people who live in tornado, hurricane, flood, wildfire, earthquake or heavy snowfall-prone areas and want to be prepared for possible emergencies. They invest in material for fortifying structures and tools for rebuilding and constructing temporary shelters. While assuming the long-term continuity of society, some may have invested in a custom-built shelter, food, water, medicine, and enough supplies to get by until contact with the rest of the world resumes following a natural emergency.

- Natural disaster, prolonged

This group is concerned with weather cycles of 2–10 years, which have happened historically and can cause crop failures. They might stock several tons of food per family member and have a heavy-duty greenhouse with canned non-hybrid seeds.

- Natural disaster, indefinite/multi-generational

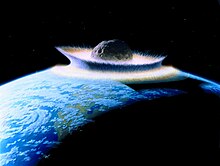

This group considers an end to society as it exists today under possible scenarios including global warming, global cooling, environmental degradation, warming or cooling of gulf stream waters, or a period of severely cold winters caused by a supervolcano, an asteroid strike, or Nuclear winter.

- Bio-chem scenario

This group is concerned with the spread of fatal diseases, biological agents, and nerve gases, including COVID-19, swine flu, E. coli, botulism, dengue fever, Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease, SARS, rabies, Hantavirus, anthrax, plague, cholera, HIV, ebola, Marburg virus, Lassa virus, sarin, and VX. In response, they might own NBC (nuclear, biological and chemical) full-face respirators, polyethylene coveralls, PVC boots, nitrile gloves, plastic sheeting and duct tape.

- Monetary disaster investors

Monetary disaster investors believe the Federal Reserve system is fundamentally flawed. Newsletters suggest hard assets of gold and silver bullion, coins, and other precious-metal-oriented investments such as mining shares. Survivalists prepare for paper money to become worthless through hyperinflation. As of late 2009 this is a popular scenario. Many will stockpile bullion in preparation for a market crash that would destroy the value of global currencies.

- Biblical eschatologist

These individuals study End Times prophecy and believe that one of various scenarios might occur in their lifetime. While some Christians (and even people of other religions) believe that the Rapture will follow a period of Tribulation, others believe that the Rapture is imminent and will precede the Tribulation ("Pre-Trib Rapture"). There is a wide range of beliefs and attitudes in this group. They run the gamut from pacifist to armed camp, and from having no food stockpiles (leaving their sustenance up to God's providence) to storing decades' worth of food. After a decree by the Mormon Prophet, devout Mormons have for decades stored 2 years of food in anticipation of the upheaval of the Second Coming of Christ to stave off famine and pestilence.

- Peak-oil doomers

This group believes that peak oil is a near term threat to Western civilization, and take appropriate measures, usually involving relocation to an agriculturally self-sufficient survival retreat.

- Rawlesian

Followers of James Wesley Rawles often prepare for multiple scenarios with fortified and well-equipped rural survival retreats. This group anticipates a near-term crisis and seek to be well-armed as well as ready to dispense charity in the event of a disaster. Most take a "deep larder" approach and store food to last years, and a central tenet is geographic seclusion in the northern US intermountain region. They emphasize practical self-sufficiency and homesteading skills.

- Legal-continuity-oriented

This group has a primary concern with maintaining some form of legal system and social cohesion after a breakdown in the technical infrastructure of society. They are interested in works like The Postman by David Brin, Lewis Dartnell's The Knowledge: How to Rebuild Our World from Scratch, or Marcus B. Hatfield's The American Common Law: The Customary Law of the American Nation.

Common preparations

Common preparations include the creation of a clandestine or defensible retreat, haven, or bug out location (BOL) in addition to the stockpiling of non-perishable food, water (i.e. using water canisters), water-purification equipment, clothing, seed, firewood, defensive or hunting weapons, ammunition, agricultural equipment, and medical supplies. Some survivalists do not make such extensive preparations, and simply incorporate a "Be Prepared" outlook into their everyday life.

A bag of gear, often referred to as a "bug out bag" (BOB) or "get out of dodge" (G.O.O.D.) kit, can be created which contains basic necessities and useful items. It can be of any size, weighing as much as the user is able to carry.

Changing concerns and preparations

Survivalists' concerns and preparations have changed over the years. During the 1970s, fears were economic collapse, hyperinflation, and famine. Preparations included food storage and survival retreats in the country which could be farmed. Some survivalists stockpiled precious metals and barterable goods (such as common-caliber ammunition) because they assumed that paper currency would become worthless. During the early 1980s, nuclear war became a common fear, and some survivalists constructed fallout shelters.

In 1999, many people purchased electric generators, water purifiers, and several months' or years' worth of food in anticipation of widespread power outages because of the Y2K computer-bug. Between 2013 and 2019, many people purchased those same items in anticipation of widespread chaos following the 2016 election and the events leading up to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Instead of moving or making such preparations at home, many people also make plans to remain in their current locations until an actual breakdown occurs, when they will—in survivalist parlance—"bug out" or "get out of Dodge" to a safer location.

Religious beliefs

Other survivalists have more specialized concerns, often related to an adherence to apocalyptic religious beliefs.

Some evangelical Christians hold to an interpretation of Bible prophecy known as the post-tribulation rapture, in which the world will have to go through a seven-year period of war and global dictatorship known as the "Great Tribulation". Jim McKeever helped popularize survival preparations among this branch of evangelical Christians with his 1978 book Christians Will Go Through the Tribulation, and How To Prepare For It.

Similarly, some Catholics are preppers, based on Marian apparitions which speak of a great chastisement of humanity by God, particularly those associated with Our Lady of Fatima and Our Lady of Akita (which states "fire will fall from the sky and will wipe out a great part of humanity").

Mainstream emergency preparations

People who are not part of survivalist groups or apolitically oriented religious groups also make preparations for emergencies. This can include (depending on the location) preparing for earthquakes, floods, power outages, blizzards, avalanches, wildfires, terrorist attacks, nuclear power plant accidents, hazardous material spills, tornadoes, and hurricanes. These preparations can be as simple as following Red Cross and U.S. Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) recommendations by keeping a first aid kit, shovel, and extra clothes in the car, or by maintaining a small kit of emergency supplies, containing emergency food, water, a space blanket, and other essentials.

Mainstream economist and financial adviser Barton Biggs is a proponent of preparedness. In his 2008 book Wealth, War and Wisdom, Biggs has a gloomy outlook for the economic future, and suggests that investors take survivalist measures. In the book, Biggs recommends that his readers should "assume the possibility of a breakdown of the civilized infrastructure." He goes so far as to recommend setting up survival retreats: "Your safe haven must be self-sufficient and capable of growing some kind of food," Mr. Biggs writes. "It should be well-stocked with seed, fertilizer, canned food, medicine, clothes, etc. Think Swiss Family Robinson. Even in America and Europe, there could be moments of riot and rebellion when law and order temporarily completely breaks down."

For global catastrophic risks the costs of food storage become impractical for most of the population and for some such catastrophes conventional agriculture would not function due to the loss of a large fraction of sunlight (e.g. during nuclear winter or a supervolcano). In such situations, alternative food is necessary, which is converting natural gas and wood fiber to human edible food.

Survivalist terminology

Survivalists maintain their group identity by using specialized terminology not generally understood outside their circles. They often use military acronyms such as OPSEC and SOP, as well as terminology common among adherents to gun culture or the peak oil scenario. They also use terms that are unique to their own survivalist groups; common acronyms include:

- Alpha strategy: The practice of storing extra consumable items, as a hedge against inflation, and for use in barter and charity. Coined by John Pugsley.

- Ballistic wampum: Ammunition stored for barter purposes. Coined by Jeff Cooper.

- BOB: Bug-out bag. A pack containing everything needed to leave your home and get to a safe location until able to return safely to your home or residence. Whether heading to a BOL, Retreat, MAG, MAC or Redoubt.

- BOL: Bug-out location.

- BOV: Bug-out vehicle.

- Doomer: A peak oil adherent who believes in a Malthusian-scale social collapse.

- EDC: Everyday carry. What one carries at all times in case disaster strikes while one is out and about. Also refers to the normal carrying of a pistol for self-defense, or (as a noun) the pistol which is carried.

- EOTW: End of the world

- EROL: Excessive rule of law. Describes a situation where a government becomes oppressive and uses its powers and laws to control citizens. Sometimes this is used interchangeably with Martial Law

- Goblin: A criminal miscreant, coined (in the survivalist context) by Jeff Cooper.

- Golden/ Zombie horde: The anticipated large mixed horde of refugees and looters that will pour out of the metropolitan regions when SHTF. Coined (in the survivalist context) by James Wesley, Rawles.

- G.O.O.D.: Get out of Dodge (city). Fleeing urban areas in the event of a disaster. Coined by James Wesley Rawles.

- G.O.O.D. kit: Get out of Dodge kit. Synonymous with bug-out bag (BOB).

- INCH pack: I'm Never Coming Home pack (a sub-type of Bug Out Bag, often used by experts in the preparedness field). A pack containing everything needed to walk out into the woods and never return to society. It is an often heavy pack loaded with the gear needed to accomplish any wilderness task, from building shelter to gaining food, designed to allow someone to survive indefinitely in the woods. This requires skills as well as proper selection of equipment, as one can only carry so much. For example, instead of carrying food, one carries seeds, steel traps, a longbow, reel spinners and other fishing gear. Often INCH bag gear is designed to be more sustainable and durable, and include tools to fix gear. Common examples of this include files and Arkansas stones, or whetstones to sharpen knives, machetes, axes, and other blades. This is due to the idea that when using an INCH bag, materials and resupply will be rare, if not nonexistent, and as such tools need to be durable and self sustainable.

- PAW: Post-Apocalyptic World

- Pollyanna or Polly: Someone who is in denial about the disruption that might be caused by the advent of a large-scale disaster.

- Sheep: A person who trusts the government, institutions, or popular culture blindly. A similar term to Pollyanna.

- Prepper: A term often used as a synonym for survivalist that came into common usage during the early 2000s. Refers to one who is prepared or making preparations, such as by stockpiling food and ammunition. Can be contrasted slightly with survivalist, which emphasizes outdoor survival skills and self-sufficiency.

- SHTF: Shit hit/hits/hitting the fan.

- TEOTWAWKI: The end of the world as we know it. The expression is in use since at least the early 1960s (tagline to television film Threads (1984)). However, others claim the acronym may have been coined in 1987 by REM in their song "It's The End Of The World As We Know It" or 1996, in the Usenet newsgroup misc.survivalism.

- Uncivilization: A generic term for a great catastrophe.

- WROL: Without rule of law. Describes a potential lawless state of society.

- YOYO: You're on your own. Coined (in the survivalist context) by David Weed.

- Zombie: Unprepared, incidental survivors of a prepped-for disaster, "who feed on the preparations of others”

- Zombie apocalypse: Used by some preppers as a tongue-in-cheek metaphor for any natural or man-made disaster and "a clever way of drawing people's attention to disaster preparedness". The premise of the Zombie Squad is that "if you are prepared for a scenario where the walking corpses of your family and neighbors are trying to eat you alive, you will be prepared for almost anything." Though "there are some... who are seriously preparing for a zombie attack".

Media portrayal

Despite a lull following the end of the Cold War, survivalism has gained greater attention in recent years, resulting in increased popularity of the survivalist lifestyle, as well as increased scrutiny. A National Geographic show interviewing survivalists, Doomsday Preppers, was a "ratings bonanza" and "the network's most-watched series", yet Neil Genzlinger in The New York Times declared it an "absurd excess on display and at what an easy target the prepper worldview is for ridicule," noting, "how offensively anti-life these shows are, full of contempt for humankind." Nevertheless, this show occupies a key position in the discourse on preppers.

Gerald Celente, founder of the Trends Research Institute, noted how many modern survivalists deviate from the classic archetype, terming this new style "neo-survivalism"; "you know, the caricature, the guy with the AK-47 heading to the hills with enough ammunition and pork and beans to ride out the storm. This [neo-survivalist] is a very different one from that".

Perceived extremism

In popular culture, survivalism has been associated with paramilitary activities of the self-proclaimed "militias" in the United States. Some survivalists do take active defensive preparations that have military roots and that involve firearms, and this aspect is sometimes emphasized by the mass media. Kurt Saxon is one proponent of this approach to armed survivalism.

The potential for social collapse is often cited as motivation for being well-armed. Thus, some non-militaristic survivalists have developed an unintended militaristic image.

The U.S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS) in their "If You See Something, Say Something" campaign says that "the public should report only suspicious behavior and situations...rather than beliefs, thoughts, ideas, expressions, associations, or speech...". However, it is alleged that a DHS list of the characteristics of potential domestic terrorists used in law enforcement training includes "Survivalist literature (fictional books such as Patriots and One Second After are mentioned by name)", "Self-sufficiency (stockpiling food, ammo, hand tools, medical supplies)", and "Fear of economic collapse (buying gold and barter items)".

The Missouri Information Analysis Center (MIAC) issued on February 20, 2009, a report intended for law enforcement personnel only entitled "The Modern Militia Movement," which described common symbols and media, including political bumper stickers, associated with militia members and domestic terrorists. The report appeared March 13, 2009 on WikiLeaks and a controversy ensued. It was claimed that the report was derived purely from publicly available trend data on militias. However, because the report included political profiling, on March 23, 2009, an apology letter was issued, explaining that the report would be edited to remove the inclusion of certain components.

Worldwide

Individual survivalist preparedness and survivalist groups and forums—both formal and informal—are popular worldwide, most visibly in Australia, Austria, Belgium, Canada, Spain, France, Germany (often organized under the guise of "adventuresport" clubs), Italy, Netherlands, Sweden, Switzerland, the United Kingdom, South Africa and the United States.

Adherents of the back-to-the-land movement inspired by Helen and Scott Nearing, sporadically popular in the United States in the 1930s and 1970s (exemplified by The Mother Earth News magazine), share many of the same interests in self-sufficiency and preparedness. Back-to-the-landers differ from most survivalists in that they have a greater interest in ecology and counterculture. Despite these differences, The Mother Earth News was widely read by survivalists as well as back-to-the-landers during that magazine's early years, and there was some overlap between the two movements.

Anarcho-primitivists (often shortened to "Anprim, An-Prim, or AnPrim) share many characteristics with survivalists, most notably predictions of a pending ecological disaster. One of the most famous An-Prims being Theodore Kaczynski. Writers such as Derrick Jensen argue that industrial civilization is not sustainable, and will therefore inevitably bring about its own collapse. Non-anarchist writers such as Daniel Quinn, Joseph Tainter, and Richard Manning also hold this view. Some members of the Men Going Their Own Way subculture also promote off-grid living and believe that modern society is no longer liveable.

In popular culture

Survivalism and survivalist themes have been fictionalized in print, film, and electronic media.

The 1983 film The Survivors starring Walter Matthau, Robin Williams and Jerry Reed, used survivalism as part of its plot. Michael Gross and Reba McEntire played a survivalist married couple in the 1990 film Tremors and its sequels. Both of these films were comedies. The 1988 film Distant Thunder, starring John Lithgow, concerned Vietnam War veterans suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder who, similarly to some survivalists, withdrew to the wilderness.

Several television shows such as Doomsday Castle, Doomsday Preppers, Survivorman, Man vs Wild Man, Woman, Wild, Alone (TV series) and Naked and Afraid are based on the concept of survivalism.