From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

The United Mine Workers of America (UMW or UMWA) is a North American labor union

best known for representing coal miners. Today, the Union also

represents health care workers, truck drivers, manufacturing workers and

public employees in the United States and Canada.

Although its main focus has always been on workers and their rights,

the UMW of today also advocates for better roads, schools, and universal health care.

By 2014, coal mining had largely shifted to open pit mines in Wyoming,

and there were only 60,000 active coal miners. The UMW was left with

35,000 members, of whom 20,000 were coal miners, chiefly in underground

mines in Kentucky and West Virginia. However it was responsible for

pensions and medical benefits for 40,000 retired miners, and for 50,000

spouses and dependents.

The UMW was founded in Columbus, Ohio, on January 25, 1890, with the merger of two old labor groups, the Knights of Labor Trade Assembly No. 135 and the National Progressive Miners Union. Adopting the model of the American Federation of Labor

(AFL), the union was initially established as a three-pronged labor

tool: to develop mine safety; to improve mine workers' independence from

the mine owners and the company store; and to provide miners with collective bargaining power.

After passage of the National Recovery Act in 1933 during the Great Depression,

organizers spread throughout the United States to organize all coal

miners into labor unions. Under the powerful leadership of John L. Lewis, the UMW broke with the American Federation of Labor and set up its own federation, the CIO

(Congress of Industrial Organizations). Its organizers fanned out to

organize major industries, including automobiles, steel, electrical

equipment, rubber, paint and chemical, and fought a series of battles

with the AFL. The UMW grew to 800,000 members and was an element in the New Deal Coalition supporting Democratic President Franklin D. Roosevelt.

Lewis broke with Roosevelt in 1940 and left the CIO, leaving the UMW

increasingly isolated in the labor movement. During World War II the UMW

was involved in a series of major strikes and threatened walkouts that

angered public opinion and energized pro-business opponents. After the

war, the UMW concentrated on gaining large increases in wages, medical

services and retirement benefits for its shrinking membership, which was

contending with changes in technology and declining mines in the East.

Coal mining

Development of the Union

The UMW was founded at Columbus City Hall in Columbus, Ohio, on January 25, 1890, by the merger of two earlier groups, the Knights of Labor Trade Assembly No. 135 and the National Progressive Miners Union. It was modeled after the American Federation of Labor

(AFL). The Union's emergence in the 1890s was the culmination of

decades of effort to organize mine workers and people in adjacent

occupations into a single, effective negotiating unit. At the time coal

was one of the most highly sought natural resources, as it was widely

used to heat homes and to power machines in industries. The coal mines

were a competitive and dangerous place to work. With the owners imposing

reduced wages on a regular basis, in response to fluctuations in pricing, miners sought a group to stand up for their rights.

Early efforts

American Miners' Association

The first step in starting the union was the creation of the American Miners' Association. Scholars credit this organization with the beginning of the labor movement in the United States.

The membership of the group grew rapidly. "Of an estimated 56,000

miners in 1865, John Hinchcliffe claimed 22,000 as members of the AMA.

In response, the mine owners sought to stop the AMA from becoming more

powerful. Members of the AMA were fired and blacklisted from employment

at other mines. After a short time the AMA began to decline, and

eventually ceased operations.

Workingman's Benevolent Association

Another early labor union that arose in 1868 was the Workingmen's Benevolent Association. This union was distinguished as a labor union for workers mining anthracite

coal. The laborers formed the WBA to help improve pay and working

conditions. The main reason for the success of this group was the

president, John Siney,

who sought a way both to increase miners benefits while also helping

the operators earn a profit. They chose to limit the production of

anthracite to keep its price profitable. Because the efforts of the WBA

benefited the operators, they did not object when the union wanted to

take action in the mines; they welcomed the actions that would secure

their profit. Because the operators trusted the WBA, they agreed to the

first written contract between miners and operators.

As the union became more responsible in the operators' eyes, the union

was given more freedoms. As a result, the health and spirits of the

miners significantly improved.

The WBA could have been a very successful union had it not been for Franklin B. Gowen. In the 1870s Gowen owned the Reading Railroad,

and bought several coal mines in the area. Because he owned the coal

mines and controlled the means of transporting the coal, he was able to

slowly destroy the labor union. He did everything in his power to

produce the cheapest product and to ensure that non-union workers would

benefit. As conditions for the miners of the WBA worsened, the union

broke up and disappeared.

After the fall of the WBA, miners created many other small

unions, including the Workingman's Protective Association (WPA) and the

Miner's National Association (MNA). Although both groups had strong

ideas and goals, they were unable to gain enough support and

organization to succeed. The two unions did not last long, but provided

greater support by the miners for a union which could withstand and help

protect the workers' rights.

1870s

Although

many labor unions were failing, two predominant unions arose that held

promise to become strong and permanent advocates for the miners. The

main problem during this time was the rivalry between the two groups.

Because the National Trade Assembly #135, better known as the Knights of Labor,

and the National Federation of Miners and Mine Laborers were so opposed

to one another, they created problems for miners rather than solving

key issues.

National Trade Assembly #135

The Great Seal of the Knights of Labor.

This union was more commonly known as the Knights of Labor and began around 1870 in the Philadelphia, Pennsylvania area. The main problem with the Knights of Labor was its secrecy.

The members kept very private their affiliation and goals of the

Knights of Labor. Because both miners and operators could become

members, there was no commonality to unite the members. Also, the union

did not see strikes as a means to attain rights. To many people of the

time, a strike was the only way that they believed they would be heard.

The Knights of Labor tried to establish a strong and organized

union, so they set up a system of local assemblies, or LAs. There were

two main types of LAs, trade and mixed, with the trade LA being the most

common. Although this system was put into place to create order, it did

the opposite. Even though there were only two categories of LAs, there

were many sub-divisions. For the most part it was impossible to tell how

many trade and mixed LAs there were at a given time. Local assemblies

began to arise and fall all around, and many members began to question

whether or not the Knights of Labor was strong enough to fight for the

most important issue of the time, achieving an eight-hour work day.

National Federation of Miners and Mine Laborers

This

Union was formed by members of the Knights of Labor who realized that a

secret and unified group would not turn into a successful union. The

founders, John McBride,

Chris Evans and Daniel McLaughlin, believed that creating an eight-hour

work day would not only be beneficial for workers, but also as a means

to stop overproduction,

which would in turn help operators. The union was able to get

cooperation from operators because they explained that the miners wanted

better conditions because they felt as if they were part of the mining

industry and also wanted the company to grow. But in order for the

company to grow, the workers must have better conditions so that their

labor could improve and benefit the operators.

The union's first priority was to get a fair weighing system

within the mines. At a conference between the operators and the union,

the idea of a new system of scaling was agreed upon, but the system was

never implemented. Because the union did not deliver what it had

promised, it lost support and members.

1880s

During this

time, the rivalry between the two unions increased and eventually led

to the formation of the UMW. The first of many arguments arose after the

1886 joint conference. The Knights of Labor did not want the NTA #135

to be in control, so they went against a lot of their decisions. Also,

because the Knights of Labor were not in attendance at the conference,

they were not able to vote against actions which they thought

detrimental to gain rights for workers. The conference passed

resolutions requiring the Knights of Labor to give up their secrecy and

publicize material about its members and locations. The National

Federation held another conference in 1887 attended by both groups. But

it was unsuccessful in gaining agreement by the groups as to the next

actions to take. In 1888, Samuel Gompers was elected as President of the National Federation of Miners, and George Harris first vice president.

Throughout 1887-1888 many joint conferences were held to help

iron out the problems that the two groups were having. Many leaders of

each groups began questioning the morals of the other union. One leader,

William T. Lewis,

thought there needed to be more unity within the union, and that

competition for members between the two groups was not accomplishing

anything. As a result of taking this position, he was replaced by John

B. Rae as president of the NTA #135. This removal did not stop Lewis

however; he got many people together who had been also thrown out of the

Knights of Labor for trying to belong to both parties at once, along

with the National Federation, and created the National Progressive Union

of Miners and Mine Laborers (NPU).

Although the goal of the NPU in 1888 was ostensibly to create

unity between the miners, it instead drew a stronger line distinguishing

members of the NPU against those of the NTA #135. Because of the

rivalry, miners of one labor union would not support the strikes of

another, and many strikes failed. In December 1889, the president of the

NPU set up a joint conference for all miners. John McBride, the

president of NPU, suggested that the Knights of Labor should join the

NPU to form a stronger union. John B. Rae reluctantly agreed and decided

that the merged groups would meet on January 22, 1890.

Constitution of the Union: The Eleven Points

When the union was founded, the values of the UMWA were stated in the preamble:

We have founded the United Mine Workers of America for

the purpose of ... educating all mine workers in America to realize the

necessity of unity of action and purpose, in demanding and securing by

lawful means the just fruits of our toil.

The UMWA constitution listed eleven points as the union's goals:

- Payment of a salary commensurate with the dangerous work

conditions. This was one of the most important points of the

constitution.

- Payment to be made fairly in legal tender, not with company scrip.

- Provide safe working conditions, with operators to use the latest

technologies in order to preserve the lives and health of workers.

- Provide better ventilation systems to decrease black lung disease, and better drainage systems.

- Enforce safety laws and make it illegal for mines to have inadequate roof supports, or contaminated air and water in the mines.

- Limit regular hours to an eight-hour work day.

- End child labor, and strictly enforce the child labor law.

- Have accurate scales to weigh the coal products, so workers could be

paid fairly. Many operators had altered scales that showed a lighter

weight of coal than actually produced, resulting in underpayment to

workers. Miners were paid per pound of coal that they produced.

- Payment should be made in legal tender.

- Establish unbiased public police forces in the mine areas that were

not controlled by the operators. Many operators hired private police,

who were used to harass the mine workers and impose company power. In

company towns, the operators owned all the houses and controlled the

police force; they could arbitrarily evict workers and arrest them

unjustly.

- The workers reserved the right to strike, but would work with operators to reach reasonable conclusions to negotiations.

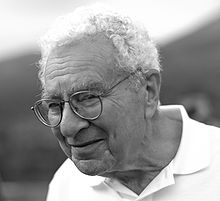

John L. Lewis

John L. Lewis

(1880 – 1969) was the highly combative UMW president who thoroughly

controlled the union from 1920 to 1960. A major player in the labor

movement and national politics, in the 1930s he used UMW activists to

organize new unions in autos, steel and rubber. He was the driving force

behind the founding of the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO). It established the United Steel Workers of America and helped organize millions of other industrial workers in the 1930s.

After resigning as head of the CIO in 1941, he took the Mine Workers out of the CIO in 1942 and in 1944 took the union into the American Federation of Labor (AFL). Lewis was a Republican, but he played a major role in helping Franklin D. Roosevelt

win re-election with a landslide in 1936, but as an isolationist

supported by Communist elements in the CIO, Lewis broke with Roosevelt

in 1940 on anti-Nazi foreign policy. (Following the 1939 German-Soviet pact of nonaggression, the Comintern had instructed communist parties in the West to oppose any support for nations at war with Nazi Germany.)

Lewis was a brutally effective and aggressive fighter and strike

leader who gained high wages for his membership while steamrolling over

his opponents, including the United States government. Lewis was one of

the most controversial and innovative leaders in the history of labor,

gaining credit for building the industrial unions of the CIO into a

political and economic powerhouse to rival the AFL, yet was widely hated

as he called nationwide coal strikes damaging the American economy in

the middle of World War II. His massive leonine head, forest-like

eyebrows, firmly set jaw, powerful voice, and ever-present scowl

thrilled his supporters, angered his enemies, and delighted cartoonists.

Coal miners for 40 years hailed him as the benevolent dictator who

brought high wages, pensions and medical benefits, and damn the critics.

Achievements

- An eight-hour work day was gained in 1898. The first ideas of this demand were outlined in point six of the constitution.

- The union achieved collective bargaining rights in 1933.

- Health and retirement benefits for the miners and their families were earned in 1946.

- In 1969, the UMWA convinced the United States Congress to enact the landmark Federal Coal Mine Health and Safety Act, which provided compensation for miners suffering from Black Lung Disease.

- Relatively high wages for unionized miners by the early 1960s.

List of strikes

The

union's history has numerous examples of strikes in which members and

their supporters clashed with company-hired strikebreakers and

government forces. The most notable include:

1890s

- Morewood massacre - April 3, 1891, in Morewood, Pennsylvania.

A crowd of mostly immigrant strikers were fired on by deputized members

of the 10th Regiment of the National Guard. At least ten strikers were

killed and dozens injured.

- Bituminous Coal Miners' Strike of 1894

- April 21, 1894. This nationwide strike was called when the union was

hardly four years old. Many of the workers salaries had been cut by 30%

and with the demand for coal down during the recession, workers were

desperate for work. The national guard was mobilized in several states

to prevent or control violent clashes between strikers and strike

breakers. The workers intended to strike for three weeks, hoping that

this would produce a demand for coal and their wages would increase with

its rising price. But, many union miners did not wish to cooperate with

this plan and did not return to work at all. The union appeared weak.

Other workers did not go out on strike, and with the demand low, they

were able to produce sufficient coal. By being efficient in the mines,

the operators saw no need to increase the wages of all the workers, and

did not seem to care if the strike would end.

By June the demand for coal began to increase, and some operators

decided to pay the workers their original salaries before the wage cut.

However, not all demands across the country were met, and some workers

continued to strike. The young union suffered damage in this uneven

effort. The most important goal of the 1894 strike was not the

restoration of wages, but rather the establishment of the UMWA as a

cooperation at a national level.

Early 1900s

- The five-month Coal Strike of 1902, led by the United Mine Workers and centered in eastern Pennsylvania, ended after direct intervention of President Theodore Roosevelt as a neutral arbitrator.

- 1903 Colorado coal strike - October 1903. The United Mine Workers

conducted a strike in Colorado, called in October 1903 by President

Mitchell, and lasting into 1904. The strike, while overshadowed by a

simultaneous strike conducted by the Western Federation of Miners among hard rock miners in the Cripple Creek District, contributed to the labor struggles in Colorado. These came to be known as the Colorado Labor Wars.

During the United Mine Workers effort, operators directed their private

forces to attack and beat traveling union officers and organizers,

which ultimately helped to break the strike. These beatings were a

mystery until publication of The Pinkerton Labor Spy (1907) by Morris Friedman, which revealed that the UMWA had been infiltrated by labor spies from the Pinkerton agency.

- 1908 Alabama coal strike - June–August 1908. Notable because the 18,000 UMWA-organized strikers, more than half of those working in the Birmingham District,

were racially integrated. That fact helped galvanize political

opposition to the strikers in the segregated state. The governor used

the Alabama State Militia to end the work stoppage. The union adopted

racial segregation of workers in Alabama in order to reduce the

political threat to the organization.

- Westmoreland County Coal Strike - 1910-1911, a 16-month coal strike in Pennsylvania led largely by Slovak

immigrant miners, this strike involved 15,000 coal miners. Sixteen

people were killed during the strike, nearly all of them striking miners

or members of their families.

- Colorado Coalfield War - September 1913–December 1914. A frequently violent strike against the John D. Rockefeller, Jr.-Colorado Fuel and Iron company. Many strikers and opposition were killed before the violent reached a peak following the 20 April 1914 Ludlow Massacre. An estimated 20 people, including women and children, were killed by armed police, hired guns, and Colorado National Guardsmen

who broke up a tent colony formed by families of miners who had been

evicted from company-owned housing. The strike was partially led by John R. Lawson, a UMWA organizer and saw the participation of famed activist Mother Jones. The UMWA purchased part of Ludlow site and constructed the Ludlow Monument in commemoration of those who died.

- Hartford coal mine riot

- July 1914. The surface plant of the Prairie Creek coal mine was

destroyed, and two non-union miners murdered by union miners and

sympathizers. The mine owners sued the local and national organizations

of the United Mine Workers Union. The national UMWA was found not

complicit, but the local was judged culpable of encouraging the rioters,

and made to pay US$2.1 million.

"KEEPING WARM"

Los Angeles Times

November 22, 1919

- United Mine Workers coal strike of 1919

- November 1, 1919. Some 400,000 members of the United Mine Workers

went on strike on November 1, 1919, although Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer had invoked the Lever Act,

a wartime measure criminalizing interference with the production or

transportation of necessities, and obtained an injunction against the

strike on October 31. The coal operators smeared the strikers with charges that Russian communist leaders Lenin and Trotsky had ordered the strike and were financing it, and some of the press repeated those claims.

- Matewan, West Virginia - May 19, 1920. 12 men were killed in a gunfight between town residents and the Baldwin–Felts Detective Agency, hired by mine owners. Director John Sayles directed a feature film, Matewan, based on these events.

- The 'Redneck War' - 1920-21. Generally viewed as beginning with the

Matewan Massacre, this conflict involved the struggle to unionize the

southwestern area of West Virginia. It led to the march of 10,000 armed

miners on the county seat at Logan. In the Battle of Blair Mountain, miners fought state militia, local police, and mine guards. These events are depicted in the novels Storming Heaven (1987) by Denise Giardina and Blair Mountain (2005) by Jonathan Lynn.

- 1920 Alabama coal strike, a lengthy, violent, expensive and fruitless attempt to achieve union recognition in the coal mines around Birmingham left 16 men dead; one black man was lynched.

- Herrin massacre occurred in June 1922 in Herrin, Illinois. 19 strikebreakers and 2 union miners were killed in mob action between June 21–22, 1922.

1922-1925 Nova Scotia strikes

In the 1920s, about 12,000 Nova Scotia miners were represented by the UMWA. These workers lived in very difficult economic circumstances in company towns. The Dominion Steel and Coal Corporation, also known as the British Empire Steel Corporation, or BESCO, controlled most coal mines and every steel mill in the province. BESCO was in financial difficulties and repeatedly attempted to reduce wages and bust the union.

Led by J. B. McLachlan,

miners struck in 1923, and were met by locally and

provincially-deployed troops. This would eventually lead to the federal

government introducing legislation limiting the civil use of troops.

In 1925 BESCO announced that it would not longer give credit at their company stores and that wages would be cut by 20%. The miners responded with a strike. This led to violence with company police firing on strikers, killing miner William Davis, as well as the looting and arson of company property.

This crisis led to the Nova Scotia government acting in 1937 to

improve the rights of all wage earners, and these reforms served as a

model across Canada, at both provincial and federal levels.

The Brookside Strike

In the summer of 1973, workers at the Duke Power-owned Eastover Mining Company's Brookside Mine and Prep Plant in Harlan County, Kentucky,

voted to join the union. Eastover management refused to sign the

contract and the miners went on strike. Duke Power attempted to bring in

replacement non-union workers or "scabs"

but many were blocked from entering the mine by striking workers and

their families on the picket line. Local judge F. Byrd Hogg was a coal

operator himself and consistently ruled for Eastover. During much of the

strike the mine workers' wives and children joined the picket lines.

Many were arrested, some hit by baseball bats, shot at, and struck by

cars. One striking miner, Lawrence Jones, was shot and killed by a Strikebreaker.

Three months after returning to work, the national UMWA contract

expired. On November 12, 1974, 120,000 miners nationwide walked off the

job. The nationwide strike was bloodless and a tentative contract was

achieved three weeks later. This opened the mines and reactivated the

railroad haulers in time for Christmas. These events are depicted in the

documentary film Harlan County, USA.

The Pittston strike

The Pittston Coal strike of 1989-1990 began as a result of a withdrawal of the Pittston Coal Group also known as the Pittston Company from the Bituminous Coal Operators Association

(BCOA) and a refusal of the Pittston Coal group to pay the health

insurance payments for miners who were already retired. The owner of the

Pittston company at the time, Paul Douglas, left the BCOA because he

wanted to be able to produce coal seven days a week and did not want his

company to pay the fee for the insurance.

The Pittson company was seen as having inadequate safety standards after the Buffalo Creek flood of 1972 in which 125 miners were killed.

The company also was very financially unstable and in debt. The mines

associated with the company were located mostly in Virginia, with mines

also in West Virginia and Kentucky.

On 31 January 1988 Douglas cut off retirement and health care

funds to about 1500 retired miners, widows of miners, and disabled

miners.

To avoid a strike, Douglas threatened that if a strike were to take

place, that the miners would be replaced by other workers. The UMW

called this action unjust and took the Pittston company to court.

Miners worked from January 1988 to April 1989 without a contract.

Tension in the company grew and on 5 April 1989 the workers declared a

strike.

Many months of both violent and nonviolent strike actions took place.

On 20 February 1990 a settlement was finally reached between the UMWA

and the Pittston Coal Company.

Internal conflict

The union's history has sometimes been marked by internal strife and corruption, including the 1969 murder of Joseph Yablonski, a reform candidate who lost a race for union president against incumbent W. A. Boyle, along with his wife and 25-year-old daughter. Boyle was later convicted of ordering these murders.

The killing of Yablonski resulted in the birth of a pro-democracy

movement called the "Miners for Democracy" (MFD) which swept Boyle and

his regime out of office, and replaced them with a group of leaders who

had been most recently rank and file miners.

Led by new president Arnold Miller,

the new leadership enacted a series of reforms which gave UMWA members

the right to elect their leaders at all levels of the union and to

ratify the contracts under which they worked.

Decline of labor unionism in mining

Decreased

faith in the UMW to support the rights of the miners caused many to

leave the union. Coal demand was curbed by competition from other energy

sources. The main cause of the decline in the union during the 1920s

and 1930s was the introduction of more efficient and easily produced

machines into the coal mines.

In previous years, less than 41% of coal was cut by the machines.

However, by 1930, 81% was being cut by the machines and now there were

machines that could also surface mine and load the coal into the trucks.

With more machines that could do the same labor, unemployment in the

mines grew and wages were cut back. As the problems grew, many people

did not believe that the UMW could ever

become as powerful as it was before the start of the war. The decline in the union began in the 1920s and continued through the 1930s. Slowly the membership of the UMWA grew back up in numbers, with the majority in District 50,

a catch-all district for workers in fields related to coal mining, such

as the chemical and energy industries. This district gained

organizational independence in 1961, and then fell into dispute with the

remainder of the union, leading in 1968 to its expulsion.

In the 1970s and after

Diana

Baldwin and Anita Cherry are believed to have been the first women to

work inside an American coal mine, and were the first women to work

inside a mine who were members of the UMW. They began that work in 1973

in Jenkins.

However, a general decline in union effectiveness characterized the

1970s and 1980s, leading to new kinds of activism, particularly in the

late 1970s. Workers saw their unions back down in the face of aggressive

management.

Other factors contributed to the decline in unionism generally

and UMW specifically. The coal industry was not prepared economically to

deal with such a drop in demand for coal. Demand for coal was very high

during World War II, but decreased dramatically after the war, in part

due to competition from other energy sources. In efforts to improve air

quality, municipal governments started to ban the use of coal as

household fuel. The end of wartime price controls introduced competition

to produce cheaper coal, putting pressure on wages.

These problems—perceived weakness of the unions, loss of control

over jobs, drop in demand, and competition—decreased the faith of miners

in their union.

By 1998 the UMW had about 240,000 members, half the number that it had

in 1946. As of the early 2000s, the union represents about 42 percent of all employed miners.

Affiliation with other unions

At some point before 1930, the UMW became a member of the American Federation of Labor.

The UMW leadership was part of the driving force to change the way

workers were organized, and the UMW was one of the charter members when

the new Congress of Industrial Organizations

was formed in 1935. However, the AFL leadership did not agree with the

philosophy of industrial unionization, and the UMW and nine other unions

that had formed the CIO were kicked out of the AFL in 1937.

In 1942, the UMW chose to leave the CIO,

and, for the next five years, were an independent union. In 1947, the

UMW once again joined the AFL, but the remarriage was a short one, as

the UMW was forced out of the AFL in 1948, and at that point, became the

largest non-affiliated union in the United States.

In 1982, Richard Trumka was elected the leader of the UMW. Trumka spent the 1980s healing the rift between the UMW and the now-conjoined AFL–CIO

(which was created in 1955 with the merger of the AFL and the CIO). In

1989, the UMW was again taken into the fold of the large union umbrella.

Political involvement

United Mine Workers meeting with Congressmember

Tom O'Halleran in 2020.

Throughout the years, the UMW has taken political stands and supported candidates to help achieve union goals.

The United Mine Workers ran candidate Frank Henry Sherman under the union banner in the 1905 Alberta general election. Sherman's candidacy was driven to appeal to the significant population of miners working in the camps of southern Alberta. He finished second in the riding of Pincher Creek.

The biggest conflict between the UMW and the government was while Franklin Roosevelt

was president of the United States and John L. Lewis was president of

the UMW. Originally, the two worked together well, but, after the 1937

strike of United Automobile Workers against General Motors, Lewis

stopped trusting Roosevelt, claiming that Roosevelt had gone back on his

word. This conflict led Lewis to resign as CIO

president. Roosevelt repeatedly won large majorities of the union

votes, even in 1940 when Lewis took an isolationist position on Europe,

as demanded by far-left union elements. Lewis denounced Roosevelt as a

power-hungry war monger, and endorsed Republican Wendell Willkie.

The tension between the two leaders escalated during World War

II. Roosevelt in 1943 was outraged when Lewis threatened a major strike

to end anthracite coal production needed by the war effort. He

threatened government intervention and Lewis retreated.

The UMW represents West Virginia coal miners and endorsed Joe Manchin (D-W.Va.) in the 2018 United States Senate election in West Virginia. In 2021 the union urged him to revisit his opposition to President Biden's Build Back Better Plan,

noting that the bill includes an extension of a fund that provides

benefits to coal miners suffering from black lung disease, which expires

at the end of the year. The UMWA also touted tax incentives that

encourage manufacturers to build facilities in coalfields that would

employ thousands of miners who lost their jobs.

"For those and other reasons, we

are disappointed that the bill will not pass," Cecil Roberts, the

union's president said. "We urge Senator Manchin to revisit his

opposition to this legislation and work with his colleagues to pass

something that will help keep coal miners working, and have a meaningful

impact on our members, their families, and their communities."

Recent elections

In 2008 the UMWA supported Barack Obama as the best candidate to help achieve more rights for the mine workers.

In 2012, the UMWA National COMPAC Council did not make an

endorsement in the election for President of the United States, citing

"Neither candidate has yet demonstrated that he will be on the side of

UMWA members and their families as president."

In 2014, the UMWA endorsed Kentucky Democrat Alison Lundergan Grimes for U.S. Senate.

List of presidents