Intrapersonal communication is the process by which an individual communicates within themselves, acting as both sender and receiver of messages, and encompasses the use of unspoken words to consciously engage in self-talk and inner speech.

Intrapersonal communication, also referred to as internal monologue, autocommunication, self-talk, inner speech, or internal discourse, is a person's inner voice which provides a running monologue of thoughts while they are conscious. It is usually tied to a person's sense of self. It is particularly important in planning, problem solving, self-reflection, self-image, critical thinking, emotions and subvocalization (reading in one's head). As a result, it is relevant to a number of mental disorders, such as depression, and treatments like cognitive behavioural therapy which seek to alleviate symptoms by providing strategies to regulate cognitive behaviour. It may reflect both conscious and subconscious beliefs.

Intrapersonal communication is a broad concept, encompassing all types of internal communication, including for example the biological, and electrochemical communication that occurs between neurons and hormones. Intrapersonal communication is also typical for religious or artistic works. Prayers, mantras and diaries are good examples. In organisations and corporations strategic plans and memos, for example, can function like mantras. But any text (or work) can become autocommunicational if it is able to be memorized and recited.

Intrapersonal communication provides individuals with the opportunity to participate in 'imaginative interactions', by which they silently engage in conversation with another person, often as a means of selecting and rehearsing their intended spoken interpersonal communication with the actual person. Intrapersonal communication also facilitates the process by which an individual engages in unspoken internal dialogue between different and sometimes conflicting attitudes, thoughts, and feelings, often as a way of resolving psychological conflicts and making decisions.

Definitions

Internal discourse is a constructive act of the human mind and a tool for discovering new knowledge and making decisions. Along with feelings such as joy, anger, fear, etc., and sensory awareness, it is one of the few aspects of the processing of information and other mental activities of which humans can be directly aware. Inner discourse is so prominent in the human awareness of mental functioning that it may often seem to be synonymous with "mind".

An inner discourse takes place much as would a discussion with a second person. One example could be looking for a lost item and retracing one's steps with themself and debating the sequence of those steps until the item is found. Purposeful inner discourse starts with statements about matters of fact and proceeds with logical rigor until a solution is achieved.

On this view of thinking, progress toward healthy thinking is made when one learns how to evaluate how well "statements of fact" are actually grounded, and when one learns how to avoid logical errors. But one must also take account of questions like why one is seeking a solution (such as asking why oneself wants to contribute money to a certain charity), and why one may keep getting results that turn out to be biased in fairly consistent patterns (such as asking why oneself never gives to charities that benefit a certain group).

Intrapersonal communication can involve speaking aloud as in reading aloud, repeating what one hears, the additional activities of speaking and hearing (in the third case of hearing again) what one thinks, reads or hears. This is considered normal although this does not exactly refer to intrapersonal communication as reading aloud may be a form of rhetorical exercise although expected in the relevant young age.

Development and Purpose

The Forward Model

In a theory of child development formulated by Lev Vygotsky, inner speech has a precursor in private speech (talking to oneself) at a young age.

In the 1920s, Swiss developmental psychologist Jean Piaget proposed the idea that private (or "egocentric") speech – speaking to oneself out loud – is the initial form of speech, from which "social speech" develops, and that it dies out as children grow up. In the 1930s, Russian psychologist Lev Vygotsky proposed instead that private speech develops from social speech, and later becomes internalised as an internal monologue, rather than dying out. This interpretation has come to be the more widely accepted, and is supported by empirical research.

Implicit in the idea of a social origin to inner speech is the possibility of "inner dialogue" – a form of "internal collaboration with oneself". However, Vygotsky believed inner speech takes on its own syntactic peculiarities, with heavy use of abbreviation and omission compared with oral speech (even more so compared with written speech).

Andy Clark (1998) writes that social language is "especially apt to be co-opted for more private purposes of [...] self-inspection and self-criticism", although others have defended the same conclusions on different grounds.

Human ability to talk to oneself and think in words is a major part of the human experience of consciousness. From an early age, individuals are encouraged by society to introspect carefully, but also to communicate the results of that introspection. Simon Jones and Charles Fernyhough cite research suggesting that human ability to talk themselves is very similar to regular speech. This theory originates with the developmental psychologist Lev Vygotsky, who observed that children will often narrate their actions out loud before eventually replacing the habit with the adult equivalent: sub-vocal articulation. During sub-vocal articulation, no sound is made but the mouth still moves. Eventually, adults may learn to inhibit their mouth movements, although they still experience the words as "inner speech".

Jones and Fernyhough cite other evidence for this hypothesis that inner speech is essentially like any other action. They mention that schizophrenics suffering auditory verbal hallucinations (AVH) need only open their mouths in order to disrupt the voices in their heads. To try and explain more about how inner speech works, but also what goes wrong with AVH patients, Jones and Fernyhough adapt what is known as the "forward model" of motor control, which uses the idea of "efferent copies".

In a forward model of motor control, the mind generates movement unconsciously. While information is sent to the necessary body parts, the mind sends a copy of that same information to other areas of the brain. This "efferent" copy could then be used to make predictions about upcoming movements. If the actual sensations match predictions, we experience the feeling of agency. If there is a mismatch between the body and its predicted position, perhaps due to obstructions or other cognitive disruption, no feeling of agency occurs.

Jones and Fernyhough believe that the forward model might explain AVH and inner speech. Perhaps, if inner speech is a normal action, then the malfunction in schizophrenic patients is not the fact that actions (i.e. voices) are occurring at all. Instead, it may be that they are experiencing normal, inner speech, but the generation of the predictive efferent copy is malfunctioning. Without an efferent copy, motor commands are judged as alien (i.e. one does not feel like they caused the action). This could also explain why an open mouth stops the experience of alien voices: When the patient opens their mouth, the inner speech motor movements are not planned in the first place.

Evolved to avoid silence

Joseph Jordania suggested that talking to oneself can be used to avoid silence. According to him, the ancestors of humans, like many other social animals, used contact calls to maintain constant contact with the members of the group, and a signal of danger was communicated through becoming silent and freezing. Because of the human evolutionary history, prolonged silence is perceived as a sign of danger and triggers a feeling of uneasiness and fear. According to Jordania, talking to oneself is only one of the ways to fill in prolonged gaps of silence in humans. Other ways of filling in prolonged silence are humming, whistling, finger drumming, or having TV, radio or music on all the time.

Neurological Correlates

The concept of internal monologue is not new, but the emergence of the functional MRI (magnetic resonance imaging) has led to a better understanding of the mechanisms of internal speech by allowing researchers to see localized brain activity.

Studies have revealed the differences in neural activations of inner dialogues versus those of monologues. Functional MRI imaging studies have shown that monologic internal speech involves the activation of the superior temporal gyrus and the left inferior frontal gyrus, which is the standard language system that is activated during any kind of speech. However, dialogical inner speech implicates several additional neural regions. Studies have indicated overlap with regions involved with thinking about other minds.

Regarding research on inner speech, Fernyhough stated "The new science of inner speech tells us that it is anything but a solitary process. Much of the power of self-talk comes from the way it orchestrates a dialogue between different points of view." Based on interpretation of functional medical-imaging, Fernyhough believes that language system of internal dialogue works in conjunction with a part of the social cognition system (localized in the right hemisphere close to the intersection between the temporal and parietal lobes). Neural imaging seems to support Vygotsky's theory that when individuals are talking aloud to themselves, they are having an actual conversation as though there were two participants. Intriguingly, individuals did not exhibit this same arrangement of neural activation with silent monologues. In past studies, it has been supported that these two brain hemispheres have different functions. Based on Functional magnetic resonance imaging studies, inner speech has been shown to more significant activations farther back in the temporal lobe, in Heschl's gyrus.

However, the results of neural imaging have to be taken with caution because the regions of the brain activated during spontaneous, natural internal speech diverge from those that are activated on demand. In research studies, individuals are asked to talk to themselves on demand, which is different from the natural development of inner speech within one's mind. The concept of internal monologue is a changing concept and is subjective to many implications with future studies.

Involvement in Mental Health

Negative and Positive Self-Talk

Negative self-talk (also known as unhelpful self-talk) refers to inner critical dialogue. It is based on beliefs about oneself that develop during childhood based on feedback of others, particularly parents. These beliefs create a lens through which the present is viewed. Examples of these core beliefs that lead to negative self-talk are: "I am worthless", "I am a failure", "I am unlovable".

Positive self-talk (also known as helpful self-talk) involves noticing the reality of the situation, overriding beliefs and biases that can lead to negative self-talk.

Coping self-talk is a particular form of positive self-talk that helps improve performance. It is more effective than generic positive self-talk, and improves engagement in a task. It has three components:

- It acknowledges the emotion the person is feeling.

- It provides some reassurance.

- It is said in non-first person.

An example of coping self-talk is, "John, you're anxious about doing the presentation. Most of the other students are as well. You will be fine."

Coping self-talk is a healthy coping strategy.

Instructional self-talk focuses attention on the components of a task and can improve performance on physical tasks that are being learnt, however it can be detrimental for people who are already skilled in the task.

Relation to Self

Inner speech is strongly associated with a sense of self, and the development of this sense in children is tied to the development of language. There are, however, examples of an internal monologue or inner voice being considered external to the self, such as auditory hallucinations, the conceptualisation of negative or critical thoughts as an inner critic, and as a kind of divine intervention. As a delusion, this can be called "thought insertion".

Though not necessarily external, a conscience is also often thought of as an "inner voice".

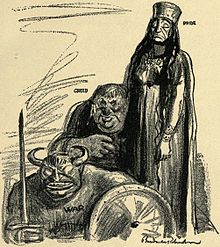

Inner Critic

Inner critic - The ways in which the inner voice acts have been correlated with certain mental conditions such as posttraumatic stress disorder and anxiety. This form of internal monologue may be inherently critical of the person, and even go so far as to feature direct insults or challenges to the individual's behaviour. According to Dr. Lisa Firestone, this "inner critic" is "based on implicit memories of trauma experienced in childhood", and may be the result of both significant traumas (that result in PTSD or other stress disorders) or minor ones.

Personal Pronouns

Intrapersonal communication can be facilitated through both first-person and second-person pronouns. However, through years of research, scholars have already realized that people tend to use first-person and second-person self-talk in different situations. Generally speaking, people are more likely to use the second-person pronoun referring to the self when there is a need for self-regulation, an imperative to overcome difficulties, and facilitation of hard actions whereas first person intrapersonal talks are more frequently used when people are talking to themselves about their feelings.

Recent research also has revealed that using the second-person pronoun to provide self-suggestion is more effective in promoting the intentions to carry out behaviors and performances. The rationale behind this process lies in the idea of classical conditioning, a habit theory which argues that repetition of a stable behavior across consistent contexts can strongly reinforce the association between the specific behavior and the context. Building on such rationale, forming internal conversations using second-person pronouns can naturally reproduce the effect of previous encouragement or positive comments from others, as people have already gotten used to living under second-person instructions and encouragements in their childhood. This self-stimulated encouragement and appraisals from previous experience could also generate positive attitudes, intentions, and behaviors.

Absence of Intrapersonal Communication

According to one study, there is wide variation in how often people report experiencing internal monologue, and some people report very little or none. Younger children are less likely to report using inner speech instead of visual thinking than older children and adults, though it is not known whether this is due to lack of inner speech, or due to insufficiently developed introspection.

Other "inner experiences"

Psychologist Russell Hurlburt divides common self-reported "inner experience" phenomena into five categories. "Inner speaking" can range from a single word to an extended conversation. "Inner seeing" includes visual memories and imaginary visuals. "Feelings", "sensory awareness", and "unsymbolized thinking" also take up large portions of a typical adult's reported inner experiences. Hurlburt has published evidence tentatively suggesting that fMRI scans support the validity of adults' self-reports. People can vary greatly in their inner experiences.

A small minority of people experience aphantasia, a deficit in the ability to visualize, and another minority reports hyperphantasia, which involves extremely vivid imagery.

Criticism

In 1992, a chapter in Communication Yearbook #15, argued that "intrapersonal communication" is a flawed concept. The chapter first itemized the various definitions. Intrapersonal communication, it appears, arises from a series of logical and linguistic improprieties. The descriptor itself, 'intrapersonal communication' is ambiguous: many definitions appear to be circular since they borrow, apply and thereby distort conceptual features (e.g., sender, receiver, message, dialogue) drawn from normal inter-person communication; unknown entities or person-parts allegedly conduct the 'intrapersonal' exchange; in many cases, a very private language is posited which, upon analysis, turns out to be totally inaccessible and ultimately indefensible. In general, intrapersonal communication appears to arise from the tendency to interpret the inner mental processes that precede and accompany our communicative behaviors as if they too were yet another kind of communication process. The overall point is that this reconstruction of our inner mental processes in the language and idioms of everyday public conversation is highly questionable, tenuous at best.

In his later work and especially in the Philosophical Investigations, the philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein (1889–1951) uses a thought experiment to introduce a set of arguments against a hypothetical uniquely constructed "private language", such as intended to be understood only by the author alone. The arguments posit that such a language would be essentially incoherent (even to the author). Even if the author initially believed to understand full well the intended meaning of one's writings at the point of writing, future readings by the author may be fraught with misremembering the meaning intended by one's past self, thus potentially leading to misreading, misinterpretation and misguidedness. Only consensus-based convention provides a relatively stabilizing factor for the continuous maintenance of the flux of linguistic meaning. Language, in this view, is thus restricted to being an inherently social practice.

In Literature

In literary criticism there is a similar term, interior monologue. This, sometimes, is used as a synonym for stream of consciousness: a narrative mode or method that attempts to depict the multitudinous thoughts and feelings which pass through the mind. However, the Oxford Dictionary of Literary Terms suggests that "they can also be distinguished psychologically and literarily. In a psychological sense, stream of consciousness is the subject‐matter, while interior monologue is the technique for presenting it". And for literature, "while an interior monologue always presents a character's thoughts 'directly', without the apparent intervention of a summarizing and selecting narrator, it does not necessarily mingle them with impressions and perceptions, nor does it necessarily violate the norms of grammar, or logic – but the stream of consciousness technique also does one or both of these things".