In mathematics, a complex logarithm is a generalization of the natural logarithm to nonzero complex numbers. The term refers to one of the following, which are strongly related:

- A complex logarithm of a nonzero complex number , defined to be any complex number for which . Such a number is denoted by . If is given in polar form as , where and are real numbers with , then is one logarithm of , and all the complex logarithms of are exactly the numbers of the form for integers . These logarithms are equally spaced along a vertical line in the complex plane.

- A complex-valued function , defined on some subset of the set of nonzero complex numbers, satisfying for all in . Such complex logarithm functions are analogous to the real logarithm function , which is the inverse of the real exponential function and hence satisfies eln x = x for all positive real numbers x. Complex logarithm functions can be constructed by explicit formulas involving real-valued functions, by integration of , or by the process of analytic continuation.

There is no continuous complex logarithm function defined on all of . Ways of dealing with this include branches, the associated Riemann surface, and partial inverses of the complex exponential function. The principal value defines a particular complex logarithm function that is continuous except along the negative real axis; on the complex plane with the negative real numbers and 0 removed, it is the analytic continuation of the (real) natural logarithm.

Problems with inverting the complex exponential function

For a function to have an inverse, it must map distinct values to distinct values; that is, it must be injective. But the complex exponential function is not injective, because for any complex number and integer , since adding to has the effect of rotating counterclockwise radians. So the points

equally spaced along a vertical line, are all mapped to the same number by the exponential function. This means that the exponential function does not have an inverse function in the standard sense. There are two solutions to this problem.

One is to restrict the domain of the exponential function to a region that does not contain any two numbers differing by an integer multiple of : this leads naturally to the definition of branches of , which are certain functions that single out one logarithm of each number in their domains. This is analogous to the definition of on as the inverse of the restriction of to the interval : there are infinitely many real numbers with , but one arbitrarily chooses the one in .

Another way to resolve the indeterminacy is to view the logarithm as a function whose domain is not a region in the complex plane, but a Riemann surface that covers the punctured complex plane in an infinite-to-1 way.

Branches have the advantage that they can be evaluated at complex numbers. On the other hand, the function on the Riemann surface is elegant in that it packages together all branches of the logarithm and does not require an arbitrary choice as part of its definition.

Principal value

Definition

For each nonzero complex number , the principal value is the logarithm whose imaginary part lies in the interval . The expression is left undefined since there is no complex number satisfying .

When the notation appears without any particular logarithm having been specified, it is generally best to assume that the principal value is intended. In particular, this gives a value consistent with the real value of when is a positive real number. The capitalization in the notation is used by some authors to distinguish the principal value from other logarithms of

Calculating the principal value

The polar form of a nonzero complex number is , where is the absolute value of , and is its argument. The absolute value is real and positive. The argument is defined up to addition of an integer multiple of 2π. Its principal value is the value that belongs to the interval , which is expressed as .

This leads to the following formula for the principal value of the complex logarithm:

For example, , and .

The principal value as an inverse function

Another way to describe is as the inverse of a restriction of the complex exponential function, as in the previous section. The horizontal strip consisting of complex numbers such that is an example of a region not containing any two numbers differing by an integer multiple of , so the restriction of the exponential function to has an inverse. In fact, the exponential function maps bijectively to the punctured complex plane , and the inverse of this restriction is . The conformal mapping section below explains the geometric properties of this map in more detail.

The principal value as an analytic continuation

On the region consisting of complex numbers that are not negative real numbers or 0, the function is the analytic continuation of the natural logarithm. The values on the negative real line can be obtained as limits of values at nearby complex numbers with positive imaginary parts.

Properties

Not all identities satisfied by extend to complex numbers. It is true that for all (this is what it means for to be a logarithm of ), but the identity fails for outside the strip . For this reason, one cannot always apply to both sides of an identity to deduce . Also, the identity can fail: the two sides can differ by an integer multiple of ; for instance,

but

The function is discontinuous at each negative real number, but continuous everywhere else in . To explain the discontinuity, consider what happens to as approaches a negative real number . If approaches from above, then approaches which is also the value of itself. But if approaches from below, then approaches So "jumps" by as crosses the negative real axis, and similarly jumps by

Branches of the complex logarithm

Is there a different way to choose a logarithm of each nonzero complex number so as to make a function that is continuous on all of ? The answer is no. To see why, imagine tracking such a logarithm function along the unit circle, by evaluating as increases from to . If is continuous, then so is , but the latter is a difference of two logarithms of so it takes values in the discrete set so it is constant. In particular, , which contradicts .

To obtain a continuous logarithm defined on complex numbers, it is hence necessary to restrict the domain to a smaller subset of the complex plane. Because one of the goals is to be able to differentiate the function, it is reasonable to assume that the function is defined on a neighborhood of each point of its domain; in other words, should be an open set. Also, it is reasonable to assume that is connected, since otherwise the function values on different components of could be unrelated to each other. All this motivates the following definition:

- A branch of is a continuous function defined on a connected open subset of the complex plane such that is a logarithm of for each in .

For example, the principal value defines a branch on the open set where it is continuous, which is the set obtained by removing 0 and all negative real numbers from the complex plane.

Another example: The Mercator series

converges locally uniformly for , so setting defines a branch of on the open disk of radius 1 centered at 1. (Actually, this is just a restriction of , as can be shown by differentiating the difference and comparing values at 1.)

Once a branch is fixed, it may be denoted if no confusion can result. Different branches can give different values for the logarithm of a particular complex number, however, so a branch must be fixed in advance (or else the principal branch must be understood) in order for "" to have a precise unambiguous meaning.

Branch cuts

The argument above involving the unit circle generalizes to show that no branch of exists on an open set containing a closed curve that winds around 0. One says that "" has a branch point at 0". To avoid containing closed curves winding around 0, is typically chosen as the complement of a ray or curve in the complex plane going from 0 (inclusive) to infinity in some direction. In this case, the curve is known as a branch cut. For example, the principal branch has a branch cut along the negative real axis.

If the function is extended to be defined at a point of the branch cut, it will necessarily be discontinuous there; at best it will be continuous "on one side", like at a negative real number.

The derivative of the complex logarithm

Each branch of on an open set is the inverse of a restriction of the exponential function, namely the restriction to the image . Since the exponential function is holomorphic (that is, complex differentiable) with nonvanishing derivative, the complex analogue of the inverse function theorem applies. It shows that is holomorphic on , and for each in . Another way to prove this is to check the Cauchy–Riemann equations in polar coordinates.

Constructing branches via integration

The function for real can be constructed by the formula

In developing the analogue for the complex logarithm, there is an additional complication: the definition of the complex integral requires a choice of path. Fortunately, if the integrand is holomorphic, then the value of the integral is unchanged by deforming the path (while holding the endpoints fixed), and in a simply connected region (a region with "no holes"), any path from to inside can be continuously deformed inside into any other. All this leads to the following:

The complex logarithm as a conformal map

Any holomorphic map satisfying for all is a conformal map, which means that if two curves passing through a point of form an angle (in the sense that the tangent lines to the curves at form an angle ), then the images of the two curves form the same angle at . Since a branch of is holomorphic, and since its derivative is never 0, it defines a conformal map.

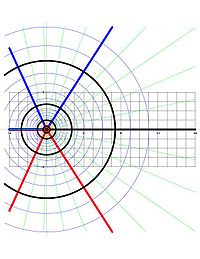

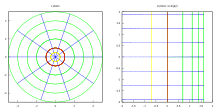

For example, the principal branch , viewed as a mapping from to the horizontal strip defined by , has the following properties, which are direct consequences of the formula in terms of polar form:

- Circles in the z-plane centered at 0 are mapped to vertical segments in the w-plane connecting to , where is the real log of the radius of the circle.

- Rays emanating from 0 in the z-plane are mapped to horizontal lines in the w-plane.

Each circle and ray in the z-plane as above meet at a right angle. Their images under Log are a vertical segment and a horizontal line (respectively) in the w-plane, and these too meet at a right angle. This is an illustration of the conformal property of Log.

The associated Riemann surface

Construction

The various branches of cannot be glued to give a single continuous function because two branches may give different values at a point where both are defined. Compare, for example, the principal branch on with imaginary part in and the branch on whose imaginary part lies in . These agree on the upper half plane, but not on the lower half plane. So it makes sense to glue the domains of these branches only along the copies of the upper half plane. The resulting glued domain is connected, but it has two copies of the lower half plane. Those two copies can be visualized as two levels of a parking garage, and one can get from the level of the lower half plane up to the level of the lower half plane by going radians counterclockwise around 0, first crossing the positive real axis (of the level) into the shared copy of the upper half plane and then crossing the negative real axis (of the level) into the level of the lower half plane.

One can continue by gluing branches with imaginary part in , in , and so on, and in the other direction, branches with imaginary part in , in , and so on. The final result is a connected surface that can be viewed as a spiraling parking garage with infinitely many levels extending both upward and downward. This is the Riemann surface associated to .

A point on can be thought of as a pair where is a possible value of the argument of . In this way, R can be embedded in .

The logarithm function on the Riemann surface

Because the domains of the branches were glued only along open sets where their values agreed, the branches glue to give a single well-defined function . It maps each point on to . This process of extending the original branch by gluing compatible holomorphic functions is known as analytic continuation.

There is a "projection map" from down to that "flattens" the spiral, sending to . For any , if one takes all the points of lying "directly above" and evaluates at all these points, one gets all the logarithms of .

Gluing all branches of log z

Instead of gluing only the branches chosen above, one can start with all branches of , and simultaneously glue every pair of branches and along the largest open subset of on which and agree. This yields the same Riemann surface and function as before. This approach, although slightly harder to visualize, is more natural in that it does not require selecting any particular branches.

If is an open subset of projecting bijectively to its image in , then the restriction of to corresponds to a branch of defined on . Every branch of arises in this way.

The Riemann surface as a universal cover

The projection map realizes as a covering space of . In fact, it is a Galois covering with deck transformation group isomorphic to , generated by the homeomorphism sending to .

As a complex manifold, is biholomorphic with via . (The inverse map sends to .) This shows that is simply connected, so is the universal cover of .

Applications

- The complex logarithm is needed to define exponentiation in which the base is a complex number. Namely, if and are complex numbers with , one can use the principal value to define . One can also replace by other logarithms of to obtain other values of , differing by factors of the form .] The expression has a single value if and only if is an integer.

- Because trigonometric functions can be expressed as rational functions of , the inverse trigonometric functions can be expressed in terms of complex logarithms.

- Since the mapping transforms circles centered at 0 into vertical straight line segments, it is useful in engineering applications involving an annulus.

- In electrical engineering, the propagation constant involves a complex logarithm.

Generalizations

Logarithms to other bases

Just as for real numbers, one can define for complex numbers and

with the only caveat that its value depends on the choice of a branch of log defined at and (with ). For example, using the principal value gives

Logarithms of holomorphic functions

If f is a holomorphic function on a connected open subset of , then a branch of on is a continuous function on such that for all in . Such a function is necessarily holomorphic with for all in .

If is a simply connected open subset of , and is a nowhere-vanishing holomorphic function on , then a branch of defined on can be constructed by choosing a starting point a in , choosing a logarithm of , and defining

for each in .

![{\displaystyle [-1,1]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/51e3b7f14a6f70e614728c583409a0b9a8b9de01)

![{\displaystyle [-\pi /2,\pi /2]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/cd702a5a7041be010f870c0e23750d98ba9919f5)

![{\displaystyle (-\pi ,\pi ]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/7fbb1843079a9df3d3bbcce3249bb2599790de9c)