Parliament of England | |||

|---|---|---|---|

Royal coat of arms of England, 1558–1603 | |||

| Type | |||

| Type | |||

| Houses | Upper house: House of Lords (1341–1649 / 1660–1707) House of Peers (1657–1660) Lower house: House of Commons (1341–1707) | ||

| History | |||

| Established | c. 1236 | ||

| Disbanded | 1 May 1707 | ||

| Preceded by | Curia regis | ||

| Succeeded by | Parliament of Great Britain | ||

| Leadership | |||

William Cowper since 1705 | |||

John Smith since 1705 | |||

| Structure | |||

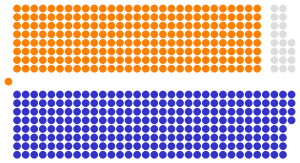

| |||

House of Commons political groups | Final composition of the English House of Commons: 513 Seats Tories: 260 seats Whigs: 233 seats Unclassified: 20 seats | ||

| Elections | |||

| Ennoblement by the Sovereign or inheritance of an English peerage | |||

| First past the post with limited suffrage | |||

| Meeting place | |||

| |||

| Palace of Westminster, Westminster, Middlesex | |||

| Footnotes | |||

| Reflecting Parliament as it stood in 1707.

See also: Parliament of Scotland, Parliament of Ireland | |||

The Parliament of England was the legislature of the Kingdom of England from the 13th century until 1707 when it was replaced by the Parliament of Great Britain. Parliament evolved from the great council of bishops and peers that advised the English monarch. Great councils were first called Parliaments during the reign of Henry III (r. 1216–1272). By this time, the king required Parliament's consent to levy taxation.

Originally a unicameral body, a bicameral Parliament emerged when its membership was divided into the House of Lords and House of Commons, which included knights of the shire and burgesses. During Henry IV's time on the throne, the role of Parliament expanded beyond the determination of taxation policy to include the "redress of grievances", which essentially enabled English citizens to petition the body to address complaints in their local towns and counties. By this time, citizens were given the power to vote to elect their representatives—the burgesses—to the House of Commons.

Over the centuries, the English Parliament progressively limited the power of the English monarchy, a process that arguably culminated in the English Civil War and the High Court of Justice for the trial of Charles I.

Predecessors (pre-13th century)

Since the unification of England in the 10th century, kings had convened national councils of lay magnates and leading churchmen. The Anglo-Saxons called such councils witans. These councils were an important way for kings to maintain ties with powerful men in distant regions of the country. The witan had a role in making and promulgating legislation as well as making decisions concerning war and peace. They were also the venues for state trials, such as the trial of Earl Godwin in 1051.

After the Norman Conquest of 1066, the king received regular council from the members of his curia regis (Latin for "royal court") and periodically enlarged the court by summoning a magnum concilium (Latin for "great council") to discuss national business and promulgate legislation. For example, the Domesday survey was planned at the Christmas council of 1085, and the Constitutions of Clarendon were made at the 1164 council. The magnum concilium continued to be the setting of state trials, such as the trial of Thomas Becket.

The members of the great councils were the king's tenants-in-chief. The greater tenants (archbishops, bishops, abbots, earls, and barons) were summoned by individual writ, but lesser tenants were summoned by sheriffs. These were not representative or democratic assemblies. They were feudal councils in which barons fulfilled their obligation to provide counsel to their lord the king. Councils allowed kings to consult with their leading subjects, but such consultation rarely resulted in a change in royal policy. According to historian Judith Green, "these assemblies were more concerned with ratification and publicity than with debate". In addition, the magnum concilium had no role in approving taxation as the king could levy geld (discontinued after 1162) whenever he wished.

The years between 1189 and 1215 were a time of transition for the great council. The cause of this transition were new financial burdens imposed by the Crown to finance the Third Crusade, ransom Richard I, and pay for the series of Anglo-French wars fought between the Plantagenet and Capetian dynasties. In 1188, a precedent was established when the great council granted Henry II the Saladin tithe. In granting this tax, the great council was acting as representatives for all taxpayers.

The likelihood of resistance to national taxes made consent politically necessary. It was convenient for kings to present the great council as a representative body capable of consenting on behalf of all within the kingdom. Increasingly, the kingdom was described as the communitas regni (Latin for "community of the realm") and the barons as their natural representatives. But this development also created more conflict between kings and the baronage as the latter attempted to defend what they considered the rights belonging to the king's subjects.

King John (r. 1199–1216) alienated the barons by his partiality in dispensing justice, heavy financial demands and abusing his right to feudal incidents, reliefs, and aids. In 1215, the barons forced John to abide by a charter of liberties similar to charters issued by earlier kings . Known as Magna Carta (Latin for "Great Charter"), it was based on three assumptions important to the later development of Parliament:

- the king was subject to the law

- the king could only make law and raise taxation (except customary feudal dues) with the consent of the community of the realm

- that the obedience owed by subjects to the king was conditional and not absolute

Clause 12 stated that certain taxes could only be levied "through the common counsel of our kingdom", and clause 14 specified that this common counsel was to come from bishops, earls, and barons. While the clause stipulating no taxation "without the common counsel" was deleted from later reissues, it was nevertheless adhered to by later kings. Magna Carta would gain the status of fundamental law after John's reign.

13th century

The word parliament comes from the French parlement first used in the late 11th century with the meaning of "parley" or "conversation". In the mid-1230s, it became a common name for meetings of the great council. The word was first used with this meaning in 1236.

In the 13th century, parliaments were developing throughout north-western Europe. As a vassal to the King of France, English kings were suitors to the parlement of Paris. In the 13th century, the French and English parliaments were similar in their functions; however, the two institutions diverged in significant ways in later centuries.

Early meetings

After the 1230s, the normal meeting place for Parliament was fixed at Westminster. Parliaments tended to meet according to the legal year so that the courts were also in session: January or February for the Hilary term, in April or May for the Easter term, in July, and in October for the Michaelmas term.

Most parliaments had between forty and eighty attendees. Meetings of Parliament always included:

- the king

- chief ministers and other ministers (great officers of state, justices of the King's Bench and Common Bench, and barons of the exchequer)

- members of the king's council

- ecclesiastical magnates (archbishops, bishops, abbots, priors)

- lay magnates (earls and barons)

The lower clergy (deans, cathedral priors, archdeacons, parish priests) were occasionally summoned when papal taxation was on the agenda. Beginning around the 1220s, the concept of representation, summarised in the Roman law maxim quod omnes tangit ab omnibus approbetur (Latin for "what touches all should be approved by all"), gained new importance among the clergy, and they began choosing proctors to represent them at church assemblies and, when summoned, at Parliament.

As feudalism declined and the gentry and merchant classes increased in influence, the shires and boroughs were recognised as communes (Latin communitas) with a unified constituency capable of being represented by knights of the shire and burgesses. Initially, knights and burgesses were summoned only when new taxes were proposed so that representatives of the communes (or "the Commons") could report back home that taxes were lawfully granted. The Commons were not regularly summoned until the 1290s, after the so-called "Model Parliament" of 1295. Of the thirty parliaments between 1274 and 1294, knights only attended four and burgesses only two.

Early parliaments increasingly brought together social classes resembling the estates of the realm of continental Europe: the landed aristocracy (barons and knights), the clergy, and the towns. Historian John Maddicott points out that "the main division within parliament was less between lords and commons than between the landed and all others, lower clergy as well as burgesses".

Specialists could be summoned to Parliament to provide expert advice. For example, Roman law experts were summoned from Cambridge and Oxford to the Norham parliament of 1291 to advise on the disputed Scottish succession. At the Bury St Edmunds parliament of 1296, burgesses "who best know how to plan and lay out a certain new town" were summoned to advise on the rebuilding of Berwick after its capture by the English.

Early functions and powers

Parliament—or the "High Court of Parliament" as it became known—was England's highest court of justice. A large amount of its business involved judicial questions referred to it by ministers, judges, and other government officials. Many petitions were submitted to Parliament by individuals whose grievances were not satisfied through normal administrative or judicial channels. As the number of petitions increased, they came to be directed to particular departments (chancery, exchequer, the courts) leaving the king's council to concentrate on the most important business. Parliament became "a delivery point and a sorting house for petitions". From 1290 to 1307, Gilbert of Rothbury was placed in charge of organising parliamentary business and recordkeeping—in effect a clerk of the parliaments.

Kings could legislate outside of Parliament through legislative acta (administrative orders drafted by the king's council as letters patent or letters close) and writs drafted by the chancery in response to particular court cases. But kings could also use Parliament to promulgate legislation. Parliament's legislative role was largely passive—the actual work of law-making was done by the king and council, specifically the judges on the council who drafted statutes. Completed legislation was then presented to Parliament for ratification.

Kings needed Parliament to fund their military campaigns. On the basis of Magna Carta, Parliament asserted for itself the right to consent to taxation, and a pattern developed in which the king would make concessions (such as reaffirming liberties in Magna Carta) in return for tax grants. Withholding taxation was Parliament's main tool in disputes with the king. Nevertheless, the king was still able to raise lesser amounts of revenue from sources that did not require parliamentary consent, such as:

- county farms (the fixed sum paid annually by sheriffs for the privilege of administering and profiting from royal lands in their counties)

- profits from the eyre

- tallage on the royal demesne, the towns, foreign merchants, and most importantly English Jews

- scutage

- feudal dues and fines

- profits from wardship, escheat, and vacant episcopal sees

Henry III

Henry III (r. 1216–1272) became king at nine years old after his father, King John, died during the First Barons' War. During the king's minority, England was ruled by a regency government that relied heavily on great councils to legitimise its actions. Great councils even consented to the appointment of royal ministers, an action that normally was considered a royal prerogative. Historian John Maddicott writes that the "effect of the minority was thus to make the great council an indispensable part of the country's government [and] to give it a degree of independent initiative and authority which central assemblies had never previously possessed".

The regency government officially ended when Henry turned sixteen in 1223, and the magnates demanded the adult king confirm previous grants of Magna Carta made in 1216 and 1217 to ensure their legality. At the same time, the king needed money to defend his possessions in Poitou and Gascony from a French invasion. At a great council in 1225, a deal was reached that saw Magna Carta and the Charter of the Forest reissued in return for taxing a fifteenth (7 percent) of movable property. This set a precedent that taxation was granted in return for the redress of grievances.

Ministers and finances

In 1232, Peter des Roches became the king's chief minister. His nephew, Peter de Rivaux, accumulated a large number of offices, including lord keeper of the privy seal and keeper of the wardrobe; yet, these appointments were not approved by the magnates as had become customary during the regency government. Under Roches, the government revived practices used during King John's reign and that had been condemned in Magna Carta, such as arbitrary disseisins, revoking perpetual rights granted in royal charters, depriving heirs of their inheritances, and marrying heiresses to foreigners.

Both Roches and Rivaux were foreigners from Poitou. The rise of a royal administration controlled by foreigners and dependent solely on the king stirred resentment among the magnates, who felt excluded from power. Several barons rose in rebellion, and the bishops intervened to persuade the king to change ministers. At a great council in April 1234, the king agreed to remove Rivaux and other ministers. This was the first occasion in which a king was forced to change his ministers by a great council or parliament. The struggle between king and Parliament over ministers became a permanent feature of English politics.

Thereafter, the king ruled in concert with an active Parliament, which considered matters related to foreign policy, taxation, justice, administration, and legislation. January 1236 saw the passage of the Statute of Merton, the first English statute. Among other things, the law continued barring bastards from inheritance. Significantly, the language of the preamble describes the legislation as "provided" by the magnates and "conceded" by the king, which implies that this was not simply a royal measure consented to by the barons. In 1237, Henry asked Parliament for a tax to fund his sister Isabella's dowry. The barons were unenthusiastic, but they granted the funds in return for the king's promise to reconfirm Magna Carta, add three magnates to his personal council, limit the royal prerogative of purveyance, and protect land tenure rights.

But Henry was adamant that three concerns were exclusively within his royal prerogative: family and inheritance matters, patronage, and appointments. Important decisions were made without consulting Parliament, such as in 1254 when the king accepted the throne of the Kingdom of Sicily for his younger son, Edmund Crouchback. He also clashed with Parliament over appointments to the three great offices of chancellor, justiciar, and treasurer. The barons believed these three offices should be restraints on royal misgovernment, but the king promoted minor officials within the royal household who owed their loyalty exclusively to him.

In 1253, while fighting in Gascony, Henry requested men and money to resist an anticipated attack from Alfonso X of Castile. In a January 1254 Parliament, the bishops themselves promised an aid but would not commit the rest of the clergy. Likewise, the barons promised to assist the king if he was attacked but would not commit the rest of the laity to pay money. For this reason, the lower clergy of each diocese elected proctors at church synods, and each county elected two knights of the shire. These representatives were summoned to Parliament in April 1254 to consent to taxation. The men elected as shire knights were prominent landholders with experience in local government and as soldiers. They were elected by barons, other knights, and probably freeholders of sufficient standing.

Baronial reform movement

By 1258, the relationship between the king and the baronage had reached a breaking point over the "Sicilian Business", in which Henry had promised to pay papal debts in return for the pope's help securing the Sicilian crown for his son, Edmund. At the Oxford Parliament of 1258, reform-minded barons forced a reluctant king to accept a constitutional framework known as the Provisions of Oxford:

- The king was to govern according to the advice of an elected council of fifteen barons.

- The baronial council appointed royal ministers (justiciar, treasurer, chancellor) to serve for one-year terms.

- Parliament met three times a year on the octave of Michaelmas (October 6), Candlemas (February 3), and June 1.

- The barons elected twelve representatives (two bishops, one earl and nine barons) who together with the baronial council could act on legislation and other matters even when Parliament was not in session as "a kind of standing parliamentary committee".

Parliament now met regularly according to a schedule rather than at the pleasure of the king. The reformers hoped that the provisions would ensure parliamentary approval for all major government acts. Under the provisions, Parliament was "established formally (and no longer merely by custom) as the voice of the community".

The theme of reform dominated later parliaments. During the Michaelmas Parliament of 1258, the Ordinance of Sheriffs was issued as letters patent that forbade sheriffs from taking bribes. At the Candlemas Parliament of 1259, the baronial council and the twelve representatives enacted the Ordinance of the Magnates. In this ordinance, the barons promised to observe Magna Carta and other reforming legislation. They also required their own bailiffs to observe similar rules as those of royal sheriffs, and the justiciar was given power to correct abuses of their officials. The Michaelmas Parliament of 1259 enacted the Provisions of Westminster, a set of legal and administrative reforms designed to address grievances of freeholders and even villeins, such as abuses related to the murdrum fine.

Henry III made his first move against the baronial reformers while in France negotiating peace with Louis IX. Using the excuse of his absence from the realm and Welsh attacks in the marches, Henry ordered the justiciar, Hugh Bigod, to postpone the parliament scheduled for Candlemas 1260. This was an apparent violation of the Provisions of Oxford; however, the provisions were silent on what should happen if the king were outside the kingdom. The king's motive was to prevent the promulgation of further reforms through Parliament. Simon de Montfort, a leader of the baronial reformers, ignored these orders and made plans to hold a parliament in London but was prevented by Bigod. When the king arrived back in England he summoned a parliament which met in July, where Montfort was brought to trial though ultimately cleared of wrongdoing.

In April 1261, the pope released the king from his oath to adhere to the Provisions of Oxford, and Henry publicly renounced the Provisions in May. Most of the barons were willing to let the king reassume power provided he ruled well. By 1262, Henry had regained all of his authority, and Montfort left England. The barons were now divided mainly by age. The elder barons remained loyal to the king, but younger barons coalesced around Montfort, who returned to England in the spring of 1263.

Montfortian parliaments

The royalist barons and rebel barons fought each other in the Second Barons' War. Montfort defeated the king at the Battle of Lewes in 1264 and became the real ruler of England for the next twelve months. Montfort held a parliament in June 1264 to sanction a new form of government and rally support. This parliament was notable for including knights of the shire who were expected to deliberate fully on political matters, not just assent to taxation.

The June Parliament approved a new constitution in which the king's powers were given to a council of nine. The new council was chosen and led by three electors (Montfort, Stephen Bersted, bishop of Chichester, and Gilbert de Clare, earl of Gloucester). The electors could replace any of the nine as they saw fit, but the electors themselves could only be removed by Parliament.

Montfort held two other Parliaments during his time in power. The most famous—Simon de Montfort's Parliament—was held in January 1265 amidst threat of a French invasion and unrest throughout the realm. For the first time, burgesses (elected by those residents of boroughs or towns who held burgage tenure, such as wealthy merchants or craftsmen) were summoned along with knights of the shire.

Montfort was killed at the Battle of Evesham in 1265, and Henry was restored to power. In August 1266, Parliament authorised the Dictum of Kenilworth, which nullified everything Montfort had done and removed all restraints on the king. In 1267, some of the reforms contained in the 1259 Provisions of Westminster were revised in the form of the Statute of Marlborough passed in 1267. This was the start of a process of statutory reform that continued into the reign of Henry's successor.

Edward I

Edward I (r. 1272–1307) learned from the failures of his father's reign the usefulness of Parliament for building consensus and strengthening royal authority. Parliaments were held regularly throughout his reign, generally twice a year at Easter in the spring and after Michaelmas in the autumn.

Under Edward, the first major statutes amending the common law were promulgated in Parliament:

- Statute of Westminster I (1275)

- Statute of Gloucester (1278)

- Statute of Mortmain (1279)

- Statute of Westminster II (1285)

- Statute of Winchester (1285)

- Statute Quia Emptores (1290)

- Statute Quo Warranto (1290)

The first Statute of Westminster required free elections without intimidation. This act was accompanied by the grant of a tax on England's wealthy wool trade—a half-mark (6s 8d) on each sack of wool exported. It became known as the magna et antiqua custuma (Latin: "great and ancient custom") and was granted to Edward and his heirs, becoming part of the Crown's permanent revenue until the 17th century.

Model Parliament

In 1294, the Anglo-French War broke out over control of Gascony. Edward's need for money to finance the war led him to take arbitrary measures. He ordered the seizure of merchants' wool, which was only released after payment of the unpopular maltolt, a tax never authorised by Parliament. Church wealth was arbitrarily seized, and the clergy were further asked to give half of their revenues to the king. They refused but agreed to a smaller sum. Over the next couple years, parliaments approved new taxes, but it was never enough. More money was needed to put down a Welsh rebellion and win the First War of Scottish Independence.

This need for money led to what became known as the "Model Parliament" of November 1295. In addition to magnates who were summoned individually, sheriffs were instructed to send two elected knights from each shire and two elected burgesses from each borough. The Commons had been summoned to earlier parliaments but only with power to consent to what the magnates decided. In the Model Parliament, the writ of summons invested shire knights and burgesses with power to provide both counsel and consent.

Crisis of 1297

By 1296, the King's efforts to recover Gascony were creating resentment among the clergy, merchants, and magnates. At the Bury St Edmunds parliament in 1296, the lay magnates and Commons agreed to pay a tax on moveable property. The clergy refused citing the papal bull Clericis Laicos, which forbade secular rulers from taxing the church without papal permission. In January 1297, a convocation of the clergy met at St Paul's in London to consider the matter further but ultimately could find no way to pay the tax without violating the papal bull. In retaliation, the King outlawed the clergy and confiscated clerical property on 30 January. On 10 February, Robert Winchelsey, archbishop of Canterbury, responded by excommunicating anyone acting against Clericis Laicos. Most clergy paid a fine for the restoration of their property that was identical to the tax requested by the King.

At the Salisbury parliament of March 1297, Edward unveiled his plans for recovering Gascony. The English would mount a two front attack with the King leading an expedition to Flanders while other barons traveled to Gascony. This plan faced opposition from the most important noblemen—Roger Bigod, marshal and earl of Norfolk, and Humphrey Bohun, constable and earl of Hereford. Norfolk and Hereford argued that they owed the king military service in foreign lands but only if the king were present. Therefore, they would not go to Gascony unless the King went as well. Norfolk and Hereford were supported by around 30 barons, and the parliament ended without any decision. After the Salisbury parliament ended, Edward ordered the seizure of wool and payment of a new maltolt.

In July 1297, a writ declared that "the earls, barons, knights, and other laity of our realm" had granted a tax on moveables. In reality, this grant was not made by a parliament but by an informal gathering "standing around in [the king's] chamber". Norfolk and Hereford drew up a list of grievances known as the Remonstrances, which criticized the king's demand for military service and heavy taxes. The maltolt and prises were particularly objectionable due to their arbitrary nature. In August, Bigod and de Bohun arrived at the exchequer protesting that the irregular tax "was never granted by them or the community" and declared they would not pay it.

The outbreak of the First War of Scottish Independence necessitated that both the king and his opponents put aside their differences. At the October 1297 parliament, the council agreed to concessions in the king's absence. In exchange for a new tax, the Confirmatio Cartarum reconfirmed Magna Carta, abolished the maltolt, and formally recognised that "aids, mises, and prises" needed the consent of Parliament.

Later reign

Edward soon broke the agreements of 1297, and his relations with Parliament remained strained for the rest of his reign as he sought further funds for the war in Scotland. At the parliament of March 1300, the king was forced to agree to the Articuli Super Cartas, which gave further concessions to his subjects.

At the Lincoln parliament of 1301, the King heard complaints that the charters were not followed and calls for the dismissal of his chief minister, the treasurer Walter Langton. Demands for appointment of ministers by "common consent" were heard for the first time since Henry III's death. To this, Edward angrily refused, saying that every other magnate in England had the power "to arrange his household, to appoint bailiffs and stewards" without outside interference. He did offer to right any wrongs his officials had committed. Notably, the petition on behalf of "the prelates and leading men of the kingdom acting for the whole community" was presented by Henry de Keighley, knight for Lanchashire. This indicates that knights were holding greater weight in Parliament.

The last four parliaments of Edward's' reign were less contentious. With Scotland nearly conquered, royal finances improved and opposition to royal policies decreased. A number of petitions were considered at the parliament of February 1305 included ones related to crime. In response, Edward issued the trailbaston ordinance. The state trial of Nicholas Seagrave was conducted as part of this parliament as well. Harmonious relations continued between king and Parliament even after December 1305 when Pope Clement V absolved the King of his oath to adhere to Confirmatio Cartarum. The last parliament of the reign was held at Carlisle in 1307. It approved the marriage of the King's son to Isabella of France. Legislation attacking papal provisions and papal taxation was also ratified.

14th century

Edward II (1307–1327)

One of the moments that marked the emergence of parliament as a true institution in England was the deposition of Edward II in January 1327. Even though it is debatable whether Edward II was deposed in parliament or by parliament, this remarkable sequence of events consolidated the importance of parliament in the English unwritten constitution. Parliament was also crucial in establishing the legitimacy of the king who replaced Edward II: his son Edward III.

Edward III (1327–1377)

In 1341 the Commons met separately from the nobility and clergy for the first time, creating what was effectively an Upper Chamber and a Lower Chamber, with the knights and burgesses sitting in the latter. This Upper Chamber became known as the House of Lords from 1544 onward, and the Lower Chamber became known as the House of Commons, collectively known as the Houses of Parliament.

The authority of parliament grew under Edward III; it was established that no law could be made, nor any tax levied, without the consent of both Houses and the Sovereign. This development occurred during the reign of Edward III because he was involved in the Hundred Years' War and needed finances. During his conduct of the war, Edward tried to circumvent parliament as much as possible, which caused this power structure to emerge.

The Commons came to act with increasing boldness during this period. During the Good Parliament of 1376, the Presiding Officer of the lower chamber, Peter de la Mare, complained of heavy taxes, demanded an accounting of the royal expenditures, and criticised the king's management of the military. The Commons even proceeded to impeach some of the king's ministers. The bold Speaker was imprisoned, but was soon released after the death of Edward III.

Richard II (1377–1399)

During the reign of the next monarch, Richard II, the Commons once again began to impeach errant ministers of the Crown. They insisted that they could control not only taxation but also public expenditure. Despite such gains in authority, however, the Commons still remained much less powerful than the House of Lords and the Crown.

15th century

This period saw the introduction of a franchise which limited the number of people who could vote in elections to the House of Commons. From 1430 onwards, the franchise for the election of knights of the shires in the county constituencies was limited to forty-shilling freeholders, meaning men who owned freehold property worth forty shillings (two pounds) or more. The Parliament of England legislated for this new uniform county franchise in the statute 8 Hen. 6. c. 7. The Chronological Table of the Statutes does not mention such a 1430 law, as it was included in the Consolidated Statutes as a recital in the Electors of Knights of the Shire Act 1432 (10 Hen. 6. c. 2), which amended and re-enacted the 1430 law to make clear that the resident of a county had to have a forty shilling freehold in that county to be a voter there.

Tudor era (1485–1603)

During the reign of the Tudor monarchs, it is often argued that the modern structure of the English Parliament began to be created. The Tudor monarchy, according to historian J. E. Neale, was powerful, and there were often periods of several years when parliament did not sit at all. However, the Tudor monarchs realised that they needed parliament to legitimise many of their decisions, mostly out of a need to raise money through taxation legitimately without causing discontent. Thus they consolidated the state of affairs whereby monarchs would call and close parliament as and when they needed it. However, if monarchs did not call Parliament for several years, it is clear the Monarch did not require Parliament except to perhaps strengthen and provide a mandate for their reforms to Religion which had always been a matter within the Crown's prerogative but would require the consent of the Bishopric and Commons.

By the time of the Tudor monarch Henry VII's 1485 coronation, the monarch was not a member of either the Upper Chamber or the Lower Chamber. Consequently, the monarch would have to make his or her feelings known to Parliament through his or her supporters in both houses. Proceedings were regulated by the presiding officer in either chamber.

From the 1540s the presiding officer in the House of Commons became formally known as the "Speaker", having previously been referred to as the "prolocutor" or "parlour" (a semi-official position, often nominated by the monarch, that had existed ever since Peter de Montfort had acted as the presiding officer of the Oxford Parliament of 1258). This was not an enviable job. When the House of Commons was unhappy it was the Speaker who had to deliver this news to the monarch. This began the tradition whereby the Speaker of the House of Commons is dragged to the Speaker's Chair by other members once elected.

A member of either chamber could present a "bill" to parliament. Bills supported by the monarch were often proposed by members of the Privy Council who sat in parliament. For a bill to become law it would have to be approved by a majority of both Houses of Parliament before it passed to the monarch for royal assent or veto. The royal veto was applied several times during the 16th and 17th centuries and it is still the right of the monarch of the United Kingdom and Commonwealth realms to veto legislation today, although it has not been exercised since 1707 (today such an exercise might precipitate some form of constitutional crisis).

When a bill was enacted into law, this process gave it the approval of each estate of the realm: the King, Lords and Commons. The Parliament of England was far from being a democratically representative institution in this period. It was possible to assemble the entire peerage and senior clergy of the realm in one place to form the estate of the Upper Chamber.

The voting franchise for the House of Commons was small; some historians estimate that it was as little as three per cent of the adult male population; and there was no secret ballot. Elections could therefore be controlled by local grandees, because in many boroughs a majority of voters were in some way dependent on a powerful individual, or else could be bought by money or concessions. If these grandees were supporters of the incumbent monarch, this gave the Crown and its ministers considerable influence over the business of parliament.

Many of the men elected to parliament did not relish the prospect of having to act in the interests of others. So a law was enacted, still on the statute book today, whereby it became unlawful for members of the House of Commons to resign their seat unless they were granted a position directly within the patronage of the monarchy (today this latter restriction leads to a legal fiction allowing de facto resignation despite the prohibition, but nevertheless it is a resignation which needs the permission of the Crown). However, while several elections to parliament in this period would be considered corrupt by modern standards, many elections involved genuine contests between rival candidates, even though the ballot was not secret.

Establishment of permanent seat

It was in this period that the Palace of Westminster was established as the seat of the English Parliament. In 1548, the House of Commons was granted a regular meeting place by the Crown, St Stephen's Chapel. This had been a royal chapel. It was made into a debating chamber after Henry VIII became the last monarch to use the Palace of Westminster as a place of residence and after the suppression of the college there.

This room was the home of the House of Commons until it was destroyed by fire in 1834, although the interior was altered several times up until then. The structure of this room was pivotal in the development of the Parliament of England. While most modern legislatures sit in a circular chamber, the benches of the British Houses of Parliament are laid out in the form of choir stalls in a chapel, simply because this is the part of the original room that the members of the House of Commons used when they were granted use of St Stephen's Chapel.

This structure took on a new significance with the emergence of political parties in the late 17th and early 18th centuries, as the tradition began whereby the members of the governing party would sit on the benches to the right of the Speaker and the opposition members on the benches to the left. It is said that the Speaker's chair was placed in front of the chapel's altar. As Members came and went they observed the custom of bowing to the altar and continued to do so, even when it had been taken away, thus then bowing to the Chair, as is still the custom today.

The numbers of the Lords Spiritual diminished under Henry VIII, who commanded the Dissolution of the Monasteries, thereby depriving the abbots and priors of their seats in the Upper House. For the first time, the Lords Temporal were more numerous than the Lords Spiritual. Currently, the Lords Spiritual consist of the Archbishops of Canterbury and York, the Bishops of London, Durham and Winchester, and twenty-one other English diocesan bishops in seniority of appointment to a diocese.

The Laws in Wales Acts of 1535–42 annexed Wales as part of England and this brought Welsh representatives into the Parliament of England, first elected in 1542.

Rebellion and revolution

Parliament had not always submitted to the wishes of the Tudor monarchs. But parliamentary criticism of the monarchy reached new levels in the 17th century. When the last Tudor monarch, Elizabeth I, died in 1603, King James VI of Scotland came to power as King James I, founding the Stuart monarchy.

In 1628, alarmed by the arbitrary exercise of royal power, the House of Commons submitted to Charles I the Petition of Right, demanding the restoration of their liberties. Though he accepted the petition, Charles later dissolved parliament and ruled without them for eleven years. It was only after the financial disaster of the Scottish Bishops' Wars (1639–1640) that he was forced to recall Parliament so that they could authorise new taxes. This resulted in the calling of the assemblies known historically as the Short Parliament of 1640 and the Long Parliament, which sat with several breaks and in various forms between 1640 and 1660.

The Long Parliament was characterised by the growing number of critics of the king who sat in it. The most prominent of these critics in the House of Commons was John Pym. Tensions between the king and his parliament reached a boiling point in January 1642 when Charles entered the House of Commons and tried, unsuccessfully, to arrest Pym and four other members for their alleged treason. The Five Members had been tipped off about this, and by the time Charles came into the chamber with a group of soldiers they had disappeared. Charles was further humiliated when he asked the Speaker, William Lenthall, to give their whereabouts, which Lenthall famously refused to do.

From then on relations between the king and his parliament deteriorated further. When trouble started to brew in Ireland, both Charles and his parliament raised armies to quell the uprisings by native Catholics there. It was not long before it was clear that these forces would end up fighting each other, leading to the English Civil War which began with the Battle of Edgehill in October 1642: those supporting the cause of parliament were called Parliamentarians (or Roundheads), and those in support of the Crown were called Royalists (or Cavaliers).

Battles between Crown and Parliament continued throughout the 17th and 18th centuries, but parliament was no longer subservient to the English monarchy. This change was symbolised in the execution of Charles I in January 1649.

In Pride's Purge of December 1648, the New Model Army (which by then had emerged as the leading force in the parliamentary alliance) purged Parliament of members that did not support them. The remaining "Rump Parliament", as it was later referred to by critics, enacted legislation to put the king on trial for treason. This trial, the outcome of which was a foregone conclusion, led to the execution of the king and the start of an 11-year republic.

The House of Lords was abolished and the purged House of Commons governed England until April 1653, when army chief Oliver Cromwell dissolved it after disagreements over religious policy and how to carry out elections to parliament. Cromwell later convened a parliament of religious radicals in 1653, commonly known as Barebone's Parliament, followed by the unicameral First Protectorate Parliament that sat from September 1654 to January 1655 and the Second Protectorate Parliament that sat in two sessions between 1656 and 1658, the first session was unicameral and the second session was bicameral.

Although it is easy to dismiss the English Republic of 1649–60 as nothing more than a Cromwellian military dictatorship, the events that took place in this decade were hugely important in determining the future of parliament. First, it was during the sitting of the first Rump Parliament that members of the House of Commons became known as "MPs" (Members of Parliament). Second, Cromwell gave a huge degree of freedom to his parliaments, although royalists were barred from sitting in all but a handful of cases.

Cromwell's vision of parliament appears to have been largely based on the example of the Elizabethan parliaments. However, he underestimated the extent to which Elizabeth I and her ministers had directly and indirectly influenced the decision-making process of her parliaments. He was thus always surprised when they became troublesome. He ended up dissolving each parliament that he convened. Yet the structure of the second session of the Second Protectorate Parliament of 1658 was almost identical to the parliamentary structure consolidated in the Glorious Revolution Settlement of 1689.

In 1653 Cromwell had been made head of state with the title Lord Protector of the Realm. The Second Protectorate Parliament offered him the crown. Cromwell rejected this offer, but the governmental structure embodied in the final version of the Humble Petition and Advice was a basis for all future parliaments. It proposed an elected House of Commons as the Lower Chamber, a House of Lords containing peers of the realm as the Upper Chamber. A constitutional monarchy, subservient to parliament and the laws of the nation, would act as the executive arm of the state at the top of the tree, assisted in carrying out their duties by a Privy Council. Oliver Cromwell had thus inadvertently presided over the creation of a basis for the future parliamentary government of England. In 1657 he had the Parliament of Scotland (temporarily) unified with the English Parliament.

In terms of the evolution of parliament as an institution, by far the most important development during the republic was the sitting of the Rump Parliament between 1649 and 1653. This proved that parliament could survive without a monarchy and a House of Lords if it wanted to. Future English monarchs would never forget this. Charles I was the last English monarch ever to enter the House of Commons.

Even to this day, a Member of the Parliament of the United Kingdom is sent to Buckingham Palace as a ceremonial hostage during the State Opening of Parliament, in order to ensure the safe return of the sovereign from a potentially hostile parliament. During the ceremony the monarch sits on the throne in the House of Lords and signals for the Lord Great Chamberlain to summon the House of Commons to the Lords Chamber. The Lord Great Chamberlain then raises his wand of office to signal to the Gentleman Usher of the Black Rod, who has been waiting in the central lobby. Black Rod turns and, escorted by the doorkeeper of the House of Lords and an inspector of police, approaches the doors to the chamber of the Commons. The doors are slammed in his face—symbolising the right of the Commons to debate without the presence of the monarch's representative. He then strikes three times with his staff (the Black Rod), and he is admitted.

Parliament from the Restoration to the Act of Settlement

The revolutionary events that occurred between 1620 and 1689 all took place in the name of Parliament. The new status of Parliament as the central governmental organ of the English state was consolidated during the events surrounding the Restoration of the monarchy in 1660.

After the death of Oliver Cromwell in September 1658, his son Richard Cromwell succeeded him as Lord Protector, summoning the Third Protectorate Parliament in the process. When this parliament was dissolved under pressure from the army in April 1659, the Rump Parliament was recalled at the insistence of the surviving army grandees. This in turn was dissolved in a coup led by army general John Lambert, leading to the formation of the Committee of Safety, dominated by Lambert and his supporters.

When the breakaway forces of George Monck invaded England from Scotland, where they had been stationed without Lambert's supporters putting up a fight, Monck temporarily recalled the Rump Parliament and reversed Pride's Purge by recalling the entirety of the Long Parliament. They then voted to dissolve themselves and call new elections, which were arguably the most democratic for 20 years although the franchise was still very small. This led to the calling of the Convention Parliament which was dominated by royalists. This parliament voted to reinstate the monarchy and the House of Lords. Charles II returned to England as king in May 1660. The Anglo-Scottish parliamentary union that Cromwell had established was dissolved in 1661 when the Scottish Parliament resumed its separate meeting place in Edinburgh.

The Restoration began the tradition whereby all governments looked to parliament for legitimacy. In 1681 Charles II dissolved parliament and ruled without them for the last four years of his reign. This followed bitter disagreements between the king and parliament that had occurred between 1679 and 1681. Charles took a big gamble by doing this. He risked the possibility of a military showdown akin to that of 1642. However, he rightly predicted that the nation did not want another civil war. Parliament disbanded without a fight. Events that followed ensured that this would be nothing but a temporary blip.

Charles II died in 1685 and he was succeeded by his brother James II. During his lifetime Charles had always pledged loyalty to the Protestant Church of England, despite his private Catholic sympathies. James was openly Catholic. He attempted to lift restrictions on Catholics taking up public offices. This was bitterly opposed by Protestants in his kingdom. They invited William of Orange, a Protestant who had married Mary, daughter of James II and Anne Hyde to invade England and claim the throne.

William assembled an army estimated at 15,000 soldiers (11,000 foot and 4000 horse) and landed at Brixham in southwest England in November, 1688. When many Protestant officers, including James's close adviser, John Churchill, 1st Duke of Marlborough, defected from the English army to William's invasion force, James fled the country. Parliament then offered the Crown to his Protestant daughter Mary, instead of his infant son (James Francis Edward Stuart), who was baptised Catholic. Mary refused the offer, and instead William and Mary ruled jointly, with both having the right to rule alone on the other's death.

As part of the compromise in allowing William to be King—called the Glorious Revolution—Parliament was able to have the 1689 Bill of Rights enacted. Later the 1701 Act of Settlement was approved. These were statutes that lawfully upheld the prominence of parliament for the first time in English history. These events marked the beginning of the English constitutional monarchy and its role as one of the three elements of parliament.

Union: the Parliament of Great Britain

After the Treaty of Union in 1707, acts of Parliament passed in both the Parliament of England and the Parliament of Scotland created a new Kingdom of Great Britain and dissolved both parliaments, replacing them with a new Parliament of Great Britain based in the former home of the English parliament. The Parliament of Great Britain later became the Parliament of the United Kingdom in 1801 when the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland was formed through the Acts of Union 1800.

Acts of Parliament

Specific acts of Parliament can be found at the following articles:

- List of acts of the Parliament of England

- List of ordinances and acts of the Parliament of England, 1642–1660

Locations

Other than London, Parliament was also held in the following cities:

- York, various

- Lincoln, various

- Oxford, 1258 (Mad Parliament), 1681

- Kenilworth, 1266

- Acton Burnell Castle, 1283

- Shrewsbury, 1283 (trial of Dafydd ap Gruffydd), 1397 ('Great' Parliament)

- Carlisle, 1307

- Oswestry Castle, 1398

- Northampton 1328

- New Sarum (Salisbury), 1330

- Winchester, 1332, 1449

- Leicester, 1414 (Fire and Faggot Parliament), 1426 (Parliament of Bats)

- Reading Abbey, 1453

- Coventry, 1459 (Parliament of Devils)