In physics, optical depth or optical thickness is the natural logarithm of the ratio of incident to transmitted radiant power through a material. Thus, the larger the optical depth, the smaller the amount of transmitted radiant power through the material. Spectral optical depth or spectral optical thickness is the natural logarithm of the ratio of incident to transmitted spectral radiant power through a material. Optical depth is dimensionless, and in particular is not a length, though it is a monotonically increasing function of optical path length, and approaches zero as the path length approaches zero. The use of the term "optical density" for optical depth is discouraged.

In chemistry, a closely related quantity called "absorbance" or "decadic absorbance" is used instead of optical depth: the common logarithm of the ratio of incident to transmitted radiant power through a material. It is the optical depth divided by loge(10), because of the different logarithm bases used.

Mathematical definitions

Optical depth

Optical depth of a material, denoted , is given by:where

- is the radiant flux received by that material;

- is the radiant flux transmitted by that material;

- is the transmittance of that material.

The absorbance is related to optical depth by:

Spectral optical depth

Spectral optical depth in frequency and spectral optical depth in wavelength of a material, denoted and respectively, are given by: where

- is the spectral radiant flux in frequency transmitted by that material;

- is the spectral radiant flux in frequency received by that material;

- is the spectral transmittance in frequency of that material;

- is the spectral radiant flux in wavelength transmitted by that material;

- is the spectral radiant flux in wavelength received by that material;

- is the spectral transmittance in wavelength of that material.

Spectral absorbance is related to spectral optical depth by: where

- is the spectral absorbance in frequency;

- is the spectral absorbance in wavelength.

Relationship with attenuation

Attenuation

Optical depth measures the attenuation of the transmitted radiant power in a material. Attenuation can be caused by absorption, but also reflection, scattering, and other physical processes. Optical depth of a material is approximately equal to its attenuation when both the absorbance is much less than 1 and the emittance of that material (not to be confused with radiant exitance or emissivity) is much less than the optical depth: where

- Φet is the radiant power transmitted by that material;

- Φeatt is the radiant power attenuated by that material;

- Φei is the radiant power received by that material;

- Φee is the radiant power emitted by that material;

- T = Φet/Φei is the transmittance of that material;

- ATT = Φeatt/Φei is the attenuation of that material;

- E = Φee/Φei is the emittance of that material,

and according to the Beer–Lambert law, so:

Attenuation coefficient

Optical depth of a material is also related to its attenuation coefficient by:where

- l is the thickness of that material through which the light travels;

- α(z) is the attenuation coefficient or Napierian attenuation coefficient of that material at z,

and if α(z) is uniform along the path, the attenuation is said to be a linear attenuation and the relation becomes:

Sometimes the relation is given using the attenuation cross section of the material, that is its attenuation coefficient divided by its number density: where

- σ is the attenuation cross section of that material;

- n(z) is the number density of that material at z,

and if is uniform along the path, i.e., , the relation becomes:

Applications

Atomic physics

In atomic physics, the spectral optical depth of a cloud of atoms can be calculated from the quantum-mechanical properties of the atoms. It is given bywhere

- d is the transition dipole moment;

- n is the number of atoms;

- ν is the frequency of the beam;

- c is the speed of light;

- ħ is the reduced Planck constant;

- ε0 is the vacuum permittivity;

- σ is the cross section of the beam;

- γ is the natural linewidth of the transition.

Atmospheric sciences

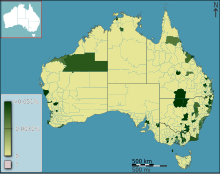

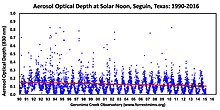

In atmospheric sciences, one often refers to the optical depth of the atmosphere as corresponding to the vertical path from Earth's surface to outer space; at other times the optical path is from the observer's altitude to outer space. The optical depth for a slant path is τ = mτ′, where τ′ refers to a vertical path, m is called the relative airmass, and for a plane-parallel atmosphere it is determined as m = sec θ where θ is the zenith angle corresponding to the given path. Therefore,The optical depth of the atmosphere can be divided into several components, ascribed to Rayleigh scattering, aerosols, and gaseous absorption. The optical depth of the atmosphere can be measured with a Sun photometer.

The optical depth with respect to the height within the atmosphere is given by and it follows that the total atmospheric optical depth is given by

In both equations:

- ka is the absorption coefficient

- w1 is the mixing ratio

- ρ0 is the density of air at sea level

- H is the scale height of the atmosphere

- z is the height in question

The optical depth of a plane parallel cloud layer is given by where:

- Qe is the extinction efficiency

- L is the liquid water path

- H is the geometrical thickness

- N is the concentration of droplets

- ρl is the density of liquid water

So, with a fixed depth and total liquid water path, .

Astronomy

In astronomy, the photosphere of a star is defined as the surface where its optical depth is 2/3. This means that each photon emitted at the photosphere suffers an average of less than one scattering before it reaches the observer. At the temperature at optical depth 2/3, the energy emitted by the star (the original derivation is for the Sun) matches the observed total energy emitted.

Note that the optical depth of a given medium will be different for different colors (wavelengths) of light.

For planetary rings, the optical depth is the (negative logarithm of the) proportion of light blocked by the ring when it lies between the source and the observer. This is usually obtained by observation of stellar occultations.

![{\displaystyle \tau =Q_{\text{e}}\left[{\frac {9\pi L^{2}HN}{16\rho _{l}^{2}}}\right]^{1/3}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/e6bb6a395807fba5896c1bc51055909ca3375b43)