| |

| Long title | An Act to provide for an exchange of lands with the Indians residing in any of the states or territories, and for their removal west of the river Mississippi. |

|---|---|

| Enacted by | the 21st United States Congress |

| Citations | |

| Public law | Pub. L. 21–148 |

| Statutes at Large | 4 Stat. 411 |

| Legislative history | |

| |

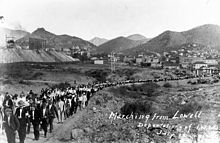

The Indian Removal Act was signed into law on May 28, 1830, by United States President Andrew Jackson. The law, as described by Congress, provided "for an exchange of lands with the Indians residing in any of the states or territories, and for their removal west of the river Mississippi." During the Presidency of Jackson (1829-1837) and his successor Martin Van Buren (1837-1841) more than 60,000 Indians from at least 18 tribes were forced to move west of the Mississippi River where they were allocated new lands. The southern tribes were resettled mostly in Indian Territory (Oklahoma). The northern tribes were resettled initially in Kansas. With a few exceptions the United States east of the Mississippi and south of the Great Lakes was emptied of its Indian population. The movement westward of the Indian tribes was characterized by a large number of deaths occasioned by the hardships of the journey.

The U.S. Congress approved the Act by a narrow majority in the House of Representatives. The Indian Removal Act was supported by President Jackson, southern and white settlers, and several state governments, especially that of Georgia. Indian tribes, the Whig Party, and many Americans opposed the bill. Legal efforts to allow Indian tribes to remain on their land in the eastern U.S. failed. Most famously, the Cherokee (excluding the Treaty Party) challenged their relocation, but were unsuccessful in the courts; they were forcibly removed by the United States government in a march to the west that later became known as the Trail of Tears.

Background

Cultural assimilation

When Europeans and Native Americans came into contact during colonial times or in the early United States, the Europeans felt their civilization to be superior: they were Christians, and they believed their notions of private property to be a superior system of land tenure. European encroachers inflicted a practice of cultural assimilation, meaning that Cherokee peoples were forced to adopt aspects of European civilization. This acculturation was originally proposed by George Washington and was well underway among the Cherokee and the Choctaw by the beginning of the 19th century. Native peoples were encouraged to adopt European customs. First, they were forced to convert to Christianity and abandon traditional religious practices. They were also required to learn to speak and read English, although there was interest in creating a writing and printing system for a few Native languages, especially Cherokee, exemplified by Sequoyah's Cherokee syllabary. The Native Americans also had to adopt settler values, such as monogamous heterosexual marriage and abandon non-marital sex. Finally, they had to accept the concept of individual ownership of land and other property (including, in some instances, African people as slaves). Many Cherokee people adopted all, or some, of these practices, including Cherokee chief John Ross, John Ridge, and Elias Boudinot, as represented by the newspaper he edited, The Cherokee Phoenix.

The perceived failure of the policy

The United States government began a systematic effort to remove Native peoples from the Southeast. The Chickasaw, Choctaw, Muscogee-Creek, Seminole, and original Cherokee nations had been established as autonomous nations in the southeastern United States.

Andrew Jackson sought to renew a policy of political and military action for the removal of the Natives from these lands and worked toward enacting a law for "Indian removal". In his 1829 State of the Union address, Jackson called for Indian removal.

The Indian Removal Act was put in place to annex Native land and then transfer that ownership to Southern states, especially Georgia. The Act was passed in 1830, although dialogue had been ongoing since 1802 between Georgia and the federal government concerning the possibility of such an act. Ethan Davis states that "the federal government had promised Georgia that it would extinguish Indian title within the state's borders by purchase 'as soon as such purchase could be made upon reasonable terms'". As time passed, Southern states began to speed up the expulsions by claiming that the deal between Georgia and the federal government was invalid and that Southern states could pass laws extinguishing Indian title themselves. In response, the federal government passed the Indian Removal Act on May 28, 1830, in which President Jackson agreed to divide the United States territory west of the Mississippi River into districts for tribes to replace the land from which they were removed.

In the 1823 case of Johnson v. M'Intosh, the United States Supreme Court handed down a decision stating that Indians could occupy and control lands within the United States but could not hold title to those lands. Jackson viewed the union as a federation of highly esteemed states, as was common before the American Civil War. He opposed Washington's policy of establishing treaties with Indian tribes as if they were sovereign foreign nations. Thus, the creation of Indian jurisdictions was a violation of state sovereignty under Article IV, Section 3 of the Constitution. As Jackson saw it, either Indians comprised sovereign states (which violated the Constitution) or they were subject to the laws of existing states of the Union. Jackson urged Indians to assimilate and obey state laws. Further, he believed that he could only accommodate the desire for Native self-rule in federal territories, which required resettlement on Federal lands west of the Mississippi River.

Support and opposition

The Removal Act was strongly supported in the South, especially in Georgia, which was the largest state in 1802 and was involved in a jurisdictional dispute with the Cherokee. President Jackson hoped that removal would resolve the Georgia crisis. Besides the Five Civilized Tribes, additional people affected included the Wyandot, the Kickapoo, the Potowatomi, the Shawnee, and the Lenape.

The Indian Removal Act was controversial. Many Americans during this time favored its passage, but there was also significant opposition. Many Christian missionaries protested against it, most notably missionary organizer Jeremiah Evarts. In Congress, New Jersey Senator Theodore Frelinghuysen, Kentucky Senator Henry Clay, Tennessee Congressman Davy Crockett spoke out against the legislation. The Removal Act passed only after a bitter debate in Congress. Clay extensively campaigned against it on the National Republican Party ticket in the 1832 United States presidential election.

Jackson viewed the demise of Native nations as inevitable, pointing to the steady expansion of European-based lifestyle and the decimation of Native nations in the U.S.'s northeast region. He called his Northern critics hypocrites, given the North's history regarding Natives nations within their claimed territory. Jackson stated that "progress requires moving forward."

Humanity has often wept over the fate of the aborigines of this country and philanthropy has long been busily employed in devising means to avert it, but its progress has never for a moment been arrested, and one by one have many powerful tribes disappeared from the earth... But true philanthropy reconciles the mind to these vicissitudes as it does to the extinction of one generation to make room for another... In the monuments and fortresses of an unknown people, spread over the extensive regions of the West, we behold the memorials of a once powerful race, which was exterminated or has disappeared to make room for the existing savage tribes… Philanthropy could not wish to see this continent restored to the condition in which it was found by our forefathers. What good man would prefer a country covered with forests and ranged by a few thousand savages to our extensive Republic, studded with cities, towns, and prosperous farms, embellished with all the improvements which art can devise or industry execute, occupied by more than 12,000,000 happy people, and filled with all the blessings of liberty, civilization, and religion?

According to historian H. W. Brands, Jackson sincerely believed that his population transfer was a "wise and humane policy" that would save the Native Americans from "utter annihilation". Jackson portrayed the removal as a generous act of mercy.

According to Robert M. Keeton, proponents of the bill used biblical narratives to justify the forced resettlement of Native Americans.

Vote

On April 24, 1830, the Senate passed the Indian Removal Act by a vote of 28 to 19. On May 26, 1830, the House of Representatives passed the Act by a vote of 101 to 97. On May 28, 1830, the Indian Removal Act was signed into law by President Andrew Jackson.

Implementation

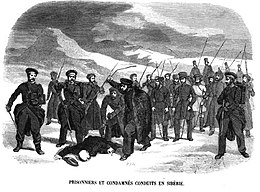

The Removal Act paved the way for the forced expulsion of tens of thousands of American Indians from their land into the West in an event widely known as the "Trail of Tears," a forced resettlement of the Indian population. The first removal treaty signed was the Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek on September 27, 1830, in which Choctaws in Mississippi ceded land east of the river in exchange for payment and land in the West. The Treaty of New Echota was signed in 1835 and resulted in the removal of the Cherokee on the Trail of Tears.

The Seminoles and other tribes did not leave peacefully, as they resisted the removal along with fugitive slaves. The Second Seminole War lasted from 1835 to 1842 and resulted in the government allowing them to remain in south Florida swampland. Only a small number remained, and around 3,000 were removed in the war.