From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

The

racial achievement gap in the United States refers to disparities in educational achievement between differing ethnic/racial groups.

It manifests itself in a variety of ways: African-American and Hispanic

students are more likely to earn lower grades, score lower on

standardized tests,

drop out of high school, and they are less likely to enter and complete college than whites, while whites score lower than Asian Americans.

There is disagreement among scholars regarding the causes of the

racial achievement gap. Some focus on the home life of individual

students, and others focus more on unequal access to resources between

certain ethnic groups. Additionally, political histories, such as anti-literacy laws,

and current policies, such as those related to school funding, have

resulted in an education debt between districts, schools, and students.

The achievement gap affects economic disparities, political participation, and political representation. Solutions have ranged from national policies such as No Child Left Behind and the Every Student Succeeds Act, to private industry closing this gap, and even local efforts.

Overview

Over the past 45 years, students in the United States have made

notable gains in academic achievement. However, racial achievement gaps

remain because not all groups of students are advancing at the same

rates. Evidence of the racial achievement gaps have been manifested

through standardized test scores, high school dropout rates, high school

completion rates, college acceptance and retention rates, as well as

through longitudinal trends. While efforts to close racial achievement

gaps have increased over the years with varying success, studies have

shown that disparities still exist between achievement levels of

differing ethnic groups.

Early schooling years

Racial achievement gaps have been found to exist before students enter kindergarten for their first year of schooling, as a "school readiness" gap.

One study claims that about half the test score gap between black and

white high school students is already evident when children start

school.

Children of Latino, Native, and African American heritage arrive to

kindergarten and first grade with lower levels of oral language,

reading, and mathematics skill than Caucasian and Asian American

children.

While results differ depending on the instrument, estimates of the

black-white gap range from slightly less than half a standard deviation

to slightly more than 1 standard deviation.

Reardon and Galindo (2009), using data from the ECLS-K, found that

average Hispanic and black students begin kindergarten with math scores

three quarters of a standard deviation lower than those of white

students and with reading scores a half standard deviation lower than

those of white students. Six years later, Hispanic-white gaps narrow by

roughly a third, whereas black-white gaps widen by about a third. More

specifically, the Hispanic-white gap is a half standard deviation in

math, and three-eighths in reading at the end of fifth grade. The trends

in the Hispanic-white gaps are especially interesting because of the

rapid narrowing that occurs between kindergarten and first grade.

Specifically, the estimated math gap declines from 0.77 to 0.56 standard

deviations, and the estimated reading gap from 0.52 to 0.29 in the

roughly 18 months between the fall of kindergarten and the spring of

first grade. In the four years from the spring of first grade through

the spring of fifth grade, the Hispanic-white gaps narrow slightly to

0.50 standard deviations in math and widening slightly to 0.38

deviations in reading.

In a 2009 study Clotfelter et al. examine test scores of North Carolina public school students by race.

They found that while black-white gaps are substantial, both Hispanic

and Asian students tend to gain on whites as they progress in school.

The white-black achievement gap in both math and reading scores is

around half a standard deviation. By fifth grade, Hispanic and white

students have roughly the same math and reading scores. By eighth grade,

scores for Hispanic students in North Carolina surpassed those of

observationally equivalent whites by roughly a tenth of a standard

deviation. Asian students surpass whites on math and reading tests in

all years except third and fourth grade reading.

In both fourth-grade reading and eighth-grade math, African American

students are about two and a half times as likely as white students to

lack basic skills and only about one-third as likely to be proficient or

advanced.

In a 2006 study, LoGerfo, Nichols, and Reardon (2006) found that,

starting in the eighth grade, white students have an initial advantage

in reading achievement over black and Hispanic students but not Asian

students. Using nationally representative data from by the National Center for Education Statistics

(NCES)—the Early Childhood Longitudinal Study (ECLS-K) and the National

Education Longitudinal Study (NELS:88), LoGerfo, Nichols, and Reardon

(2006) find that black students score 5.49 points lower than white

students and Hispanic students score 4.83 points lower than white

students on reading tests. These differences in initial status are

compounded by differences in reading gains made during high school.

Specifically, between ninth and tenth grades, white students gain

slightly more than black students and Hispanic students, but white

students gain less than Asian students. Between tenth and twelfth

grades, white students gain at a slightly faster rate than black

students, but white students gain at a slower rate than Hispanic

students and Asian students.

In eighth grade, white students also have an initial advantage over black and Hispanic students in math tests.

However, Asian students have an initial 2.71 point advantage over white

students and keep pace with white students throughout high school.

Between eighth and tenth grade, black students and Hispanic students

make slower gains in math than white students, and black students fall

farthest behind. Asian students gain 2.71 points more than white

students between eight and tenth grade. Some of these differences in

gains persist later in high school. For example, between tenth and

twelfth grades, white students gain more than black students, and Asian

students gain more than white students. There are no significant

differences in math gains between white students and Hispanic students.

By the end of high school, gaps between groups increase slightly.

Specifically, the initial 9-point advantage of white students over black

students increases by about a point, and the initial advantage of Asian

students over white students also increases by about a point.

Essentially, by the end of high school, Asian students are beginning to

learn intermediate-level math concepts, whereas black and Hispanic

students are far behind, learning fractions and decimals, which are math

concepts that the white and Asian students learned in the eighth grade.

Black and Hispanic students end twelfth grade with scores 11 and 7

points behind those of white students, while the male-female difference

in math scores is only around 2 points.

Standardized test scores

The racial group differences across admissions tests, such as the SAT, ACT, GRE, GMAT, MCAT, LSAT, Advanced Placement Program

examinations and other measures of educational achievement, have been

fairly consistent. Since the 1960s, the population of students taking

these assessments has become increasingly diverse. Consequently, the

examination of ethnic score differences has been more rigorous.

Specifically, from six large surveys conducted between 1965 and 1992,

the largest gap exists between white and African American students. On

average, they score about .82 to 1.18 standard deviations lower than

white students in composite test scores.

Following closely behind is the gap between white and Hispanic

students. The overall performance of Asian American students was higher

than that of white students, except Asian American students performed

one quarter standard deviation unit lower on the SAT verbal section, and

about one half a standard deviation unit higher in the GRE Quantitative

test.

However, in the current version of the SAT, Asian-American students of Taiwanese, Korean, Japanese, Indian and Han Chinese

descent have scored higher on both the verbal and math sections of the

new SAT test than whites and all other student racial groups.

The National Assessment of Educational Progress reports the

national Black-White gap and the Hispanic-White Gap in math and reading

assessments, measured at the 4th and 8th grade level. The trends show

that both gaps widen in mathematics as students grow older, but tend to

stay the same in reading. Furthermore, the NAEP measures the widening

and narrowing of achievement gaps on a state level. From 2007 to 2009,

the achievement gaps for the majority of states stayed the same,

although more fluctuations were seen at the 8th grade level than the 4th

grade level.

The Black-White Gap demonstrates:

- In mathematics, a 26-point difference at the 4th grade level and a 31-point difference at the 8th grade level.

- In reading, a 27-point difference at the 4th grade level and a 26-point difference at the 8th grade level.

The Hispanic White Gap demonstrates:

- In mathematics, a 21-point difference at the 4th grade level and a 26-point difference at the 8th grade level.

- In reading, there is a 25-point difference at the 4th grade level and a 24-point difference at the 8th grade level (NAEP, 2011).

The National Educational Longitudinal Survey (NELS, 1988)

demonstrates similar findings in their evaluation of assessments

administered to 12th graders in reading and math.

Mathematics

Results of the mathematics achievement test:

White-African American gap

Non Hispanic White-Hispanic gap

Reading

Results of the reading achievement test:

White-African American gap

Non Hispanic White-Hispanic gap

SAT scores

Racial

and ethnic variations in SAT scores follow a similar pattern to other

racial achievement gaps. In 1990, the average SAT was 528 for Asian-Americans, 491 for whites, 429 for Mexican Americans and 385 for blacks.

34% of Asians compared with 20% of whites, 3% of blacks, 7% of Mexican

Americans, and 9% of Native Americans scored above a 600 on the SAT math

section.

On the SAT verbal section in 1990, whites scored an average of 442,

compared with 410 for Asians, 352 for blacks, 380 for Mexican Americans,

and 388 for Native Americans.

In 2015, the average SAT scores on the math section were 598 for

Asian-Americans, 534 for whites, 457 for Hispanic Latinos and 428 for blacks.

Additionally, 10% of Asian-Americans, 8% of whites, 3% of Mexican

Americans, 3% of Native Americans and 2% of blacks scored above 600 on

the SAT verbal section in 1990.

Race gaps on the SATs are especially pronounced at the tails of the

distribution. In a perfectly equal distribution, the racial breakdown of

scores at every point in the distribution should ideally mirror the

demographic composition of test-takers as whole i.e. 51% whites, 21%

Hispanic Latinos, 14% blacks, and 14% Asian-Americans. But ironically,

among the highest top scorers, those scoring between a 750 and 800

(perfect scores) over 60% are East Asians of Taiwanese, Japanese, Korean and Han Chinese descent, while only 33% are white, compared to 5% Hispanic Latinos and 2% blacks.

There are some limitations to the data which may mean that, if

anything, the race gap is being understated. The ceiling on the SAT

score may, for example, understate the achievement and full potential of

East Asians of Taiwanese, Japanese, Korean and Han Chinese descent. If

the exam was redesigned to increase score variance (add harder and

easier questions than it currently has), the achievement gap across

racial groups could be even more wider and pronounced. In other words,

if the math section was scored between 0 and 1000, we might see more

complete tails on both the right and the left. More East Asians score

between 750 and 800 than score between 700 and 750, suggesting that many

East Asians of Taiwanese, Japanese, Korean and Han Chinese descent

could be scoring high above 800 if the test allowed them to.

State standards tests

Most

state tests showing African American failure rates anywhere from two to

four times the rate of whites, such as Washington State's WASL

test, and only half to one-quarter as likely to achieve a high score,

even though these tests were designed to eliminate the negative effects

of bias associated with standardized multiple choice tests. It is a top

goal of education reform to eliminate the Education gap between all races, though skeptics question whether legislation such as No Child Left Behind truly closes the gap just by raising expectations. Others, such as Alfie Kohn, observe it may merely penalize those who do not score as well as the most educated ethnic and income groups.

Scored Level 3 on WASL Washington Assessment of Student Learning, Mathematics Grade 4 (1997) Data: Office Washington State Superintendent of Instruction

| White

|

Black

|

Hispanic

|

Asian

|

Native American

|

| 17.1%

|

4.0%

|

4.3%

|

15.6%

|

1.6%

|

Education attainment

High school

In 2017, 93% of all 18- through 24-year-olds not enrolled in elementary or secondary school had completed high school.

The gap between black and white completion rates narrowed since the

1970s, with completion rates for white students increasing from 86% in

1972 to 95% in 2017, and completion rates for black students rising from

72% in 1972 to 94% in 2017.

High school completion rates by race, 2017

| Asian/Pacific Islander

|

98.6%

|

| White

|

94.8%

|

| Black

|

93.8%

|

| Hispanic

|

88.3%

|

High school dropout rates by race, 2017

| Asian

|

2.1%

|

| White

|

4.3%

|

| Black

|

6.5%

|

| Hispanic

|

8.2%

|

Post-secondary education

As

of 2008, 13 percent of Hispanics adults have earned a bachelor's degree

or higher, compared with 15 percent of American Indian/Alaska Native

adults, 20 percent of blacks, 33 percent of whites, and 52 percent of

Asian Americans. Asians obtain more first professional degrees than any other race. The table below shows the number of degrees awarded for each group.

Post-secondary degree attainment by race, 2008

| Race |

Associate degree |

Bachelor's degree |

Master's degree |

First professional degree |

Cumulative %

|

| Asians

|

6.9%

|

31.6%

|

14.0%

|

6.4%

|

58.9%

|

| Whites

|

9.3%

|

21.1%

|

8.4%

|

3.1%

|

41.9%

|

| Blacks

|

8.9%

|

13.6%

|

4.9%

|

1.3%

|

28.7%

|

| American Indians/Alaska Natives

|

8.4%

|

9.8%

|

3.6%

|

1.4%

|

23.2%

|

| Hispanics

|

6.1%

|

9.4%

|

2.9%

|

1.0%

|

19.4%

|

(Issued August 2003) Educational attainment by race and gender: 2000

Census 2000 Brief

Percent of Adults 25 and over in group

Ranked by advanced degree HS SC BA AD

Asian alone . .. . . . . . . . . . . . . . 80.4 64.6 44.1 17.4

White alone, not Hispanic or Latino.. . . . 85.5 55.4 27.0 9.8

White alone... . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 83.6 54.1 26.1 9.5

Two or more races. . . . . . . . . . . . 73.3 48.1 19.6 7.0

Black or African American alone . . . . . 72.3 42.5 14.3 4.8

Native Hawaiian and Other Pacific Islander 78.3 44.6 13.8 4.1

American Indian and Alaska Native alone . . 70.9 41.7 11.5 3.9

Hispanic or Latino (of any race).. . . . . 52.4 30.3 10.4 3.8

Some other race alone . . . . . . . . . . . 46.8 25.0 7.3 2.3

HS = high school completed SC = some college

BA = bachelor's degree AD = advanced degree

In 2018, the overall college enrollment rate of recent high school

graduates for all races was 68%; Asian Americans had the highest

enrollment rate (78%), followed by Whites (70%), Hispanics (63%), and

Blacks (62%).

Asian students also had the highest 6-year college graduation rate

(74%), followed by Whites (64%), Hispanics (54%), and Blacks (40%). Even at prestigious institutions, the graduation rate of white students is higher than that of black students.

The college enrollment rate increased for each racial and ethnic group between 1980 and 2007, but the enrollment rates for Blacks and Hispanics

did not increase at the same rate as among White students. Between 1980

and 2007, the college enrollment rate for Blacks increased from 44% to

56% and the college enrollment rates for Hispanics increased from 50% to

62%. In comparison, the same rate increased from 49.8% to 77.7% for

Whites. There are no data for Asians or American Indians/Alaska Natives

regarding enrollment rates from the 1980s to 2007.

Illiteracy

African

Americans were once denied education. Even as late as 1947, about one

third of African Americans over 65 were considered to lack the literacy

to read and write their own names. By 1969, however, illiteracy

among African Americans was less than one percent, though African

Americans still lag in more stringent definitions of document literacy.

Inability to read, write or speak English in America today is largely an

issue for immigrants, mostly from Asia and Latin America.

Illiteracy rates by race: 1870 to 1979

| Year

|

White

|

Black

|

| 1870

|

11.5%

|

79.9%

|

| 1880

|

9.4%

|

70.0%

|

| 1890

|

7.7%

|

56.8%

|

| 1900

|

6.2%

|

44.5%

|

| 1910

|

5.0%

|

30.5%

|

| 1920

|

4.0%

|

23.0%

|

| 1930

|

3.0%

|

16.4%

|

| 1940

|

2.0%

|

11.5%

|

| 1947

|

1.8%

|

11.0%

|

| 1952

|

1.8%

|

10.2%

|

| 1959

|

1.6%

|

7.5%

|

| 1969

|

0.7%

|

3.6%

|

| 1979

|

0.4%

|

1.6%

|

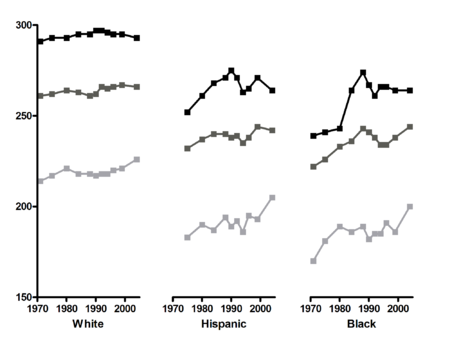

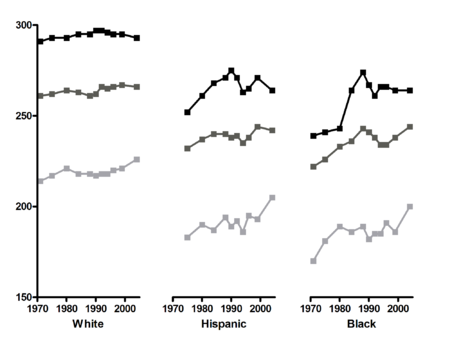

Long-term trends

The

National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) has been testing

seventeen-year-olds since 1971. From 1971 to 1996, the black-white

reading gap shrank by almost one half and the math gap by almost one

third.

Specifically, blacks scored an average of 239 points, and whites scored

an average of 291 points on the NAEP reading tests in 1971. In 1990,

blacks scored an average of 267, and whites scored an average of 297

points. On NAEP math tests in 1973, blacks scored an average of 270, and

whites scored 310. In 1990, black average score was 289 and whites

scored an average of 310 points. For Hispanics, the average NAEP math

score for seventeen-year-olds in 1973 was 277 and 310 for whites. In

1990, the average score among Hispanics was 284 compared with 310 for

whites.

Because of small population size in the 1970s, similar trend data

are not available for Asian Americans. Data from the 1990 NAEP

Mathematics Assessment Tests show that among twelfth graders, Asians

scored an average of 315 points compared with 301 points for whites, 270

for blacks, 278 for Hispanics, and 290 for Native Americans.

Racial and ethnic differentiation is most apparent at the highest

achievement levels. Specifically, 13% of Asians performed at level of

350 points or higher, 6% of whites, less than 1% of blacks, and 1% of

Hispanics did so.

The NAEP has since collected and analyzed data through 2008.

Overall, the White-Hispanic and the White-Black gap for NAEP scores have

significantly decreased since the 1970s.

The Black-White Gap demonstrates:

- In mathematics, the gap for 17-year-olds was narrowed by 14 points from 1973 to 2008.

- In reading, the gap for 17-year-olds was narrowed by 24 points from 1971 to 2008.

The Hispanic-White Gap demonstrates:

- In mathematics, the gap for 17-year-olds was narrowed by 12 points from 1973 to 2008.

- In reading, the gap for 17-year-olds was narrowed by 15 points from 1975 to 2008.

Furthermore, subgroups showed predominant gains in 4th grade at all

achievement levels. In terms of achieving proficiency, gaps between

subgroups in most states have narrowed across grade levels, yet had

widened in 23% of instances. The progress made in elementary and middle

schools was greater than that in high schools, which demonstrates the

importance of early childhood education. Greater gains were seen in

lower-performing subgroups rather than in higher-performing subgroups.

Similarly, greater gains were seen in Latino and African American

subgroups than for low-income and Native American subgroups.

- Reading- ages 9 (light gray), 13 (dark gray), and 17 (black).

International comparisons

As a whole, students in the United States lagged the leading Asian and European nations in the TIMSS international math and science test.

However, broken down by race, US Asians scored comparably to Asian

nations, and white Americans scored comparably to leading European

nations. Although some races generally score lower than whites in the

US, they scored as well as whites in European nations: Hispanic

Americans averaged 505, comparable to students in Austria and Sweden,

while African Americans, at 482, were comparable to students in Norway

and Ukraine.

Possible causes

The

achievement gap between low-income minority students and middle-income

white students has been a popular research topic among sociologists

since the publication of the report, "Equality of Educational

Opportunity" (more widely known as the Coleman Report).

This report was commissioned by the U.S. Department of Education in

1966 to investigate whether the performance of African-American students

was caused by their attending schools of a lesser quality than white

students. The report suggested that both in-school factors and

home/community factors affect the academic achievement of students and

contribute to the achievement gap that exists between races.

The study of the achievement gap can be addressed from two

standpoints—from a supply-side and a demand-side viewpoint of education.

In Poor Economics, Banerjee and Duflo explain the two families of arguments surrounding education of underserved populations.

Demand-side arguments focus on aspects of minority populations that

influence education achievement. These include family background and

culture, which shape perceptions and expectations surrounding education.

A large body of research has been dedicated to studying these factors

contributing to the achievement gap. Supply-side arguments focus on the

provision of education and resources and the systemic structures in

place that perpetuate the achievement gap. These include neighborhoods,

funding, and policy. In 2006, Ladson-Billings called on education

researchers to move the spotlight of education research away from family

background to take into account the rest of the factors that affect

educational achievement, as explained by the Coleman Report.

The concept of opportunity gaps—rather than achievement gaps—has

changed the paradigm of education research to assess education from a

top-down approach.

Social Belonging

A

person's sense of social belonging is one non-cognitive factor that

plays a part in the racial achievement gap. Some of the processes that

threaten a person's sense of belonging in schools include social stigma,

negative intellectual stereotypes, and numeric under-representation.

Walton and Cohen describe three ways in which a sense of social

belonging boosts motivation, the first being positive self-image. By

adopting similar interests as those who a person considers to be

socially significant, it may help to increase or affirm a person's sense

of his or her personal worth.

People have a basic need to belong, which is why people may feel a

sense of distress when social rejection occurs. Students in minority

groups have to battle other factors as well, such as peer and friend

groups being separated by race. Homogeneous friend groups can segregate

people out of important networking connections, thus limiting important

future opportunities that non-minority groups have because they have

access to these networking connections.

Oakland students that come from low socioeconomic families are less

likely to attend schools that provide equal education as wealthier

schools that come from major American cities. This means that only two

of ten students will go to schools that have a closing achievement gap.

Students who do not fall into the majority or dominant group in

their schools often worry about whether or not they will belong and find

a valued place in their school. Their thoughts are often centered

around whether they will be accepted and valued for who they are around

their peers. Social rejection can cause reductions in IQ test performance, self-regulation, and also can prompt aggression.

People can do more together than they can alone. Social life is a form

of collaborative activity, and an important feature of human life. When

goals and objectives become shared, they offer a person and the social

units he or she is a part of major advantages over if he or she was

working alone.

Under performing groups in schools often report that they feel

like they do not belong and that they are unhappy a majority of the

time. Steele offers an example, explaining an observation done by his

colleague, Treisman. It was observed that African American students at

Berkeley did their work independently in their rooms with nobody to

converse with. They spent most of their time checking answers to their

arithmetic in the back of their textbook, weakening their grasp of the

concepts themselves. This ultimately caused these students to do worse

on tests and assessments than their white peers, creating a frustrating

experience and also contributing to the racial achievement gap.

Another explanation that has been suggested for racial and ethnic

differences in standardized test performance is that some minority

children may not be motivated to do their best on these assessments.

Many argue that standardized IQ tests and other testing procedures are

culturally biased toward the knowledge and experiences of the

European-American middle class.

Purpose

When

students feel that what they are doing has purpose, they are more likely

to succeed academically. Students who identify and actively work

towards their individual, purposeful, life goals have a better chance at

eliminating disengagement that commonly occurs in middle school and

continues into later adolescence.

These life goals give students a chance to believe that their school

work is done in hopes of achieving larger, more long-term goals that

matter to the world. This also gives students the opportunity to feel

that their lives have meaning by working towards these goals.

Purposeful life goals, such as work goals, may also increase

students motivation to learn. Adolescents may make connections between

what they are learning in school and how they will use those skills and

knowledge will help them make an impact in the future. This idea

ultimately will lead students to create their own goals related to

mastering the material they are learning in school.

Adolescents who have goals and believe that their opinions and

voices can impact the world positively may become more motivated. They

become more committed to mastering concepts and being accountable for

their own learning, rather than focusing on getting the highest grade in

the class.

Students will study more intently and deeply, as well as persist

longer, seeking out more challenges. They will like learning more

because the tasks they are doing have purpose, creating a personal

meaning to them and in turn leading to satisfaction.

Mindset

Carol Dweck,

professor of psychology at Stanford University, suggests that students'

mindsets (how they perceive their own abilities) play a large role in

educational achievement and motivation. An adolescent's level of self-efficacy

is a great predictor of their level of academic performance, going

above and beyond a student's measured level of ability and also their

prior performance in school.

Students having a growth mindset believe that their intelligence can be

developed over time. Those with a fixed mindset believe that their

intelligence is fixed and cannot grow and develop. Students with growth

mindsets tend to outperform their peers who have fixed mindsets.

Dweck points out that teachers have a high degree of influence on

which kind of mindset a student develops in school. When people are

taught with a growth mindset, the ideas of challenging themselves and

putting in more effort follow.

People believe that each mindset is better than the other, which causes

students to feel that they are not as good as other students in school.

A big question that is asked in schooling is when does someone feel

smart: when they are flawless or when they are learning?

With a fixed mindset, you must be flawless, and not just smart in the

classroom. With this mindset, there is even more pressure on students to

not only succeed, but to be flawless in front of their peers.

Students who have a fixed mindset, have come to change the idea of failure as an action to an identity.

They come to think of the idea of failing something as being that they

are a failure and that they cannot achieve something. This links back

into how they think of themselves as a person and decreases their

motivation in school. This sense of "failure" is especially prominent

during adolescence. If one thing goes wrong, one with a fixed mindset

will feel that they cannot overcome this small failure, and thus their

mindset motivation will decrease.

Structural and institutional factors

Different

schools have different effects on similar students. Children of color

tend to be concentrated in low-achieving, highly segregated schools. In

general, minority students are more likely to come from low-income

households, meaning minority students are more likely to attend poorly

funded schools based on the districting patterns within the school

system. Schools in lower-income districts tend to employ less qualified

teachers and have fewer educational resources.

Research shows that teacher effectiveness is the most important

in-school factor affecting student learning. Good teachers can actually

close or eliminate the gaps in achievement on the standardized tests

that separate white and minority students.

Schools also tend to place students in tracking

groups as a means of tailoring lesson plans for different types of

learners. However, as a result of schools placing emphasis on

socioeconomic status and cultural capital, minority students are vastly

over-represented in lower educational tracks.

Similarly, Hispanic and African American students are often wrongly

placed into lower tracks based on teachers' and administrators'

expectations for minority students. Such expectations of a race within

school systems are a form of institutional racism. Some researchers compare the tracking system to a modern form of racial segregation within the schools.

Studies on tracking groups within schools have also proven to be detrimental for minority students.

Once students are in these lower tracks, they tend to have

less-qualified teachers, a less challenging curriculum, and few

opportunities to advance into higher tracks.

There is also some research that suggests students in lower tracks

suffer from social psychological consequences of being labeled as a

slower learner, which often leads children to stop trying in school. In fact, many sociologists argue that tracking in schools does not provide any lasting benefits to any group of students.

The practice of awarding low grades and test scores to children

who struggle causes low-performing children to experience anxiety,

demoralization, and a loss of control. This undermines performance,

and may explain why the achievement gap increases over the school

years, and why the interventions implemented thus far seem to have

failed to close it.

School funding and geography

The

quality of school that a student attends and the socioeconomic status

of the student's residential neighborhood are two factors that can

affect a student's academic performance.

In the United States, only 8% of public education funding comes

from the federal government. The other 92% comes from local, state, and

private sources.

Local funding is considered unequal as it is based on property taxes.

So those who are in areas in which there is lower property value have

less funded schools, making schools unequal within a district. This system means that schools located in areas with lower real estate

values have proportionately less money to spend per pupil than schools

located in areas with higher real estate values. This system has also

maintained a "funding segregation": because minority students are much

more likely to live in a neighborhood with lower property values, they

are much more likely to attend a school that receives significantly

lower funding.

Data from research shows that when the quality of the school is

better and students are given more resources, it reduces the racial

achievement gap. When white and black schools were given the equal

amount of resources, it shows that black students started improving

while white students stayed the same because they didn't need the

resources. This showed that lack of resources is a factor in the racial

achievement gap.

The research that was conducted shows that predominantly white schools

have more resources than black schools. However, lack of resources is

only a small effect on academic achievement in comparison to students'

family backgrounds.

Using property taxes to fund public schools contributes to school

inequality. Lower-funded schools are more likely to have lower-paid

teachers; higher student-teacher ratios, meaning less individual

attention for each student; older books; fewer extracurricular

activities, which have been shown to increase academic achievement;

poorly maintained school facilities; and less access to services like

school nursing and social workers. All of these factors can affect

student performance and perpetuate inequalities between students of

different races.

Living in a high-poverty or disadvantaged neighborhood have been

shown to negatively influence educational aspirations and consequently

attainment. The Moving to Opportunity

experiment showed that moving to a low-poverty neighborhood had a

positive effect on the educational attainment of minority adolescents.

The school characteristics associated with the low-poverty neighborhoods

proved to be effective mediators, since low-poverty neighborhoods

tended to have more favorable school composition, safety, and quality.

Additionally, living in a neighborhood with economic and social

inequalities leads to negative attitudes and more problematic behavior

due to and social tensions. Greater college aspirations have been correlated with more social cohesiveness

among neighborhood youth, since community support from both youth and

adults in the neighborhood tends to have a positive influence on

educational aspirations.

Some researchers believe that vouchers should be given to low income

students so they can go to school in other places. However, other

researchers believe that the idea of vouchers promotes equality and

doesn't eliminate it.

Racial and ethnic residential segregation

in the United States still persists, with African Americans

experiencing the highest degree of residential segregation, followed by

Latino Americans and Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders.

This isolation from white American communities is highly correlated

with low property values and high-poverty neighborhoods. This issue is

propagated by issues of home ownership facing minorities, especially

African Americans and Latino Americans, since residential areas

predominantly populated by these minority groups are perceived as less

attractive in the housing market. Home ownership by minority groups is

further undermined by institutionalized discriminatory practices, such

as differential treatment of African Americans and Latino Americans in

the housing market compared with white Americans. Higher mortgages

charged to African American or Latino American buyers make it more

difficult for members of these minority groups to attain full home

ownership and accumulate wealth. As a result, African American and

Latino American groups continue to live in racially segregated

neighborhoods and face the socioeconomic consequences of residential

segregation.

Differences in the academic performance of African-American and

white students exist even in schools that are desegregated and diverse,

and studies have shown that a school's racial mix does not seem to have

much effect on changes in reading scores after sixth grade, or on math

scores at any age.

In fact, minority students in segregated-minority schools have more

optimism and greater educational aspirations as well as achievements

than minority students in segregated-white schools. This can be

attributed to various factors, including the attitudes of faculty and

staff at segregated-white schools and the effect of stereotype threat.

Education Debt

Education debt is a theory developed by Gloria Ladson-Billings,

a pedagogical theorist, to attempt to explain the racial achievement

gap. As defined by a colleague of Ladson-Billings, Professor Emeritus

Robert Haveman, education debt is the "foregone schooling resources that

we could have (should have) been investing in (primarily) low income

kids, which deficit leads to a variety of social problems (e.g. crime,

low productivity, low wages, low labor force participation) that require

on-going public investment". The education debt theory has historical, economic, sociopolitical and moral components.

Parenting influence

Parenting methods are different across cultures, thus can have dramatic influence on educational outcomes.

For instance, Asian parents often apply strict rules and parental

authoritarianism to their children while many white American parents

deem creativity and self-sufficiency to be more valuable. Battle Hymn of the Tiger Mother

by Yale Professor Amy Chua highlights some of the very important

aspects in East Asian parenting method in comparison to the "American

way". Chua's book has generated interests and controversies in the

"Tiger Mom" parenting method and its role in determining children's

education outcomes. Many Hispanic parents and their children believe that a college degree is necessary for obtaining stable and meaningful work.

This attitude is reflected in the educational expectations parents hold

for their children and in the expectations that young people have for

themselves (U.S. Department of Education, 1995b, p. 88).

High educational expectations can be found among all racial and ethnic

groups regardless of their economic and social resources (p. 73).

Although parents and children share high educational aims, their

aspirations do not necessarily translate into postsecondary

matriculation. This is especially the case for Hispanic high school

students, particularly those whose parents have not attended college.

Parental involvement in children's education is influential to children's success at school.

Teachers often view low parental involvement as a barrier to student

success. Collaboration between teachers and parents is necessary when

working to help a child; parents have the necessary knowledge of what is

best for their child's situation.

However, the student body in schools is diverse, and although teachers

make an effort to try and understand each child's unique cultural

beliefs, it is important that they are meeting with parents to get a

clear understanding of what needs should be met in order for the student

to succeed. School administrators must accommodate and account for

family differences and also be supportive by promoting ways families can

get involved. For example, schools can provide support by accommodating

the needs of the family who have do not have transportation, schools

may do so by providing external resources that may benefit the family.

As referenced by Feliciano et al. (2016), educators can also account

for culture by providing education about the diversity at the school.

This can be achieved by creating an environment where both teachers and

students learn about cultures represented among the student population.

Larocquem et al. (2011) stated that family involvement may

include visiting their children's class, being involved with a parent

teacher organization, attending school activities, speaking to the

child's class, and volunteering at school events. It is also important

for families to be involved with the child's school assignments,

especially by holding them accountable for completion and discussion of

the work assigned.

Also, educators may want to consider how parental language barriers and

educational experiences affect families and the influence of

contributing to their child's education.

In addition, even when families want to get involved, they may not know

how to collaborate with school personnel, especially for families who

are Hispanic, African American, and or of low economic status.

A study done by Nistler and Maiers (2000), found that although

different barriers for families may inhibit participation, families

reported that they would want to participate nonetheless.

Larocque et al. (2011) suggest that teachers need to find out what

values and expectations are held for the child, which should be done by

involving parents in the decision-making process.

Children can differ in their readiness to learn before they enter school.

Research has shown that parental involvement in a child's development

has a significant effect on the educational achievement of minority

children. According to sociologist Annette Lareau, differences in parenting styles can affect a child's future achievement. In her book Unequal Childhoods, she argues that there are two main types of parenting: concerted cultivation and the achievement of natural growth.

- Concerted cultivation

is usually practiced by middle-class parents, regardless of their race.

These parents are more likely to be involved in their children's

education, encourage their children's participation in extracurricular

activities or sports teams, and to teach their children how to

successfully communicate with authority figures. These communication

skills give children a form of social capital that help them communicate

their needs and negotiate with adults throughout their life.

- The achievement of natural growth is generally practiced by poor and

working-class families. These parents generally do not play as large a

role in their children's education, their children are less likely to

participate in extracurriculars or sports teams, and they usually do not

teach their children the communication skills that middle- and

upper-class children have. Instead, these parents are more concerned

that their children obey authority figures and have respect for

authority, which are two characteristics that are important to have in

order to succeed in working-class jobs.

The parenting practices that a child is raised with influences their

future educational achievement. However, parenting styles are heavily

influenced by the parents' and family's social, economic, and physical

circumstances. In particular, immigration status (if applicable),

education level, incomes, and occupations influence the degree of

parental involvement their children's academic achievement.

These factors directly determine the access of the parents to time and

resources to dedicate to their children's development. These factors

also indirectly determine the home environment and parents' educational

expectations of their children.

For example, children from poor families have lower academic

performance in kindergarten than children from middle to upper-class

backgrounds, but children from poor families who had cognitively

stimulating materials in the home demonstrated higher rates of academic

achievement in kindergarten. Additionally, parents of children living in

poverty are less likely to have cognitively stimulating materials in

the home for their children and are less likely to be involved in their

child's school.

The quality of language that the student uses is affected by family's

socioeconomic backgrounds, which is another factor in the academic

achievement gap.

Preschool education

Additionally,

poor and minority students have disproportionately less access to

high-quality early childhood education, which has been shown to have a

strong impact on early learning and development. One study found that

although black children are more likely to attend preschool than white

children, they may experience lower-quality care.

The same study also found that Hispanic children in the U.S. are much

less likely to attend preschool than white children. Another study

conducted in Illinois in 2010

found that only one in three Latino parents could find a preschool slot

for his or her child, compared to almost two thirds of other families.

Finally, according to the National Institute for Early Education

Research (NIEER), families with modest incomes (less than $60,000) have

the least access to preschool education.

Research suggests that dramatic increases in both enrollment and

quality of prekindergarten programs would help to alleviate the school

readiness gap and ensure that low-income and minority children begin

school on even footing with their peers.

Income

In the United States, socioeconomic status of families affects children schooling.

Sociologist Laura Perry found what she calls 'Student Socioeconomic

Status' has the third strongest influence on educational outcomes in the

United States out of nations within this study and it ranked sixth in

influence of equity differences among schools. These families are more susceptible to multidimensional poverty,

meaning the three dimensions of poverty, health, education, and

standard of living are interconnected to give an overall assessment of a

nations poverty.

Some researchers, such as Katherine Paschall, argue that family

income plays more of a factor in the academic achievement gap than

race/ethnicity.

However, other studies find that the racial gaps persists between

families of different race and ethnicity that have similar incomes. When

comparing white students from families with incomes below $10,000 they

had a mean SAT test score that was 61 points higher than African

American students whose families had incomes between $80,000 and

$100,000. This means that there are more contributing factors than just economic status.

Conservative African American scholars such as Thomas Sowell observe that while SAT scores are lower for students with less parental education and income,

Asian Americans who took the SAT with incomes below $10,000 score 482

in math in 1995, comparable to whites earning $30–40,000 and higher and

blacks over $70,000.

Similarly, a later study reveals that for the 2003 college bound

cohort, Black test-takers with more than $100,000 in family income have

mean SAT math and verbal scores of 490 and 495 respectively, and this is

comparable with the scores of the White test-takers with

$20,000-$25,000 in family income (493 and 495). Test scores in middle-income black communities, such as Charles County and Prince George's County, are still not comparable to those in non-black suburbs.

Economic factors were identified as lack of online course access (McCoy, 2012) and online course attrition which indicated before (Liu et al., 2007). Based on the National Center for Educational Statistic (2015),

about half of African American male students grew up in single-parent

households. They are associated with higher incidences of poverty, which

leads to poorer educational outcomes (Child Trends Databank, 2015).

Low-income households tend to have fewer home computers and less access

to the Internet (Zickuhr & Smith, 2012).

Cultural differences

Some

experts believe that cultural factors contribute to the racial

achievement gap. Students from minority cultures face language barriers,

differences in cultural norms in interactions, learning styles, varying

levels of receptiveness of their culture to white American culture, and

varying levels of acceptance of the white American culture by the

students. In particular, it has been found that minority students from

cultures with views that generally do not align with the mainstream

cultural views have a harder time in school.

Furthermore, views of the value of education differ by minority groups

as well as members within each group. Both Hispanic and African-American

youths often receive mixed messages about the importance of education,

and often end up performing below their academic potential.

Online education

Achievement

gaps between African American students and White students in online

classes tend to be greater than regular class. Expanding from 14% in

1995 to 22% in 2015 (National Center for Education Statistics, 2016). Possible causes include differences in socio-economic status (Palmer et al., 2013), academic performance differences (Osborne, 2001), technology inaccessibility (Fairlie, 2012), lack of online technical support (Rovai & Gallien, 2005), and anxiety towards racial stereotyping (Osborne, 2001).

Nowadays, there is a growing population of students who use

online education, and the number of institutions which offering fully

online degrees is also increasing. According to several studies, online

education probably could create an environment where there is less

cultural division and negative stereotypes of African Americans, thus

protecting those students who have had bad experiences. In addition, the

influence technology and user skills and so as economics and academic

influences are tightly bonded, that may have positively contributed to

African American online learners experience. However, it appears African

American male students are less likely to enroll in online classes.

Latino American cultural factors

Many

Hispanic parents who immigrate to The United States see a high school

diploma as being a sufficient amount of schooling and may not stress the

importance of continuing on to college. Parental discouragement from

pursuing higher education tends to be based on the notion of "we made it

without formal schooling, so you can too". Additionally, depending on

the immigration generation and economic status of the student, some

students prioritize their obligations to assisting their family over

their educational aspirations. Poor economic circumstances place greater

pressure on the students to sacrifice time spent working towards

educational attainment in order to dedicate more time to help support

the family. Surveys have shown that while Latino American families would

like their children to have a formal education, they also place high

value on getting jobs, marrying, and having children as early as

possible, all of which conflict with the goal of educational

achievement.

However, counselors and teachers usually promote continuing on to

college. This message conflicts with the one being sent to Hispanic

students by their families and can negatively affect the motivation of

Hispanic students, as evidenced by the fact that Latinos have the lowest

college attendance rates of any racial/ethnic group.

Overall, Latino American students face barriers such as financial

stability and insufficient support for higher education within their

families. Reading to children when they are younger increases literacy

comprehension, which is a fundamental concept in the education system;

however, it is less likely to occur within Latino American families

because many parents do not have any formal education. Currently, Latino

Americans over the age of 25 have the lowest percentage in obtaining a

bachelor's degree or higher amongst all other racial groups; while only

having 11 percent.

Disadvantages in a child's early life can cultivate into

achievement gaps in their education. Poverty, coupled with the

environment they are raised in, can lead to shortcomings in educational

achievement. Despite strong standards and beliefs in education, Hispanic

children consistently perform poorly, reflected by a low average of

math and reading scores, as compared to other groups except African

American.

Hispanic and African American children have been shown to be more

likely to be raised in poverty, with 33% of Hispanic families living

below the economic poverty level, compared to African American (39%), Asian (14%) and White (13%) counterparts.

Children who are raised in poverty are less likely to be enrolled in

nursery or preschool. Though researchers are seeing improvements in

achievement levels, such as a decrease in high school dropout rates

(from 24% to 17%) and a steady increase in math and reading scores over

the past 10 years, there are still issues that must be addressed.

There is a common misconception that Hispanic parents are not

involved in their child's education and fail to transmit strong

educational values to their children. However, there is evidence that

Hispanic parents actually hold their children's education in high value.

The majority of Hispanic children are affected by immigration. It affects recent immigrants as well as the children of immigrants.

Both recent immigrants and the children of immigrants are faced with

language barriers and other migration obstacles. A study explored the

unique situation and stressors recent Latin American immigrants face.

Hispanic students showed lower academic achievement, more absences, and

more life stressors than their counterparts. In 2014–2015, 77.8% of Hispanic children were English Language learners.

This can be problematic because children may not have parents who speak

English at home to help with language acquisition. Immigration

struggles can be used as a motivator for students. Immigrant parents

appeal to their children and hold high expectations because of the

"gift" they are bestowing on them. They immigrated and sacrificed their

lives so their children can succeed, and this framework is salient in

encouraging children to pursue their education. Parents use their

struggles and occupation to encourage a better life.

Parental involvement

has been shown to increase educational success and attainment for

students. For example, parental involvement in elementary school has

been shown to lower high school dropout rates and improved on time

completion of high school.

A common misconception is that Latino parents don't hold their

children's education in high regards (Valencia, 2002), but this has been

debunked. Parents show their values in education by holding high

academic expectations and giving "consejos" or advice. In 2012, 97% of

families reported teaching their children letters, words or numbers. A study reported that parent involvement during adolescence continues to be as influential as in early childhood.

African American cultural factors

The

culture and environment in which children are raised may play a role in

the achievement gap. Jencks and Phillips argue that African American

parents may not encourage early education in toddlers because they do

not see the personal benefits of having exceptional academic skills. As a

result of cultural differences, African American students tend to begin

school with smaller vocabularies than their white classmates.

Hart and Risley calculated a "30 million word gap" between children of

high school dropouts and those of professionals who are college

educated. The differences are qualitative as well as quantitative, with

differences in "unique" words, complexity, and "conversational turns."

However, poverty often acts as a confounding factor and

differences that are assumed to arise from racial/cultural factors may

be socioeconomically driven, as can be seen by a study where

immigrant-origin Black undergraduates outperformed U.S.-origin Black

undergraduates until socioeconomic status was taken into account.

Many children who are poor, regardless of race, come from homes that

lack stability, continuity of care, adequate nutrition, and medical care

creating a level of environmental stress that can affect the young

child's development. As a result, these children enter school with

decreased word knowledge that can affect their language skills,

influence their experience with books, and create different perceptions

and expectations in the classroom context.

Studies show that when students have parental assistance with homework, they perform better in school.

This is a problem for many minority students due to the large number of

single-parent households (67% of African-American children are in a

single-parent household)

and the increase in non-English speaking parents. Students from

single-parent homes often find it difficult to find time to receive help

from their parent. Similarly, some Hispanic students have difficulty

getting help with their homework because there is not an English speaker

at home to offer assistance.

African American students are also likely to receive different

messages about the importance of education from their peer group and

from their parents. Many young African-Americans are told by their

parents to concentrate on school and do well academically, which is

similar to the message that many middle-class white students receive.

However, the peers of African-American students are more likely to place

less emphasis on education, sometimes accusing studious

African-American students of "acting white".

This causes problems for black students who want to pursue higher

levels of education, forcing some to hide their study or homework habits

from their peers and perform below their academic potential.

As some researchers point out, minority students may feel little

motivation to do well in school because they do not believe it will pay

off in the form of a better job or upward social mobility. By not trying to do well in school, such students engage in a rejection of the achievement ideology

– that is, the idea that working hard and studying long hours will pay

off for students in the form of higher wages or upward social mobility.

Asian American cultural factors

Asian American students are more likely to view education as a means to social mobility and career advancement.

It may also provide a means to overcome discrimination as well as

language barriers. This notion comes from cultural expectations and

parental expectations of their children, which are rooted in the

cultural belief that education and hard work is the key to educational

and eventually occupational attainment. Many Asian Americans immigrated

to the United States voluntarily, in search for better opportunities.

This immigration status comes into play when assessing the cultural

views of Asian Americans since attitudes of more recent immigration are

associated with optimistic views about the correlation between hard work

and success. Obstacles such as language barriers and acceptance of

white American culture are more easily overcome by voluntary immigrants

since their expectations of attaining better opportunities in the United

States influence their interactions and experiences.

Students that identify as Asian American believe that having a good

education would also help them speak out against racism based on the

model-minority stereotype.

Factors specific to refugees

Part

of the racial achievement gap can be attributed to the experience of

the refugee population in the United States. Refugee groups in

particular face obstacles such as cultural and language barriers and

discrimination, in addition to migration-related stresses. These factors

affect how successfully refugee children can assimilate to and succeed

in the United States.

Furthermore, it has been shown that immigrant children from politically

unstable countries do not perform as well as immigrant children from

politically stable countries.

Genetic factors

Scientific

consensus tells us that there is no genetic component behind

differences in academic achievement between racial groups. However, pseudoscientific

claims that certain racial groups are intellectually superior and

others inferior continue to circulate. A recent example is Herrnstein

and Murray's 1994 book The Bell Curve, which controversially claimed that variation in average levels of intelligence

(IQ) between racial groups are genetic in origin, and that this may

explain some portion of the racial disparities in achievement. The book has been described by many academics as a restatement of previously debunked "scientific racism", and was condemned by both literary reviewers and academics within related fields.

The consensus view among scientists is that there is no difference in

inherent cognitive ability between different races, and that environment

is at the root of the achievement gap.

Implications

Sociologists Christopher Jencks

and Meredith Phillips have argued that narrowing the black-white test

score gap "would do more to move [the United States] toward racial

equality than any politically plausible alternative". There is also strong evidence that narrowing the gap would have a significant positive economic and social impact.

Economic outcomes

The

racial achievement gap has consequences on the life outcomes of

minority students. However, this gap also has the potential for negative

implications for American society as a whole, especially in terms of

workforce quality and the competitiveness of the American economy.

As the economy has become more globalized and the United States'

economy has shifted away from manufacturing and towards a

knowledge-based economy, education has become an increasingly important

determinant of economic success and prosperity. A strong education is

now essential for preparing and training the future workforce that is

able to compete in the global economy. Education is also important for

attaining jobs and a stable career, which is critical for breaking the cycle of poverty

and securing a sound economic future, both individually and as a

nation. Students with lower achievement are more likely to drop out of

high school, entering the workforce with minimal training and skills,

and subsequently earning substantially less than those with more

education. Therefore, eliminating the racial achievement gap and

improving the achievement of minority students will help eliminate

economic disparities and ensure that America's future workforce is well

prepared to be productive and competitive citizens.

Reducing the racial achievement gap is especially important

because the United States is becoming an increasingly diverse country.

The percentage of African-American and Hispanic students in school is

increasing: in 1970, African-Americans and Hispanics made up 15% of the

school-age population, and that number had increased to 30% by 2000. It

is expected that minority students will represent the majority of school

enrollments by 2015.

Minorities make up a growing share of America's future workforce;

therefore, the United States' economic competitiveness depends heavily

on closing the racial achievement gap.

The racial achievement gap affects the volume and quality of

human capital, which is also reflected through calculations of GDP. The

cost of racial achievement gap accounts for 2–4 percent of the 2008 GDP.

This percentage is likely to increase as blacks and Hispanics continue

to account for a higher proportion of the population and workforce.

Furthermore, it was estimated that $310 billion would be added to the US

economy by 2020 if minority students graduated at the same rate as

white students.

Even more substantial is the narrowing of educational achievement

levels in the US compared to those of higher-achieving nations, such as

Finland and Korea. McKinsey & Company estimate a $1.3 trillion to

$2.3 trillion, or a 9 to 16 percent difference in GDP.

Furthermore, if high school dropouts were to cut in half, over $45

billion would be added in savings and additional revenue. In a single

high school class, halving the dropout rate would be able to support

over 54,000 new jobs, and increase GDP by as much as $9.6 billion. Overall, the cost of high school drop outs on the US economy is roughly $355 billion.

$3.7 billion would be saved on community college remediation

costs and lost earnings if all high school students were ready for

college. Furthermore, if high school graduation rates for males raised

by 5 percent, cutting back on crime spending and increasing earnings

each year would lead to an $8 billion increase the US economy.

A 2009 report by the management consulting firm McKinsey & Company asserts that the persistence of the achievement gap in the U.S. has the economic effect of a "permanent national recession."

The report claims that if the achievement gap between black and Latino

performance and white student performance had been narrowed, GDP in 2008

would have been $310 billion to $525 billion higher (2–4 percent).

If the gap between low-income students and their peers had been

narrowed, GDP in the same year would have been $400 billion to $670

billion higher (3–5 percent). In addition to the potential increase in

GDP, the report projects that closing the achievement gap would lead to

cost savings in areas outside of education, such as incarceration and

healthcare. The link between low school performance and crime, low

earnings and poor health has been echoed in academic research.

Job opportunities

As

the United States' economy has moved towards a globalized

knowledge-based economy, education has become even more important for

attaining jobs and a stable career, which is critical for breaking the

cycle of poverty and securing a sound economic future. The racial

achievement gap can hinder job attainment and social mobility for

minority students. The United States Census Bureau reported $62,545 as the median income of white families, $38,409 of Black families, and $39,730 for Hispanic families.

And while the median income of Asian families is $75,027, the number of

people working in these households is usually greater than that in

white American families. The difference in income levels relate highly to educational opportunities between various groups.

Students who drop out of high school as a result of the racial

achievement gap demonstrate difficulty in the job market. The median

income of young adults who do not finish high school is about $21,000,

compared to the $30,000 of those who have at least earned a high school

credential. This translates into a difference of $630,000 in the course

of a lifetime.

Students who are not accepted or decide not to attend college as a

result of the racial achievement gap may forgo over $450,000 in lifetime

earnings had they earned a Bachelor of Arts degree.

In 2009, $36,000 was the median income for those with an associate

degree was, $45,000 for those with a bachelor's degree, $60,000 for

those with a master's degree or higher.

Stereotype threat

Beyond

differences in earnings, minority students also experience stereotype

threats that negatively affects performance through activation of

salient racial stereotypes. The stereotype threat both perpetuates and is caused by the achievement gap. Furthermore, students of low academic performance demonstrate low expectations for themselves and self-handicapping tendencies. Psychologists Claude Steele, Joshua Aronson, and Steven Spencer, have found that Microaggression

such as passing reminders that someone belongs to one group or another

(i.e.: a group stereotyped as inferior in academics) can affect test

performance.

Steele, Aronson and Spencer, have examined and performed

experiments to see how stereotypes can threaten how students evaluate

themselves, which then alters academic identity and intellectual

performance. Steele tested the stereotype threat theory by giving Black

and white college students a half-hour test using difficult questions

from the verbal Graduate Record Examination

(GRE). In the stereotype-threat condition, they told students the test

diagnosed intellectual ability. In saying that the test diagnoses

intellectual ability it can potentially elicit the stereotype that

Blacks are less intelligent than whites. In the no-stereotype-threat

condition, they told students that the test was a problem-solving lab

task that said nothing about ability. This made stereotypes irrelevant.

In the stereotype threat condition, Blacks who were evenly matched with

whites in their group by SAT scores, performed worse compared to their

white counterparts. In the experiments with no stereotype threat, Blacks

performed slightly better than in those with a stereotype threat,

though still significantly worse than whites. Aronson believes the study

of stereotype threat offers some "exciting and encouraging answers to

these old questions [of achievement gaps] by looking at the psychology

of stigma -- the way human beings respond to negative stereotypes about

their racial or gender group".

Claude M. Steele suggested that minority children and adolescents may also experience stereotype threat—the

fear that they will be judged to have traits associated with negative

appraisals and/or stereotypes of their race or ethnic group. According

to this theory, this produces test anxiety

and keeps them from doing as well as they could on tests. According to

Steele, minority test takers experience anxiety, believing that if they

do poorly on their test they will confirm the stereotypes about inferior

intellectual performance of their minority group. As a result, a self-fulfilling prophecy begins, and the child performs at a level beneath his or her inherent abilities.

Political representation

Another

consequence of the racial achievement gap can be seen in the lack of

representation of minority groups in public office. Studies have shown

that higher socioeconomic status—in terms of income, occupation, and/or

educational attainment—is correlated with higher participation in

politics.

This participation is defined as "individual or collective action at

the national or local level that supports or opposes state structures,

authorities, and/or decisions regarding allocation of public goods"; this action ranges from engaging in activities such as voting in elections to running for public office.

Since median income per capita for minority groups (except

Asians) is lower than that of white Americans, and since minority groups

(except Asians) are more likely to occupy less gainful employment and

achieve lower education levels, there is a lowered likelihood of

political participation among minority groups. Education attainment is

highly correlated with earnings and occupation.

And there is a proven disparity between educational attainment of white

Americans and minority groups, with only 30% of bachelor's degrees

awarded in 2009 to minority groups. Thus socioeconomic status—and therefore political participation—is correlated with race.

Research has shown that African Americans, Latino Americans, and Asian

Americans are less politically active, by varying degrees, than white

Americans.

A consequence of underrepresentation of minority groups in

leadership is incongruence between policy and community needs. A study

conducted by Kenneth J. Meier and Robert E. England of 82 of the largest

urban school districts in the United States showed that African

American membership on the school board of these districts led to more

policies encouraging more African American inclusion in policy

considerations.

It has been shown that both passive and active representation of

minority groups serves to align constituent policy preference and

representation of these opinions, and thereby facilitate political

empowerment of these groups.

Special programs

Achievement gaps among students may also manifest themselves in the racial and ethnic composition of special education and gifted education

programs. Typically, African American and Hispanic students are

enrolled in greater numbers in special education programs than their

numbers would indicate in most populations, while these groups are

underrepresented in gifted programs.

Research shows that these disproportionate enrollment trends may be a

consequence of the differences in educational achievement among groups.

Efforts to narrow the achievement gap

The

United States has seen a variety of different attempts to narrow the

racial achievement gap. These attempts include focusing on the

importance of early childhood education, using federal standards based