Northern gannet pair

In biology, a pair bond is the strong affinity that develops in some species

between a mating pair, often leading to the production and rearing of

offspring and potentially a lifelong bond. Pair-bonding is a term coined

in the 1940s that is frequently used in sociobiology and evolutionary biology circles. The term often implies either a lifelong socially monogamous

relationship or a stage of mating interaction in socially monogamous

species. It is sometimes used in reference to human relationships.

Monogamous voles (such as prairie voles) have significantly greater density and distribution of vasopressin

receptors in their brain when compared to polygamous voles. These

differences are located in the ventral forebrain and the

dopamine-mediated reward pathway.

Peptide arginine vasopressin (AVP), dopamine, and oxytocin

act in this region to coordinate rewarding activities such as mating,

and regulate selective affiliation. These species-specific differences

have shown to correlate with social behaviors, and in monogamous prairie

voles are important for facilitation of pair bonding. When compared to montane voles, which are polygamous, monogamous prairie voles appear to have more of these AVP and oxytocin neurotransmitter receptors. It is important that these receptors are in the reward centers of the brain because that could lead to a conditioned

partner in the prairie vole compared to the montane vole which would

explain why the prairie vole forms pair bonds and the montane vole does

not.

Varieties

Black-backed jackals are one of very few monogamous

mammals. This pair works together in teamwork to hunt down prey and

scavenge. They will stay together until one of the two dies.

According to evolutionary psychologists David P. Barash and Judith Lipton, from their 2001 book The Myth of Monogamy, there are several varieties of pair bonds:

- Short-term pair-bond: a transient mating or associations

- Long-term pair-bond: bonded for a significant portion of the life cycle of that pair

- Lifelong pair-bond: mated for life

- Social pair-bond: attachments for territorial or social reasons, as in cuckold situations

- Clandestine pair-bond: quick extra-pair copulations

- Dynamic pair-bond: e.g. gibbon mating systems being analogous to "swingers"

Humans and pair bonding

Pair-bonded human male and female

Humans can experience some or all of the above-mentioned varieties of

pair bonds in their lifetime. These bonds can be temporary or last a

lifetime, same age or with different age groups. In a biological sense

there are two main types of pair bonds exhibited in humans: social pair bonding and sexual

pair bonding. The social pair bond is a strong behavioral and

psychological relationship between two individuals that is measurably

different in physiological and emotional terms from general friendships or other acquaintance relationships.

On the other hand, the sexual pair bond is a behavioral and

physiological bond between two individuals with a strong sexual

attraction component. In this bond the participants in the sexual pair

bond prefer to have sex with each other over other options. Social pair

bonds are usually more wide-ranging than their sexual counterparts due

to the sexual nature involved in the latter. In humans and other mammals, these pair bonds are created by a combination of social interaction and biological factors including neurotransmitters like oxytocin, vasopressin, and dopamine.

Pair bonds (social and/or sexual) are a biological phenomenon and are not equivalent to the human social institution of marriage.

Marriage can be associated with a sexual or social pair bond; however,

married couples do not necessarily have to experience both or either of

these bonds. Marriage can be a consequence of pair bonding and vice

versa; however, neither always creates or leads to the other. Pair

bonding in humans helps explain extreme "bonds" that we may share with others but are unable to articulate in terms of contemporary "love".

Examples

Birds

Close to ninety percent of known avian species are monogamous,

compared to five percent of known mammalian species. The majority of

monogamous avians form long-term pair bonds which typically result in

seasonal mating: these species breed with a single partner, raise their

young, and then pair up with a new mate to repeat the cycle during the

next season. Some avians such as swans, bald eagles, California condors, and the Atlantic Puffin are not only monogamous, but also form lifelong pair bonds.

When discussing the social life of the bank swallow, Lipton and Barash state:

For about four days immediately prior to egg-laying, when copulations lead to fertilizations, the male bank swallow is very busy, attentively guarding his female. Before this time, as well as after—that is, when her eggs are not ripe, and again after his genes are safely tucked away inside the shells—he goes seeking extra-pair copulations with the mates of other males…who, of course, are busy with defensive mate-guarding of their own.

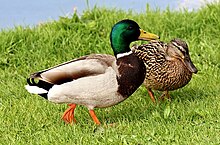

Male (left) and female (right) mallard ducks form seasonal monogamous pairs.

In various species, males provide parental care and females mate with

multiple males. For example, recent studies show that extra-pair

copulation frequently occurs in monogamous birds in which a "social"

father provides intensive care for its "social" offspring.

Fishes

A University of Florida scientist reports that male sand gobies

work harder at building nests and taking care of eggs when females are

present – the first time such “courtship parental care” has been

documented in any species.

In the cichlid species Tropheus moorii, a male and female will form a temporary monogamous pair bond and spawn; after which, the female leaves to mouthbrood the eggs on her own. T. moorii broods exhibit genetic monogamy (all eggs in a brood are fertilized by a single male). Another mouth brooding cichlid - the Lake Tanganyika cichlid (Xenotilapia rotundiventralis) has been shown that mating pairs maintain pair bonds at least until the shift of young from female to male. More recently the Australian Murray cod has been seen maintaining pair bonds over 3 years

Mammals

As

noted above, different species of voles vary in their sexual behavior,

and these differences correlate with expression levels of vasopressin

receptors in reward areas of the brain. Scientists were able to change

adult male montane voles' behavior to resemble that of monogamous

prairie voles in experiments in which vasopressin receptors were

introduced into the brain of male montane voles.