A detail from Benjamin West's heroic, neoclassical history painting, The Death of General Wolfe (1771), depicting an idealized Native American.

The idea that humans are essentially good is often attributed to the 3rd Earl of Shaftesbury, a Whig supporter of constitutional monarchy. In his Inquiry Concerning Virtue (1699), Shaftesbury had postulated that the moral sense in humans is natural and innate and based on feelings, rather than resulting from the indoctrination of a particular religion. Shaftesbury was reacting to Thomas Hobbes's justification of an absolutist central state in his Leviathan, "Chapter XIII", in which Hobbes famously holds that the state of nature is a "war of all against all" in which men's lives are "solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short". Hobbes further calls the American Indians an example of a contemporary people living in such a state. Although writers since antiquity had described people living in pre-civilized conditions, Hobbes is credited with inventing the term "State of Nature". Ross Harrison writes that "Hobbes seems to have invented this useful term."

Contrary to what is sometimes believed, Jean-Jacques Rousseau never used the phrase noble savage (French bon sauvage). However, the character of the noble savage appeared in French literature at least as early as Jacques Cartier (coloniser of Québec, speaking of the Iroquois) and Michel de Montaigne (philosopher, speaking of the Tupinamba) in the 16th century.

Pre-history of the noble savage

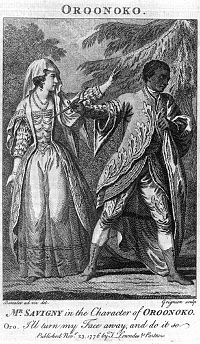

Oroonoko kills Imoinda in a 1776 performance of Thomas Southerne's Oroonoko.

Tacitus' De origine et situ Germanorum (Germania), written c. 98 AD, has been described as a predecessor of the modern noble savage concept, which started in the 17th and 18th centuries in western European travel literature.

During the late 16th and 17th centuries, the figure of the indigene or "savage"—and later, increasingly, the "good savage"—was held up as a reproach to European civilization, then in the throes of the French Wars of Religion and Thirty Years' War. During the St. Bartholomew's Day massacre (1572), some ten to twenty thousand men, women, and children were massacred by Catholic mobs, chiefly in Paris, but also throughout France. This horrifying breakdown of civil control was deeply disturbing to thoughtful people on both sides of the religious divide.

Foremost among the atrocities connected with the religious conflict was the St. Batholomew's massacre (August 224, 1572) ... The Parisian populace [was] inflamed by anti-Protestant preaching, and a general massacre ensued, devastating the Huguenot community of Paris. Bodies were stripped naked, mutilated, and thrown into the Seine. The massacres spread throughout France into the fall of 1572, spreading as far as Bordeaux [home of Montaigne]. ... Estimates of the total number of deaths vary widely; modern historians tend to accept the approximate number of ten thousand. ... Huguenots were not entirely innocent of massacres themselvesIn his famous essay "Of Cannibals" (1580), Michel de Montaigne—himself a Catholic—reported that the Tupinambá people of Brazil ceremoniously eat the bodies of their dead enemies as a matter of honour. However, he reminded his readers that Europeans behave even more barbarously when they burn each other alive for disagreeing about religion (he implies): "One calls 'barbarism' whatever he is not accustomed to."

— Ullrich Langer, "Montaigne's political and religious context", in The Cambridge Companion to Montaigne

The cannibal practices are admitted [by Montaigne] but presented as part of a complex and balanced set of customs and beliefs which "make sense" in their own right. They are attached to a powerfully positive morality of valor and pride, one that would have been likely to appeal to early modern codes of honor, and they are contrasted with modes of behavior in the France of the wars of religion which appear as distinctly less attractive, such as torture and barbarous methods of execution (...)In "Of Cannibals", Montaigne uses cultural (but not moral) relativism for the purpose of satire. His cannibals are neither noble nor especially good, but not worse than 16th-century Europeans. In this classical humanist view, customs differ but people everywhere are prone to cruelty, a quality that Montaigne detested.

In his Essais ... Montaigne discussed the first three wars of religion (1562–63; 1567–68; 1568–70) quite specifically; he had personally participated in them, on the side of the royal army, in southwestern France. The St. Bartholomew's Day massacre led him to retire to his lands in the Périgord region, and remain silent on all public affairs until the 1580s. Thus, it seems that he was traumatized by the massacre. To him, cruelty was a criterion that differentiated the Wars of Religion from previous conflicts, which he idealized. Montaigne considered that three factors accounted for the shift from regular war to the carnage of civil war: popular intervention, religious demagogy and the never-ending aspect of the conflict..... He chose to depict cruelty through the image of hunting, which fitted with the tradition of condemning hunting for its association with blood and death, but it was still quite surprising, to the extent that this practice was part of the aristocratic way of life. Montaigne reviled hunting by describing it as an urban massacre scene. In addition, the man-animal relationship allowed him to define virtue, which he presented as the opposite of cruelty. … [as] a sort of natural benevolence based on ... personal feelings. … Montaigne associated the propensity to cruelty toward animals, with that exercised toward men. After all, following the St. Bartholomew's Day massacre, the invented image of Charles IX shooting Huguenots from the Louvre palace window did combine the established reputation of the king as a hunter, with a stigmatization of hunting, a cruel and perverted custom, did it not?The treatment of indigenous peoples by the Spanish Conquistadors also produced a great deal of bad conscience and recriminations. The Spanish priest Bartolomé de las Casas, who witnessed it, may have been the first to idealize the simple life of the indigenous Americans. He and other observers praised their simple manners and reported that they were incapable of lying.

— David El Kenz, Massacres During the Wars of Religion

European angst over colonialism inspired fictional treatments such as Aphra Behn's novel Oroonoko, or the Royal Slave (1688), about a slave revolt in Surinam in the West Indies. Behn's story was not primarily a protest against slavery; rather, it was written for money, and it met readers' expectations by following the conventions of the European romance novella. The leader of the revolt, Oroonoko, is truly noble in that he is a hereditary African prince, and he laments his lost African homeland in the traditional terms of a classical Golden Age. He is not a savage but dresses and behaves like a European aristocrat. Behn's story was adapted for the stage by Irish playwright Thomas Southerne, who stressed its sentimental aspects, and as time went on, it came to be seen as addressing the issues of slavery and colonialism, remaining very popular throughout the 18th century.

Origin of term

In English, the phrase Noble Savage first appeared in poet John Dryden's heroic play, The Conquest of Granada (1672):The hero who speaks these words in Dryden's play is here denying the right of a prince to put him to death, on the grounds that he is not that prince's subject. These lines were quoted by Scott as the heading to Chapter 22 of his "A Legend of Montrose" (1819). "Savage" is better taken here in the sense of "wild beast", so that the phrase "noble savage" is to be read as a witty conceit meaning simply the beast that is above the other beasts, or man.I am as free as nature first made man,

Ere the base laws of servitude began,

When wild in woods the noble savage ran.

Ethnomusicologist Ter Ellingson believes that Dryden had picked up the expression "noble savage" from a 1609 travelogue about Canada by the French explorer Marc Lescarbot, in which there was a chapter with the ironic heading: "The Savages are Truly Noble", meaning simply that they enjoyed the right to hunt game, a privilege in France granted only to hereditary aristocrats. It is not known if Lescarbot was aware of Montaigne's stigmatization of the aristocratic pastime of hunting, though some authors believe he was familiar with Montaigne. Lescarbot's familiarity with Montaigne, is discussed by Ter Ellingson in The Myth of the Noble Savage.

In Dryden's day the word "savage" did not necessarily have the connotations of cruelty now associated with it. Instead, as an adjective, it could as easily mean "wild", as in a wild flower, for example. Thus he wrote in 1697, 'the savage cherry grows. ...'

One scholar, Audrey Smedley, believes that: "English conceptions of 'the savage' were grounded in expansionist conflicts with Irish pastoralists and more broadly, in isolation from, and denigration of neighboring European peoples." and Ellingson agrees that "The ethnographic literature lends considerable support for such arguments."

In France the stock figure that in English is called the "noble savage" has always been simply "le bon sauvage", "the good wild man", a term without any of the paradoxical frisson of the English one. Montaigne is generally credited for being at the origin of this myth in his Essays (1580), especially "Of Coaches" and "Of Cannibals". This character, an idealized portrayal of "Nature's Gentleman", was an aspect of 18th-century sentimentalism, along with other stock characters such as, the Virtuous Milkmaid, the Servant-More-Clever-than-the-Master (such as Sancho Panza and Figaro, among countless others), and the general theme of virtue in the lowly born. The use of stock characters (especially in theater) to express moral truths derives from classical antiquity and goes back to Theophrastus's Characters, a work that enjoyed a great vogue in the 17th and 18th centuries and was translated by Jean de La Bruyère. The practice largely died out with advent of 19th-century realism but lasted much longer in genre literature, such as adventure stories, Westerns, and, arguably, science fiction. Nature's Gentleman, whether European-born or exotic, takes his place in this cast of characters, along with the Wise Egyptian, Persian, and Chinaman. "But now, alongside the Good Savage, the Wise Egyptian claims his place." Some of these types are discussed by Paul Hazard in The European Mind.

He had always existed, from the time of the Epic of Gilgamesh, where he appears as Enkiddu, the wild-but-good man who lives with animals. Another instance is the untutored-but-noble medieval knight, Parsifal. The Biblical shepherd boy David falls into this category. The association of virtue with withdrawal from society—and specifically from cities—was a familiar theme in religious literature.

Hayy ibn Yaqdhan an Islamic philosophical tale (or thought experiment) by Ibn Tufail from 12th-century Andalusia, straddles the divide between the religious and the secular. The tale is of interest because it was known to the New England Puritan divine, Cotton Mather. Translated into English (from Latin) in 1686 and 1708, it tells the story of Hayy, a wild child, raised by a gazelle, without human contact, on a deserted island in the Indian Ocean. Purely through the use of his reason, Hayy goes through all the gradations of knowledge before emerging into human society, where he revealed to be a believer of natural religion, which Cotton Mather, as a Christian Divine, identified with Primitive Christianity. The figure of Hayy is both a Natural man and a Wise Persian, but not a Noble Savage.

The locus classicus of the 18th-century portrayal of the American Indian are the famous lines from Alexander Pope's "Essay on Man" (1734):

Lo, the poor Indian! whose untutor'd mindTo Pope, writing in 1734, the Indian was a purely abstract figure— "poor" either meant ironically, or applied because he was uneducated and a heathen, but also happy because he was living close to Nature. This view reflects the typical Age of Reason belief that men are everywhere and in all times the same as well as a Deistic conception of natural religion (although Pope, like Dryden, was Catholic). Pope's phrase, "Lo the Poor Indian", became almost as famous as Dryden's "noble savage" and, in the 19th century, when more people began to have first hand knowledge of and conflict with the Indians, would be used derisively for similar sarcastic effect.

Sees God in clouds, or hears him in the wind;

His soul proud Science never taught to stray

Far as the solar walk or milky way;

Yet simple Nature to his hope has giv'n,

Behind the cloud-topp'd hill, a humbler heav'n;

Some safer world in depth of woods embrac'd,

Some happier island in the wat'ry waste,

Where slaves once more their native land behold,

No fiends torment, no Christians thirst for gold!

To be, contents his natural desire;

He asks no angel's wing, no seraph's fire:

But thinks, admitted to that equal sky,

His faithful dog shall bear him company.

Attributes of romantic primitivism

On our arrival upon this coast we found there a savage race who ... lived by hunting and by the fruits which the trees spontaneously produced. These people ... were greatly surprised and alarmed by the sight of our ships and arms and retired to the mountains. But since our soldiers were curious to see the country and hunt deer, they were met by some of these savage fugitives. The leaders of the savages accosted them thus: "We abandoned for you, the pleasant sea-coast, so that we have nothing left but these almost inaccessible mountains: at least it is just that you leave us in peace and liberty. Go, and never forget that you owe your lives to our feeling of humanity. Never forget that it was from a people whom you call rude and savage that you receive this lesson in gentleness and generosity. ... We abhor that brutality which, under the gaudy names of ambition and glory, ... sheds the blood of men who are all brothers. ... We value health, frugality, liberty, and vigor of body and mind: the love of virtue, the fear of the gods, a natural goodness toward our neighbors, attachment to our friends, fidelity to all the world, moderation in prosperity, fortitude in adversity, courage always bold to speak the truth, and abhorrence of flattery. ... If the offended gods so far blind you as to make you reject peace, you will find, when it is too late, that the people who are moderate and lovers of peace are the most formidable in war.In the 1st century AD, sterling qualities such as those enumerated above by Fénelon (excepting perhaps belief in the brotherhood of man) had been attributed by Tacitus in his Germania to the German barbarians, in pointed contrast to the softened, Romanized Gauls. By inference Tacitus was criticizing his own Roman culture for getting away from its roots—which was the perennial function of such comparisons. Tacitus's Germans did not inhabit a "Golden Age" of ease but were tough and inured to hardship, qualities which he saw as preferable to the decadent softness of civilized life. In antiquity this form of "hard primitivism", whether admired or deplored (both attitudes were common), co-existed in rhetorical opposition to the "soft primitivism" of visions of a lost Golden Age of ease and plenty.

— Fénelon, The Adventures of Telemachus (1699)

As art historian Erwin Panofsky explains:

There had been, from the beginning of classical speculation, two contrasting opinions about the natural state of man, each of them, of course, a "Gegen-Konstruktion" to the conditions under which it was formed. One view, termed "soft" primitivism in an illuminating book by Lovejoy and Boas, conceives of primitive life as a golden age of plenty, innocence, and happiness—in other words, as civilized life purged of its vices. The other, "hard" form of primitivism conceives of primitive life as an almost subhuman existence full of terrible hardships and devoid of all comforts—in other words, as civilized life stripped of its virtues.In the 18th century the debates about primitivism centered around the examples of the people of Scotland as often as the American Indians. The rude ways of the Highlanders were often scorned, but their toughness also called forth a degree of admiration among "hard" primitivists, just as that of the Spartans and the Germans had done in antiquity. One Scottish writer described his Highland countrymen this way:

— Erwin Panofsky, art historian

They greatly excel the Lowlanders in all the exercises that require agility; they are incredibly abstemious, and patient of hunger and fatigue; so steeled against the weather, that in traveling, even when the ground is covered with snow, they never look for a house, or any other shelter but their plaid, in which they wrap themselves up, and go to sleep under the cope of heaven. Such people, in quality of soldiers, must be invincible ...

Reaction to Hobbes

Debates about "soft" and "hard" primitivism intensified with the publication in 1651 of Hobbes's Leviathan (or Commonwealth), a justification of absolute monarchy. Hobbes, a "hard Primitivist", flatly asserted that life in a state of nature was "solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short"—a "war of all against all":Whatsoever therefore is consequent to a time of Warre, where every man is Enemy to every man; the same is consequent to the time, wherein men live without other security, than what their own strength, and their own invention shall furnish them withall. In such condition, there is no place for Industry; because the fruit thereof is uncertain; and consequently no Culture of the Earth; no Navigation, nor use of the commodities that may be imported by Sea; no commodious Building; no Instruments of moving, and removing such things as require much force; no Knowledge of the face of the Earth; no account of Time; no Arts; no Letters; no Society; and which is worst of all, continuall feare, and danger of violent death; And the life of man, solitary, poore, nasty, brutish, and shortReacting to the wars of religion of his own time and the previous century, he maintained that the absolute rule of a king was the only possible alternative to the otherwise inevitable violence and disorder of civil war. Hobbes' hard primitivism may have been as venerable as the tradition of soft primitivism, but his use of it was new. He used it to argue that the state was founded on a social contract in which men voluntarily gave up their liberty in return for the peace and security provided by total surrender to an absolute ruler, whose legitimacy stemmed from the Social Contract and not from God.

— Hobbes

Hobbes' vision of the natural depravity of man inspired fervent disagreement among those who opposed absolute government. His most influential and effective opponent in the last decade of the 17th century was Shaftesbury. Shaftesbury countered that, contrary to Hobbes, humans in a state of nature were neither good nor bad, but that they possessed a moral sense based on the emotion of sympathy, and that this emotion was the source and foundation of human goodness and benevolence. Like his contemporaries (all of whom who were educated by reading classical authors such as Livy, Cicero, and Horace), Shaftesbury admired the simplicity of life of classical antiquity. He urged a would-be author “to search for that simplicity of manners, and innocence of behavior, which has been often known among mere savages; ere they were corrupted by our commerce” (Advice to an Author, Part III.iii). Shaftesbury's denial of the innate depravity of man was taken up by contemporaries such as the popular Irish essayist Richard Steele (1672–1729), who attributed the corruption of contemporary manners to false education. Influenced by Shaftesbury and his followers, 18th-century readers, particularly in England, were swept up by the cult of Sensibility that grew up around Shaftesbury's concepts of sympathy and benevolence.

Meanwhile, in France, where those who criticized government or Church authority could be imprisoned without trial or hope of appeal, primitivism was used primarily as a way to protest the repressive rule of Louis XIV and XV, while avoiding censorship. Thus, in the beginning of the 18th century, a French travel writer, the Baron de Lahontan, who had actually lived among the Huron Indians, put potentially dangerously radical Deist and egalitarian arguments in the mouth of a Canadian Indian, Adario, who was perhaps the most striking and significant figure of the "good" (or "noble") savage, as we understand it now, to make his appearance on the historical stage:

Adario sings the praises of Natural Religion. ... As against society he puts forward a sort of primitive Communism, of which the certain fruits are Justice and a happy life. ... He looks with compassion on poor civilized man—no courage, no strength, incapable of providing himself with food and shelter: a degenerate, a moral cretin, a figure of fun in his blue coat, his red hose, his black hat, his white plume and his green ribands. He never really lives because he is always torturing the life out of himself to clutch at wealth and honors which, even if he wins them, will prove to be but glittering illusions. ... For science and the arts are but the parents of corruption. The Savage obeys the will of Nature, his kindly mother, therefore he is happy. It is civilized folk who are the real barbarians.Published in Holland, Lahontan's writings, with their controversial attacks on established religion and social customs, were immensely popular. Over twenty editions were issued between 1703 and 1741, including editions in French, English, Dutch and German.

— Paul Hazard, The European Mind

Interest in the remote peoples of the earth, in the unfamiliar civilizations of the East, in the untutored races of America and Africa, was vivid in France in the 18th century. Everyone knows how Voltaire and Montesquieu used Hurons or Persians to hold up the glass to Western manners and morals, as Tacitus used the Germans to criticize the society of Rome. But very few ever look into the seven volumes of the Abbé Raynal’s History of the Two Indies, which appeared in 1772. It is however one of the most remarkable books of the century. Its immediate practical importance lay in the array of facts which it furnished to the friends of humanity in the movement against negro slavery. But it was also an effective attack on the Church and the sacerdotal system. ... Raynal brought home to the conscience of Europeans the miseries which had befallen the natives of the New World through the Christian conquerors and their priests. He was not indeed an enthusiastic preacher of Progress. He was unable to decide between the comparative advantages of the savage state of nature and the most highly cultivated society. But he observes that “the human race is what we wish to make it", that the felicity of man depends entirely on the improvement of legislation, and ... his view is generally optimistic.

— J.B. Bury, The Idea of Progress: an Inquiry into its Origins and Growth

Atala au tombeau, by Girodet, 1808 – Musée du Louvre.

Many of the most incendiary passages in Raynal's book, one of the bestsellers of the eighteenth century, especially in the Western Hemisphere, are now known to have been in fact written by Diderot. Reviewing Jonathan Israel's Democratic Enlightenment: Philosophy, Revolution, and Human Rights, Jeremy Jennings, notes that The History of the Two Indies, in the opinion of Jonathan Israel, was the text that "made a world revolution" by delivering "the most devastating single blow to the existing order":

Usually (and incorrectly) attributed to the pen of the Abbé Raynal, its ostensible theme of Europe's colonial expansion allowed Diderot not only to depict the atrocities and greed of colonialism but also to develop an argument in defense of universal human rights, equality, and a life free from tyranny and fanaticism. More widely read than any other work of the Enlightenment ... it summoned people to understand the causes of their misery and then to revolt.In the later 18th century, the published voyages of Captain James Cook and Louis Antoine de Bougainville seemed to open a glimpse into an unspoiled Edenic culture that still existed in the un-Christianized South Seas. Their popularity inspired Diderot's Supplement to the Voyage of Bougainville (1772), a scathing critique of European sexual hypocrisy and colonial exploitation.

— Jeremy Jennings, Reason's Revenge: How a small group of radical philosophers made a world revolution and lost control of it to 'Rouseauist fanatics', Times Literary Supplement

Benjamin Franklin's Remarks Concerning the Savages of North America

The Care and Labour of providing for Artificial and Fashionable Wants, the sight of so many rich wallowing in Superfluous plenty, whereby so many are kept poor and distressed for Want, the Insolence of Office ... and restraints of Custom, all contrive to disgust [the Indians] with what we call civil Society.Benjamin Franklin, who had negotiated with the Indians during the French and Indian War, protested vehemently against the Paxton massacre that took place at Conestoga, in western Pennsylvania, of December 1763, in which white vigilantes massacred Indian women and children, many of whom had converted to Christianity. Franklin himself personally organized a Quaker militia to control the white population and "strengthen the government". In his pamphlet Remarks Concerning the Savages of North America (1784), Franklin deplored the use of the term "savages" for Native Americans:

— Benjamin Franklin, marginalia in a pamphlet entitled [Matthew Wheelock], Reflections, Moral and Political on Great Britain and Her Colonies, 1770

Savages we call them, because their manners differ from ours, which we think the perfection of civility; they think the same of theirs.Franklin used the massacres to illustrate his point that no race had a monopoly on virtue, likening the Paxton vigilantes to "Christian White Savages'". Franklin cried out to a just God to punish those who carried the Bible in one hand and the hatchet in the other: 'O ye unhappy Perpetrators of this Horrid Wickedness!'" Franklin praised the Indian way of life, their customs of hospitality, their councils, which reached agreement by discussion and consensus, and noted that many white men had voluntarily given up the purported advantages of civilization to live among them, but that the opposite was rare.

Franklin's writings on American Indians were remarkably free of ethnocentricism, although he often used words such as "savages," which carry more prejudicial connotations in the twentieth century than in his time. Franklin's cultural relativism was perhaps one of the purest expressions of Enlightenment assumptions that stressed racial equality and the universality of moral sense among peoples. Systematic racism was not called into service until a rapidly expanding frontier demanded that enemies be dehumanized during the rapid, historically inevitable westward movement of the nineteenth century. Franklin's respect for cultural diversity did not reappear widely as an assumption in Euro-American thought until Franz Boas and others revived it around the end of the nineteenth century. Franklin's writings on Indians express the fascination of the Enlightenment with nature, the natural origins of man and society, and natural (or human) rights. They are likewise imbued with a search (which amounted at times almost to a ransacking of the past) for alternatives to monarchy as a form of government, and to orthodox state-recognized churches as a form of worship.Though retrospectively it may seem to us that Franklin may have idealized the Indians to make a rhetorical point, the phrase "noble savage" never appears in his writings.

— Bruce E. Johansen, Forgotten Founders: Benjamin Franklin, the Iroquois, and the Rationale for the American Revolution

Erroneous identification of Rousseau with the noble savage

Jean-Jacques Rousseau, like Shaftesbury, also insisted that man was born with the potential for goodness; and he, too, argued that civilization, with its envy and self-consciousness, has made men bad. In his Discourse on the Origins of Inequality Among Men (1754), Rousseau maintained that man in a State of Nature had been a solitary, ape-like creature, who was not méchant (bad), as Hobbes had maintained, but (like some other animals) had an "innate repugnance to see others of his kind suffer" (and this natural sympathy constituted the Natural Man's one-and-only natural virtue). It was Rousseau's fellow philosophe, Voltaire, objecting to Rousseau's egalitarianism, who charged him with primitivism and accused him of wanting to make people go back and walk on all fours. Because Rousseau was the preferred philosopher of the radical Jacobins of the French Revolution, he, above all, became tarred with the accusation of promoting the notion of the "noble savage", especially during the polemics about Imperialism and scientific racism in the last half of the 19th century. Yet the phrase "noble savage" does not occur in any of Rousseau's writings. In fact, Rousseau arguably shared Hobbes' pessimistic view of humankind, except that as Rousseau saw it, Hobbes had made the error of assigning it to too early a stage in human evolution. According to the historian of ideas, Arthur O. Lovejoy:The notion that Rousseau’s Discourse on Inequality was essentially a glorification of the State of Nature, and that its influence tended to wholly or chiefly to promote "Primitivism" is one of the most persistent historical errors.In his Discourse on the Origins of Inequality, Rousseau, anticipating the language of Darwin, states that as the animal-like human species increased there arose a "formidable struggle for existence" between it and other species for food. It was then, under the pressure of necessity, that le caractère spécifique de l'espèce humaine—the specific quality that distinguished man from the beasts—emerged—intelligence, a power, meager at first but yet capable of an "almost unlimited development". Rousseau calls this power the faculté de se perfectionner—perfectibility. Man invented tools, discovered fire, and in short, began to emerge from the state of nature. Yet at this stage, men also began to compare himself to others: "It is easy to see. ... that all our labors are directed upon two objects only, namely, for oneself, the commodities of life, and consideration on the part of others." Amour propre—the desire for consideration (self regard), Rousseau calls a "factitious feeling arising, only in society, which leads a man to think more highly of himself than of any other." This passion began to show itself with the first moment of human self-consciousness, which was also that of the first step of human progress: "It is this desire for reputation, honors, and preferment which devours us all ... this rage to be distinguished, that we own what is best and worst in men—our virtues and our vices, our sciences and our errors, our conquerors and our philosophers—in short, a vast number of evil things and a small number of good." It is this "which inspires men to all the evils which they inflict upon one another.". To be sure, Rousseau praises the newly discovered "savage" tribes (whom Rousseau does not consider in a "state of nature"), as living a life that is simpler and more egalitarian than that of the Europeans; and he sometimes praises this "third stage" it in terms that could be confused with the romantic primitivism fashionable in his times. He also identifies ancient primitive communism under a patriarchy, such as he believes characterized the "youth" of mankind, as perhaps the happiest state and perhaps also illustrative of how man was intended by God to live. But these stages are not all good, but rather are mixtures of good and bad. According to Lovejoy, Rousseau's basic view of human nature after the emergence of social living is basically identical to that of Hobbes. Moreover, Rousseau does not believe that it is possible or desirable to go back to a primitive state. It is only by acting together in civil society and binding themselves to its laws that men become men; and only a properly constituted society and reformed system of education could make men good. According to Lovejoy:

— A. O. Lovejoy, The Supposed Primitivism of Rousseau’s Discourse on Inequality (1923).

For Rousseau, man's good lay in departing from his "natural" state—but not too much; "perfectability" up to a certain point was desirable, though beyond that point an evil. Not its infancy but its jeunesse [youth] was the best age of the human race. The distinction may seem to us slight enough; but in the mid-eighteenth century it amounted to an abandonment of the stronghold of the primitivistic position. Nor was this the whole of the difference. As compared with the then-conventional pictures of the savage state, Rousseau's account even of this third stage is far less idyllic; and it is so because of his fundamentally unfavorable view of human nature quâ human. ... His savages are quite unlike Dryden's Indians: "Guiltless men, that danced away their time, / Fresh as the groves and happy as their clime—" or Mrs. Aphra Behn's natives of Surinam, who represented an absolute idea of the first state of innocence, "before men knew how to sin." The men in Rousseau's "nascent society" already had 'bien des querelles et des combats [many quarrels and fights]'; l'amour propre was already manifest in them ... and slights or affronts were consequently visited with vengeances terribles.For Rousseau the remedy was not in going back to the primitive but in reorganizing society on the basis of a properly drawn up social compact, so as to "draw from the very evil from which we suffer [i.e., civilization and progress] the remedy which shall cure it." Lovejoy concludes that Rousseau's doctrine, as expressed in his Discourse on Inequality:

declares that there is a dual process going on through history; on the one hand, an indefinite progress in all those powers and achievements which express merely the potency of man's intellect; on the other hand, an increasing estrangement of men from one another, an intensification of ill-will and mutual fear, culminating in a monstrous epoch of universal conflict and mutual destruction [i.e., the fourth stage in which we now find ourselves]. And the chief cause of the latter process Rousseau, following Hobbes and Mandeville, found, as we have seen, in that unique passion of the self-conscious animal – pride, self esteem, le besoin de se mettre au dessus des autres ["the need to put oneself above others"]. A large survey of history does not belie these generalizations, and the history of the period since Rousseau wrote lends them a melancholy verisimilitude. Precisely the two processes, which he described have ... been going on upon a scale beyond all precedent: immense progress in man's knowledge and in his powers over nature, and at the same time a steady increase of rivalries, distrust, hatred and at last "the most horrible state of war" ... [Moreover Rousseau] failed to realize fully how strongly amour propre tended to assume a collective form ... in pride of race, of nationality, of class.

19th century belief in progress and the fall of the natural man

During the 19th century the idea that men were everywhere and always the same that had characterized both classical antiquity and the Enlightenment was exchanged for a more organic and dynamic evolutionary concept of human history. Advances in technology now made the indigenous man and his simpler way of life appear, not only inferior, but also, even his defenders agreed, foredoomed by the inexorable advance of progress to inevitable extinction. The sentimentalized "primitive" ceased to figure as a moral reproach to the decadence of the effete European, as in previous centuries. Instead, the argument shifted to a discussion of whether his demise should be considered a desirable or regrettable eventuality. As the century progressed, native peoples and their traditions increasingly became a foil serving to highlight the accomplishments of Europe and the expansion of the European Imperial powers, who justified their policies on the basis of a presumed racial and cultural superiority.Charles Dickens 1853 article on "The Noble Savage" in Household Words

In 1853 Charles Dickens wrote a scathingly sarcastic review in his weekly magazine Household Words of painter George Catlin's show of American Indians when it visited England. In his essay, entitled "The Noble Savage", Dickens expressed repugnance for Indians and their way of life in no uncertain terms, recommending that they ought to be “civilised off the face of the earth”. (Dickens's essay refers back to Dryden's well-known use of the term, not to Rousseau.) Dickens's scorn for those unnamed individuals, who, like Catlin, he alleged, misguidedly exalted the so-called "noble savage", was limitless. In reality, Dickens maintained, Indians were dirty, cruel, and constantly fighting among themselves. Dickens's satire on Catlin and others like him who might find something to admire in the American Indians or African bushmen is a notable turning point in the history of the use of the phrase.Like others who would henceforth write about the topic, Dickens begins by disclaiming a belief in the "noble savage":

To come to the point at once, I beg to say that I have not the least belief in the Noble Savage. I consider him a prodigious nuisance and an enormous superstition. ... I don't care what he calls me. I call him a savage, and I call a savage a something highly desirable to be civilized off the face of the earth.... The noble savage sets a king to reign over him, to whom he submits his life and limbs without a murmur or question and whose whole life is passed chin deep in a lake of blood; but who, after killing incessantly, is in his turn killed by his relations and friends the moment a grey hair appears on his head. All the noble savage's wars with his fellow-savages (and he takes no pleasure in anything else) are wars of extermination—which is the best thing I know of him, and the most comfortable to my mind when I look at him. He has no moral feelings of any kind, sort, or description; and his "mission" may be summed up as simply diabolical.Dickens' essay was arguably a pose of manly, no-nonsense realism and a defense of Christianity. At the end of it his tone becomes more recognizably humanitarian, as he maintains that, although the virtues of the savage are mythical and his way of life inferior and doomed, he still deserves to be treated no differently than if he were an Englishman of genius, such as Newton or Shakespeare:

— Charles Dickens

To conclude as I began. My position is, that if we have anything to learn from the Noble Savage, it is what to avoid. His virtues are a fable; his happiness is a delusion; his nobility, nonsense. We have no greater justification for being cruel to the miserable object, than for being cruel to a WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE or an ISAAC NEWTON; but he passes away before an immeasurably better and higher power [i.e., that of Christianity] than ever ran wild in any earthly woods, and the world will be all the better when this place knows him no more.

— Charles Dickens

Scapegoating the Inuit: cannibalism and Sir John Franklin's lost expedition

Although Charles Dickens had ridiculed positive depictions of Native Americans as portrayals of so-called "noble" savages, he made an exception (at least initially) in the case of the Inuit, whom he called “loving children of the north”, “forever happy with their lot,” “whether they are hungry or full”, and “gentle loving savages”, who, despite a tendency to steal, have a “quiet, amiable character” ("Our Phantom Ship on an Antediluvian Cruise", Household Words, April 16, 1851). However he soon reversed this rosy assessment, when on October 23, 1854, The Times of London published a report by explorer-physician John Rae of the discovery by Eskimos of the remains of the lost Franklin expedition along with unmistakable evidence of cannibalism among members of the party:From the mutilated state of many of the corpses and the contents of the kettles, it is evident that our wretched countrymen had been driven to the last resource—cannibalism—as a means of prolonging existence.Franklin's widow and other surviving relatives and indeed the nation as a whole were shocked to the core and refused to accept these reports, which appeared to undermine the whole assumption of the cultural superiority of the heroic white explorer-scientist and the imperial project generally. Instead, they attacked the reliability of the Eskimos who had made the gruesome discovery and called them liars. An editorial in The Times called for further investigation:

to arrive at a more satisfactory conclusion with regard to the fate of poor Franklin and his friends . ... Is the story told by the Esquimaux the true one? Like all savages they are liars, and certainly would not scruple at the utterance of any falsehood which might, in their opinion, shield them from the vengeance of the white man."This line was energetically taken up by Dickens, who wrote in his weekly magazine:

It is impossible to form an estimate of the character of any race of savages from their deferential behavior to the white man while he is strong. The mistake has been made again and again; and the moment the white man has appeared in the new aspect of being weaker than the savage, the savage has changed and sprung upon him. There are pious persons who, in their practice, with a strange inconsistency, claim for every child born to civilization all innate depravity, and for every child born to the woods and wilds all innate virtue. We believe every savage to be in his heart covetous, treacherous, and cruel; and we have yet to learn what knowledge the white man—lost, houseless, shipless, apparently forgotten by his race, plainly famine-stricken, weak frozen, helpless, and dying—has of the gentleness of the Esquimaux nature.Dr. John Rae rebutted Dickens in two articles in Household Words: “The Lost Arctic Voyagers”, Household Words, No. 248 (December 23, 1854), and "Dr. Rae’s Report to the Secretary of the Admiralty", Household Words, No. 249 (December 30, 1854). Though he did not call them noble, Dr. Rae, who had lived among the Inuit, defended them as “dutiful” and “a bright example to the most civilized people”, comparing them favorably with the undisciplined crew of the Franklin expedition, whom he suggested were ill-treated and "would have mutinied under privation", and moreover with the lower classes in England or Scotland generally.

— Charles Dickens, The Lost Arctic Voyagers, Household Words, December 2, 1854.

Dickens and Wilkie Collins subsequently collaborated on a melodramatic play, "The Frozen Deep", about the menace of cannibalism in the far north, in which "the villainous role assigned to the Eskimos in Household Words is assumed by a working class Scotswoman.

The Frozen Deep was performed as a benefit organized by Dickens and attended by Queen Victoria, Prince Albert, and Emperor Leopold II of Belgium, among others, to fund a memorial to the Franklin Expedition. (Dr. Rae himself was Scots).

Rae's respect for the Inuit and his refusal to scapegoat them in the Franklin affair arguably harmed his career. Lady Franklin's campaign to glorify the dead of her husband's expedition, aided and abetted by Dickens, resulted in his being more or less shunned by the British establishment. Although it was not Franklin but Rae who in 1848 discovered the last link in the much-sought-after Northwest Passage, Rae was never awarded a knighthood and died in obscurity in London. (In comparison fellow Scot and contemporary explorer David Livingstone was knighted and buried with full imperial honors in Westminster Abbey). However, modern historians have confirmed Rae's discovery of the Northwest Passage and the accuracy of his report on cannibalism among Franklin's crew. Canadian author Ken McGoogan, a specialist on Arctic exploration, states that Rae's willingness to learn and adopt the ways of indigenous Arctic peoples made him stand out as the foremost specialist of his time in cold-climate survival and travel. Rae's respect for Inuit customs, traditions, and skills was contrary to the prejudiced belief of many 19th-century Europeans that native peoples had no valuable technical knowledge or information to impart.

In July 2004, Orkney and Shetland MP Alistair Carmichael introduced into the UK Parliament a motion proposing that the House "regrets that Dr Rae was never awarded the public recognition that was his due". In March 2009 Carmichael introduced a further motion urging Parliament to formally state it "regrets that memorials to Sir John Franklin outside the Admiralty headquarters and inside Westminster Abbey still inaccurately describe Franklin as the first to discover the [North West] passage, and calls on the Ministry of Defence and the Abbey authorities to take the necessary steps to clarify the true position."

Dickens's racism, like that of many Englishmen, became markedly worse after the Sepoy Rebellion of 1857 in India.

The cruelties of the Sepoy natives [toward the whites] have inflamed the nation to a degree unprecedented within my memory. Peace Societies, Aborigines Protection Societies, and societies for the reformation of criminals are silent. There is one cry for revenge.It was said that Dickens's racism, “grew progressively more illiberal over the course of his career". Grace Moore, on the other hand, argues that Dickens, a staunch abolitionist and opponent of imperialism, had views on racial matters that were a good deal more complex than previous critics have suggested. This event, and the virtually contemporaneous occurrence of the American Civil War (1861–1864), which threatened to, and then did, put an end to slavery, coincided with a polarization of attitudes exemplified by the phenomenon of scientific racism.

— Thomas Babington Macaulay, Diary

Scientific racism

In 1860, John Crawfurd and James Hunt mounted a defense of British imperialism based on "scientific racism". Crawfurd, in alliance with Hunt, took over the presidency of the Ethnological Society of London, which was an offshoot of the Aborigines' Protection Society, founded with the mission to defend indigenous peoples against slavery and colonial exploitation. Invoking "science" and "realism", the two men derided their "philanthropic" predecessors for believing in human equality and for not recognizing that mankind was divided into superior and inferior races. Crawfurd, who opposed Darwinian evolution, "denied any unity to mankind, insisting on immutable, hereditary, and timeless differences in racial character, principal amongst which was the 'very great' difference in 'intellectual capacity.'" For Crawfurd, the races had been created separately and were different species. Crawfurd was Scots, and thought the Scots "race" superior to all others; whilst Hunt, on the other hand, believed in the supremacy of the Anglo-Saxon "race". Crawfurd and Hunt routinely accused those who disagreed with them of believing in "Rousseau's Noble Savage". The pair ultimately quarreled because Hunt believed in slavery and Crawfurd did not. "As Ter Ellingson demonstrates, Crawfurd was responsible for re-introducing the Pre-Rousseauian concept of 'the Noble Savage' to modern anthropology, attributing it wrongly and quite deliberately to Rousseau.”. In an otherwise rather lukewarm review of Ellingson's book in Journal of Colonialism and Colonial History 4:1 (Spring 2003), Frederick E. Hoxie writes:For early modern scholars from [St. Thomas] More to Rousseau, descriptions of Indian cultures could provide opportunities to criticize “civilization.” After Hunt and Crawfurd—or at least at about the middle of the 19th century, when both imperial ambition and racial ideology was hardening into national policy in Europe and the U.S.—Indians became foils of a different kind: people whose traditions underscored the accomplishments of Europe. The imperial powers were now the models of human achievement. Ellingson sees this shift and shows us how profoundly it affected popular conceptions of Native people."If Rousseau was not the inventor of the Noble Savage, who was?" writes Ellingson,

— Frederick E. Hoxie

One who turns for help to [Hoxie Neale] Fairchild's 1928 study, a compendium of citations from romantic writings on the "savage" may be surprised to find [his book] The Noble Savage almost completely lacking in references to its nominal subject. That is, although Fairchild assembles hundreds of quotations from ethnographers, philosophers, novelists, poets, and playwrights from the 17th century to the 19th century, showing a rich variety of ways in which writers romanticized and idealized those who Europeans considered "savages", almost none of them explicitly refer to something called the "Noble Savage". Although the words, always duly capitalized, appear on nearly every page, it turns out that in every instance, with four possible exceptions, they are Fairchild's words and not those of the authors cited.Ellingson finds that any remotely positive portrayal of an indigenous (or working class) person is apt to be characterized (out of context) as a supposedly "unrealistic" or "romanticized" "Noble Savage". He points out that Fairchild even includes as an example of a supposed "Noble Savage", a picture of a Negro slave on his knees, lamenting lost his freedom. According to Ellingson, Fairchild ends his book with a denunciation of the (always unnamed) believers in primitivism or "The Noble Savage"—who, he feels, are threatening to unleash the dark forces of irrationality on civilization.

Ellingson argues that the term "noble savage", an oxymoron, is a derogatory one, which those who oppose "soft" or romantic primitivism use to discredit (and intimidate) their supposed opponents, whose romantic beliefs they feel are somehow threatening to civilization. Ellingson maintains that virtually none of those accused of believing in the "noble savage" ever actually did so. He likens the practice of accusing anthropologists (and other writers and artists) of belief in the noble savage to a secularized version of the inquisition, and he maintains that modern anthropologists have internalized these accusations to the point where they feel they have to begin by ritualistically disavowing any belief in "noble savage" if they wish to attain credibility in their fields. He notes that text books with a painting of a handsome Native American (such as the one by Benjamin West on this page) are even given to school children with the cautionary caption, "A painting of a Noble Savage". West's depiction is characterized as a typical "noble savage" by art historian Vivien Green Fryd, but her interpretation has been contested.

Opponents of primitivism

The most famous modern example of "hard" (or anti-) primitivism in books and movies was William Golding's Lord of the Flies, published in 1954. The title is said to be a reference to the Biblical devil, Beelzebub. This book, in which a group of school boys stranded on a desert island "revert" to savage behavior, was a staple of high school and college required reading lists during the Cold War.In the 1970s, film director Stanley Kubrick professed his opposition to primitivism. Like Dickens, he began with a disclaimer:

Man isn't a noble savage, he's an ignoble savage. He is irrational, brutal, weak, silly, unable to be objective about anything where his own interests are involved—that about sums it up. I'm interested in the brutal and violent nature of man because it's a true picture of him. And any attempt to create social institutions on a false view of the nature of man is probably doomed to failure.The opening scene of Kubrick's movie 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) depicted prehistoric ape-like men wielding weapons of war, as the tools that supposedly lifted them out of their animal state and made them human.

Another opponent of primitivism is the Australian anthropologist Roger Sandall, who has accused other anthropologists of exalting the "noble savage". A third is archeologist Lawrence H. Keeley, who has criticised a "widespread myth" that "civilized humans have fallen from grace from a simple primeval happiness, a peaceful golden age" by uncovering archeological evidence that he claims demonstrates that violence prevailed in the earliest human societies. Keeley argues that the "noble savage" paradigm has warped anthropological literature to political ends.

The noble savage is described as having a natural existence. The term ignoble savage has an obvious negative connotation. The ignoble savage is detested—described as having a cruel and primitive existence. Often, the phrase “ignoble savage” was used and abused to justify colonialism. The concept of the ignoble savage gave Europeans the "right" to establish colonies without considering the possibility of preexisting, functional societies. A prime example would be the use of the Discovery Doctrine which is still used in the courts of the United States of America.