Social cognitive neuroscience is the scientific study of the biological processes underpinning social cognition. Specifically, it uses the tools of neuroscience to study "the mental mechanisms that create, frame, regulate, and respond to our experience of the social world". Social cognitive neuroscience uses the epistemological foundations of cognitive neuroscience, and is closely related to social neuroscience. Social cognitive neuroscience employs human neuroimaging, typically using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI). Human brain stimulation techniques such as transcranial magnetic stimulation and transcranial direct-current stimulation are also used. In nonhuman animals, direct electrophysiological recordings and electrical stimulation of single cells and neuronal populations are utilized for investigating lower-level social cognitive processes.

History and methods

The first scholarly works about the neural bases of social cognition can be traced back to Phineas Gage, a man who survived a traumatic brain injury in 1849 and was extensively studied for resultant changes in social functioning and personality. In 1924, esteemed psychologist Gordon Allport wrote a chapter on the neural bases of social phenomenon in his textbook of social psychology.

However, these works did not generate much activity in the decades that

followed. The beginning of modern social cognitive neuroscience can be

traced to Michael Gazzaniga's book, Social Brain (1985), which attributed cerebral lateralization

to the peculiarities of social psychological phenomenon. Isolated

pockets of social cognitive neuroscience research emerged in the late

1980s to the mid-1990s, mostly using single-unit electrophysiological recordings in nonhuman primates or neuropsychological lesion studies in humans.

During this time, the closely related field of social neuroscience

emerged in parallel, however it mostly focused on how social factors

influenced autonomic, neuroendocrine, and immune systems. In 1996, Giacomo Rizzolatti's group made one of the most seminal discoveries in social cognitive neuroscience: the existence of mirror neurons in macaque frontoparietal cortex. The mid-1990s saw the emergence of functional positron emission tomography

(PET) for humans, which enabled the neuroscientific study of abstract

(and perhaps uniquely human) social cognitive functions such as theory of mind and mentalizing. However, PET is prohibitively expensive and requires the ingestion of radioactive tracers, thus limiting its adoption.

In the year 2000, the term social cognitive neuroscience was coined by Matthew Lieberman and Kevin Oschner, who are from social and cognitive psychology

backgrounds, respectively. This was done to integrate and brand the

isolated labs doing research on the neural bases of social cognition. Also in the year 2000, Elizabeth Phelps and colleagues published the first fMRI study on social cognition, specifically on race evaluations.

The adoption of fMRI, a less expensive and noninvasive neuroimaging

modality, induced explosive growth in the field. In 2001, the first academic conference on social cognitive neuroscience was held at University of California, Los Angeles. The mid-2000s saw the emergence of academic societies related to the field (Social and Affective Neuroscience Society, Society for Social Neuroscience), as well as peer-reviewed journals specialized for the field (Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, Social Neuroscience).

In the 2000s and beyond, labs conducting social cognitive neuroscience

research proliferated throughout Europe, North America, East Asia,

Australasia, and South America.

Starting in the late 2000s, the field began expand its

methodological repertoire by incorporating other neuroimaging modalities

(e.g. electroencephalography, magnetoencephalography, functional near-infared spectroscopy), advanced computational methods (e.g. multivariate pattern analysis, causal modeling, graph theory), and brain stimulation techniques (e.g. transcranial magnetic stimulation, transcranial direct-current stimulation, deep brain stimulation).

Due to the volume and rigor of research in the field, the 2010s saw

social cognitive neuroscience achieving mainstream acceptance in the

wider fields of neuroscience and psychology.

Functional anatomy

Much of social cognition is primarily subserved by two dissociable macro-scale brain networks: the mirror neuron system (MNS) and default mode network

(DMN). MNS is thought to represent and identify observable actions

(e.g. reaching for a cup) that are used by DMN to infer unobservable

mental states, traits, and intentions (e.g. thirsty). Concordantly, the activation onset of MNS has been shown to precede DMN during social cognition. However, the extent of feedforward, feedback, and recurrent

processing within and between MNS and DMN is not yet

well-characterized, thus it is difficult to fully dissociate the exact

functions of the two networks and their nodes.

Mirror neuron system (MNS)

Mirror neurons, first discovered in macaque frontoparietal cortex, fire when actions are either performed or observed.

In humans, similar sensorimotor "mirroring" responses have been found

in the brain regions listed below, which are collectively referred to as

MNS. The MNS is has been found to identify and represent intentional actions such as facial expressions, body language, and grasping. MNS may encode the concept

of an action, not just the sensory and motor information associated

with an action. As such, MNS representations have been shown to be

invariant of how an action is observed (e.g. sensory modality) and how

an action is performed (e.g. left versus right hand, upwards or

downwards). MNS has even been found to represent actions that are described in written language.

Mechanistic theories of MNS functioning fall broadly into two

camps: motor and cognitive theories. Classical motor theories claim that

abstract action representations arise from simulating actions within

the motor system, while newer cognitive theories propose that abstract

action representations arise from the integration of multiple domains of

information: perceptual, motor, semantic, and conceptual.

Aside from these competing theories, there are more fundamental

controversies surrounding the human MNS – even the very existence of

mirror neurons in this network is debated.

As such, the term "MNS" is sometimes eschewed for more functionally

defined names such as "action observation network", "action

identification network", and "action representation network".

Premotor cortex

The macaque premotor cortex was the location of the first discoveries of mirror neurons.

The premotor cortex is associated with a diverse array of functions,

encompassing low-level motor control, motor planning, sensory guidance

of movement, along with higher level cognitive functions such as language processing and action comprehension. The premotor cortex has been found to contain subregions with unique cytoarchitectural properties, the significance of which is not yet fully understood. In humans, sensorimotor mirroring responses are also found throughout premotor cortex and adjacent sections of inferior frontal gyrus and supplementary motor area.

Visuospatial information is more prevalent in ventral premotor cortex than dorsal premotor cortex.

In humans, sensorimotor mirroring responses extend beyond ventral

premotor cortex into adjacent regions of inferior frontal gyrus,

including Broca's area, an area that is critical to language processing and speech production.

Action representations in inferior frontal gyrus can be evoked by

language, such as action verbs, in addition to the observed and

performed actions typically used as stimuli in biological motion

studies.

The overlap between language and action understanding processes in

inferior frontal gyrus has spurred some researchers to suggest

overlapping neurocomputational mechanisms between the two.

Dorsal premotor cortex is strongly associated with motor preparation

and guidance, such as representing multiple motor choices and deciding

the final selection of action.

Intraparietal sulcus

Classical studies of action observation have found mirror neurons in macaque intraparietal sulcus.

In humans, sensorimotor mirroring responses are centered around the

anterior intraperietal sulcus, with responses also seen in adjacent

regions such as inferior parietal lobule and superior parietal lobule.

Intraparietal sulcus has been shown to more sensitive to the motor

features of biological motion, relative to semantic features.

Intraparietal sulcus has been shown to encode magnitude in a

domain-general manner, whether it be the magnitude of a motor movement,

or the magnitude of a person's social status. Intraparietal sulcus is considered a part of the dorsal visual stream,

but is also thought to receive inputs from non-dorsal stream regions

such as lateral occipitotemporal cortex and posterior superior temporal

sulcus.

Lateral occipitotemporal cortex (LOTC)

LOTC encompasses lateral regions of the visual cortex such as V5 and extrastriate body area.

Though LOTC is typically associated with visual processing,

sensorimotor mirroring responses and abstract action representations are

reliably found in this region.

LOTC includes cortical areas that are sensitive to motion, objects,

body parts, kinematics, body postures, observed movements, and semantic

content in verbs. LOTC is thought to encode the fine sensorimotor details of an observed action (e.g. local kinematic and perceptual features). LOTC is also thought to bind together the different means by which a specific action can be carried out.

Default mode network (DMN)

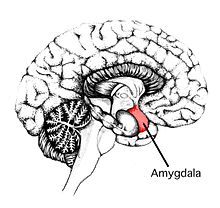

The default mode network (DMN) is thought to process and represent abstract social information, such as mental states, traits, and intentions. Social cognitive functions such as theory of mind, mentalizing, emotion recognition, empathy, moral cognition, and social working memory

consistently recruit DMN regions in human neuroimaging studies. Though

the functional anatomy of these functions can differ, they often include

the core DMN hubs of medial prefrontal cortex, posterior cingulate, and

temporoparietal junction. Aside from social cognition, the DMN is broadly associated with internally directed cognition. The DMN has been found to be involved in memory-related processing (semantic, episodic, prospection), self-related processing (e.g. introspection), and mindwandering.

Unlike studies of the mirror neuron system, task-based DMN

investigations almost always use human subjects, as DMN-related social

cognitive functions are rudimentary or difficult to measure in

nonhumans.

However, much of DMN activity occurs during rest, as DMN activation and

connectivity are quickly engaged and sustained during the absence of

goal-directed cognition. As such, the DMN is widely thought the subserve the "default mode" of mammalian brain function.

The interrelations between social cognition, rest, and the

diverse array of DMN-related functions are not yet well understood and

is a topic of active research. Social, non-social, and spontaneous

processes in the DMN are thought to share at least some underlying

neurocomputational mechanisms with each other.

Medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC)

Medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC) is strongly associated with abstract social cognition such as mentalizing and theory of mind. Mentalizing about others activates much of the mPFC, but dorsal mPFC appears to be more selective for information about other people, while the middle mPFC may be more selective for information about the self.

Ventral regions of mPFC, such as ventromedial prefrontal cortex and medial orbitofrontal cortex, are thought to play a critical role in the affective

components of social cognition. For example, ventromedial prefrontal

cortex has been found to represent affective information about other

people. Ventral mPFC has been shown to be critical in the computation and representation of valence and value for many types of stimuli, not just social stimuli.

The mPFC may subserve the most abstract components of social

cognition, as it is one of the most domain general brain regions, sits

at the top of the cortical hierarchy, and is last to activate during

DMN-related tasks.

Posterior cingulate cortex (PCC)

Abstract social cognition recruits a large area of posteromedial cortex centered around posterior cingulate cortex (PCC), but also extending into precuneus and retrosplenial cortex. The specific function of PCC in social cognition is not yet well characterized, and its role may be generalized and tightly linked with medial prefrontal cortex. One view is that PCC may help represent some visuospatial and semantic components of social cognition.

Additionally, PCC may track social dynamics by facilitating bottom-up

attention to behaviorally relevant sources of information in the

external environment and in memory. Dorsal PCC is also linked to monitoring behaviorally relevant changes in the environment, perhaps aiding in social navigation.

Outside of the social domain, PCC is associated with a very diverse

array of functions, such as attention, memory, semantics, visual

processing, mindwandering, consciousness, cognitive flexibility, and

mediating interactions between brain networks.

Temporoparietal junction (TPJ)

The temporoparietal junction (TPJ) is thought to be critical to distinguishing between multiple agents, such as the self and other.

The right TPJ is robustly activated by false belief tasks, in which

subjects have to distinguish between others' beliefs and their own

beliefs in a given situation. The TPJ is also recruited by the wide variety of abstract social cognitive tasks associated with the DMN.

Outside of the social domain, TPJ is associated with a diverse array of

functions such as attentional reorienting, target detection, contextual

updating, language processing, and episodic memory retrieval. The social and non-social functions of the TPJ may share common neurocomputational mechanisms.

For example, the substrates of attentional reorientation in TPJ may be

used for reorienting attention between the self and others, and for

attributing attention between social agents. Moreover, a common neural encoding mechanism has been found to instantiate social, temporal, and spatial distance in TPJ.

Superior temporal sulcus (STS)

Social tasks recruit areas of lateral temporal cortex centered around superior temporal sulcus (STS), but also extending to superior temporal gyrus, middle temporal gyrus, and the temporal poles.

During social cognition, the anterior STS and temporal poles are

strongly associated with abstract social cognition and person

information, while the posterior STS is most associated with social vision and biological motion processing. The posterior STS is also thought to provide perceptual inputs to the mirror neuron system.

Other regions

There

are also several brain regions that fall outside the MNS and DMN which

are strongly associated with certain social cognitive functions.

Ventrolateral prefrontal cortex (VLPFC)

The ventrolateral prefrontal cortex (VLPFC) is associated with emotional and inhibitory processing. It has been found to be involved in emotion recognition from facial expressions, body language, prosody, and more. Specifically, it is thought to access semantic representations of emotional constructs during emotion recognition.

Moreover, VLPFC is often recruited in empathy, mentalizing, and theory

of mind tasks. VLPFC is thought to support the inhibition of

self-perspective when thinking about other people.

Insula

The insula is critical to emotional processing and interoception.

It has been found to be involved in emotion recognition, empathy,

morality, and social pain. The anterior insula is thought to facilitate

feeling the emotions of others, especially negative emotions such as

vicarious pain. Lesions of the insula are associated with decreased

empathy capacity. Anterior insula also activates during social pain,

such as the pain caused by social rejection.

Anterior cingulate cortex (ACC)

The anterior cingulate cortex

(ACC) is associated with emotional processing and error monitoring. The

dorsal ACC appears to share some social cognitive functions to the

anterior insula, such as facilitating feeling the emotions of others,

especially negative emotions. The dorsal ACC also robustly activates

during social pain, like the pain caused by being the victim of an

injustice. The dorsal ACC is also associated with social evaluation,

such as the detection and appraisal of social exclusion. The subgenual ACC has been found to activate for vicarious reward, and may be involved in prosocial behavior.

Fusiform face area (FFA)

The fusiform face area

(FFA) is strongly associated with face processing and perceptual

expertise. The FFA has been shown to process the visuospatial features

of faces, and may also encode some semantic features of faces.