Guru (/ˈɡuːruː/, UK also /ˈɡʊruː, ˈɡʊər-/; Sanskrit: गुरु, IAST: guru; Pali: garu) is a Sanskrit term for a "mentor, guide, expert, or master" of certain knowledge or field. In pan-Indian traditions, a guru is more than a teacher. In Sanskrit, guru means literally dispeller of darkness. Traditionally, the guru is a reverential figure to the disciple (or chela in Sanskrit) or student, with the guru serving as a "counselor, who helps mold values, shares experiential knowledge as much as literal knowledge, an exemplar in life, an inspirational source and who helps in the spiritual evolution of a student". Whatever language it is written in, Judith Simmer-Brown explains that a tantric spiritual text is often codified in an obscure twilight language so that it cannot be understood by anyone without the verbal explanation of a qualified teacher, the guru. A guru is also one's spiritual guide, who helps one to discover the same potentialities that the guru has already realized.

The oldest references to the concept of guru are found in the earliest Vedic texts of Hinduism. The guru, and gurukula – a school run by guru, were an established tradition in India by the 1st millennium BCE, and these helped compose and transmit the various Vedas, the Upanishads, texts of various schools of Hindu philosophy, and post-Vedic Shastras ranging from spiritual knowledge to various arts. By about mid 1st millennium CE, archaeological and epigraphical evidence suggest numerous larger institutions of gurus existed in India, some near Hindu temples, where guru-shishya tradition helped preserve, create and transmit various fields of knowledge. These gurus led broad ranges of studies including Hindu scriptures, Buddhist texts, grammar, philosophy, martial arts, music and painting.

The tradition of the guru is also found in Jainism, referring to a spiritual preceptor, a role typically served by a Jain ascetic. In Sikhism, the guru tradition has played a key role since its founding in the 15th century, its founder is referred to as Guru Nanak, and its scripture as Guru Granth Sahib. The guru concept has thrived in Vajrayāna Buddhism, where the tantric guru is considered a figure to worship and whose instructions should never be violated.

In the Western world, the term is sometimes used in a derogatory way to refer to individuals who have allegedly exploited their followers' naiveté, particularly in certain cults or groups in the fields of hippie, new religious movements, self-help and tantra.

Definition and etymology

The word guru (Sanskrit: गुरु), a noun, connotes "teacher" in Sanskrit, but in ancient Indian traditions it has contextual meanings with significance beyond what teacher means in English. The guru is more than someone who teaches specific type of knowledge, and includes in its scope someone who is also a "counselor, a sort of parent of mind and soul, who helps mold values and experiential knowledge as much as specific knowledge, an exemplar in life, an inspirational source and who reveals the meaning of life." The word has the same meaning in other languages derived from or borrowing words from Sanskrit, such as Hindi, Marathi, Punjabi, Tamil, Telugu, Kannada, Malayalam, Odia, Bengali, Gujarati and Nepali. The Malayalam term Acharyan or Asan is derived from the Sanskrit word Acharya.

As a noun the word means the imparter of knowledge (jñāna; also Pali: ñāna). As an adjective, it means 'heavy,' or 'weighty,' in the sense of "heavy with knowledge," heavy with spiritual wisdom, "heavy with spiritual weight," "heavy with the good qualities of scriptures and realization," or "heavy with a wealth of knowledge." The word has its roots in the Sanskrit gri (to invoke, or to praise), and may have a connection to the word gur, meaning 'to raise, lift up, or to make an effort'.

Sanskrit guru is cognate with Latin gravis 'heavy; grave, weighty, serious' and Greek βαρύς barus 'heavy'. All three derive from the Proto-Indo-European root *gʷerə-, specifically from the zero-grade form *gʷr̥ə-.

Female equivalent of gurus are called gurvis. The wife of the guru is the guru patni or guru ma. The guru's son is guru putra, while the guru's daughter is the guru putri.

Darkness and light

गुशब्दस्त्वन्धकारः स्यात् रुशब्दस्तन्निरोधकः।

अन्धकारनिरोधित्वात् गुरुरित्यभिधीयते॥ १६॥

The syllable gu means darkness, the syllable ru, he who dispels them,

Because of the power to dispel darkness, the guru is thus named.— Advayataraka Upanishad, Verse 16

A popular etymological theory considers the term "guru" to be based on the syllables gu (गु) and ru (रु), which it claims stands for darkness and "light that dispels it", respectively. The guru is seen as the one who "dispels the darkness of ignorance."

Reender Kranenborg disagrees, stating that darkness and light have nothing to do with the word guru. He describes this as a folk etymology.

Joel Mlecko states, "Gu means ignorance, and Ru means dispeller," with guru meaning the one who "dispels ignorance, all kinds of ignorance", ranging from spiritual to skills such as dancing, music, sports and others. Karen Pechelis states that, in the popular parlance, the "dispeller of darkness, one who points the way" definition for guru is common in the Indian tradition.

In Western Esotericism and the Science of Religion, Pierre Riffard makes a distinction between "occult" and "scientific" etymologies, citing as an example of the former the etymology of 'guru' in which the derivation is presented as gu ("darkness") and ru ('to push away'); the latter he exemplifies by "guru" with the meaning of 'heavy'.

In Hinduism

Scriptures

The word Guru is mentioned in the earliest layer of Vedic texts. The hymn 4.5.6 of Rigveda, for example, states Joel Mlecko, describes the guru as, "the source and inspirer of the knowledge of the Self, the essence of reality," for one who seeks.

The Upanishads, that is the later layers of the Vedic text, mention guru. Chandogya Upanishad, in chapter 4.4 for example, declares that it is only through guru that one attains the knowledge that matters, the insights that lead to Self-knowledge. The Katha Upanisad, in verse 1.2.8 declares the guru as indispensable to the acquisition of knowledge. In chapter 3 of Taittiriya Upanishad, human knowledge is described as that which connects the teacher and the student through the medium of exposition, just like a child is the connecting link between the father and the mother through the medium of procreation. In the Taittiriya Upanishad, the guru then urges a student, states Mlecko, to "struggle, discover and experience the Truth, which is the source, stay and end of the universe."

The ancient tradition of reverence for the guru in Hindu scriptures is apparent in 6.23 of the Shvetashvatara Upanishad, which equates the need of reverence and devotion for guru to be the same as for god,

यस्य देवे परा भक्तिः यथा देवे तथा गुरौ ।

तस्यैते कथिता ह्यर्थाः प्रकाशन्ते महात्मनः ॥ २३ ॥

He who has highest Bhakti (love, devotion) of Deva (god),

just like his Deva, so for his Guru,

To him who is high-minded,

these teachings will be illuminating.— Shvetashvatara Upanishad 6.23

The Bhagavad Gita is a dialogue where Krishna speaks to Arjuna of the role of a guru, and similarly emphasizes in verse 4.34 that those who know their subject well are eager for good students, and the student can learn from such a guru through reverence, service, effort and the process of inquiry.

Capabilities, role and methods for helping a student

The 8th century Hindu text Upadesasahasri of the Advaita Vedanta philosopher Adi Shankara discusses the role of the guru in assessing and guiding students. In Chapter 1, he states that teacher is the pilot as the student walks in the journey of knowledge, he is the raft as the student rows. The text describes the need, role and characteristics of a teacher, as follows,

When the teacher finds from signs that knowledge has not been grasped or has been wrongly grasped by the student, he should remove the causes of non-comprehension in the student. This includes the student's past and present knowledge, want of previous knowledge of what constitutes subjects of discrimination and rules of reasoning, behavior such as unrestrained conduct and speech, courting popularity, vanity of his parentage, ethical flaws that are means contrary to those causes. The teacher must enjoin means in the student that are enjoined by the Śruti and Smrti, such as avoidance of anger, Yamas consisting of Ahimsa and others, also the rules of conduct that are not inconsistent with knowledge. He [teacher] should also thoroughly impress upon the student qualities like humility, which are the means to knowledge.

— Adi Shankara, Upadesha Sahasri 1.4-1.5

The teacher is one who is endowed with the power of furnishing arguments pro and con, of understanding questions [of the student], and remembers them. The teacher possesses tranquility, self-control, compassion and a desire to help others, who is versed in the Śruti texts (Vedas, Upanishads), and unattached to pleasures here and hereafter, knows the subject and is established in that knowledge. He is never a transgressor of the rules of conduct, devoid of weaknesses such as ostentation, pride, deceit, cunning, jugglery, jealousy, falsehood, egotism and attachment. The teacher's sole aim is to help others and a desire to impart the knowledge.

— Adi Shankara, Upadesha Sahasri 1.6

Adi Shankara presents a series of examples wherein he asserts that the best way to guide a student is not to give immediate answers, but posit dialogue-driven questions that enable the student to discover and understand the answer.

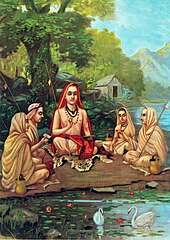

Gurukula and the guru-shishya tradition

Traditionally, the Guru would live a simple married life, and accept shishya (student, Sanskrit: शिष्य) where he lived. A person would begin a life of study in the Gurukula (the household of the Guru). The process of acceptance included proffering firewood and sometimes a gift to the guru, signifying that the student wants to live with, work and help the guru in maintaining the gurukul, and as an expression of a desire for education in return over several years. At the Gurukul, the working student would study the basic traditional vedic sciences and various practical skills-oriented sastras along with the religious texts contained within the Vedas and Upanishads. The education stage of a youth with a guru was referred to as Brahmacharya, and in some parts of India this followed the Upanayana or Vidyarambha rites of passage.

The gurukul would be a hut in a forest, or it was, in some cases, a monastery, called a matha or ashram or sampradaya in different parts of India. These had a lineage of gurus, who would study and focus on certain schools of Hindu philosophy or trade, and these were known as guru-shishya parampara (teacher-student tradition). This guru-driven tradition included arts such as sculpture, poetry and music.

Inscriptions from 4th century CE suggest the existence of gurukuls around Hindu temples, called Ghatikas or Mathas, where the Vedas were studied. In south India, 9th century Vedic schools attached to Hindu temples were called Calai or Salai, and these provided free boarding and lodging to students and scholars. Archaeological and epigraphical evidence suggests that ancient and medieval era gurukuls near Hindu temples offered wide range of studies, ranging from Hindu scriptures to Buddhist texts, grammar, philosophy, martial arts, music and painting.

The Guru (teacher) Shishya (disciple) parampara or guru parampara, occurs where the knowledge (in any field) is passed down through the succeeding generations. It is the traditional, residential form of education, where the Shishya remains and learns with his Guru as a family member. The fields of study in traditional guru-sisya parampara were diverse, ranging from Hindu philosophy, martial arts, music, dance to various Vedangas.

Gender and caste

The Hindu texts offer a conflicting view of whether access to guru and education was limited to men and to certain varna (castes). The Vedas and the Upanishads never mention any restrictions based either on gender or on varna. The Yajurveda and Atharvaveda texts state that knowledge is for everyone, and offer examples of women and people from all segments of society who are guru and participated in vedic studies. The Upanishads assert that one's birth does not determine one's eligibility for spiritual knowledge, only one's effort and sincerity matters.

In theory, the early Dharma-sutras and Dharma-sastras, such as Paraskara Grhyasutra, Gautama Smriti and Yajnavalkya smriti, state all four varnas are eligible to all fields of knowledge; while verses of Manusmriti state that Vedic study is available only to men of three varnas, unavailable to Shudra and women. In practice, state Stella Kramrisch and others, the guru tradition and availability of education extended to all segments of ancient and medieval society. Lise McKean states the guru concept has been prevalent over the range of class and caste backgrounds, and the disciples a guru attracts come from both genders and a range of classes and castes. During the bhakti movement of Hinduism, which started in about mid 1st millennium CE, the gurus included women and members of all varna.

Attributes

The Advayataraka Upanishad states that the true teacher is a master in the field of knowledge, well-versed in the Vedas, is free from envy, knows yoga, lives a simple life that of a yogi, has realized the knowledge of the Atman (Soul, Self). Some scriptures and gurus have warned against false teachers, and have recommended that the spiritual seeker test the guru before accepting him. Swami Vivekananda said that there are many incompetent gurus, and that a true guru should understand the spirit of the scriptures, have a pure character and be free from sin, and should be selfless, without desire for money and fame.

According to the Indologist Georg Feuerstein, in some traditions of Hinduism, when one reaches the state of Self-knowledge, one's own soul becomes the guru. In Tantra, states Feuerstein, the guru is the "ferry who leads one across the ocean of existence." A true guru guides and counsels a student's spiritual development because, states Yoga-Bija, endless logic and grammar leads to confusion, and not contentment. However, various Hindu texts caution prudence and diligence in finding the right guru, and avoiding the wrong ones. For example, in Kula-Arnava text states the following guidance:

Gurus are as numerous as lamps in every house. But, O-Goddess, difficult to find is a guru who lights up everything like a sun.

Gurus who are proficient in the Vedas, textbooks and so on are numerous. But, O Goddess, difficult to find is a guru who is proficient in the supreme Truth.

Gurus who rob their disciples of their wealth are numerous. But, O Goddess, difficult to find is a guru who removes the disciples' suffering.

Numerous here on earth are those who are intent on social class, stage of life and family. But he who is devoid of all concerns is a guru difficult to find.

An intelligent man should choose a guru by whom supreme Bliss is attained, and only such a guru and none other.— Kula-Arnava, 13.104 - 13.110, Translated by Georg Feuerstein

A true guru is, asserts Kula-Arnava, one who lives the simple virtuous life he preaches, is stable and firm in his knowledge, master yogi with the knowledge of Self (soul) and Brahman (ultimate reality). The guru is one who initiates, transmits, guides, illuminates, debates and corrects a student in the journey of knowledge and of self-realization. The attribute of the successful guru is to help make the disciple into another guru, one who transcends him, and becomes a guru unto himself, driven by inner spirituality and principles.

In modern Hinduism

In modern neo-Hinduism, Kranenborg states guru may refer to entirely different concepts, such as a spiritual advisor, or someone who performs traditional rituals outside a temple, or an enlightened master in the field of tantra or yoga or eastern arts who derives his authority from his experience, or a reference by a group of devotees of a sect to someone considered a god-like Avatar by the sect.

The tradition of reverence for guru continues in several denominations within modern Hinduism, but he or she is typically never considered as a prophet, but one who points the way to spirituality, Oneness of being, and meaning in life.

In Buddhism

In Vajrayana Buddhism's Tantric teachings, the rituals require the guidance of a guru. The guru is considered essential and to the Buddhist devotee, the guru is the "enlightened teacher and ritual master", states Stephen Berkwitz. The guru is known as the vajra guru (literally "diamond guru"). Initiations or ritual empowerments are necessary before the student is permitted to practice a particular tantra, in Vajrayana Buddhist sects found in Tibet and South Asia. The tantras state that the guru is equivalent to Buddha, states Berkwitz, and is a figure to worship and whose instructions should never be violated.

The guru is the Buddha, the guru is the Dhamma, and the guru is the Sangha. The guru is the glorious Vajradhara, in this life only the guru is the means [to awakening]. Therefore, someone wishing to attain the state of Buddhahood should please the guru.

— Guhyasanaya Sadhanamala 28, 12th-century

There are Four Kinds of Lama (Guru) or spiritual teacher (Tib. lama nampa shyi) in Tibetan Buddhism:

- gangzak gyüpé lama — the individual teacher who is the holder of the lineage

- gyalwa ka yi lama — the teacher which is the word of the buddhas

- nangwa da yi lama — the symbolic teacher of all appearances

- rigpa dön gyi lama — the absolute teacher, which is rigpa, the true nature of mind

In various Buddhist traditions, there are equivalent words for guru, which include Shastri (teacher), Kalyana Mitra (friendly guide, Pali: Kalyāṇa-mittatā), Acarya (master), and Vajra-Acarya (hierophant). The guru is literally understood as "weighty", states Alex Wayman, and it refers to the Buddhist tendency to increase the weight of canons and scriptures with their spiritual studies. In Mahayana Buddhism, a term for Buddha is Bhaisajya guru, which refers to "medicine guru", or "a doctor who cures suffering with the medicine of his teachings".

In Jainism

Guru is the spiritual preceptor in Jainism, and typically a role served by Jain ascetics. The guru is one of three fundamental tattva (categories), the other two being dharma (teachings) and deva (divinity). The guru-tattva is what leads a lay person to the other two tattva. In some communities of the Śvētāmbara sect of Jainism, a traditional system of guru-disciple lineage exists.

The guru is revered in Jainism ritually with Guru-vandan or Guru-upashti, where respect and offerings are made to the guru, and the guru sprinkles a small amount of vaskep (a scented powder mixture of sandalwood, saffron, and camphor) on the devotee's head with a mantra or blessings.

In Sikhism

In Sikhism, Guru is the source of all knowledge which is Almighty. In Chopai Sahib, Guru Gobind Singh states about who is the Guru:

ਜਵਨ ਕਾਲ ਜੋਗੀ ਸ਼ਿਵ ਕੀਯੋ ॥ ਬੇਦ ਰਾਜ ਬ੍ਰਹਮਾ ਜੂ ਥੀਯੋ ॥ |

The Temporal Lord, who created Shiva, the Yogi; who created Brahma, the Master of the Vedas; |

| —Dasam Granth, 384-385 |

|

The Sikh gurus were fundamental to the Sikh religion, however the concept in Sikhism differs from other usages. Sikhism is derived from the Sanskrit word shishya, or disciple and is all about the relationship between the teacher and a student. The concept of Guru in Sikhism stands on two pillars i.e. Miri-Piri. 'Piri' means spiritual authority and 'Miri' means temporal authority. Traditionally, the concept of Guru is considered central in Sikhism, and its main scripture is prefixed as a Guru, called Guru Granth Sahib, the words therein called Gurbani.

In Western culture

As an alternative to established religions, some people in Europe and the US looked to spiritual guides and gurus from India and other countries. Gurus from many denominations traveled to Western Europe and the US and established followings.

In particular during the 1960s and 1970s many gurus acquired groups of young followers in Western Europe and the US. According to the American sociologist David G. Bromley this was partially due to the repeal of the Chinese Exclusion Act in 1965 which permitted Asian gurus entrance to the US. According to the Dutch Indologist Albertina Nugteren, the repeal was only one of several factors and a minor one compared with the two most important causes for the surge of all things 'Eastern': the post-war cross-cultural mobility and the general dissatisfaction with established Western values.

According to the professor in sociology Stephen A. Kent at the University of Alberta and Kranenborg (1974), one of the reasons why in the 1970s young people including hippies turned to gurus was because they found that drugs had opened for them the existence of the transcendental or because they wanted to get high without drugs. According to Kent, another reason why this happened so often in the US then, was because some anti-Vietnam War protesters and political activists became worn out or disillusioned of the possibilities to change society through political means, and as an alternative turned to religious means. One example of such group was the Hare Krishna movement (ISKCON) founded by A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada in 1966, many of whose followers voluntarily accepted the demanding lifestyle of bhakti yoga on a full-time basis, in stark contrast to much of the popular culture of the time.

Some gurus and the groups they lead attracted opposition from the Anti-Cult Movement. According to Kranenborg (1984), Jesus Christ fits the Hindu definition and characteristics of a guru.

Environmental activists are sometimes called "gurus" or "prophets" for embodying a moral or spiritual authority and gathering followers. Examples of environmental gurus are John Muir, Henry David Thoreau, Aldo Leopold, George Perkins Marsh, and David Attenborough. Abidin et al. wrote that environmental gurus "merge the boundaries" between spiritual and scientific authority.

Viewpoints

Gurus and the Guru-shishya tradition have been criticized and assessed by secular scholars, theologians, anti-cultists, skeptics, and religious philosophers.

- Jiddu Krishnamurti, groomed to be a world spiritual teacher by the leadership of the Theosophical Society in the early part of the 20th century, publicly renounced this role in 1929 while also denouncing the concept of gurus, spiritual leaders, and teachers, advocating instead the unmediated and direct investigation of reality.

- U. G. Krishnamurti, [no relation to Jiddu], sometimes characterized as a "spiritual anarchist", denied both the value of gurus and the existence of any related worthwhile "teaching".

- Dr. David C. Lane proposes a checklist consisting of seven points to assess gurus in his book, Exposing Cults: When the Skeptical Mind Confronts the Mystical. One of his points is that spiritual teachers should have high standards of moral conduct and that followers of gurus should interpret the behavior of a spiritual teacher by following Ockham's razor and by using common sense, and, should not naively use mystical explanations unnecessarily to explain immoral behavior. Another point Lane makes is that the bigger the claim a guru makes, such as the claim to be God, the bigger the chance is that the guru is unreliable. Dr. Lane's fifth point is that self-proclaimed gurus are likely to be more unreliable than gurus with a legitimate lineage.

- Highlighting what he sees as the difficulty in understanding the guru from Eastern tradition in Western society, Dr. Georg Feuerstein, a well-known German-American Indologist, writes in the article Understanding the Guru from his book The Deeper Dimension of Yoga: Theory and practice: "The traditional role of the guru, or spiritual teacher, is not widely understood in the West, even by those professing to practice Yoga or some other Eastern tradition entailing discipleship. [...] Spiritual teachers, by their very nature, swim against the stream of conventional values and pursuits. They are not interested in acquiring and accumulating material wealth or in competing in the marketplace, or in pleasing egos. They are not even about morality. Typically, their message is of a radical nature, asking that we live consciously, inspect our motives, transcend our egoic passions, overcome our intellectual blindness, live peacefully with our fellow humans, and, finally, realize the deepest core of human nature, the Spirit. For those wishing to devote their time and energy to the pursuit of conventional life, this kind of message is revolutionary, subversive, and profoundly disturbing". In his Encyclopedic Dictionary of Yoga (1990), Dr. Feuerstein writes that the importation of yoga to the West has raised questions as to the appropriateness of spiritual discipleship and the legitimacy of spiritual authority.

- A British professor of psychiatry, Anthony Storr, states in his book, Feet of Clay: A Study of Gurus, that he confines the word guru (translated by him as "revered teacher") to persons who have "special knowledge" who tell, referring to their special knowledge, how other people should lead their lives. He argues that gurus share common character traits (e.g. being loners) and that some suffer from a mild form of schizophrenia. He argues that gurus who are authoritarian, paranoid, eloquent, or who interfere in the private lives of their followers are the ones who are more likely to be unreliable and dangerous. Storr also refers to Eileen Barker's checklist to recognize false gurus. He contends that some so-called gurus claim special spiritual insights based on personal revelation, offering new ways of spiritual development and paths to salvation. Storr's criticism of gurus includes the possible risk that a guru may exploit his or her followers due to the authority that he or she may have over them, though Storr does acknowledge the existence of morally superior teachers who refrain from doing so. He holds the view that the idiosyncratic belief systems that some gurus promote were developed during a period of psychosis to make sense of their own minds and perceptions, and that these belief systems persist after the psychosis has gone. Storr notes that gurus generalize their experience to all people. Some of them believe that all humanity should accept their vision, while others teach that when the end of the world comes, only their followers will be saved, and the rest of the people will remain unredeemed. According to him, this ″apparently arrogant assumption″ is closely related and other characteristics of various gurus. Storr applies the term "guru" to figures as diverse as Jesus, Muhammad, Buddha, Gurdjieff, Rudolf Steiner, Carl Jung, Sigmund Freud, Jim Jones and David Koresh. The Belgian Indologist Koenraad Elst criticized Storr's book for its avoidance of the term prophet instead of guru for several people. Elst asserts that this is possibly due to Storr's pro-Western, pro-Christian cultural bias.

- Rob Preece, a psychotherapist and a practicing Buddhist, writes in The Noble Imperfection that while the teacher/disciple relationship can be an invaluable and fruitful experience, the process of relating to spiritual teachers also has its hazards. He writes that these potential hazards are the result of naiveté amongst Westerners as to the nature of the guru/devotee relationship, as well as a consequence of a lack of understanding on the part of Eastern teachers as to the nature of Western psychology. Preece introduces the notion of transference to explain the manner in which the guru/disciple relationship develops from a more Western psychological perspective. He writes: "In its simplest sense transference occurs when unconsciously a person endows another with an attribute that actually is projected from within themselves." In developing this concept, Preece writes that, when we transfer an inner quality onto another person, we may be giving that person a power over us as a consequence of the projection, carrying the potential for great insight and inspiration, but also the potential for great danger: "In giving this power over to someone else they have a certain hold and influence over us it is hard to resist, while we become enthralled or spellbound by the power of the archetype".

- According to a professor of religious studies at Dawson College in Quebec, Susan J. Palmer, the word guru has acquired very negative connotations in France.

- The psychiatrist Alexander Deutsch performed a long-term observation of a small cult, called The Family (not to be confused with Family International), founded by an American guru called Baba or Jeff in New York in 1972, who showed increasingly schizophrenic behavior. Deutsch observed that this man's mostly Jewish followers interpreted the guru's pathological mood swings as expressions of different Hindu deities and interpreted his behavior as holy madness, and his cruel deeds as punishments that they had earned. After the guru dissolved the cult in 1976, his mental condition was confirmed by Jeff's retrospective accounts to an author.

- Jan van der Lans (1933–2002), a professor of the psychology of religion at the Catholic University of Nijmegen, wrote, in a book commissioned by the Netherlands-based Catholic Study Center for Mental Health, about followers of gurus and the potential dangers that exist when personal contact between the guru and the disciple is absent, such as an increased chance of idealization of the guru by the student (myth making and deification), and an increase of the chance of false mysticism. He further argues that the deification of a guru is a traditional element of Eastern spirituality but, when detached from the Eastern cultural element and copied by Westerners, the distinction between the person who is the guru and that which he symbolizes is often lost, resulting in the relationship between the guru and disciple degenerating into a boundless, uncritical personality cult.

- In their 1993 book, The Guru Papers, authors Diana Alstad and Joel Kramer reject the guru-disciple tradition because of what they see as its structural defects. These defects include the authoritarian control of the guru over the disciple, which is in their view increased by the guru's encouragement of surrender to him. Alstad and Kramer assert that gurus are likely to be hypocrites because, in order to attract and maintain followers, gurus must present themselves as purer than and superior to ordinary people and other gurus.

- According to the journalist Sacha Kester, in a 2003 article in the Dutch newspaper De Volkskrant, finding a guru is a precarious matter, pointing to the many holy men in India and the case of Sathya Sai Baba whom Kester considers a swindler. In this article he also quotes the book Karma Cola describing that in this book a German economist tells author Gita Mehta, "It is my opinion that quality control has to be introduced for gurus. Many of my friends have become crazy in India". She describes a comment by Suranya Chakraverti who said that some Westerners do not believe in spirituality and ridicule a true guru. Other westerners, Chakraverti said, on the other hand believe in spirituality but tend to put faith in a guru who is a swindler.

- Teachings of Shri Satguru Devendra Ghia (Kaka) are in his hymns and the broadness of his thoughts is in the variety. "Religion is nothing but a path towards God. Different religions have evolved over different times and in different places based on the need of that era. However, the basic concept in each religion remains the same. Each religion talks of a universal God, who is eternal and infinite."