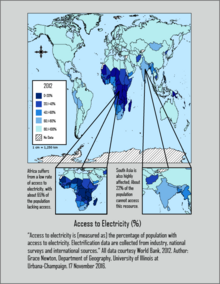

Energy poverty is lack of access to modern energy services. It refers to the situation of large numbers of people in developing countries and some people in developed countries whose well-being is negatively affected by very low consumption of energy, use of dirty or polluting fuels, and excessive time spent collecting fuel to meet basic needs. Today, 759 million people lack access to consistent electricity and 2.6 billion people use dangerous and inefficient cooking systems. It is inversely related to access to modern energy services, although improving access is only one factor in efforts to reduce energy poverty. Energy poverty is distinct from fuel poverty, which primarily focuses solely on the issue of affordability.

The term “energy poverty” came into emergence through the publication of Brenda Boardman’s book, Fuel Poverty: From Cold Homes to Affordable Warmth (1991). Naming the intersection of energy and poverty as “energy poverty” motivated the need to develop public policy to address energy poverty and also study its causes, symptoms, and effects in society. When energy poverty was first introduced in Boardman's book, energy poverty was described as not having enough power to heat and cool homes. Today, energy poverty is understood to be the result of complex systemic inequalities which create barriers to access modern energy at an affordable price. Energy poverty is challenging to measure and thus analyze because it is privately experienced within households, specific to cultural contexts, and dynamically changes depending on the time and space.

According to the Energy Poverty Action initiative of the World Economic Forum, "Access to energy is fundamental to improving quality of life and is a key imperative for economic development. In the developing world, energy poverty is still rife." As a result of this situation, the United Nations (UN) launched the Sustainable Energy for All Initiative and designated 2012 as the International Year for Sustainable Energy for All, which had a major focus on reducing energy poverty. The UN further recognizes the importance of energy poverty through Goal 7 of its Sustainable Development Goals to "ensure access to affordable, reliable, sustainable, and modern energy for all."

Causes

Energy sources

Rural areas are predominant in mostly developing countries, and the rural areas in the countries do not have modern energy infrastructure. They have heavily relied on traditional biomass such as wood fuel, charcoal, crop residual, wood pellets and the like. Because lack of modern energy infrastructure like power plants, transmission lines, underground pipelines to deliver energy resources such as natural gas, petroleum that need high or cutting-edge technologies and extremely high upfront costs, which are beyond their financial and technological capacity. Although some developing countries like BRIC have reached close to the energy-related technological level of developed countries and have financial power, still most developing countries are dominated by traditional biomass. According to the International Energy Agency IEA, "use of traditional biomass will decrease in many countries, but is likely to increase in South Asia and sub-Saharan Africa alongside population growth."

Energy poverty projects involving renewable sources can also make a positive contribution to low-carbon development strategies.

Energy price increases and poverty

Energy tariff increases are often important for environmental and fiscal reasons – though they can at times increase levels of household poverty. A 2016 study assesses the expected poverty and distributional effects of an energy price reform – in the context of Armenia; it estimates that a large natural gas tariff increase of about 40% contributed to an estimated 8% of households to substitute natural gas mainly with wood as their source of heating - and it also pushed an estimated 2.8% of households into poverty - i.e. below the national poverty line. This study also outlines the methodological and statistical assumptions and constraints that arise in estimating causal effects of energy reforms on household poverty, and also discusses possible effects of such reforms on non-monetary human welfare that is more difficult to measure statistically. A study 'High Energy', by Oldham.Jules,(2011) Scottish Council for Single Homeless, showed the difference between a new tenancy succeeding or failing when people moved on from homelessness, as a result of the new tenant having a) utilities in place before moving in, b) an understanding of payment options and meter types, and c) accessing the correct tariff to suit their budget and financial needs.

Energy Ladder

An energy ladder shows the improvement of energy use corresponding to an increase in the household income. Basically, as income increases, the energy types used by households would be cleaner and more efficient, but more expensive as moving from traditional biomass to electricity. "Households at lower levels of income and development tend to be at the bottom of the energy ladder, using fuel that is cheap and locally available but not very clean nor efficient. According to the World Health Organization, over three billion people worldwide are at these lower rungs, depending on biomass fuels—crop waste, dung, wood, leaves, etc.—and coal to meet their energy needs. A disproportionate number of these individuals reside in Asia and Africa: 95% of the population in Afghanistan uses these fuels, 95% in Chad, 87% in Ghana, 82% in India, 80% in China, and so forth. As incomes rise, we would expect that households would substitute to higher quality fuel choices. However, this process has been quite slow. In fact, the World Bank reports that the use of biomass for all energy sources had remained constant at about 25% since 1975."

Units of Analysis

Domestic energy poverty

Domestic energy poverty refers to a situation where a household does not have access or cannot afford to have the basic energy or energy services to achieve day to day living requirements. These requirements can change from country to country and region to region. The most common needs are lighting, cooking energy, domestic heating or cooling.

Other authors consider different categories of energy needs from "fundamental energy needs" associated to human survival and extremely poor situations. "Basic energy needs" required for attaining basic living standards, which includes all the functions in the previous (cooking, heating and lighting) and, in addition energy to provide basic services linked to health, education and communications. "Energy needs for productive uses" when additionally basic energy needs the user requires energy to make a living; and finally "Energy for recreation", when the user has fulfilled the previous categories and needs energy for enjoyment." Until recently energy poverty definitions took only the minimum energy quantity required into consideration when defining energy poverty, but a different school of thought is that not only energy quantity but the quality and cleanliness of the energy used should be taken into consideration when defining energy poverty.

One such definition reads as:

- "A person is in 'energy poverty' if they do not have access to at least:

- (a) the equivalent of 35 kg LPG for cooking per capita per year from liquid and/or gas fuels or from improved supply of solid fuel sources and improved (efficient and clean) cook stoves

- and

- (b) 120kWh electricity per capita per year for lighting, access to most basic services (drinking water, communication, improved health services, education improved services and others) plus some added value to local production

An 'improved energy source' for cooking is one which requires less than 4 hours person per week per household to collect fuel, meets the recommendations WHO for air quality (maximum concentration of CO of 30 mg/M3 for 24 hours periods and less than 10 mg/ M3 for periods 8 hours of exposure), and the overall conversion efficiency is higher than 25%. "

Challenges to defining and measuring energy poverty

Energy poverty is challenging to define and measure because energy services cannot be measured concretely and there are no universal standards of what are considered basic energy services. Energy services are different ways people use energy like lighting, cooking, space heating, refrigeration, etc.

Composite Indices

Energy Development Index (EDI)

First introduced in 2004 by the International Energy Agency (IEA), the Energy Development Index (EDI) aims to measure a country’s transition to modern fuels. It is calculated as the weighted average of four indicators: “1) Per capita commercial energy consumption as an indicator of the overall economic development of a country; 2) Per capita consumption of electricity in the residential sector as a metric of electricity reliability and customers׳ ability to financially access it; 3) Share of modern fuels in total residential energy sector consumption to indicate access to modern cooking fuels; 4) Share of population with access to electricity.” (The EDI was modeled after the Human Development Index (HDI).) Because the EDI is calculated as the average of indicators which measure the quality and quantity of energy services at a national level, the EDI provides a metric that provides an understanding of the national level of energy development. At the same time, this means that the EDI is not well-equipped to describe energy poverty at a household level.

Multidimensional Energy Poverty Index (MEPI)

Measures whether an individual is energy poor or rich based on how intensely they experience energy deprivation. Energy deprivation is categorized by seven indicators: “access to light, modern cooking fuel, fresh air, refrigeration, recreation, communication, and space cooling.” An individual is considered energy poor if they experience a predetermined number of energy deprivations. The MEPI is calculated by multiplying the ratio of people identified as energy poor to the total sample size and the average intensity of energy deprivation of the energy poor. Some strengths of the MEPI is that it takes into account the number of energy poor along with the intensity of their energy poverty. On the other hand, because it collects data at a household or individual level, it is harder to understand the broader national context.

Energy Poverty Index (EPI)

Developed by Mirza and Szirmai in their 2010 study to measure energy poverty in Pakistan, the Energy Poverty Index (EPI) is calculated by averaging the energy shortfall and energy inconvenience of a household. Energy inconvenience is measured through indicators such as: “Frequency of buying or collecting a source of energy; Distance from household traveled; Means of transport used; Household member’s involvement in energy acquisition; Time spent on energy collection per week; Household health; Children’s involvement in energy collection.” Energy shortfall is measured as the lack of sufficient energy to meet basic household needs. This index weighs more heavily the impact of the usability of energy services rather than its access. Similar to the MEPI, the EPI collects data at a micro-level which lends to greater understanding of energy poverty at the household level.

Intersectional issues

Like other economic justice issues, energy poverty often exacerbates existing vulnerabilities amongst already vulnerable communities.

Gender

In developing countries, women and girls health, educational, and career opportunities are significantly affected by energy because they are usually responsible for providing the primary energy for households. Women and girls spend significant amount of time looking for fuel sources like wood, paraffin, dung, etc. leaving them less time to pursue education, leisure, and their careers. Additionally, using biomass as fuel for heating and cooking disproportionately affects women and children as they are the primary family members responsible for cooking and other domestic activities within the home. Being more vulnerable to indoor air pollution from burning biomass, 85% of the 2 million deaths from indoor air pollution are attributed to women and children. In developed countries, women are more vulnerable to experiencing energy poverty because of their relatively low income compared to the high cost of energy services. For example, women-headed households made up 38% of the 5.6 million French households who were unable to adequately heat their homes. Older women are particularly more vulnerable to experiencing energy poverty because of structural gender inequalities in financial resources and ability to invest in energy saving strategies.

Education

With many dimensions of poverty, education is a very powerful agent for mitigating the effects of energy poverty. Limited electricity access affects students’ quality of education because it can limit the amount of time students can study by not having reliable energy access to study after sunset. Additionally, having consistent access to energy means that girl children, who are usually responsible for collecting fuel for their household, have more time to focus on their studies and attend school.

90 percent of children in sub-Saharan Africa go to primary schools that lack electricity. In Burundi and Guinea only 2% of schools are electrified, while in DR Congo there is only 8% school electrification for a population of 75.5 million (43% of whom are under 14 years). In the DRC alone, by these statistics, there are almost 30 million children attending school without power.

Education is a key component in growing human capital which in turn facilitates economic growth by enabling people to be more productive workers in the economy. As developing nations accumulate more capital, they can invest in building modern energy services while households gain more options to pursue modern energy sources and alleviate energy poverty.

Health

Due to traditional gender roles, women are generally responsible to gathering traditional biomass for energy. Women also spend much time cooking in a kitchen. Spending significant time harvesting energy resources means women have less time to devote to other activities, and the physically straining labor brings chronic fatigue to women. Moreover, women and children, who stick around their mothers to help with domestic chores, respectively, are in danger of long-term exposure to indoor air pollution caused by burning traditional biomass fuels. During combustion, carbon monoxide, particulates, benzene, and the likes threaten their health. As a result, many women and children suffer from acute respiratory infections, lung cancer, asthma, and other diseases. "The health consequences of using biomass in an unsustainable way are staggering. According to the World Health Organization, exposure to indoor air pollution is responsible for the nearly two million excess deaths, primarily women and children, from cancer, respiratory infections and lung diseases and for four percent of the global burden of disease. In relative terms, deaths related to biomass pollution kill more people than malaria (1.2 million) and tuberculosis (1.6 million) each year around the world."

Another connection between energy poverty and health is that households who are energy poor are more likely to use traditional biomass such as wood and cow dung to fulfill their energy needs. However, burning wood and cow dung leads to incomplete combustion and releases black carbon into the atmosphere. Black carbon may be a health hazard.

Development

"Energy provides services to meet many basic human needs, particularly heat, motive power (e.g. water pumps and transport) and light. Business, industry, commerce and public services such as modern healthcare, education and communication are highly dependent on access to energy services. Indeed, there is a direct relationship between the absence of adequate energy services and many poverty indicators such as infant mortality, illiteracy, life expectancy and total fertility rate. Inadequate access to energy also exacerbates rapid urbanization in developing countries, by driving people to seek better living conditions. Increasing energy consumption has long been tied directly to economic growth and improvement in human welfare. However it is unclear whether increasing energy consumption is a necessary precondition for economic growth, or vice versa. Although developed countries are now beginning to decouple their energy consumption from economic growth (through structural changes and increases in energy efficiency), there remains a strong direct relationship between energy consumption and economic development in developing countries."

Climate Change

In 2018, 70% of greenhouse gas emissions were a result of energy production and use. With more countries aiming to transition to modern energy services and provide energy accessibility to more people, there is a risk that greenhouse gas emissions will increase proportionally. Historically, 5% of countries account for 67.74% of total emissions and 50% of the lowest-emitting countries produce only 0.74% of total historic greenhouse gas emissions. Thus, the distribution, production, and consumption of energy services is highly unequal and reflects the greater systemic barriers that prevent people from accessing and using energy services. Additionally, there is a greater emphasis on developing countries to invest in renewable sources of energy rather than following the energy development patterns of developed nations.

Regional Analysis

Energy poverty is a complex issue that is sensitive to the nuances of the culture, time, and space of a region. Thus, the terms “Global North/South” are generalizations and not always sufficient to describe the nuances of energy poverty, although there are broad trends in how energy poverty is experienced and mitigated between the Global North and South.

Global North

Energy poverty is most commonly discussed as “fuel poverty” in the Global North where discourse is focused on households' access to energy sources to heat, cool, and power their homes. Fuel poverty is driven by high energy costs, low household incomes, and inefficient appliances. (a global perspective) Additionally, older people are more vulnerable to experiencing fuel poverty because of their income status and lack of access to energy-saving technologies. According to the European Fuel Poverty and Energy Efficiency (EPEE), approximately 50-125 million people live in fuel poverty. Like energy poverty, fuel poverty is hard to define and measure because of its many nuances. The United Kingdom (UK) and Ireland, are one of the few countries which have defined fuel poverty to be if 10% of a household's income is spent on heating/cooling. Another EPEE project found that 1 in 7 households in Europe were on the margins of fuel poverty by using three indicators of checking for leaky roofs, arrears on utility bills, ability to pay for adequate heating, mold in windows. High energy prices, insufficient insulation in dwellings, and low incomes contribute to increased vulnerability to fuel poverty. Climate change adds more pressure as weather events become more cold and hot, thereby increasing demand for fuel to cool and heat the home. The ability to provide adequate heating during cold weather has implications for people’s health as cold weather can be an antagonistic factor to cardiovascular and respiratory illness.

Global South

Energy poverty in the Global South is largely driven by a lack of access to modern energy sources because of poor energy infrastructure, weak energy service markets, and insufficient household incomes to afford energy services. However, recent research suggests that alleviating energy poverty requires more than building better power grids because there is a complex web of political, economic, and cultural factors that influence a region’s ability to transition to modern energy sources. Energy poverty is strongly linked to many sustainable development goals because greater energy access enables people to exercise more of their capabilities. For example: greater access to clean energy for cooking improves the health of women by reducing the indoor air pollution associated with burning traditional biomasses for cooking; farmers can find better prices for their crops using telecommunication networks; people have more time to pursue leisure and other activities which can increase household income from the time saved from looking for firewood and other traditional biomasses, etc. Because of the impact of energy poverty in sustainable development, energy poverty is largely seen through the lens of another avenue in which to promote sustainable development in regions within the Global South.

Africa

One of Africa’s unique challenges with energy poverty is its rapid urbanization and booming urban centers. Based on urbanization trends in Asia, there has been precedent that urbanization led to broader transitions to modern energy services. However, access to modern energy services in cities is predicated by an increase in income, which is difficult to find in the economies of many African cities. This has led to only 25% of the Africans living in urban centers to have electricity access. Furthermore, as Africa’s population increases access to energy has not increased proportionally. Between 1970-1990, only 50 million people gained access to electricity against a population gain of 150 million. The largest barriers people in urban centers face in accessing energy is the huge cost compared to their relatively low incomes. The urban poor spend 10-30% of their income on energy, whereas the non-poor spend only 5-7% of their income.

Addressing energy poverty

Energy is important for not only economic development but also public health. In developing countries, governments should make efforts on reducing energy poverty that have negative impacts on economic development and public health. The number of people who currently use modern energy should increase as the developing world governments take actions to reduce social costs and to increase social benefits by gradually spreading modern energy to their people in rural areas. However, the developing world governments have been experiencing difficulties in promoting the distributions of modern energy like electricity. In order to build energy infrastructure that generate and deliver electricity to each household, astronomical amount of money are first invested. And lack of high technologies needed for modern energy development have kept the developing countries from accessing modern energy. Such circumstances are huge hurdles; as a result, it is difficult that the developing countries governments participate in effective development of energy without external aids. International cooperation is necessary for framing developing countries' stable future energy infrastructure and institutions. Although their energy situation have not been improved much over the past decades, current international aids are playing an important role in reducing the gap between developing and developed countries associated with the use of modern energy. With the international aids, it will take less time to reduce the gap when comparing to nonexistence of international cooperation.

The World Bank says that financial help should not be general fossil fuel subsidies, but should instead be targeted to those in need.

International efforts

China and India which account for about one third of the global population have booming economies, and other developing nations show similar trends in rapid economic and population growth. As a result of modernization and industrialization, energy demand for modern energy sources also grows. One challenge for developing nations is to support the growing energy needs of their growing populations by expanding their energy infrastructure. Without intentional policy-making and action, more people in developing countries will face extreme difficulties in accessing modern energy services.

International development agencies intervention methods have not been entirely successful. "International cooperation needs to be shaped around a small number of key elements that are all familiar to energy policy, such as institutional support, capacity development, support for national and local energy plans, and strong links to utility/public sector leadership. Africa has all the human and material resources to end poverty but is poor in using those resources for the benefit of its people. This includes national and international institutions as well as the ability to deploy technologies, absorb and disseminate financing, provide transparent regulation, introduce systems of peer review, and share and monitor relevant information and data."

European Union

There is an increasing focus on energy poverty in the European Union, where in 2013 its European Economic and Social Committee formed an official opinion on the matter recommending Europe focus on energy poverty indicators, analysis of energy poverty, considering an energy solidarity fund, analyzing member states' energy policy in economic terms, and a consumer energy information campaign. In 2016, it was reported how several million people in Spain live in conditions of energy poverty. These conditions have led to a few deaths and public anger at the electricity suppliers' artificial and "absurd pricing structure" to increase their profits. In 2017, poor households of Cyprus were found to live in low indoor thermal quality, i.e. their average indoor air temperatures were outside the accepted limits of the comfort zone for the island, and their heating energy consumption was found to be lower than the country's average for the clusters characterized by high and partial deprivation. This is because low income households cannot afford to use the required energy to achieve and maintain the indoor thermal requirements.

Global Environmental Facility

"In 1991, the World Bank Group, international financial institution that provides loans to developing countries for capital programs, established the Global Environmental Facility (GEF) to address global environmental issues in partnership with international institutions, private sector, etc., especially by providing funds to developing countries’ all kinds of projects. The GEF provides grants to developing countries and countries with economies in transition for projects related to biodiversity, climate change, international waters, land degradation, the ozone layer, and persistent organic pollutants. These projects benefit the global environment, linking local, national, and global environmental challenges and promoting sustainable livelihoods. GEF has allocated $10 billion, supplemented by more than $47 billion in cofinancing, for more than 2,800 projects in more than 168 developing countries and countries with economies in transition. Through its Small Grants Programme (SGP), the GEF has also made more than 13,000 small grants directly to civil society and community-based organizations, totalling $634 million. The GEF partnership includes 10 agencies: the UN Development Programme; the UN Environment Programme; the World Bank; the UN Food and Agriculture Organization; the UN Industrial Development Organization; the African Development Bank; the Asian Development Bank; the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development; the Inter-American Development Bank; and the International Fund for Agricultural Development. The Scientific and Technical Advisory Panel provides technical and scientific advice on the GEF's policies and projects."

Climate Investment Funds

"The Climate Investment Funds (CIF) comprises two Trust Funds, each with a specific scope and objective and its own governance structure: the Clean Technology Fund (CTF) and the Strategic Climate Fund (SCF). The CTF promotes investments to initiate a shift towards clean technologies. The CTF seeks to fill a gap in the international architecture for development finance available at more concessional rates than standard terms used by the Multilateral Development Banks (MDBs) and at a scale necessary to help provide incentives to developing countries to integrate nationally appropriate mitigation actions into sustainable development plans and investment decisions. The SCF serves as an overarching fund to support targeted programs with dedicated funding to pilot new approaches with potential for scaled-up, transformational action aimed at a specific climate change challenge or sectoral response. One of SCF target programs is the Program for Scaling-Up Renewable Energy in Low Income Countries (SREP), approved in May 2009, and is aimed at demonstrating the economic, social and environmental viability of low carbon development pathways in the energy sector by creating new economic opportunities and increasing energy access through the use of renewable energy."