Refugee law is the branch of international law which deals with the rights and duties states have vis-a-vis refugees. There are differences of opinion among international law scholars as to the relationship between refugee law and international human rights law or humanitarian law.

The discussion forms part of a larger debate on the fragmentation of international law. While some scholars conceive each branch as a self-contained regime distinct from other branches, others regard the three branches as forming a larger normative system that seeks to protect the rights of all human beings at all time. The proponents of the latter conception view this holistic regime as including norms only applicable to certain situations such as armed conflict and military occupation (IHL) or to certain groups of people including refugees (refugee law), children (the Convention on the Rights of the Child), and prisoners of war (the Geneva Convention (III) relative to the Treatment of Prisoners of War).

Definition of 'refugee'

There is a variety of definitions as to who is regarded as a refugee, usually defined for the purpose of a particular instrument. The variation of definitions regarding refugees has made it difficult to create a concrete and single vision of what constitutes a refugee following the original refugee convention. Article 1 of the 1951 Refugee Convention, as amended by the 1967 Protocol, defines a refugee as:

A person who owing to a well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion, is outside the country of his nationality and is unable or, owing to such fear, is unwilling to avail himself of the protection of that country; or who, not having a nationality and being outside the country of his former habitual residence as a result of such events, is unable or, owing to such fear, is unwilling to return to it.

The 1967 Protocol removed the temporal restrictions that restricted refugee status to those whose circumstances had come about "as a result of events occurring before 1 January 1951," and the geographic restrictions that gave participating states of the Convention the option of interpreting this as "events occurring in Europe" or "events occurring in Europe or elsewhere". However, it also gave those states that had previously ratified the 1951 Convention and chose to use the geographically-restricted definition the option to retain that restriction.

The Organisation of African Unity (OAU) Convention Governing the Specific Aspects of Refugee Problems in Africa adopted a regional treaty based on the Convention, adding to the definition of refugee as:

Any person compelled to leave his/her country owing to external aggression, occupation, foreign domination or events seriously disturbing public order in either part or the whole of his country of origin or nationality.

In 1984, a group of Latin-American governments adopted the Cartagena Declaration on Refugees, which, like the OAU Convention, added more objectivity based on significant consideration to the 1951 Convention. The Cartagena Declaration determine that a refugee includes:

Persons who flee their countries because their lives, safety or freedom have been threatened by generalized violence, foreign aggression, internal conflicts, massive violation of human rights or other circumstances which have seriously disturbed public order.

Difference from 'asylee' and 'displaced person'

Additionally, U.S. Law draws an important distinction between refugees and asylees. A refugee must meet the definition of a refugee, as outlined in the 1951 Convention and be of "special humanitarian concern to the United States." Refugee status can only be obtained from outside the United States. If an individual who meets the definition of a refugee, and is seeking admission in a port of entry is already in the United States, they are eligible to apply for asylum status.

The term displaced person has come to be synonymous with refugees due to a substantial amount of overlap in their legal definitions. However, they are legally distinct, and convey subtle differences. In general, a displaced person refers to "one who has not crossed a national border and thus does not qualify for formal refugee status."

Refugee children

According to the original 1951 Refugee Convention and 1967 Protocol, refugee children were legally indistinguishable from adult refugees. In 1988, the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) Guidelines on Refugee Children were published, specifically designed to address the needs of refugee children, officially granting them internationally recognized human rights.

In 1989, however, the UN signed an additional treaty, the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC), which defined the rights of children and bound its signatories to upholding those rights by international law. Although the CRC was not specific to the rights of refugee minors, it was used as the legal blueprint for handling refugee minor cases, where a minor was defined as any person under the age of 18. In particular, it extends the protection of refugee children by allowing participating nations the capacity to recognize children who do not fall under the strict guidelines of the Convention definition but still should not be sent back to their countries of origin. It also extends the principle of non-refoulement to prohibit the return of a child to their country "where there are grounds for believing that there is a real risk of irreparable harm to the child."

International sources

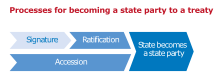

Refugee law encompasses both customary law, peremptory norms, and international legal instruments. The only international instruments directly applying to refugees are the 1951 United Nations Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees and the 1967 Protocol Relating to the Status of Refugees. Both the Convention and the Protocol are open to states, but each may be signed separately. 145 states have ratified the Convention, and 146 have ratified the Protocol. These instruments only apply in the countries that have ratified an instrument, and some countries have ratified these instruments subject to various reservations.

| Year | Law / Treaty / Declaration | Organization / Depositary / Adoptees | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1948 | Universal Declaration of Human Rights | United Nations General Assembly |

|

| 1951 | United Nations Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees | Secretary-General of the United Nations |

|

| 1954 | Treaty on Political Asylum and Refuge | 6 Latin-American countries: Peru, Argentina, Uruguay, Bolivia, Paraguay, and Chile | Signed on 4 August 1939 and entered into force on 29 December 1954. |

| 1966 | Bangkok Principles on Status and Treatment of Refugees | Asian-African Legal Consultative Committee |

|

| 1967 | Protocol Relating to the Status of Refugees | Secretary-General of the United Nations |

|

| 1967 | Declaration on Territorial Asylum | United Nations General Assembly |

|

| 1969 | Convention Governing the Specific Aspects of Refugee Problems in Africa | Organisation of African Unity (OAU) |

|

| 1974 | Declaration on the Protection of Women and Children in Emergency and Armed Conflict | United Nations General Assembly |

|

| 1976 | Recommendation 773 (1976) on the Situation of de facto Refugees | Council of Europe (CoE) |

|

| 1984 | Cartagena Declaration on Refugees

|

10 Latin-American countries: Belize, Colombia, Costa Rica, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Mexico, Nicaragua, Panama, and Venezuela |

|

| 1989 | Convention on the Rights of the Child | Secretary-General of the United Nations |

|

| 1998 | Conclusion on International Protection by the Executive Committee of the High Commissioner's Programme | United Nations Human Rights Council (UNHRC) |

|

| 2001 | Declaration by States Parties to the 1951 Convention and/or its 1967 Protocol Relating to the Status of Refugees |

|

|

| 2003 | Convention Plus | United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) | Refugee resettlement was decided to be of central concern of UNHCR. |

| 2004 | Restriction of Hazardous Substances Directive 2002/95/EC | European Union (EU) | A Council Directive on minimum standards for the qualification and status of third-country nationals and stateless persons as refugees or as persons who otherwise need international protection and content of the protection granted. |

| 2016 | New York Declaration for Refugees and Migrants | United Nations General Assembly |

|

U.S. refugee law

Various regions and countries have different variations of refugee law. They all stem from the 1951 Convention and the 1967 Protocol which relates to refugee status. The United States became a party to this protocol in 1968.

Despite playing an active role in the drafting of the Convention on the Rights of the Child, the United States has yet to ratify the treaty, making it the only nation in the United Nations that is not party to it.

Refugee status first emerged as a legal category in the United States in the 1940s, responding to an influx of Eastern Europeans fleeing Communism. In response to this influx, Congress established refugee migration as "distinct and separate from general immigration admissions" upon the recommendation from the House Committee on Postwar Immigration. The Committee argued that the right to seek asylum be made "an explicit part of United States immigration policy."

Although the aftermath of World War II brought forth a refugee crisis, the large influx and resettlement of Indochinese refugees led to the passage of the Refugee Act of 1980. This law incorporated the International Convention's definitions of a refugee into U.S. law. In doing so, it codified into U.S. law that a refugee was an individual with a "well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership in a particular social group or political opinion." Furthermore, ratifying this Convention meant the elimination of previous "ideological and geographical discriminations" against refugee and asylum seekers. These discriminations were a result of previous U.S. refugee law, which had served mainly as a tool for foreign policy agendas. The law also created the legal basis for the admission of refugees into the U.S. The Refugee Act of 1980 was the first time the United States created an objective decision-making process for asylum and refugee status. This included a joint system between Congress and the Presidency, in which both branches would collaborate to establish annual quotas and determine which national groups would receive prioritized consideration for refugee status. In doing so, the U.S. shifted away from a relatively reactionary system, in which refugee laws were only passed in response to political changes in the international community, primarily the spread of Communism. Instead, under the Refugee Act of 1980, the U.S. established a comprehensive framework for addressing refugee crises preemptively. This framework was built on emerging ideals of "humanitarianism". An important aspect of this law is how an individual goes about applying for status. A person may meet the definition of refugee but may not be granted refugee status. If the individual is inside of the U.S. with a different status or no status, they are granted the status of asylee but not refugee.

In order to be considered a refugee in the United States, an individual must:

- be located outside of the U.S.

- be of specific humanitarian apprehension for the U.S.

- be able to validate previous persecution or feared approaching persecution based on the individual's race, religion, nationality, social class, or political outlook

- not be currently settled in another country

- be admissible to the United States

The first step of being granted this status is to receive a referral to the U.S. Refugee Admissions Program (USRAP). The person is allowed to include their spouse, child, or other family members (only in specific circumstances) when applying for refugee status. After the person is referred, a U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services officer located abroad will conduct an interview to determine refugee resettlement eligibility inside the United States. If the person is approved as a refugee, they will then be provided with many forms of assistance. These include a loan for travel, advice for travel, a medical exam, and a culture orientation. After the refugee is resettled, they are eligible for medical and cash assistance. The Office of Refugee Resettlement (ORR) has a program called the Cash and Medical Assistance Program which completely reimburses the assistance in which states provide refugees. The refugee is eligible for this cash and medical assistance up to eight months after their arrival date.

In the United States, refugees are subject to annual quotas, which are determined by a joint collaboration between the incumbent Presidential administration and Congress. In addition to establishing the annual quota, Congress and the President determine which national groups are of special humanitarian concern to the United States. Since ratifying the 1980 Refugee Act, the United States has admitted over 3.1 million refugees from around the world, many of who were permanently resettled in the United States. Prior to the Trump Administration, the United States was the global leader in admitting refugees and offered refugee status to more individuals than the rest of the world altogether. Under the Trump administration, refugee immigration laws faced many challenges and setbacks, as administration officials sought to rollback immigration laws and decrease the annual number of refugees admitted. Challenges to refugee law included contesting practices of non-refoulement, which has been a long-standing principle of the U.S. immigration system. Attempts to reverse Trump-era policies have been a focus of the subsequent Biden presidential administration. In 2021, it was announced that Biden administration would raise the refugee cap from 15,000 individuals to 62,500 individuals.

Refugee status determination

The burden of refugee status determination (RSD) falls primarily on the state. However, in cases where states are either unwilling or unable, the UNHCR assumes responsibility. In 2013, the UNHCR managed RSD in over 50 countries and worked in parallel with national governments in 20 countries. In the period from 1997 to 2001, the number of RSD applications submitted to the UNHCR nearly doubled.

RSD provides protection for refugees through promoting non-refoulement, resettlement assistance, and direct assistance.

Human rights and refugee law

Human rights are the rights that a person is guaranteed by way of birth. The following are universal human rights that are most relevant to refugees:

- The right to freedom from torture or degrading treatment

- The right to freedom of opinion and expression

- The right to freedom of thought, conscience, and religion

- The right to life, liberty, and security

- Freedom from discrimination

- The right to asylum

Refugee law and international human rights law are closely connected in content but differ in their function. The main difference of their function is the way in which international refugee law considers state sovereignty while international human rights law do not. One of the core principles of international refugee law is the prohibition on refoulement (or the expulsion or return of a refugee), which is the basic idea that a country cannot send back a person to their country of origin if they will face endangerment upon return. In this case, a certain level of sovereignty is taken away from a country. This basic right of non-refoulement conflicts with the basic right of sovereign state to expel any undocumented aliens.