Legal background

Sharia law is the basic Islamic religious law derived from the religious precepts of Islam. The Quran and opinions of Muhammad (i.e., the Hadith and Sunnah) are the primary sources of sharia. For topics and issues not directly addressed in these primary sources, sharia is derived. The derivation differs between the various sects of Islam (Sunni and Shia are the majority), and various jurisprudence schools such as Hanafi, Maliki, Shafi'i, Hanbali and Jafari. The sharia in these schools is derived hierarchically using one or more of the following guidelines: Ijma (usually the consensus of Muhammad's companions), Qiyas (analogy derived from the primary sources), Istihsan (ruling that serves the interest of Islam in the discretion of Islamic jurists) and Urf (customs). Sharia is a significant source of legislation in various Muslim countries. Some apply all or a majority of the sharia, and these include Saudi Arabia, Sudan, Iran, Iraq, Afghanistan, Pakistan, Brunei, United Arab Emirates, Qatar, Yemen and Mauritania, respectively. In these countries, sharia-prescribed punishments, such as beheading, flogging and stoning, continue to be practiced judicially or extrajudicially. The introduction of sharia is a longstanding goal for Islamist movements globally, but attempts to impose sharia have been accompanied by controversy, violence, and even warfare. The differences between sharia and secular law have led to an ongoing controversy as to whether sharia is compatible with secular forms of government, human rights, freedom of thought, and women's rights.

Types of violence

Islam and war

The first military rulings were formulated during the first hundred years after Muhammad established an Islamic state in Medina. These rulings evolved in accordance with the interpretations of the Quran (the Muslim Holy scriptures) and Hadith (the recorded traditions of Muhammad). The key themes in these rulings were the justness of war (see Justice in the Quran), and the injunction to jihad. The rulings do not cover feuds and armed conflicts in general. The millennium of Muslim conquests could be classified as a religious war.

Some have pointed out that the current Western view of the need for a clear separation between Church and State was only first legislated into effect after 18 centuries of Christianity in the Western world. While some majority Muslim governments such as Turkey and many of the majority Muslim former Soviet republics have officially attempted to incorporate this principle of such a separation of powers into their governments, yet, the concept somewhat remains in a state of ongoing evolution and flux within the Muslim world. Islam has never had any officially recognized tradition of pacifism, and throughout its history, warfare has been an integral part of the Islamic theological system.Since the time of Muhammad, Islam has considered warfare to be a legitimate expression of religious faith, and has accepted its use for the defense of Islam. During approximately the first 1,000 years of its existence, the use of warfare by Muslim majority governments often resulted in the de facto propagation of Islam.

The minority Sufi movement within Islam, which includes certain pacifist elements, has often been officially "tolerated" by many Muslim majority governments. Additionally, some notable Muslim clerics, such as Abdul Ghaffar Khan have developed alternative non-violent Muslim theologies. Some hold that the formal juristic definition of war in Islam constitutes an irrevokable and permanent link between the political and religious justifications for war within Islam. The Quranic concept of Jihad includes aspects of both a physical and an internal struggle.

Jihad

Jihad (جهاد) is an Islamic term referring to the religious duty of Muslims to maintain the religion. In Arabic, the word jihād is a noun meaning "to strive, to apply oneself, to struggle, to persevere". A person engaged in jihad is called a mujahid, the plural of which is mujahideen (مجاهدين). The word jihad appears frequently in the Quran, often in the idiomatic expression "striving in the way of God (al-jihad fi sabil Allah)", to refer to the act of striving to serve the purposes of God on this earth. According to the classical Sharia law manual of Shafi'i, Reliance of the Traveller, a Jihad is a war which should be waged against non-Muslims, and the word Jihad is etymologically derived from the word mujahada, a mujahada is a war which should be waged for the purpose of establishing the religion. Jihad is sometimes referred to as the sixth pillar of Islam, though it occupies no such official status. In Twelver Shi'a Islam, however, jihad is one of the ten Practices of the Religion.

Muslims and scholars do not all agree on its definition. Many observers—both Muslim and non-Muslim—as well as the Dictionary of Islam, talk of jihad having two meanings: an inner spiritual struggle (the "greater jihad"), and an outer physical struggle against the enemies of Islam (the "lesser jihad") which may take a violent or non-violent form. Jihad is often translated as "Holy War", although this term is controversial. According to orientalist Bernard Lewis, "the overwhelming majority of classical theologians, jurists", and specialists in the hadith "understood the obligation of jihad in a military sense." Javed Ahmad Ghamidi states that there is consensus among Islamic scholars that the concept of jihad will always include armed struggle against wrongdoers.

According to Jonathan Berkey, jihad in the Quran was maybe originally intended against Muhammad's local enemies, the pagans of Mecca or the Jews of Medina, but the Quranic statements supporting jihad could be redirected once new enemies appeared. The first documentation of the law of Jihad was written by 'Abd al-Rahman al-Awza'i and Muhammad ibn al-Hasan al-Shaybani.

The first forms of military Jihad occurred after the migration (hijra) of Muhammad and his small group of followers to Medina from Mecca and the conversion of several inhabitants of the city to Islam. The first revelation concerning the struggle against the Meccans was surah 22, verses 39–40: The main focus of Muhammad's later years was increasing the number of allies as well as the amount of territory under Muslim control.

According to Richard Edwards and Sherifa Zuhur, offensive jihad was the type of jihad practiced by the early Muslim community, because their weakness meant "no defensive action would have sufficed to protect them against the allied tribal forces determined to exterminate them." Jihad as a collective duty (Fard Kifaya) and offensive jihad are synonymous in classical Islamic law and tradition, which also asserted that offensive jihad could only be declared by the caliph, but an "individually incumbent jihad" (Fard Ayn) required only "awareness of an oppression targeting Islam or Islamic peoples."

Tina Magaard, associate professor at the Aarhus University Department of Business Development and Technology, has analyzed the texts of the 10 largest religions in the world. In an interview, she stated that the basic texts of Islam call for violence and aggression against followers of other faiths to a greater extent than texts of other religions. She has also argued that they contain direct incitements to terrorism.

According to a number of sources, Shia doctrine taught that jihad (or at least full scale jihad) can only be carried out under the leadership of the Imam (who will return from occultation to bring absolute justice to the world). However, "struggles to defend Islam" are permissible before his return.

Caravan raids

Ghazi (غازي) is an Arabic term originally referring to an individual who participates in Ghazw (غزو), meaning military expeditions or raiding; after the emergence of Islam, it took on new connotations of religious warfare. The related word Ghazwa (غزوة) is a singulative form meaning a battle or military expedition, often one led by Muhammad.

The Caravan raids were a series of raids in which Muhammad and his companions participated. The raids were generally offensive and carried out to gather intelligence or seize the trade goods of caravans financed by the Quraysh. The raids were intended to weaken the economy of Mecca by Muhammad. His followers were also impoverished. Muhammad only attacked caravans as a response against Quraysh for confiscating the Muslims' homes and wealth back in Mecca, and driving them into exile.

Quran

Islamic Doctrines and teachings on matters of war and peace have become topics of heated discussion in recent years. Charles Matthews writes that there is a "large debate about what the Quran commands with regard to the 'sword verses' and the 'peace verses'". According to Matthews, "the question of the proper prioritization of these verses, and how they should be understood in relation to one another, has been a central issue for Islamic thinking about war." According to Dipak Gupta, "much of the religious justification of violence against nonbelievers (Dar ul Kufr) by the promoters of jihad is based on the Quranic "sword verses". The Quran contains passages that could be used to glorify or endorse violence.

On the other hand, other scholars argue that such verses of the Qur'an are interpreted out of context, Micheline R. Ishay has argued that "the Quran justifies wars for self-defense to protect Islamic communities against internal or external aggression by non-Islamic populations, and wars waged against those who 'violate their oaths' by breaking a treaty". and British orientalist Gottlieb Wilhelm Leitner stated that jihad, even in self-defence, is "strictly limited".

However, according to Oliver Leaman, a number of Islamic jurists asserted the primacy of the "sword verses" over the conciliatory verses in specific historical circumstances. For example, according to Diane Morgan, Ibn Kathir (1301–1372) asserted that the Sword Verse abrogated all peace treaties that had been promulgated between Muhammad and idolaters.

Prior to the Hijra travel Muhammad non-violently struggled against his oppressors in Mecca. It wasn't until after the exile that the Quranic revelations began to adopt a more defensive perspective. From that point onward, those dubious about the need to go to war were typically portrayed as lazy cowards allowing their love of peace to become a fitna to them.

Hadiths

The context of the Quran is elucidated by Hadith (the teachings, deeds and sayings of Muhammad). Of the 199 references to jihad in perhaps the most standard collection of hadith—Bukhari—all refer to warfare.

Quranism

Quranists reject the hadith and only accept the Quran. The extent to which Quranists reject the authenticity of the Sunnah varies, but the more established groups have thoroughly criticised the authenticity of the hadith and refused it for many reasons, the most prevalent being the Quranist claim that hadith is not mentioned in the Quran as a source of Islamic theology and practice, was not recorded in written form until more than two centuries after the death of Muhammad, and contain perceived internal errors and contradictions.

Ahmadiyya

According to Ahmadi belief, Jihad can be divided into three categories: Jihad al-Akbar (Greater Jihad) is that against the self and refers to striving against one's low desires such as anger, lust and hatred; Jihad al-Kabīr (Great Jihad) refers to the peaceful propagation of Islam, with special emphasis on spreading the true message of Islam by the pen; Jihad al-Asghar (Smaller Jihad) is only for self-defence under situations of extreme religious persecution whilst not being able to follow one's fundamental religious beliefs, and even then only under the direct instruction of the Caliph. Ahmadi Muslims point out that as per Islamic prophecy, Mirza Ghulam Ahmad rendered Jihad in its military form as inapplicable in the present age as Islam, as a religion, is not being attacked militarily but through literature and other media, and therefore the response should be likewise. They believe that the answer of hate should be given by love. Concerning terrorism, the fourth Caliph of the Community writes:

As far as Islam is concerned, it categorically rejects and condemns every form of terrorism. It does not provide any cover or justification for any act of violence, be it committed by an individual, a group or a government.

Various Ahmadis scholars, such as Muhammad Ali, Maulana Sadr-ud-Din and Basharat Ahmad, argue that when the Quran's verses are read in context, it clearly appears that the Quran prohibits initial aggression, and allows fighting only in self-defense.

Ahmadi Muslims believe that no verse of the Quran abrogates or cancels another verse. All Quranic verses have equal validity, in keeping with their emphasis on the "unsurpassable beauty and unquestionable validity of the Qur'ān". The harmonization of apparently incompatible rulings is resolved through their juridical deflation in Ahmadī fiqh, so that a ruling (considered to have applicability only to the specific situation for which it was revealed), is effective not because it was revealed last, but because it is most suited to the situation at hand.

Ahmadis are considered non-Muslims by the mainstream Muslims since they consider Mirza Ghulam Ahmad, founder of Ahmadiyya, as the promised Mahdi and Messiah. In a number of Islamic countries, especially Sunni-dominated nations, Ahmadis have been considered heretics and non-Muslim, and have been subject to various forms of religious persecution, discrimination and systematic oppression since the movement's inception in 1889.

Islam and crime

The Islamic criminal law is criminal law in accordance with Sharia. Strictly speaking, Islamic law does not have a distinct corpus of "criminal law." It divides crimes into three different categories depending on the offense – Hudud (crimes "against God", whose punishment is fixed in the Quran and the Hadiths); Qisas (crimes against an individual or family whose punishment is equal retaliation in the Quran and the Hadiths); and Tazir (crimes whose punishment is not specified in the Quran and the Hadiths, and is left to the discretion of the ruler or Qadi, i.e. judge). Some add the fourth category of Siyasah (crimes against government), while others consider it as part of either Hadd or Tazir crimes.

- Hudud is an Islamic concept: punishments which under Islamic law (Shariah) are mandated and fixed by God. The Shariah divided offenses into those against God and those against man. Crimes against God violated His Hudud, or 'boundaries'. These punishments were specified by the Quran, and in some instances by the Sunnah. They are namely for adultery, fornication, homosexuality, illegal sex by a slave girl, accusing someone of illicit sex but failing to present four male Muslim eyewitnesses, apostasy, consuming intoxicants, outrage (e.g. rebellion against the lawful Caliph, other forms of mischief against the Muslim state, or highway robbery), robbery and theft. The crimes against hudud cannot be pardoned by the victim or by the state, and the punishments must be carried out in public.

These punishments range from public lashing to publicly stoning to death, amputation of hands and crucifixion. However, in most Muslim nations in modern times public stoning and execution are relatively uncommon, although they are found in Muslim nations that follow a strict interpretation of sharia, such as Saudi Arabia and Iran.

- Qisas is an Islamic term meaning "retaliation in kind" or revenge, "eye for an eye", "nemesis" or retributive justice. It is a category of crimes in Islamic jurisprudence, where Sharia allows equal retaliation as the punishment. Qisas principle is available against the accused, to the victim or victim's heirs, when a Muslim is murdered, suffers bodily injury or suffers property damage. In the case of murder, Qisas means the right of a murder victim's nearest relative or Wali (legal guardian) to, if the court approves, take the life of the killer. The Quran mentions the "eye for an eye" concept as being ordained for the Children of Israel in Qur'an, 2:178: "O you who have believed, prescribed for you is legal retribution (Qasas) for those murdered – the free for the free, the slave for the slave, and the female for the female. But whoever overlooks from his brother anything, then there should be a suitable follow-up and payment to him with good conduct. This is an alleviation from your Lord and a mercy. But whoever transgresses after that will have a painful punishment." Shi'ite countries that use Islamic Sharia law, such as Iran, apply the "eye for an eye" rule literally.

In the Torah We prescribed for them a life for a life, an eye for an eye, a nose for a nose, an ear for an ear, a tooth for a tooth, an equal wound for a wound: if anyone forgoes this out of charity, it will serve as atonement for his bad deeds. Those who do not judge according to what God has revealed are doing grave wrong. (Qurʾān, 5:45)

- Tazir refers to punishment, usually corporal, for offenses at the discretion of the judge (Qadi) or ruler of the state.

Capital punishment

Beheading

Beheading was the normal method of capital punishment under classical Islamic law. It was also, together with hanging, one of the ordinary methods of execution in the Ottoman Empire.

Currently, Saudi Arabia is the only country in the world which uses decapitation within its Islamic legal system. The majority of executions carried out by the Wahhabi government of Saudi Arabia are public beheadings, which usually cause mass gatherings but are not allowed to be photographed or filmed.

Beheading is reported to have been carried out by state authorities in Iran as recently as 2001, but as of 2014 is no longer in use. It is also a legal form of execution in Qatar and Yemen, but the punishment has been suspended in those countries.

In recent years, non-state Jihadist organizations such as the Islamic State and Tawhid and Jihad either carry out or have carried out beheadings. Since 2002, they have circulated beheading videos as a form of terror and propaganda. Their actions have been condemned by other militant and terrorist groups, and they have also been condemned by mainstream Islamic scholars and organizations.

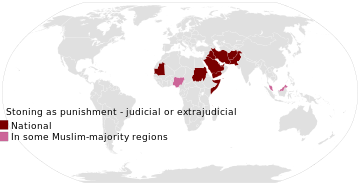

Stoning

Rajm (رجم) is an Arabic word that means "stoning". It is commonly used to refer to the Hudud punishment wherein an organized group throws stones at a convicted individual until that person dies. Under Islamic law, it is the prescribed punishment in cases of adultery committed by a married man or married woman. The conviction requires a confession from either the adulterer/adulteress, or the testimony of four witnesses (as prescribed by the Quran in Surah an-Nur verse 4), or pregnancy outside of marriage.

See below Sexual crimes

Blasphemy

Blasphemy in Islam is impious utterance or action concerning God, Muhammad or anything considered sacred in Islam. The Quran admonishes blasphemy, but does not specify any worldly punishment for it. The hadiths, which are another source of Sharia, suggest various punishments for blasphemy, which may include death. There are a number of surah in Qur'an relating to blasphemy, from which Quranic verses 5:33 and 33:57–61 have been most commonly used in Islamic history to justify and punish blasphemers. Various fiqhs (schools of jurisprudence) of Islam have different punishment for blasphemy, depending on whether blasphemer is Muslim or non-Muslim, man or woman. The punishment can be fines, imprisonment, flogging, amputation, hanging, or beheading.

Muslim clerics may call for the punishment of an alleged blasphemer by issuing a fatwā.[145][146]

According to Islamic sources Nadr ibn al-Harith, who was an Arab Pagan doctor from Taif, used to tell stories of Rustam and Esfandiyār to the Arabs and scoffed Muhammad. After the battle of Badr, al-Harith was captured and, in retaliation, Muhammad ordered his execution in hands of Ali.

Apostasy

Apostasy in Islam is commonly defined as the conscious abandonment of Islam by a Muslim in word or through deed. A majority considers apostasy in Islam to be some form of religious crime, although a minority does not.

The definition of apostasy from Islam and its appropriate punishment(s) are controversial, and they vary among Islamic scholars. Apostasy in Islam may include in its scope not only the renunciation of Islam by a Muslim and the joining of another religion or becoming non-religious, or questioning or denying any "fundamental tenet or creed" of Islam such as the divinity of God, prophethood of Muhammad, or mocking God, or worshipping one or more idols. The apostate (or murtadd مرتد) term has also been used for people of religions that trace their origins to Islam, such as those of the Baháʼí Faith founded in Iran, but who were never actually Muslims themselves. Apostasy in Islam does not include acts against Islam or conversion to another religion that is involuntary, due mental disorders, forced or done as concealment out of fear of persecution or during war (Taqiyya or Kitman).

Historically, the majority of Islamic scholars considered apostasy a hudud crime as well as a sin, an act of treason punishable with the death penalty, and the Islamic law on apostasy and the punishment one of the immutable laws under Islam. The punishment for apostasy includes state enforced annulment of his or her marriage, seizure of the person's children and property with automatic assignment to guardians and heirs, and a death penalty for apostates, typically after a waiting period to allow the apostate time to repent and return to Islam. Female apostates could be either executed, according to Shafi'i, Maliki, and Hanbali schools of Sunni Islamic jurisprudence (fiqh), or imprisoned until she reverts to Islam as advocated by the Sunni Hanafi school and by Shi'a scholars. The kind of apostasy generally deemed to be punishable by the jurists was of the political kind, although there were considerable legal differences of opinion on this matter. There were early Islamic scholars who did not agree with the death penalty and prescribed indefinite imprisonment until repentance. The Hanafi jurist Sarakhsi also called for different punishments between the non-seditious religious apostasy and that of seditious and political nature, or high treason. Some modern scholars also argue that the death penalty is an inappropriate punishment, inconsistent with the Quranic injunctions such as Quran 88:21–22 or "no compulsion in religion"; and/or that it is not a general rule but enacted at a time when the early Muslim community faced enemies who threatened its unity, safety, and security, and needed to prevent and punish the equivalent of desertion or treason, and should be enforced only if apostasy becomes a mechanism of public disobedience and disorder (fitna). According to Khalid Abu El Fadl, moderate Muslims reject such penalty.

To the Ahmadi Muslim sect, there is no punishment for apostasy, neither in the Qur'an nor as taught by the founder of Islam, Muhammad. This position of the Ahmadi sect is not widely accepted in other sects of Islam, and the Ahmadi sect acknowledges that major sects have a different interpretation and definition of apostasy in Islam. Ulama of major sects of Islam consider the Ahmadi Muslim sect as kafirs (infidels) and apostates.

Under current laws in Islamic countries, the actual punishment for the apostate ranges from execution to prison term to no punishment. Islamic nations with sharia courts use civil code to void the Muslim apostate's marriage and deny child custody rights, as well as his or her inheritance rights for apostasy. Twenty-three Muslim-majority countries, as of 2013, additionally covered apostasy in Islam through their criminal laws. Today, apostasy is a crime in 23 out 49 Muslim majority countries. It is subject in some countries, such as Iran and Saudi Arabia, to the death penalty, although executions for apostasy are rare. Apostasy is legal in secular Muslim countries such as Turkey. In numerous Islamic majority countries, many individuals have been arrested and punished for the crime of apostasy without any associated capital crimes. In a 2013 report based on an international survey of religious attitudes, more than 50% of the Muslim population in 6 Islamic countries supported the death penalty for any Muslim who leaves Islam (apostasy). A similar survey of the Muslim population in the United Kingdom, in 2007, found nearly a third of 16 to 24-year-old faithfuls believed that Muslims who convert to another religion should be executed, while less than a fifth of those over 55 believed the same.

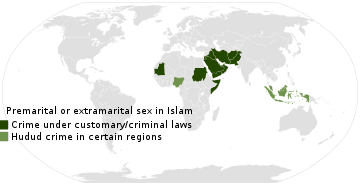

Sexual crimes

Zina is an Islamic law, both in the four schools of Sunni fiqh (Islamic jurisprudence) and the two schools of Shi'a fiqh, concerning unlawful sexual relations between Muslims who are not married to one another through a Nikah. It includes extramarital sex and premarital sex, such as adultery (consensual sexual relations outside marriage), fornication (consensual sexual intercourse between two unmarried persons), illegal sex by a slave girl, and in some interpretations sodomy (anal intercourse between male same-sex partners). Traditionally, a married or unmarried Muslim male could have sex outside marriage with a non-Muslim slave girl, with or without her consent, and such sex was not considered zina.

According to Quran 24:4, the proof that adultery has occurred requires four eyewitnesses to the act, which must have been committed by a man and a woman not validly married to one another, and the act must have been wilfully committed by consenting adults. Proof can also be determined by a confession. But this confession must be voluntary, and based on legal counsel; it must be repeated on four separate occasions, and made by a person who is sane. Otherwise, the accuser is then accorded a sentence for defamation (which means flogging or a prison sentence), and his or her testimony is excluded in all future court cases. There is disagreement between Islamic scholars on whether female eyewitnesses are acceptable witnesses in cases of zina (for other crimes, sharia considers two female witnesses equal the witness of one male).

Zina is a Hudud crime, stated in multiple sahih hadiths to deserve the stoning (Rajm) punishment. In others stoning is prescribed as punishment for illegal sex between man and woman, In some sunnah, the method of stoning, by first digging a pit and partly burying the person's lower half in it, is described. Based on these hadiths, in some Muslim countries, married adulterers are sentenced to death, while consensual sex between unmarried people is sentenced with flogging a 100 times. Adultery can be punished by up to one hundred lashes, though this is not binding in nature and the final decision will always be in the hands of a judge appointed by the state or community. However, no mention of stoning or capital punishment for adultery is found in the Quran and only mentioning lashing as punishment for adultery. Nevertheless, most scholars maintain that there is sufficient evidence from hadiths to derive a ruling.

Sharia law makes a distinction between adultery and rape and applies different rules. In the case of rape, the adult male perpetrator (i.e. rapist) of such an act is to receive the ḥadd zinā, but the non-consenting or invalidly consenting female (i.e. rape victim), proved by four eyewitnesses, is to be regarded as innocent of zinā and relieved of the ḥadd punishment. Confession and four witness-based prosecutions of zina are rare. Most cases of prosecutions are when the woman becomes pregnant, or when she has been raped, seeks justice and the sharia authorities charge her for zina, instead of duly investigating the rapist. Some fiqhs (schools of Islamic jurisprudence) created the principle of shubha (doubt), wherein there would be no zina charges if a Muslim man claims he believed he was having sex with a woman he was married to or with a woman he owned as a slave.

Zina only applies for unlawful sex between free Muslims; the rape of a non-Muslim slave woman is not zina as the act is considered an offense not against the raped slave woman, but against the owner of the slave.

The zina and rape laws of countries under Sharia law are the subjects of a global human rights debate and one of many items of reform and secularization debate with respect to Islam. Contemporary human right activists refer this as a new phase in the politics of gender in Islam, the battle between forces of traditionalism and modernism in the Muslim world, and the use of religious texts of Islam through state laws to sanction and practice gender-based violence.

In contrast to human rights activists, Islamic scholars and Islamist political parties consider 'universal human rights' arguments as imposition of a non-Muslim culture on Muslim people, a disrespect of customary cultural practices and sexual codes that are central to Islam. Zina laws come under hudud—seen as crime against Allah; the Islamists refer to this pressure and proposals to reform zina and other laws as 'contrary to Islam'. Attempts by international human rights to reform religious laws and codes of Islam has become the Islamist rallying platforms during political campaigns.

Violence against LGBT people

The Quran contains seven references to fate of "the people of Lut", and their destruction is explicitly associated with their sexual practices: Given the fact that the Quran is allegedly vague regarding the punishment for homosexual sodomy, Islamic jurists turned to the collections of the hadith and the seerah (accounts of Muhammad's life) to support their argument for Hudud punishment. There were varying opinions on how the death penalty was to be carried out. Abu Bakr apparently recommended toppling a wall on the evil-doer, or else burning alive, while Ali ibn Abi Talib ordered death by stoning for one "luti" and had another thrown head-first from the top of a minaret—according to Ibn Abbas, this last punishment must be followed by stoning. With a few exceptions, all scholars of Sharia or Islamic law interpret homosexual activity as a punishable offence as well as a sin. There is no specific punishment prescribed, however, and this is usually left to the discretion of the local authorities on Islam. There are several methods by which sharia jurists have advocated the punishment of gays or lesbians who are sexually active. One form of execution involves an individual convicted of homosexual acts being stoned to death by a crowd of Muslims. Other Muslim jurists have established an ijma ruling which states that those persons who are committing homosexual acts should be thrown from rooftops or other high places, and this is the perspective of most Salafists.

Today, homosexuality is not socially or legally accepted in most of the Islamic world. In Afghanistan, Brunei, Iran, Mauritania, Nigeria, Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates and Yemen, homosexual acts carries the death penalty. In other Muslim-majority countries, such as Algeria, Gaza Strip, the Maldives, Malaysia, Pakistan, Qatar, Somalia, Sudan, and Syria, it is illegal.

Same-sex sexual intercourse is legal in 20 Muslim-majority nations (Albania, Azerbaijan, Bahrain, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Burkina Faso, Chad, Djibouti, Guinea-Bissau, Lebanon, Iraq, Jordan, Kazakhstan, Kosovo, Kyrgyzstan, Mali, Niger, Tajikistan, Turkey, the West Bank (State of Palestine), and most of Indonesia (except the province of Aceh), as well as Northern Cyprus). In Albania, Lebanon, and Turkey, there have been discussions about legalizing same-sex marriage. Homosexual relations between females are legal in Kuwait, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan, but homosexual acts between males are illegal.

Most Muslim-majority countries and the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation (OIC) have opposed moves to advance LGBT rights at the United Nations, in the General Assembly and/or the UNHRC. In May 2016, a group of 51 Muslim states blocked 11 gay and transgender organizations from attending a high-level meeting on ending AIDS at the United Nations. However, Albania, Guinea-Bissau and Sierra Leone have signed a UN Declaration supporting LGBT rights. Kosovo as well as the (not internationally recognized) Muslim-majority Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus also have anti-discrimination laws in place.

On 12 June 2016, 49 people were killed and 53 other people were injured in a mass shooting at the Pulse gay nightclub in Orlando, Florida, in the second-deadliest mass shooting by an individual and the deadliest incident of violence against LGBT people in U.S. history. The shooter, Omar Mateen, pledged allegiance to the Islamic State. Investigators have classified the act as an Islamic terrorist attack and a hate crime, despite the fact that he was suffering from mental health issues and he acted alone. Upon further review, investigators indicated that Omar Mateen showed few signs of radicalization, suggesting that the shooter's pledge of allegiance to the Islamic State may have been a calculated move which he made in order to garner more news coverage for himself. Afghanistan, Algeria, Azerbaijan, Bahrain, Djibouti, Egypt, Iraq, Iran, Pakistan, Saudi Arabia, Turkey, Turkmenistan and the United Arab Emirates condemned the attack. Many American Muslims, including community leaders, swiftly condemned the attack. Prayer vigils for the victims were held at mosques across the country. The Florida mosque where Mateen sometimes prayed issued a statement in which it condemned the attack and offered its condolences to the victims. The Council on American–Islamic Relations called the attack "monstrous" and offered its condolences to the victims. CAIR Florida urged Muslims to donate blood and contribute funds in support of the victims' families.

Domestic violence

In Islam, while certain interpretations of Surah, An-Nisa, 34 in the Quran find that a husband hitting a wife is allowed., this has also been disputed.

While some authors, such as Phyllis Chesler, argue that Islam is connected to violence against women, especially in the form of honor killings, others, such as Tahira Shahid Khan, a professor specializing in women's issues at the Aga Khan University in Pakistan, argue that it is the domination of men and inferior status of women in society that lead to these acts, not the religion itself. Public (such as through the media) and political discourse debating the relation between Islam, immigration, and violence against women is highly controversial in many Western countries.

Many scholars claim Shari'a law encourages domestic violence against women, when a husband suspects nushuz (disobedience, disloyalty, rebellion, ill conduct) in his wife. Other scholars claim wife beating, for nashizah, is not consistent with modern perspectives of Qur'an. Some conservative translations find that Muslim husbands are permitted to act what is known in Arabic as Idribuhunna with the use of "light force," and sometimes as much as to strike, hit, chastise, or beat. Contemporary Egyptian scholar Abd al-Halim Abu Shaqqa refers to the opinions of jurists Ibn Hajar al-Asqalani, a medieval Shafiite Sunni scholar of Islam who represents the entire realm of Shaykh al Islam, and al-Shawkani, a Yemeni Salafi scholar of Islam, jurist and reformer, who state that hitting should only occur in extraordinary cases. Some Islamic scholars and commentators have emphasized that hitting, even where permitted, is not to be harsh.

Other interpretations of the verse claim it does not support hitting a woman, but separating from her. Variations in interpretation are due to different schools of Islamic jurisprudence, histories and politics of religious institutions, conversions, reforms, and education.

Although Islam permits women to divorce for domestic violence, they are subject to the laws of their nation which might make it quite difficult for a woman to obtain a divorce. In deference to Surah 4:34, many nations with Shari'a law have refused to consider or prosecute cases of domestic abuse.

Terrorism

Pacifism in Islam

Different Muslim movements through history had linked pacifism with Muslim theology. However, warfare has been an integral part of Islamic history both for the defense and the spread of the faith since the time of Muhammad.

Peace is an important aspect of Islam, and Muslims are encouraged, but not required to strive for peace and find peaceful solutions to all problems. However, most Muslims are generally not pacifists, because the teachings in the Qur'an and the Hadith allow Muslims to wage wars if they can be justified. According to James Turner Johnson, there is no normative tradition of pacifism in Islam.

Prior to the Hijra travel, Muhammad waged a non-violent struggle against his opponents in Mecca. It was not until after the exile that the Quranic revelations began to adopt a more violent perspective. Fighting in self-defense is not only legitimate but considered obligatory upon Muslims, according to the Qur'an. The Qur'an, however, says that should the enemy's hostile behavior cease, then the reason for engaging the enemy also lapses.

Statistics

Older statistical academic studies have found evidence that violent crime is less common among Muslim populations than it is among non-Muslim populations. However, those studies insufficiently account for different definitions and report rate of violent crimes in different legal systems (e.g. domestic violence). The average homicide rate in the Muslim world was 2.4 per 100,000, less than a third of non-Muslim countries which had an average homicide rate of 7.5 per 100,000. The average homicide rate among the 19 most populous Muslim countries was 2.1 per 100,000, less than a fifth of the average homicide rate among the 19 most populous Christian countries which was 11.0 per 100,000, including 5.6 per 100,000 in the United States. A negative correlation was found between a country's homicide rate and its percentage of Muslims, in contrast to a positive correlation found between a country's homicide rate and its percentage of Christians. According to Professor Steven Fish: "The percentage of the society that is made up of Muslims is an extraordinarily good predictor of a country’s murder rate. More authoritarianism in Muslim countries does not account for the difference. I have found that controlling for political regime in statistical analysis does not change the findings. More Muslims, less homicide." At the same time, Fish states that: "In a recent book I reported that between 1994 and 2008, the world suffered 204 high-casualty terrorist bombings. Islamists were responsible for 125, or 61 percent of these incidents, which accounted for 70 percent of all deaths." Professor Jerome L. Neapolitan compared low crime rates in Islamic countries to low crime in Japan, comparing the role of Islam to that of Japan's Shinto and Buddhist traditions in fostering cultures emphasizing the importance of community and social obligation, contributing to less criminal behaviour than other nations.

Gallup and Pew polls

Polls have found Muslim-Americans to report less violent views than any other religious group in America. 89% of Muslim-Americans claimed that the killing of civilians is never justified, compared to 71% of Catholics and Protestants, 75% of Jews, and 76% of atheists and non-religious groups. When Gallup asked if it is justifiable for the military to kill civilians, the percentage of people who said it is sometimes justifiable were 21% among Muslims, 58% among Protestants and Catholics, 52% among Jews, and 43% among atheists.

According to 2006 data, Pew Research said that 46% of Nigerian Muslims, 29% of Jordan Muslims, 28% of Egyptian Muslims, 15% of British Muslims, and 8% of American Muslims thought suicide bombings are often or sometimes justified. The figure was unchanged – still 8% – for American Muslims by 2011. Pew in 2009 found that, among Muslims asked if suicide bombings against civilians was justifiable, 43% said it was justifiable in Nigeria, 38% in Lebanon, 15% in Egypt, 13% in Indonesia, 12% in Jordan, 7% among Arab Israelis, 5% in Pakistan, and 4% in Turkey.Pew Research in 2010 found that in Jordan, Lebanon, and Nigeria, roughly 50% of Muslims had favourable views of Hezbollah, and that Hamas also saw similar support.

Counter-terrorism researchers suggests that support for suicide bombings is rooted in opposition to real or perceived foreign military occupation, rather than Islam, according to a Department of Defense-funded study by University of Chicago researcher Robert Pape. The Pew Research Center also found that support for the death penalty as punishment for "people who leave the Muslim religion" was 86% in Jordan, 84% in Egypt, 76% in Pakistan, 51% in Nigeria, 30% in Indonesia, 6% in Lebanon and 5% in Turkey. The different factors at play (e.g. sectarianism, poverty, etc.) and their relative impacts are not clarified.

The Pew Research Center's 2013 poll showed that the majority of 14,244 Muslim, Christian and other respondents in 14 countries with substantial Muslim populations are concerned about Islamic extremism and hold negative views on known terrorist groups.

Gallup poll

Gallup poll collected extensive data in a project called "Who Speaks for Islam?". John Esposito and Dalia Mogahed present data relevant to Islamic views on peace, and more, in their book Who Speaks for Islam? The book reports Gallup poll data from random samples in over 35 countries using Gallup's various research techniques (e.g. pairing male and female interviewers, testing the questions beforehand, communicating with local leaders when approval is necessary, travelling by foot if that is the only way to reach a region, etc.)

There was a great deal of data. It suggests, firstly, that individuals who dislike America and consider the September 11 attacks to be "perfectly justified" form a statistically distinct group, with much more extreme views. The authors call this 7% of Muslims "Politically Radicalized". They chose that title "because of their radical political orientation" and clarify "we are not saying that all in this group commit acts of violence. However, those with extremist views are a potential source for recruitment or support for terrorist groups." The data also indicates that poverty is not simply to blame for the comparatively radical views of this 7% of Muslims, who tend to be better educated than moderates.

The authors say that, contrary to what the media may indicate, most Muslims believe that the September 11 attacks cannot actually be justified at all. The authors called this 55% of Muslims "Moderates". Included in that category were an additional 12% who said the attacks almost cannot be justified at all (thus 67% of Muslims were classified as Moderates). 26% of Muslims were neither moderates nor radicals, leaving the remaining 7% called "Politically Radicalized". Esposito and Mogahed explain that the labels should not be taken as being perfectly definitive. Because there may be individuals who would generally not be considered radical, although they believe the attacks were justified, or vice versa.

Perceptions of Islam

Negative perceptions

Philip W. Sutton and Stephen Vertigans describe Western views on Islam as based on a stereotype of it as an inherently violent religion, characterizing it as a 'religion of the sword'. They characterize the image of Islam in the Western world as a religion which is "dominated by conflict, aggression, 'fundamentalism', and global-scale violent terrorism."

Juan Eduardo Campo writes that, "Europeans (have) viewed Islam in various ways: sometimes as a backward, violent religion; sometimes as an Arabian Nights fantasy; and sometimes as a complex and changing product of history and social life." Robert Gleave writes that, "at the centre of popular conceptions of Islam as a violent religion are the punishments carried out by regimes hoping to bolster both their domestic and international Islamic credentials."

The 9/11 attack on the US has led many non-Muslims to indict Islam as a violent religion. According to Corrigan and Hudson, "some conservative Christian leaders (have) complained that Islam (is) incompatible with what they believed to be a Christian America." Examples of evangelical Christians who have expressed such sentiments include Franklin Graham, an American Christian evangelist and missionary, and Pat Robertson, an American media mogul, an executive chairman, and a former Southern Baptist minister. According to a survey conducted by LifeWay Research, a research group affiliated with the Southern Baptist Convention, said that two out of three Protestant pastors believe that Islam is a "dangerous" religion. Ed Stetzer, President of LifeWay, said "It's important to note our survey asked whether pastors viewed Islam as 'dangerous,' but that does not necessarily mean 'violent." Dr. Johannes J.G. Jansen was an Arabist who wrote an essay titled "Religious Roots of Muslim Violence", in which he discusses all aspects of the issue at length and unequivocally concludes that Muslim violence is mostly based on Islamic religious commands.

Media coverage of terrorist attacks plays a critical role in creating negative perceptions of Islam and Muslims. Powell described how Islam initially appeared in U.S. news cycles because of its relationships to oil, Iraq, Iran, Afghanistan, and terrorism (92). Thus the audience was provided the base to associate Muslims to control of the resource of oil, war, and terrorism. A total of 11 terrorist attacks in the U.S. soil since the 9/11 and their content coverage (in 1,638 news stories) in the national media had been analyzed "through frames composed of labels, common themes, and rhetorical associations" (Powell 94). The key findings are summarized below:

- The media coverage of terrorism in the U.S. feeds a culture of fear of Islam and describes the United States as a good Christian nation (Powell 105).

- A clear pattern of reporting had been detected that differentiates "terrorists who were Muslim with international ties and terrorists who were U.S. citizens with no clear international ties" (Powell 105). This was utilized to frame "war of Islam on the United States".

- "Muslim Americans are no longer ‘'free'’ to practice and to name their religion without fear of prosecution, judgment, or connection to terrorism." (Powell 107)

Islamophobia

Favorable perceptions

In response to these perceptions, Ram Puniyani, a secular activist and writer, says that "Islam does not condone violence but, like other religions, does believe in self-defence".

Mark Juergensmeyer describes the teachings of Islam as ambiguous about violence. He states that, like all religions, Islam occasionally allows for force while stressing that the main spiritual goal is one of nonviolence and peace. Ralph W. Hood, Peter C. Hill and Bernard Spilka write in The Psychology of Religion: An Empirical Approach, "Although it would be a mistake to think that Islam is inherently a violent religion, it would be equally inappropriate to fail to understand the conditions under which believers might feel justified in acting violently against those whom their tradition feels should be opposed."

Similarly, Chandra Muzaffar, a political scientist, Islamic reformist and activist, says, "The Quranic exposition on resisting aggression, oppression and injustice lays down the parameters within which fighting or the use of violence is legitimate. What this means is that one can use the Quran as the criterion for when violence is legitimate and when it is not."