Satellite image, October 2010 | |

| |

| Geography | |

| Location | Northwestern Europe |

| Coordinates | 53°N 8°W |

| Archipelago | British Isles |

| Adjacent to | Atlantic Ocean |

| Area | 84,421 km2 (32,595 sq mi) |

| Area rank | 20th |

| Coastline | 7,527 km (4677.1 mi) |

| Highest elevation | 1,041 m (3415 ft) |

| Highest point | Carrauntoohil |

| Administration | |

| Largest city | Dublin, pop. 1,458,154 Metropolitan Area (2022) |

| Country | Northern Ireland |

| Largest city | Belfast, pop. 671,559 Metropolitan Area (2011) |

| Demographics | |

| Demonym | Irish |

| Population | 7,185,600 (2023 estimate) |

| Population rank | 19th |

| Pop. density | 82.2/km2 (212.9/sq mi) |

| Languages | |

| Ethnic groups | |

| Additional information | |

| Time zone | |

| • Summer (DST) | |

Ireland (/ˈaɪərlənd/ ⓘ, IRE-lənd; Irish: Éire [ˈeːɾʲə] ⓘ; Ulster-Scots: Airlann [ˈɑːrlən]) is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean, in Northwestern Europe. It is separated from Great Britain to its east by the North Channel, the Irish Sea, and St George's Channel. Ireland is the second-largest island of the British Isles, the third-largest in Europe, and the twentieth-largest in the world. Geopolitically, the island is divided between the Republic of Ireland (officially named Ireland), a sovereign state covering five-sixths of the island, and Northern Ireland, which is part of the United Kingdom. As of 2022, the population of the entire island is just over 7 million, with 5.1 million in the Republic of Ireland and 1.9 million in Northern Ireland, ranking it the second-most populous island in Europe after Great Britain.

The geography of Ireland comprises relatively low-lying mountains surrounding a central plain, with several navigable rivers extending inland. Its lush vegetation is a product of its mild but changeable climate which is free of extremes in temperature. Much of Ireland was woodland until the end of the Middle Ages. Today, woodland makes up about 10% of the island, compared with a European average of over 33%, with most of it being non-native conifer plantations. The Irish climate is influenced by the Atlantic Ocean and thus very moderate, and winters are milder than expected for such a northerly area, although summers are cooler than those in continental Europe. Rainfall and cloud cover are abundant.

Gaelic Ireland had emerged by the 1st century AD. The island was Christianised from the 5th century onwards. During this period Ireland was divided into many petty kingships under provincial kingships (Cúige "fifth" of the traditional provinces) vying for dominance and the title of High King of Ireland. In the late 8th to early 11th century AD, Viking raids and settlements took place culminating in the Battle of Clontarf on 23 April 1014 which resulted in the ending of Viking power in Ireland. Following the 12th-century Anglo-Norman invasion, England claimed sovereignty. However, English rule did not extend over the whole island until the 16th–17th century Tudor conquest, which led to colonisation by settlers from Britain. In the 1690s, a system of Protestant English rule was designed to materially disadvantage the Catholic majority and Protestant dissenters, and was extended during the 18th century. With the Acts of Union in 1801, Ireland became a part of the United Kingdom. A war of independence in the early 20th century was followed by the partition of the island, leading to the creation of the Irish Free State, which became increasingly sovereign over the following decades until it declared a republic in 1948 (Republic of Ireland Act, 1948) and Northern Ireland, which remained a part of the United Kingdom. Northern Ireland saw much civil unrest from the late 1960s until the 1990s. This subsided following the Good Friday Agreement in 1998. In 1973, both the Republic of Ireland and the United Kingdom, with Northern Ireland as part of it, joined the European Economic Community. Following a referendum vote in 2016, the United Kingdom, Northern Ireland included, left the European Union (EU) in 2020. Northern Ireland was granted a limited special status and allowed to operate within the EU single market for goods without being in the European Union.

Irish culture has had a significant influence on other cultures, especially in the field of literature. Alongside mainstream Western culture, a strong indigenous culture exists, as expressed through Gaelic games, Irish music, Irish language, and Irish dance. The island's culture shares many features with that of Great Britain, including the English language, and sports such as association football, rugby, horse racing, golf, and boxing.

Name

The names Ireland and Éire derive from Old Irish Ériu, a goddess in Irish mythology first recorded in the ninth century. The etymology of Ériu is disputed but may derive from the Proto-Indo-European root *h2uer, referring to flowing water.

History

Prehistoric Ireland

During the last glacial period, and until about 16,000 BC, much of Ireland was periodically covered in ice. The relative sea level was less than 50m lower resulting in an ice bridge (but not a land bridge) forming between Ireland and Great Britain. By 14,000 BC this ice bridge existed only between Northern Ireland and Scotland and by 12,000 BC Ireland was completely separated from Great Britain. Later, around 6,100 BC, Great Britain became separated from continental Europe. Until recently, the earliest evidence of human activity in Ireland was dated at 12,500 years ago, demonstrated by a butchered bear bone found in a cave in County Clare. Since 2021, the earliest evidence of human activity in Ireland is dated to 33,000 years ago.

By about 8,000 BC, more sustained occupation of the island has been shown, with evidence for Mesolithic communities around the island.

Some time before 4,000 BC, Neolithic settlers introduced cereal cultivars, domesticated animals such as cattle and sheep, built large timber buildings, and stone monuments. The earliest evidence for farming in Ireland or Great Britain is from Ferriter's Cove, County Kerry, where a flint knife, cattle bones and a sheep's tooth were carbon-dated to c. 4,350 BC. Field systems were developed in different parts of Ireland, including at the Céide Fields, that has been preserved beneath a blanket of peat in present-day Tyrawley. An extensive field system, arguably the oldest in the world, consisted of small divisions separated by dry-stone walls. The fields were farmed for several centuries between 3,500 BC and 3,000 BC. Wheat and barley were the principal crops.

The Bronze Age began around 2,500 BC, with technology changing people's everyday lives during this period through innovations such as the wheel, harnessing oxen, weaving textiles, brewing alcohol and metalworking, which produced new weapons and tools, along with fine gold decoration and jewellery, such as brooches and torcs.

Emergence of Celtic Ireland

How and when the island became Celtic has been debated for close to a century, with the migrations of the Celts being one of the more enduring themes of archaeological and linguistic studies. The most recent genetic research strongly associates the spread of Indo-European languages (including Celtic) through Western Europe with a people bringing a composite Beaker culture, with its arrival in Britain and Ireland dated to around the middle of the third millennium BC. According to John T. Koch and others, Ireland in the Late Bronze Age was part of a maritime trading-network culture called the Atlantic Bronze Age that also included Britain, western France and Iberia, and that this is where Celtic languages developed. This contrasts with the traditional view that their origin lies in mainland Europe with the Hallstatt culture.

The long-standing traditional view is that the Celtic language, Ogham script and culture were brought to Ireland by waves of invading or migrating Celts from mainland Europe. This theory draws on the Lebor Gabála Érenn, a medieval Christian pseudo-history of Ireland, along with the presence of Celtic culture, language and artefacts found in Ireland such as Celtic bronze spears, shields, torcs and other finely crafted Celtic associated possessions. The theory holds that there were four separate Celtic invasions of Ireland. The Priteni were said to be the first, followed by the Belgae from northern Gaul and Britain. Later, Laighin tribes from Armorica (present-day Brittany) were said to have invaded Ireland and Britain more or less simultaneously. Lastly, the Milesians (Gaels) were said to have reached Ireland from either northern Iberia or southern Gaul. It was claimed that a second wave named the Euerni, belonging to the Belgae people of northern Gaul, began arriving about the sixth century BC. They were said to have given their name to the island.

The theory was advanced in part because of the lack of archaeological evidence for large-scale Celtic immigration, though it is accepted that such movements are notoriously difficult to identify. Historical linguists are skeptical that this method alone could account for the absorption of Celtic language, with some saying that an assumed processual view of Celtic linguistic formation is 'an especially hazardous exercise'. Genetic lineage investigation into the area of Celtic migration to Ireland has led to findings that showed no significant differences in mitochondrial DNA between Ireland and large areas of continental Europe, in contrast to parts of the Y-chromosome pattern. When taking both into account, a study concluded that modern Celtic speakers in Ireland could be thought of as European "Atlantic Celts" showing a shared ancestry throughout the Atlantic zone from northern Iberia to western Scandinavia rather than substantially central European. In 2012, research showed that the occurrence of genetic markers for the earliest farmers was almost eliminated by Beaker-culture immigrants: they carried what was then a new Y-chromosome R1b marker, believed to have originated in Iberia about 2,500 BC. The prevalence amongst modern Irish men of this mutation is a remarkable 84%, the highest in the world, and closely matched in other populations along the Atlantic fringes down to Spain. A similar genetic replacement happened with lineages in mitochondrial DNA. This conclusion is supported by recent research carried out by the geneticist David Reich, who says: "British and Irish skeletons from the Bronze Age that followed the Beaker period had at most 10 per cent ancestry from the first farmers of these islands, with other 90 per cent from people like those associated with the Bell Beaker culture in the Netherlands." He suggests that it was Beaker users who introduced an Indo-European language, represented here by Celtic (i.e. a new language and culture introduced directly by migration and genetic replacement).

Late antiquity and early medieval times

The earliest written records of Ireland come from classical Greco-Roman geographers. Ptolemy in his Almagest refers to Ireland as Mikra Brettania ("Little Britain"), in contrast to the larger island, which he called Megale Brettania ("Great Britain"). In his map of Ireland in his later work, Geography, Ptolemy refers to Ireland as Iouernia and to Great Britain as Albion. These 'new' names were likely to have been the local names for the islands at the time. The earlier names, in contrast, were likely to have been coined before direct contact with local peoples was made.

The Romans referred to Ireland by this name too in its Latinised form, Hibernia, or Scotia. Ptolemy records 16 nations inhabiting every part of Ireland in 100 AD. The relationship between the Roman Empire and the kingdoms of ancient Ireland is unclear. However, a number of finds of Roman coins have been made, for example at the Iron Age settlement of Freestone Hill near Gowran and Newgrange.

Ireland continued as a patchwork of rival kingdoms; however, beginning in the 7th century, a concept of national kingship gradually became articulated through the concept of a High King of Ireland. Medieval Irish literature portrays an almost unbroken sequence of high kings stretching back thousands of years, but some modern historians believe the scheme was constructed in the 8th century to justify the status of powerful political groupings by projecting the origins of their rule into the remote past.

All of the Irish kingdoms had their own kings but were nominally subject to the high king. The high king was drawn from the ranks of the provincial kings and ruled also the royal kingdom of Meath, with a ceremonial capital at the Hill of Tara. The concept did not become a political reality until the Viking Age and even then was not a consistent one. Ireland did have a culturally unifying rule of law: the early written judicial system, the Brehon Laws, administered by a professional class of jurists known as the brehons.

The Chronicle of Ireland records that in 431, Bishop Palladius arrived in Ireland on a mission from Pope Celestine I to minister to the Irish "already believing in Christ". The same chronicle records that Saint Patrick, Ireland's best known patron saint, arrived the following year. There is continued debate over the missions of Palladius and Patrick, but the consensus is that they both took place and that the older druid tradition collapsed in the face of the new religion. Irish Christian scholars excelled in the study of Latin and Greek learning and Christian theology. In the monastic culture that followed the Christianisation of Ireland, Latin and Greek learning was preserved in Ireland during the Early Middle Ages in contrast to elsewhere in Western Europe, where the Dark Ages followed the Fall of the Western Roman Empire.

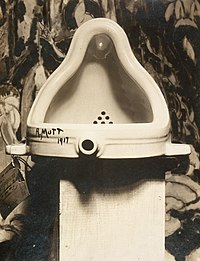

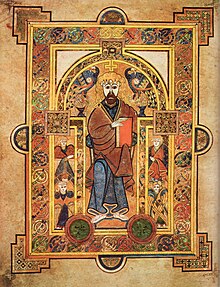

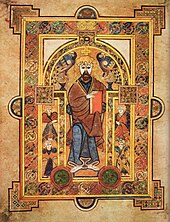

The arts of manuscript illumination, metalworking and sculpture flourished and produced treasures such as the Book of Kells, ornate jewellery and the many carved stone crosses that still dot the island today. A mission founded in 563 on Iona by the Irish monk Saint Columba began a tradition of Irish missionary work that spread Celtic Christianity and learning to Scotland, England and the Frankish Empire on continental Europe after the fall of Rome. These missions continued until the late Middle Ages, establishing monasteries and centres of learning, producing scholars such as Sedulius Scottus and Johannes Eriugena and exerting much influence in Europe.

From the 9th century, waves of Viking raiders plundered Irish monasteries and towns. These raids added to a pattern of raiding and endemic warfare that was already deep-seated in Ireland. The Vikings were involved in establishing most of the major coastal settlements in Ireland: Dublin, Limerick, Cork, Wexford, Waterford, as well as other smaller settlements.

Norman and English invasions

On 1 May 1169, an expedition of Cambro-Norman knights, with an army of about 600 men, landed at Bannow Strand in present-day County Wexford. It was led by Richard de Clare, known as 'Strongbow' owing to his prowess as an archer. The invasion, which coincided with a period of renewed Norman expansion, was at the invitation of Dermot Mac Murrough, King of Leinster.

In 1166, Mac Murrough had fled to Anjou, France, following a war involving Tighearnán Ua Ruairc, of Breifne, and sought the assistance of the Angevin King Henry II, in recapturing his kingdom. In 1171, Henry arrived in Ireland in order to review the general progress of the expedition. He wanted to re-exert royal authority over the invasion which was expanding beyond his control. Henry successfully re-imposed his authority over Strongbow and the Cambro-Norman warlords and persuaded many of the Irish kings to accept him as their overlord, an arrangement confirmed in the 1175 Treaty of Windsor.

The invasion was legitimised by reference to provisions of the alleged Papal Bull Laudabiliter, issued by an Englishman, Adrian IV, in 1155. The document apparently encouraged Henry to take control in Ireland in order to oversee the financial and administrative reorganisation of the Irish Church and its integration into the Roman Church system. Some restructuring had already begun at the ecclesiastical level following the Synod of Kells in 1152. There has been significant controversy regarding the authenticity of Laudabiliter, and there is no general agreement as to whether the bull was genuine or a forgery. Further, it had no standing in the Irish legal system.

In 1172, Pope Alexander III further encouraged Henry to advance the integration of the Irish Church with Rome. Henry was authorised to impose a tithe of one penny per hearth as an annual contribution. This church levy, called Peter's Pence, is extant in Ireland as a voluntary donation. In turn, Henry assumed the title of Lord of Ireland which Henry conferred on his younger son, John Lackland, in 1185. This defined the Anglo-Norman administration in Ireland as the Lordship of Ireland. When Henry's successor died unexpectedly in 1199, John inherited the crown of England and retained the Lordship of Ireland. Over the century that followed, Norman feudal law gradually replaced the Gaelic Brehon Law across large areas, so that by the late 13th century the Norman-Irish had established a feudal system throughout much of Ireland. Norman settlements were characterised by the establishment of baronies, manors, towns and the seeds of the modern county system. A version of Magna Carta (the Great Charter of Ireland), substituting Dublin for London and the Irish Church for, the English church at the time, the Catholic Church, was published in 1216 and the Parliament of Ireland was founded in 1297.

Gaelicisation

From the mid-14th century, after the Black Death, Norman settlements in Ireland went into a period of decline. The Norman rulers and the Gaelic Irish elites intermarried and the areas under Norman rule became Gaelicised. In some parts, a hybrid Hiberno-Norman culture emerged. In response, the Irish parliament passed the Statutes of Kilkenny in 1367. These were a set of laws designed to prevent the assimilation of the Normans into Irish society by requiring English subjects in Ireland to speak English, follow English customs and abide by English law.

By the end of the 15th century, central English authority in Ireland had all but disappeared, and a renewed Irish culture and language, albeit with Norman influences, was again dominant. English Crown control remained relatively unshaken in an amorphous foothold around Dublin known as The Pale, and under the provisions of Poynings' Law of 1494, Irish Parliamentary legislation was subject to the approval of the English Privy Council.

The Kingdom of Ireland

The title of King of Ireland was re-created in 1542 by Henry VIII, the then King of England, of the Tudor dynasty. English rule was reinforced and expanded in Ireland during the latter part of the 16th century, leading to the Tudor conquest of Ireland. A near-complete conquest was achieved by the turn of the 17th century, following the Nine Years' War and the Flight of the Earls.

This control was consolidated during the wars and conflicts of the 17th century, including the English and Scottish colonisation in the Plantations of Ireland, the Wars of the Three Kingdoms and the Williamite War. Irish losses during the Wars of the Three Kingdoms (which, in Ireland, included the Irish Confederacy and the Cromwellian conquest of Ireland) are estimated to include 20,000 battlefield casualties. 200,000 civilians are estimated to have died as a result of a combination of war-related famine, displacement, guerrilla activity and pestilence throughout the war. A further 50,000 were sent into indentured servitude in the West Indies. Physician-general William Petty estimated that 504,000 Catholic Irish and 112,000 Protestant settlers died, and 100,000 people were transported, as a result of the war. If a prewar population of 1.5 million is assumed, this would mean that the population was reduced by almost half.

The religious struggles of the 17th century left a deep sectarian division in Ireland. Religious allegiance now determined the perception in law of loyalty to the Irish King and Parliament. After the passing of the Test Act 1672, and the victory of the forces of the dual monarchy of William and Mary over the Jacobites, Roman Catholics and nonconforming Protestant Dissenters were barred from sitting as members in the Irish Parliament. Under the emerging Penal Laws, Irish Roman Catholics and Dissenters were increasingly deprived of various civil rights, even the ownership of hereditary property. Additional regressive punitive legislation followed in 1703, 1709 and 1728. This completed a comprehensive systemic effort to materially disadvantage Roman Catholics and Protestant Dissenters while enriching a new ruling class of Anglican conformists. The new Anglo-Irish ruling class became known as the Protestant Ascendancy.

The "Great Frost" struck Ireland and the rest of Europe between December 1739 and September 1741, after a decade of relatively mild winters. The winters destroyed stored crops of potatoes and other staples, and the poor summers severely damaged harvests. This resulted in the famine of 1740. An estimated 250,000 people (about one in eight of the population) died from the ensuing pestilence and disease. The Irish government halted export of corn and kept the army in quarters but did little more. Local gentry and charitable organisations provided relief but could do little to prevent the ensuing mortality.

In the aftermath of the famine, an increase in industrial production and a surge in trade brought a succession of construction booms. The population soared in the latter part of this century and the architectural legacy of Georgian Ireland was built. In 1782, Poynings' Law was repealed, giving Ireland legislative independence from Great Britain for the first time since 1495. The British government, however, still retained the right to nominate the government of Ireland without the consent of the Irish parliament.

1798 Rebellion

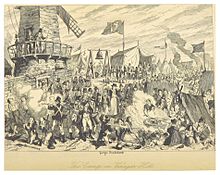

In 1798, members of the Protestant Dissenter tradition (mainly Presbyterian) made common cause with Roman Catholics in a republican rebellion inspired and led by the Society of United Irishmen, with the aim of creating an independent Ireland. Despite assistance from France the rebellion was put down by British and Irish government and yeomanry forces. The rebellion lasted from the 24th of May to the 12th of October that year and saw the establishment of the short lived Irish Republic (1798) in the province of Connacht. It saw numerous battles across the island with an estimated 30,000 people dead.

Union with Great Britain

As a direct result of the 1798 rebellion in its aftermath in 1800, the British and Irish parliaments both passed Acts of Union that, with effect from 1 January 1801, merged the Kingdom of Ireland and the Kingdom of Great Britain to create a United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland.

The passage of the Act in the Irish Parliament was ultimately achieved with substantial majorities, having failed on the first attempt in 1799. According to contemporary documents and historical analysis, this was achieved through a considerable degree of bribery, with funding provided by the British Secret Service Office, and the awarding of peerages, places and honours to secure votes. Thus, the parliament in Ireland was abolished and replaced by a united parliament at Westminster in London, though resistance remained, as evidenced by Robert Emmet's failed Irish Rebellion of 1803.

Aside from the development of the linen industry, Ireland was largely passed over by the Industrial Revolution, partly because it lacked coal and iron resources and partly because of the impact of the sudden union with the structurally superior economy of England, which saw Ireland as a source of agricultural produce and capital.

The Great Famine of 1845–1851 devastated Ireland, as in those years Ireland's population fell by one-third. More than one million people died from starvation and disease, with an additional million people emigrating during the famine, mostly to the United States and Canada. In the century that followed, an economic depression caused by the famine resulted in a further million people emigrating. By the end of the decade, half of all immigration to the United States was from Ireland. The period of civil unrest that followed until the end of the 19th century is referred to as the Land War. Mass emigration became deeply entrenched and the population continued to decline until the mid-20th century. Immediately prior to the famine the population was recorded as 8.2 million by the 1841 census. The population has never returned to this level since. The population continued to fall until 1961; County Leitrim was the final Irish county to record a population increase post-famine, in 2006.

The 19th and early 20th centuries saw the rise of modern Irish nationalism, primarily among the Roman Catholic population. The pre-eminent Irish political figure after the Union was Daniel O'Connell. He was elected as Member of Parliament for Ennis in a surprise result and despite being unable to take his seat as a Roman Catholic. O'Connell spearheaded a vigorous campaign that was taken up by the Prime Minister, the Irish-born soldier and statesman, the Duke of Wellington. Steering the Catholic Relief Bill through Parliament, aided by future prime minister Robert Peel, Wellington prevailed upon a reluctant George IV to sign the Bill and proclaim it into law. George's father had opposed the plan of the earlier Prime Minister, Pitt the Younger, to introduce such a bill following the Union of 1801, fearing Catholic Emancipation to be in conflict with the Act of Settlement 1701.

Daniel O'Connell led a subsequent campaign, for the repeal of the Act of Union, which failed. Later in the century, Charles Stewart Parnell and others campaigned for autonomy within the Union, or "Home Rule". Unionists, especially those located in Ulster, were strongly opposed to Home Rule, which they thought would be dominated by Catholic interests. After several attempts to pass a Home Rule bill through parliament, it looked certain that one would finally pass in 1914. To prevent this from happening, the Ulster Volunteers were formed in 1913 under the leadership of Edward Carson.

Their formation was followed in 1914 by the establishment of the Irish Volunteers, whose aim was to ensure that the Home Rule Bill was passed. The Act was passed but with the "temporary" exclusion of the six counties of Ulster, which later became Northern Ireland. Before it could be implemented, however, the Act was suspended for the duration of the First World War. The Irish Volunteers split into two groups. The majority, approximately 175,000 in number, under John Redmond, took the name National Volunteers and supported Irish involvement in the war. A minority, approximately 13,000, retained the Irish Volunteers' name and opposed Ireland's involvement in the war.

The Easter Rising of 1916 was carried out by the latter group together with a smaller socialist militia, the Irish Citizen Army. The British response, executing 15 leaders of the Rising over a period of ten days and imprisoning or interning more than a thousand people, turned the mood of the country in favour of the rebels. Support for Irish republicanism increased further due to the ongoing war in Europe, as well as the Conscription Crisis of 1918.

The pro-independence republican party, Sinn Féin, received overwhelming endorsement in the general election of 1918, and in 1919 proclaimed an Irish Republic, setting up its own parliament (Dáil Éireann) and government. Simultaneously the Volunteers, which became known as the Irish Republican Army (IRA), launched a three-year guerrilla war, which ended in a truce in July 1921 (although violence continued until June 1922, mostly in Northern Ireland).

Partition

In December 1921, the Anglo-Irish Treaty was concluded between the British government and representatives of the Second Dáil. It gave Ireland complete independence in its home affairs and practical independence for foreign policy, but an opt-out clause allowed Northern Ireland to remain within the United Kingdom, which it immediately exercised. Additionally, Members of the Free State Parliament were required to swear an oath of allegiance to the Constitution of the Irish Free State and make a statement of faithfulness to the king. Disagreements over these provisions led to a split in the nationalist movement and a subsequent Irish Civil War between the new government of the Irish Free State and those opposed to the treaty, led by Éamon de Valera. The civil war officially ended in May 1923 when de Valera issued a cease-fire order.

Independence

During its first decade, the newly formed Irish Free State was governed by the victors of the civil war. When de Valera achieved power, he took advantage of the Statute of Westminster and political circumstances to build upon inroads to greater sovereignty made by the previous government. The oath was abolished and in 1937 a new constitution was adopted. This completed a process of gradual separation from the British Empire that governments had pursued since independence. However, it was not until 1949 that the state was declared, officially, to be the Republic of Ireland.

The state was neutral during World War II, but offered clandestine assistance to the Allies, particularly in the potential defence of Northern Ireland. Despite their country's neutrality, approximately 50,000 volunteers from independent Ireland joined the British forces during the war, four being awarded Victoria Crosses.

The German intelligence was also active in Ireland. Its operations ended in September 1941 when police made arrests based on surveillance carried out on the key diplomatic legations in Dublin. To the authorities, counterintelligence was a fundamental line of defence. With a regular army of only slightly over seven thousand men at the start of the war, and with limited supplies of modern weapons, the state would have had great difficulty in defending itself from invasion from either side in the conflict.

Large-scale emigration marked most of the post-WWII period (particularly during the 1950s and 1980s), but beginning in 1987 the economy improved, and the 1990s saw the beginning of substantial economic growth. This period of growth became known as the Celtic Tiger. The Republic's real GDP grew by an average of 9.6% per annum between 1995 and 1999, in which year the Republic joined the euro. In 2000, it was the sixth-richest country in the world in terms of GDP per capita. Historian R. F. Foster argues the cause was a combination of a new sense of initiative and the entry of American corporations. He concludes the chief factors were low taxation, pro-business regulatory policies, and a young, tech-savvy workforce. For many multinationals, the decision to do business in Ireland was made easier still by generous incentives from the Industrial Development Authority. In addition European Union membership was helpful, giving the country lucrative access to markets that it had previously reached only through the United Kingdom, and pumping huge subsidies and investment capital into the Irish economy.

Modernisation brought secularisation in its wake. The traditionally high levels of religiosity have sharply declined. Foster points to three factors: First, Irish feminism, largely imported from America with liberal stances on contraception, abortion and divorce, undermined the authority of bishops and priests. Second, the mishandling of the paedophile scandals humiliated the Church, whose bishops seemed less concerned with the victims and more concerned with covering up for errant priests. Third, prosperity brought hedonism and materialism that undercut the ideals of saintly poverty.

The financial crisis that began in 2008 dramatically ended this period of boom. GDP fell by 3% in 2008 and by 7.1% in 2009, the worst year since records began (although earnings by foreign-owned businesses continued to grow). The state has since experienced deep recession, with unemployment, which doubled during 2009, remaining above 14% in 2012.

Northern Ireland

Northern Ireland resulted from the division of the United Kingdom by the Government of Ireland Act 1920, and until 1972 was a self-governing jurisdiction within the United Kingdom with its own parliament and prime minister. Northern Ireland, as part of the United Kingdom, was not neutral during the Second World War, and Belfast suffered four bombing raids in 1941. Conscription was not extended to Northern Ireland, and roughly an equal number volunteered from Northern Ireland as volunteered from the Republic of Ireland.

Although Northern Ireland was largely spared the strife of the civil war, in the decades that followed partition there were sporadic episodes of inter-communal violence. Nationalists, mainly Roman Catholic, wanted to unite Ireland as an independent republic, whereas unionists, mainly Protestant, wanted Northern Ireland to remain in the United Kingdom. The Protestant and Catholic communities in Northern Ireland voted largely along sectarian lines, meaning that the government of Northern Ireland (elected by "first-past-the-post" from 1929) was controlled by the Ulster Unionist Party. Over time, the minority Catholic community felt increasingly alienated with further disaffection fuelled by practices such as gerrymandering and discrimination in housing and employment.

In the late 1960s, nationalist grievances were aired publicly in mass civil rights protests, which were often confronted by loyalist counter-protests. The government's reaction to confrontations was seen to be one-sided and heavy-handed in favour of unionists. Law and order broke down as unrest and inter-communal violence increased.[104] The Northern Ireland government requested the British Army to aid the police and protect the Irish Nationalist population. In 1969, the paramilitary Provisional IRA, which favoured the creation of a united Ireland, emerged from a split in the Irish Republican Army and began a campaign against what it called the "British occupation of the six counties".

Other groups, both the unionist and nationalist participated in violence, and a period known as "the Troubles" began. More than 3,600 deaths resulted over the subsequent three decades of conflict. Owing to the civil unrest during the Troubles, the British government suspended home rule in 1972 and imposed direct rule. There were several unsuccessful attempts to end the Troubles politically, such as the Sunningdale Agreement of 1973. In 1998, following a ceasefire by the Provisional IRA and multi-party talks, the Good Friday Agreement was concluded as a treaty between the British and Irish governments, annexing the text agreed in the multi-party talks.

The substance of the Agreement (formally referred to as the Belfast Agreement) was later endorsed by referendums in both parts of Ireland. The Agreement restored self-government to Northern Ireland on the basis of power-sharing in a regional Executive drawn from the major parties in a new Northern Ireland Assembly, with entrenched protections for the two main communities. The Executive is jointly headed by a First Minister and deputy First Minister drawn from the unionist and nationalist parties. Violence had decreased greatly after the Provisional IRA and loyalist ceasefires in 1994, and in 2005, the Provisional IRA announced the end of its armed campaign and an independent commission supervised its disarmament and that of other nationalist and unionist paramilitary organisations.

The Assembly and power-sharing Executive were suspended several times but were restored again in 2007. In that year the British government officially ended its military support of the police in Northern Ireland (Operation Banner) and began withdrawing troops. On 27 June 2012, Northern Ireland's deputy first minister and former IRA commander, Martin McGuinness, shook hands with Queen Elizabeth II in Belfast, symbolising reconciliation between the two sides.

Politics

The island is divided between the Republic of Ireland, an independent state, and Northern Ireland, a constituent country of the United Kingdom. They share an open border and both are part of the Common Travel Area and as a consequence, there is free movement of people, goods, services and capital across the border.

The Republic of Ireland is a member state of the European Union while the United Kingdom is a former member state, having both acceded to its precursor entity, the European Economic Community (EEC), in 1973 but the UK left the European Union in 2020 after a referendum on EU membership was held in 2016 which resulted in 51.9% of UK voters choosing to leave the bloc.

Republic of Ireland

The Republic of Ireland is a parliamentary democracy based on the Westminster system, with a written constitution and a popularly elected president whose role is mostly ceremonial. The Oireachtas is a bicameral parliament, composed of Dáil Éireann (the Dáil), a house of representatives, and Seanad Éireann (the Seanad), an upper house. The government is headed by a prime minister, the Taoiseach, who is appointed by the president on the nomination of the Dáil. Its capital is Dublin.

The Republic of Ireland today ranks among the wealthiest countries in the world in terms of GDP per capita and in 2015 was ranked the sixth most developed nation in the world by the United Nations' Human Development Index. A period of rapid economic expansion from 1995 onwards became known as the Celtic Tiger period, was brought to an end in 2008 with an unprecedented financial crisis and an economic depression in 2009. According to the 2024 Global Peace Index, Ireland is the second most peaceful country in the world.

Northern Ireland

Northern Ireland is a part of the United Kingdom with a local executive and assembly which exercise devolved powers. The executive is jointly headed by the first and deputy first minister, with the ministries being allocated in proportion to each party's representation in the assembly. Its capital is Belfast.

Ultimately political power is held by the UK government, from which Northern Ireland has gone through intermittent periods of direct rule during which devolved powers have been suspended. Northern Ireland elects 18 of the UK House of Commons' 650 MPs. The Northern Ireland Secretary is a cabinet-level post in the British government.

Along with England and Wales and with Scotland, Northern Ireland forms one of the three separate legal jurisdictions of the UK, all of which share the Supreme Court of the United Kingdom as their court of final appeal.

All-island institutions

As part of the Good Friday Agreement, the British and Irish governments agreed on the creation of all-island institutions and areas of cooperation. The North/South Ministerial Council is an institution through which ministers from the Government of Ireland and the Northern Ireland Executive agree all-island policies. At least six of these policy areas must have an associated all-island "implementation body", and at least six others must be implemented separately in each jurisdiction. The implementation bodies are: Waterways Ireland, the Food Safety Promotion Board, InterTradeIreland, the Special European Union Programmes Body, the North/South Language Body and the Foyle, Carlingford and Irish Lights Commission.

The British–Irish Intergovernmental Conference provides for co-operation between the Government of Ireland and the Government of the United Kingdom on all matters of mutual interest, especially Northern Ireland. In light of the Republic's particular interest in the governance of Northern Ireland, "regular and frequent" meetings co-chaired by the Irish Minister for Foreign Affairs and the British Secretary of State for Northern Ireland, dealing with non-devolved matters to do with Northern Ireland and non-devolved all-Ireland issues, are required to take place under the establishing treaty.

The North/South Inter-Parliamentary Association is a joint parliamentary forum for the island of Ireland. It has no formal powers but operates as a forum for discussing matters of common concern between the respective legislatures.

Geography

Ireland is located in the north-west of Europe, between latitudes 51° and 56° N, and longitudes 11° and 5° W. It is separated from Great Britain by the Irish Sea and the North Channel, which has a width of 23 kilometres (14 mi) at its narrowest point. To the west is the northern Atlantic Ocean and to the south is the Celtic Sea, which lies between Ireland and Brittany, in France. Ireland has a total area of 84,421 km2 (32,595 sq mi), of which the Republic of Ireland occupies 83 percent. Ireland and Great Britain, together with many nearby smaller islands, are known collectively as the British Isles. As the term British Isles can be controversial in relation to Ireland, the alternate term Britain and Ireland is sometimes used as a neutral term for the islands.

A ring of coastal mountains surrounds low plains at the centre of the island. The highest of these is Carrauntoohil (Irish: Corrán Tuathail) in County Kerry, which rises to 1,039 m (3,409 ft) above sea level. The most arable land lies in the province of Leinster. Western areas are mainly mountainous and rocky with green panoramic vistas. River Shannon, the island's longest river at 360.5 km (224 mi) long, rises in County Cavan in the north-west and flows through Limerick in the midwest.

Geology

The island consists of varied geological provinces. In the west, around County Galway and County Donegal, is a medium- to high-grade metamorphic and igneous complex of Caledonide affinity, similar to the Scottish Highlands. Across southeast Ulster and extending southwest to Longford and south to Navan is a province of Ordovician and Silurian rocks, with similarities to the Southern Uplands province of Scotland. Further south, along the County Wexford coastline, is an area of granite intrusives into more Ordovician and Silurian rocks, like that found in Wales.

In the southwest, around Bantry Bay and the mountains of MacGillycuddy's Reeks, is an area of substantially deformed, lightly metamorphosed Devonian-aged rocks. This partial ring of "hard rock" geology is covered by a blanket of Carboniferous limestone over the centre of the country, giving rise to a comparatively fertile and lush landscape. The west-coast district of the Burren around Lisdoonvarna has well-developed karst features. Significant stratiform lead-zinc mineralisation is found in the limestones around Silvermines and Tynagh.

Hydrocarbon exploration is ongoing following the first major find at the Kinsale Head gas field off Cork in the mid-1970s. In 1999, economically significant finds of natural gas were made in the Corrib Gas Field off the County Mayo coast. This has increased activity off the west coast in parallel with the "West of Shetland" step-out development from the North Sea hydrocarbon province. In 2000, the Helvick oil field was discovered, which was estimated to contain over 28 million barrels (4,500,000 m3) of oil.

Climate

The island's lush vegetation, a product of its mild climate and frequent rainfall, earns it the sobriquet the Emerald Isle. Overall, Ireland has a mild but changeable oceanic climate with few extremes. The climate is typically insular and temperate, avoiding the extremes in temperature of many other areas in the world at similar latitudes. This is a result of the moist winds which ordinarily prevail from the southwestern Atlantic.

Precipitation falls throughout the year but is light overall, particularly in the east. The west tends to be wetter on average and prone to Atlantic storms, especially in the late autumn and winter months. These occasionally bring destructive winds and higher total rainfall to these areas, as well as sometimes snow and hail. The regions of north County Galway and east County Mayo have the highest incidents of recorded lightning annually for the island, with lightning occurring approximately five to ten days per year in these areas. Munster, in the south, records the least snow whereas Ulster, in the north, records the most.

Inland areas are warmer in summer and colder in winter. Usually around 40 days of the year are below freezing 0 °C (32 °F) at inland weather stations, compared to 10 days at coastal stations. Ireland is sometimes affected by heat waves, most recently in 1995, 2003, 2006, 2013 and 2018. In common with the rest of Europe, Ireland experienced unusually cold weather during the winter of 2010–11. Temperatures fell as low as −17.2 °C (1 °F) in County Mayo on 20 December and up to a metre (3 ft) of snow fell in mountainous areas.

| Climate data for Ireland | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 18.5 (65.3) |

18.1 (64.6) |

23.6 (74.5) |

25.8 (78.4) |

28.4 (83.1) |

33.3 (91.9) |

33.0 (91.4) |

32.1 (89.8) |

29.1 (84.4) |

25.2 (77.4) |

20.1 (68.2) |

18.1 (64.6) |

33.3 (91.9) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −19.1 (−2.4) |

−17.8 (0.0) |

−17.2 (1.0) |

−7.7 (18.1) |

−5.6 (21.9) |

−3.3 (26.1) |

−0.3 (31.5) |

−2.7 (27.1) |

−3 (27) |

−8.3 (17.1) |

−11.5 (11.3) |

−17.5 (0.5) |

−19.1 (−2.4) |

| Source 1: Met Éireann | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: The Irish Times (November record high) | |||||||||||||

Flora and fauna

Unlike Great Britain which had a land bridge with mainland Europe, Ireland only had an ice bridge ending around 14,000 years ago at the end of the last ice age and as a result, it has fewer land animal and plant species than Great Britain or mainland Europe. There are 55 mammal species in Ireland, and of them, only 26 land mammal species are considered native to Ireland. Some species, such as, the red fox, hedgehog and badger, are very common, whereas others, like the Irish hare, red deer and pine marten are less so. Aquatic wildlife, such as species of sea turtle, shark, seal, whale, and dolphin, are common off the coast. About 400 species of birds have been recorded in Ireland. Many of these are migratory, including the barn swallow.

Several different habitat types are found in Ireland, including farmland, open woodland, temperate broadleaf and mixed forests, conifer plantations, peat bogs and a variety of coastal habitats. However, agriculture drives current land use patterns in Ireland, limiting natural habitat preserves, particularly for larger wild mammals with greater territorial needs. With no large apex predators in Ireland other than humans and dogs, such populations of animals as semi-wild deer that cannot be controlled by smaller predators, such as the fox, are controlled by annual culling.

There are no snakes in Ireland, and only one species of reptile (the common lizard) is native to the island. Extinct species include the Irish elk, the great auk, brown bear and the wolf. Some previously extinct birds, such as the golden eagle, have been reintroduced after decades of extirpation.

Ireland is now one of the least forested countries in Europe. Until the end of the Middle Ages, Ireland was heavily forested. Native species include deciduous trees such as oak, ash, hazel, birch, alder, willow, aspen, rowan and hawthorn, as well as evergreen trees such Scots pine, yew, holly and strawberry trees. Only about 10% of Ireland today is woodland; most of this is non-native conifer plantations, and only 2% is native woodland. The average woodland cover of European countries is over 33%. In the Republic, about 389,356 hectares (3,893.56 km2) is owned by the state, mainly by the forestry service Coillte. Remnants of native forest can be found scattered around the island, in particular in the Killarney National Park.

Much of the land is now covered with pasture and there are many species of wild-flower. Gorse (Ulex europaeus), a wild furze, is commonly found growing in the uplands and ferns are plentiful in the more moist regions, especially in the western parts. It is home to hundreds of plant species, some of them unique to the island, and has been "invaded" by some grasses, such as Spartina anglica.

The algal and seaweed flora is that of the cold-temperate variety. The total number of species is 574 The island has been invaded by some algae, some of which are now well established.

Because of its mild climate, many species, including sub-tropical species such as palm trees, are grown in Ireland. Phytogeographically, Ireland belongs to the Atlantic European province of the Circumboreal Region within the Boreal Kingdom. The island can be subdivided into two ecoregions: the Celtic broadleaf forests and North Atlantic moist mixed forests.

Impact of agriculture

The long history of agricultural production, coupled with modern intensive agricultural methods such as pesticide and fertiliser use and runoff from contaminants into streams, rivers and lakes, has placed pressure on biodiversity in Ireland. A land of green fields for crop cultivation and cattle rearing limits the space available for the establishment of native wild species. Hedgerows, however, traditionally used for maintaining and demarcating land boundaries, act as a refuge for native wild flora. This ecosystem stretches across the countryside and acts as a network of connections to preserve remnants of the ecosystem that once covered the island. Subsidies under the Common Agricultural Policy, which supported agricultural practices that preserved hedgerow environments, are undergoing reforms. The Common Agricultural Policy had in the past subsidised potentially destructive agricultural practices, for example by emphasising production without placing limits on indiscriminate use of fertilisers and pesticides; but reforms have gradually decoupled subsidies from production levels and introduced environmental and other requirements. 32% of Ireland's greenhouse gas emissions are correlated to agriculture. Forested areas typically consist of monoculture plantations of non-native species, which may result in habitats that are not suitable for supporting native species of invertebrates. Natural areas require fencing to prevent over-grazing by deer and sheep that roam over uncultivated areas. Grazing in this manner is one of the main factors preventing the natural regeneration of forests across many regions of the country.

Demographics

The population of Ireland is just over 7 million, of which approximately 5.1 million reside in the Republic of Ireland and 1.9 million reside in Northern Ireland.

People have lived in Ireland for over 9,000 years. Early historical and genealogical records note the existence of major groups such as the Cruthin, Corcu Loígde, Dál Riata, Dáirine, Deirgtine, Delbhna, Érainn, Laigin, Ulaid. Later major groups included the Connachta, Ciannachta, Eóganachta. Smaller groups included the aithechthúatha (see Attacotti), Cálraighe, Cíarraige, Conmaicne, Dartraighe, Déisi, Éile, Fir Bolg, Fortuatha, Gailenga, Gamanraige, Mairtine, Múscraige, Partraige, Soghain, Uaithni, Uí Maine, Uí Liatháin. Many survived into late medieval times, others vanished as they became politically unimportant. Over the past 1,200 years, Vikings, Normans, Welsh, Flemings, Scots, English, Africans and Eastern Europeans have all added to the population and have had significant influences on Irish culture.

The population of Ireland rose rapidly from the 16th century until the mid-19th century, interrupted briefly by the Famine of 1740–41, which killed roughly two-fifths of the island's population. The population rebounded and multiplied over the next century, but the Great Famine of the 1840s caused one million deaths and forced over one million more to emigrate in its immediate wake. Over the following century, the population was reduced by over half, at a time when the general trend in European countries was for populations to rise by an average of three-fold.

Ireland's largest religious group is Christianity. The largest denomination is Roman Catholicism, representing over 73% of the island (and about 87% of the Republic of Ireland). Most of the rest of the population adhere to one of the various Protestant denominations (about 48% of Northern Ireland). The largest is the Anglican Church of Ireland. The Muslim community is growing in Ireland, mostly through increased immigration, with a 50% increase in the republic between the 2006 and 2011 census. The island has a small Jewish community. About 4% of the Republic's population and about 14% of the Northern Ireland population describe themselves as of no religion. In a 2010 survey conducted on behalf of the Irish Times, 32% of respondents said they went to a religious service more than once per week.

Divisions and settlements

Traditionally, Ireland is subdivided into four provinces: Connacht (west), Leinster (east), Munster (south), and Ulster (north). In a system that developed between the 13th and 17th centuries, Ireland has 32 traditional counties. Twenty-six of these counties are in the Republic of Ireland, and six are in Northern Ireland. The six counties that constitute Northern Ireland are all in the province of Ulster (which has nine counties in total). As such, Ulster is often used as a synonym for Northern Ireland, although the two are not coterminous. In the Republic of Ireland, counties form the basis of the system of local government. Counties Dublin, Cork, Limerick, Galway, Waterford and Tipperary have been broken up into smaller administrative areas. However, they are still treated as counties for cultural and some official purposes, for example, postal addresses and by the Ordnance Survey Ireland. Counties in Northern Ireland are no longer used for local governmental purposes, but, as in the Republic, their traditional boundaries are still used for informal purposes such as sports leagues and in cultural or tourism contexts.

City status in Ireland is decided by legislative or royal charter. Dublin, with over one million residents in the Greater Dublin Area, is the largest city on the island. Belfast, with 579,726 residents, is the largest city in Northern Ireland. City status does not directly equate with population size. For example, Armagh, with 14,590 is the seat of the Church of Ireland and the Roman Catholic Primate of All Ireland and was re-granted city status by Queen Elizabeth II in 1994 (having lost that status in local government reforms of 1840). In the Republic of Ireland, Kilkenny, the seat of the Butler dynasty, while no longer a city for administrative purposes (since the 2001 Local Government Act), is entitled by law to continue to use the description.

| Cities and towns by population | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Dublin  Belfast |

# | Settlement | City Population |

Urban population |

Metro population |

Cork  Limerick |

| 1 | Dublin | 592,713 | 1,263,219 | 1,458,154 | ||

| 2 | Belfast | 293,298 | 639,000 | |||

| 3 | Cork | 222,333 | 305,222 | |||

| 4 | Limerick | 102,287 |

| |||

| 5 | Galway | 85,910 |

| |||

| 6 | Derry | 85,279 |

| |||

| 7 | Greater Craigavon | 72,301 |

| |||

| 8 | Newtownabbey | 67,599 |

| |||

| 9 | Bangor | 64,596 |

| |||

| 10 | Waterford | 60,079 |

| |||

Migration

The population of Ireland collapsed dramatically during the second half of the 19th century. A population of over eight million in 1841 was reduced to slightly over four million by 1921. In part, the fall in population was caused by death from the Great Famine of 1845 to 1852, which took roughly one million lives. The remaining decline of around three million was due to the entrenched culture of emigration caused by the dire economic state of the country, lasting until the late 20th century.

Emigration from Ireland in the 19th century contributed to the populations of England, the United States, Canada and Australia, in all of which a large Irish diaspora lives. As of 2006, 4.3 million Canadians, or 14% of the population, were of Irish descent, while around one-third of the Australian population had an element of Irish descent. As of 2013, there were 40 million Irish-Americans and 33 million Americans who claimed Irish ancestry.

With growing prosperity since the last decade of the 20th century, Ireland became a destination for immigrants. Since the European Union expanded to include Poland in 2004, Polish people have comprised the largest number of immigrants (over 150,000) from Central Europe. There has also been significant immigration from Lithuania, Czech Republic and Latvia.

The Republic of Ireland in particular has seen large-scale immigration, with 420,000 foreign nationals as of 2006, about 10% of the population. Nearly a quarter of births (24 percent) in 2009 were to mothers born outside of Ireland. Up to 50,000 eastern and central European migrant workers left Ireland in response to the Irish financial crisis.

Languages

The two official languages of the Republic of Ireland are Irish and English. Each language has produced noteworthy literature. Irish, though now only the language of a minority, was the vernacular of the Irish people for thousands of years and was possibly introduced during the Iron Age. It began to be written down after Christianisation in the 5th century and spread to Scotland and the Isle of Man, where it evolved into the Scottish Gaelic and Manx languages, respectively.

The Irish language has a vast treasury of written texts from many centuries and is divided by linguists into Old Irish from the 6th to 10th century, Middle Irish from the 10th to 13th century, Early Modern Irish until the 17th century, and the Modern Irish spoken today. It remained the dominant language of Ireland for most of those periods, having influences from Latin, Old Norse, French and English. It declined under British rule but remained the majority tongue until the early 19th century, and since then has been a minority language.

The Gaelic Revival of the late 19th and early 20th centuries had a long-term influence. Irish is taught in mainstream Irish schools as a compulsory subject, but teaching methods have been criticised for their ineffectiveness, with most students showing little evidence of fluency even after 14 years of instruction.

There is now a growing population of urban Irish speakers in both the Republic and Northern Ireland, especially in Dublin and Belfast, with the children of such Irish speakers sometimes attending Irish-medium schools (Gaelscoil or Gaelscoileanna). It has been argued that they tend to be more highly educated than monolingual English speakers. Recent research suggests that urban Irish is developing in a direction of its own, both in pronunciation and grammar.

Traditional rural Irish-speaking areas, known collectively as the Gaeltacht, are in linguistic decline. The main Gaeltacht areas are in the west, south-west and north-west, in Galway, Mayo, Donegal, western Cork and Kerry with smaller Gaeltacht areas near Dungarvan in Waterford and in Meath.

English in Ireland was first introduced during the Norman invasion. It was spoken by a few peasants and merchants brought over from England and was largely replaced by Irish before the Tudor conquest of Ireland. It was introduced as the official language during the Tudor and Cromwellian conquests. The Ulster plantations gave it a permanent foothold in Ulster, and it remained the official and upper-class language elsewhere, the Irish-speaking chieftains and nobility having been deposed. Language shift during the 19th century replaced Irish with English as the first language for a vast majority of the population.

Fewer than 2% of the population of the Republic of Ireland today speak Irish on a daily basis, and under 10% regularly, outside of the education system and 38% of those over 15 years are classified as "Irish speakers". In Northern Ireland, English is the de facto official language, but official recognition is afforded to Irish, including specific protective measures under Part III of the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages. A lesser status (including recognition under Part II of the Charter) is given to Ulster Scots dialects, which are spoken by roughly 2% of Northern Ireland residents, and also spoken by some in the Republic of Ireland. Since the 1960s with the increase in immigration, many more languages have been introduced, particularly deriving from Asia and Eastern Europe.

Also native to Ireland are Shelta, the language of the nomadic Irish Travellers, Irish Sign Language, and Northern Ireland Sign Language.

Culture

Ireland's culture comprises elements of the culture of ancient peoples, later immigrant and broadcast cultural influences (chiefly Gaelic culture, Anglicisation, Americanisation and aspects of broader European culture). In broad terms, Ireland is regarded as one of the Celtic nations of Europe, alongside Scotland, Wales, Cornwall, Isle of Man and Brittany. This combination of cultural influences is visible in the intricate designs termed Irish interlace or Celtic knotwork. These can be seen in the ornamentation of medieval religious and secular works. The style is still popular today in jewellery and graphic art, as is the distinctive style of traditional Irish music and dance, and has become indicative of modern "Celtic" culture in general.

Religion has played a significant role in the cultural life of the island since ancient times (and since the 17th century plantations, has been the focus of political identity and divisions on the island). Ireland's pre-Christian heritage fused with the Celtic Church following the missions of Saint Patrick in the fifth century. The Hiberno-Scottish missions, begun by the Irish monk Saint Columba, spread the Irish vision of Christianity to pagan England and the Frankish Empire. These missions brought written language to an illiterate population of Europe during the Dark Ages that followed the fall of Rome, earning Ireland the sobriquet, "the island of saints and scholars".

Since the 20th century Irish pubs worldwide have become outposts of Irish culture, especially those with a full range of cultural and gastronomic offerings.

Arts

Literature

Ireland has made a substantial contribution to world literature in all its branches, both in Irish and English. Poetry in Irish is among the oldest vernacular poetry in Europe, with the earliest examples dating from the 6th century. Irish remained the dominant literary language down to the 19th century, despite the spread of English from the 17th century on. Prominent names from the medieval period and later include Gofraidh Fionn Ó Dálaigh (14th century), Dáibhí Ó Bruadair (17th century) and Aogán Ó Rathaille (18th century). Eibhlín Dubh Ní Chonaill (c. 1743 – c. 1800) was an outstanding poet in the oral tradition. The latter part of the 19th century saw a rapid replacement of Irish by English. By 1900, however, cultural nationalists had begun the Gaelic revival, which saw the beginnings of modern literature in Irish. This was to produce a number of notable writers, including Máirtín Ó Cadhain, Máire Mhac an tSaoi and others. Irish-language publishers such as Coiscéim and Cló Iar-Chonnacht continue to produce scores of titles every year.

In English, Jonathan Swift, often called the foremost satirist in the English language, gained fame for works such as Gulliver's Travels and A Modest Proposal. Other notable 18th-century writers of Irish origin included Oliver Goldsmith and Richard Brinsley Sheridan, though they spent most of their lives in England. The Anglo-Irish novel came to the fore in the 19th century, featuring such writers as Charles Kickham, William Carleton, and (in collaboration) Edith Somerville and Violet Florence Martin. The playwright and poet Oscar Wilde, noted for his epigrams, was born in Ireland.

In the 20th century, Ireland produced four winners of the Nobel Prize for Literature: George Bernard Shaw, William Butler Yeats, Samuel Beckett and Seamus Heaney. Although not a Nobel Prize winner, James Joyce is widely considered to be one of the most significant writers of the 20th century. Joyce's 1922 novel Ulysses is considered one of the most important works of Modernist literature and his life is celebrated annually on 16 June in Dublin as "Bloomsday". A comparable writer in Irish is Máirtín Ó Cadhain, whose 1949 novel Cré na Cille is regarded as a modernist masterpiece and has been translated into several languages.

Modern Irish literature is often connected with its rural heritage through English-language writers such as John McGahern and Seamus Heaney and Irish-language writers such as Máirtín Ó Direáin and others from the Gaeltacht.

Music and dance

Music has been in evidence in Ireland since prehistoric times. Although in the early Middle Ages the church was "quite unlike its counterpart in continental Europe", there was a considerable interchange between monastic settlements in Ireland and the rest of Europe that contributed to what is known as Gregorian chant. Outside religious establishments, musical genres in early Gaelic Ireland are referred to as a triad of weeping music (goltraige), laughing music (geantraige) and sleeping music (suantraige). Vocal and instrumental music (e.g. for the harp, pipes, and various string instruments) was transmitted orally, but the Irish harp, in particular, was of such significance that it became Ireland's national symbol. Classical music following European models first developed in urban areas, in establishments of Anglo-Irish rule such as Dublin Castle, St Patrick's Cathedral and Christ Church as well as the country houses of the Anglo-Irish ascendancy, with the first performance of Handel's Messiah (1742) being among the highlights of the baroque era. In the 19th century, public concerts provided access to classical music to all classes of society. Yet, for political and financial reasons Ireland has been too small to provide a living to many musicians, so the names of the better-known Irish composers of this time belong to emigrants.

Irish traditional music and dance have seen a surge in popularity and global coverage since the 1960s. In the middle years of the 20th century, as Irish society was modernising, traditional music had fallen out of favour, especially in urban areas. However during the 1960s, there was a revival of interest in Irish traditional music led by groups such as the Dubliners, the Chieftains, the Wolfe Tones, the Clancy Brothers, Sweeney's Men and individuals like Seán Ó Riada and Christy Moore. Groups and musicians including Horslips, Van Morrison and Thin Lizzy incorporated elements of Irish traditional music into contemporary rock music and, during the 1970s and 1980s, the distinction between traditional and rock musicians became blurred, with many individuals regularly crossing over between these styles of playing. This trend can be seen more recently in the work of artists like Enya, the Saw Doctors, the Corrs, Sinéad O'Connor, Clannad, the Cranberries and the Pogues among others.

Art

The earliest known Irish graphic art and sculpture are Neolithic carvings found at sites such as Newgrange and is traced through Bronze Age artefacts and the religious carvings and illuminated manuscripts of the medieval period. During the course of the 19th and 20th centuries, a strong tradition of painting emerged, including such figures as John Butler Yeats, William Orpen, Jack Yeats and Louis le Brocquy. Contemporary Irish visual artists of note include Sean Scully, Kevin Abosch, and Alice Maher.

Drama and theatre

The Republic of Ireland's national theatre is the Abbey Theatre, which was founded in 1904, and the national Irish-language theatre is An Taibhdhearc, which was established in 1928 in Galway. Playwrights such as Seán O'Casey, Brian Friel, Sebastian Barry, Conor McPherson and Billy Roche are internationally renowned.

Science

The Irish philosopher and theologian Johannes Scotus Eriugena was considered one of the leading intellectuals of the early Middle Ages. Sir Ernest Henry Shackleton, an Irish explorer, was one of the principal figures of Antarctic exploration. He, along with his expedition, made the first ascent of Mount Erebus and the discovery of the approximate location of the South Magnetic Pole. Robert Boyle was a 17th-century natural philosopher, chemist, physicist, inventor and early gentleman scientist. He is largely regarded as one of the founders of modern chemistry and is best known for the formulation of Boyle's law.

19th-century physicist, John Tyndall, discovered the Tyndall effect. Father Nicholas Joseph Callan, professor of natural philosophy in Maynooth College, is best known for his invention of the induction coil, transformer and he discovered an early method of galvanisation in the 19th century.

Other notable Irish physicists include Ernest Walton, winner of the 1951 Nobel Prize in Physics. With Sir John Douglas Cockcroft, he was the first to split the nucleus of the atom by artificial means and made contributions to the development of a new theory of wave equation. William Thomson, or Lord Kelvin, is the person whom the absolute temperature unit, the kelvin, is named after. Sir Joseph Larmor, a physicist and mathematician, made innovations in the understanding of electricity, dynamics, thermodynamics and the electron theory of matter. His most influential work was Aether and Matter, a book on theoretical physics published in 1900.

George Johnstone Stoney introduced the term electron in 1891. John Stewart Bell was the originator of Bell's Theorem and a paper concerning the discovery of the Bell-Jackiw-Adler anomaly and was nominated for a Nobel prize. The astronomer Jocelyn Bell Burnell, from Lurgan, County Armagh, discovered pulsars in 1967. Notable mathematicians include Sir William Rowan Hamilton, famous for work in classical mechanics and the invention of quaternions. Francis Ysidro Edgeworth's contribution, the Edgeworth Box. remains influential in neo-classical microeconomic theory to this day; while Richard Cantillon inspired Adam Smith, among others. John B. Cosgrave was a specialist in number theory and discovered a 2000-digit prime number in 1999 and a record composite Fermat number in 2003. John Lighton Synge made progress in different fields of science, including mechanics and geometrical methods in general relativity. He had mathematician John Nash as one of his students. Kathleen Lonsdale, born in Ireland and most known for her work with crystallography, became the first female president of the British Association for the Advancement of Science.

Ireland has nine universities, seven in the Republic of Ireland and two in Northern Ireland, including Trinity College Dublin and the University College Dublin, as well as numerous third-level colleges and institutes and a branch of the Open University, the Open University in Ireland. Ireland was ranked 19th in the Global Innovation Index in 2024.

Sports

Gaelic football is the most popular sport in Ireland in terms of match attendance and community involvement, with about 2,600 clubs on the island. In 2003 it represented 34% of total sports attendances at events in Ireland and abroad, followed by hurling at 23%, soccer at 16% and rugby at 8%. The All-Ireland Football Final is the most watched event in the sporting calendar. Soccer is the most widely played team game on the island and the most popular in Northern Ireland.

Other sporting activities with the highest levels of playing participation include swimming, golf, aerobics, cycling, and billiards/snooker. Many other sports are also played and followed, including boxing, cricket, fishing, greyhound racing, handball, hockey, horse racing, motor sport, show jumping and tennis.

The island fields a single international team in most sports. One notable exception to this is association football, although both associations continued to field international teams under the name "Ireland" until the 1950s. The sport is also the most notable exception where the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland field separate international teams. Northern Ireland has produced two World Snooker Champions.

Field sports

Gaelic football, hurling and Gaelic handball are the best-known Irish traditional sports, collectively known as Gaelic games. Gaelic games are governed by the Gaelic Athletic Association (GAA), with the exception of women's Gaelic football and camogie (women's variant of hurling), which are governed by separate organisations. The headquarters of the GAA (and the main stadium) is located at Croke Park in north Dublin and has a capacity of 82,500. Many major GAA games are played there, including the semi-finals and finals of the All-Ireland Senior Football Championship and All-Ireland Senior Hurling Championship. During the redevelopment of the Lansdowne Road stadium in 2007–2010, international rugby and soccer were played there. All GAA players, even at the highest level, are amateurs, receiving no wages, although they are permitted to receive a limited amount of sport-related income from commercial sponsorship.

The Irish Football Association (IFA) was originally the governing body for soccer across the island. The game has been played in an organised fashion in Ireland since the 1870s, with Cliftonville F.C. in Belfast being Ireland's oldest club. It was most popular, especially in its first decades, around Belfast and in Ulster. However, some clubs based outside Belfast thought that the IFA largely favoured Ulster-based clubs in such matters as selection for the national team. In 1921, following an incident in which, despite an earlier promise, the IFA moved an Irish Cup semi-final replay from Dublin to Belfast, Dublin-based clubs broke away to form the Football Association of the Irish Free State. Today the southern association is known as the Football Association of Ireland (FAI). Despite being initially blacklisted by the Home Nations' associations, the FAI was recognised by FIFA in 1923 and organised its first international fixture in 1926 (against Italy). However, both the IFA and FAI continued to select their teams from the whole of Ireland, with some players earning international caps for matches with both teams. Both also referred to their respective teams as Ireland.

In 1950, FIFA directed the associations only to select players from within their respective territories and, in 1953, directed that the FAI's team be known only as "Republic of Ireland" and that the IFA's team be known as "Northern Ireland" (with certain exceptions). Northern Ireland qualified for the World Cup finals in 1958 (reaching the quarter-finals), 1982 and 1986 and the European Championship in 2016. The Republic qualified for the World Cup finals in 1990 (reaching the quarter-finals), 1994, 2002 and the European Championship in 1988, 2012 and 2016. Across Ireland, there is significant interest in the English and, to a lesser extent, Scottish soccer leagues.

Ireland fields a single national rugby team and a single association, the Irish Rugby Football Union, governs the sport across the island. The Irish rugby team have played in every Rugby World Cup, making the quarter-finals in eight of them. Ireland also hosted games during the 1991 and the 1999 Rugby World Cups (including a quarter-final). There are four professional Irish teams; all four play in the Pro14 and at least three compete for the Heineken Cup. Irish rugby has become increasingly competitive at both the international and provincial levels since the sport went professional in 1994. During that time, Ulster (1999), Munster (2006 and 2008) and Leinster (2009, 2011 and 2012) have won the Heineken Cup. In addition to this, the Irish International side has had increased success in the Six Nations Championship against the other European elite sides. This success, including Triple Crowns in 2004, 2006 and 2007, culminated with a clean sweep of victories, known as a Grand Slam, in 2009 and 2018.

Boxing

Amateur boxing on the island of Ireland is governed by the Irish Athletic Boxing Association. Ireland has won more medals in boxing than in any other Olympic sport. Michael Carruth won a gold medal and Wayne McCullough won a silver medal in the Barcelona Olympic Games. In 2008 Kenneth Egan won a silver medal in the Beijing Games. Paddy Barnes secured bronze in those games and gold in the 2010 European Amateur Boxing Championships (where Ireland came 2nd in the overall medal table) and 2010 Commonwealth Games. Katie Taylor has won gold in every European and World championship since 2005. In August 2012 at the Olympic Games in London, Taylor created history by becoming the first Irish woman to win a gold medal in boxing in the 60 kg lightweight. More recently, Kellie Harrington won a gold medal at the 2020 Tokyo Olympics.

Other sports

Horse racing and greyhound racing are both popular in Ireland. There are frequent horse race meetings and greyhound stadiums are well-attended. The island is noted for the breeding and training of race horses and is also a large exporter of racing dogs. The horse racing sector is largely concentrated in the County Kildare.

Irish athletics is an all-Ireland sport governed by Athletics Ireland. Sonia O'Sullivan won two medals at 5,000 metres on the track; gold at the 1995 World Championships and silver at the 2000 Sydney Olympics. Gillian O'Sullivan won silver in the 20k walk at the 2003 World Championships, while sprint hurdler Derval O'Rourke won gold at the 2006 World Indoor Championship in Moscow. Olive Loughnane won a silver medal in the 20k walk at the World Athletics Championships in Berlin in 2009.