From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Differences in national income equality around the world as measured by the national

Gini coefficient as of 2018.

The Gini coefficient is a number between 0 and 100, where 0 corresponds

with perfect equality (where everyone has the same income) and 100

corresponds with absolute inequality (where one person has all the

income, and everyone else has zero income).

There are wide varieties of economic inequality, most notably measured using the distribution of income (the amount of money people are paid) and the distribution of wealth

(the amount of wealth people own). Besides economic inequality between

countries or states, there are important types of economic inequality

between different groups of people.

Important types of economic measurements focus on wealth, income, and consumption. There are many methods for measuring economic inequality, with the Gini coefficient being a widely used one. Another type of measure is the Inequality-adjusted Human Development Index, which is a statistic composite index that takes inequality into account. Important concepts of equality include equity, equality of outcome, and equality of opportunity.

Research suggests that greater inequality hinders economic growth, with land and human capital inequality reducing growth more than inequality of income. Whereas globalization has reduced global inequality (between nations), it has increased inequality within nations. Research has generally linked economic inequality to political instability, including democratic breakdown and civil conflict.

Measurements

Share of income of the top 1% for selected developed countries, 1975 to 2015

In 1820, the ratio between the income of the top and bottom 20

percent of the world's population was three to one. By 1991, it was

eighty-six to one. A 2011 study titled "Divided we Stand: Why Inequality Keeps Rising" by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development

(OECD) sought to explain the causes for this rising inequality by

investigating economic inequality in OECD countries; it concluded that

the following factors played a role:

- Changes in the structure of households can play an important

role. Single-headed households in OECD countries have risen from an

average of 15% in the late 1980s to 20% in the mid-2000s, resulting in

higher inequality.

- Assortative mating

refers to the phenomenon of people marrying people with similar

background, for example doctors marrying other doctors rather than

nurses. OECD found out that 40% of couples where both partners work

belonged to the same or neighbouring earnings deciles compared with 33%

some 20 years before.

- In the bottom percentiles, number of hours worked has decreased.

- The main reason for increasing inequality seems to be the difference between the demand for and supply of skills.

The study made the following conclusions about the level of economic inequality:

- Income inequality in OECD countries is at its highest level for

the past half century. The ratio between the bottom 10% and the top 10%

has increased from 1:7 to 1:9 in 25 years.

- There are tentative signs of a possible convergence of inequality

levels towards a common and higher average level across OECD countries.

- With very few exceptions (France, Japan, and Spain), the wages of the 10% best-paid workers have risen relative to those of the 10% lowest paid.

A 2011 OECD study investigated economic inequality in Argentina, Brazil, China, India, Indonesia, Russia and South Africa. It concluded that key sources of inequality in these countries include "a large, persistent informal sector,

widespread regional divides (e.g. urban-rural), gaps in access to

education, and barriers to employment and career progression for women."

Countries by total wealth (trillions USD), Credit Suisse

A study by the World Institute for Development Economics Research at United Nations University reports that the richest 1% of adults alone owned 40% of global assets in the year 2000. The three richest people in the world possess more financial assets than the lowest 48 nations combined. The combined wealth of the "10 million dollar millionaires" grew to nearly $41 trillion in 2008. Oxfam's 2021 report on global inequality said that the COVID-19 pandemic

has increased economic inequality substantially; the wealthiest people

across the globe were impacted the least by the pandemic and their

fortunes recovered quickest, with billionaires seeing their wealth

increase by $3.9 trillion, while at the same time those living on less

than $5.50 a day likely increased by 500 million. The report also

emphasized that the wealthiest 1% are by far the biggest polluters and

main drivers of climate change, and said that government policy should focus on fighting both inequality and climate change simultaneously.

According to PolitiFact, the top 400 richest Americans "have more wealth than half of all Americans combined." According to The New York Times on July 22, 2014, the "richest 1 percent in the United States now own more wealth than the bottom 90 percent". Inherited wealth may help explain why many Americans who have become rich may have had a "substantial head start". In September 2012, according to the Institute for Policy Studies (IPS), "over 60 percent" of the Forbes richest 400 Americans "grew up in substantial privilege". A 2017 report by the IPS said that three individuals, Jeff Bezos, Bill Gates and Warren Buffett,

own as much wealth as the bottom half of the population, or 160 million

people, and that the growing disparity between the wealthy and the poor

has created a "moral crisis", noting that "we have not witnessed such

extreme levels of concentrated wealth and power since the first gilded age a century ago." In 2016, the world's billionaires increased their combined global wealth to a record $6 trillion. In 2017, they increased their collective wealth to 8.9 trillion. In 2018, U.S. income inequality reached the highest level ever recorded by the Census Bureau.

The existing data and estimates suggest a large increase in

international (and more generally inter-macroregional) components

between 1820 and 1960. It might have slightly decreased since that time

at the expense of increasing inequality within countries. The United Nations Development Programme

in 2014 asserted that greater investments in social security, jobs and

laws that protect vulnerable populations are necessary to prevent

widening income inequality.

There is a significant difference in the measured wealth

distribution and the public's understanding of wealth distribution.

Michael Norton of the Harvard Business School and Dan Ariely of the Department of Psychology at Duke University

found this to be true in their research conducted in 2011. The actual

wealth going to the top quintile in 2011 was around 84%, whereas the

average amount of wealth that the general public estimated to go to the

top quintile was around 58%.

According to a 2020 study, global earnings inequality has

decreased substantially since 1970. During the 2000s and 2010s, the

share of earnings by the world's poorest half doubled. Two researchers claim that global income inequality is decreasing due to strong economic growth in developing countries. According to a January 2020 report by the United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, economic inequality between states had declined, but intra-state inequality has increased for 70% of the world population over the period 1990–2015.

In 2015, the OECD reported in 2015 that income inequality is higher

than it has ever been within OECD member nations and is at increased

levels in many emerging economies. According to a June 2015 report by the International Monetary Fund:

Widening income inequality is the defining challenge of

our time. In advanced economies, the gap between the rich and poor is at

its highest level in decades. Inequality trends have been more mixed in

emerging markets and developing countries (EMDCs), with some countries

experiencing declining inequality, but pervasive inequities in access to

education, health care, and finance remain.

In October 2017, the IMF warned that inequality within nations, in

spite of global inequality falling in recent decades, has risen so

sharply that it threatens economic growth and could result in further political polarization.

The Fund's Fiscal Monitor report said that "progressive taxation and

transfers are key components of efficient fiscal redistribution."

In October 2018 Oxfam published a Reducing Inequality Index

which measured social spending, tax and workers' rights to show which

countries were best at closing the gap between the rich and the poor.

Income distribution within individual countries

Countries' income inequality according to their most recent reported

Gini index values as of 2018.

A Gini index

value above 50 is considered high; countries including Brazil,

Colombia, South Africa, Botswana, and Honduras can be found in this

category. A Gini index value of 30 or above is considered medium;

countries including Vietnam, Mexico, Poland, the United States,

Argentina, Russia and Uruguay can be found in this category. A Gini

index value lower than 30 is considered low; countries including

Austria, Germany, Denmark, Norway, Slovenia, Sweden, and Ukraine can be

found in this category.

Various proposed causes of economic inequality

There

are various reasons for economic inequality within societies, including

both global market functions (such as trade, development, and

regulation) as well as social factors (including gender, race, and

education).

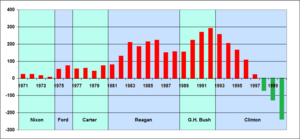

Recent growth in overall income inequality, at least within the OECD

countries, has been driven mostly by increasing inequality in wages and

salaries.

Economist Thomas Piketty argues that widening economic disparity is an inevitable phenomenon of free market capitalism when the rate of return of capital (r) is greater than the rate of growth of the economy (g).

Labour market

A major cause of economic inequality within modern market economies is the determination of wages by the market. Where competition is imperfect; information unevenly distributed; opportunities to acquire education and skills unequal; market failure

results. Since many such imperfect conditions exist in virtually every

market, there is in fact little presumption that markets are in general

efficient. This means that there is an enormous potential role for

government to correct such market failures.

Taxes

Another cause is the rate at which income is taxed coupled with the progressivity of the tax system. A progressive tax is a tax by which the tax rate increases as the taxable base amount increases.

In a progressive tax system, the level of the top tax rate will often

have a direct impact on the level of inequality within a society, either

increasing it or decreasing it, provided that income does not change as

a result of the change in tax regime. Additionally, steeper tax

progressivity applied to social spending can result in a more equal distribution of income across the board. Tax credits such as the Earned Income Tax Credit in the US can also decrease income inequality. The difference between the Gini index for an income distribution before taxation and the Gini index after taxation is an indicator for the effects of such taxation.

Education

Illustration

from a 1916 advertisement for a vocational school in the back of a US

magazine. Education has been seen as a key to higher income, and this

advertisement appealed to Americans' belief in the possibility of

self-betterment, as well as threatening the consequences of downward

mobility in the great

income inequality existing during the

Industrial Revolution.

An important factor in the creation of inequality is variation in individuals' access to education. Education, especially in an area where there is a high demand for workers, creates high wages for those with this education.

However, increases in education first increase and then decrease growth

as well as income inequality. As a result, those who are unable to

afford an education, or choose not to pursue optional education,

generally receive much lower wages. The justification for this is that a

lack of education leads directly to lower incomes, and thus lower

aggregate saving and investment. Conversely, quality education raises incomes and promotes growth because it helps to unleash the productive potential of the poor.

Economic liberalism, deregulation and decline of unions

John Schmitt and Ben Zipperer (2006) of the CEPR point to economic liberalism and the reduction of business regulation along with the decline of union membership as one of the causes of economic inequality. In an analysis of the effects of intensive Anglo-American liberal

policies in comparison to continental European liberalism, where unions

have remained strong, they concluded "The U.S. economic and social

model is associated with substantial levels of social exclusion,

including high levels of income inequality, high relative and absolute

poverty rates, poor and unequal educational outcomes, poor health

outcomes, and high rates of crime and incarceration. At the same time,

the available evidence provides little support for the view that

U.S.-style labor market flexibility

dramatically improves labor-market outcomes. Despite popular prejudices

to the contrary, the U.S. economy consistently affords a lower level of

economic mobility than all the continental European countries for which

data is available."

More recently, the International Monetary Fund has published studies which found that the decline of unionization in many advanced economies and the establishment of neoliberal economics have fueled rising income inequality.

Information technology

The growth in importance of information technology has been credited with increasing income inequality. Technology has been called "the main driver of the recent increases in inequality" by Erik Brynjolfsson, of MIT.

In arguing against this explanation, Jonathan Rothwell notes that if

technological advancement is measured by high rates of invention, there

is a negative correlation between it and inequality. Countries with high

invention rates — "as measured by patent applications filed under the

Patent Cooperation Treaty" — exhibit lower inequality than those with

less. In one country, the United States, "salaries of engineers and

software developers rarely reach" above $390,000/year (the lower limit

for the top 1% earners).

Globalization

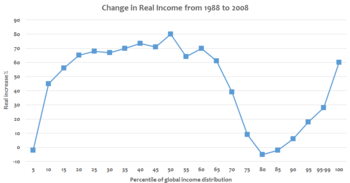

"Elephant curve": Change in real income between 1988 and 2008 at various income percentiles of global income distribution.

Trade liberalization may shift economic inequality from a global to a domestic scale.

When rich countries trade with poor countries, the low-skilled workers

in the rich countries may see reduced wages as a result of the

competition, while low-skilled workers in the poor countries may see

increased wages. Trade economist Paul Krugman estimates that trade

liberalisation has had a measurable effect on the rising inequality in the United States. He attributes this trend to increased trade with poor countries and the fragmentation of the means of production, resulting in low skilled jobs becoming more tradeable.

Anthropologist Jason Hickel contends that globalization and "structural adjustment" set off the "race to the bottom", a significant driver of surging global inequality. Another driver Hickel mentions is the debt system which advanced the need for structural adjustment in the first place.

Gender

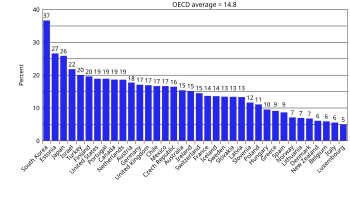

The gender gap in median earnings of full-time employees according to the

OECD 2015

In many countries, there is a gender pay gap in favor of males in the labor market.

Several factors other than discrimination contribute to this gap. On

average, women are more likely than men to consider factors other than

pay when looking for work, and may be less willing to travel or

relocate. Thomas Sowell, in his book Knowledge and Decisions,

claims that this difference is due to women not taking jobs due to

marriage or pregnancy. A U.S. Census's report stated that in US once

other factors are accounted for there is still a difference in earnings

between women and men.

Race

There is also a globally recognized disparity in the wealth, income, and economic welfare

of people of different races. In many nations, data exists to suggest

that members of certain racial demographics experience lower wages,

fewer opportunities for career and educational advancement, and intergenerational wealth gaps.

Studies have uncovered the emergence of what is called "ethnic

capital", by which people belonging to a race that has experienced

discrimination are born into a disadvantaged family from the beginning

and therefore have less resources and opportunities at their disposal. The universal lack of education, technical and cognitive skills, and

inheritable wealth within a particular race is often passed down between

generations, compounding in effect to make escaping these racialized cycles of poverty increasingly difficult.

Additionally, ethnic groups that experience significant disparities are

often also minorities, at least in representation though often in

number as well, in the nations where they experience the harshest

disadvantage. As a result, they are often segregated either by

government policy or social stratification, leading to ethnic

communities that experience widespread gaps in wealth and aid.

As a general rule, races which have been historically and

systematically colonized (typically indigenous ethnicities) continue to

experience lower levels of financial stability in the present day. The global South

is considered to be particularly victimized by this phenomenon, though

the exact socioeconomic manifestations change across different regions.

Westernized Nations

Even in economically developed societies with high levels of modernization

such as may be found in Western Europe, North America, and Australia,

minority ethnic groups and immigrant populations in particular

experience financial discrimination. While the progression of civil

rights movements and justice reform has improved access to education and

other economic opportunities in politically advanced nations, racial

income and wealth disparity still prove significant.

In the United States for example, which serves as a good basis for

understanding racial discrimination in the West due to the amount of

research attention it receives, a survey of African-American populations

show that they are more likely to drop out of high school and college,

are typically employed for fewer hours at lower wages, how lower than

average intergenerational wealth, and are more likely to use welfare as

young adults than their white counterparts.

Mexican-Americans, while suffering less debilitating socioeconomic

factors than black Americans, experience deficiencies in the same areas

when compared to whites and have not assimilated financially to the

level of stability experienced by white Americans as a whole.

These experiences are the effects of the measured disparity due to race

in countries like the US, where studies show that in comparison to

whites, blacks suffer from drastically lower levels of upward mobility,

higher levels of downward mobility, and poverty that is more easily

transmitted to offspring as a result of the disadvantage stemming from

the era of slavery and post-slavery racism that has been passed through racial generations to the present.

These are lasting financial inequalities that apply in varying

magnitudes to most non-white populations in nations such as the US, the

UK, France, Spain, Australia, etc.

Latin America

In

the countries of the Caribbean, Central America, and South America,

many ethnicities continue to deal with the effects fo European

colonization, and in general nonwhites tend to be noticeably poorer than

whites in this region. In many countries with significant populations

of indigenous races and those of Afro-descent (such as Mexico, Colombia,

Chile, etc.) income levels can be roughly half as high as those

experiences by white demographics, and this inequity is accompanied by

systematically unequal access to education, career opportunities, and

poverty relief. This region of the world, apart from urbanizing areas

like Brazil and Costa Rica, continues to be understudied and often the

racial disparity is denied by Latin Americans who consider themselves to

be living in post-racial and post-colonial societies far removed from

intense social and economic stratification despite the evidence to the

contrary.

Africa

African countries, too, continue to deal with the effects of the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade,

which set back economic development as a whole for blacks of African

citizenship more than any other region. The degree to which colonizers

stratified their holdings on the continent on the basis of race has had a

direct correlation in the magnitude of disparity experienced by

nonwhites in the nations that eventually rose from their colonial

status. Former French colonies, for example, see much higher rates of

income inequality between whites and nonwhites as a result of the rigid

hierarchy imposed by the French who lived in Africa at the time. Another prime example is found in South Africa, which, still reeling from the socioeconomic impacts of Apartheid, experiences some of the highest racial income and wealth inequality in all of Africa.

In these and other countries like Nigeria, Zimbabwe, and Sierra Leone,

movements of civil reform have initially led to improved access to

financial advancement opportunities, but data actually shows that for

nonwhites this progress is either stalling or erasing itself in the

newest generation of blacks that seek education and improved

transgenerational wealth. The economic status of one's parents continues

to define and predict the financial futures of African and minority

ethnic groups.

Asia

Asian regions

and countries such as China, the Middle East, and Central Asia have

been vastly understudied in terms of racial disparity, but even here the

effects of Western colonization provide similar results to those found

in other parts of the globe. Additionally, cultural and historical practices such as the caste system

in India leave their marks as well. While the disparity is greatly

improving in the case of India, there still exists social stratification

between peoples of lighter and darker skin tones that cumulatively

result in income and wealth inequality, manifesting in many of the same

poverty traps seen elsewhere.

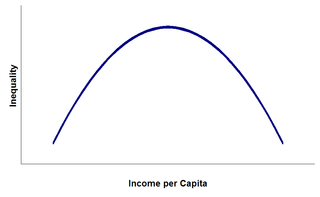

Economic development

Economist Simon Kuznets argued that levels of economic inequality are in large part the result of stages of development.

According to Kuznets, countries with low levels of development have

relatively equal distributions of wealth. As a country develops, it

acquires more capital, which leads to the owners of this capital having

more wealth and income and introducing inequality. Eventually, through

various possible redistribution mechanisms such as social welfare programs, more developed countries move back to lower levels of inequality.

Andranik Tangian

argues that the growing productivity due to advanced technologies

results in increasing wages' purchase power for most commodities, which

enables employers underpay workers in "labor equivalents", maintaining

nevertheless an impression of fair pay. This illusion is dismanteled by

the wages' decreasing purchase power for the commodities with a

significant share of hand labor. This difference between the appropriate

and factual pay goes to enterprise owners and top earners, increasing

the inequality.

Wealth concentration

As of 2019,

Jeff Bezos is the richest person in the world.

Wealth concentration is the process by which, under certain conditions, newly created wealth

concentrates in the possession of already-wealthy individuals or

entities. Accordingly, those who already hold wealth have the means to invest

in new sources of creating wealth or to otherwise leverage the

accumulation of wealth, and thus they are the beneficiaries of the new

wealth. Over time, wealth concentration can significantly contribute to

the persistence of inequality within society. Thomas Piketty in his book

Capital in the Twenty-First Century

argues that the fundamental force for divergence is the usually greater

return of capital (r) than economic growth (g), and that larger

fortunes generate higher returns.

According to a 2020 study by the RAND Corporation, the top 1% of U.S. income earners have taken $50 trillion from the bottom 90% between 1975 and 2018.

Rent seeking

Economist Joseph Stiglitz

argues that rather than explaining concentrations of wealth and income,

market forces should serve as a brake on such concentration, which may

better be explained by the non-market force known as "rent-seeking".

While the market will bid up compensation for rare and desired skills

to reward wealth creation, greater productivity, etc., it will also

prevent successful entrepreneurs from earning excess profits by

fostering competition to cut prices, profits and large compensation.

A better explainer of growing inequality, according to Stiglitz, is the

use of political power generated by wealth by certain groups to shape

government policies financially beneficial to them. This process, known

to economists as rent-seeking,

brings income not from creation of wealth but from "grabbing a larger

share of the wealth that would otherwise have been produced without

their effort"

Finance industry

Jamie Galbraith argues that countries with larger financial sectors have greater inequality, and the link is not an accident.

Global warming

A 2019 study published in PNAS found that global warming

plays a role in increasing economic inequality between countries,

boosting economic growth in developed countries while hampering such

growth in developing nations of the Global South. The study says that 25% of gap between the developed world and the developing world can be attributed to global warming.

A 2020 report by Oxfam and the Stockholm Environment Institute

says that the wealthiest 10% of the global population were responsible

for more than half of global carbon dioxide emissions from 1990 to 2015,

which increased by 60%. According to a 2020 report by the UNEP, overconsumption by the rich is a significant driver of the climate crisis,

and the wealthiest 1% of the world's population are responsible for

more than double the greenhouse gas emissions of the poorest 50%

combined. Inger Andersen,

in the foreword to the report, said "this elite will need to reduce

their footprint by a factor of 30 to stay in line with the Paris

Agreement targets."

Mitigating factors

Countries with a left-leaning legislature generally have lower levels of inequality.

Many factors constrain economic inequality – they may be divided into

two classes: government sponsored, and market driven. The relative

merits and effectiveness of each approach is a subject of debate.

Typical government initiatives to reduce economic inequality include:

- Public education: increasing the supply of skilled labor and reducing income inequality due to education differentials.

- Progressive taxation:

the rich are taxed proportionally more than the poor, reducing the

amount of income inequality in society if the change in taxation does

not cause changes in income.

Market forces outside of government intervention that can reduce economic inequality include:

- propensity to spend:

with rising wealth & income, a person may spend more. In an extreme

example, if one person owned everything, they would immediately need to

hire people to maintain their properties, thus reducing the wealth concentration. On the other hand, high-income persons have higher propensity to save.

Robin Maialeh then shows that increasing economic wealth decreases

propensity to spend and increases propensity to invest which

consequently leads to even greater growth rate of already rich agents.

Research shows that since 1300, the only periods with significant declines in wealth inequality in Europe were the Black Death and the two World Wars. Historian Walter Scheidel posits that, since the stone age, only extreme violence, catastrophes and upheaval in the form of total war, Communist revolution, pestilence and state collapse have significantly reduced inequality.

He has stated that "only all-out thermonuclear war might fundamentally

reset the existing distribution of resources" and that "peaceful policy

reform may well prove unequal to the growing challenges ahead."

Effects

A lot of research has been done about the effects of economic inequality on different aspects in society:

- Health: British researchers Richard G. Wilkinson and Kate Pickett have found higher rates of health and social problems (obesity, mental illness, homicides, teenage births, incarceration, child conflict, drug use) in countries and states with higher inequality. Some studies link a surge in "deaths of despair", suicide, drug overdoses and alcohol related deaths, to widening income inequality.

- Social goods: British researchers Richard G. Wilkinson and Kate Pickett have found lower rates of social goods (life expectancy by country, educational performance, trust among strangers, women's status, social mobility, even numbers of patents issued) in countries and states with higher inequality.

- Social cohesion: Research has shown an inverse link between

income inequality and social cohesion. In more equal societies, people

are much more likely to trust each other, measures of social capital

(the benefits of goodwill, fellowship, mutual sympathy and social

connectedness among groups who make up a social units) suggest greater

community involvement.

- Crime: In more equal societies homicide rates are consistently lower. A 2016 study finds that interregional inequality increases terrorism.

- Welfare: Studies have found evidence that in societies where

inequality is lower, population-wide satisfaction and happiness tend to

be higher.

- Debt: Income inequality has been the driving factor in the growing household debt,

as high earners bid up the price of real estate and middle income

earners go deeper into debt trying to maintain what once was a middle

class lifestyle.

- Economic growth: A 2016 meta-analysis found that "the effect

of inequality on growth is negative and more pronounced in less

developed countries than in rich countries". The study also found that

wealth inequality is more pernicious to growth than income inequality.

- Civic participation: Higher income inequality led to less of all forms of social, cultural, and civic participation among the less wealthy.

- Political instability: Studies indicate that economic

inequality leads to greater political instability, including an

increased risk of democratic breakdown and civil conflict.

- Political party responses: One study finds that economic

inequality prompts attempts by left-leaning politicians to pursue

redistributive policies while right-leaning politicians seek to repress

the redistributive policies.

Perspectives

Fairness vs. equality

According

to Christina Starmans et al. (Nature Hum. Beh., 2017), the research

literature contains no evidence on people having an aversion on

inequality. In all studies analyzed, the subjects preferred fair

distributions to equal distributions, in both laboratory and real-world

situations. In public, researchers may loosely speak of equality instead

of fairness, when referring to studies where fairness happens to

coincide with equality, but in many studies fairness is carefully

separated from equality and the results are univocal. Already very young

children seem to prefer fairness over equality.

When people were asked, what would be the wealth of each quintile

in their ideal society, they gave a 50-fold sum to the richest quintile

than to the poorest quintile. The preference for inequality increases

in adolescence, and so do the capabilities to favor fortune, effort and

ability in the distribution.

Preference for unequal distribution has been developed to the

human race possibly because it allows for better co-operation and allows

a person to work with a more productive person so that both parties

benefit from the co-operation. Inequality is also said to be able to

solve the problems of free-riders, cheaters and ill-behaving people,

although this is heavily debated.

Researches demonstrate that people usually underestimate the level of

actual inequality, which is also much higher than their desired level of

inequality.

In many societies, such as the USSR, the distribution led to protests from wealthier landowners.

In the current U.S., many feel that the distribution is unfair in being

too unequal. In both cases, the cause is unfairness, not inequality,

the researchers conclude.

Socialist perspectives

Socialists attribute the vast disparities in wealth to the private ownership of the means of production by a class of owners, creating a situation where a small portion of the population lives off unearned property income

by virtue of ownership titles in capital equipment, financial assets

and corporate stock. By contrast, the vast majority of the population is

dependent on income in the form of a wage or salary. In order to

rectify this situation, socialists argue that the means of production

should be socially owned so that income differentials would be reflective of individual contributions to the social product.

Marxist socialists ultimately predict the emergence of a communist society

based on the common ownership of the means of production, where each

individual citizen would have free access to the articles of consumption

(From each according to his ability, to each according to his need).

According to Marxist philosophy, equality in the sense of free access

is essential for freeing individuals from dependent relationships,

thereby allowing them to transcend alienation.

Meritocracy

Meritocracy

favors an eventual society where an individual's success is a direct

function of his merit, or contribution. Economic inequality would be a

natural consequence of the wide range in individual skill, talent and

effort in human population. David Landes stated that the progression of Western economic development that led to the Industrial Revolution was facilitated by men advancing through their own merit rather than because of family or political connections.

Liberal perspectives

Most modern social liberals,

including centrist or left-of-center political groups, believe that the

capitalist economic system should be fundamentally preserved, but the

status quo regarding the income gap must be reformed. Social liberals

favor a capitalist system with active Keynesian

macroeconomic policies and progressive taxation (to even out

differences in income inequality). Research indicates that people who

hold liberal beliefs tend to see greater income inequality as morally

wrong.

However, contemporary classical liberals and libertarians generally do not take a stance on wealth inequality, but believe in equality under the law regardless of whether it leads to unequal wealth distribution. In 1966 Ludwig von Mises, a prominent figure in the Austrian School of economic thought, explains:

The liberal champions of equality under the law were

fully aware of the fact that men are born unequal and that it is

precisely their inequality that generates social cooperation and

civilization. Equality under the law was in their opinion not designed

to correct the inexorable facts of the universe and to make natural

inequality disappear. It was, on the contrary, the device to secure for

the whole of mankind the maximum of benefits it can derive from it.

Henceforth no man-made institutions should prevent a man from attaining

that station in which he can best serve his fellow citizens.

Robert Nozick

argued that government redistributes wealth by force (usually in the

form of taxation), and that the ideal moral society would be one where

all individuals are free from force. However, Nozick recognized that

some modern economic inequalities were the result of forceful taking of

property, and a certain amount of redistribution would be justified to

compensate for this force but not because of the inequalities

themselves. John Rawls argued in A Theory of Justice

that inequalities in the distribution of wealth are only justified when

they improve society as a whole, including the poorest members. Rawls

does not discuss the full implications of his theory of justice. Some

see Rawls's argument as a justification for capitalism

since even the poorest members of society theoretically benefit from

increased innovations under capitalism; others believe only a strong welfare state can satisfy Rawls's theory of justice.

Classical liberal Milton Friedman

believed that if government action is taken in pursuit of economic

equality then political freedom would suffer. In a famous quote, he

said:

A society that puts equality before freedom will get

neither. A society that puts freedom before equality will get a high

degree of both.

Economist Tyler Cowen

has argued that though income inequality has increased within nations,

globally it has fallen over the 20 years leading up to 2014. He argues

that though income inequality may make individual nations worse off,

overall, the world has improved as global inequality has been reduced.

Social justice arguments

Patrick Diamond and Anthony Giddens (professors of Economics and Sociology, respectively) hold that 'pure meritocracy

is incoherent because, without redistribution, one generation's

successful individuals would become the next generation's embedded

caste, hoarding the wealth they had accumulated'.

They also state that social justice

requires redistribution of high incomes and large concentrations of

wealth in a way that spreads it more widely, in order to "recognise the

contribution made by all sections of the community to building the

nation's wealth." (Patrick Diamond and Anthony Giddens, June 27, 2005, New Statesman)

Pope Francis stated in his Evangelii gaudium,

that "as long as the problems of the poor are not radically resolved by

rejecting the absolute autonomy of markets and financial speculation

and by attacking the structural causes of inequality, no solution will

be found for the world's problems or, for that matter, to any problems." He later declared that "inequality is the root of social evil."

When income inequality is low, aggregate demand will be relatively high, because more people who want ordinary consumer goods and services will be able to afford them, while the labor force will not be as relatively monopolized by the wealthy.

Effects on social welfare

In most western democracies, the desire to eliminate or reduce economic inequality is generally associated with the political left. One practical argument in favor of reduction is the idea that economic inequality reduces social cohesion and increases social unrest, thereby weakening the society. There is evidence that this is true (see inequity aversion) and it is intuitive, at least for small face-to-face groups of people. Alberto Alesina, Rafael Di Tella, and Robert MacCulloch find that inequality negatively affects happiness in Europe but not in the United States.

It has also been argued that economic inequality invariably

translates to political inequality, which further aggravates the

problem. Even in cases where an increase in economic inequality makes

nobody economically poorer, an increased inequality of resources is

disadvantageous, as increased economic inequality can lead to a power

shift due to an increased inequality in the ability to participate in

democratic processes.

Capabilities approach

The capabilities approach – sometimes called the human development

approach – looks at income inequality and poverty as form of "capability

deprivation". Unlike neoliberalism,

which "defines well-being as utility maximization", economic growth and

income are considered a means to an end rather than the end itself. Its goal is to "wid[en] people's choices and the level of their achieved well-being"

through increasing functionings (the things a person values doing),

capabilities (the freedom to enjoy functionings) and agency (the ability

to pursue valued goals).

When a person's capabilities are lowered, they are in some way

deprived of earning as much income as they would otherwise. An old, ill

man cannot earn as much as a healthy young man; gender roles

and customs may prevent a woman from receiving an education or working

outside the home. There may be an epidemic that causes widespread panic,

or there could be rampant violence in the area that prevents people

from going to work for fear of their lives.

As a result, income inequality increases, and it becomes more difficult

to reduce the gap without additional aid. To prevent such inequality,

this approach believes it is important to have political freedom,

economic facilities, social opportunities, transparency guarantees, and

protective security to ensure that people aren't denied their

functionings, capabilities, and agency and can thus work towards a

better relevant income.

Policy responses intended to mitigate

A 2011 OECD study makes a number of suggestions to its member countries, including:

- Well-targeted income-support policies.

- Facilitation and encouragement of access to employment.

- Better job-related training and education for the low-skilled (on-the-job training) would help to boost their productivity potential and future earnings.

- Better access to formal education.

Progressive taxation reduces absolute income inequality when the higher rates on higher-income individuals are paid and not evaded, and transfer payments and social safety nets result in progressive government spending. Wage ratio legislation has also been proposed as a means of reducing income inequality. The OECD asserts that public spending is vital in reducing the ever-expanding wealth gap.

The economists Emmanuel Saez and Thomas Piketty recommend much higher top marginal tax rates on the wealthy, up to 50 percent, 70 percent or even 90 percent. Ralph Nader, Jeffrey Sachs, the United Front Against Austerity, among others, call for a financial transactions tax (also known as the Robin Hood tax) to bolster the social safety net and the public sector.

The Economist

wrote in December 2013: "A minimum wage, providing it is not set too

high, could thus boost pay with no ill effects on jobs....America's

federal minimum wage, at 38% of median income, is one of the rich

world's lowest. Some studies find no harm to employment from federal or

state minimum wages, others see a small one, but none finds any serious

damage."

General limitations on and taxation of rent-seeking are popular across the political spectrum.

Public policy responses addressing causes and effects of income inequality in the US include: progressive tax incidence adjustments, strengthening social safety net provisions such as Aid to Families with Dependent Children, welfare, the food stamp program, Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid, organizing community interest groups, increasing and reforming higher education subsidies, increasing infrastructure spending, and placing limits on and taxing rent-seeking.

A 2017 study in the Journal of Political Economy by Daron Acemoglu, James Robinson

and Thierry Verdier argues that American "cutthroat" capitalism and

inequality gives rise to technology and innovation that more "cuddly"

forms of capitalism cannot.

As a result, "the diversity of institutions we observe among relatively

advanced countries, ranging from greater inequality and risk-taking in

the United States to the more egalitarian societies supported by a

strong safety net in Scandinavia, rather than reflecting differences in

fundamentals between the citizens of these societies, may emerge as a

mutually self-reinforcing world equilibrium. If so, in this equilibrium,

'we cannot all be like the Scandinavians,' because Scandinavian capitalism depends in part on the knowledge spillovers created by the more cutthroat American capitalism." A 2012 working paper by the same authors, making similar arguments, was challenged by Lane Kenworthy,

who posited that, among other things, the Nordic countries are

consistently ranked as some of the world's most innovative countries by

the World Economic Forum's Global Competitiveness Index, with Sweden ranking as the most innovative nation, followed by Finland, for 2012–2013; the U.S. ranked sixth.

There are however global initiative like the United Nations Sustainable Development Goal 10 which aims to garner international efforts in reducing economic inequality considerably by 2030.