Anti-psychiatry, sometimes spelled antipsychiatry, is a movement based on the view that psychiatric treatment can often be more damaging than helpful to patients. The term anti-psychiatry was coined in 1912, and the movement emerged in the 1960s, highlighting controversies about psychiatry. Objections include the reliability of psychiatric diagnosis, the questionable effectiveness and harm associated with psychiatric medications, the failure of psychiatry to demonstrate any disease treatment mechanism for psychiatric medication effects, and legal concerns about equal human rights and civil freedom being nullified by the presence of diagnosis. Historical critiques of psychiatry came to light after focus on the extreme harms associated with electroconvulsive therapy and insulin shock therapy. The term "anti-psychiatry" is in dispute and often used to dismiss all critics of psychiatry, many of whom agree that a specialized role of helper for people in emotional distress may at times be appropriate, and allow for individual choice around treatment decisions.

Beyond concerns about effectiveness, anti-psychiatry might question the philosophical and ethical underpinnings of psychotherapy and psychoactive medication, seeing them as shaped by social and political concerns rather than the autonomy and integrity of the individual mind. They may believe that "judgements on matters of sanity should be the prerogative of the philosophical mind", and that the mind should not be a medical concern. Some activists reject the psychiatric notion of mental illness. Anti-psychiatry considers psychiatry a coercive instrument of oppression due to an unequal power relationship between doctor, therapist, and patient or client, and a highly subjective diagnostic process. Involuntary commitment, which can be enforced legally through sectioning, is an important issue in the movement. When sectioned, involuntary treatment may also be legally enforced by the medical profession against the patient's will.

The decentralized movement has been active in various forms for two centuries. In the 1960s, there were many challenges to psychoanalysis and mainstream psychiatry, in which the very basis of psychiatric practice was characterized as repressive and controlling. Psychiatrists identified with the anti-psychiatry movement included Timothy Leary, R. D. Laing, Franco Basaglia, Theodore Lidz, Silvano Arieti, and David Cooper. Others involved were Michel Foucault, Gilles Deleuze, Félix Guattari, and Erving Goffman. Cooper used the term "anti-psychiatry" in 1967, and wrote the book Psychiatry and Anti-psychiatry in 1971. The word Antipsychiatrie was already used in Germany in 1904. Thomas Szasz introduced the idea of mental illness being a myth in the book The Myth of Mental Illness (1961). However, his literature actually very clearly states that he was directly undermined by the movement led by David Cooper (1931–1986) and that Cooper sought to replace psychiatry with his own brand of it. Giorgio Antonucci, who advocated a non-psychiatric approach to psychological suffering, did not consider himself to be part of the antipsychiatric movement. His position is represented by "the non-psychiatric thinking, which considers psychiatry an ideology devoid of scientific content, a non-knowledge, whose aim is to annihilate people instead of trying to understand the difficulties of life, both individual and social, and then to defend people, change society, and create a truly new culture". Antonucci introduced the definition of psychiatry as a prejudice in the book I pregiudizi e la conoscenza critica alla psichiatria (1986).

The movement continues to influence thinking about psychiatry and psychology, both within and outside of those fields, particularly in terms of the relationship between providers of treatment and those receiving it. Contemporary issues include freedom versus coercion, nature versus nurture, and the right to be different.

Critics of antipsychiatry from within psychiatry itself object to the underlying principle that psychiatry is harmful, although they usually accept that there are issues that need addressing. Medical professionals often consider anti-psychiatry movements to be promoting mental illness denial, and some consider their claims to be comparable to conspiracy theories.

History

Precursors

The first widespread challenge to the prevailing medical approach in Western countries occurred in the late 18th century. Part of the progressive Age of Enlightenment, a "moral treatment" movement challenged the harsh, pessimistic, somatic (body-based) and restraint-based approaches that prevailed in the system of hospitals and "madhouses" for people considered mentally disturbed, who were generally seen as wild animals without reason. Alternatives were developed, led in different regions by ex-patient staff, physicians themselves in some cases, and religious and lay philanthropists. This "moral treatment" was seen as pioneering more humane psychological and social approaches, whether or not in medical settings; however, it also involved some use of physical restraints, threats of punishment, and personal and social methods of control. As it became the establishment approach in the 19th century, opposition to its negative aspects also grew.

According to Michel Foucault, there was a shift in the perception of madness, whereby it came to be seen as less about delusion, i.e. disturbed judgment about the truth, than about a disorder of regular, normal behavior or will. Foucault argued that, prior to this, doctors could often prescribe travel, rest, walking, retirement and generally engaging with nature, seen as the visible form of truth, as a means to break with artificialities of the world (and therefore delusions). Another form of treatment involved nature's opposite, the theater, where the patient's madness was acted out for him or her in such a way that the delusion would reveal itself to the patient.

Thus the most prominent therapeutic technique became to confront patients with a healthy sound will and orthodox passions, ideally embodied by the physician. The "cure" involved a process of opposition, of struggle and domination, of the patient's troubled will by the healthy will of the physician. It was thought the confrontation would lead not only to bring the illness into broad daylight by its resistance, but also to the victory of the sound will and the renunciation of the disturbed will. We must apply a perturbing method, to break the spasm by means of the spasm.... We must subjugate the whole character of some patients, subdue their transports, break their pride, while we must stimulate and encourage the others (Esquirol, J. E. D., 1816). Foucault also argued that the increasing internment of the "mentally ill" (the development of more and bigger asylums) had become necessary not just for diagnosis and classification but because an enclosed place became a requirement for a treatment that was now understood as primarily the contest of wills, a question of submission and victory.

The techniques and procedures of the asylums at this time included "isolation, private or public interrogations, punishment techniques such as cold showers, moral talks (encouragements or reprimands), strict discipline, compulsory work, rewards, preferential relations between the physician and his patients, relations of vassalage, of possession, of domesticity, even of servitude between patient and physician at times". Foucault summarized these as "designed to make the medical personage the 'master of madness'" through the power the physician's will exerts on the patient. The effect of this shift then served to inflate the power of the physician relative to the patient, correlated with the rapid rise of internment (asylums and forced detention).

Other analyses suggest that the rise of asylums was primarily driven by industrialization and capitalism, including the breakdown of traditional family structures. By the end of the 19th century, psychiatrists often had little power in the overcrowded asylum system, acting mainly as administrators who rarely attended to patients in a system where therapeutic ideals had turned into institutional routines. In general, critics point to negative aspects of the shift toward so-called "moral treatments", and the concurrent widespread expansion of asylums, medical power and involuntary hospitalization laws, that played an important part in the development of the anti-psychiatry movement.

Various 19th-century critiques of the newly emerging field of psychiatry overlap thematically with 20th-century anti-psychiatry, for example in their questioning of the medicalization of "madness". Those critiques occurred at a time when physicians had not yet achieved hegemony through psychiatry, however, so there was no single, unified force to oppose. Nevertheless, there was increasing concern at the ease with which people could be confined, with frequent reports of abuse and illegal confinement. For example, Daniel Defoe, the author of Robinson Crusoe, had previously argued for more government oversight of "madhouses" and for due process prior to involuntary internment. He later argued that husbands used asylum hospitals to incarcerate their disobedient wives, and in a subsequent pamphlet that wives even did the same to their husbands. It was also proposed that the role of asylum keeper be separated from doctor, to discourage exploitation of patients. There was general concern that physicians were undermining personhood by medicalizing problems, by claiming they alone had the expertise to judge, and by arguing that mental disorder was physical and hereditary. The Alleged Lunatics' Friend Society arose in England in the mid-19th century to challenge the system and campaign for rights and reforms. In the United States, Elizabeth Packard published a series of books and pamphlets describing her experiences in the Illinois insane asylum, to which she had been committed at the request of her husband.

Throughout, the class nature of mental hospitals and their role as agencies of control were well recognized. The new psychiatry was partially challenged by two powerful social institutions—the church and the legal system. These trends have been thematically linked to the later-20th-century anti-psychiatry movement.

As psychiatry became more professionally established during the 19th century (the term itself was coined in 1808 in Germany by Johann Christian Reil, as "Psychiaterie") and developed allegedly more invasive treatments, opposition increased. In the Southern US, black slaves and abolitionists encountered drapetomania, a pseudo-scientific diagnosis that presented the desire of slaves to run away from their masters as a symptom of pathology.

There was some organized challenge to psychiatry in the late 1870s from the new speciality of neurology, largely centered around control of state insane asylums in New York. Practitioners criticized mental hospitals for failure to conduct scientific research and adopt the modern therapeutic methods such as nonrestraint. Together with lay reformers and social workers, neurologists formed the National Association for the Protection of the Insane and the Prevention of Insanity. However, when the lay members questioned the competence of asylum physicians to even provide proper care at all, the neurologists withdrew their support and the association floundered.

Early 1900s

It has been noted that "the most persistent critics of psychiatry have always been former mental hospital patients", but that very few were able to tell their stories publicly or to confront the psychiatric establishment openly, and those who did so were commonly considered so extreme in their charges that they could seldom gain credibility. In the early 20th century, ex-patient Clifford W. Beers campaigned to improve the plight of individuals receiving public psychiatric care, particularly those committed to state institutions, publicizing the issues in his book, A Mind that Found Itself (1908). While Beers initially condemned psychiatrists for tolerating mistreatment of patients, and envisioned more ex-patient involvement in the movement, he was influenced by Adolf Meyer and the psychiatric establishment, and toned down his hostility since he needed their support for reforms. In Germany during this time were similar efforts which used the term "Antipsychiatrie".

Beers' reliance on rich donors and his need for approval from experts led him to hand over to psychiatrists the organization he helped found, the National Committee for Mental Hygiene, which eventually became the National Mental Health Association. In the UK, the National Society for Lunacy Law Reform was established in 1920 by angry ex-patients who sought justice for abuses committed in psychiatric custody, and were aggrieved that their complaints were patronizingly discounted by the authorities, who were seen to value the availability of medicalized internment as a 'whitewashed' extrajudicial custodial and punitive process. In 1922, ex-patient Rachel Grant-Smith added to calls for reform of the system of neglect and abuse she had suffered by publishing "The Experiences of an Asylum Patient". In the US, We Are Not Alone (WANA) was founded by a group of patients at Rockland State Hospital in New York, and continued to meet as an ex-patient group.

French surrealist Antonin Artaud would also openly criticize that no patient should be labeled as "mentally ill" as an exterior identification, as he notes in his 1925 L'Ombilic des limbes, as well as arguing against narcotic's restriction laws in France. Much influenced by the Dada and surrealist enthusiasms of the day, he considered dreams, thoughts and visions no less real than the "outside" world. In this era before penicillin was discovered, eugenics was popular. People believed diseases of the mind could be passed on so compulsory sterilization of the mentally ill was enacted in many countries.

1930s

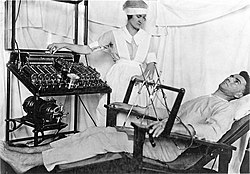

In the 1930s several controversial medical practices were introduced and framed as "treatments" for mental disorders, including inducing seizures (by electroshock, insulin or other drugs) or psychosurgery (lobotomy). In the US, beginning in 1939 through 1951, over 50,000 lobotomy operations were performed in mental hospitals, a procedure ultimately seen as inhumane.

Holocaust historians argued that the medicalization of social programs and systematic euthanasia of people in German mental institutions in the 1930s provided the institutional, procedural, and doctrinal origins of the mass murder of the 1940s. The Nazi programs were called Action T4 and Action 14f13. The Nuremberg Trials convicted a number of psychiatrists who held key positions in Nazi regimes. As one Swiss psychiatrist stated: "A not so easy question to be answered is whether it should be allowed to destroy lives objectively 'unworthy of living' without the expressed request of its bearers. (...) Even in incurable mentally ill ones suffering seriously from hallucinations and melancholic depressions and not being able to act, to a medical colleague I would ascript the right and in serious cases the duty to shorten—often for many years—the suffering" (Bleuler, Eugen, 1936: "Die naturwissenschaftliche Grundlage der Ethik". Schweizer Archiv Neurologie und Psychiatrie, Band 38, Nr.2, S. 206).

1940s and 1950s

The post-World War II decades saw an enormous growth in psychiatry; many Americans were persuaded that psychiatry and psychology, particularly psychoanalysis, were a key to happiness. Meanwhile, most hospitalized mental patients received at best decent custodial care, and at worst, abuse and neglect.

The psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan has been identified as an influence on later anti-psychiatry theory in the UK, and as being the first, in the 1940s and 50s, to professionally challenge psychoanalysis to reexamine its concepts and to appreciate psychosis as understandable. Other influences on Lacan included poetry and the surrealist movement, including the poetic power of patients' experiences. Critics disputed this and questioned how his descriptions linked to his practical work. The names that came to be associated with the anti-psychiatry movement knew of Lacan and acknowledged his contribution even if they did not entirely agree. The psychoanalyst Erich Fromm is also said to have articulated, in the 1950s, the secular humanistic concern of the coming anti-psychiatry movement. In The Sane Society (1955), Fromm wrote "An unhealthy society is one which creates mutual hostility [and] distrust, which transforms man into an instrument of use and exploitation for others, which deprives him of a sense of self, except inasmuch as he submits to others or becomes an automaton"..."Yet many psychiatrists and psychologists refuse to entertain the idea that society as a whole may be lacking in sanity. They hold that the problem of mental health in a society is only that of the number of 'unadjusted' individuals, and not of a possible unadjustment of the culture itself".

In the 1950s new psychiatric drugs, notably the antipsychotic chlorpromazine, slowly came into use. Although often accepted as an advance in some ways, there was opposition, partly due to serious adverse effects such as tardive dyskinesia, and partly due their "chemical straitjacket" effect and their alleged use to control and intimidate patients. Patients often opposed psychiatry and refused or stopped taking the drugs when not subject to psychiatric control. There was also increasing opposition to the large-scale use of psychiatric hospitals and institutions, and attempts were made to develop services in the community.

According to the Encyclopedia of Theory and Practice in Psychotherapy and Counseling, "In the 1950s in the United States, a right-wing anti-mental health movement opposed psychiatry, seeing it as liberal, left-wing, subversive and anti-American or pro-Communist. There were widespread fears that it threatened individual rights and undermined moral responsibility. An early skirmish was over the Alaska Mental Health Bill, where the right wing protestors were joined by the emerging Scientology movement."

The field of psychology sometimes came into opposition with psychiatry. Behaviorists argued that mental disorder was a matter of learning not medicine; for example, Hans Eysenck argued that psychiatry "really has no role to play". The developing field of clinical psychology in particular came into close contact with psychiatry, often in opposition to its methods, theories and territories.

1960s

Coming to the fore in the 1960s, "anti-psychiatry" (a term first used by David Cooper in 1967) defined a movement that vocally challenged the fundamental claims and practices of mainstream psychiatry. While most of its elements had precedents in earlier decades and centuries, in the 1960s it took on a national and international character, with access to the mass media and incorporating a wide mixture of grassroots activist organizations and prestigious professional bodies.

Cooper was a South African psychiatrist working in Britain. A trained Marxist revolutionary, he argued that the political context of psychiatry and its patients had to be highlighted and radically challenged, and warned that the fog of individualized therapeutic language could take away people's ability to see and challenge the bigger social picture. He spoke of having a goal of "non-psychiatry" as well as anti-psychiatry.

- In the 1960s fresh voices mounted a new challenge to the pretensions of psychiatry as a science and the mental health system as a successful humanitarian enterprise. These voices included: Ernest Becker, Erving Goffman, R.D. Laing; Laing and Aaron Esterson, Thomas Scheff, and Thomas Szasz. Their writings, along with others such as articles in the journal The Radical Therapist, were given the umbrella label "antipsychiatry" despite wide divergences in philosophy. This critical literature, in concert with an activist movement, emphasized the hegemony of medical model psychiatry, its spurious sources of authority, its mystification of human problems, and the more oppressive practices of the mental health system, such as involuntary hospitalisation, drugging, and electroshock.

The psychiatrists R D Laing (from Scotland), Theodore Lidz (from America), Silvano Arieti (from Italy) and others, argued that "schizophrenia" and psychosis were understandable, and resulted from injuries to the inner-self-inflicted by psychologically invasive "schizophrenogenic" parents or others. It was sometimes seen as a transformative state involving an attempt to cope with a sick society. Laing, however, partially dissociated himself from his colleague Cooper's term "anti-psychiatry". Laing had already become a media icon through bestselling books (such as The Divided Self and The Politics of Experience) discussing mental distress in an interpersonal existential context; Laing was somewhat less focused than his colleague Cooper on wider social structures and radical left wing politics, and went on to develop more romanticized or mystical views (as well as equivocating over the use of diagnosis, drugs and commitment). Although the movement originally described as anti-psychiatry became associated with the general counter-culture movement of the 1960s, Lidz and Arieti never became involved in the latter. Franco Basaglia promoted anti-psychiatry in Italy and secured reforms to mental health law there.

Laing, through the Philadelphia Association founded with Cooper in 1965, set up over 20 therapeutic communities including Kingsley Hall, where staff and residents theoretically assumed equal status and any medication used was voluntary. Non-psychiatric Soteria houses, starting in the United States, were also developed as were various ex-patient-led services.

Psychiatrist Thomas Szasz argued that "mental illness" is an inherently incoherent combination of a medical and a psychological concept. He opposed the use of psychiatry to forcibly detain, treat, or excuse what he saw as mere deviance from societal norms or moral conduct. As a libertarian, Szasz was concerned that such usage undermined personal rights and moral responsibility. Adherents of his views referred to "the myth of mental illness", after Szasz's controversial 1961 book of that name (based on a paper of the same name that Szasz had written in 1957 that, following repeated rejections from psychiatric journals, had been published in the American Psychologist in 1960). Although widely described as part of the main anti-psychiatry movement, Szasz actively rejected the term and its adherents; instead, in 1969, he collaborated with Scientology to form the Citizens Commission on Human Rights. It was later noted that the view that insanity was not in most or even in any instances a "medical" entity, but a moral issue, was also held by Christian Scientists and certain Protestant fundamentalists, as well as Szasz. Szasz was not a Scientologist himself and was non-religious; he commented frequently on the parallels between religion and psychiatry.

Erving Goffman, Gilles Deleuze, Félix Guattari and others criticized the power and role of psychiatry in society, including the use of "total institutions" and the use of models and terms that were seen as stigmatizing. The French sociologist and philosopher Foucault, in his 1961 publication Madness and Civilization: A History of Insanity in the Age of Reason, analyzed how attitudes towards those deemed "insane" had changed as a result of changes in social values. He argued that psychiatry was primarily a tool of social control, based historically on a "great confinement" of the insane and physical punishment and chains, later exchanged in the moral treatment era for psychological oppression and internalized restraint. American sociologist Thomas Scheff applied labeling theory to psychiatry in 1966 in "Being Mentally Ill". Scheff argued that society views certain actions as deviant and, in order to come to terms with and understand these actions, often places the label of mental illness on those who exhibit them. Certain expectations are then placed on these individuals and, over time, they unconsciously change their behavior to fulfill them.

Observation of the abuses of psychiatry in the Soviet Union in the so-called Psikhushka hospitals also led to questioning the validity of the practice of psychiatry in the West. In particular, the diagnosis of many political dissidents with schizophrenia led some to question the general diagnosis and punitive usage of the label schizophrenia. This raised questions as to whether the schizophrenia label and resulting involuntary psychiatric treatment could not have been similarly used in the West to subdue rebellious young people during family conflicts.

Since 1970

New professional approaches were developed as an alternative or reformist complement to psychiatry. The Radical Therapist, a journal begun in 1971 in North Dakota by Michael Glenn, David Bryan, Linda Bryan, Michael Galan and Sara Glenn, challenged the psychotherapy establishment in a number of ways, raising the slogan "Therapy means change, not adjustment." It contained articles that challenged the professional mediator approach, advocating instead revolutionary politics and authentic community making. Social work, humanistic or existentialist therapies, family therapy, counseling and self-help and clinical psychology developed and sometimes opposed psychiatry.

The psychoanalytically trained psychiatrist Szasz, although professing fundamental opposition to what he perceives as medicalization and oppressive or excuse-giving "diagnosis" and forced "treatment", was not opposed to other aspects of psychiatry (for example attempts to "cure-heal souls", although he also characterizes this as non-medical). Although generally considered anti-psychiatry by others, he sought to dissociate himself politically from a movement and term associated with the radical left wing. In a 1976 publication "Anti-psychiatry: The paradigm of a plundered mind", which has been described as an overtly political condemnation of a wide sweep of people, Szasz claimed Laing, Cooper and all of anti-psychiatry consisted of "self-declared socialists, communists, anarchists or at least anti-capitalists and collectivists". While saying he shared some of their critique of the psychiatric system, Szasz compared their views on the social causes of distress/deviance to those of anti-capitalist anti-colonialists who claimed that Chilean poverty was due to plundering by American companies, a comment Szasz made not long after a CIA-backed coup had deposed the democratically elected Chilean president and replaced him with Pinochet. Szasz argued instead that distress/deviance is due to the flaws or failures of individuals in their struggles in life.

The anti-psychiatry movement was also being driven by individuals with adverse experiences of psychiatric services. This included those who felt they had been harmed by psychiatry or who felt that they could have been helped more by other approaches, including those compulsorily (including via physical force) admitted to psychiatric institutions and subjected to compulsory medication or procedures. During the 1970s, the anti-psychiatry movement was involved in promoting restraint from many practices seen as psychiatric abuses.

The gay rights movement continued to challenge the classification of homosexuality as a mental illness and in 1974, in a climate of controversy and activism, the American Psychiatric Association membership (following a unanimous vote by the trustees in 1973) voted by a small majority (58%) to remove it as an illness category from the DSM, replacing it with a category of "sexual orientation disturbance" and then "ego-dystonic homosexuality," which was deleted in 1986, although a wide variety of "paraphilias" remain.

The diagnostic label gender identity disorder (GID) was used by the DSM until its reclassification as gender dysphoria in 2013, with the release of the DSM-5. The diagnosis was reclassified to better align it with medical understanding of the condition and to remove the stigma associated with the term disorder. The American Psychiatric Association, publisher of the DSM-5, stated that gender nonconformity is not the same thing as gender dysphoria, and that "gender nonconformity is not in itself a mental disorder. The critical element of gender dysphoria is the presence of clinically significant distress associated with the condition." Some transgender people and researchers support declassification of the condition because they say the diagnosis pathologizes gender variance and reinforces the binary model of gender. Szasz also publicly endorsed the transmisogynist work of Janice Raymond. In a 1979 New York Times book review of Raymond's The Transsexual Empire, Szasz drew connections between his ongoing critique of psychiatric diagnosis and Raymond's feminist critique of trans women.

Increased legal and professional protections, and a merging with human rights and disability rights movements, added to anti-psychiatry theory and action.

Anti-psychiatry came to challenge a "biomedical" focus of psychiatry (defined to mean genetics, neurochemicals and pharmaceutic drugs). There was also opposition to the increasing links between psychiatry and pharmaceutical companies, which were becoming more powerful and were increasingly claimed to have excessive, unjustified and underhand influence on psychiatric research and practice. There was also opposition to the codification of, and alleged misuse of, psychiatric diagnoses into manuals, in particular the American Psychiatric Association, which publishes the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders.

Anti-psychiatry increasingly challenged alleged psychiatric pessimism and institutionalized alienation regarding those categorized as mentally ill. An emerging consumer/survivor movement often argues for full recovery, empowerment, self-management and even full liberation. Schemes were developed to challenge stigma and discrimination, often based on a social model of disability; to assist or encourage people with mental health issues to engage more fully in work and society (for example through social firms), and to involve service users in the delivery and evaluation of mental health services. However, those actively and openly challenging the fundamental ethics and efficacy of mainstream psychiatric practice remained marginalized within psychiatry, and to a lesser extent within the wider mental health community.

Three authors came to personify the movement against psychiatry, and two of these were practicing psychiatrists. The initial and most influential of these was Thomas Szasz who rose to fame with his book The Myth of Mental Illness, although Szasz himself did not identify as an anti-psychiatrist. The well-respected R D Laing wrote a series of best-selling books, including The Divided Self. Intellectual philosopher Michel Foucault challenged the very basis of psychiatric practice and cast it as repressive and controlling. The term "anti-psychiatry" was coined by David Cooper in 1967. In parallel with the theoretical production of the mentioned authors, the Italian physician Giorgio Antonucci questioned the basis themselves of psychiatry through the dismantling of the psychiatric hospitals Osservanza and Luigi Lolli and the liberation—and restitution to life—of the people there secluded.

Challenges to psychiatry

Civilization as a cause of distress

In recent years, psychotherapists David Smail and Bruce E. Levine, considered part of the anti-psychiatry movement, have written widely on how society, culture, politics and psychology intersect. They have written extensively of the "embodied nature" of the individual in society, and the unwillingness of even therapists to acknowledge the obvious part played by power and financial interest in modern Western society. They argue that feelings and emotions are not, as is commonly supposed, features of the individual, but rather responses of the individual to their situation in society. Even psychotherapy, they suggest, can only change feelings in as much as it helps a person to change the "proximal" and "distal" influences on their life, which range from family and friends, to the workplace, socio-economics, politics and culture.

R. D. Laing emphasized family nexus as a mechanism by which individuals become victimized by those around them, and spoke about a dysfunctional society.

Inadequacy of clinical interviews used to diagnose 'diseases'

Psychiatrists have been trying to differentiate mental disorders based on clinical interviews since the era of Kraepelin, but now realize that their diagnostic criteria are imperfect. Tadafumi Kato writes, "We psychiatrists should be aware that we cannot identify 'diseases' only by interviews. What we are doing now is just like trying to diagnose diabetes mellitus without measuring blood sugar."

Normality and illness judgments

In 2013, psychiatrist Allen Frances said that "psychiatric diagnosis still relies exclusively on fallible subjective judgments rather than objective biological tests".

Reasons have been put forward to doubt the ontic status of mental disorders. Mental disorders engender ontological skepticism on three levels:

- Mental disorders are abstract entities that cannot be directly appreciated with the human senses or indirectly, as one might with macro- or microscopic objects.

- Mental disorders are not clearly natural processes whose detection is untarnished by the imposition of values, or human interpretation.

- It is unclear whether they should be conceived as abstractions that exist in the world apart from the individual persons who experience them, and thus instantiate them.

In the scientific and academic literature on the definition or classification of mental disorder, one extreme argues that it is entirely a matter of value judgements (including of what is normal) while another proposes that it is or could be entirely objective and scientific (including by reference to statistical norms). Common hybrid views argue that the concept of mental disorder is objective but a "fuzzy prototype" that can never be precisely defined, or alternatively that it inevitably involves a mix of scientific facts and subjective value judgments.

One remarkable example of psychiatric diagnosis being used to reinforce cultural bias and oppress dissidence is the diagnosis of drapetomania. In the US prior to the American Civil War, physicians such as Samuel A. Cartwright diagnosed some slaves with drapetomania, a mental illness in which the slave possessed an irrational desire for freedom and a tendency to try to escape. By classifying such a dissident mental trait as abnormal and a disease, psychiatry promoted cultural bias about normality, abnormality, health, and unhealth. This example indicates the probability for not only cultural bias but also confirmation bias and bias blind spot in psychiatric diagnosis and psychiatric beliefs.

It has been argued by philosophers like Foucault that characterizations of "mental illness" are indeterminate and reflect the hierarchical structures of the societies from which they emerge rather than any precisely defined qualities that distinguish a "healthy" mind from a "sick" one. Furthermore, if a tendency toward self-harm is taken as an elementary symptom of mental illness, then humans, as a species, are arguably insane in that they have tended throughout recorded history to destroy their own environments, to make war with one another, etc.

Psychiatric labeling

Mental disorders were first included in the sixth revision of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-6) in 1949. Three years later, the American Psychiatric Association created its own classification system, DSM-I. The definitions of most psychiatric diagnoses consist of combinations of phenomenological criteria, such as symptoms and signs and their course over time. Expert committees combined them in variable ways into categories of mental disorders, defined and redefined them again and again over the last half century.

The majority of these diagnostic categories are called disorders and are not validated by biological criteria, as most medical diseases are; although they purport to represent medical diseases and take the form of medical diagnoses. These diagnostic categories are actually embedded in top-down classifications, similar to the early botanic classifications of plants in the 17th and 18th centuries, when experts decided a priori about which classification criterion to use, for instance, whether the shape of leaves or fruiting bodies were the main criterion for classifying plants. Since the era of Kraepelin, psychiatrists have been trying to differentiate mental disorders by using clinical interviews.

Experiments admitting "healthy" individuals into psychiatric care

In 1972, psychologist David Rosenhan published the Rosenhan experiment, a study questioning the validity of psychiatric diagnoses. The study arranged for eight individuals with no history of psychopathology to attempt admission into psychiatric hospitals. The individuals included a graduate student, psychologists, an artist, a housewife, and two physicians, including one psychiatrist. All eight individuals were admitted with a diagnosis of schizophrenia or bipolar disorder. Psychiatrists then attempted to treat the individuals using psychiatric medication. All eight were discharged within 7 to 52 days. In a later part of the study, psychiatric staff were warned that pseudo-patients might be sent to their institutions, but none were actually sent. Nevertheless, a total of 83 patients out of 193 were believed by at least one staff member to be actors. The study concluded that individuals without mental disorders were indistinguishable from those with mental disorders.

Critics such as Robert Spitzer cast doubt on the validity and credibility of the study, but did concede that the consistency of psychiatric diagnoses needed improvement. The challenge of the validity versus the reliability of diagnostic categories continues to plague diagnostic systems. Neuroscientist Tadafumi Kato advocates for a new classification of diseases based on the neurobiological features of each mental disorder. while Austrian psychiatrist Heinz Katsching advises psychiatrists to replace the term "mental illness" by "brain illness."

There are recognized problems regarding the diagnostic reliability and validity of mainstream psychiatric diagnoses, both in ideal and controlled circumstances and even more so in routine clinical practice (McGorry et al.. 1995). Criteria in the principal diagnostic manuals, the DSM and ICD, are not consistent between the two manuals. Some psychiatrists in critiquing diagnostic criteria point out that comorbidity, when an individual meets criteria for two or more disorders, is the rule rather than the exception, casting doubt on the distinctness of the categories, with overlap and vaguely defined or changeable boundaries between what are asserted to be distinct disorders.

Other concerns raised include using standard diagnostic criteria in different countries, cultures, genders or ethnic groups. Critics contend that Westernized, white, male-dominated psychiatric practices and diagnoses disadvantage and misunderstand those from other groups. For example, several studies have shown that African Americans are more often diagnosed with schizophrenia than white people, and men more than women. Some within the anti-psychiatry movement are critical of the use of diagnosis at all as it conforms with the biomedical model, seen as illegitimate.

Tool of social control

According to Franco Basaglia, Giorgio Antonucci, and Bruce E. Levine, whose approach pointed out the role of psychiatric institutions in the control and medicalization of deviant behaviors and social problems, psychiatry is used as the provider of scientific support for social control to the existing establishment, and the ensuing standards of deviance and normality brought about repressive views of discrete social groups. According to Mike Fitzpatrick, resistance to medicalization was a common theme of the gay liberation, anti-psychiatry, and feminist movements of the 1970s, but now there is actually no resistance to the advance of government intrusion in lifestyle if it is thought to be justified in terms of public health.

In the opinion of Mike Fitzpatrick, the pressure for medicalization also comes from society itself. As one example, Fitzpatrick claims that feminists who once opposed state intervention as oppressive and patriarchal, now demand more coercive and intrusive measures to deal with child abuse and domestic violence. According to Richard Gosden, the use of psychiatry as a tool of social control is becoming obvious in preventive medicine programs for various mental diseases. These programs are intended to identify children and young people with divergent behavioral patterns and thinking and send them to treatment before their supposed mental diseases develop. Clinical guidelines for best practice in Australia include the risk factors and signs which can be used to detect young people who are in need of prophylactic drug treatment to prevent the development of schizophrenia and other psychotic conditions.

Psychiatry and the pharmaceutical industry

Critics of psychiatry commonly express a concern that the path of diagnosis and treatment in contemporary society is primarily or overwhelmingly shaped by profit prerogatives, echoing a common criticism of general medical practice in the United States, where many of the largest psychopharmaceutical producers are based.

Psychiatric research has demonstrated varying degrees of efficacy for improving or managing a number of mental health disorders through either medications, psychotherapy, or a combination of the two. Typical psychiatric medications include stimulants, antidepressants, anxiolytics, and antipsychotics (neuroleptics).

On the other hand, organizations such as MindFreedom International and World Network of Users and Survivors of Psychiatry maintain that psychiatrists exaggerate the evidence of medication and minimize the evidence of adverse drug reaction. They and other activists believe individuals are not given balanced information, and that current psychiatric medications do not appear to be specific to particular disorders in the way mainstream psychiatry asserts; and psychiatric drugs not only fail to correct measurable chemical imbalances in the brain, but rather induce undesirable side effects. For example, though children on Ritalin and other psycho-stimulants become more obedient to parents and teachers, critics have noted that they can also develop abnormal movements such as tics, spasms and other involuntary movements. This has not been shown to be directly related to the therapeutic use of stimulants, but to neuroleptics. The diagnosis of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder on the basis of inattention to compulsory schooling also raises critics' concerns regarding the use of psychoactive drugs as a means of unjust social control of children.

The influence of pharmaceutical companies is another major issue for the anti-psychiatry movement. As many critics from within and outside of psychiatry have argued, there are many financial and professional links between psychiatry, regulators, and pharmaceutical companies. Drug companies routinely fund much of the research conducted by psychiatrists, advertise medication in psychiatric journals and conferences, fund psychiatric and healthcare organizations and health promotion campaigns, and send representatives to lobby general physicians and politicians. Peter Breggin, Sharkey, and other investigators of the psycho-pharmaceutical industry maintain that many psychiatrists are members, shareholders or special advisors to pharmaceutical or associated regulatory organizations.

There is evidence that research findings and the prescribing of drugs are influenced as a result. A United Kingdom cross-party parliamentary inquiry into the influence of the pharmaceutical industry in 2005 concludes: "The influence of the pharmaceutical industry is such that it dominates clinical practice" and that there are serious regulatory failings resulting in "the unsafe use of drugs; and the increasing medicalization of society". The campaign organization No Free Lunch details the prevalent acceptance by medical professionals of free gifts from pharmaceutical companies and the effect on psychiatric practice. The ghostwriting of articles by pharmaceutical company officials, which are then presented by esteemed psychiatrists, has also been highlighted. Systematic reviews have found that trials of psychiatric drugs that are conducted with pharmaceutical funding are several times more likely to report positive findings than studies without such funding.

The number of psychiatric drug prescriptions have been increasing at an extremely high rate since the 1950s and show no sign of abating. In the United States antidepressants and tranquilizers are now the top selling class of prescription drugs, and neuroleptics and other psychiatric drugs also rank near the top, all with expanding sales. As a solution to the apparent conflict of interests, critics propose legislation to separate the pharmaceutical industry from the psychiatric profession.

John Read and Bruce E. Levine have advanced the idea of socioeconomic status as a significant factor in the development and prevention of mental disorders such as schizophrenia and have noted the reach of pharmaceutical companies through industry sponsored websites as promoting a more biological approach to mental disorders, rather than a comprehensive biological, psychological and social model.

Electroconvulsive therapy

Psychiatrists may advocate psychiatric drugs, psychotherapy or more controversial interventions such as electroshock or psychosurgery to treat mental illness. Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) is administered worldwide typically for severe mental disorders. Across the globe it has been estimated that approximately 1 million patients receive ECT per year. Exact numbers of how many persons per year have ECT in the United States are unknown due to the variability of settings and treatment. Researchers' estimates generally range from 100,000 to 200,000 persons per year.

Some persons receiving ECT die during the procedure (ECT is performed under a general anesthetic, which always carries a risk). Leonard Roy Frank writes that estimates of ECT-related death rates vary widely. The lower estimates include:

- 2–4 in 100,000 (from Kramer's 1994 study of 28,437 patients)

- 1 in 10,000 (Boodman's first entry in 1996)

- 1 in 1,000 (Impastato's first entry in 1957)

- 1 in 200, among the elderly, over 60 (Impastato's in 1957)

Higher estimates include:

- 1 in 102 (Martin's entry in 1949)

- 1 in 95 (Boodman's first entry in 1996)

- 1 in 92 (Freeman and Kendell's entry in 1976)

- 1 in 89 (Sagebiel's in 1961)

- 1 in 69 (Gralnick's in 1946)

- 1 in 63, among a group undergoing intensive ECT (Perry's in 1963–1979)

- 1 in 38 (Ehrenberg's in 1955)

- 1 in 30 (Kurland's in 1959)

- 1 in 9, among a group undergoing intensive ECT (Weil's in 1949)

- 1 in 4, among the very elderly, over 80 (Kroessler and Fogel's in 1974–1986).

Political abuse of psychiatry

Psychiatrists around the world have been involved in the suppression of individual rights by states in which the definitions of mental disease have been expanded to include political disobedience. Nowadays, in many countries, political prisoners are sometimes confined and abused in mental institutions. Psychiatry possesses a built-in capacity for abuse which is greater than in other areas of medicine. The diagnosis of mental disease can serve as proxy for the designation of social dissidents, allowing the state to hold persons against their will and to insist upon therapies that work in favor of ideological conformity and in the broader interests of society. In a monolithic state, psychiatry can be used to bypass standard legal procedures for establishing guilt or innocence and allow political incarceration without the ordinary odium attaching to such political trials.

Under the Nazi regime in the 1940s, the "duty to care" was violated on an enormous scale. In Germany alone 300,000 individuals that had been deemed mentally ill, work-shy or feeble-minded were sterilized. An additional 200,000 were euthanized. These practices continued in territories occupied by the Nazis further afield (mainly in eastern Europe), affecting thousands more. From the 1960s up to 1986, political abuse of psychiatry was reported to be systematic in the Soviet Union, and to surface on occasion in other Eastern European countries such as Romania, Hungary, Czechoslovakia, and Yugoslavia, as well as in Western European countries, such as Italy. An example of the use of psychiatry in the political field is the "case Sabattini", described by Giorgio Antonucci in his book Il pregiudizio psichiatrico. A "mental health genocide" reminiscent of the Nazi aberrations has been located in the history of South African oppression during the apartheid era. A continued misappropriation of the discipline was later attributed to the People's Republic of China.

K. Fulford, A. Smirnov, and E. Snow state: "An important vulnerability factor, therefore, for the abuse of psychiatry, is the subjective nature of the observations on which psychiatric diagnosis currently depends." In an article published in 1994 by the Journal of Medical Ethics, American psychiatrist Thomas Szasz stated that "the classification by slave owners and slave traders of certain individuals as Negroes was scientific, in the sense that whites were rarely classified as blacks. But that did not prevent the 'abuse' of such racial classification, because (what we call) its abuse was, in fact, its use." Szasz argued that the spectacle of the Western psychiatrists loudly condemning Soviet colleagues for their abuse of professional standards was largely an exercise in hypocrisy. Szasz states that K. Fulford, A. Smirnov, and E. Snow, who correctly emphasize the value-laden nature of psychiatric diagnoses and the subjective character of psychiatric classifications, fail to accept the role of psychiatric power. He stated that psychiatric abuse, such as people usually associated with practices in the former USSR, was connected not with the misuse of psychiatric diagnoses, but with the political power built into the social role of the psychiatrist in democratic and totalitarian societies alike. Musicologists, drama critics, art historians, and many other scholars also create their own subjective classifications; however, lacking state-legitimated power over persons, their classifications do not lead to anyone's being deprived of property, liberty, or life. For instance, a plastic surgeon's classification of beauty is subjective, but the plastic surgeon cannot treat his or her patient without the patient's consent, so there cannot be any political abuse of plastic surgery.

The bedrock of political medicine is coercion masquerading as medical treatment. In this process, physicians diagnose a disapproved condition as an "illness" and declare the intervention they impose on the victim a "treatment," and legislators and judges legitimate these categorizations. In the same way, physician-eugenicists advocated killing certain disabled or ill persons as a form of treatment for both society and patient long before the Nazis came to power.

From the commencement of his political career, Hitler put his struggle against "enemies of the state" in medical rhetoric. In 1934, addressing the Reichstag, he declared, "I gave the order… to burn out down to the raw flesh the ulcers of our internal well-poisoning." The entire German nation and its National Socialist politicians learned to think and speak in such terms. Werner Best, Reinhard Heydrich's deputy, stated that the task of the police was "to root out all symptoms of disease and germs of destruction that threatened the political health of the nation… [In addition to Jews,] most [of the germs] were weak, unpopular and marginalized groups, such as gypsies, homosexuals, beggars, 'antisocials', 'work-shy', and 'habitual criminals'."

In spite of all the evidence, people ignore or underappreciate the political implications of the pseudotherapeutic character of Nazism and of the use of medical metaphors in modern democracies. Dismissed as an "abuse of psychiatry", this practice is a controversial subject not because the story makes psychiatrists in Nazi Germany look bad, but because it highlights the dramatic similarities between pharmacratic controls in Germany under Nazism and those that have emerged in the US under the free market economy.

Therapeutic state

The "therapeutic state" is a phrase coined by Szasz in 1963. The collaboration between psychiatry and government leads to what Szasz calls the "therapeutic state", a system in which disapproved actions, thoughts, and emotions are repressed ("cured") through pseudomedical interventions. Thus suicide, unconventional religious beliefs, racial bigotry, unhappiness, anxiety, shyness, sexual promiscuity, shoplifting, gambling, overeating, smoking, and illegal drug use are all considered symptoms or illnesses that need to be cured. When faced with demands for measures to curtail smoking in public, binge-drinking, gambling or obesity, ministers say that "we must guard against charges of nanny statism". The "nanny state" has turned into the "therapeutic state" where nanny has given way to counselor. Nanny just told people what to do; counselors also tell them what to think and what to feel. The "nanny state" was punitive, austere, and authoritarian, the therapeutic state is touchy-feely, supportive—and even more authoritarian. According to Szasz, "the therapeutic state swallows up everything human on the seemingly rational ground that nothing falls outside the province of health and medicine, just as the theological state had swallowed up everything human on the perfectly rational ground that nothing falls outside the province of God and religion".

Faced with the problem of "madness", Western individualism proved to be ill-prepared to defend the rights of the individual: modern man has no more right to be a madman than medieval man had a right to be a heretic because if once people agree that they have identified the one true God, or Good, it brings about that they have to guard members and nonmembers of the group from the temptation to worship false gods or goods. A secularization of God and the medicalization of good resulted in the post-Enlightenment version of this view: once people agree that they have identified the one true reason, it brings about that they have to guard against the temptation to worship unreason—that is, madness.

Civil libertarians warn that the marriage of the State with psychiatry could have catastrophic consequences for civilization. In the same vein as the separation of church and state, Szasz believes that a solid wall must exist between psychiatry and the State.

"Total institution"

In his book Asylums, Erving Goffman coined the term 'total institution' for mental hospitals and similar places which took over and confined a person's whole life. Goffman placed psychiatric hospitals in the same category as concentration camps, prisons, military organizations, orphanages, and monasteries. In Asylums Goffman describes how the institutionalization process socializes people into the role of a good patient, someone 'dull, harmless and inconspicuous'; it in turn reinforces notions of chronicity in severe mental illness.

Law

In the US, critics of psychiatry contend that the intersection of the law and psychiatry create extra-legal entities. For example, the insanity defense, leading to detainment in a psychiatric institution versus a prison, can be worse than criminal imprisonment according to some critics, as it involves the risk of compulsory medication with neuroleptics or the use of electroshock treatment. While a criminal imprisonment has a predetermined and known time of duration, patients are typically committed to psychiatric hospitals for indefinite durations, an arguably outrageous imposition of fundamental uncertainty. It has been argued that such uncertainty risks aggravating mental instability, and that it substantially encourages a lapse into hopelessness and acceptance that precludes recovery.

Involuntary hospitalization

Critics see the use of legally sanctioned force in involuntary commitment as a violation of the fundamental principles of free or open societies. The political philosopher John Stuart Mill and others have argued that society has no right to use coercion to subdue an individual as long as they do not harm others. Research evidence regarding violent behavior by people with mental illness does not support a direct connection in most studies. The growing practice, in the United Kingdom and elsewhere, of Care in the Community was instituted partly in response to such concerns. Alternatives to involuntary hospitalization include the development of non-medical crisis care in the community.

The American Soteria project was developed by psychiatrist Loren Mosher as an alternative model of care in a residential setting to support those experiencing psychiatric symptoms or extreme states. The Soteria houses closed in 1983 in the United States due to lack of financial support. Similar programs were established in Europe, including in Sweden and other North European countries. In 2015, a Soteria House opened in Vermont, US.

The physician Giorgio Antonucci, during his activity as a director of the Ospedale Psichiatrico Osservanza of Imola in Italy from 1979 to 1996, refused any form of coercion and any violation of the fundamental principles of freedom, questioning the basis of psychiatry itself.

Psychiatry as pseudoscience and failed enterprise

Many of the above issues lead to the claim that psychiatry is a pseudoscience. According to some philosophers of science, for a theory to qualify as science it needs to exhibit the following characteristics:

- parsimony, as straightforward as the phenomena to be explained allow (see Occam's razor);

- empirically testable and falsifiable (see Falsifiability);

- changeable, i.e. if necessary, changes may be made to the theory as new data are discovered;

- progressive, encompasses previous successful descriptions and explains and adds more;

- provisional, i.e. tentative; the theory does not attempt to assert that it is a final description or explanation.

Psychiatrists Colin A. Ross and Alvin Pam maintain that biopsychiatry does not qualify as a science on many counts.

Psychiatric researchers have been criticized on the basis of the replication crisis and textbook errors. Questionable research practices are known to bias key sources of evidence.

Stuart A. Kirk has argued that psychiatry is a failed enterprise, as mental illness has grown, not shrunk, with about 20% of American adults diagnosable as mentally ill in 2013.

According to a 2014 meta-analysis, psychiatric treatment is no less effective for psychiatric illnesses in terms of treatment effects than treatments by practitioners of other medical specialties for physical health conditions. The analysis found that the effect sizes for psychiatric interventions are, on average, on par with other fields of medicine.

Diverse paths

Szasz has since (2008) re-emphasized his disdain for the term anti-psychiatry, arguing that its legacy has simply been a "catchall term used to delegitimize and dismiss critics of psychiatric fraud and force by labeling them antipsychiatrists". He points out that the term originated in a meeting of four psychiatrists (Cooper, Laing, Berke and Redler) who never defined it yet "counter-label[ed] their discipline as anti-psychiatry", and that he considers Laing most responsible for popularizing it despite also personally distancing himself. Szasz describes the deceased (1989) Laing in vitriolic terms, accusing him of being irresponsible and equivocal on psychiatric diagnosis and use of force, and detailing his past "public behavior" as "a fit subject for moral judgment" which he gives as "a bad person and a fraud as a professional".

Daniel Burston, however, has argued that overall the published works of Szasz and Laing demonstrate far more points of convergence and intellectual kinship than Szasz admits, despite the divergence on a number of issues related to Szasz being a libertarian and Laing an existentialist; that Szasz employs a good deal of exaggeration and distortion in his criticism of Laing's personal character, and unfairly uses Laing's personal failings and family woes to discredit his work and ideas; and that Szasz's "clear-cut, crystalline ethical principles are designed to spare us the agonizing and often inconclusive reflections that many clinicians face frequently in the course of their work". Szasz has indicated that his own views came from libertarian politics held since his teens, rather than through experience in psychiatry; that in his "rare" contacts with involuntary mental patients in the past he either sought to discharge them (if they were not charged with a crime) or "assisted the prosecution in securing [their] conviction" (if they were charged with a crime and appeared to be prima facie guilty); that he is not opposed to consensual psychiatry and "does not interfere with the practice of the conventional psychiatrist", and that he provided "listening-and-talking ("psychotherapy")" for voluntary fee-paying clients from 1948 until 1996, a practice he characterizes as non-medical and not associated with his being a psychoanalytically trained psychiatrist.

The gay rights or gay liberation movement is often thought to have been part of anti-psychiatry in its efforts to challenge oppression and stigma and, specifically, to get homosexuality removed from the American Psychiatric Association's (APA) Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. However, a psychiatric member of APA's Gay, Lesbian, and Bisexual Issues Committee has recently sought to distance the two, arguing that they were separate in the early '70s protests at APA conventions and that APA's decision to remove homosexuality was scientific and happened to coincide with the political pressure. Reviewers have responded, however, that the founders and movements were closely aligned; that they shared core texts, proponents and slogans; and that others have stated that, for example, the gay liberation critique was "made possible by (and indeed often explicitly grounded in) traditions of antipsychiatry".

In the clinical setting, the two strands of anti-psychiatry—criticism of psychiatric knowledge and reform of its practices—were never entirely distinct. In addition, in a sense, anti-psychiatry was not so much a demand for the end of psychiatry, as it was an often self-directed demand for psychiatrists and allied professionals to question their own judgments, assumptions and practices. In some cases, the suspicion of non-psychiatric medical professionals towards the validity of psychiatry was described as anti-psychiatry, as well the criticism of "hard-headed" psychiatrists towards "soft-headed" psychiatrists. Most leading figures of anti-psychiatry were themselves psychiatrists, and equivocated over whether they were really "against psychiatry", or parts thereof. Outside the field of psychiatry, however—e.g. for activists and non-medical mental health professionals such as social workers and psychologists—'anti-psychiatry' tended to mean something more radical. The ambiguous term "anti-psychiatry" came to be associated with these more radical trends, but there was debate over whether it was a new phenomenon, whom it best described, and whether it constituted a genuinely singular movement. In order to avoid any ambiguity intrinsic to the term anti-psychiatry, a current of thought that can be defined as critique of the basis of psychiatry, radical and unambiguous, aims for the complete elimination of psychiatry. The main representative of the critique of the basis of psychiatry is an Italian physician, Giorgio Antonucci, the founder of the non-psychiatric approach to psychological suffering, who posited that the "essence of psychiatry lies in an ideology of discrimination".

In the 1990s, a tendency was noted among psychiatrists to characterize and to regard the anti-psychiatric movement as part of the past, and to view its ideological history as flirtation with the polemics of radical politics at the expense of scientific thought and enquiry. It was also argued, however, that the movement contributed towards generating demand for grassroots involvement in guidelines and advocacy groups, and to the shift from large mental institutions to community services. Additionally, community centers have tended in practice to distance themselves from the psychiatric/medical model and have continued to see themselves as representing a culture of resistance or opposition to psychiatry's authority. Overall, while antipsychiatry as a movement may have become an anachronism by this period and was no longer led by eminent psychiatrists, it has been argued that it became incorporated into the mainstream practice of mental health disciplines. On the other hand, mainstream psychiatry became more biomedical, increasing the gap between professionals.

Henry Nasrallah claims that while he believes anti-psychiatry consists of many historical exaggerations based on events and primitive conditions from a century ago, "antipsychiatry helps keep us honest and rigorous about what we do, motivating us to relentlessly seek better diagnostic models and treatment paradigms. Psychiatry is far more scientific today than it was a century ago, but misperceptions about psychiatry continue to be driven by abuses of the past. The best antidote for antipsychiatry allegations is a combination of personal integrity, scientific progress, and sound evidence-based clinical care".

A criticism was made in the 1990s that three decades of anti-psychiatry had produced a large literature critical of psychiatry, but little discussion of the deteriorating situation of the mentally troubled in American society. Anti-psychiatry crusades have thus been charged with failing to put suffering individuals first, and therefore being similarly guilty of what they blame psychiatrists for. The rise of anti-psychiatry in Italy was described by one observer as simply "a transfer of psychiatric control from those with medical knowledge to those who possessed socio-political power".

Critics of this view, however, from an anti-psychiatry perspective, are quick to point to the industrial aspects of psychiatric treatment itself as a primary causal factor in this situation that is described as "deteriorating". The numbers of people labeled "mentally ill", and in treatment, together with the severity of their conditions, have been going up primarily due to the direct efforts of the mental health movement, and mental health professionals, including psychiatrists, and not their detractors. Envisioning "mental health treatment" as violence prevention has been a big part of the problem, especially as you are dealing with a population that is not significantly more violent than any other group.

On October 7, 2016, the Ontario Institute for Studies in Education (OISE) at the University of Toronto announced that they had established a scholarship for students doing theses in the area of antipsychiatry. Called "The Bonnie Burstow Scholarship in Antipsychiatry", it is to be awarded annually to an OISE thesis student. An unprecedented step, the scholarship should further the cause of freedom of thought and the exchange of ideas in academia. The scholarship is named in honor of Bonnie Burstow, a faculty member at the University of Toronto, a radical feminist, and an antipsychiatry activist. She is also the author of Psychiatry and the Business of Madness (2015).

Some components of antipsychiatric theory have in recent decades been reformulated into a critique of "corporate psychiatry", heavily influenced by the pharmaceutical industry. A recent editorial about this was published in the British Journal of Psychiatry by Moncrieff, arguing that modern psychiatry has become a handmaiden to conservative political commitments. David Healy is a psychiatrist and professor in psychological medicine at Cardiff University School of Medicine, Wales. He has a special interest in the influence of the pharmaceutical industry on medicine and academia.

In the meantime, members of the psychiatric consumer/survivor movement continued to campaign for reform, empowerment and alternatives, with an increasingly diverse representation of views. Groups often have been opposed and undermined, especially when they proclaim to be, or when they are labeled as being, "anti-psychiatry". However, as of the 1990s, more than 60 percent of ex-patient groups reportedly support anti-psychiatry beliefs and consider themselves to be "psychiatric survivors". Although anti-psychiatry is often attributed to a few famous figures in psychiatry or academia, it has been pointed out that consumer/survivor/ex-patient individuals and groups preceded it, drove it and carried on through it.

Criticism

A schism exists among those critical of conventional psychiatry between radical abolitionists and more moderate reformists. Laing, Cooper and others associated with the initial anti-psychiatry movement stopped short of actually advocating for the abolition of coercive psychiatry. Thomas Szasz, from near the beginning of his career, crusaded for the abolition of forced psychiatry. Today, believing that coercive psychiatry marginalizes and oppresses people with its harmful, controlling, and abusive practices, many who identify as anti-psychiatry activists are proponents of the complete abolition of non-consensual and coercive psychiatry.

Critics of antipsychiatry from within psychiatry itself object to the underlying principle that psychiatry is by definition harmful. Most psychiatrists accept that issues exist that need addressing, but that the abolition of psychiatry is harmful. Nimesh Desai concludes: "To be a believer and a practitioner of multidisciplinary mental health, it is not necessary to reject the medical model as one of the basics of psychiatry." and admits "Some of the challenges and dangers to psychiatry are not so much from the avowed antipsychiatrists, but from the misplaced and misguided individuals and groups in related fields."