By David J Strumfels on http://AMedelyofPotpourri.Blogspot.com/

(Wikipedia, 2/28/14): "Between 1751 and

1994 surface ocean pH is estimated to have decreased from

approximately 8.25 to 8.14 (how measured in 1751?),[5] representing

an increase of almost 30% in H+ ion concentration in the

world's oceans.[6][7] Available Earth System Models project that

within the last decade ocean pH exceeded historical analogs [8] and

in combination with other ocean biogeochemical changes could

undermine the functioning of marine ecosystems and many ocean goods

and services.[9]"

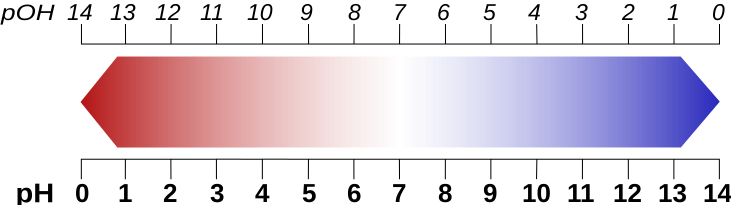

8.25 to 8.14 -- what does that mean? What it

does not mean is that the oceans are acidic, for their pH would have

to be below 7.0 to say that. In fact, we would call it alkaline

(the opposite of acidity). But acidification indicates a

direction, not a specific place on the pH scale (some climate

warming skeptics seem not to understand the difference) .

Chemically, pH is defined as the "negative log (hydrogen

ion concentration)". But what does THAT mean?

The hydrogen ion, or H+ (a hydrogen

atom without its electron, or a bare proton), is the main acidic

species in water. If the concentration of H+ is

8.00E-8 = 0.00000001 Molar (moles per liter, or just M), then the log

of that number is -8.00, its negative log is 8.00, and so the pH is

8.00. As to the specific cases here: pH 8.25 =>

-8.25; antilog (-8.25), or 10 to the power of the number)

yields 5.62E-9 H+ M, while 8.16 => -8.16 =>

7.14E-9 H+ M. That's a difference of 1.52E-9 H+

M concentration, or 0.00000000152M. Yes, it is a 29% increase

in acidity, mathematically. Of course, 29% of practically

nothing is even closer to actually nothing. But

chemically, especially biochemically, it can be very important.

For example, your blood pH has to be kept within a

narrow range of 8.25 and 8.35, or illness, even death, can

result. I do not know all the reasons for this, but I can tell

you that many biomolecules have both basic (opposite of acidic) and

acidic forms, and they are chemically different. They may have

to be kept within a very narrow equilibrium of basic and acidic

forms, each running a different reaction. Or some are all

necessarily basic at this pH, while others all acidic. At pHs

near 7.0 (neutrality), these equilibria are extremely

sensitive to these tiny changes I outlined above.

So it is not difficult to see how a drop in 0.09

pH units (combined with a degree or two warming) could wreak havoc on

numerous sea organisms, plant, animal, protozoan, or bacterial. On

the other hand, the immensity of the oceans assures that there will be

pH (and temperature) variations, in time and location, so sea life

should be expected to be a little more hardy. But there are still

fairly strict limits. The 21'st century will surely test those

limits.

A little more chemistry now. We blithely speak of

CO2 increasing water acidity, but how?

First, CO2 is mildly soluble in

water, the lower the water temperature, or the higher the water

pressure, the more soluble (for thermodynamic reasons we need go into

here) it is. That isn't enough for acidity, however. There has to

be a chemical reaction between CO2 and

H2O

first: CO2 +

H2O

<=> HCO3-

and H+.

The <=> sign means the reaction goes in both directions; which

set of reactants/products is favored depends on

various conditions. Cold leans toward the first

two, pressure the opposite way. This again is thermodynamics, with

enthalpy and entropy competing against each other. At the low

concentrations of CO2,

in general the latter is favored. But it's still a tiny contribution

of H+, enough, as

you've seen, to lower ocean water an average of 0.1 pH units over the

last two hundred years (and I would not be surprised if 0.5 – 0.7

units of that is within the last 30-40 years, and

it ~doubles by 2100 – this is serious).