May 8, 2006 by Michael Buerger

Original link: http://www.kurzweilai.net/from-the-enlightenment-to-n-lightenment

The criminal potentials inherent in molecular manufacturing include powerful new illegal drugs, mass murder via compromised assembly codes, and a “killer virus” crossing out of cyberspace into the physical realm. A criminal-justice futurist examines the possibilities.

Original link: http://www.kurzweilai.net/from-the-enlightenment-to-n-lightenment

The criminal potentials inherent in molecular manufacturing include powerful new illegal drugs, mass murder via compromised assembly codes, and a “killer virus” crossing out of cyberspace into the physical realm. A criminal-justice futurist examines the possibilities.

On top of my physical desk sits a copy of Pandaemonium: The Coming of the Machine as Seen by Contemporary Observers, 1660-1886, Humphrey Jennings’ “imaginative history of the Industrial Revolution.” On my computer desktop are essays by the authors of this volume (and the previous one1), the possible precursors of Pan-nano-daemonium: The Coming of the Micro-Machine.

In one of those essays, “The Need for Limits,” Chris Phoenix speaks of the Enlightenment in terms of a synergy: enhanced human productivity with machines, partially supporting a philosophical examination of the human condition. Though certainly that, the Enlightenment also was a watershed period when the economic foundations of the European economy changed, and the authority of Revealed Truth was forced to contend with the authority of Rational Thought and its practical cousin, Scientific Inquiry. The shifts in the economy created a massive transformation of social life, from agrarian to urban. The current era has parallels to all of these forces, movements already in play but not yet complete…and in some cases not fully articulated.

As a peripheral member of a futurists group2 in my professional field (policing, and more broadly, criminal justice), I have noticed that futurists tend to be concerned with the end results of trends, the state of things ten, twenty, or fifty years from now. By contrast, I am more concerned with the collateral damage we may sustain in the process of getting to those future states from where we are now.

This essay approaches that interstitial state in four sections. The first section looks at the control of the technology; the second, for the criminal potentials inherent in it. Using the template of the Enlightenment, the third section looks at the darker channels of social transformation, particularly the impact on work and social worth. The fourth section draws an admittedly leap-of-faith parallel between the Enlightenment’s impact on religious authority, and technology’s impact upon the authority of economic capital and law.

Nanotechnology holds remarkable potential to change the world, but like most recent technologies, it emerges within a larger system of laws, codes of conduct, and social expectations developed for previous capacities. Those mechanisms will shape its emerging uses, possibly retarding or constraining the applications of the technology in undesirable ways. At issue is whether micro-level processing will be merely one more tool (and thus alter our lives incrementally), or a Promethean breakthrough that will alter human existence in profound ways. My interest, as one who stands outside the Halls of Science looking in, tends to center on the possibilities that I can understand from a layman’s perspective.

Trying to grasp in layman’s terms the implications of a new and only marginally understood technology leads to a search for analogies, framing the new in terms of the familiar (for good or ill).

Control

As a non-scientist, the most salient question for me is, “When do I get to play with the new toy?” Given the general limits of corporate use of nanotechnology, the first new toy that will become available to me most likely will be the desktop assembler, or personal nanofactory (PN).The most knowledgeable members of CRN’s Global Task Force3 have engaged in a lengthy discussion about desktop manufacturing and its social consequences, and as of this writing, there seems to be a lack of consensus about the capacity, and thus the full impact, of PNs. If we accept the position of the optimists, and expect fully-capable devices to be available in the not-too-distant future, secondary questions arise: Will the devices be provided in fully-capable form (probably transformative), or will their functionality be curtailed in defense of the corporate profits to be derived from them? If the latter, how will control be maintained? Some answers are perhaps to be found in current trends, since the courts often look to historical analogs in dealing with new issues.

If we posit that desktop manufacturing becomes widely available, as seems inevitable, the dominant forces of the economy have two avenues of recourse to maintain control over the new technology for monetary benefit. The first will be the control of raw materials for molecular assembly, which appears to share the delivery profile of heating fuels in contemporary life. More important is the second area, already suggested by Phoenix: patents and copyrights.4

The development of nanotechnology is taking place within a corporate nest of ideas and resources (much like licensed computer software development), with some independent researchers and consortia operating on a freeware basis. Molecular assembly at any sort of commercial or individual level will require patterns to guide assembly, and these are likely to be controlled by patents. The majority of patents are almost certain to be controlled by corporate interests. Renewable user site licenses, comparable to commercial software packages, are the most likely form of retaining economic benefit for a corporate entity. One of the possible ways of maintaining economic control over site licenses would be some form of cyber-degradable program that self-destructs after a finite period, and must be renewed. For example, a user could download (or purchase on a one-use or renewable-use media platform) the code that would allow the manufacture of only a certain number of rolls of toilet paper by a personal nanofactory.

Patents and the fundamental premises of intellectual property are already under challenge, but the challenges have been met with an equally strong legal response anchored in precedent. The courts have handed the reins of control over digital recordings of music to the star-making machinery behind the popular songs through conservative interpretation of intellectual property statutes. The huge profits to be made from licensing technological advancements for industry virtually assures that the field of nanotechnology will be similarly bound.

The most recent Promethean technology, file-sharing, theoretically stood to liberate music from the chains of capital. However, Napster, Kaaza, Grokster, and their lesser clones have lost the legal battles, and the technology has been co-opted by industry giants into new distribution-for-profit mechanisms. Corporations and universities alike write eminent domain over patents and patentable discoveries into their employment contracts, and genetic patterns and discoveries are subject to copyright. Unknown garage bands and the metaphorical garage workshops of independent researchers still can be found beyond the current reach of over-grasping capital, but only until they become good or useful enough to attract attention.

As new genetic “building block” discoveries and other chemical compounds are placed under patent, the copyright has become the new castle moat or the new dog in the manger (depending upon one’s perspective), intended to keep easily-duplicated “properties” under the control of their owners. Paradoxically, only those products deemed legitimate are defended by patents and lawsuits so vigorously; illegal products and contraband are not. Corporate interests have far deeper pockets and a true metric for measuring loss and injury. There is greater freedom in the illicit trades, where control of trafficked, harmful artifacts rests with hugely inefficient, underfunded, and understaffed public enforcement agencies.

The exponential explosion of child pornography (and its hate- and racial supremacy-based counterparts) over the Internet is a cautionary tale in its own right. Like the illicit drug trade in the physical world, neither child porn nor hate-mongering is impervious to law enforcement efforts, but the occasional victories of enforcement seem to have little long-term effect on the larger industry or movement. The underground distribution of molecular patterns for assembly might easily be accomplished by the same mechanisms, like the basic virus codes that any script-kiddie can download, tinker with, and release back into the wild.

While the first generation of personal nanofactories probably will come with a fixed number of pre-programmed patterns, market forces will demand versatility. Units will need a capacity to acquire new assembly patterns as they are developed, and there seem to be few options beyond what is now available for computer data. Patterns may be downloaded over hardwired or Wi-Fi networks, or be manually transferred by whatever media replace the current disk drives and flash memory sticks. Each format would spawn a black market of unknown proportions, and with the black markets come the accompanying risks of epidemic and pandemic consequences of criminal use.

Criminal Potentials

We should anticipate that a new drug industry will piggyback on the basic molecular assembly phenomenon, and the potential implications for the social fabric are enormous. One of the most desirable benefits of nanotechnology is that of precise targeting of therapeutic drugs; however, the same technology will have associated benefits for illegal pharmacopoeia. While the complexity of the patterns most likely will delay this until a second or third-level level of PN development, once the basic patterns for psychotropic drugs are understood and the assembly technology sufficiently enabled, individual drug manufacture is almost certain to become a social tsunami. There are strong analogies to the current methamphetamine epidemic: less than two decades ago, the manufacture of crystal methamphetamine required a well-equipped clandestine lab, a chemist, a criminal organization for protection and distribution. Today, meth is the new bathtub gin, easily made in any number of Rube Goldberg processes in basements, trailers, campers, garages, or pickup trucks.Unlike methamphetamine, a micro-assembly drug manufacture process would need only the basic molecular components, not the more elaborate precursor chemicals (like pseudoephedrine) whose control is now part of our anti-drug strategy. That suggests a much greater availability, with corollary hazards of greater social experimentation and conceivably even poly-drug experimentation. The toxic byproducts of meth labs are threats to law enforcement agencies, the families of meth addicts, and neighborhoods. We do not yet know the degree to which micro-manufacture byproducts will be toxic, if at all.

Illicit micro-manufacture may be a mixed blessing. On the one hand, effectively eliminating organized crime from the market may lessen the toxic effects of the war on drugs: the corruption involved with importation of drugs, and the violence of competing drug markets. At least potentially, even the criminogenic nature of drug dependency may be lessened: since the base materials would likely be the same as for legitimate micro-manufacture, it is less likely that a specialized, higher-priced supply chain would be necessary. The dynamics of that supply chain create additional crimes: violence among criminal enterprises competing for turf high, and both personal and property crime committed by addicts desperate to meet the dealer’s price. Absent the supply market, the cost of personally manufactured drugs would be cheaper, and the risks of their creation considerably lower in terms of legal discovery and interdiction. However, the potential free access to addictive and mind-altering substances will almost certainly exacerbate the social problems associated with the addictions and dependencies that result. The same delivery method could surreptitiously create markets for new designer drugs, addictive and involuntarily piggybacked on legitimately disseminated nanoproduct codes. The number of “what ifs” that need to be resolved before either scenario happens leave the possibilities within the realm of fiction for now, but if the analogies to the Internet hold true, they must be anticipated as a contingency.

Should we ever develop a drug-based cure for the addictions, of course, it might be to our collective advantage to attempt to disseminate it via whatever outlaw networks and mechanisms develop, the angelic counterpart to the demonic assault-by-micro-drugs of the original scenario. Therapeutic nano-rehab, even at the time of a medical crisis, may not be sufficient to stem the drug crisis, however. Involuntary detoxification has a poor history of neutralizing the psychological dependencies that drive post-sobriety returns to addictive substances. The “evil twin” of involuntary detoxification is involuntary addiction.

Lurking beyond therapeutic use is the possibility of totalitarian control using the same methods. The Promethean paradox that attends all new technologies is even more pronounced for those that escape Newtonian-level detection. Medical research is racing ahead in its understanding of neural processes, including the sites in the brain responsible for certain behaviors. As nanomedicine develops capacities for intervening in psychological dependencies or other maladies, it also develops the capacity for inducing mind control or other forms of incapacitation.

Downstream, there is also the potential for mass murder via compromised assembly codes. In the physical world, tainting a medicine with poison can only be done efficiently at the factory source, and even then must bypass or defeat stringent quality control measures. Any other corruption can take place only on a relatively small scale. The introduction of a virulent and unsuspected corruption of a drug assembly code is not so limited. It shares more in common with the computer virus than the Tylenol poisoner. Since black market codes originate and enter the data stream outside the domain of legitimate quality control measures, and the drug-using community is unlikely to give designer drug codes great scrutiny (at least in the initial rounds), “massassination” (mass assassination or “pharmaceutical cleansing”) via bogus codes is a distinct possibility in a networked distribution system. It would challenge both medical institutions and law enforcement agents. It is admittedly an outside possibility, requiring a rare combination of technological savvy and social alienation, but the world since September 2001 has been dealing with more and more “one in a bazillion” scenarios. Nothing should be taken off the table in terms of exploring, and preparing for, unpleasant misappropriation of technology.

To a certain degree, the massassination scenario depends upon the nature of the dissemination of manufacture codes. The most logical assumption is that distribution of product blueprints for desktop manufacturing will be done via the Internet or its successor entity. The current attempts to defeat music and film pirate copies would have serious analogs in any new process that challenged traditional sources of corporate and investment income, especially unrestricted use of molecular assembly technology. The Spy vs. Spy battle between corporate interests and hacktivism will doubtless continue in the nano- and micro-arenas as in cyberspace. Even if controls evolve another way, such as physical distribution of codes on one-use portable media like the flash memory stick, markets for stolen and counterfeit products will emerge, just as the current computer viruses and malware are piggybacked on the legitimate use of the Internet. Beating security encryptions to transform a one-use code into a version capable of electronic dissemination will be an instant challenge for the criminal and black-hat hacking communities.

There are some differences, though. While the viruses and Trojan horses that hector cyberspace have consequences ranging from irritating (the Blue Screen of Death) to life-changing (severe financial crises resulting from identity theft), it is only at the most extreme range that they could be considered life-threatening. Identity theft that labels an innocent citizen as a dangerous criminal has some potential for creating life-threatening situations, but most of the jeopardy is financial or social. Viruses and worms may take down a network or three, or transform the World Wide Web into the World Wide Wait with deleterious consequences for commerce, but they do not directly assault the networks’ users. A corrupted, mislabeled, or maliciously designed micro-manufacture code could “break the fourth wall,” crossing out of cyberspace into the physical realm.

The closest parallel in the physical world, the batch of bad heroin that kills users in clusters, does not really provide an accurate analog for a malicious assembly code incident. Relatively few seek heroin under any circumstances, and no one but the most desperate heroin addict would seek out bad heroin (as has happened in some isolated cases). The first “killer virus” loose in whatever network provides product codes for PNs will affect hundreds and perhaps thousands of innocents, whether it comes as a terrorist strike or an unintended consequence of a hacking adventure. No one will have to seek it: once in the wild, it will arrive unbidden in the In Box.

Defenses to such a scenario potentially exist, but security measures are one of the most attractive fruits of the Tree of Knowledge. Like contemporary Internet defenses, and the laws passed to outlaw new designer drugs, defensive maneuvers almost always stimulate new offensive attacks. Any combination of zeros and ones, in any transportation medium, can be hijacked and compromised: the track record of Internet security does not bode well for the free and easy commercial transfer of assembly codes for the molecules-up creation of products.

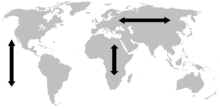

Social

During the Industrial Revolution in England, improved agricultural efficiencies accelerated the process of enclosure, dislocating the rural population no longer needed for raising and harvesting crops. Simultaneous improvements in the production of iron and steel, in weaving, and other areas began to transform cottage industries into factory-based industries, and urbanization rapidly changed the face of the country. The nature of trade shifted from one-off mercantile ventures and royal charters to stable capital for long-term ventures. Factory industries supplanted cottage industries, local artisans, and craft guilds, but the concentration of work in brick-and-mortar containers still left some out of work: the notorious “surplus labor” that kept wages low. The expansion of the new manufacturing base managed to absorb surplus labor for some time, until the advent of widespread robotics in the second half of the twentieth century.A robust generation of personal nanofactories may very well bifurcate commerce into those items that can be manufactured at home and those which still must be purchased through the familiar retail supply chains. While a certain amount of jobs will be created around the transportation of raw materials for PNs, they will be paltry in comparison to the jobs the devices displace in manufacture, transport, and sales. Globalization has already imposed a certain amount of social dislocation in the manufacturing sectors; a maturing nanotechnology could very well trigger a long-term social dislocation not seen since the English migration from the newly-enclosed farmlands to the new factories of the Industrial Revolution.

The need for human labor seems to be diminishing at an accelerated rate inverse to Ray Kurzweil’s description5 of the advance of technology. The shift from human muscle to animal muscle took millennia; from animal to human-guided mechanical, centuries; from human-guided to robotic, decades; and the emergence of computer-directed manufacture seems measured in years if not months. Human society, however, still is anchored in a near-medieval paradigm where social worth is measured by the type and extent of work one engages in. The pecking order of work starts at the menial and dirty level, maids and animal rendering and manual labor (the province of illegal immigrants and paroled convicts) comparable to carrying the hod. The next step up is the marginally cleaner and less taxing “service economy” of McJobs, which jousts with the decline of blue-collar union-affiliated manufacturing jobs for the next higher rung (salaries and benefits alone give the advantage to unionized jobs, regardless of the decades-long decline in union membership, though the recent perturbations in the airline and automobile industries in particular, and corporate pension plans generally, leave even that in doubt). Above that are the traditional white-collar jobs, but the new aristocracy—sharply defined by the accelerating concentration of wealth in at least American society—is comprised of those who “let their money work for them,” the investing class, the owners of the means of production.

Work is devalued in other ways: in the symbolic change of language in which employees are now called “associates,” with a presumed stake in the corporate success that is not mirrored anywhere in the reward system; in the stock market rewarding corporate actions that trim the workforce; and in the precipitous erosion of industry-sponsored pensions. Human labor has been, or is in the process of being, effectively decoupled from the part of the economy that is valued. The long-term consequences of this are by no means clear, but the advent of a personal –nanofactories will not necessarily create a widespread leisure class.

Another of the volumes on my physical desktop is William Julius Wilson’s When Work Disappears: The World of the New Urban Poor. It deals with the “left behind” problem of those under a double burden of low social status and of being dependent upon jobs in industries that have moved elsewhere (to Alabama, to Mexico, or to China). While the analogy to a nanotechnology shift need not be exact, Wilson’s depictions and analyses offer a powerful warning we may need to confront within a generation: what are the social consequences when there are no alternative employment outlets for surplus labor? American history of the 20th century holds small hope that our social attitudes will change rapidly: the unemployed, underemployed, and “idle” always have been despised for not somehow rising above the crushing weight of social and economic forces beyond their control. Revolution traditionally has been pointless or counterproductive, and Cite Soliel endures in its multiple forms around the globe despite the potential and promises of globalization, the Green Revolution, and countless other advances.

It is tempting to suggest that nano-communes, with internal self-sufficiency that leaven the worst effects of industrial-era unemployment, will free the human spirit for more cerebral endeavors. Futures are almost never equally distributed when they arrive, and Utopian dreams of that kind have a history of being measured in months rather than decades or eras. It is difficult to envision the rise of a labor movement comparable to those of nineteenth-century Britain and the United States; it is almost easier to predict the widespread distribution of limited-capacity PNs as a form of social welfare (and social placation of the underclass).

Larger questions arise out of this potential for increased social marginality. The income gap between rich and poor has been widening for more than two decades. Globalization has transformed the American economy, and the household economy has suffered as a result. The degree to which nanotechnology, the Internet, and other technologies accelerate or buffer the social decoupling of work and status is still an undiscovered country. If the cumulative effect is acceleration, we need to anticipate the range of human adaptations that will follow. If one no longer is attached in any meaningful way to an economy and the political ideology that supports it, how long can that authority hold one’s allegiance? And what are the alternatives if the allegiance cannot otherwise be reinforced?

Authority

Although it is a commonplace to think of religious worship as timeless, it actually undergoes periodic major shifts, often triggered by secular events. In the first century of the Common Era, the nature of revelation itself was transformed from the direct presence of a transcendent deity to the interpretation of a written Scripture. For Jews, the destruction of the Holy of Holies in the Second Temple ended the traditional direct contact of the High Priests. For Christians, the sudden absence of their Messiah from the streets of Jerusalem transformed the Judaic concept of messianic return into an entirely new understanding the relationship between human beings and their Creator.The struggle for primacy between the Catholic Church and secular governments began soon after Christianity was adopted as the official religion of the Roman Empire. It continued through the Investiture Controversy of the Middle Ages, and was the decisive factor in the success of the Reformation. However, the waning of the dominance of religion was a process begun centuries earlier by resistance (“heresy”) within the Church itself, beginning with the Great Schism of the Eastern Orthodox traditions. The purification movements that created monastic orders within the Church presaged the later coming of the Reformation, which relocated purifying reform outside the Church and ended the sole authority of Rome to arbitrate Christian salvation. The secular challenges arising from the Enlightenment remain at play in the contemporary questions of Church and State, Science and Belief, and authority to define human relations. Increasing secularity jousts with the rise of fundamentalism and of sects, undermining traditional “mainstream” churches.

Whether the maturing of nanotechnology will impact the continuing struggle of religious authority is unclear. The potential is there, certainly, as the manipulation of matter at the molecular level comes perilously close to “playing God,” especially where it might affect what it means to be human. Artificial intelligence, genetic engineering, and cybernetic enhancements pose imminent challenges to the religious understandings of “human,” and nanotechnology bids to play a major role within each of those technologies. Public discourse in areas where the definitions of “life” are most contended are fueled as much by symbolism and metaphor as by science; misapprehensions and misunderstandings about nanotechnology may well be fuel for new battlefronts in what has been dubbed “the culture wars.”

During the Reformation, the monolithic authority of the Church of Rome was transformed into a limited number of Protestant denominations. The existence of each one allowed anyone to resist the Authority of the Catholic Church, and beyond that, the authority of any other church. (The earliest attempt to incorporate a denial of secular authority, under the banner of “No Bishops, No Barons,” was ruthlessly suppressed by secular forces, whose worldly enforcement had more immediate clout than the afterlife of religion.) The transformation of monolithic Authority into micro-authority created a market for allegiances. The old concept of rules defined and enforced by a monopolistic Church—enforced by excommunication, the denial of sacraments, and the resulting condemnation to an infernal afterlife—gave way to a free market of ideas and selection of, rather than submission to, authority that continues to this day. Catholic priests who wish to marry may find refuge in the Anglican communion. Protestant churches may fracture over rules of control and worship, and denominations may enter schism over ecclesiastical matters, as witness the current strain in the Anglican communion over the issue of gay bishops and clergy, and the social acceptance of homosexuality. Other issues less anchored in scriptural interpretation, like finances, may also trigger the sundering of ways for a congregation.

Using this as an analogy for secular considerations, it is an interesting exercise in speculation to consider whether nanotechnology generally, and desktop manufacturing in particular, will lead to nano-communes that eventually decouple individuals from the larger economy and the political system so closely tied to it. Such communities would be the natural descendants of the self-sufficient medieval monastic orders, the utopian communities of the mid-1800s, and the communes of the 1960s and beyond. Unlike their predecessors, they could be “off the grid” in important ways, but not necessarily withdrawn from the larger society.

In other realms, there is some additional promise in the potential for using nanotechnology as a recycling outlet. Molecular disassembly as a precursor to molecular assembly may be a completely different set of technological difficulties, and raises a series of questions about disposal of nonessential elements. The Newtonian-world vision of a methane burnoff is impractical at the molecular level, and the state of byproduct disposal is unclear at this point. If unwanted matter can be converted to energy, and stored for use, nanotechnology could change the nature of both recycling and of power. If each household ran on a “green power” combination of solar energy and molecular conversions, entire industries might be transformed. It stretches the imagination a bit to think that factories could be powered with wind, solar, and nano power, so the traditional power industries might not disappear, but important sectors might achieve relative independence from them.

At the same time, the intellectual property forces would still work to bind nanobased anything to the existing corporate world. If nano goes “into the wild,” via bootleg or Robin Hood dissemination, it could weaken the corporate hold, inspire a widespread law enforcement crackdown on piracy, or dissolve society into above-ground and Morlock-like subcultures that coexist because they have little reason to compete. In any of these scenarios, nanotechnology by itself is not an actor: it is a tool of other interests, and its impacts are dampened or enhanced by the decisions of social engineering and politics. But if the end result is the alienation of large masses of citizens from the engines of the economy and the icons of government, the costs and secondary developments will be far ranging.

Nanotechnology has its own limits. A host of major decisions in the social realm will not be changed to any great degree by nanotechnology. It will not protect the Arctic Natural Wildlife Refuge (indeed, if natural gas is the first and basic fuel for desktop manufacturing, it may exacerbate the pressures on the ANWR), nor will it stop the denuding of the Amazon rain forest. It will not eliminate prejudice, nor resolve the multiple questions of authority and Authority that attend the modern estate of humankind. We can predict safely that when this particular future of mature nanotechnology arrives, it will not be equally distributed, and may easily be a weapon of social dominance rather than the delivery vehicle of social equity. Even the utopian visions of Gene Roddenberry included a period of troubled dystopia, which Alvin Toffler captured in Future Shock: “the premature arrival of the future… the imposition of a new culture on an old one” that results in “human beings…. increasingly disoriented, progressively incompetent to deal with their environments.”

Which leaves me almost where I began: What do I make of this nanotechnology thing? I suspect it will be very much like its predecessors, a potentially transformative technology that will be bound on the bed of Procrustes of the older social and economic systems that midwifed it. Because of that, it has considerable potential to be more Pandora’s Box than Holy Grail in the early going. Assuming that its byproducts do not poison the groundwater or become an airborne grey goo, it will almost have to achieve an outlaw status (or its more egalitarian potential championed by those who will be deemed outlaws) before it reaches a socially transformative cusp. In the near term, whether I buy it in a store or make it with my nanofactory, I will still have to pay for toilet paper.

Michael Buerger, an Associate Professor of Criminal Justice at Bowling Green State University and a former police officer, is a member of the Futures Working Group, a collaboration between the FBI and the Society of Police Futurists International. His broad interests mainly concern the impact of large-scale social changes and reactions to them.

1 Nanotechnology Perceptions: A Review of Ultraprecision Engineering and Nanotechnology (Collegium Basilea, Basel, Switzerland), Volume 2, Number 1a

2 The Futures Working Group, a collaboration between the FBI and the Society of Police Futurists International (http://www.policefuturists.org/futures/fwg.htm)

3 Global Task Force on Implications and Policy (http://www.crnano.org/CTF.htm), organized by the Center for Responsible Nanotechnology

4 “The Need For Limits” (http://www.kurzweilai.net/the-need-for-limits)

5 The Singularity is Near (http://singularity.com/)