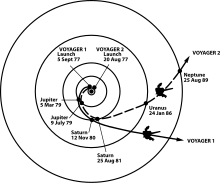

The trajectories that enabled NASA's twin Voyager spacecraft to tour the

four giant planets and achieve velocity to escape the Solar System

In orbital mechanics and aerospace engineering, a gravitational slingshot, gravity assist maneuver, or swing-by is the use of the relative movement (e.g. orbit around the Sun) and gravity of a planet or other astronomical object to alter the path and speed of a spacecraft, typically to save propellant and reduce expense. Gravity assistance can be used to accelerate a spacecraft, that is, to increase or decrease its speed or redirect its path. The "assist" is provided by the motion of the gravitating body as it pulls on the spacecraft.[1] The gravity assist maneuver was first used in 1959 when the Soviet probe Luna 3 photographed the far side of Earth's Moon and it was used by interplanetary probes from Mariner 10 onwards, including the two Voyager probes' notable flybys of Jupiter and Saturn.

Explanation

Example encounter[2]

A gravity assist around a planet changes a spacecraft's velocity (relative to the Sun) by entering and leaving the gravitational sphere of influence of a planet. The spacecraft's speed increases as it approaches the planet and decreases while escaping its gravitational pull (which is approximately the same), but because the planet orbits the Sun the spacecraft is affected by this motion during the maneuver. To increase speed, the spacecraft flies with the movement of the planet (taking a small amount of the planet's orbital energy); to decrease speed, the spacecraft flies against the movement of the planet. The sum of the kinetic energies of both bodies remains constant (see elastic collision). A slingshot maneuver can therefore be used to change the spaceship's trajectory and speed relative to the Sun.

A close terrestrial analogy is provided by a tennis ball bouncing off the front of a moving train. Imagine standing on a train platform, and throwing a ball at 30 km/h toward a train approaching at 50 km/h. The driver of the train sees the ball approaching at 80 km/h and then departing at 80 km/h after the ball bounces elastically off the front of the train. Because of the train's motion, however, that departure is at 130 km/h relative to the train platform; the ball has added twice the train's velocity to its own.

Translating this analogy into space: in the planet reference frame, the spaceship has a vertical velocity of v, while the planet is at rest. After the slingshot occurs and the spaceship leaves the planet, it will still have a velocity of v, but in the horizontal direction, as the effects of gravity cancel out.[2] In the Sun reference frame, the planet has a horizontal velocity of v, and by using the Pythagorean Theorem, the spaceship initially has a total velocity of √2v. After the spaceship leaves the planet, it will have a velocity of v + v = 2v, gaining around 0.6v.[2]

Possible outcomes of a gravity assist maneuver depending on the frame of reference

This oversimplified example is impossible to refine without additional details regarding the orbit, but if the spaceship travels in a path which forms a hyperbola, it can leave the planet in the opposite direction without firing its engine. This example is also one of many trajectories and gained speeds the spaceship can have.

This explanation might seem to violate the conservation of energy and momentum, apparently adding velocity to the spacecraft out of nothing, but the spacecraft's effects on the planet must also be taken into consideration to provide a complete picture of the mechanics involved. The linear momentum gained by the spaceship is equal in magnitude to that lost by the planet, so the spacecraft gains velocity and the planet loses velocity. However, the planet's enormous mass compared to the spacecraft makes the resulting change in its speed negligibly small. These effects on the planet are so slight (because planets are so much more massive than spacecraft) that they can be ignored in the calculation.[3]

Realistic portrayals of encounters in space require the consideration of three dimensions. The same principles apply, only adding the planet's velocity to that of the spacecraft requires vector addition, as shown below.

Two-dimensional schematic of gravitational slingshot. The arrows show

the direction in which the spacecraft is traveling before and after the

encounter. The length of the arrows shows the spacecraft's speed.

A view from MESSENGER as it uses Earth as a gravitational slingshot to

decelerate to allow insertion into an orbit around Mercury.

Due to the reversibility of orbits, gravitational slingshots can also be used to reduce the speed of a spacecraft. Both Mariner 10 and MESSENGER performed this maneuver to reach Mercury.

If even more speed is needed than available from gravity assist alone, the most economical way to utilize a rocket burn is to do it near the periapsis (closest approach). A given rocket burn always provides the same change in velocity (Δv), but the change in kinetic energy is proportional to the vehicle's velocity at the time of the burn. So to get the most kinetic energy from the burn, the burn must occur at the vehicle's maximum velocity, at periapsis. Oberth effect describes this technique in more detail.

Historical origins

In his paper “Тем кто будет читать, чтобы строить” (To those who will be reading [this paper] in order to build [an interplanetary rocket]),[4] published in 1938 but dated 1918–1919,[5] Yuri Kondratyuk suggested that a spacecraft traveling between two planets could be accelerated at the beginning and end of its trajectory by using the gravity of the two planets' moons. In his 1925 paper "Проблема полета при помощи реактивных аппаратов: межпланетные полеты" [Problems of flight by jet propulsion: interplanetary flights],[6] Friedrich Zander made a similar argument.The gravity assist maneuver was first used in 1959 when the Soviet probe Luna 3 photographed the far side of Earth's Moon. The maneuver relied on research performed under the direction of Mstislav Keldysh at the Steklov Institute of Mathematics.[7][8]

Egorov’s work is mentioned in: Boris V. Rauschenbakh, Michael Yu. Ovchinnikov, and Susan M. P. McKenna-Lawlor, Essential Spaceflight Dynamics and Magnetospherics (Dordrecht, Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers, 2002), pages 146–147.[9]

Purpose

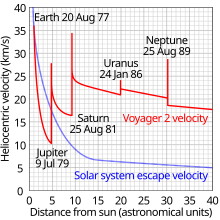

Plot of Voyager 2's heliocentric velocity against its distance from the

Sun, illustrating the use of gravity assist to accelerate the spacecraft

by Jupiter, Saturn and Uranus. To observe Triton,

Voyager 2 passed over Neptune's north pole resulting in an acceleration

out of the plane of the ecliptic and reduced velocity away from the

Sun.[10]

A spacecraft traveling from Earth to an inner planet will increase its relative speed because it is falling toward the Sun, and a spacecraft traveling from Earth to an outer planet will decrease its speed because it is leaving the vicinity of the Sun.

Although the orbital speed of an inner planet is greater than that of the Earth, a spacecraft traveling to an inner planet, even at the minimum speed needed to reach it, is still accelerated by the Sun's gravity to a speed notably greater than the orbital speed of that destination planet. If the spacecraft's purpose is only to fly by the inner planet, then there is typically no need to slow the spacecraft. However, if the spacecraft is to be inserted into orbit about that inner planet, then there must be some way to slow it down.

Similarly, while the orbital speed of an outer planet is less than that of the Earth, a spacecraft leaving the Earth at the minimum speed needed to travel to some outer planet is slowed by the Sun's gravity to a speed far less than the orbital speed of that outer planet. Thus, there must be some way to accelerate the spacecraft when it reaches that outer planet if it is to enter orbit about it. However, if the spacecraft is accelerated to more than the minimum required, less total propellant will be needed to enter orbit about the target planet.[clarification needed][dubious ] In addition, accelerating the spacecraft early in the flight reduces the travel time.

Rocket engines can certainly be used to increase and decrease the speed of the spacecraft. However, rocket thrust takes propellant, propellant has mass, and even a small change in velocity (known as Δv, or "delta-v", the delta symbol being used to represent a change and "v" signifying velocity) translates to a far larger requirement for propellant needed to escape Earth's gravity well. This is because not only must the primary-stage engines lift the extra propellant, they must also lift the extra propellant beyond that, which is needed to lift that additional propellant. Thus the liftoff mass requirement increases exponentially with an increase in the required delta-v of the spacecraft.

Because additional fuel is needed to lift fuel into space, space missions are designed with a tight propellant "budget", known as the "delta-v budget". The delta-v budget is in effect the total propellant that will be available after leaving the earth, for speeding up, slowing down, stabilization against external buffeting (by particles or other external effects), or direction changes, if it cannot acquire more propellant. The entire mission must be planned within that capability. Therefore, methods of speed and direction change that do not require fuel to be burned are advantageous, because they allow extra maneuvering capability and course enhancement, without spending fuel from the limited amount which has been carried into space. Gravity assist manoeuvers can greatly change the speed of a spacecraft without expending propellant, and can save significant amounts of propellant, so they are a very common technique to save fuel.

Examples:

- The Messenger mission used gravity assist maneuvering to slow the spacecraft on its way to Mercury; however, since Mercury has almost no atmosphere, aerobraking could not be used for insertion into orbit around it.

- Journeys to the nearest planets, Mars and Venus, often use a Hohmann transfer orbit, an elliptical path which starts as a tangent to one planet's orbit round the Sun and finishes as a tangent to the other. When other bodies are unavailable for gravity assists, this often takes the minimum amount of propellant.

- Even using a Hohmann transfer orbit, travel to the outer planets (Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune) would require an extremely large delta-v budget and powerful (or very long-burning) rockets to escape the Sun's gravity,

and a very high speed to complete the journey in years rather than

decades. Gravitational assist maneuvers offer a way to gain a very high

speed without using propellant, therefore as of 2017, all missions to

the outer planets have used them.[citation needed]

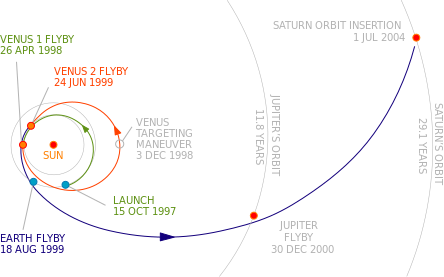

- The 1997 Cassini–Huygens mission to Saturn is an example of a mission to the outer Solar System. It used repeated gravity assist manouvres - Venus twice, and Earth and Jupiter once each - to travel 2.1 billion miles in a little over 6 years, arriving in 2004, which was far faster and more fuel-economical than attempting to travel the "straight line" 0.89 billion miles to Saturn directly without gravitational assistance.

Limits

The Planetary Grand Tour trajectory of Voyager 2

The main practical limit to the use of a gravity assist maneuver is that planets and other large masses are seldom in the right places to enable a voyage to a particular destination. For example, the Voyager missions which started in the late 1970s were made possible by the "Grand Tour" alignment of Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus and Neptune. A similar alignment will not occur again until the middle of the 22nd century. That is an extreme case, but even for less ambitious missions there are years when the planets are scattered in unsuitable parts of their orbits.

Another limitation is the atmosphere, if any, of the available planet. The closer the spacecraft can approach, the faster its periapsis speed as gravity accelerates the spacecraft, allowing for more kinetic energy to be gained from a rocket burn. However, if a spacecraft gets too deep into the atmosphere, the energy lost to drag can exceed that gained from the planet's gravity. On the other hand, the atmosphere can be used to accomplish aerobraking. There have also been theoretical proposals to use aerodynamic lift as the spacecraft flies through the atmosphere. This maneuver, called an aerogravity assist, could bend the trajectory through a larger angle than gravity alone, and hence increase the gain in energy.

Interplanetary slingshots using the Sun itself are not possible because the Sun is at rest relative to the Solar System as a whole. However, thrusting when near the Sun has the same effect as the powered slingshot described as the Oberth effect. This has the potential to magnify a spacecraft's thrusting power enormously, but is limited by the spacecraft's ability to resist the heat.

An interstellar slingshot using the Sun is conceivable, involving for example an object coming from elsewhere in our galaxy and swinging past the Sun to boost its galactic travel. The energy and angular momentum would then come from the Sun's orbit around the Milky Way. This concept features prominently in Arthur C. Clarke's 1972 award-winning novel Rendezvous With Rama; his story concerns an interstellar spacecraft that uses the Sun to perform this sort of maneuver, and in the process alarms many nervous humans.

A rotating black hole might provide additional assistance, if its spin axis is aligned the right way. General relativity predicts that a large spinning mass produces frame-dragging—close to the object, space itself is dragged around in the direction of the spin. Any ordinary rotating object produces this effect. Although attempts to measure frame dragging about the Sun have produced no clear evidence, experiments performed by Gravity Probe B have detected frame-dragging effects caused by Earth.[11] General relativity predicts that a spinning black hole is surrounded by a region of space, called the ergosphere, within which standing still (with respect to the black hole's spin) is impossible, because space itself is dragged at the speed of light in the same direction as the black hole's spin. The Penrose process may offer a way to gain energy from the ergosphere, although it would require the spaceship to dump some "ballast" into the black hole, and the spaceship would have had to expend energy to carry the "ballast" to the black hole.

Timeline of notable examples

Mariner 10 – first use in an interplanetary trajectory

The Mariner 10 probe was the first spacecraft to use the gravitational slingshot effect to reach another planet, passing by Venus on February 5, 1974, on its way to becoming the first spacecraft to explore Mercury.Voyager 1 – farthest human-made object

As of September 18, 2017, Voyager 1 is over 139.9 AU (20.9 billion km) from the Sun,[12] and is in interstellar space.[13] It gained the energy to escape the Sun's gravity completely by performing slingshot maneuvers around Jupiter and Saturn.[14][15]Galileo – a change of plan

The Galileo spacecraft was launched by NASA in 1989 aboard Space Shuttle Atlantis. Its original mission was designed to use a direct Hohmann transfer. However, Galileo's intended booster, the cryogenically fueled Centaur booster rocket was prohibited as a Shuttle "cargo" for safety considerations following the loss of Space Shuttle Challenger. With its substituted solid rocket upper stage, the IUS, which could not provide as much delta-v, Galileo did not ascend directly to Jupiter, but flew by Venus once and Earth twice in order to reach Jupiter in December 1995.The Galileo engineering review speculated (but was never able to prove conclusively) that this longer flight time coupled with the stronger sunlight near Venus caused lubricant in Galileo's main antenna to fail, forcing the use of a much smaller backup antenna with a consequent lowering of data rate from the spacecraft.

Its subsequent tour of the Jovian moons also used numerous slingshot maneuvers with those moons to conserve fuel and maximize the number of encounters.

The Ulysses probe changed the plane of its trajectory

In 1990, NASA launched the ESA spacecraft Ulysses to study the polar regions of the Sun. All the planets orbit approximately in a plane aligned with the equator of the Sun. Thus, to enter an orbit passing over the poles of the Sun, the spacecraft would have to eliminate the 30 km/s speed it inherited from the Earth's orbit around the Sun and gain the speed needed to orbit the Sun in the pole-to-pole plane — tasks that are impossible with current spacecraft propulsion systems alone, making gravity assist maneuvers essential.Accordingly, Ulysses was first sent toward Jupiter, aimed to arrive at a point in space just ahead and south of the planet. As it passed Jupiter, the probe fell through the planet's gravity field, exchanging momentum with the planet. This gravity assist maneuver bent the probe's trajectory northward relative to the Ecliptic Plane onto an orbit which passes over the poles of the Sun. By using this maneuver, Ulysses needed only enough propellant to send it to a point near Jupiter, which is well within current capability.

MESSENGER

The MESSENGER mission (launched in August 2004) made extensive use of gravity assists to slow its speed before orbiting Mercury. The MESSENGER mission included one flyby of Earth, two flybys of Venus, and three flybys of Mercury before finally arriving at Mercury in March 2011 with a velocity low enough to permit orbit insertion with available fuel. Although the flybys were primarily orbital maneuvers, each provided an opportunity for significant scientific observations.The Cassini probe – multiple gravity assists

The Cassini probe passed by Venus twice, then Earth, and finally Jupiter on the way to Saturn. The 6.7-year transit was slightly longer than the six years needed for a Hohmann transfer, but cut the extra velocity (delta-v) needed to about 2 km/s, so that the large and heavy Cassini probe was able to reach Saturn, which would not have been possible in a direct transfer even with the Titan IV, the largest launch vehicle available at the time. A Hohmann transfer to Saturn would require a total of 15.7 km/s delta-v (disregarding Earth's and Saturn's own gravity wells, and disregarding aerobraking), which is not within the capabilities of current launch vehicles and spacecraft propulsion systems.

Cassini's speed related to Sun. The various gravity assists form

visible peaks on the left, while the periodic variation on the right is

caused by the spacecraft's orbit around Saturn. The data was from JPL Horizons Ephemeris System.

The speed above is in kilometers per second. Note also that the minimum

speed achieved during Saturnian orbit is more or less equal to Saturn's

own orbital velocity, which is the ~5 km/s velocity which Cassini

matched to enter orbit.