In physics, a dipole (from Greek δίς (dis) 'twice', and πόλος (polos) 'axis') is an electromagnetic phenomenon which occurs in two ways:

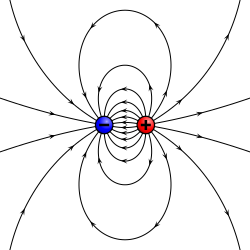

- An electric dipole deals with the separation of the positive and negative electric charges found in any electromagnetic system. A simple example of this system is a pair of charges of equal magnitude but opposite sign separated by some typically small distance. (A permanent electric dipole is called an electret.)

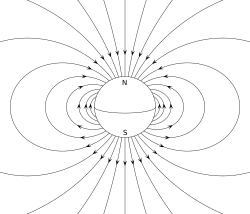

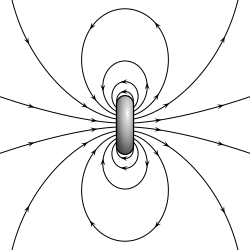

- A magnetic dipole is the closed circulation of an electric current system. A simple example is a single loop of wire with constant current through it. A bar magnet is an example of a magnet with a permanent magnetic dipole moment.

Dipoles, whether electric or magnetic, can be characterized by their dipole moment, a vector quantity. For the simple electric dipole, the electric dipole moment points from the negative charge towards the positive charge, and has a magnitude equal to the strength of each charge times the separation between the charges. (To be precise: for the definition of the dipole moment, one should always consider the "dipole limit", where, for example, the distance of the generating charges should converge to 0 while simultaneously, the charge strength should diverge to infinity in such a way that the product remains a positive constant.)

For the magnetic (dipole) current loop, the magnetic dipole moment points through the loop (according to the right hand grip rule), with a magnitude equal to the current in the loop times the area of the loop.

Similar to magnetic current loops, the electron particle and some other fundamental particles have magnetic dipole moments, as an electron generates a magnetic field identical to that generated by a very small current loop. However, an electron's magnetic dipole moment is not due to a current loop, but to an intrinsic property of the electron. The electron may also have an electric dipole moment though such has yet to be observed (see electron electric dipole moment).

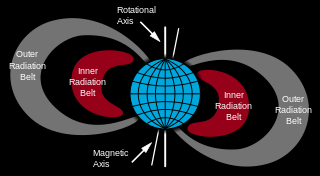

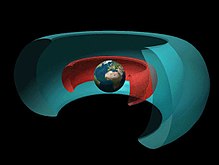

A permanent magnet, such as a bar magnet, owes its magnetism to the intrinsic magnetic dipole moment of the electron. The two ends of a bar magnet are referred to as poles (not to be confused with monopoles, see Classification below) and may be labeled "north" and "south". In terms of the Earth's magnetic field, they are respectively "north-seeking" and "south-seeking" poles: if the magnet were freely suspended in the Earth's magnetic field, the north-seeking pole would point towards the north and the south-seeking pole would point towards the south. The dipole moment of the bar magnet points from its magnetic south to its magnetic north pole. In a magnetic compass, the north pole of a bar magnet points north. However, that means that Earth's geomagnetic north pole is the south pole (south-seeking pole) of its dipole moment and vice versa.

The only known mechanisms for the creation of magnetic dipoles are by current loops or quantum-mechanical spin since the existence of magnetic monopoles has never been experimentally demonstrated.

Classification

A physical dipole consists of two equal and opposite point charges: in the literal sense, two poles. Its field at large distances (i.e., distances large in comparison to the separation of the poles) depends almost entirely on the dipole moment as defined above. A point (electric) dipole is the limit obtained by letting the separation tend to 0 while keeping the dipole moment fixed. The field of a point dipole has a particularly simple form, and the order-1 term in the multipole expansion is precisely the point dipole field.

Although there are no known magnetic monopoles in nature, there are magnetic dipoles in the form of the quantum-mechanical spin associated with particles such as electrons (although the accurate description of such effects falls outside of classical electromagnetism). A theoretical magnetic point dipole has a magnetic field of exactly the same form as the electric field of an electric point dipole. A very small current-carrying loop is approximately a magnetic point dipole; the magnetic dipole moment of such a loop is the product of the current flowing in the loop and the (vector) area of the loop.

Any configuration of charges or currents has a 'dipole moment', which describes the dipole whose field is the best approximation, at large distances, to that of the given configuration. This is simply one term in the multipole expansion when the total charge ("monopole moment") is 0—as it always is for the magnetic case, since there are no magnetic monopoles. The dipole term is the dominant one at large distances: Its field falls off in proportion to 1/r3, as compared to 1/r4 for the next (quadrupole) term and higher powers of 1/r for higher terms, or 1/r2 for the monopole term.

Molecular dipoles

Many molecules have such dipole moments due to non-uniform distributions of positive and negative charges on the various atoms. Such is the case with polar compounds like hydrogen fluoride (HF), where electron density is shared unequally between atoms. Therefore, a molecule's dipole is an electric dipole with an inherent electric field that should not be confused with a magnetic dipole, which generates a magnetic field.

The physical chemist Peter J. W. Debye was the first scientist to study molecular dipoles extensively, and, as a consequence, dipole moments are measured in the non-SI unit named debye in his honor.

For molecules there are three types of dipoles:

- Permanent dipoles

- These occur when two atoms in a molecule have substantially different electronegativity: One atom attracts electrons more than another, becoming more negative, while the other atom becomes more positive. A molecule with a permanent dipole moment is called a polar molecule. See dipole–dipole attractions.

- Instantaneous dipoles

- These occur due to chance when electrons happen to be more concentrated in one place than another in a molecule, creating a temporary dipole. These dipoles are smaller in magnitude than permanent dipoles, but still play a large role in chemistry and biochemistry due to their prevalence. See instantaneous dipole.

- Induced dipoles

- These can occur when one molecule with a permanent dipole repels another molecule's electrons, inducing a dipole moment in that molecule. A molecule is polarized when it carries an induced dipole. See induced-dipole attraction.

More generally, an induced dipole of any polarizable charge distribution ρ (remember that a molecule has a charge distribution) is caused by an electric field external to ρ. This field may, for instance, originate from an ion or polar molecule in the vicinity of ρ or may be macroscopic (e.g., a molecule between the plates of a charged capacitor). The size of the induced dipole moment is equal to the product of the strength of the external field and the dipole polarizability of ρ.

Dipole moment values can be obtained from measurement of the dielectric constant. Some typical gas phase values in debye units are:

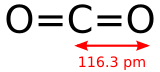

- carbon dioxide: 0

- carbon monoxide: 0.112 D

- ozone: 0.53 D

- phosgene: 1.17 D

- NH3 has a dipole moment of 1.42 D

- water vapor: 1.85 D

- hydrogen cyanide: 2.98 D

- cyanamide: 4.27 D

- potassium bromide: 10.41 D

Potassium bromide (KBr) has one of the highest dipole moments because it is an ionic compound that exists as a molecule in the gas phase.

The overall dipole moment of a molecule may be approximated as a vector sum of bond dipole moments. As a vector sum it depends on the relative orientation of the bonds, so that from the dipole moment information can be deduced about the molecular geometry.

For example, the zero dipole of CO2 implies that the two C=O bond dipole moments cancel so that the molecule must be linear. For H2O the O−H bond moments do not cancel because the molecule is bent. For ozone (O3) which is also a bent molecule, the bond dipole moments are not zero even though the O−O bonds are between similar atoms. This agrees with the Lewis structures for the resonance forms of ozone which show a positive charge on the central oxygen atom.

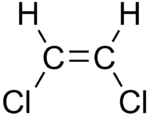

An example in organic chemistry of the role of geometry in determining dipole moment is the cis and trans isomers of 1,2-dichloroethene. In the cis isomer the two polar C−Cl bonds are on the same side of the C=C double bond and the molecular dipole moment is 1.90 D. In the trans isomer, the dipole moment is zero because the two C−Cl bonds are on opposite sides of the C=C and cancel (and the two bond moments for the much less polar C−H bonds also cancel).

Another example of the role of molecular geometry is boron trifluoride, which has three polar bonds with a difference in electronegativity greater than the traditionally cited threshold of 1.7 for ionic bonding. However, due to the equilateral triangular distribution of the fluoride ions centered on and in the same plane as the boron cation, the symmetry of the molecule results in its dipole moment being zero.

Quantum mechanical dipole operator

Consider a collection of N particles with charges qi and position vectors ri. For instance, this collection may be a molecule consisting of electrons, all with charge −e, and nuclei with charge eZi, where Zi is the atomic number of the i th nucleus. The dipole observable (physical quantity) has the quantum mechanical dipole operator:

Notice that this definition is valid only for neutral atoms or molecules, i.e. total charge equal to zero. In the ionized case, we have

where is the center of mass of the molecule/group of particles.

Atomic dipoles

A non-degenerate (S-state) atom can have only a zero permanent dipole. This fact follows quantum mechanically from the inversion symmetry of atoms. All 3 components of the dipole operator are antisymmetric under inversion with respect to the nucleus,

where is the dipole operator and is the inversion operator.

The permanent dipole moment of an atom in a non-degenerate state (see degenerate energy level) is given as the expectation (average) value of the dipole operator,

where is an S-state, non-degenerate, wavefunction, which is symmetric or antisymmetric under inversion: . Since the product of the wavefunction (in the ket) and its complex conjugate (in the bra) is always symmetric under inversion and its inverse,

it follows that the expectation value changes sign under inversion. We used here the fact that , being a symmetry operator, is unitary: and by definition the Hermitian adjoint may be moved from bra to ket and then becomes . Since the only quantity that is equal to minus itself is the zero, the expectation value vanishes,

In the case of open-shell atoms with degenerate energy levels, one could define a dipole moment by the aid of the first-order Stark effect. This gives a non-vanishing dipole (by definition proportional to a non-vanishing first-order Stark shift) only if some of the wavefunctions belonging to the degenerate energies have opposite parity; i.e., have different behavior under inversion. This is a rare occurrence, but happens for the excited H-atom, where 2s and 2p states are "accidentally" degenerate (see article Laplace–Runge–Lenz vector for the origin of this degeneracy) and have opposite parity (2s is even and 2p is odd).

Field of a static magnetic dipole

Magnitude

The far-field strength, B, of a dipole magnetic field is given by

where

- B is the strength of the field, measured in teslas

- r is the distance from the center, measured in metres

- λ is the magnetic latitude (equal to 90° − θ) where θ is the magnetic colatitude, measured in radians or degrees from the dipole axis

- m is the dipole moment, measured in ampere-square metres or joules per tesla

- μ0 is the permeability of free space, measured in henries per metre.

Conversion to cylindrical coordinates is achieved using r2 = z2 + ρ2 and

where ρ is the perpendicular distance from the z-axis. Then,

Vector form

The field itself is a vector quantity:

where

- B is the field

- r is the vector from the position of the dipole to the position where the field is being measured

- r is the absolute value of r: the distance from the dipole

- r̂ = r/r is the unit vector parallel to r;

- m is the (vector) dipole moment

- μ0 is the permeability of free space

This is exactly the field of a point dipole, exactly the dipole term in the multipole expansion of an arbitrary field, and approximately the field of any dipole-like configuration at large distances.

Magnetic vector potential

The vector potential A of a magnetic dipole is

with the same definitions as above.

Field from an electric dipole

The electrostatic potential at position r due to an electric dipole at the origin is given by:

where p is the (vector) dipole moment, and є0 is the permittivity of free space.

This term appears as the second term in the multipole expansion of an arbitrary electrostatic potential Φ(r). If the source of Φ(r) is a dipole, as it is assumed here, this term is the only non-vanishing term in the multipole expansion of Φ(r). The electric field from a dipole can be found from the gradient of this potential:

This is of the same form of the expression for the magnetic field of a point magnetic dipole, ignoring the delta function. In a real electric dipole, however, the charges are physically separate and the electric field diverges or converges at the point charges. This is different to the magnetic field of a real magnetic dipole which is continuous everywhere. The delta function represents the strong field pointing in the opposite direction between the point charges, which is often omitted since one is rarely interested in the field at the dipole's position. For further discussions about the internal field of dipoles, see or Magnetic moment#Internal magnetic field of a dipole.

Torque on a dipole

Since the direction of an electric field is defined as the direction of the force on a positive charge, electric field lines point away from a positive charge and toward a negative charge.

When placed in a homogeneous electric or magnetic field, equal but opposite forces arise on each side of the dipole creating a torque τ}:

for an electric dipole moment p (in coulomb-meters), or

for a magnetic dipole moment m (in ampere-square meters).

The resulting torque will tend to align the dipole with the applied field, which in the case of an electric dipole, yields a potential energy of

- .

The energy of a magnetic dipole is similarly

- .

Dipole radiation

In addition to dipoles in electrostatics, it is also common to consider an electric or magnetic dipole that is oscillating in time. It is an extension, or a more physical next-step, to spherical wave radiation.

In particular, consider a harmonically oscillating electric dipole, with angular frequency ω and a dipole moment p0 along the ẑ direction of the form

In vacuum, the exact field produced by this oscillating dipole can be derived using the retarded potential formulation as:

For rω/c ≫ 1, the far-field takes the simpler form of a radiating "spherical" wave, but with angular dependence embedded in the cross-product:

The time-averaged Poynting vector

is not distributed isotropically, but concentrated around the directions lying perpendicular to the dipole moment, as a result of the non-spherical electric and magnetic waves. In fact, the spherical harmonic function (sin θ) responsible for such toroidal angular distribution is precisely the l = 1 "p" wave.

The total time-average power radiated by the field can then be derived from the Poynting vector as

Notice that the dependence of the power on the fourth power of the frequency of the radiation is in accordance with the Rayleigh scattering, and the underlying effects why the sky consists of mainly blue colour.

A circular polarized dipole is described as a superposition of two linear dipoles.

![{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}\mathbf {E} &={\frac {1}{4\pi \varepsilon _{0}}}\left\{{\frac {\omega ^{2}}{c^{2}r}}\left({\hat {\mathbf {r} }}\times \mathbf {p} \right)\times {\hat {\mathbf {r} }}+\left({\frac {1}{r^{3}}}-{\frac {i\omega }{cr^{2}}}\right)\left(3{\hat {\mathbf {r} }}\left[{\hat {\mathbf {r} }}\cdot \mathbf {p} \right]-\mathbf {p} \right)\right\}e^{\frac {i\omega r}{c}}e^{-i\omega t}\\\mathbf {B} &={\frac {\omega ^{2}}{4\pi \varepsilon _{0}c^{3}}}({\hat {\mathbf {r} }}\times \mathbf {p} )\left(1-{\frac {c}{i\omega r}}\right){\frac {e^{i\omega r/c}}{r}}e^{-i\omega t}.\end{aligned}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/4a84ead8e373689b51cea6ced6348616d2201bd6)