The Hubble Ultra-Deep Field image shows some of the most remote galaxies visible with present technology, each consisting of billions of stars. (Apparent image area about 1/79 that of a full moon) | |

| Age (within Lambda-CDM model) | 13.799 ± 0.021 billion years |

|---|---|

| Diameter | Unknown. Diameter of the observable universe: 8.8×1026 m (28.5 Gpc or 93 Gly) |

| Mass (ordinary matter) | At least 1053 kg |

| Average density (including the contribution from energy) | 9.9 x 10−30 g/cm3 |

| Average temperature | 2.72548 K (-270.4 °C or -454.8 °F) |

| Main contents | Ordinary (baryonic) matter (4.9%) Dark matter (26.8%) Dark energy (68.3%) |

| Shape | Flat with a 0.4% margin of error |

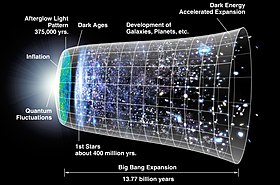

The universe (Latin: universus) is all of space and time and their contents, including planets, stars, galaxies, and all other forms of matter and energy. The Big Bang theory is the prevailing cosmological description of the development of the universe. According to this theory, space and time emerged together 13.787±0.020 billion years ago, and the universe has been expanding ever since. While the spatial size of the entire universe is unknown, the cosmic inflation equation indicates that it must have a minimum diameter of 23 trillion light years, and it is possible to measure the size of the observable universe, which is approximately 93 billion light-years in diameter at the present day.

The earliest cosmological models of the universe were developed by ancient Greek and Indian philosophers and were geocentric, placing Earth at the center. Over the centuries, more precise astronomical observations led Nicolaus Copernicus to develop the heliocentric model with the Sun at the center of the Solar System. In developing the law of universal gravitation, Isaac Newton built upon Copernicus's work as well as Johannes Kepler's laws of planetary motion and observations by Tycho Brahe.

Further observational improvements led to the realization that the Sun is one of hundreds of billions of stars in the Milky Way, which is one of a few hundred billion galaxies in the universe. Many of the stars in a galaxy have planets. At the largest scale, galaxies are distributed uniformly and the same in all directions, meaning that the universe has neither an edge nor a center. At smaller scales, galaxies are distributed in clusters and superclusters which form immense filaments and voids in space, creating a vast foam-like structure. Discoveries in the early 20th century have suggested that the universe had a beginning and that space has been expanding since then at an increasing rate.

According to the Big Bang theory, the energy and matter initially present have become less dense as the universe expanded. After an initial accelerated expansion called the inflationary epoch at around 10−32 seconds, and the separation of the four known fundamental forces, the universe gradually cooled and continued to expand, allowing the first subatomic particles and simple atoms to form. Dark matter gradually gathered, forming a foam-like structure of filaments and voids under the influence of gravity. Giant clouds of hydrogen and helium were gradually drawn to the places where dark matter was most dense, forming the first galaxies, stars, and everything else seen today.

From studying the movement of galaxies, it has been discovered that the universe contains much more matter than is accounted for by visible objects; stars, galaxies, nebulas and interstellar gas. This unseen matter is known as dark matter (dark means that there is a wide range of strong indirect evidence that it exists, but we have not yet detected it directly). The ΛCDM model is the most widely accepted model of the universe. It suggests that about 69.2%±1.2% [2015] of the mass and energy in the universe is a cosmological constant (or, in extensions to ΛCDM, other forms of dark energy, such as a scalar field) which is responsible for the current expansion of space, and about 25.8%±1.1% [2015] is dark matter. Ordinary ('baryonic') matter is therefore only 4.84%±0.1% [2015] of the physical universe. Stars, planets, and visible gas clouds only form about 6% of the ordinary matter.

There are many competing hypotheses about the ultimate fate of the universe and about what, if anything, preceded the Big Bang, while other physicists and philosophers refuse to speculate, doubting that information about prior states will ever be accessible. Some physicists have suggested various multiverse hypotheses, in which our universe might be one among many universes that likewise exist.

| Physical cosmology |

|---|

|

Definition

(video 00:50; May 2, 2019)

The physical universe is defined as all of space and time (collectively referred to as spacetime) and their contents. Such contents comprise all of energy in its various forms, including electromagnetic radiation and matter, and therefore planets, moons, stars, galaxies, and the contents of intergalactic space. The universe also includes the physical laws that influence energy and matter, such as conservation laws, classical mechanics, and relativity.

The universe is often defined as "the totality of existence", or everything that exists, everything that has existed, and everything that will exist. In fact, some philosophers and scientists support the inclusion of ideas and abstract concepts—such as mathematics and logic—in the definition of the universe. The word universe may also refer to concepts such as the cosmos, the world, and nature.

Etymology

The word universe derives from the Old French word univers, which in turn derives from the Latin word universum. The Latin word was used by Cicero and later Latin authors in many of the same senses as the modern English word is used.

Synonyms

A term for universe among the ancient Greek philosophers from Pythagoras onwards was τὸ πᾶν (tò pân) 'the all', defined as all matter and all space, and τὸ ὅλον (tò hólon) 'all things', which did not necessarily include the void. Another synonym was ὁ κόσμος (ho kósmos) meaning 'the world, the cosmos'. Synonyms are also found in Latin authors (totum, mundus, natura) and survive in modern languages, e.g., the German words Das All, Weltall, and Natur for universe. The same synonyms are found in English, such as everything (as in the theory of everything), the cosmos (as in cosmology), the world (as in the many-worlds interpretation), and nature (as in natural laws or natural philosophy).

Chronology and the Big Bang

−13 — – −12 — – −11 — – −10 — – −9 — – −8 — – −7 — – −6 — – −5 — – −4 — – −3 — – −2 — – −1 — – 0 — |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The prevailing model for the evolution of the universe is the Big Bang theory. The Big Bang model states that the earliest state of the universe was an extremely hot and dense one, and that the universe subsequently expanded and cooled. The model is based on general relativity and on simplifying assumptions such as the homogeneity and isotropy of space. A version of the model with a cosmological constant (Lambda) and cold dark matter, known as the Lambda-CDM model, is the simplest model that provides a reasonably good account of various observations about the universe. The Big Bang model accounts for observations such as the correlation of distance and redshift of galaxies, the ratio of the number of hydrogen to helium atoms, and the microwave radiation background.

The initial hot, dense state is called the Planck epoch, a brief period extending from time zero to one Planck time unit of approximately 10−43 seconds. During the Planck epoch, all types of matter and all types of energy were concentrated into a dense state, and gravity—currently the weakest by far of the four known forces—is believed to have been as strong as the other fundamental forces, and all the forces may have been unified. Since the Planck epoch, space has been expanding to its present scale, with a very short but intense period of cosmic inflation believed to have occurred within the first 10−32 seconds. This was a kind of expansion different from those we can see around us today. Objects in space did not physically move; instead the metric that defines space itself changed. Although objects in spacetime cannot move faster than the speed of light, this limitation does not apply to the metric governing spacetime itself. This initial period of inflation is believed to explain why space appears to be very flat, and much larger than light could travel since the start of the universe.

Within the first fraction of a second of the universe's existence, the four fundamental forces had separated. As the universe continued to cool down from its inconceivably hot state, various types of subatomic particles were able to form in short periods of time known as the quark epoch, the hadron epoch, and the lepton epoch. Together, these epochs encompassed less than 10 seconds of time following the Big Bang. These elementary particles associated stably into ever larger combinations, including stable protons and neutrons, which then formed more complex atomic nuclei through nuclear fusion. This process, known as Big Bang nucleosynthesis, only lasted for about 17 minutes and ended about 20 minutes after the Big Bang, so only the fastest and simplest reactions occurred. About 25% of the protons and all the neutrons in the universe, by mass, were converted to helium, with small amounts of deuterium (a form of hydrogen) and traces of lithium. Any other element was only formed in very tiny quantities. The other 75% of the protons remained unaffected, as hydrogen nuclei.

After nucleosynthesis ended, the universe entered a period known as the photon epoch. During this period, the universe was still far too hot for matter to form neutral atoms, so it contained a hot, dense, foggy plasma of negatively charged electrons, neutral neutrinos and positive nuclei. After about 377,000 years, the universe had cooled enough that electrons and nuclei could form the first stable atoms. This is known as recombination for historical reasons; in fact electrons and nuclei were combining for the first time. Unlike plasma, neutral atoms are transparent to many wavelengths of light, so for the first time the universe also became transparent. The photons released ("decoupled") when these atoms formed can still be seen today; they form the cosmic microwave background (CMB).

As the universe expands, the energy density of electromagnetic radiation decreases more quickly than does that of matter because the energy of a photon decreases with its wavelength. At around 47,000 years, the energy density of matter became larger than that of photons and neutrinos, and began to dominate the large scale behavior of the universe. This marked the end of the radiation-dominated era and the start of the matter-dominated era.

In the earliest stages of the universe, tiny fluctuations within the universe's density led to concentrations of dark matter gradually forming. Ordinary matter, attracted to these by gravity, formed large gas clouds and eventually, stars and galaxies, where the dark matter was most dense, and voids where it was least dense. After around 100 – 300 million years, the first stars formed, known as Population III stars. These were probably very massive, luminous, non metallic and short-lived. They were responsible for the gradual reionization of the universe between about 200-500 million years and 1 billion years, and also for seeding the universe with elements heavier than helium, through stellar nucleosynthesis. The universe also contains a mysterious energy—possibly a scalar field—called dark energy, the density of which does not change over time. After about 9.8 billion years, the universe had expanded sufficiently so that the density of matter was less than the density of dark energy, marking the beginning of the present dark-energy-dominated era. In this era, the expansion of the universe is accelerating due to dark energy.

Physical properties

Of the four fundamental interactions, gravitation is the dominant at astronomical length scales. Gravity's effects are cumulative; by contrast, the effects of positive and negative charges tend to cancel one another, making electromagnetism relatively insignificant on astronomical length scales. The remaining two interactions, the weak and strong nuclear forces, decline very rapidly with distance; their effects are confined mainly to sub-atomic length scales.

The universe appears to have much more matter than antimatter, an asymmetry possibly related to the CP violation. This imbalance between matter and antimatter is partially responsible for the existence of all matter existing today, since matter and antimatter, if equally produced at the Big Bang, would have completely annihilated each other and left only photons as a result of their interaction. The universe also appears to have neither net momentum nor angular momentum, which follows accepted physical laws if the universe is finite. These laws are Gauss's law and the non-divergence of the stress-energy-momentum pseudotensor.

Size and regions

According to the general theory of relativity, far regions of space may never interact with ours even in the lifetime of the universe due to the finite speed of light and the ongoing expansion of space. For example, radio messages sent from Earth may never reach some regions of space, even if the universe were to exist forever: space may expand faster than light can traverse it.

The spatial region that can be observed with telescopes is called the observable universe, which depends on the location of the observer. The proper distance—the distance as would be measured at a specific time, including the present—between Earth and the edge of the observable universe is 46 billion light-years (14 billion parsecs), making the diameter of the observable universe about 93 billion light-years (28 billion parsecs). The distance the light from the edge of the observable universe has travelled is very close to the age of the universe times the speed of light, 13.8 billion light-years (4.2×109 pc), but this does not represent the distance at any given time because the edge of the observable universe and the Earth have since moved further apart. For comparison, the diameter of a typical galaxy is 30,000 light-years (9,198 parsecs), and the typical distance between two neighboring galaxies is 3 million light-years (919.8 kiloparsecs). As an example, the Milky Way is roughly 100,000–180,000 light-years in diameter, and the nearest sister galaxy to the Milky Way, the Andromeda Galaxy, is located roughly 2.5 million light-years away.

Because we cannot observe space beyond the edge of the observable universe, it is unknown whether the size of the universe in its totality is finite or infinite. Estimates suggest that the whole universe, if finite, must be more than 250 times larger than the observable universe. Some disputed estimates for the total size of the universe, if finite, reach as high as megaparsecs, as implied by a suggested resolution of the No-Boundary Proposal.

Age and expansion

Astronomers calculate the age of the universe by assuming that the Lambda-CDM model accurately describes the evolution of the Universe from a very uniform, hot, dense primordial state to its present state and measuring the cosmological parameters which constitute the model. This model is well understood theoretically and supported by recent high-precision astronomical observations such as WMAP and Planck. Commonly, the set of observations fitted includes the cosmic microwave background anisotropy, the brightness/redshift relation for Type Ia supernovae, and large-scale galaxy clustering including the baryon acoustic oscillation feature. Other observations, such as the Hubble constant, the abundance of galaxy clusters, weak gravitational lensing and globular cluster ages, are generally consistent with these, providing a check of the model, but are less accurately measured at present. Assuming that the Lambda-CDM model is correct, the measurements of the parameters using a variety of techniques by numerous experiments yield a best value of the age of the universe as of 2015 of 13.799 ± 0.021 billion years.

Over time, the universe and its contents have evolved; for example, the relative population of quasars and galaxies has changed and space itself has expanded. Due to this expansion, scientists on Earth can observe the light from a galaxy 30 billion light-years away even though that light has traveled for only 13 billion years; the very space between them has expanded. This expansion is consistent with the observation that the light from distant galaxies has been redshifted; the photons emitted have been stretched to longer wavelengths and lower frequency during their journey. Analyses of Type Ia supernovae indicate that the spatial expansion is accelerating.

The more matter there is in the universe, the stronger the mutual gravitational pull of the matter. If the universe were too dense then it would re-collapse into a gravitational singularity. However, if the universe contained too little matter then the self-gravity would be too weak for astronomical structures, like galaxies or planets, to form. Since the Big Bang, the universe has expanded monotonically. Perhaps unsurprisingly, our universe has just the right mass-energy density, equivalent to about 5 protons per cubic metre, which has allowed it to expand for the last 13.8 billion years, giving time to form the universe as observed today.

There are dynamical forces acting on the particles in the universe which affect the expansion rate. Before 1998, it was expected that the expansion rate would be decreasing as time went on due to the influence of gravitational interactions in the universe; and thus there is an additional observable quantity in the universe called the deceleration parameter, which most cosmologists expected to be positive and related to the matter density of the universe. In 1998, the deceleration parameter was measured by two different groups to be negative, approximately -0.55, which technically implies that the second derivative of the cosmic scale factor has been positive in the last 5-6 billion years. This acceleration does not, however, imply that the Hubble parameter is currently increasing; see deceleration parameter for details.

Spacetime

Spacetimes are the arenas in which all physical events take place. The basic elements of spacetimes are events. In any given spacetime, an event is defined as a unique position at a unique time. A spacetime is the union of all events (in the same way that a line is the union of all of its points), formally organized into a manifold.

Events, such as matter and energy, bend spacetime. Curved spacetime, on the other hand, forces matter and energy to behave in a certain way. There is no point in considering one without the other.

The universe appears to be a smooth spacetime continuum consisting of three spatial dimensions and one temporal (time) dimension (an event in the spacetime of the physical universe can therefore be identified by a set of four coordinates: (x, y, z, t) ). On average, space is observed to be very nearly flat (with a curvature close to zero), meaning that Euclidean geometry is empirically true with high accuracy throughout most of the Universe. Spacetime also appears to have a simply connected topology, in analogy with a sphere, at least on the length-scale of the observable universe. However, present observations cannot exclude the possibilities that the universe has more dimensions (which is postulated by theories such as the string theory) and that its spacetime may have a multiply connected global topology, in analogy with the cylindrical or toroidal topologies of two-dimensional spaces. The spacetime of the universe is usually interpreted from a Euclidean perspective, with space as consisting of three dimensions, and time as consisting of one dimension, the "fourth dimension". By combining space and time into a single manifold called Minkowski space, physicists have simplified a large number of physical theories, as well as described in a more uniform way the workings of the universe at both the supergalactic and subatomic levels.

Spacetime events are not absolutely defined spatially and temporally but rather are known to be relative to the motion of an observer. Minkowski space approximates the universe without gravity; the pseudo-Riemannian manifolds of general relativity describe spacetime with matter and gravity.

Shape

General relativity describes how spacetime is curved and bent by mass and energy (gravity). The topology or geometry of the universe includes both local geometry in the observable universe and global geometry. Cosmologists often work with a given space-like slice of spacetime called the comoving coordinates. The section of spacetime which can be observed is the backward light cone, which delimits the cosmological horizon. The cosmological horizon (also called the particle horizon or the light horizon) is the maximum distance from which particles can have traveled to the observer in the age of the universe. This horizon represents the boundary between the observable and the unobservable regions of the universe. The existence, properties, and significance of a cosmological horizon depend on the particular cosmological model.

An important parameter determining the future evolution of the universe theory is the density parameter, Omega (Ω), defined as the average matter density of the universe divided by a critical value of that density. This selects one of three possible geometries depending on whether Ω is equal to, less than, or greater than 1. These are called, respectively, the flat, open and closed universes.

Observations, including the Cosmic Background Explorer (COBE), Wilkinson Microwave Anisotropy Probe (WMAP), and Planck maps of the CMB, suggest that the universe is infinite in extent with a finite age, as described by the Friedmann–Lemaître–Robertson–Walker (FLRW) models. These FLRW models thus support inflationary models and the standard model of cosmology, describing a flat, homogeneous universe presently dominated by dark matter and dark energy.

Support of life

The universe may be fine-tuned; the Fine-tuned universe hypothesis is the proposition that the conditions that allow the existence of observable life in the universe can only occur when certain universal fundamental physical constants lie within a very narrow range of values, so that if any of several fundamental constants were only slightly different, the universe would have been unlikely to be conducive to the establishment and development of matter, astronomical structures, elemental diversity, or life as it is understood. The proposition is discussed among philosophers, scientists, theologians, and proponents of creationism.

Composition

The universe is composed almost completely of dark energy, dark matter, and ordinary matter. Other contents are electromagnetic radiation (estimated to constitute from 0.005% to close to 0.01% of the total mass-energy of the universe) and antimatter.

The proportions of all types of matter and energy have changed over the history of the universe. The total amount of electromagnetic radiation generated within the universe has decreased by 1/2 in the past 2 billion years. Today, ordinary matter, which includes atoms, stars, galaxies, and life, accounts for only 4.9% of the contents of the Universe. The present overall density of this type of matter is very low, roughly 4.5 × 10−31 grams per cubic centimetre, corresponding to a density of the order of only one proton for every four cubic metres of volume. The nature of both dark energy and dark matter is unknown. Dark matter, a mysterious form of matter that has not yet been identified, accounts for 26.8% of the cosmic contents. Dark energy, which is the energy of empty space and is causing the expansion of the universe to accelerate, accounts for the remaining 68.3% of the contents.

Matter, dark matter, and dark energy are distributed homogeneously throughout the universe over length scales longer than 300 million light-years or so. However, over shorter length-scales, matter tends to clump hierarchically; many atoms are condensed into stars, most stars into galaxies, most galaxies into clusters, superclusters and, finally, large-scale galactic filaments. The observable universe contains as many as 200 billion galaxies and, overall, as many as an estimated 1×1024 stars (more stars than all the grains of sand on planet Earth). Typical galaxies range from dwarfs with as few as ten million (107) stars up to giants with one trillion (1012) stars. Between the larger structures are voids, which are typically 10–150 Mpc (33 million–490 million ly) in diameter. The Milky Way is in the Local Group of galaxies, which in turn is in the Laniakea Supercluster. This supercluster spans over 500 million light-years, while the Local Group spans over 10 million light-years. The Universe also has vast regions of relative emptiness; the largest known void measures 1.8 billion ly (550 Mpc) across.

The observable universe is isotropic on scales significantly larger than superclusters, meaning that the statistical properties of the universe are the same in all directions as observed from Earth. The universe is bathed in highly isotropic microwave radiation that corresponds to a thermal equilibrium blackbody spectrum of roughly 2.72548 kelvins. The hypothesis that the large-scale universe is homogeneous and isotropic is known as the cosmological principle. A universe that is both homogeneous and isotropic looks the same from all vantage points and has no center.

Dark energy

An explanation for why the expansion of the universe is accelerating remains elusive. It is often attributed to "dark energy", an unknown form of energy that is hypothesized to permeate space. On a mass–energy equivalence basis, the density of dark energy (~ 7 × 10−30 g/cm3) is much less than the density of ordinary matter or dark matter within galaxies. However, in the present dark-energy era, it dominates the mass–energy of the universe because it is uniform across space.

Two proposed forms for dark energy are the cosmological constant, a constant energy density filling space homogeneously, and scalar fields such as quintessence or moduli, dynamic quantities whose energy density can vary in time and space. Contributions from scalar fields that are constant in space are usually also included in the cosmological constant. The cosmological constant can be formulated to be equivalent to vacuum energy. Scalar fields having only a slight amount of spatial inhomogeneity would be difficult to distinguish from a cosmological constant.

Dark matter

Dark matter is a hypothetical kind of matter that is invisible to the entire electromagnetic spectrum, but which accounts for most of the matter in the universe. The existence and properties of dark matter are inferred from its gravitational effects on visible matter, radiation, and the large-scale structure of the universe. Other than neutrinos, a form of hot dark matter, dark matter has not been detected directly, making it one of the greatest mysteries in modern astrophysics. Dark matter neither emits nor absorbs light or any other electromagnetic radiation at any significant level. Dark matter is estimated to constitute 26.8% of the total mass–energy and 84.5% of the total matter in the universe.

Ordinary matter

The remaining 4.9% of the mass–energy of the universe is ordinary matter, that is, atoms, ions, electrons and the objects they form. This matter includes stars, which produce nearly all of the light we see from galaxies, as well as interstellar gas in the interstellar and intergalactic media, planets, and all the objects from everyday life that we can bump into, touch or squeeze. As a matter of fact, the great majority of ordinary matter in the universe is unseen, since visible stars and gas inside galaxies and clusters account for less than 10 per cent of the ordinary matter contribution to the mass-energy density of the universe.

Ordinary matter commonly exists in four states (or phases): solid, liquid, gas, and plasma. However, advances in experimental techniques have revealed other previously theoretical phases, such as Bose–Einstein condensates and fermionic condensates.

Ordinary matter is composed of two types of elementary particles: quarks and leptons. For example, the proton is formed of two up quarks and one down quark; the neutron is formed of two down quarks and one up quark; and the electron is a kind of lepton. An atom consists of an atomic nucleus, made up of protons and neutrons, and electrons that orbit the nucleus. Because most of the mass of an atom is concentrated in its nucleus, which is made up of baryons, astronomers often use the term baryonic matter to describe ordinary matter, although a small fraction of this "baryonic matter" is electrons.

Soon after the Big Bang, primordial protons and neutrons formed from the quark–gluon plasma of the early universe as it cooled below two trillion degrees. A few minutes later, in a process known as Big Bang nucleosynthesis, nuclei formed from the primordial protons and neutrons. This nucleosynthesis formed lighter elements, those with small atomic numbers up to lithium and beryllium, but the abundance of heavier elements dropped off sharply with increasing atomic number. Some boron may have been formed at this time, but the next heavier element, carbon, was not formed in significant amounts. Big Bang nucleosynthesis shut down after about 20 minutes due to the rapid drop in temperature and density of the expanding universe. Subsequent formation of heavier elements resulted from stellar nucleosynthesis and supernova nucleosynthesis.

Particles

Ordinary matter and the forces that act on matter can be described in terms of elementary particles. These particles are sometimes described as being fundamental, since they have an unknown substructure, and it is unknown whether or not they are composed of smaller and even more fundamental particles. Of central importance is the Standard Model, a theory that is concerned with electromagnetic interactions and the weak and strong nuclear interactions. The Standard Model is supported by the experimental confirmation of the existence of particles that compose matter: quarks and leptons, and their corresponding "antimatter" duals, as well as the force particles that mediate interactions: the photon, the W and Z bosons, and the gluon. The Standard Model predicted the existence of the recently discovered Higgs boson, a particle that is a manifestation of a field within the universe that can endow particles with mass. Because of its success in explaining a wide variety of experimental results, the Standard Model is sometimes regarded as a "theory of almost everything". The Standard Model does not, however, accommodate gravity. A true force-particle "theory of everything" has not been attained.

Hadrons

A hadron is a composite particle made of quarks held together by the strong force. Hadrons are categorized into two families: baryons (such as protons and neutrons) made of three quarks, and mesons (such as pions) made of one quark and one antiquark. Of the hadrons, protons are stable, and neutrons bound within atomic nuclei are stable. Other hadrons are unstable under ordinary conditions and are thus insignificant constituents of the modern universe. From approximately 10−6 seconds after the Big Bang, during a period is known as the hadron epoch, the temperature of the universe had fallen sufficiently to allow quarks to bind together into hadrons, and the mass of the universe was dominated by hadrons. Initially, the temperature was high enough to allow the formation of hadron/anti-hadron pairs, which kept matter and antimatter in thermal equilibrium. However, as the temperature of the universe continued to fall, hadron/anti-hadron pairs were no longer produced. Most of the hadrons and anti-hadrons were then eliminated in particle-antiparticle annihilation reactions, leaving a small residual of hadrons by the time the universe was about one second old.

Leptons

A lepton is an elementary, half-integer spin particle that does not undergo strong interactions but is subject to the Pauli exclusion principle; no two leptons of the same species can be in exactly the same state at the same time. Two main classes of leptons exist: charged leptons (also known as the electron-like leptons), and neutral leptons (better known as neutrinos). Electrons are stable and the most common charged lepton in the universe, whereas muons and taus are unstable particle that quickly decay after being produced in high energy collisions, such as those involving cosmic rays or carried out in particle accelerators. Charged leptons can combine with other particles to form various composite particles such as atoms and positronium. The electron governs nearly all of chemistry, as it is found in atoms and is directly tied to all chemical properties. Neutrinos rarely interact with anything, and are consequently rarely observed. Neutrinos stream throughout the universe but rarely interact with normal matter.

The lepton epoch was the period in the evolution of the early universe in which the leptons dominated the mass of the universe. It started roughly 1 second after the Big Bang, after the majority of hadrons and anti-hadrons annihilated each other at the end of the hadron epoch. During the lepton epoch the temperature of the universe was still high enough to create lepton/anti-lepton pairs, so leptons and anti-leptons were in thermal equilibrium. Approximately 10 seconds after the Big Bang, the temperature of the universe had fallen to the point where lepton/anti-lepton pairs were no longer created. Most leptons and anti-leptons were then eliminated in annihilation reactions, leaving a small residue of leptons. The mass of the universe was then dominated by photons as it entered the following photon epoch.

Photons

A photon is the quantum of light and all other forms of electromagnetic radiation. It is the force carrier for the electromagnetic force, even when static via virtual photons. The effects of this force are easily observable at the microscopic and at the macroscopic level because the photon has zero rest mass; this allows long distance interactions. Like all elementary particles, photons are currently best explained by quantum mechanics and exhibit wave–particle duality, exhibiting properties of waves and of particles.

The photon epoch started after most leptons and anti-leptons were annihilated at the end of the lepton epoch, about 10 seconds after the Big Bang. Atomic nuclei were created in the process of nucleosynthesis which occurred during the first few minutes of the photon epoch. For the remainder of the photon epoch the universe contained a hot dense plasma of nuclei, electrons and photons. About 380,000 years after the Big Bang, the temperature of the Universe fell to the point where nuclei could combine with electrons to create neutral atoms. As a result, photons no longer interacted frequently with matter and the universe became transparent. The highly redshifted photons from this period form the cosmic microwave background. Tiny variations in temperature and density detectable in the CMB were the early "seeds" from which all subsequent structure formation took place.

Cosmological models

Model of the universe based on general relativity

General relativity is the geometric theory of gravitation published by Albert Einstein in 1915 and the current description of gravitation in modern physics. It is the basis of current cosmological models of the universe. General relativity generalizes special relativity and Newton's law of universal gravitation, providing a unified description of gravity as a geometric property of space and time, or spacetime. In particular, the curvature of spacetime is directly related to the energy and momentum of whatever matter and radiation are present. The relation is specified by the Einstein field equations, a system of partial differential equations. In general relativity, the distribution of matter and energy determines the geometry of spacetime, which in turn describes the acceleration of matter. Therefore, solutions of the Einstein field equations describe the evolution of the universe. Combined with measurements of the amount, type, and distribution of matter in the universe, the equations of general relativity describe the evolution of the universe over time.

With the assumption of the cosmological principle that the universe is homogeneous and isotropic everywhere, a specific solution of the field equations that describes the universe is the metric tensor called the Friedmann–Lemaître–Robertson–Walker metric,

where (r, θ, φ) correspond to a spherical coordinate system. This metric has only two undetermined parameters. An overall dimensionless length scale factor R describes the size scale of the universe as a function of time; an increase in R is the expansion of the universe. A curvature index k describes the geometry. The index k is defined so that it can take only one of three values: 0, corresponding to flat Euclidean geometry; 1, corresponding to a space of positive curvature; or −1, corresponding to a space of positive or negative curvature. The value of R as a function of time t depends upon k and the cosmological constant Λ. The cosmological constant represents the energy density of the vacuum of space and could be related to dark energy. The equation describing how R varies with time is known as the Friedmann equation after its inventor, Alexander Friedmann.

The solutions for R(t) depend on k and Λ, but some qualitative features of such solutions are general. First and most importantly, the length scale R of the universe can remain constant only if the universe is perfectly isotropic with positive curvature (k=1) and has one precise value of density everywhere, as first noted by Albert Einstein. However, this equilibrium is unstable: because the universe is inhomogeneous on smaller scales, R must change over time. When R changes, all the spatial distances in the universe change in tandem; there is an overall expansion or contraction of space itself. This accounts for the observation that galaxies appear to be flying apart; the space between them is stretching. The stretching of space also accounts for the apparent paradox that two galaxies can be 40 billion light-years apart, although they started from the same point 13.8 billion years ago and never moved faster than the speed of light.

Second, all solutions suggest that there was a gravitational singularity in the past, when R went to zero and matter and energy were infinitely dense. It may seem that this conclusion is uncertain because it is based on the questionable assumptions of perfect homogeneity and isotropy (the cosmological principle) and that only the gravitational interaction is significant. However, the Penrose–Hawking singularity theorems show that a singularity should exist for very general conditions. Hence, according to Einstein's field equations, R grew rapidly from an unimaginably hot, dense state that existed immediately following this singularity (when R had a small, finite value); this is the essence of the Big Bang model of the universe. Understanding the singularity of the Big Bang likely requires a quantum theory of gravity, which has not yet been formulated.

Third, the curvature index k determines the sign of the mean spatial curvature of spacetime averaged over sufficiently large length scales (greater than about a billion light-years). If k=1, the curvature is positive and the universe has a finite volume. A universe with positive curvature is often visualized as a three-dimensional sphere embedded in a four-dimensional space. Conversely, if k is zero or negative, the universe has an infinite volume. It may seem counter-intuitive that an infinite and yet infinitely dense universe could be created in a single instant at the Big Bang when R=0, but exactly that is predicted mathematically when k does not equal 1. By analogy, an infinite plane has zero curvature but infinite area, whereas an infinite cylinder is finite in one direction and a torus is finite in both. A toroidal universe could behave like a normal universe with periodic boundary conditions.

The ultimate fate of the universe is still unknown because it depends critically on the curvature index k and the cosmological constant Λ. If the universe were sufficiently dense, k would equal +1, meaning that its average curvature throughout is positive and the universe will eventually recollapse in a Big Crunch, possibly starting a new universe in a Big Bounce. Conversely, if the universe were insufficiently dense, k would equal 0 or −1 and the universe would expand forever, cooling off and eventually reaching the Big Freeze and the heat death of the universe. Modern data suggests that the rate of expansion of the universe is not decreasing, as originally expected, but increasing; if this continues indefinitely, the universe may eventually reach a Big Rip. Observationally, the universe appears to be flat (k = 0), with an overall density that is very close to the critical value between recollapse and eternal expansion.

Multiverse hypothesis

Some speculative theories have proposed that our universe is but one of a set of disconnected universes, collectively denoted as the multiverse, challenging or enhancing more limited definitions of the universe. Scientific multiverse models are distinct from concepts such as alternate planes of consciousness and simulated reality.

Max Tegmark developed a four-part classification scheme for the different types of multiverses that scientists have suggested in response to various Physics problems. An example of such multiverses is the one resulting from the chaotic inflation model of the early universe. Another is the multiverse resulting from the many-worlds interpretation of quantum mechanics. In this interpretation, parallel worlds are generated in a manner similar to quantum superposition and decoherence, with all states of the wave functions being realized in separate worlds. Effectively, in the many-worlds interpretation the multiverse evolves as a universal wavefunction. If the Big Bang that created our multiverse created an ensemble of multiverses, the wave function of the ensemble would be entangled in this sense.

The least controversial, but still highly disputed, category of multiverse in Tegmark's scheme is Level I. The multiverses of this level are composed by distant spacetime events "in our own universe". Tegmark and others have argued that, if space is infinite, or sufficiently large and uniform, identical instances of the history of Earth's entire Hubble volume occur every so often, simply by chance. Tegmark calculated that our nearest so-called doppelgänger, is 1010115 metres away from us (a double exponential function larger than a googolplex). However, the arguments used are of speculative nature. Additionally, it would be impossible to scientifically verify the existence of an identical Hubble volume.

It is possible to conceive of disconnected spacetimes, each existing but unable to interact with one another. An easily visualized metaphor of this concept is a group of separate soap bubbles, in which observers living on one soap bubble cannot interact with those on other soap bubbles, even in principle. According to one common terminology, each "soap bubble" of spacetime is denoted as a universe, whereas our particular spacetime is denoted as the universe, just as we call our moon the Moon. The entire collection of these separate spacetimes is denoted as the multiverse. With this terminology, different universes are not causally connected to each other. In principle, the other unconnected universes may have different dimensionalities and topologies of spacetime, different forms of matter and energy, and different physical laws and physical constants, although such possibilities are purely speculative. Others consider each of several bubbles created as part of chaotic inflation to be separate universes, though in this model these universes all share a causal origin.

Historical conceptions

Historically, there have been many ideas of the cosmos (cosmologies) and its origin (cosmogonies). Theories of an impersonal universe governed by physical laws were first proposed by the Greeks and Indians. Ancient Chinese philosophy encompassed the notion of the universe including both all of space and all of time. Over the centuries, improvements in astronomical observations and theories of motion and gravitation led to ever more accurate descriptions of the universe. The modern era of cosmology began with Albert Einstein's 1915 general theory of relativity, which made it possible to quantitatively predict the origin, evolution, and conclusion of the universe as a whole. Most modern, accepted theories of cosmology are based on general relativity and, more specifically, the predicted Big Bang.

Mythologies

Many cultures have stories describing the origin of the world and universe. Cultures generally regard these stories as having some truth. There are however many differing beliefs in how these stories apply amongst those believing in a supernatural origin, ranging from a god directly creating the universe as it is now to a god just setting the "wheels in motion" (for example via mechanisms such as the big bang and evolution).

Ethnologists and anthropologists who study myths have developed various classification schemes for the various themes that appear in creation stories. For example, in one type of story, the world is born from a world egg; such stories include the Finnish epic poem Kalevala, the Chinese story of Pangu or the Indian Brahmanda Purana. In related stories, the universe is created by a single entity emanating or producing something by him- or herself, as in the Tibetan Buddhism concept of Adi-Buddha, the ancient Greek story of Gaia (Mother Earth), the Aztec goddess Coatlicue myth, the ancient Egyptian god Atum story, and the Judeo-Christian Genesis creation narrative in which the Abrahamic God created the universe. In another type of story, the universe is created from the union of male and female deities, as in the Maori story of Rangi and Papa. In other stories, the universe is created by crafting it from pre-existing materials, such as the corpse of a dead god—as from Tiamat in the Babylonian epic Enuma Elish or from the giant Ymir in Norse mythology—or from chaotic materials, as in Izanagi and Izanami in Japanese mythology. In other stories, the universe emanates from fundamental principles, such as Brahman and Prakrti, the creation myth of the Serers, or the yin and yang of the Tao.

Philosophical models

The pre-Socratic Greek philosophers and Indian philosophers developed some of the earliest philosophical concepts of the universe. The earliest Greek philosophers noted that appearances can be deceiving, and sought to understand the underlying reality behind the appearances. In particular, they noted the ability of matter to change forms (e.g., ice to water to steam) and several philosophers proposed that all the physical materials in the world are different forms of a single primordial material, or arche. The first to do so was Thales, who proposed this material to be water. Thales' student, Anaximander, proposed that everything came from the limitless apeiron. Anaximenes proposed the primordial material to be air on account of its perceived attractive and repulsive qualities that cause the arche to condense or dissociate into different forms. Anaxagoras proposed the principle of Nous (Mind), while Heraclitus proposed fire (and spoke of logos). Empedocles proposed the elements to be earth, water, air and fire. His four-element model became very popular. Like Pythagoras, Plato believed that all things were composed of number, with Empedocles' elements taking the form of the Platonic solids. Democritus, and later philosophers—most notably Leucippus—proposed that the universe is composed of indivisible atoms moving through a void (vacuum), although Aristotle did not believe that to be feasible because air, like water, offers resistance to motion. Air will immediately rush in to fill a void, and moreover, without resistance, it would do so indefinitely fast.

Although Heraclitus argued for eternal change, his contemporary Parmenides made the radical suggestion that all change is an illusion, that the true underlying reality is eternally unchanging and of a single nature. Parmenides denoted this reality as τὸ ἐν (The One). Parmenides' idea seemed implausible to many Greeks, but his student Zeno of Elea challenged them with several famous paradoxes. Aristotle responded to these paradoxes by developing the notion of a potential countable infinity, as well as the infinitely divisible continuum. Unlike the eternal and unchanging cycles of time, he believed that the world is bounded by the celestial spheres and that cumulative stellar magnitude is only finitely multiplicative.

The Indian philosopher Kanada, founder of the Vaisheshika school, developed a notion of atomism and proposed that light and heat were varieties of the same substance. In the 5th century AD, the Buddhist atomist philosopher Dignāga proposed atoms to be point-sized, durationless, and made of energy. They denied the existence of substantial matter and proposed that movement consisted of momentary flashes of a stream of energy.

The notion of temporal finitism was inspired by the doctrine of creation shared by the three Abrahamic religions: Judaism, Christianity and Islam. The Christian philosopher, John Philoponus, presented the philosophical arguments against the ancient Greek notion of an infinite past and future. Philoponus' arguments against an infinite past were used by the early Muslim philosopher, Al-Kindi (Alkindus); the Jewish philosopher, Saadia Gaon (Saadia ben Joseph); and the Muslim theologian, Al-Ghazali (Algazel).

Astronomical concepts

Astronomical models of the universe were proposed soon after astronomy began with the Babylonian astronomers, who viewed the universe as a flat disk floating in the ocean, and this forms the premise for early Greek maps like those of Anaximander and Hecataeus of Miletus.

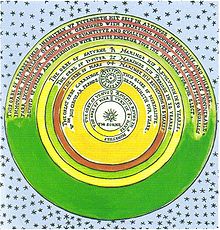

Later Greek philosophers, observing the motions of the heavenly bodies, were concerned with developing models of the universe-based more profoundly on empirical evidence. The first coherent model was proposed by Eudoxus of Cnidos. According to Aristotle's physical interpretation of the model, celestial spheres eternally rotate with uniform motion around a stationary Earth. Normal matter is entirely contained within the terrestrial sphere.

De Mundo (composed before 250 BC or between 350 and 200 BC), stated, "Five elements, situated in spheres in five regions, the less being in each case surrounded by the greater—namely, earth surrounded by water, water by air, air by fire, and fire by ether—make up the whole universe".

This model was also refined by Callippus and after concentric spheres were abandoned, it was brought into nearly perfect agreement with astronomical observations by Ptolemy. The success of such a model is largely due to the mathematical fact that any function (such as the position of a planet) can be decomposed into a set of circular functions (the Fourier modes). Other Greek scientists, such as the Pythagorean philosopher Philolaus, postulated (according to Stobaeus account) that at the center of the universe was a "central fire" around which the Earth, Sun, Moon and planets revolved in uniform circular motion.

The Greek astronomer Aristarchus of Samos was the first known individual to propose a heliocentric model of the universe. Though the original text has been lost, a reference in Archimedes' book The Sand Reckoner describes Aristarchus's heliocentric model. Archimedes wrote:

You, King Gelon, are aware the universe is the name given by most astronomers to the sphere the center of which is the center of the Earth, while its radius is equal to the straight line between the center of the Sun and the center of the Earth. This is the common account as you have heard from astronomers. But Aristarchus has brought out a book consisting of certain hypotheses, wherein it appears, as a consequence of the assumptions made, that the universe is many times greater than the universe just mentioned. His hypotheses are that the fixed stars and the Sun remain unmoved, that the Earth revolves about the Sun on the circumference of a circle, the Sun lying in the middle of the orbit, and that the sphere of fixed stars, situated about the same center as the Sun, is so great that the circle in which he supposes the Earth to revolve bears such a proportion to the distance of the fixed stars as the center of the sphere bears to its surface.

Aristarchus thus believed the stars to be very far away, and saw this as the reason why stellar parallax had not been observed, that is, the stars had not been observed to move relative each other as the Earth moved around the Sun. The stars are in fact much farther away than the distance that was generally assumed in ancient times, which is why stellar parallax is only detectable with precision instruments. The geocentric model, consistent with planetary parallax, was assumed to be an explanation for the unobservability of the parallel phenomenon, stellar parallax. The rejection of the heliocentric view was apparently quite strong, as the following passage from Plutarch suggests (On the Apparent Face in the Orb of the Moon):

Cleanthes [a contemporary of Aristarchus and head of the Stoics] thought it was the duty of the Greeks to indict Aristarchus of Samos on the charge of impiety for putting in motion the Hearth of the Universe [i.e. the Earth], ... supposing the heaven to remain at rest and the Earth to revolve in an oblique circle, while it rotates, at the same time, about its own axis.

The only other astronomer from antiquity known by name who supported Aristarchus's heliocentric model was Seleucus of Seleucia, a Hellenistic astronomer who lived a century after Aristarchus. According to Plutarch, Seleucus was the first to prove the heliocentric system through reasoning, but it is not known what arguments he used. Seleucus' arguments for a heliocentric cosmology were probably related to the phenomenon of tides. According to Strabo (1.1.9), Seleucus was the first to state that the tides are due to the attraction of the Moon, and that the height of the tides depends on the Moon's position relative to the Sun. Alternatively, he may have proved heliocentricity by determining the constants of a geometric model for it, and by developing methods to compute planetary positions using this model, like what Nicolaus Copernicus later did in the 16th century. During the Middle Ages, heliocentric models were also proposed by the Indian astronomer Aryabhata, and by the Persian astronomers Albumasar and Al-Sijzi.

The Aristotelian model was accepted in the Western world for roughly two millennia, until Copernicus revived Aristarchus's perspective that the astronomical data could be explained more plausibly if the Earth rotated on its axis and if the Sun were placed at the center of the universe.

In the center rests the Sun. For who would place this lamp of a very beautiful temple in another or better place than this wherefrom it can illuminate everything at the same time?

— Nicolaus Copernicus, in Chapter 10, Book 1 of De Revolutionibus Orbium Coelestrum (1543)

As noted by Copernicus himself, the notion that the Earth rotates is very old, dating at least to Philolaus (c. 450 BC), Heraclides Ponticus (c. 350 BC) and Ecphantus the Pythagorean. Roughly a century before Copernicus, the Christian scholar Nicholas of Cusa also proposed that the Earth rotates on its axis in his book, On Learned Ignorance (1440). Al-Sijzi also proposed that the Earth rotates on its axis. Empirical evidence for the Earth's rotation on its axis, using the phenomenon of comets, was given by Tusi (1201–1274) and Ali Qushji (1403–1474).

This cosmology was accepted by Isaac Newton, Christiaan Huygens and later scientists. Edmund Halley (1720) and Jean-Philippe de Chéseaux (1744) noted independently that the assumption of an infinite space filled uniformly with stars would lead to the prediction that the nighttime sky would be as bright as the Sun itself; this became known as Olbers' paradox in the 19th century. Newton believed that an infinite space uniformly filled with matter would cause infinite forces and instabilities causing the matter to be crushed inwards under its own gravity. This instability was clarified in 1902 by the Jeans instability criterion. One solution to these paradoxes is the Charlier Universe, in which the matter is arranged hierarchically (systems of orbiting bodies that are themselves orbiting in a larger system, ad infinitum) in a fractal way such that the universe has a negligibly small overall density; such a cosmological model had also been proposed earlier in 1761 by Johann Heinrich Lambert. A significant astronomical advance of the 18th century was the realization by Thomas Wright, Immanuel Kant and others of nebulae.

In 1919, when the Hooker Telescope was completed, the prevailing view still was that the universe consisted entirely of the Milky Way Galaxy. Using the Hooker Telescope, Edwin Hubble identified Cepheid variables in several spiral nebulae and in 1922–1923 proved conclusively that Andromeda Nebula and Triangulum among others, were entire galaxies outside our own, thus proving that universe consists of a multitude of galaxies.

The modern era of physical cosmology began in 1917, when Albert Einstein first applied his general theory of relativity to model the structure and dynamics of the universe.