From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

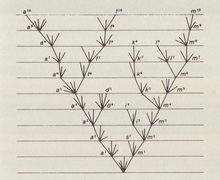

In Late Devonian vertebrate speciation, descendants of pelagic lobe-finned fish — like Eusthenopteron — exhibited a sequence of adaptations: *Panderichthys, suited to muddy shallows *Tiktaalik with limb-like fins that could take it onto land *Early tetrapods in weed-filled swamps, such as: **Acanthostega, which had feet with eight digits **Ichthyostega with limbs Descendants also included pelagic lobe-finned fish such as coelacanth species.

The evolution of tetrapods began about 395 million years ago in the Devonian Period with the earliest tetrapods derived from the lobe-finned fishes.[1] Tetrapods are categorized as a biological superclass, Tetrapoda, which includes all living and extinct amphibians, reptiles, birds, and mammals. While most species today are terrestrial, little evidence supports the idea that any of the earliest tetrapods could move about on land, as their limbs could not have held their midsections off the ground and the known trackways do not indicate they dragged their bellies around. Presumably, the tracks were made by animals walking along the bottoms of shallow bodies of water.[2] The specific aquatic ancestors of the tetrapods, and the process by which land colonization occurred, remain unclear, and are areas of active research and debate among palaeontologists at present.

Amphibians today generally remain semiaquatic, living the first stage of their lives as fish-like tadpoles. Several groups of tetrapods, such as the snakes and cetaceans, have lost some or all of their limbs. In addition, many tetrapods have returned to partially aquatic or fully aquatic lives throughout the history of the group (modern examples of fully aquatic tetrapods include cetaceans and sirenians). The first returns to an aquatic lifestyle may have occurred as early as the Carboniferous Period[3] whereas other returns occurred as recently as the Cenozoic, as in cetaceans, pinnipeds,[4] and several modern amphibians.[5]

The change from a body plan for breathing and navigating in water to a body plan enabling the animal to move on land is one of the most profound evolutionary changes known.[6] It is also one of the best understood, largely thanks to a number of significant transitional fossil finds in the late 20th century combined with improved phylogenetic analysis.[7]

Origin

Evolution of fish

The Devonian period is traditionally known as the "Age of Fish", marking the diversification of numerous extinct and modern major fish groups.[8] Among them were the early bony fishes, who diversified and spread in freshwater and brackish environments at the beginning of the period. The early types resembled their cartilaginous ancestors in many features of their anatomy, including a shark-like tailfin, spiral gut, large pectoral fins stiffened in front by skeletal elements and a largely unossified axial skeleton.[9]They did, however, have certain traits separating them from cartilaginous fishes, traits that would become pivotal in the evolution of terrestrial forms. With the exception of a pair of spiracles, the gills did not open singly to the exterior as they do in sharks; rather, they were encased in a gill chamber stiffened by membrane bones and covered by a bony operculum, with a single opening to the exterior. The cleithrum bone, forming the posterior margin of the gill chamber, also functioned as anchoring for the pectoral fins. The cartilaginous fishes do not have such an anchoring for the pectoral fins. This allowed for a movable joint at the base of the fins in the early bony fishes, and would later function in a weight bearing structure in tetrapods. As part of the overall armour of rhomboid cosmin scales, the skull had a full cover of dermal bone, constituting a skull roof over the otherwise shark-like cartilaginous inner cranium. Importantly, they also had a swim bladder/lung,[10] a feature lacking in sharks and rays.

Lungs before land

The lung/swim bladder originated as an outgrowth of the gut, forming a gas-filled bladder above the digestive system. In its primitive form, the air bladder was open to the alimentary canal, a condition called physostome and still found in many fish.[11] The primary function is not entirely certain. One consideration is buoyancy. The heavy scale armour of the early bony fishes would certainly weigh the animals down. In cartilaginous fishes, lacking a swim bladder, the open sea sharks need to swim constantly to avoid sinking into the depths, the pectoral fins providing lift.[12] Another factor is oxygen consumption. Ambient oxygen was relatively low in the early Devonian, possibly about half of modern values.[13] Per unit volume, there is much more oxygen in air than in water, and vertebrates are active animals with a high energy requirement compared to invertebrates of similar sizes.[14][15] The Devonian saw increasing oxygen levels which opened up new ecological niches by allowing groups able to exploit the additional oxygen to develop into active, large-bodied animals.[13] Particularly in tropical swampland habitats, atmospheric oxygen is much more stable, and may have prompted a reliance of lungs rather than gills for primary oxygen uptake.[16][17] In the end, both buoyancy and breathing may have been important, and some modern physostome fishes do indeed use their bladders for both.To function in gas exchange, lungs required a blood supply. In cartilaginous fishes and teleosts, the heart lies low in the body and pumps blood forward through the ventral aorta, which splits up in a series of paired aortic arches, each corresponding to a gill arch.[18] The aortic arches then merge above the gills to form a dorsal aorta supplying the body with oxygenated blood. In lungfishes, bowfin and bichirs, the swim bladder is supplied with blood by paired pulmonary arteries branching off from the hindmost (6th) aortic arch.[19] The same basic pattern is found in the lungfish Protopterus and in terrestrial salamanders, and was probably the pattern found in the tetrapods' immediate ancestors as well as the first tetrapods.[20] In most other bony fishes the swim bladder is supplied with blood by the dorsal aorta.[19]

External and internal nares

The nostrils in most bony fish differ from those of tetrapods. Normally, bony fish have four nares (nasal openings), one naris behind the other on each side. As the fish swims, water flows into the forward pair, across the olfactory tissue, and out through the posterior openings. This is true not only of ray-finned fish but also of the coelacanth, a fish included in the Sarcopterygii, the group that also includes the tetrapods. In contrast, the tetrapods have only one pair of nares externally but also sport a pair of internal nares, called choanae, allowing them to draw air through the nose. Lungfish are also sarcopterygians with internal nostrils, but these are sufficiently different from tetrapod choanae that they have long been recognized as an independent development.[21]The evolution of the tetrapods' internal nares was hotly debated in the 20th century. The internal nares could be one set of the external ones (usually presumed to be the posterior pair) that have migrated into the mouth, or the internal pair could be a newly evolved structure. To make way for a migration, however, the two tooth-bearing bones of the upper jaw, the maxilla and the premaxilla, would have to separate to let the nostril through and then rejoin; until recently, there was no evidence for a transitional stage, with the two bones disconnected. Such evidence is now available: a small lobe-finned fish called Kenichthys, found in China and dated at around 395 million years old, represents evolution "caught in mid-act", with the maxilla and premaxilla separated and an aperture—the incipient choana—on the lip in between the two bones.[22] Kenichthys is more closely related to tetrapods than is the coelacanth,[23] which has only external nares; it thus represents an intermediate stage in the evolution of the tetrapod condition. The reason for the evolutionary movement of the posterior nostril from the nose to lip, however, is not well understood.

Into the shallows

Devonian fishes, including an early shark Cladoselache, Eusthenopteron and other lobe-finned fishes, and the placoderm Bothriolepis (Joseph Smit, 1905).

The relatives of Kenichthys soon established themselves in the waterways and brackish estuaries and became the most numerous of the bony fishes throughout the Devonian and most of the Carboniferous. The basic anatomy of group is well known thanks to the very detailed work on Eusthenopteron by Erik Jarvik in the second half of the 20th century.[24] The bones of the skull roof were broadly similar to those of early tetrapods and the teeth had an infolding of the enamel similar to that of labyrinthodonts. The paired fins had a build with bones distinctly homologous to the humerus, ulna, and radius in the fore-fins and to the femur, tibia, and fibula in the pelvic fins.[25]

There were a number of families: Rhizodontida, Canowindridae, Elpistostegidae, Megalichthyidae, Osteolepidae and Tristichopteridae.[26] Most were open-water fishes, and some grew to very large sizes; adult specimens are several meters in length.[27] The Rhizodontid Rhizodus is estimated to have grown to 7 meters (23 feet), making it the largest freshwater fish known.[28]

While most of these were open-water fishes, one group, the Elpistostegalians, adapted to life in the shallows. They evolved flat bodies for movement in very shallow water, and the pectoral and pelvic fins took over as the main propulsion organs. Most median fins disappeared, leaving only a protocercal tailfin. Since the shallows were subject to occasional oxygen deficiency, the ability to breath atmospheric air with the swim bladder became increasingly important.[6] The spiracle became large and prominent, enabling these fishes to draw air.

Skull morphology

The tetrapods have their root in the early Devonian tetrapodomorph fish.[29] Primitive tetrapods developed from an osteolepid tetrapodomorph lobe-finned fish (sarcopterygian-crossopterygian), with a two-lobed brain in a flattened skull. The coelacanth group represents marine sarcopterygians that never acquired these shallow-water adaptations. The sarcopterygians apparently took two different lines of descent and are accordingly separated into two major groups: the Actinistia (including the coelacanths) and the Rhipidistia (which include extinct lines of lobe-finned fishes that evolved into the lungfish and the tetrapodomorphs).From fins to feet

The oldest known tetrapodomorph is Kenichthys from China, dated at around 395 million years old. Two of the earliest tetrapodomorphs, dating from 380 Ma, were Gogonasus and Panderichthys.[30]They had choanae and used their fins as to move through tidal channels and shallow waters choked with dead branches and rotting plants.[31] Their fins could have been used to attach themselves to plants or similar while they were lying in ambush for prey. The universal tetrapod characteristics of front limbs that bend forward from the elbow and hind limbs that bend backward from the knee can plausibly be traced to early tetrapods living in shallow water. Pelvic bone fossils from Tiktaalik shows, if representative for early tetrapods in general, that hind appendages and pelvic-propelled locomotion originated in water before terrestrial adaptations.[32]

Another indication that feet and other tetrapod traits evolved while the animals were still aquatic is how they were feeding. They did not have the modifications of the skull and jaw that allowed them to swallow prey on land. Prey could be caught in the shallows, at the water's edge or on land, but had to be eaten in water where hydrodynamic forces from the expansion of their buccal cavity would force the food into their esophagus.[33]

It has been suggested that the evolution of the tetrapod limb from fins in lobe-finned fishes is related to expression of the HOXD13 gene or the loss of the proteins actinodin 1 and actinodin 2, which are involved in fish fin development.[34][35] Robot simulations suggest that the necessary nervous circuitry for walking evolved from the nerves governing swimming, utilizing the sideways oscillation of the body with the limbs primarily functioning as anchoring points and providing limited thrust.[36]

A 2012 study using 3d reconstructions of Ichthyostega concluded that it was incapable of typical quadrupedal gaits. The limbs could not move alternately as they lacked the necessary rotary motion range. In addition, the hind limbs lacked the necessary pelvic musculature for hindlimb-driven land movement. Their most likely method of terrestrial locomotion is that of synchronous "crutching motions", similar to modern mudskippers.[37]

Denizens of the swamp

The first tetrapods probably evolved in coastal and brackish marine environments, and in shallow and swampy freshwater habitats.[38] Formerly, researchers thought the timing was towards the end of the Devonian. In 2010, this belief was challenged by the discovery of the oldest known tetrapod tracks, preserved in marine sediments of the southern coast of Laurasia, now Świętokrzyskie (Holy Cross) Mountains of Poland. They were made during the Eifelian stage at the end of the Middle Devonian.The tracks, some of which show digits, date to about 395 million years ago—18 million years earlier than the oldest known tetrapod body fossils.[39] Additionally, the tracks show that the animal was capable of thrusting its arms and legs forward, a type of motion that would have been impossible in tetrapodomorph fish like Tiktaalik. The animal that produced the tracks is estimated to have been up to 2.5 metres (8.2 ft) long with footpads up to 26 centimetres (10 in) wide, although most tracks are only 15 centimetres (5.9 in) wide.[40] The new finds suggest that the first tetrapods may have lived as opportunists on the tidal flats, feeding on marine animals that were washed up or stranded by the tide.[39] Currently, however, fish are stranded in significant numbers only at certain times of year, as in alewife spawning season; such strandings could not provide a significant supply of food for predators. There is no reason to suppose that Devonian fish were less prudent than those of today.[41] According to Melina Hale of University of Chicago, not all ancient trackways are necessarily made by early tetrapods, but could also be created by relatives of the tetrapods who used their fleshy appendages in a similar substrate-based locomotion.[42][43]

Palaeozoic tetrapods

Devonian tetrapods

Research by Jennifer A. Clack and her colleagues showed that the very earliest tetrapods, animals similar to Acanthostega, were wholly aquatic and quite unsuited to life on land. This is in contrast to the earlier view that fish had first invaded the land — either in search of prey (like modern mudskippers) or to find water when the pond they lived in dried out — and later evolved legs, lungs, etc.By the late Devonian, land plants had stabilized freshwater habitats, allowing the first wetland ecosystems to develop, with increasingly complex food webs that afforded new opportunities. Freshwater habitats were not the only places to find water filled with organic matter and choked with plants with dense vegetation near the water's edge. Swampy habitats like shallow wetlands, coastal lagoons and large brackish river deltas also existed at this time, and there is much to suggest that this is the kind of environment in which the tetrapods evolved. Early fossil tetrapods have been found in marine sediments, and because fossils of primitive tetrapods in general are found scattered all around the world, they must have spread by following the coastal lines — they could not have lived in freshwater only.

One analysis from the University of Oregon suggests no evidence for the "shrinking waterhole" theory - transitional fossils are not associated with evidence of shrinking puddles or ponds - and indicates that such animals would probably not have survived short treks between depleted waterholes.[44] The new theory suggests instead that proto-lungs and proto-limbs were useful adaptations to negotiate the environment in humid, wooded floodplains.[45]

The Devonian tetrapods went through two major bottlenecks during what is known as the Late Devonian extinction; one at the end of the Frasnian stage, and one twice as large at the end of the following Famennian stage. These events of extinctions led to the disappearance of primitive tetrapods with fish-like features like Ichthyostega and their primary more aquatic relatives.[46] When tetrapods reappear in the fossil record again after the Devonian extinctions, the adult forms are all fully adapted to a terrestrial existence, with later species secondary adapted to an aquatic lifestyle.[47]

Excretion in tetrapods

The common ancestor of all present gnathostomes lived in freshwater, and later migrated back to the sea. To deal with the much higher salinity in sea water, they evolved the ability to turn the nitrogen waste product ammonia into harmless urea, storing it in the body to give the blood the same osmolarity as the sea water without poisoning the organism. This is the system currently found in cartilaginous fishes. Ray-finned fishes (Actinopterygii) later returned to freshwater and lost this ability, while the fleshy-finned fishes (Sarcopterygii) retained it. Since the blood of ray-finned fishes contains more salt than freshwater, they could simply get rid of ammonia through their gills. When they finally returned to the sea again, they did not recover their old trick of turning ammonia to urea, and they had to evolve salt excreting glands instead. Lungfishes do the same when they are living in water, making ammonia and no urea, but when the water dries up and they are forced to burrow down in the mud, they switch to urea production. Like cartilaginous fishes, the coelacanth can store urea in its blood, as can the only known amphibians that can live for long periods of time in salt water (the toad Bufo marinus and the frog Rana cancrivora). These are traits they have inherited from their ancestors.If early tetrapods lived in freshwater, and if they lost the ability to produce urea and used ammonia only, they would have to evolve it from scratch again later. Not a single species of all the ray-finned fishes living today has been able to do that, so it is not likely the tetrapods would have done so either. Terrestrial animals that can only produce ammonia would have to drink constantly, making a life on land impossible (a few exceptions exist, as some terrestrial woodlice can excrete their nitrogenous waste as ammonia gas). This probably also was a problem at the start when the tetrapods started to spend time out of water, but eventually the urea system would dominate completely. Because of this it is not likely they emerged in freshwater (unless they first migrated into freshwater habitats and then migrated onto land so shortly after that they still retained the ability to make urea), although some species never left, or returned to, the water could of course have adapted to freshwater lakes and rivers.

Lungs

It is now clear that the common ancestor of the bony fishes (Osteichthyes) had a primitive air-breathing lung—later evolved into a swim bladder in most actinopterygians (ray-finned fishes). This suggests that crossopterygians evolved in warm shallow waters, using their simple lung when the oxygen level in the water became too low.Fleshy lobe-fins supported on bones rather than ray-stiffened fins seem to have been an ancestral trait of all bony fishes (Osteichthyes). The lobe-finned ancestors of the tetrapods evolved them further, while the ancestors of the ray-finned fishes (Actinopterygii) evolved their fins in a different direction. The most primitive group of actinopterygians, the bichirs, still have fleshy frontal fins.

Fossils of early tetrapods

Nine genera of Devonian tetrapods have been described, several known mainly or entirely from lower jaw material. All but one were from the Laurasian supercontinent, which comprised Europe, North America and Greenland. The only exception is a single Gondwanan genus, Metaxygnathus, which has been found in Australia.The first Devonian tetrapod identified from Asia was recognized from a fossil jawbone reported in 2002. The Chinese tetrapod Sinostega pani was discovered among fossilized tropical plants and lobe-finned fish in the red sandstone sediments of the Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region of northwest China. This finding substantially extended the geographical range of these animals and has raised new questions about the worldwide distribution and great taxonomic diversity they achieved within a relatively short time.

These earliest tetrapods were not terrestrial. The earliest confirmed terrestrial forms are known from the early Carboniferous deposits, some 20 million years later. Still, they may have spent very brief periods out of water and would have used their legs to paw their way through the mud.

Why they went to land in the first place is still debated. One reason could be that the small juveniles who had completed their metamorphosis had what it took to make use of what land had to offer. Already adapted to breathe air and move around in shallow waters near land as a protection (just as modern fish (and amphibians) often spent the first part of their life in the comparative safety of shallow waters like mangrove forests), two very different niches partially overlapped each other, with the young juveniles in the diffuse line between. One of them was overcrowded and dangerous while the other was much safer and much less crowded, offering less competition over resources. The terrestrial niche was also a much more challenging place for primary aquatic animals, but because of the way evolution and the selection pressure works, those juveniles who could take advantage of this would be rewarded. Once they gained a small foothold on land, thanks to their preadaptations and being at the right place at the right time, favourable variations in their descendants would gradually result in continuing evolution and diversification.

At this time the abundance of invertebrates crawling around on land and near water, in moist soil and wet litter, offered a food supply. Some were even big enough to eat small tetrapods, but the land was free from dangers common in the water.

From water to land

Initially making only tentative forays onto land, tetrapods adapted to terrestrial environments over time and spent longer periods away from the water. It is also possible that the adults started to spend some time on land (as the skeletal modifications in early tetrapods such as Ichthyostega suggests) to bask in the sun close to the water's edge, while otherwise being mostly aquatic.Carboniferous tetrapods

Until the 1990s, there was a 30 million year gap in the fossil record between the late Devonian tetrapods and the reappearance of tetrapod fossils in recognizable mid-Carboniferous amphibian lineages. It was referred to as "Romer's Gap", which now covers the period from about 360 to 345 million years ago (the Devonian-Carboniferous transition and the early Mississippian), after the palaeontologist who recognized it.During the "gap", tetrapod backbones developed, as did limbs with digits and other adaptations for terrestrial life. Ears, skulls and vertebral columns all underwent changes too. The number of digits on hands and feet became standardized at five, as lineages with more digits died out. The very few tetrapod fossils found in the "gap" are all the more precious.

The transition from an aquatic lobe-finned fish to an air-breathing amphibian was a momentous occasion in the evolutionary history of the vertebrates. For an animal to live in a gravity-neutral, aqueous environment and then invade one that is entirely different required major changes to the overall body plan, both in form and in function. Eryops is an example of an animal that made such adaptations. It retained and refined most of the traits found in its fish ancestors. Sturdy limbs supported and transported its body while out of water. A thicker, stronger backbone prevented its body from sagging under its own weight. Also, by utilizing vestigial fish jaw bones, a rudimentary ear was developed, allowing Eryops to hear airborne sound.

By the Visean age of mid-Carboniferous times the early tetrapods had radiated into at least three main branches. Recognizable basal-group tetrapods are representative of the temnospondyls (e.g. Eryops) lepospondyls (e.g. Diplocaulus) and anthracosaurs, which were the relatives and ancestors of the Amniota. Depending on whichever authorities one follows, modern amphibians (frogs, salamanders and caecilians) are derived from either temnospondyls or lepospondyls (or possibly both, although this is now a minority position).

The first amniotes are known from the early part of the Late Carboniferous, and during the Triassic counted among their number the earliest mammals, turtles, crocodiles (lizards and birds appeared in the Jurassic, and snakes in the Cretaceous), and a fourth Carboniferous group, the baphetids, which are thought related to temnospondyls, left no modern survivors.

Amphibians and reptiles were affected by the Carboniferous Rainforest Collapse (CRC), an extinction event that occurred ~300 million years ago. The sudden collapse of a vital ecosystem shifted the diversity and abundance of major groups. Several large groups, labyrinthodont amphibians were particularly devastated, while the first reptiles fared better, being ecologically adapted to the drier conditions that followed. Amphibians must return to water to lay eggs, in contrast, reptiles - whose amniote eggs have a membrane ensuring gas exchange out of water and can therefore be laid on land - were better adapted to the new conditions. Reptiles invaded new niches at a faster rate and began diversifying their diets, developing herbivory and carnivory, previously only having been insectivores and piscivores.[48]

Permian tetrapods

In the Permian period, in addition to temnospondyl and anthracosaur clades among the early "amphibia" (labyrinthodonts), there were two important clades of amniotes, the Sauropsida and the Synapsida. The latter were the most important and successful Permian animals.The end of the Permian saw a major turnover in fauna during the Permian–Triassic extinction event. There was a protracted loss of species, due to multiple extinction pulses.[49] Many of the once large and diverse groups died out or were greatly reduced.

Mesozoic tetrapods

Life on Earth seemed to recover quickly after the Permian extinctions, but this was mostly in the form of disaster taxa, such as the hardy Lystrosaurus; specialized animals that formed complex ecosystems, with high biodiversity, complex food webs and a variety of niches, took much longer to recover.[49] Current research indicates that this long recovery was due to successive waves of extinction, which inhibited recovery, and to prolonged environmental stress to organisms that continued into the Early Triassic. Recent research indicates that recovery did not begin until the start of the mid-Triassic, 4M to 6M years after the extinction;[50] and some writers estimate that the recovery was not complete until 30M years after the P-Tr extinction, i.e. in the late Triassic.[49]A small group of reptiles, the diapsids, began to diversify during the Triassic, notably the dinosaurs. By the late Mesozoic, the large labyrinthodont groups that first appeared during the Paleozoic such as temnospondyls and reptile-like amphibians had gone extinct. All current major groups of sauropsids evolved during the Mesozoic, with birds first appearing in the Jurassic as a derived clade of theropod dinosaurs. Many groups of synapsids such as anomodonts and therocephalians that once comprised the dominant terrestrial fauna of the Permian also became extinct during the Mesozoic; during the Triassic, however, one group (Cynodontia) gave rise to the descendant taxon Mammalia, which survived through the Mesozoic to later diversify during the Cenozoic.

Extant (living) tetrapods

Following the great faunal turnover at the end of the Mesozoic, only six major groups of tetrapods were left, all of which also include many extinct groups:- Lissamphibia: frogs and toads, newts and salamanders, and caecilians

- Testudines: turtles and tortoises

- Lepidosauria: tuataras, lizards, amphisbaenians and snakes

- Crocodilia: crocodiles, alligators, caimans and gharials

- Neornithes: modern birds

- Mammalia: mammals