| Latin | |

|---|---|

| Native to | |

| Ethnicity | |

| Era | As a native language, from the 7th century BC to c. AD 700 |

Early form | |

| Latin alphabet (Latin script) | |

| Official status | |

Official language in | |

| Regulated by | Pontifical Academy for Latin |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-1 | la |

| ISO 639-2 | lat |

| ISO 639-3 | lat |

| Glottolog | impe1234lati1261 |

| Linguasphere | 51-AAB-aa, -ab, -ac |

Greatest extent of the Roman Empire under Emperor Trajan (c. 117 AD) and the area governed by Latin speakers. Many languages other than Latin were spoken within the empire. | |

Latin (lingua Latina, Latin: [ˈlɪŋɡʷa ɫaˈtiːna], or Latinum, Latin: [ɫaˈtiːnʊ̃]) is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Considered a dead language, Latin was originally spoken in Latium (now known as Lazio), the lower Tiber area around Rome. Through the expansion of the Roman Republic it became the dominant language in the Italian Peninsula and subsequently throughout the Roman Empire. Even after the fall of Western Rome, Latin remained the common language of international communication, science, scholarship and academia in Europe until well into the early 19th century, when regional vernaculars supplanted it in common academic and political usage—including its own descendants, the Romance languages. For most of the time it was used, it would be considered a dead language in the modern linguistic definition; that is, it lacked native speakers, despite being used extensively and actively.

Latin grammar is highly fusional, with classes of inflections for case, number, person, gender, tense, mood, voice, and aspect. The Latin alphabet is directly derived from the Etruscan and Greek alphabets.

By the late Roman Republic (75 BC), Old Latin had evolved into standardized Classical Latin. Vulgar Latin was the colloquial register with less prestigious variations attested in inscriptions and some literary works such as those of the comic playwrights Plautus and Terence and the author Petronius. Late Latin is the literary language from the 3rd century AD onward, and Vulgar Latin's various regional dialects had developed by the 6th to 9th centuries into the ancestors of the modern Romance languages.

In Latin's usage beyond the early medieval period, it lacked native speakers. Medieval Latin was used across Western and Catholic Europe during the Middle Ages as a working and literary language from the 9th century to the Renaissance, which then developed a classicizing form, called Renaissance Latin. This was the basis for Neo-Latin which evolved during the early modern period. In these periods Latin was used productively and generally taught to be written and spoken, at least until the late seventeenth century, when spoken skills began to erode. It then became increasingly taught only to be read.

Latin remains the official language of the Holy See and the Roman Rite of the Catholic Church at the Vatican City. The church continues to adapt concepts from modern languages to Ecclesiastical Latin of the Latin language. Contemporary Latin is more often studied to be read rather than spoken or actively used.

Latin has greatly influenced the English language, along with a large amount of others, and historically contributed many words to the English lexicon, particularly after the Christianization of the Anglo-Saxons and the Norman Conquest. Latin and Ancient Greek roots are heavily used in English vocabulary in theology, the sciences, medicine, and law.

History

A number of phases of the language have been recognized, each distinguished by subtle differences in vocabulary, usage, spelling, and syntax. There are no hard and fast rules of classification; different scholars emphasize different features. As a result, the list has variants, as well as alternative names.

In addition to the historical phases, Ecclesiastical Latin refers to the styles used by the writers of the Roman Catholic Church from late antiquity onward, as well as by Protestant scholars.

After the Western Roman Empire fell in 476 and Germanic kingdoms took its place, the Germanic people adopted Latin as a language more suitable for legal and other, more formal uses.

Old Latin

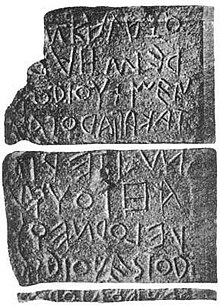

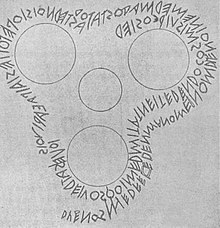

The earliest known form of Latin is Old Latin, also called Archaic or Early Latin, which was spoken from the Roman Kingdom, traditionally founded in 753 BC, through the later part of the Roman Republic, up to 75 BC, i.e. before the age of Classical Latin. It is attested both in inscriptions and in some of the earliest extant Latin literary works, such as the comedies of Plautus and Terence. The Latin alphabet was devised from the Etruscan alphabet. The writing later changed from what was initially either a right-to-left or a boustrophedon script to what ultimately became a strictly left-to-right script.

Classical Latin

During the late republic and into the first years of the empire, from about 75 BC to 200 AD, a new Classical Latin arose, a conscious creation of the orators, poets, historians and other literate men, who wrote the great works of classical literature, which were taught in grammar and rhetoric schools. Today's instructional grammars trace their roots to such schools, which served as a sort of informal language academy dedicated to maintaining and perpetuating educated speech.

Vulgar Latin

Philological analysis of Archaic Latin works, such as those of Plautus, which contain fragments of everyday speech, gives evidence of an informal register of the language, Vulgar Latin (termed sermo vulgi, "the speech of the masses", by Cicero). Some linguists, particularly in the nineteenth century, believed this to be a separate language, existing more or less in parallel with the literary or educated Latin, but this is now widely dismissed.

The term 'Vulgar Latin' remains difficult to define, referring both to informal speech at any time within the history of Latin, and the kind of informal Latin that had begun to move away from the written language significantly in the post-Imperial period, that led ultimately to the Romance languages.

During the Classical period, informal language was rarely written, so philologists have been left with only individual words and phrases cited by classical authors, inscriptions such as Curse tablets and those found as graffiti. In the Late Latin period, language changes reflecting spoken (non-classical) norms tend to be found in greater quantities in texts. As it was free to develop on its own, there is no reason to suppose that the speech was uniform either diachronically or geographically. On the contrary, Romanised European populations developed their own dialects of the language, which eventually led to the differentiation of Romance languages.

Late Latin

Late Latin is a kind of written Latin used in the 3rd to 6th centuries. This began to diverge from Classical forms at a faster pace. It is characterised by greater use of prepositions, and word order that is closer to modern Romance languages, for example, while grammatically retaining more or less the same formal rules as Classical Latin.

Ultimately, Latin diverged into a distinct written form, where the commonly spoken form was perceived as a separate language, for instance early French or Italian dialects, that could be transcribed differently. It took some time for these to be viewed as wholly different from Latin however.

Romance languages

While the written form of Latin was increasingly standardized into a fixed form, the spoken forms began to diverge more greatly. Currently, the five most widely spoken Romance languages by number of native speakers are Spanish, Portuguese, French, Italian, and Romanian. Despite dialectal variation, which is found in any widespread language, the languages of Spain, France, Portugal, and Italy have retained a remarkable unity in phonological forms and developments, bolstered by the stabilising influence of their common Christian (Roman Catholic) culture.

It was not until the Muslim conquest of Spain in 711, cutting off communications between the major Romance regions, that the languages began to diverge seriously. The spoken Latin that would later become Romanian diverged somewhat more from the other varieties, as it was largely separated from the unifying influences in the western part of the Empire.

Spoken Latin began to diverge into distinct languages by the 9th century at the latest, when the earliest extant Romance writings begin to appear. They were, throughout the period, confined to everyday speech, as Medieval Latin was used for writing.

It should also be noted, however, that for many Italians using Latin, there was no complete separation between Italian and Latin, even into the beginning of the Renaissance. Petrarch for example saw Latin as a literary version of the spoken language.

Medieval Latin

Medieval Latin is the written Latin in use during that portion of the postclassical period when no corresponding Latin vernacular existed, that is from around 700 to 1500 AD. The spoken language had developed into the various Romance languages; however, in the educated and official world, Latin continued without its natural spoken base. Moreover, this Latin spread into lands that had never spoken Latin, such as the Germanic and Slavic nations. It became useful for international communication between the member states of the Holy Roman Empire and its allies.

Without the institutions of the Roman Empire that had supported its uniformity, Medieval Latin was much freer in its linguistic cohesion: for example, in classical Latin sum and eram are used as auxiliary verbs in the perfect and pluperfect passive, which are compound tenses. Medieval Latin might use fui and fueram instead. Furthermore, the meanings of many words were changed and new words were introduced, often under influence from the vernacular. Identifiable individual styles of classically incorrect Latin prevail.

Renaissance and Neo-Latin

Renaissance Latin, 1300 to 1500, and the classicised Latin that followed through to the present are often grouped together as Neo-Latin, or New Latin, which have in recent decades become a focus of renewed study, given their importance for the development of European culture, religion and science. The vast majority of written Latin belongs to this period, but its full extent is unknown.

The Renaissance reinforced the position of Latin as a spoken and written language by the scholarship by the Renaissance humanists. Petrarch and others began to change their usage of Latin as they explored the texts of the Classical Latin world. Skills of textual criticism evolved to create much more accurate versions of extant texts through the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, and some important texts were rediscovered. Comprehensive versions of author's works were published by Isaac Casaubon, Joseph Scaliger and others. Nevertheless, despite the careful work of Petrarch, Politian and others, first the demand for manuscripts, and then the rush to bring works into print, led to the circulation of inaccurate copies for several centuries following.

Neo-Latin literature was extensive and prolific, but less well known or understood today. Works covered poetry, prose stories and early novels, occasional pieces and collections of letters, to name a few. Famous and well regarded writers included Petrarch, Erasmus, Salutati, Celtis, George Buchanan and Thomas More. Non fiction works were long produced in many subjects, including the sciences, law, philosophy, historiography and theology. Famous examples include Isaac Newton's Principia. Latin was also used as a convenient medium for translations of important works first written in a vernacular, such as those of Descartes.

Latin education underwent a process of reform to classicise written and spoken Latin. Schooling remained largely Latin medium until approximately 1700. Until the end of the 17th century, the majority of books and almost all diplomatic documents were written in Latin. Afterwards, most diplomatic documents were written in French (a Romance language) and later native or other languages. Education methods gradually shifted towards written Latin, and eventually concentrating solely on reading skills. The decline of Latin education took several centuries and proceeded much more slowly than the decline in written Latin output.

Contemporary Latin

Despite having no native speakers, Latin is still used for a variety of purposes in the contemporary world.

Religious use

The largest organisation that retains Latin in official and quasi-official contexts is the Catholic Church. The Catholic Church required that Mass be carried out in Latin until the Second Vatican Council of 1962–1965, which permitted the use of the vernacular. Latin remains the language of the Roman Rite. The Tridentine Mass (also known as the Extraordinary Form or Traditional Latin Mass) is celebrated in Latin. Although the Mass of Paul VI (also known as the Ordinary Form or the Novus Ordo) is usually celebrated in the local vernacular language, it can be and often is said in Latin, in part or in whole, especially at multilingual gatherings. It is the official language of the Holy See, the primary language of its public journal, the Acta Apostolicae Sedis, and the working language of the Roman Rota. Vatican City is also home to the world's only automatic teller machine that gives instructions in Latin. In the pontifical universities postgraduate courses of Canon law are taught in Latin, and papers are written in the same language.

There are a small number of Latin services held in the Anglican church. These include an annual service in Oxford, delivered with a Latin sermon; a relic from the period when Latin was the normal spoken language of the university.

Use of Latin for mottos

In the Western world, many organizations, governments and schools use Latin for their mottos due to its association with formality, tradition, and the roots of Western culture.

Canada's motto A mari usque ad mare ("from sea to sea") and most provincial mottos are also in Latin. The Canadian Victoria Cross is modelled after the British Victoria Cross which has the inscription "For Valour". Because Canada is officially bilingual, the Canadian medal has replaced the English inscription with the Latin Pro Valore.

Spain's motto Plus ultra, meaning "even further", or figuratively "Further!", is also Latin in origin. It is taken from the personal motto of Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor and King of Spain (as Charles I), and is a reversal of the original phrase Non terrae plus ultra ("No land further beyond", "No further!"). According to legend, this phrase was inscribed as a warning on the Pillars of Hercules, the rocks on both sides of the Strait of Gibraltar and the western end of the known, Mediterranean world. Charles adopted the motto following the discovery of the New World by Columbus, and it also has metaphorical suggestions of taking risks and striving for excellence.

In the United States the unofficial national motto until 1956 was E pluribus unum meaning "Out of many, one". The motto continues to be featured on the Great Seal, it also appears on the flags and seals of both houses of congress and the flags of the states of Michigan, North Dakota, New York, and Wisconsin. The motto's 13 letters symbolically represent the original Thirteen Colonies which revolted from the British Crown. The motto is featured on all presently minted coinage and has been featured in most coinage throughout the nation's history.

Several states of the United States have Latin mottos, such as:

- Arizona's Ditat deus ("God enriches");

- Connecticut's Qui transtulit sustinet ("He who transplanted sustains");

- Kansas's Ad astra per aspera ("Through hardships, to the stars");

- Colorado's Nil sine numine ("Nothing without providence");

- Michigan's Si quaeris peninsulam amoenam, circumspice ("If you seek a pleasant peninsula, look about you"), is based on that of Sir Christopher Wren, in St. Paul's Cathedral;

- Missouri's Salus populi suprema lex esto ("The health of the people should be the highest law");

- New York (state)'s Excelsior ("Ever upward");

- North Carolina's Esse Quam Videri ("To be rather than to seem");

- South Carolina's Dum spiro spero ("While [still] breathing, I hope");

- Virginia's Sic semper tyrannis ("Thus always to tyrants"); and

- West Virginia's Montani Semper Liberi ("Mountaineers [are] always free").

Many military organizations today have Latin mottos, such as:

- Semper Paratus ("always ready"), the motto of the United States Coast Guard;

- Semper Fidelis ("always faithful"), the motto of the United States Marine Corps;

- Semper Supra ("always above"), the motto of the United States Space Force;

- Per ardua ad astra ("Through adversity/struggle to the stars"), the motto of the Royal Air Force (RAF); and

- Vigilamus pro te ("We stand on guard for thee"), the motto of the Canadian Armed Forces.

A law governing body in the Philippines have a Latin motto, such as:

- Justitiae Pax Opus ("Justice, peace, work"), the motto of the Department of Justice (Philippines);

Some colleges and universities have adopted Latin mottos, for example Harvard University's motto is Veritas ("truth"). Veritas was the goddess of truth, a daughter of Saturn, and the mother of Virtue.

Other modern uses

Switzerland has adopted the country's Latin short name Helvetia on coins and stamps, since there is no room to use all of the nation's four official languages. For a similar reason, it adopted the international vehicle and internet code CH, which stands for Confoederatio Helvetica, the country's full Latin name.

Some film and television in ancient settings, such as Sebastiane, The Passion of the Christ and Barbarians (2020 TV series), have been made with dialogue in Latin. Occasionally, Latin dialogue is used because of its association with religion or philosophy, in such film/television series as The Exorcist and Lost ("Jughead"). Subtitles are usually shown for the benefit of those who do not understand Latin. There are also songs written with Latin lyrics. The libretto for the opera-oratorio Oedipus rex by Igor Stravinsky is in Latin.

The continued instruction of Latin is often seen as a highly valuable component of a liberal arts education. Latin is taught at many high schools, especially in Europe and the Americas. It is most common in British public schools and grammar schools, the Italian liceo classico and liceo scientifico, the German Humanistisches Gymnasium and the Dutch gymnasium.

Occasionally, some media outlets, targeting enthusiasts, broadcast in Latin. Notable examples include Radio Bremen in Germany, YLE radio in Finland (the Nuntii Latini broadcast from 1989 until it was shut down in June 2019), and Vatican Radio & Television, all of which broadcast news segments and other material in Latin.

A variety of organisations, as well as informal Latin 'circuli' ('circles'), have been founded in more recent times to support the use of spoken Latin. Moreover, a number of university classics departments have begun incorporating communicative pedagogies in their Latin courses. These include the University of Kentucky, the University of Oxford and also Princeton University.

There are many websites and forums maintained in Latin by enthusiasts. The Latin Wikipedia has more than 130,000 articles.

Urdaneta City's motto Deo servire populo sufficere ("It is enough for the people to serve God") the Latin motto can be read in the old seal of this Philippine city.

Legacy

Italian, French, Portuguese, Spanish, Romanian, Catalan, Romansh and other Romance languages are direct descendants of Latin. There are also many Latin borrowings in English and Albanian, as well as a few in German, Dutch, Norwegian, Danish and Swedish. Latin is still spoken in Vatican City, a city-state situated in Rome that is the seat of the Catholic Church.

Literature

The works of several hundred ancient authors who wrote in Latin have survived in whole or in part, in substantial works or in fragments to be analyzed in philology. They are in part the subject matter of the field of classics. Their works were published in manuscript form before the invention of printing and are now published in carefully annotated printed editions, such as the Loeb Classical Library, published by Harvard University Press, or the Oxford Classical Texts, published by Oxford University Press.

Latin translations of modern literature such as: The Hobbit, Treasure Island, Robinson Crusoe, Paddington Bear, Winnie the Pooh, The Adventures of Tintin, Asterix, Harry Potter, Le Petit Prince, Max and Moritz, How the Grinch Stole Christmas!, The Cat in the Hat, and a book of fairy tales, "fabulae mirabiles", are intended to garner popular interest in the language. Additional resources include phrasebooks and resources for rendering everyday phrases and concepts into Latin, such as Meissner's Latin Phrasebook.

Inscriptions

Some inscriptions have been published in an internationally agreed, monumental, multivolume series, the Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum (CIL). Authors and publishers vary, but the format is about the same: volumes detailing inscriptions with a critical apparatus stating the provenance and relevant information. The reading and interpretation of these inscriptions is the subject matter of the field of epigraphy. About 270,000 inscriptions are known.

Influence on present-day languages

The Latin influence in English has been significant at all stages of its insular development. In the Middle Ages, borrowing from Latin occurred from ecclesiastical usage established by Saint Augustine of Canterbury in the 6th century or indirectly after the Norman Conquest, through the Anglo-Norman language. From the 16th to the 18th centuries, English writers cobbled together huge numbers of new words from Latin and Greek words, dubbed "inkhorn terms", as if they had spilled from a pot of ink. Many of these words were used once by the author and then forgotten, but some useful ones survived, such as 'imbibe' and 'extrapolate'. Many of the most common polysyllabic English words are of Latin origin through the medium of Old French. Romance words make respectively 59%, 20% and 14% of English, German and Dutch vocabularies. Those figures can rise dramatically when only non-compound and non-derived words are included.

The influence of Roman governance and Roman technology on the less-developed nations under Roman dominion led to the adoption of Latin phraseology in some specialized areas, such as science, technology, medicine, and law. For example, the Linnaean system of plant and animal classification was heavily influenced by Historia Naturalis, an encyclopedia of people, places, plants, animals, and things published by Pliny the Elder. Roman medicine, recorded in the works of such physicians as Galen, established that today's medical terminology would be primarily derived from Latin and Greek words, the Greek being filtered through the Latin. Roman engineering had the same effect on scientific terminology as a whole. Latin law principles have survived partly in a long list of Latin legal terms.

A few international auxiliary languages have been heavily influenced by Latin. Interlingua is sometimes considered a simplified, modern version of the language.[dubious ] Latino sine Flexione, popular in the early 20th century, is Latin with its inflections stripped away, among other grammatical changes.

The Logudorese dialect of the Sardinian language and Standard Italian are the two closest contemporary languages to Latin.

Education

Throughout European history, an education in the classics was considered crucial for those who wished to join literate circles. This also was true in the United States where many of the nation's founders obtained a classically based education in grammar schools or from tutors. Admission to Harvard in the Colonial era required that the applicant "Can readily make and speak or write true Latin prose and has skill in making verse . . ." Latin Study and the classics were emphasized in American secondary schools and colleges well into the Antebellum era.

Instruction in Latin is an essential aspect. In today's world, a large number of Latin students in the US learn from Wheelock's Latin: The Classic Introductory Latin Course, Based on Ancient Authors. This book, first published in 1956, was written by Frederic M. Wheelock, who received a PhD from Harvard University. Wheelock's Latin has become the standard text for many American introductory Latin courses.

The numbers of people studying Latin varies significantly by country. In the United Kingdom, Latin is available in around 2.3% of state primary schools, representing a significant increase in availability. In Germany, over 500,000 students study Latin each year, representing a decrease from over 800,000 in 2008. Latin is still required for some University courses, but this has become less frequent.

The Living Latin movement attempts to teach Latin in the same way that living languages are taught, as a means of both spoken and written communication. It is available in Vatican City and at some institutions in the US, such as the University of Kentucky and Iowa State University. The British Cambridge University Press is a major supplier of Latin textbooks for all levels, such as the Cambridge Latin Course series. It has also published a subseries of children's texts in Latin by Bell & Forte, which recounts the adventures of a mouse called Minimus.

In the United Kingdom, the Classical Association encourages the study of antiquity through various means, such as publications and grants. The University of Cambridge, the Open University, a number of independent schools, for example Eton, Harrow, Haberdashers' Aske's Boys' School, Merchant Taylors' School, and Rugby, and The Latin Programme/Via Facilis, a London-based charity, run Latin courses. In the United States and in Canada, the American Classical League supports every effort to further the study of classics. Its subsidiaries include the National Junior Classical League (with more than 50,000 members), which encourages high school students to pursue the study of Latin, and the National Senior Classical League, which encourages students to continue their study of the classics into college. The league also sponsors the National Latin Exam. Classicist Mary Beard wrote in The Times Literary Supplement in 2006 that the reason for learning Latin is because of what was written in it.

Official status

Latin was or is the official language of European states:

Hungary – Latin was an official language in the Kingdom of Hungary from the 11th century to the mid 19th century, when Hungarian became the exclusive official language in 1844. The best known Latin language poet of Croatian-Hungarian origin was Janus Pannonius.

Hungary – Latin was an official language in the Kingdom of Hungary from the 11th century to the mid 19th century, when Hungarian became the exclusive official language in 1844. The best known Latin language poet of Croatian-Hungarian origin was Janus Pannonius. Croatia – Latin was the official language of Croatian Parliament (Sabor) from the 13th to the 19th century (1847). The oldest preserved records of the parliamentary sessions (Congregatio Regni totius Sclavonie generalis) – held in Zagreb (Zagabria), Croatia – date from 19 April 1273. An extensive Croatian Latin literature

exists. Latin was used on Croatian coins on even years until 1 January

2023, when Croatia adopted the Euro as its official currency.

Croatia – Latin was the official language of Croatian Parliament (Sabor) from the 13th to the 19th century (1847). The oldest preserved records of the parliamentary sessions (Congregatio Regni totius Sclavonie generalis) – held in Zagreb (Zagabria), Croatia – date from 19 April 1273. An extensive Croatian Latin literature

exists. Latin was used on Croatian coins on even years until 1 January

2023, when Croatia adopted the Euro as its official currency. Poland, Kingdom of Poland – officially recognised and widely used between the 10th and 18th centuries, commonly used in foreign relations and popular as a second language among some of the nobility.

Poland, Kingdom of Poland – officially recognised and widely used between the 10th and 18th centuries, commonly used in foreign relations and popular as a second language among some of the nobility.

Phonology

The ancient pronunciation of Latin has been reconstructed; among the data used for reconstruction are explicit statements about pronunciation by ancient authors, misspellings, puns, ancient etymologies, the spelling of Latin loanwords in other languages, and the historical development of Romance languages.

Consonants

The consonant phonemes of Classical Latin are as follows:

|

|

Labial | Dental | Palatal | Velar | Glottal | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| plain | labial | ||||||

| Plosive | voiced | b | d |

|

ɡ | ɡʷ |

|

| voiceless | p | t |

|

k | kʷ |

| |

| Fricative | voiced |

|

(z) |

|

|

|

|

| voiceless | f | s |

|

|

|

h | |

| Nasal | m | n |

|

(ŋ) |

|

| |

| Rhotic |

|

r |

|

|

|

| |

| Approximant |

|

l | j |

|

w |

| |

/z/ was not native to Classical Latin. It appeared in Greek loanwords starting around the first century BC, when it was probably pronounced (at least by educated speakers) [z] initially and doubled [zz] between vowels, in accordance with its pronunciation in Koine Greek. In Classical Latin poetry, the letter ⟨z⟩ between vowels always counts as two consonants for metrical purposes. The consonant ⟨b⟩ usually sounds as [b]; however, when ⟨t⟩ or ⟨s⟩ follows ⟨b⟩ then it is pronounced as in [pt] or [ps]. In Latin, ⟨q⟩ is always followed by the vowel ⟨u⟩. Together they make a [kʷ] sound.

In Old and Classical Latin, the Latin alphabet had no distinction between uppercase and lowercase, and the letters ⟨J U W⟩ did not exist. In place of ⟨J U⟩, ⟨I V⟩ were used, respectively; ⟨I V⟩ represented both vowels and consonants. Most of the letter forms were similar to modern uppercase, as can be seen in the inscription from the Colosseum shown at the top of the article.

The spelling systems used in Latin dictionaries and modern editions of Latin texts, however, normally use ⟨j u⟩ in place of Classical-era ⟨i v⟩. Some systems use ⟨j v⟩ for the consonant sounds /j w/ except in the combinations ⟨gu su qu⟩ for which ⟨v⟩ is never used.

Some notes concerning the mapping of Latin phonemes to English graphemes are given below:

| Latin grapheme |

Latin phoneme |

English examples |

|---|---|---|

| ⟨c⟩, ⟨k⟩ | [k] | Always as k in sky (/skaɪ/) |

| ⟨t⟩ | [t] | As t in stay (/steɪ/) |

| ⟨s⟩ | [s] | As s in say (/seɪ/) |

| ⟨g⟩ | [ɡ] | Always as g in good (/ɡʊd/) |

| [ŋ] | Before ⟨n⟩, as ng in sing (/sɪŋ/) | |

| ⟨n⟩ | [n] | As n in man (/mæn/) |

| [ŋ] | Before ⟨c⟩, ⟨x⟩, and ⟨g⟩, as ng in sing (/sɪŋ/) | |

| ⟨l⟩ | [l] | When doubled ⟨ll⟩ and before ⟨i⟩, as "light L", [l̥] in link ([l̥ɪnk]) (l exilis) |

| [ɫ] | In all other positions, as "dark L", [ɫ] in bowl ([boʊɫ]) (l pinguis) | |

| ⟨qu⟩ | [kʷ] | Similar to qu in squint (/skwɪnt/) |

| ⟨u⟩ | [w] | Sometimes at the beginning of a syllable, or after ⟨g⟩ and ⟨s⟩, as /w/ in wine (/waɪn/) |

| ⟨i⟩ | [j] | Sometimes at the beginning of a syllable, as y (/j/) in yard (/jɑɹd/) |

| [ij] | "y" (/j/), in between vowels, becomes "i-y", being pronounced as parts of two separate syllables, as in capiō (/kapiˈjo:/) | |

| ⟨x⟩ | [ks] | A letter representing ⟨c⟩ + ⟨s⟩: as x in English axe (/æks/) |

In Classical Latin, as in modern Italian, double consonant letters were pronounced as long consonant sounds distinct from short versions of the same consonants. Thus the nn in Classical Latin annus "year" (and in Italian anno) is pronounced as a doubled /nn/ as in English unnamed. (In English, distinctive consonant length or doubling occurs only at the boundary between two words or morphemes, as in that example.)

Vowels

Simple vowels

| Front | Central | Back | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Close | iː ɪ | ʊ uː | |

| Mid | eː ɛ | ɔ oː | |

| Open | a aː |

|

In Classical Latin, ⟨U⟩ did not exist as a letter distinct from V; the written form ⟨V⟩ was used to represent both a vowel and a consonant. ⟨Y⟩ was adopted to represent upsilon in loanwords from Greek, but it was pronounced like ⟨u⟩ and ⟨i⟩ by some speakers. It was also used in native Latin words by confusion with Greek words of similar meaning, such as sylva and ὕλη.

Classical Latin distinguished between long and short vowels. Then, long vowels, except for ⟨i⟩, were frequently marked using the apex, which was sometimes similar to an acute accent ⟨Á É Ó V́ Ý⟩. Long /iː/ was written using a taller version of ⟨I⟩, called i longa "long I": ⟨ꟾ⟩. In modern texts, long vowels are often indicated by a macron ⟨ā ē ī ō ū⟩, and short vowels are usually unmarked except when it is necessary to distinguish between words, when they are marked with a breve ⟨ă ĕ ĭ ŏ ŭ⟩. However, they would also signify a long vowel by writing the vowel larger than other letters in a word or by repeating the vowel twice in a row. The acute accent, when it is used in modern Latin texts, indicates stress, as in Spanish, rather than length.

Although called long vowels, their exact quality in Classical Latin is different from short vowels. The difference is described in the table below:

| Latin grapheme |

Latin phone |

modern examples |

|---|---|---|

| ⟨a⟩ | [a] | similar to the a in part (/paɹt/) |

| [aː] | similar to the a in father (/fɑːðəɹ/) | |

| ⟨e⟩ | [ɛ] | as e in pet (/pɛt/) |

| [eː] | similar to e in hey (/heɪ/) | |

| ⟨i⟩ | [ɪ] | as i in pit (/pɪt/) |

| [iː] | similar to i in machine (/məʃiːn/) | |

| ⟨o⟩ | [ɔ] | as o in port (/pɔɹt/) |

| [oː] | similar to o in post (/poʊst/) | |

| ⟨u⟩ | [ʊ] | as u in put (/pʊt/) |

| [uː] | similar to ue in true (/tɹuː/) | |

| ⟨y⟩ | [ʏ] | does not exist in English, closest approximation is the u in mule |

| [yː] | does not exist in English, closest approximation is the u in cute |

This difference in quality is posited by W. Sidney Allen in his book Vox Latina. However, Andrea Calabrese has disputed this assertion, based in part upon the observation that in Sardinian and some Lucanian dialects, each long and short vowel pair merged, as opposed to in Italo-Western languages in which short /i/ and /u/ merged with long /eː/ and /o:/ (c.f. Latin 'siccus', Italian 'secco', and Sardinian 'siccu').

A vowel letter followed by ⟨m⟩ at the end of a word, or a vowel letter followed by ⟨n⟩ before ⟨s⟩ or ⟨f⟩, represented a short nasal vowel, as in monstrum [mõːstrũ].

Diphthongs

Classical Latin had several diphthongs. The two most common were ⟨ae au⟩. ⟨oe⟩ was fairly rare, and ⟨ui eu ei⟩ were very rare, at least in native Latin words. There has also been debate over whether ⟨ui⟩ is truly a diphthong in Classical Latin, due to its rarity, absence in works of Roman grammarians, and the roots of Classical Latin words (i.e. hui ce to huic, quoi to cui, etc.) not matching or being similar to the pronunciation of classical words if ⟨ui⟩ were to be considered a diphthong.

The sequences sometimes did not represent diphthongs. ⟨ae⟩ and ⟨oe⟩ also represented a sequence of two vowels in different syllables in aēnus [aˈeː.nʊs] "of bronze" and coēpit [kɔˈeː.pɪt] "began", and ⟨au ui eu ei ou⟩ represented sequences of two vowels or of a vowel and one of the semivowels /j w/, in cavē [ˈka.weː] "beware!", cuius [ˈkʊj.jʊs] "whose", monuī [ˈmɔn.ʊ.iː] "I warned", solvī [ˈsɔɫ.wiː] "I released", dēlēvī [deːˈleː.wiː] "I destroyed", eius [ˈɛj.jʊs] "his", and novus [ˈnɔ.wʊs] "new".

Old Latin had more diphthongs, but most of them changed into long vowels in Classical Latin. The Old Latin diphthong ⟨ai⟩ and the sequence ⟨āī⟩ became Classical ⟨ae⟩. Old Latin ⟨oi⟩ and ⟨ou⟩ changed to Classical ⟨ū⟩, except in a few words whose ⟨oi⟩ became Classical ⟨oe⟩. These two developments sometimes occurred in different words from the same root: for instance, Classical poena "punishment" and pūnīre "to punish". Early Old Latin ⟨ei⟩ usually monophthongized to a later Old Latin ⟨ē⟩, to Classical ⟨ī⟩.

By the late Roman Empire, ⟨ae oe⟩ had merged with ⟨e ē⟩. During the Classical period this sound change was present in some rural dialects, but deliberately avoided by well-educated speakers.

| Front | Back | |

|---|---|---|

| Close | ui /ui̯/ | |

| Mid | ei /ei̯/ eu /eu̯/ |

oe /oe̯/ ou /ou̯/ |

| Open | ae /ae̯/ au /au̯/ | |

Syllables

Syllables in Latin are signified by the presence of diphthongs and vowels. The number of syllables is the same as the number of vowel sounds.

Further, if a consonant separates two vowels, it will go into the syllable of the second vowel. When there are two consonants between vowels, the last consonant will go with the second vowel. An exception occurs when a phonetic stop and liquid come together. In this situation, they are thought to be a single consonant, and as such, they will go into the syllable of the second vowel.

Length

Syllables in Latin are considered either long or short (less often called "heavy" and "light" respectively). Within a word, a syllable may either be long by nature or long by position. A syllable is long by nature if it has a diphthong or a long vowel. On the other hand, a syllable is long by position if the vowel is followed by more than one consonant.

Stress

There are two rules that define which syllable is stressed in Classical Latin.

- In a word with only two syllables, the emphasis will be on the first syllable.

- In a word with more than two syllables, there are two cases.

- If the second-to-last syllable is long, that syllable will have stress.

- If the second-to-last syllable is not long, the syllable before that one will be stressed instead.

Orthography

Latin was written in the Latin alphabet (A, B, C, D, E, F, G, H, I, K, L, M, N, O, P, Q, R, S, T, V, X), derived from the Etruscan alphabet, which was in turn drawn from the Greek alphabet and ultimately the Phoenician alphabet. This alphabet has continued to be used over the centuries as the script for the Romance, Celtic, Germanic, Baltic, Finnic and many Slavic languages (Polish, Slovak, Slovene, Croatian, Bosnian, Serbian and Czech); and it has been adopted by many languages around the world, including Vietnamese, the Austronesian languages, many Turkic languages, and most languages in sub-Saharan Africa, the Americas and Oceania, making it by far the world's single most widely used writing system.

The number of letters in the Latin alphabet has varied. When it was first derived from the Etruscan alphabet, it contained only 21 letters. Later, G was added to represent /ɡ/, which had previously been spelled C, and Z ceased to be included in the alphabet, as the language then had no voiced alveolar fricative. The letters Y and Z were later added to represent Greek letters, upsilon and zeta respectively, in Greek loanwords.

W was created in the 11th century from VV. It represented /w/ in Germanic languages, not Latin, which still uses V for the purpose. J was distinguished from the original I only during the late Middle Ages, as was the letter U from V. Although some Latin dictionaries use J, it is rarely used for Latin text, as it was not used in classical times, but many other languages use it.

Punctuation

Classical Latin did not contain sentence punctuation, letter case, or interword spacing, but apices were sometimes used to distinguish length in vowels and the interpunct was used at times to separate words.

The first line of Catullus 3 ("Mourn, O Venuses and Cupids") was originally written as:

| simply | lv́géteóveneréscupidinésqve |

|---|---|

| with long I | lv́géteóveneréscupIdinésqve |

| with interpunct | lv́géte·ó·venerés·cupidinésqve |

It would be rendered in a modern edition as:

| simply | Lugete, o Veneres Cupidinesque |

|---|---|

| with macrons | Lūgēte, ō Venerēs Cupīdinēsque |

| with apices | Lúgéte, ó Venerés Cupídinésque |

The Roman cursive script is commonly found on the many wax tablets excavated at sites such as forts, an especially extensive set having been discovered at Vindolanda on Hadrian's Wall in Britain. Most notable is the fact that while most of the Vindolanda tablets show spaces between words, spaces were avoided in monumental inscriptions from that era.

Alternative scripts

Occasionally, Latin has been written in other scripts:

- The Praeneste fibula is a 7th-century BC pin with an Old Latin inscription written using the Etruscan script.

- The rear panel of the early 8th-century Franks Casket has an inscription that switches from Old English in Anglo-Saxon runes to Latin in Latin script and to Latin in runes.

Grammar

Latin is a synthetic, fusional language in the terminology of linguistic typology. Words involve an objective semantic element and markers (usually suffixes) specifying the grammatical use of the word, expressing gender, number, and case in adjectives, nouns, and pronouns (declension) and verbs to denote person, number, tense, voice, mood, and aspect (conjugation). Some words are uninflected and undergo neither process, such as adverbs, prepositions, and interjections.

Latin inflection can result in words with much ambiguity: For example, amābit, "he/she/it will love", is formed from amā-, a future tense morpheme -bi- and a third person singular morpheme, -t, the last of which -t does not express masculine, feminine, or neuter gender. A major task in understanding Latin phrases and clauses is to clarify such ambiguities by an analysis of context.

Nouns

A regular Latin noun belongs to one of five main declensions, a group of nouns with similar inflected forms. The declensions are identified by the genitive singular form of the noun.

- The first declension, with a predominant ending letter of a, is signified by the genitive singular ending of -ae.

- The second declension, with a predominant ending letter of us, is signified by the genitive singular ending of -i.

- The third declension, with a predominant ending letter of i, is signified by the genitive singular ending of -is.

- The fourth declension, with a predominant ending letter of u, is signified by the genitive singular ending of -ūs.

- The fifth declension, with a predominant ending letter of e, is signified by the genitive singular ending of -ei.

There are seven Latin noun cases, which also apply to adjectives and pronouns and mark a noun's syntactic role in the sentence by means of inflections. Thus, word order is not as important in Latin as it is in English, which is less inflected. The general structure and word order of a Latin sentence can therefore vary. The cases are as follows:

- Nominative – used when the noun is the subject or a predicate nominative. The thing or person acting: the girl ran: puella cucurrit, or cucurrit puella

- Genitive – used when the noun is the possessor of or connected with an object: "the horse of the man", or "the man's horse"; in both instances, the word man would be in the genitive case when it is translated into Latin. It also indicates the partitive, in which the material is quantified: "a group of people"; "a number of gifts": people and gifts would be in the genitive case. Some nouns are genitive with special verbs and adjectives: The cup is full of wine. (Poculum plēnum vīnī est.) The master of the slave had beaten him. (Dominus servī eum verberāverat.)

- Dative – used when the noun is the indirect object of the sentence, with special verbs, with certain prepositions, and if it is used as agent, reference, or even possessor: The merchant hands the stola to the woman. (Mercātor fēminae stolam trādit.)

- Accusative – used when the noun is the direct object of the subject, as the object of a preposition demonstrating place to which, and sometimes to indicate a duration of time: The man killed the boy. (Vir puerum necāvit.)

- Ablative – used when the noun demonstrates separation or movement from a source, cause, agent or instrument or when the noun is used as the object of certain prepositions, and to indicate a specific place in time.; adverbial: You walked with the boy. (Cum puerō ambulāvistī.)

- Vocative – used when the noun is used in a direct address. The vocative form of a noun is often the same as the nominative, with the exception of second-declension nouns ending in -us. The -us becomes an -e in the vocative singular. If it ends in -ius (such as fīlius), the ending is just -ī (filī), as distinct from the nominative plural (filiī) in the vocative singular: "Master!" shouted the slave. ("Domine!" clāmāvit servus.)

- Locative – used to indicate a location (corresponding to the English "in" or "at"). It is far less common than the other six cases of Latin nouns and usually applies to cities and small towns and islands along with a few common nouns, such as the words domus (house), humus (ground), and rus (country). In the singular of the first and second declensions, its form coincides with the genitive (Roma becomes Romae, "in Rome"). In the plural of all declensions and the singular of the other declensions, it coincides with the ablative (Athēnae becomes Athēnīs, "at Athens"). In the fourth-declension word domus, the locative form, domī ("at home") differs from the standard form of all other cases.

Latin lacks both definite and indefinite articles so puer currit can mean either "the boy is running" or "a boy is running".

Adjectives

There are two types of regular Latin adjectives: first- and second-declension and third-declension. They are so-called because their forms are similar or identical to first- and second-declension and third-declension nouns, respectively. Latin adjectives also have comparative and superlative forms. There are also a number of Latin participles.

Latin numbers are sometimes declined as adjectives. See Numbers below.

First- and second-declension adjectives are declined like first-declension nouns for the feminine forms and like second-declension nouns for the masculine and neuter forms. For example, for mortuus, mortua, mortuum (dead), mortua is declined like a regular first-declension noun (such as puella (girl)), mortuus is declined like a regular second-declension masculine noun (such as dominus (lord, master)), and mortuum is declined like a regular second-declension neuter noun (such as auxilium (help)).

Third-declension adjectives are mostly declined like normal third-declension nouns, with a few exceptions. In the plural nominative neuter, for example, the ending is -ia (omnia (all, everything)), and for third-declension nouns, the plural nominative neuter ending is -a or -ia (capita (heads), animalia (animals)) They can have one, two or three forms for the masculine, feminine, and neuter nominative singular.

Participles

Latin participles, like English participles, are formed from a verb. There are a few main types of participles: Present Active Participles, Perfect Passive Participles, Future Active Participles, and Future Passive Participles.

Prepositions

Latin sometimes uses prepositions, depending on the type of prepositional phrase being used. Most prepositions are followed by a noun in either the accusative or ablative case: "apud puerum" (with the boy), with "puerum" being the accusative form of "puer", boy, and "sine puero" (without the boy), "puero" being the ablative form of "puer". A few adpositions, however, govern a noun in the genitive (such as "gratia" and "tenus").

Verbs

A regular verb in Latin belongs to one of four main conjugations. A conjugation is "a class of verbs with similar inflected forms." The conjugations are identified by the last letter of the verb's present stem. The present stem can be found by omitting the -re (-rī in deponent verbs) ending from the present infinitive form. The infinitive of the first conjugation ends in -ā-re or -ā-ri (active and passive respectively): amāre, "to love", hortārī, "to exhort"; of the second conjugation by -ē-re or -ē-rī: monēre, "to warn", verērī, "to fear;" of the third conjugation by -ere, -ī: dūcere, "to lead", ūtī, "to use"; of the fourth by -ī-re, -ī-rī: audīre, "to hear", experīrī, "to attempt". The stem categories descend from Indo-European and can therefore be compared to similar conjugations in other Indo-European languages.

Irregular verbs are verbs that do not follow the regular conjugations in the formation of the inflected form. Irregular verbs in Latin are esse, "to be"; velle, "to want"; ferre, "to carry"; edere, "to eat"; dare, "to give"; ire, "to go"; posse, "to be able"; fieri, "to happen"; and their compounds.

There are six simple tenses in Latin (present, imperfect, future, perfect, pluperfect and future perfect), three moods (indicative, imperative and subjunctive, in addition to the infinitive, participle, gerund, gerundive and supine), three persons (first, second and third), two numbers (singular and plural), two voices (active and passive) and two aspects (perfective and imperfective). Verbs are described by four principal parts:

- The first principal part is the first-person singular, present tense, active voice, indicative mood form of the verb. If the verb is impersonal, the first principal part will be in the third-person singular.

- The second principal part is the present active infinitive.

- The third principal part is the first-person singular, perfect active indicative form. Like the first principal part, if the verb is impersonal, the third principal part will be in the third-person singular.

- The fourth principal part is the supine form, or alternatively, the nominative singular of the perfect passive participle form of the verb. The fourth principal part can show one gender of the participle or all three genders (-us for masculine, -a for feminine and -um for neuter) in the nominative singular. The fourth principal part will be the future participle if the verb cannot be made passive. Most modern Latin dictionaries, if they show only one gender, tend to show the masculine; but many older dictionaries instead show the neuter, as it coincides with the supine. The fourth principal part is sometimes omitted for intransitive verbs, but strictly in Latin, they can be made passive if they are used impersonally, and the supine exists for such verbs.

The six simple tenses of Latin are divided into two systems: the present system, which is made up of the present, imperfect and future forms, and the perfect system, which is made up of the perfect, pluperfect and future perfect forms. Each simple tense has a set of endings corresponding to the person, number, and voice of the subject. Subject (nominative) pronouns are generally omitted for the first (I, we) and second (you) persons except for emphasis.

The table below displays the common inflected endings for the indicative mood in the active voice in all six tenses. For the future tense, the first listed endings are for the first and second conjugations, and the second listed endings are for the third and fourth conjugations:

| Tense | Singular | Plural | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st Person | 2nd Person | 3rd Person | 1st Person | 2nd Person | 3rd Person | |

| Present | -ō/m | -s | -t | -mus | -tis | -nt |

| Future | -bō, -am | -bis, -ēs | -bit, -et | -bimus, -ēmus | -bitis, -ētis | -bunt, -ent |

| Imperfect | -bam | -bās | -bat | -bāmus | -bātis | -bant |

| Perfect | -ī | -istī | -it | -imus | -istis | -ērunt |

| Future Perfect | -erō | -eris/erīs | -erit | -erimus/-erīmus | -eritis/-erītis | -erint |

| Pluperfect | -eram | -erās | -erat | -erāmus | -erātis | -erant |

Deponent verbs

Some Latin verbs are deponent, causing their forms to be in the passive voice but retain an active meaning: hortor, hortārī, hortātus sum (to urge).

Vocabulary

As Latin is an Italic language, most of its vocabulary is likewise Italic, ultimately from the ancestral Proto-Indo-European language. However, because of close cultural interaction, the Romans not only adapted the Etruscan alphabet to form the Latin alphabet but also borrowed some Etruscan words into their language, including persona "mask" and histrio "actor". Latin also included vocabulary borrowed from Oscan, another Italic language.

After the Fall of Tarentum (272 BC), the Romans began Hellenising, or adopting features of Greek culture, including the borrowing of Greek words, such as camera (vaulted roof), sumbolum (symbol), and balineum (bath). This Hellenisation led to the addition of "Y" and "Z" to the alphabet to represent Greek sounds. Subsequently, the Romans transplanted Greek art, medicine, science and philosophy to Italy, paying almost any price to entice Greek skilled and educated persons to Rome and sending their youth to be educated in Greece. Thus, many Latin scientific and philosophical words were Greek loanwords or had their meanings expanded by association with Greek words, as ars (craft) and τέχνη (art).

Because of the Roman Empire's expansion and subsequent trade with outlying European tribes, the Romans borrowed some northern and central European words, such as beber (beaver), of Germanic origin, and bracae (breeches), of Celtic origin. The specific dialects of Latin across Latin-speaking regions of the former Roman Empire after its fall were influenced by languages specific to the regions. The dialects of Latin evolved into different Romance languages.

During and after the adoption of Christianity into Roman society, Christian vocabulary became a part of the language, either from Greek or Hebrew borrowings or as Latin neologisms. Continuing into the Middle Ages, Latin incorporated many more words from surrounding languages, including Old English and other Germanic languages.

Over the ages, Latin-speaking populations produced new adjectives, nouns, and verbs by affixing or compounding meaningful segments. For example, the compound adjective, omnipotens, "all-powerful", was produced from the adjectives omnis, "all", and potens, "powerful", by dropping the final s of omnis and concatenating. Often, the concatenation changed the part of speech, and nouns were produced from verb segments or verbs from nouns and adjectives.

Numbers

In ancient times, numbers in Latin were written only with letters. Today, the numbers can be written with the Arabic numbers as well as with Roman numerals. The numbers 1, 2 and 3 and every whole hundred from 200 to 900 are declined as nouns and adjectives, with some differences.

| ūnus, ūna, ūnum (masculine, feminine, neuter) | I | one |

| duo, duae, duo (m., f., n.) | II | two |

| trēs, tria (m./f., n.) | III | three |

| quattuor | IIII or IV | four |

| quīnque | V | five |

| sex | VI | six |

| septem | VII | seven |

| octō | IIX or VIII | eight |

| novem | VIIII or IX | nine |

| decem | X | ten |

| quīnquāgintā | L | fifty |

| centum | C | one hundred |

| quīngentī, quīngentae, quīngenta (m., f., n.) | D | five hundred |

| mīlle | M | one thousand |

The numbers from 4 to 100 do not change their endings. As in modern descendants such as Spanish, the gender for naming a number in isolation is masculine, so that "1, 2, 3" is counted as ūnus, duo, trēs.

Example text

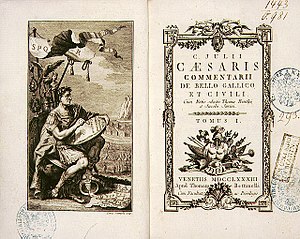

Commentarii de Bello Gallico, also called De Bello Gallico (The Gallic War), written by Gaius Julius Caesar, begins with the following passage:

Gallia est omnis divisa in partes tres, quarum unam incolunt Belgae, aliam Aquitani, tertiam qui ipsorum lingua Celtae, nostra Galli appellantur. Hi omnes lingua, institutis, legibus inter se differunt. Gallos ab Aquitanis Garumna flumen, a Belgis Matrona et Sequana dividit. Horum omnium fortissimi sunt Belgae, propterea quod a cultu atque humanitate provinciae longissime absunt, minimeque ad eos mercatores saepe commeant atque ea quae ad effeminandos animos pertinent important, proximique sunt Germanis, qui trans Rhenum incolunt, quibuscum continenter bellum gerunt. Qua de causa Helvetii quoque reliquos Gallos virtute praecedunt, quod fere cotidianis proeliis cum Germanis contendunt, cum aut suis finibus eos prohibent aut ipsi in eorum finibus bellum gerunt. Eorum una pars, quam Gallos obtinere dictum est, initium capit a flumine Rhodano, continetur Garumna flumine, Oceano, finibus Belgarum; attingit etiam ab Sequanis et Helvetiis flumen Rhenum; vergit ad septentriones. Belgae ab extremis Galliae finibus oriuntur; pertinent ad inferiorem partem fluminis Rheni; spectant in septentrionem et orientem solem. Aquitania a Garumna flumine ad Pyrenaeos montes et eam partem Oceani quae est ad Hispaniam pertinet; spectat inter occasum solis et septentriones.

The same text may be marked for all long vowels (before any possible elisions at word boundary) with apices over vowel letters, including customarily before "nf" and "ns" where a long vowel is automatically produced:

Gallia est omnis dívísa in partés trés, quárum únam incolunt Belgae, aliam Aquítání, tertiam quí ipsórum linguá Celtae, nostrá Gallí appellantur. Hí omnés linguá, ínstitútís, légibus inter sé differunt. Gallós ab Aquítánís Garumna flúmen, á Belgís Mátrona et Séquana dívidit. Hórum omnium fortissimí sunt Belgae, proptereá quod á cultú atque húmánitáte próvinciae longissimé absunt, miniméque ad eós mercátórés saepe commeant atque ea quae ad efféminandós animós pertinent important, proximíque sunt Germánís, quí tráns Rhénum incolunt, quibuscum continenter bellum gerunt. Quá dé causá Helvétií quoque reliquós Gallós virtúte praecédunt, quod feré cotídiánís proeliís cum Germánís contendunt, cum aut suís fínibus eós prohibent aut ipsí in eórum fínibus bellum gerunt. Eórum úna pars, quam Gallós obtinére dictum est, initium capit á flúmine Rhodanó, continétur Garumná flúmine, Óceanó, fínibus Belgárum; attingit etiam ab Séquanís et Helvétiís flúmen Rhénum; vergit ad septentriónés. Belgae ab extrémís Galliae fínibus oriuntur; pertinent ad ínferiórem partem flúminis Rhéní; spectant in septentriónem et orientem sólem. Aquítánia á Garumná flúmine ad Pýrénaeós montés et eam partem Óceaní quae est ad Hispániam pertinet; spectat inter occásum sólis et septentriónés.