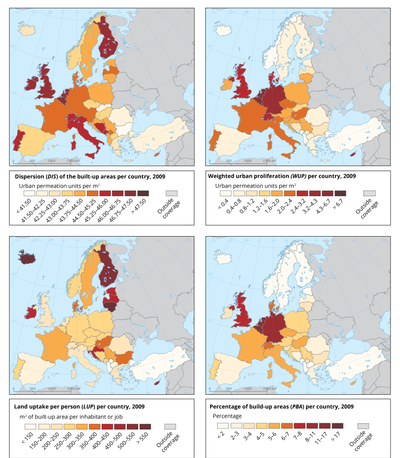

Measures for urban sprawl in Europe: upper left the Dispersion of the built-up area (DIS), upper right the Weighted urban proliferation (WUP)

View of suburban development in the Phoenix metropolitan area

Urban sprawl or suburban sprawl mainly refers to the

unrestricted growth in many urban areas of housing, commercial

development, and roads over large expanses of land, with little concern

for urban planning. In addition to describing a particular form of urbanization, the term also relates to the social and environmental consequences associated with this development. In Continental Europe the term "peri-urbanisation" is often used to denote similar dynamics and phenomena, although the term urban sprawl is currently being used by the European Environment Agency.

There is widespread disagreement about what constitutes sprawl and how

to quantify it. For example, some commentators measure sprawl only with

the average number of residential units per acre in a given area. But

others associate it with decentralization (spread of population without a well-defined centre), discontinuity (leapfrog development, as defined below), segregation of uses, and so forth.

The term urban sprawl is highly politicized, and almost always has negative connotations. It is criticized for causing environmental degradation, intensifying segregation

and undermining the vitality of existing urban areas and attacked on

aesthetic grounds. Due to the pejorative meaning of the term, few openly

support urban sprawl as such. The term has become a rallying cry for

managing urban growth.

Definition

The term "urban sprawl" was first used in an article in The Times in 1955 as a negative comment on the state of London's outskirts. Definitions of sprawl vary; researchers in the field acknowledge that the term lacks precision.

Batty et al. defined sprawl as "uncoordinated growth: the expansion of

community without concern for its consequences, in short, unplanned,

incremental urban growth which is often regarded unsustainable."

Bhatta et al. wrote in 2010 that despite a dispute over the precise

definition of sprawl there is a "general consensus that urban sprawl is

characterized by [an] unplanned and uneven pattern of growth, driven by

multitude of processes and leading to inefficient resource utilization."

This picture shows the metropolitan areas of the Northeast Megalopolis of the United States demonstrating urban sprawl, including far-flung suburbs and exurbs illuminated at night.

Reid Ewing has shown that sprawl has typically been characterized as urban developments

exhibiting at least one of the following characteristics: low-density

or single-use development, strip development, scattered development,

and/or leapfrog development (areas of development interspersed with vacant land).

He argued that a better way to identify sprawl was to use indicators

rather than characteristics because this was a more flexible and less

arbitrary method. He proposed using "accessibility" and "functional open space" as indicators. Ewing's approach has been criticized for assuming that sprawl is defined by negative characteristics.

What constitutes sprawl may be considered a matter of degree and

will always be somewhat subjective under many definitions of the term. Ewing has also argued that suburban development does not, per se constitute sprawl depending on the form it takes,

although Gordon & Richardson have argued that the term is sometimes

used synonymously with suburbanization in a pejorative way.

Metropolitan Los Angeles

for example, despite popular notions of being a sprawling city, is the

densest metropolitan region in the US, being denser than the New York metropolitan area and the San Francisco Bay Area.

Essentially, most of metropolitan Los Angeles is built at more uniform

low to moderate density, leading to a much higher overall density for

the entire region. This is in contrast to cities such as New York, San

Francisco or Chicago which have extremely compact, high-density cores

but are surrounded by large areas of extremely low density.

The international cases of sprawl often draw into question the

definition of the term and what conditions are necessary for urban

growth to be considered sprawl. Metropolitan regions such Greater Mexico City, Delhi National Capital Region and Beijing, are often regarded as sprawling despite being relatively dense and mixed use.

Examples

According

to the National Resources Inventory (NRI), about 8,900 square

kilometres (2.2 million acres) of land in the United States was

developed between 1992 and 2002. Presently, the NRI classifies

approximately 100,000 more square kilometres (40,000 square miles) (an

area approximately the size of Kentucky) as developed than the Census Bureau

classifies as urban. The difference in the NRI classification is that

it includes rural development, which by definition cannot be considered

to be "urban" sprawl. Currently, according to the 2000 Census, approximately 2.6 percent of the U.S. land area is urban.

Approximately 0.8 percent of the nation's land is in the 37 urbanized

areas with more than 1,000,000 population. In 2002, these 37 urbanized

areas supported around 40% of the total American population.

Nonetheless, some urban areas like Detroit

have expanded geographically even while losing population. But it was

not just urbanized areas in the U.S. that lost population and sprawled

substantially. According to data in "Cities and Automobile Dependence"

by Kenworthy and Laube (1999), urbanized area population losses occurred

while there was an expansion of sprawl between 1970 and 1990 in Amsterdam, the Netherlands; Brussels, Belgium; Copenhagen, Denmark; Frankfurt, Hamburg and Munich, Germany; and Zurich, Switzerland, albeit without the dismantling of infrastructure that occurred in the United States.

Characteristics

Despite

the lack of a clear agreed upon description of what defines sprawl most

definitions often associate the following characteristics with sprawl.

Traffic congestion in sprawling São Paulo, Brazil, which, according to Time magazine, has the world's worst traffic jams.

Single-use development

This refers to a situation where commercial, residential, institutional and industrial areas

are separated from one another. Consequently, large tracts of land are

devoted to a single use and are segregated from one another by open

space, infrastructure, or other barriers. As a result, the places where

people live, work, shop, and recreate are far from one another, usually

to the extent that walking, transit use and bicycling are impractical,

so all these activities generally require a car. The degree to which different land uses are mixed together is often used as an indicator of sprawl in studies of the subject.

Job sprawl and spatial mismatch

Job sprawl is another land use symptom of urban sprawl and car-dependent

communities. It is defined as low-density, geographically spread-out

patterns of employment, where the majority of jobs in a given

metropolitan area are located outside of the main city's central business district

(CBD), and increasingly in the suburban periphery. It is often the

result of urban disinvestment, the geographic freedom of employment

location allowed by predominantly car-dependent commuting patterns of

many American suburbs, and many companies' desire to locate in

low-density areas that are often more affordable and offer potential for

expansion. Spatial mismatch is related to job sprawl and economic environmental justice.

Spatial mismatch is defined as the situation where poor urban,

predominantly minority citizens are left without easy access to

entry-level jobs, as a result of increasing job sprawl and limited

transportation options to facilitate a reverse commute to the suburbs.

Job sprawl has been documented and measured in various ways. It

has been shown to be a growing trend in America's metropolitan areas. The Brookings Institution has published multiple articles on the topic. In 2005, author Michael Stoll

defined job sprawl simply as jobs located more than 5-mile (8.0 km)

radius from the CBD, and measured the concept based on year 2000 U.S. Census data. Other ways of measuring the concept with more detailed rings around the CBD include a 2001 article by Edward Glaeser

and Elizabeth Kneebone's 2009 article, which show that sprawling urban

peripheries are gaining employment while areas closer to the CBD are

losing jobs.

These two authors used three geographic rings limited to a 35-mile

(56 km) radius around the CBD: 3 miles (4.8 km) or less, 3 to 10 miles

(16 km), and 10 to 35 miles (56 km). Kneebone's study showed the

following nationwide breakdown for the largest metropolitan areas in

2006: 21.3% of jobs located in the inner ring, 33.6% of jobs in the 3–10

mile ring, and 45.1% in the 10–35 mile ring. This compares to the year

1998 – 23.3%, 34.2%, and 42.5% in those respective rings. The study

shows CBD employment share shrinking, and job growth focused in the

suburban and exurban outer metropolitan rings.

Low-density

Sprawl is often characterized as consisting of low-density development. The exact definition of "low density" is arguable, but a common example is that of single family homes on large lots. Buildings usually have fewer stories and are spaced farther apart, separated by lawns, landscaping, roads or parking lots.

Specific measurements of what constitutes low-density is culturally

relative; for example, in the United States 2–4 houses per acre might be

considered low-density while in the UK 8–12 would still be considered

low-density.

Because more automobiles are used much more land is designated for

parking. The impact of low density development in many communities is

that developed or "urbanized" land is increasing at a faster rate than

the population is growing.

Overall density is often lowered by "leapfrog

development". This term refers to the relationship, or lack thereof,

between subdivisions. Such developments are typically separated by large

green belts,

i.e. tracts of undeveloped land, resulting in an average density far

lower even than the low density indicated by localized per-acre

measurements. This is a 20th and 21st century phenomenon generated by

the current custom of requiring a developer to provide subdivision

infrastructure as a condition of development.

Usually, the developer is required to set aside a certain percentage of

the developed land for public use, including roads, parks and schools.

In the past, when a local government

built all the streets in a given location, the town could expand

without interruption and with a coherent circulation system, because it

had condemnation power.

Private developers generally do not have such power (although they can

sometimes find local governments willing to help), and often choose to

develop on the tracts that happen to be for sale at the time they want

to build, rather than pay extra or wait for a more appropriate location.

Conversion of agricultural land to urban use

Land for sprawl is often taken from fertile agricultural lands,

which are often located immediately surrounding cities; the extent of

modern sprawl has consumed a large amount of the most productive

agricultural land, as well as forest, desert and other wilderness areas. In the United States the seller may avoid tax on profit by using a tax break exempting like-kind exchanges from capital gains tax;

proceeds from the sale are used to purchase agricultural land elsewhere

and the transaction is treated as a "swap" or trade of like assets and

no tax is due. Thus urban sprawl is subsidized by the tax code.

In China, land has been converted from rural to urban use in advance of

demand, leading to vacant rural land intended for future development,

and eventual urban sprawl.

Housing subdivisions

Housing subdivisions are large tracts of land consisting entirely of newly built residences. New Urbanist architectural firm Duany Plater-Zyberk & Company

claim that housing subdivisions "are sometimes called villages, towns,

and neighbourhoods by their developers, which is misleading since those

terms denote places that are not exclusively residential." They are also referred to as developments.

Subdivisions often incorporate curved roads and cul-de-sacs.

These subdivisions may offer only a few places to enter and exit the

development, causing traffic to use high volume collector streets. All

trips, no matter how short, must enter the collector road in a suburban

system.

Lawn

Because the

advent of sprawl meant more land for lower costs, home owners had more

land at their disposal, and the development of the residential lawn after the Second World War became commonplace in suburbs, notably, but not exclusively in North America.

The creation in the early 20th century of country clubs and golf

courses completed the rise of lawn culture in the United States. Lawns now take up a significant amount of land in suburban developments, contributing in no small part to sprawl.

Commercial developments

In

areas of sprawl, commercial use is generally segregated from other

uses. In the U.S. and Canada, these often take the form of strip malls,

which refer to collections of buildings sharing a common parking lot,

usually built on a high-capacity roadway with commercial functions

(i.e., a "strip"). Similar developments in the UK are called Retail

Parks. Strip malls consisting mostly of big box stores or category killers

are sometimes called "power centers" (U.S.). These developments tend to

be low-density; the buildings are single-story and there is ample space

for parking and access for delivery vehicles. This character is

reflected in the spacious landscaping of the parking lots and walkways

and clear signage of the retail establishments. Some strip malls are

undergoing a transformation into Lifestyle centers;

entailing investments in common areas and facilities (plazas, cafes)

and shifting tenancy from daily goods to recreational shopping.

Walmart Supercenter in Luray, Virginia.

Another prominent form of retail development in areas characterized by sprawl is the shopping mall.

Unlike the strip mall, this is usually composed of a single building

surrounded by a parking lot that contains multiple shops, usually

"anchored" by one or more department stores

(Gruen and Smith 1960). The function and size is also distinct from the

strip mall. The focus is almost exclusively on recreational shopping

rather than daily goods. Shopping malls also tend to serve a wider

(regional) public and require higher-order infrastructure such as

highway access and can have floorspaces in excess of a million square

feet (ca. 100,000 m²). Shopping malls are often detrimental to downtown

shopping centres of nearby cities since the shopping malls act as a

surrogate for the city centre

(Crawford 1992). Some downtowns have responded to this challenge by

building shopping centres of their own (Frieden and Sagelyn 1989).

Fast food

chains are often built early in areas with low property values where

the population is expected to boom and where large traffic is predicted,

and set a precedent for future development. Eric Schlosser, in his book Fast Food Nation,

argues that fast food chains accelerate suburban sprawl and help set

its tone with their expansive parking lots, flashy signs, and plastic

architecture (65). Duany Plater Zyberk & Company

believe that this reinforces a destructive pattern of growth in an

endless quest to move away from the sprawl that only results in creating

more of it.

Effects

Environmental

Urban sprawl is associated with a number of negative environmental outcomes.

One of the major environmental problems associated with sprawl is land loss, habitat loss and subsequent reduction in biodiversity. A review by Czech and colleagues finds that urbanization endangers

more species and is more geographically ubiquitous in the mainland

United States than any other human activity. Urban sprawl is disruptive

to native flora & fauna and introduces invasive plants into their environments. Although the effects can be mitigated through careful maintenance of native vegetation, the process of ecological succession and public education, sprawl represents one of the primary threats to biodiversity.

Regions with high birth rates and immigration are therefore faced

with environmental problems due to unplanned urban growth and emerging

megacities such as Kolkata.

Other problems include:

- flooding, which results from increased impervious surfaces for roads and parking

- increased temperatures from heat islands, which leads to a significantly increased risk of mortality in elderly populations.

The urban sprawl of Melbourne.

At the same time, the urban cores of these and nearly all other major cities in the United States, Western Europe, and Japan that did not annex new territory experienced the related phenomena of falling household size and, particularly in the U.S., "white flight", sustaining population losses. This trend has slowed somewhat in recent years, as more people have regained an interest in urban living.

Due to the larger area consumed by sprawling suburbs compared to

urban neighborhoods, more farmland and wildlife habitats are displaced

per resident. As forest cover is cleared and covered with impervious surfaces (concrete and asphalt) in the suburbs, rainfall is less effectively absorbed into the groundwater aquifers. This threatens both the quality and quantity of water supplies. Sprawl increases water pollution as rain water picks up gasoline, motor oil, heavy metals, and other pollutants in runoff from parking lots and roads.

The Chicago metro area, nicknamed "Chicagoland".

Gordon & Richardson have argued that the conversion of

agricultural land to urban use is not a problem due to the increasing

efficiency of agricultural production; they argue that aggregate

agricultural production is still more than sufficient to meet global

food needs despite the expansion of urban land use.

Health

Sprawl leads to increased driving, and increased driving leads to vehicle emissions that contribute to air pollution and its attendant negative impacts on human health.

In addition, the reduced physical activity implied by increased

automobile use has negative health consequences. Sprawl significantly

predicts chronic medical conditions and health-related quality of life,

but not mental health disorders.

The American Journal of Public Health and the American Journal of

Health Promotion, have both stated that there is a significant

connection between sprawl, obesity, and hypertension.

In the years following World War II, when vehicle ownership was

becoming widespread, public health officials recommended the health

benefits of suburbs due to soot and industrial fumes in the city center.

However, air in modern suburbs is not necessarily cleaner than air in

urban neighborhoods.

In fact, the most polluted air is on crowded highways, where people in

suburbs tend to spend more time. On average, suburban residents generate

more per capita pollution and carbon emissions than their urban counterparts because of their increased driving.

Safety

A heavy

reliance on automobiles increases traffic throughout the city as well as

automobile crashes, pedestrian injuries, and air pollution.

Motor vehicle crashes

are the leading cause of death for Americans between the ages of five

and twenty-four and is the leading accident-related cause for all age

groups. Residents of more sprawling areas are generally at greater risk of dying in a car crash due to increased exposure to driving.

Evidence indicates that pedestrians in sprawling areas are at higher

risk than those in denser areas, although the relationship is less clear

than for drivers and passengers in vehicles.

Research covered in the Journal of Economic Issues and State and Local Government Review shows a link between sprawl and emergency medical services response and fire department response delays.

Increased infrastructure/transportation costs

Living

in larger, more spread out spaces generally makes public services more

expensive. Since car usage becomes endemic and public transport often

becomes significantly more expensive, city planners are forced to build

highway and parking infrastructure, which in turn decreases taxable land and revenue, and decreases the desirability of the area adjacent to such structures. Providing services such as water, sewers, and electricity

is also more expensive per household in less dense areas, given that

sprawl increases lengths of power lines and pipes, necessitating higher

maintenance costs.

Residents of low-density areas spend a higher proportion of their income on transportation than residents of high density areas.

The unplanned nature of outward urban development is commonly linked

to increased dependency on cars, which, assuming a citizen commutes

every day of the year, with a ticket cost for a train at 3 pounds, every

year a citizen would spend 1095 pounds on commuting to work, however;

the RAC estimates that the average cost of operating a car in the UK is £5,000 a year, which means that urban sprawl would cause an economic loss of 3905 pounds per year, per person through cars alone.

Major cities – per capita petrol use vs. population density

Social

Urban sprawl may be partly responsible for the decline in social capital

in the United States. Compact neighborhoods can foster casual social

interactions among neighbors, while sprawl creates barriers. Sprawl

tends to replace public spaces with private spaces such as fenced-in

backyards.

Critics of sprawl maintain that sprawl erodes quality of life.

Duany and Plater-Zyberk believe that in traditional neighborhoods the

nearness of the workplace to retail and restaurant space that provides

cafes and convenience stores

with daytime customers is an essential component to the successful

balance of urban life. Furthermore, they state that the closeness of the

workplace to homes also gives people the option of walking or riding a

bicycle to work or school and that without this kind of interaction

between the different components of life the urban pattern quickly falls

apart. James Howard Kunstler has argued that poor aesthetics in suburban environments make them "places not worth caring about", and that they lack a sense of history and identity.

Urban sprawl has class and racial implications in many parts of

the world; the relative homogeneity of many sprawl developments may

reinforce class and racial divides through residential segregation.

Numerous studies link increased population density with increased aggression.

Some people believe that increased population density encourages crime

and anti-social behavior. It is argued that human beings, while social

animals, need significant amounts of social space or they become

agitated and aggressive. However, the relationship between higher densities and increased social pathology has been largely discredited.

Debate

Rural neighborhoods in Morrisville, North Carolina

are rapidly developing into affluent, urbanized neighborhoods and

subdivisions. The two images above are on opposite sides of the same

street.

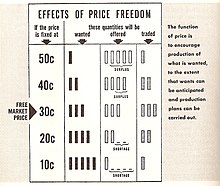

According to Nancy Chin, a large number of effects of sprawl have

been discussed in the academic literature in some detail; however, the

most contentious issues can be reduced "to an older set of arguments,

between those advocating a planning approach and those advocating the

efficiency of the market."

Those who criticize sprawl tend to argue that sprawl creates more

problems than it solves and should be more heavily regulated, while

proponents argue that markets are producing the economically most

efficient settlements possible in most situations, even if problems may

exist.

However, some market oriented commentators believe that the current

patterns of sprawl are in fact the result of distortions of the free

market.

Chin cautions that there is a lack of "reliable empirical evidence to

support the arguments made either for or against sprawl." She mentions

that the lack of a common definition, the need for more quantitative

measures "a broader view both in time and space, and greater comparison

with alternative urban forms" would be necessary to draw firmer

conclusions and conduct more fruitful debates.

Arguments opposing urban sprawl include concrete effects such as

health and environmental issues as well as abstract consequences

including neighborhood vitality. American public policy analyst Randal O'Toole of the Cato Institute, a libertarian think tank,

has argued that sprawl, thanks to the automobile, gave rise to

affordable suburban neighborhoods for middle class and lower class

individuals, including non-whites. He notes that efforts to combat

sprawl often result in subsidizing development in wealthier and whiter

neighborhoods while condemning and demolishing poorer minority

neighborhoods.

Groups that oppose sprawl

The American Institute of Architects and the American Planning Association recommend against sprawl and instead endorses smart, mixed-use development,

including buildings in close proximity to one another that cut down on

automobile use, save energy, and promote walkable, healthy,

well-designed neighborhoods. The Sierra Club, the San Francisco Bay Area's Greenbelt Alliance, 1000 Friends of Oregon

and counterpart organizations nationwide, and other environmental

organizations oppose sprawl and support investment in existing

communities. NumbersUSA, a national organization advocating immigration reduction, also opposes urban sprawl, and its executive director, Roy Beck, specializes in the study of this issue.

Consumer preference

One

of the primary debates around suburban sprawl is the extent to which

sprawl is the result of consumer preference. Some, such as Peter Gordon,

a professor of planning and economics at the University of Southern

California's School of Urban Planning and Development, argue that most

households have shown a clear preference for low-density living and that

this is a fact that should not be ignored by planners.

Gordon and his frequent collaborator, Harry Richardson have argued that

"The principle of consumer sovereignty has played a powerful role in

the increase in America’s wealth and in the welfare of its citizens.

Producers (including developers) have responded rapidly to households’

demands. It is a giant step backward to interfere with this effective

process unless the benefits of intervention substantially exceed its

cost."

They argue that sprawl generates enough benefits for consumers that

they continue to choose it as a form of development over alternative

forms, as demonstrated by the continued focus on sprawl type

developments by most developers.

However, other academics such as Reid Ewing argue that while a large

segment of people prefer suburban living that does not mean that sprawl

itself is preferred by consumers, and that a large variety of suburban

environments satisfy consumer demand, including areas that mitigate the

worst effects of sprawl. Others, for example Kenneth T. Jackson

have argued that since low-density housing is often (notably in the

U.S.A.) subsidized in a variety of ways, consumers' professed

preferences for this type of living may be over-stated.

Automobile dependency

A majority of Californians live, commute, and work in the vast and extensive web of Southern California freeways.

Whether urban sprawl does increase problems of automobile dependency and whether conversely, policies of smart growth can reduce them have been fiercely contested issues over several decades. An influential study in 1989 by Peter Newman and Jeff Kenworthy compared 32 cities across North America, Australia, Europe and Asia. The study has been criticised for its methodology

but the main finding that denser cities, particularly in Asia, have

lower car use than sprawling cities, particularly in North America, has

been largely accepted although the relationship is clearer at the

extremes across continents than it is within countries where conditions

are more similar.

Within cities, studies from across many countries (mainly in the

developed world) have shown that denser urban areas with greater mixture

of land use and better public transport tend to have lower car use than

less dense suburban and ex-urban residential areas. This usually holds

true even after controlling for socio-economic factors such as

differences in household composition and income.

This does not necessarily imply that suburban sprawl causes high car

use, however. One confounding factor, which has been the subject of many

studies, is residential self-selection:

people who prefer to drive tend to move towards low density suburbs,

whereas people who prefer to walk, cycle or use transit tend to move

towards higher density urban areas, better served by public transport.

Some studies have found that, when self-selection is controlled for, the

built environment has no significant effect on travel behaviour. More recent studies using more sophisticated methodologies have generally refuted these findings: density, land use and public transport accessibility

can influence travel behaviour, although social and economic factors,

particularly household income, usually exert a stronger influence.

Those not opposed to low density development argue that traffic

intensities tend to be less, traffic speeds faster and, as a result,

ambient air pollution is lower. Kansas City, Missouri

is often cited as an example of ideal low-density development, with

congestion below the mean and home prices below comparable Midwestern

cities. Wendell Cox and Randal O'Toole are leading figures supporting lower density development.

Longitudinal (time-lapse) studies of commute times in major

metropolitan areas in the United States have shown that commute times

decreased for the period 1969 to 1995 even though the geographic size of

the city increased.

Other studies suggest, however, that possible personal benefits from

commute time savings have been at the expense of environmental costs in

the form of longer average commute distances, rising vehicles-miles-traveled (VMT) per worker, and despite road expansions, worsening traffic congestion.

Paradox of intensification

Reviewing the evidence on urban intensification, smart growth and their effects on travel behaviour Melia et al. (2011) found support for the arguments of both supporters and opponents of smart growth

measures to counteract urban sprawl. Planning policies that increase

population densities in urban areas do tend to reduce car use, but the

effect is a weak one, so doubling the population density of a particular

area will not halve the frequency or distance of car use.

These findings led them to propose the paradox of intensification, which states:

Ceteris paribus,

urban intensification which increases population density will reduce

per capita car use, with benefits to the global environment, but will

also increase concentrations of motor traffic, worsening the local

environment in those locations where it occurs.

Risk of increased housing prices

There

is also some concern that anti-sprawl policies will increase housing

prices. Some research suggests Oregon has had the largest housing

affordability loss in the nation, but other research shows that Portland's price increases are comparable to other Western cities.

In Australia, it is claimed by some that housing affordability

has hit "crisis levels" due to "urban consolidation" policies

implemented by state governments. In Sydney, the ratio of the price of a house relative to income is 9:1. The issue has at times been debated between the major political parties.

Proposed alternatives

Many

critics concede that sprawl produces some negative externalities;

however there is some dispute about the most effective way to reduce

these negative effects. Gordon & Richardson for example argue that

the costs of building new public transit is disproportionate to the

actual environmental or economic benefits, that land use restrictions

will increase the cost of housing and restrict economic opportunity,

that infill possibilities are too limited to make a major difference to

the structure of American cities, and that the government would need to

coerce most people to live in a way that they do not want to in order to

substantially change the impact of sprawl.

They argue that the property market should be deregulated to allow

different people to live as they wish, while providing a framework of market based fees (such as emission fees, congestion charging or road pricing) to mitigate many of the problems associated with sprawl such as congestion and increased pollution.

Alternative development styles

Early attempts at combatting urban sprawl

The Metropolitan Green Belt first proposed by the London County Council in 1935.

Starting in the early 20th century, environmentalist opposition to urban sprawl began to coalesce, with roots in the garden city movement, as well as pressure from campaign groups such as the Campaign to Protect Rural England (CPRE).

Under Herbert Morrison's 1934 leadership of the London County Council,

the first formal proposal was made by the Greater London Regional

Planning Committee "to provide a reserve supply of public open spaces

and of recreational areas and to establish a green belt or girdle of open space". It was again included in an advisory Greater London Plan prepared by Patrick Abercrombie in 1944. The Town and Country Planning Act of 1947 expressly incorporated green belts into all further national urban developments.

New provisions for compensation in the 1947 Town and Country Planning Act allowed local authorities around the country to incorporate green belt proposals in their first development plans.

The codification of Green Belt policy and its extension to areas other

than London came with the historic Circular 42/55 inviting local

planning authorities to consider the establishment of Green Belts. The

first urban growth boundary in the U.S. was in Fayette County, Kentucky in 1958.

Contemporary anti-sprawl initiatives

The

term 'smart growth' has been particularly used in North America. The

terms 'compact city' or 'urban intensification' are often used to

describe similar concepts in Europe and particularly the UK where it has

influenced government policy and planning practice in recent years.

The state of Oregon enacted a law in 1973 limiting the area urban areas could occupy, through urban growth boundaries. As a result, Portland, the state's largest urban area, has become a leader in smart growth

policies that seek to make urban areas more compact (they are called

urban consolidation policies). After the creation of this boundary, the

population density of the urbanized area increased somewhat (from 1,135 in 1970 to 1,290 per km² in 2000).

While the growth boundary has not been tight enough to vastly increase

density, the consensus is that the growth boundaries have protected

great amounts of wild areas and farmland around the metro area.

Many parts of the San Francisco Bay Area have also adopted urban

growth boundaries; 25 of its cities and 5 of its counties have urban

growth boundaries. Many of these were adopted with the support and

advocacy of Greenbelt Alliance, a non-profit land conservation and urban planning organization.

In other areas, the design principles of District Regionalism and New Urbanism have been employed to combat urban sprawl. The concept of Circular flow land use management has been developed in Europe to reduce land take by urban sprawl through promoting inner-city and brownfield development.

While cities such as Los Angeles

are well known for sprawling suburbs, policies and public opinion are

changing. Transit-oriented development, in which higher-density

mixed-use areas are permitted or encouraged near transit stops is

encouraging more compact development in certain areas-particularly those

with light and heavy rail transit systems.

Bicycles are the preferred means of travel in many countries. Also, bicycles are permitted in public transit.

Businesses in areas of some towns where bicycle use is high are

thriving. Bicycles and transit are contributing in two important ways

toward the success of businesses:

- First, is that on average the people living the closest to these business districts have more money to spend locally because they don't spend as much on their cars.

- Second, because these people rely more on bicycling, walking and transit than on driving, they tend to focus more of their commerce on locally owned neighborhood businesses that are convenient for them to reach.

Walkability is a measure of how friendly an area is to walking.

Walkability has many health, environmental, and economic benefits.

However, evaluating walkability is challenging because it requires the

consideration of many subjective factors. Factors influencing walkability include the presence or absence and quality of footpaths, sidewalks

or other pedestrian right-of-ways, traffic and road conditions, land

use patterns, building accessibility, and safety, among others. Walkability is an important concept in sustainable urban design.