Economists generally believe that a sudden deflationary shock is a problem in a modern economy because it increases the real value of debt, especially if the deflation is unexpected. Deflation may also aggravate recessions and lead to a deflationary spiral (see later section).

Some economists argue that prolonged deflationary periods are related to the underlying of technological progress in an economy, because as productivity increases (TFP), the cost of goods decreases.

Deflation usually happens when supply is high (when excess production occurs), when demand is low (when consumption decreases), or when the money supply decreases (sometimes in response to a contraction created from careless investment or a credit crunch) or because of a net capital outflow from the economy. It can also occur when there is too much competition and too little market concentration.

Causes and corresponding types

In the IS–LM model (investment and saving equilibrium – liquidity preference and money supply equilibrium model), deflation is caused by a shift in the supply and demand curve for goods and services. This in turn can be caused by an increase in supply, a fall in demand, or both.

When prices are falling, consumers have an incentive to delay purchases and consumption until prices fall further, which in turn reduces overall economic activity. When purchases are delayed, productive capacity is idled and investment falls, leading to further reductions in aggregate demand. This is the deflationary spiral. The way to reverse this quickly would be to introduce an economic stimulus. The government could increase productive spending on things like infrastructure or the central bank could start expanding the money supply.

Deflation is also related to risk aversion, where investors and buyers will start hoarding money because its value is now increasing over time. This can produce a liquidity trap or it may lead to shortages that entice investments yielding more jobs and commodity production. A central bank cannot, normally, charge negative interest for money, and even charging zero interest often produces less stimulative effect than slightly higher rates of interest. In a closed economy, this is because charging zero interest also means having zero return on government securities, or even negative return on short maturities. In an open economy it creates a carry trade, and devalues the currency. A devalued currency produces higher prices for imports without necessarily stimulating exports to a like degree.

Deflation is the natural condition of economies when the supply of money is fixed, or does not grow as quickly as population and the economy. When this happens, the available amount of hard currency per person falls, in effect making money more scarce, and consequently, the purchasing power of each unit of currency increases. Deflation also occurs when improvements in production efficiency lower the overall price of goods. Competition in the marketplace often prompts those producers to apply at least some portion of these cost savings into reducing the asking price for their goods. When this happens, consumers pay less for those goods, and consequently, deflation has occurred, since purchasing power has increased.

Rising productivity and reduced transportation cost created structural deflation during the accelerated productivity era from 1870 to 1900, but there was mild inflation for about a decade before the establishment of the Federal Reserve in 1913. There was inflation during World War I, but deflation returned again after the war and during the 1930s depression. Most nations abandoned the gold standard in the 1930s so that there is less reason to expect deflation, aside from the collapse of speculative asset classes, under a fiat monetary system with low productivity growth.

In mainstream economics, deflation may be caused by a combination of the supply and demand for goods and the supply and demand for money, specifically the supply of money going down and the supply of goods going up. Historic episodes of deflation have often been associated with the supply of goods going up (due to increased productivity) without an increase in the supply of money, or (as with the Great Depression and possibly Japan in the early 1990s) the demand for goods going down combined with a decrease in the money supply. Studies of the Great Depression by Ben Bernanke have indicated that, in response to decreased demand, the Federal Reserve of the time decreased the money supply, hence contributing to deflation.

Causes include, on the demand side:

- Growth deflation

- Hoarding

And on the supply side:

- Bank credit deflation

- Debt deflation

- Decision on the money supply side

- Credit deflation

Growth deflation

Growth deflation is an enduring decrease in the real cost of goods and services as the result of technological progress, accompanied by competitive price cuts, resulting in an increase in aggregate demand.

A structural deflation existed from the 1870s until the cycle upswing that started in 1895. The deflation was caused by the decrease in the production and distribution costs of goods. It resulted in competitive price cuts when markets were oversupplied. The mild inflation after 1895 was attributed to the increase in gold supply that had been occurring for decades. There was a sharp rise in prices during World War I, but deflation returned at the war's end. By contrast, under a fiat monetary system, there was high productivity growth from the end of World War II until the 1960s, but no deflation.

Historically not all episodes of deflation correspond with periods of poor economic growth.

Productivity and deflation are discussed in a 1940 study by the Brookings Institution that gives productivity by major US industries from 1919 to 1939, along with real and nominal wages. Persistent deflation was clearly understood as being the result of the enormous gains in productivity of the period. By the late 1920s, most goods were over supplied, which contributed to high unemployment during the Great Depression.

Bank credit deflation

Bank credit deflation is a decrease in the bank credit supply due to bank failures or increased perceived risk of defaults by private entities or a contraction of the money supply by the central bank.

Debt deflation

Debt deflation is a complicated phenomenon associated with the end of long-term credit cycles. It was proposed as a theory by Irving Fisher (1933) to explain the deflation of the Great Depression.

Money supply-side deflation

From a monetarist perspective, deflation is caused primarily by a reduction in the velocity of money or the amount of money supply per person.

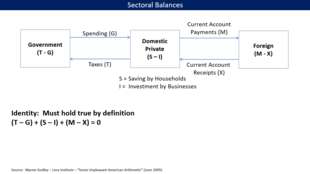

A historical analysis of money velocity and monetary base shows an inverse correlation: for a given percentage decrease in the monetary base the result is a nearly equal percentage increase in money velocity. This is to be expected because monetary base (MB), velocity of base money (VB), price level (P) and real output (Y) are related by definition: MBVB = PY. However, the monetary base is a much narrower definition of money than M2 money supply. Additionally, the velocity of the monetary base is interest-rate sensitive, the highest velocity being at the highest interest rates.

In the early history of the United States, there was no national currency and an insufficient supply of coinage. Banknotes were the majority of the money in circulation. During financial crises, many banks failed and their notes became worthless. Also, banknotes were discounted relative to gold and silver, the discount depended on the financial strength of the bank.

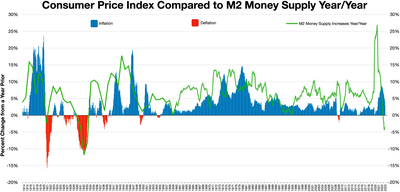

In recent years changes in the money supply have historically taken a long time to show up in the price level, with a rule of thumb lag of at least 18 months. More recently Alan Greenspan cited the time lag as taking between 12 and 13 quarters. Bonds, equities and commodities have been suggested as reservoirs for buffering changes in the money supply.

Credit deflation

In modern credit-based economies, deflation may be caused by the central bank initiating higher interest rates (i.e., to "control" inflation), thereby possibly popping an asset bubble. In a credit-based economy, a slow-down or fall in lending leads to less money in circulation, with a further sharp fall in money supply as confidence reduces and velocity weakens, with a consequent sharp fall-off in demand for employment or goods. The fall in demand causes a fall in prices as a supply glut develops. This becomes a deflationary spiral when prices fall below the costs of financing production, or repaying debt levels incurred at the prior price level. Businesses, unable to make enough profit no matter how low they set prices, are then liquidated. Banks get assets that have fallen dramatically in value since their mortgage loan was made, and if they sell those assets, they further glut supply, which only exacerbates the situation. To slow or halt the deflationary spiral, banks will often withhold collecting on non-performing loans (as in Japan, and most recently America and Spain). This is often no more than a stop-gap measure, because they must then restrict credit, since they do not have money to lend, which further reduces demand, and so on.

Historical examples of credit deflation

In the early economic history of the United States, cycles of inflation and deflation correlated with capital flows between regions, with money being loaned from the financial center in the Northeast to the commodity producing regions of the (mid)-West and South. In a procyclical manner, prices of commodities rose when capital was flowing in, that is, when banks were willing to lend, and fell in the depression years of 1818 and 1839 when banks called in loans. Also, there was no national paper currency at the time and there was a scarcity of coins. Most money circulated as banknotes, which typically sold at a discount according to distance from the issuing bank and the bank's perceived financial strength.

When banks failed their notes were redeemed for bank reserves, which often did not result in payment at par value, and sometimes the notes became worthless. Notes of weak surviving banks traded at steep discounts. During the Great Depression, people who owed money to a bank whose deposits had been frozen would sometimes buy bank books (deposits of other people at the bank) at a discount and use them to pay off their debt at par value.

Deflation occurred periodically in the U.S. during the 19th century (the most important exception was during the Civil War). This deflation was at times caused by technological progress that created significant economic growth, but at other times it was triggered by financial crises – notably the Panic of 1837 which caused deflation through 1844, and the Panic of 1873 which triggered the Long Depression that lasted until 1879. These deflationary periods preceded the establishment of the U.S. Federal Reserve System and its active management of monetary matters. Episodes of deflation have been rare and brief since the Federal Reserve was created (a notable exception being the Great Depression) while U.S. economic progress has been unprecedented.

A financial crisis in England in 1818 caused banks to call in loans and curtail new lending, draining specie out of the U.S. The Bank of the United States also reduced its lending. Prices for cotton and tobacco fell. The price of agricultural commodities also was pressured by a return of normal harvests following 1816, the year without a summer, that caused large scale famine and high agricultural prices.

There were several causes of the deflation of the severe depression of 1839–1843, which included an oversupply of agricultural commodities (importantly cotton) as new cropland came into production following large federal land sales a few years earlier, banks requiring payment in gold or silver, the failure of several banks, default by several states on their bonds and British banks cutting back on specie flow to the U.S.

This cycle has been traced out on a broad scale during the Great Depression. Partly because of overcapacity and market saturation and partly as a result of the Smoot–Hawley Tariff Act, international trade contracted sharply, severely reducing demand for goods, thereby idling a great deal of capacity, and setting off a string of bank failures. A similar situation in Japan, beginning with the stock and real estate market collapse in the early 1990s, was arrested by the Japanese government preventing the collapse of most banks and taking over direct control of several in the worst condition.

Scarcity of official money

The United States had no national paper money until 1862 (greenbacks used to fund the Civil War), but these notes were discounted to gold until 1877. There was also a shortage of U.S. minted coins. Foreign coins, such as Mexican silver, were commonly used. At times banknotes were as much as 80% of currency in circulation before the Civil War. In the financial crises of 1818–19 and 1837–1841, many banks failed, leaving their money to be redeemed below par value from reserves. Sometimes the notes became worthless, and the notes of weak surviving banks were heavily discounted. The Jackson administration opened branch mints, which over time increased the supply of coins. Following the 1848 finding of gold in the Sierra Nevada, enough gold came to market to devalue gold relative to silver. To equalize the value of the two metals in coinage, the US mint slightly reduced the silver content of new coinage in 1853.

When structural deflation appeared in the years following 1870, a common explanation given by various government inquiry committees was a scarcity of gold and silver, although they usually mentioned the changes in industry and trade we now call productivity. However, David A. Wells (1890) notes that the U.S. money supply during the period 1879-1889 actually rose 60%, the increase being in gold and silver, which rose against the percentage of national bank and legal tender notes. Furthermore, Wells argued that the deflation only lowered the cost of goods that benefited from recent improved methods of manufacturing and transportation. Goods produced by craftsmen did not decrease in price, nor did many services, and the cost of labor actually increased. Also, deflation did not occur in countries that did not have modern manufacturing, transportation and communications.

By the end of the 19th century, deflation ended and turned to mild inflation. William Stanley Jevons predicted rising gold supply would cause inflation decades before it actually did. Irving Fisher blamed the worldwide inflation of the pre-WWI years on rising gold supply.

In economies with an unstable currency, barter and other alternate currency arrangements such as dollarization are common, and therefore when the 'official' money becomes scarce (or unusually unreliable), commerce can still continue (e.g., most recently in Zimbabwe). Since in such economies the central government is often unable, even if it were willing, to adequately control the internal economy, there is no pressing need for individuals to acquire official currency except to pay for imported goods.

Currency pegs and monetary unions

If a country pegs its currency to one of another country that features a higher productivity growth or a more favourable unit cost development, it must – to maintain its competitiveness – either become equally more productive or lower its factor prices (e.g., wages). Cutting factor prices fosters deflation. Monetary unions have a similar effect to currency pegs.

Effects

On spending and borrowing

Some believe that, in the absence of large amounts of debt, deflation would be a welcome effect because the lowering of prices increases purchasing power. However, while an increase in the purchasing power of one's money benefits some, it amplifies the sting of debt for others: after a period of deflation, the payments to service a debt represent a larger amount of purchasing power than they did when the debt was first incurred. Consequently, deflation can be thought of as an effective increase in a loan's interest rate. If, as during the Great Depression in the United States, deflation averages 10% per year, even an interest-free loan is unattractive as it must be repaid with money worth 10% more each year.

Under normal conditions, most central banks, such as the Federal Reserve, implement policy by setting a target for a short-term interest rate – the overnight federal funds rate in the U.S. – and enforcing that target by buying and selling securities in open capital markets. When the short-term interest rate hits zero, the central bank can no longer ease policy by lowering its usual interest-rate target. With interest rates near zero, debt relief becomes an increasingly important tool in managing deflation.

In recent times, as loan terms have grown in length and loan financing (or leveraging) is common among many types of investments, the costs of deflation to borrowers has grown larger.

On savings and investments

Deflation can discourage private investment, because there is reduced expectations on future profits when future prices are lower. Consequently, with reduced private investments, spiraling deflation can cause a collapse in aggregate demand. Without the "hidden risk of inflation", it may become more prudent for institutions to hold on to money, and not to spend or invest it (burying money). They are therefore rewarded by saving and holding money. This "hoarding" behavior is seen as undesirable by most economists. Friedrich Hayek, a libertarian Austrian-school economist, wrote that:

It is agreed that hoarding money, whether in cash or in idle balances, is deflationary in its effects. No one thinks that deflation is in itself desirable.

— Hayek (1932)

Compared with inflation

Deflation causes a transfer of wealth from borrowers and holders of illiquid assets to the benefit of savers and of holders of liquid assets and currency, and because confused price signals cause malinvestment in the form of underinvestment. In this sense, its effects are the opposite of inflation, the effect of which is to transfer wealth from currency holders and lenders (savers) and to borrowers, including governments, and cause overinvestment. Whereas inflation encourages short term consumption and can similarly overstimulate investment in projects that may not be worthwhile in real terms (for example, the dot-com and housing bubbles), deflation reduces investment even when there is a real-world demand not being met. In modern economies, deflation is usually associated with economic depression, as occurred in the Great Depression and the Long Depression. Deflation was present during most economic depressions in US history.

Deflationary spiral

A deflationary spiral is a situation where decreases in the price level lead to lower production, which in turn leads to lower wages and demand, which leads to further decreases in the price level. Since reductions in general price level are called deflation, a deflationary spiral occurs when reductions in price lead to a vicious circle, where a problem exacerbates its own cause. In science, this effect is also known as a positive feedback loop. Another economic example of this situation in economics is the bank run.

The Great Depression was regarded by some as a deflationary spiral. A deflationary spiral is the modern macroeconomic version of the general glut controversy of the 19th century. Another related idea is Irving Fisher's theory that excess debt can cause a continuing deflation.

Counteracting deflation

During severe deflation, targeting an interest rate (the usual method of determining how much currency to create) may be ineffective, because even lowering the short-term interest rate to zero may result in a real interest rate which is too high to attract credit-worthy borrowers. In the 21st-century, negative interest rates have been tried, but it cannot be too negative, since people might withdraw cash from bank accounts if they have a negative interest rate. Thus the central bank must directly set a target for the quantity of money (called "quantitative easing") and may use extraordinary methods to increase the supply of money, e.g. purchasing financial assets of a type not usually used by the central bank as reserves (such as mortgage-backed securities). Before he was Chairman of the United States Federal Reserve, Ben Bernanke claimed in 2002, "sufficient injections of money will ultimately always reverse a deflation", although Japan's deflationary spiral was not broken by the amount of quantitative easing provided by the Bank of Japan.

Until the 1930s, it was commonly believed by economists that deflation would cure itself. As prices decreased, demand would naturally increase, and the economic system would correct itself without outside intervention.

This view was challenged in the 1930s during the Great Depression. Keynesian economists argued that the economic system was not self-correcting with respect to deflation and that governments and central banks had to take active measures to boost demand through tax cuts or increases in government spending. Reserve requirements from the central bank were high compared to recent times. So were it not for redemption of currency for gold (in accordance with the gold standard), the central bank could have effectively increased money supply by simply reducing the reserve requirements and through open market operations (e.g., buying treasury bonds for cash) to offset the reduction of money supply in the private sectors due to the collapse of credit (credit is a form of money).

With the rise of monetarist ideas, the focus in fighting deflation was put on expanding demand by lowering interest rates (i.e., reducing the "cost" of money). This view has received criticism in light of the failure of accommodative policies in both Japan and the US to spur demand after stock market shocks in the early 1990s and in 2000–2002, respectively. Austrian economists worry about the inflationary impact of monetary policies on asset prices. Sustained low real rates can cause higher asset prices and excessive debt accumulation. Therefore, lowering rates may prove to be only a temporary palliative, aggravating an eventual debt deflation crisis.

Special borrowing arrangements

When the central bank has lowered nominal interest rates to zero, it can no longer further stimulate demand by lowering interest rates. This is the famous liquidity trap. When deflation takes hold, it requires "special arrangements" to lend money at a zero nominal rate of interest (which could still be a very high real rate of interest, due to the negative inflation rate) in order to artificially increase the money supply.

Capital

Although the values of capital assets are often casually said to deflate when they decline, this usage is not consistent with the usual definition of deflation; a more accurate description for a decrease in the value of a capital asset is economic depreciation. Another term, the accounting conventions of depreciation are standards to determine a decrease in values of capital assets when market values are not readily available or practical.

Historical examples

EU countries

The inflation rate of Greece was negative during three years from 2013 to 2015. The same applies to Bulgaria, Cyprus, Spain, and Slovakia from 2014 to 2016. Greece, Cyprus, Spain, and Slovakia are members of the European monetary union. The Bulgarian currency, the lev, is pegged to the Euro with a fixed exchange rate. In the entire European Union and the Eurozone, a disinflationary development was to be observed in the years 2011 to 2015.

| Year | Bulgaria | Greece | Cyprus | Spain | Slovakia | EU | Eurozone |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2011 | 3.4 | 3.1 | 3.5 | 3.0 | 4.1 | 3.1 | 2.7 |

| 2012 | 2.4 | 1.0 | 3.1 | 2.4 | 3.7 | 2.6 | 2.5 |

| 2013 | 0.4 | −0.9 | 0.4 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.4 |

| 2014 | −1.6 | −1.4 | −0.3 | −0.2 | −0.1 | 0.6 | 0.4 |

| 2015 | −1.1 | −1.1 | −1.5 | −0.6 | −0.3 | 0.1 | 0.2 |

| 2016 | −1.3 | 0.0 | −1.2 | −0.3 | −0.5 | 0.2 | 0.2 |

| 2017 | 1.2 | 1.1 | 0.7 | 2.0 | 1.4 | 1.7 | 1.5 |

Table: Harmonised index of consumer prices. Annual average rate of change (%) (HICP inflation rate). Negative values are highlighted in colour.

Hong Kong

Following the Asian financial crisis in late 1997, Hong Kong experienced a long period of deflation which did not end until the fourth quarter of 2004. Many East Asian currencies devalued following the crisis. The Hong Kong dollar, however, was pegged to the U.S. dollar, leading to an adjustment instead by a deflation of consumer prices. The situation was worsened by the increasingly cheap exports from mainland China, and "weak consumer confidence" in Hong Kong. This deflation was accompanied by an economic slump that was more severe and prolonged than those of the surrounding countries that devalued their currencies in the wake of the Asian financial crisis.

Ireland

In February 2009, Ireland's Central Statistics Office announced that during January 2009, the country experienced deflation, with prices falling by 0.1% from the same time in 2008. This was the first time deflation has hit the Irish economy since 1960. Overall consumer prices decreased by 1.7% in the month.

Brian Lenihan, Ireland's Minister for Finance, mentioned deflation in an interview with RTÉ Radio. According to RTÉ's account, "Minister for Finance Brian Lenihan has said that deflation must be taken into account when Budget cuts in child benefit, public sector pay and professional fees are being considered. Mr Lenihan said month-on-month there has been a 6.6% decline in the cost of living this year."

This interview is notable in that the deflation referred to is not discernibly regarded negatively by the Minister in the interview. The Minister mentions the deflation as an item of data helpful to the arguments for a cut in certain benefits. The alleged economic harm caused by deflation is not alluded to or mentioned by this member of government. This is a notable example of deflation in the modern era being discussed by a senior financial Minister without any mention of how it might be avoided, or whether it should be.

Japan

Deflation started in the early 1990s. The Bank of Japan and the government tried to eliminate it by reducing interest rates and "quantitative easing," but did not create a sustained increase in broad money and deflation persisted. In July 2006, the zero-rate policy was ended.

Systemic reasons for deflation in Japan can be said to include:

- Tight monetary conditions: The Bank of Japan kept monetary policy loose only when inflation was below zero, tightening whenever deflation ends.

- Unfavorable demographics: Japan has an aging population (22.6% over age 65) which has been declining since 2011, as the death rate exceeds the birth rate.

- Fallen asset prices: In the case of Japan asset price deflation was a mean reversion or correction back to the price level that prevailed before the asset bubble. There was a rather large price bubble in stocks and especially real estate in Japan in the 1980s (peaking in late 1989).

- Insolvent companies: Banks lent to companies and individuals that invested in real estate. When real estate values dropped, these loans could not be paid. The banks could try to collect on the collateral (land), but this wouldn't pay off the loan. Banks delayed that decision, hoping asset prices would improve. These delays were allowed by national banking regulators. Some banks made even more loans to these companies that are used to service the debt they already had. This continuing process is known as maintaining an "unrealized loss", and until the assets are completely revalued and/or sold off (and the loss realized), it will continue to be a deflationary force in the economy. Improving bankruptcy law, land transfer law, and tax law have been suggested as methods to speed this process and thus end the deflation.

- Insolvent banks: Banks with a larger percentage of their loans which are "non-performing", that is to say, they are not receiving payments on them, but have not yet written them off, cannot lend more money; they must increase their cash reserves to cover the bad loans.

- Fear of insolvent banks: Japanese people are afraid that banks will collapse so they prefer to buy (United States or Japanese) Treasury bonds instead of saving their money in a bank account. This likewise means the money is not available for lending and therefore economic growth. This means that the savings rate depresses consumption, but does not appear in the economy in an efficient form to spur new investment. People also save by owning real estate, further slowing growth, since it inflates land prices.

- Imported deflation: Japan imports Chinese and other countries' inexpensive consumable goods (due to lower wages and fast growth in those countries) and inexpensive raw materials, many of which reached all time real price minimums in the early 2000s. Thus, prices of imported products are decreasing. Domestic producers must match these prices in order to remain competitive. This decreases prices for many things in the economy, and thus is deflationary.

- Stimulus spending: According to both Austrian and monetarist economic theory, Keynesian stimulus spending actually has a depressing effect. This is because the government is competing against private industry, and usurping private investment dollars. In 1998, for example, Japan produced a stimulus package of more than 16 trillion yen, over half of it public works that would have a quashing effect on an equivalent amount of private, wealth-creating economic activity. Overall, Japan's stimulus packages added up to over one hundred trillion yen, and yet they failed. According to these economic schools, that stimulus money actually perpetuated the problem it was intended to cure.

In November 2009, Japan returned to deflation, according to The Wall Street Journal. Bloomberg L.P. reports that consumer prices fell in October 2009 by a near-record 2.2%. It was not until 2014 that new economic policies laid out by Prime Minister Shinzo Abe finally allowed for significant levels of inflation to return. However, the COVID-19 recession once again led to deflation in 2020, with consumer good prices quickly falling, prompting heavy government stimulus worth over 20% of GDP. As a result, it is likely that deflation will remain as a long-term economic issue for Japan.

United Kingdom

During World War I the British pound sterling was removed from the gold standard. The motivation for this policy change was to finance World War I; one of the results was inflation, and a rise in the gold price, along with the corresponding drop in international exchange rates for the pound. When the pound was returned to the gold standard after the war it was done on the basis of the pre-war gold price, which, since it was higher than equivalent price in gold, required prices to fall to realign with the higher target value of the pound.

The UK experienced deflation of approximately 10% in 1921, 14% in 1922, and 3 to 5% in the early 1930s.

United States

Major deflations in the United States

There have been four significant periods of deflation in the United States.

The first and most severe was during the depression in 1818–1821 when prices of agricultural commodities declined by almost 50%. A credit contraction caused by a financial crisis in England drained specie out of the U.S. The Bank of the United States also contracted its lending. The price of agricultural commodities fell by almost 50% from the high in 1815 to the low in 1821, and did not recover until the late 1830s, although to a significantly lower price level. Most damaging was the price of cotton, the U.S.'s main export. Food crop prices, which had been high because of the famine of 1816 that was caused by the year without a summer, fell after the return of normal harvests in 1818. Improved transportation, mainly from turnpikes, and to a minor extent the introduction of steamboats, significantly lowered transportation costs.

The second was the depression of the late 1830s to 1843, following the Panic of 1837, when the currency in the United States contracted by about 34% with prices falling by 33%. The magnitude of this contraction is only matched by the Great Depression. (See: § Historical examples of credit deflation.) This "deflation" satisfies both definitions, that of a decrease in prices and a decrease in the available quantity of money. Despite the deflation and depression, GDP rose 16% from 1839 to 1843.

The third was after the Civil War, sometimes called The Great Deflation. It was possibly spurred by return to a gold standard, retiring paper money printed during the Civil War:

The Great Sag of 1873–96 could be near the top of the list. Its scope was global. It featured cost-cutting and productivity-enhancing technologies. It flummoxed the experts with its persistence, and it resisted attempts by politicians to understand it, let alone reverse it. It delivered a generation's worth of rising bond prices, as well as the usual losses to unwary creditors via defaults and early calls. Between 1875 and 1896, according to Milton Friedman, prices fell in the United States by 1.7% a year, and in Britain by 0.8% a year.

— Grant's Interest Rate Observer, 10 March 2006

(Note: David A. Wells (1890) gives an account of the period and discusses the great advances in productivity which Wells argues were the cause of the deflation. The productivity gains matched the deflation. Murray Rothbard (2002) gives a similar account.)

The fourth was in 1930–1933 when the rate of deflation was approximately 10 percent/year, part of the United States' slide into the Great Depression, where banks failed and unemployment peaked at 25%.

The deflation of the Great Depression occurred partly because there was an enormous contraction of credit (money), bankruptcies creating an environment where cash was in frantic demand, and when the Federal Reserve was supposed to accommodate that demand, it instead contracted the money supply by 30% in enforcement of its new real bills doctrine, so banks failed one by one (because they were unable to meet the sudden demand for cash – see Bank run). From the standpoint of the Fisher equation (see above), there was a simultaneous drop both in money supply (credit) and the velocity of money which was so profound that price deflation took hold despite the increases in money supply spurred by the Federal Reserve.

Minor deflations in the United States

Throughout the history of the United States, inflation has approached zero and dipped below for short periods of time. This was quite common in the 19th century, and in the 20th century until the permanent abandonment of the gold standard for the Bretton Woods system in 1948. In the past 60 years, the United States has experienced deflation only two times; in 2009 with the Great Recession and in 2015, when the CPI barely broke below 0% at −0.1%.

Some economists believe the United States may have experienced deflation as part of the financial crisis of 2007–2008; compare the theory of debt deflation. Consumer prices dropped 1 percent in October 2008. This was the largest one-month fall in prices in the U.S. since at least 1947. That record was again broken in November 2008 with a 1.7% decline. In response, the Federal Reserve decided to continue cutting interest rates, down to a near-zero range as of December 16, 2008.

In late 2008 and early 2009, some economists feared the U.S. would enter a deflationary spiral. Economist Nouriel Roubini predicted that the United States would enter a deflationary recession, and coined the term "stag-deflation" to describe it. It was the opposite of stagflation, which was the main fear during the spring and summer of 2008. The United States then began experiencing measurable deflation, steadily decreasing from the first measured deflation of −0.38% in March, to July's deflation rate of −2.10%. On the wage front, in October 2009, the state of Colorado announced that its state minimum wage, which was indexed to inflation, was set to be cut, which would be the first time a state had cut its minimum wage since 1938.