Mural of Frederick Douglass, Falls Road, Belfast.

Irish people's history has embraced both a legacy of identification

with the oppressed, and in propagation of the Irish Slaves Myths,

elements of racism.

The Irish slaves myth concerns the use of the term Irish "slaves" as a conflation of the penal transportation and indentured servitude of Irish people during the 17th and 18th centuries. Some white nationalists, and others who want to minimize the hereditary chattel slavery experience of Africans and their descendants, have used the false equivalence myth to promote racism against African Americans[1] or claim that African Americans are too vocal in seeking justice.

The Irish slaves myth has also been invoked by some Irish activists, to

highlight the British oppression of the Irish people and to suppress

the history of Irish involvement in the transatlantic slave trade.

The myth has been in circulation since at least the 1990s and has been disseminated in online memes and social media debates. In 2016, academics and Irish historians wrote to condemn the myth.

Background

The idea that Irish people are slaves has a long history. According to historian Liam Kennedy, the idea was popular among the nineteenth-century Young Ireland movement. John Mitchel was particularly vocal in his claim that the Irish were enslaved, although he supported the transatlantic slave trade of Africans.

Some books have used the term "slaves" for captive Irish people forced from their homes in Ireland and shipped overseas, against their will, to the New World, particularly the British Colonies. The term "slaves" or "bond slaves" was used for a "time-bound" system of years that was not perpetual. The British legal term used was "indentured servants"

whether the servants had volunteered for transport or were kidnapped

and forced aboard ships. However, for centuries, Irish folklore or

various books had referred to the captive servants as Irish "slaves"

even into the 20th century.

During the 17th century, tens of thousands of British and Irish indentured servants immigrated to British America. The majority of these entered into indentured servitude in the Americas for a set number of years willingly in order to pay their way across the Atlantic, but at least 10,000 were transported as punishment for rebellion against English rule in Ireland or for other crimes, then subjected to forced labour for a given period.

During this same period, the Atlantic slave trade was enslaving millions of Africans

and bringing them to the Americas, including the British colonies,

where they were put to work. In Ireland, Africa, and in the Caribbean,

Irish people benefited from the African trade, as slave merchants,

factors, investors, and owners. According to historian Nini Rodgers,

"every group in Ireland produced merchants who benefited from the slave

trade and the expanding slave colonies."

Unlike Irish indentured servants, enslaved Africans generally were

made slaves for life and slave status was imposed on their children at

birth. Both systematically and legally, Africans were subjected to a lifelong, heritable slavery that the Irish never were. African slaves' future descendants became property.

Origins and propagation

The myth is especially popular with apologists for the Confederate States of America, the secessionist slave states of the South during the American Civil War. According to research librarian and independent scholar Liam Hogan, the most influential book to assert the myth was They Were White And They Were Slaves: The Untold History of The Enslavement of Whites In Early America, self-published in the US in 1993 by conspiracy theorist and Holocaust denier Michael A. Hoffman II (who blamed Jews for the African slave trade).

This was followed in Ireland in 2000 by the book To Hell Or Barbados: The Ethnic Cleansing of Ireland by the journalist Sean O'Callaghan.

The book continued Hoffman's themes and introduced the concept of Irish

women being forcibly bred with African men in order to produce mulattos, who are represented as being more valuable than slaves of purely Irish ancestry.

It is not made clear why this is the case, or why it was not possible

to achieve the same result with the physical union of European men and

African women, a far more frequent interracial union. Other authors

repeated these lurid descriptions of Irish women being compelled to have

sex with African men, which have no basis in the historical record. Liam Hogan and other historians have described the book as shoddily researched.

In the Dublin Review of Books,

professor Bryan Fanning states: "The popularity of the 'Irish slaves'

meme cannot simply be blamed on the online propaganda of white

supremacist groups. There are several elements at play beyond the

deliberate falsification of the past. Widespread acceptance online of a

false equivalence between chattel slavery and the treatment of Irish

migrants appears to be rooted in Irish narratives of victimhood that

continue to be articulated within Ireland’s cultural and political

mainstreams."

Irish people's history has embraced both a legacy of identification

with the oppressed, and elements of racism in the service of Irish

nationalism, according to Fanning.

According to The New York Times:

"In America, [O'Callaghan's] book connected the white slave narrative

to an influential ethnic group of over 34 million people, many of whom

had been raised on stories of Irish rebellion against Britain and tales

of anti-Irish bias in America at the turn of the 20th century. From

there, it took off." O'Callaghan's claims were repeated on Irish genealogy websites, the Canadian conspiracy theory website Globalresearch.ca, Niall O'Dowd's IrishCentral, Scientific American and The Daily Kos.

The 2008 article on Globalresearch.ca has been a significant online

source for the myth, having been shared almost a million times by March

2016. The myth has been spread on white nationalist message boards, neo-Nazi websites, the far-right conspiracy website InfoWars, and has been shared millions of times on Facebook.

The myth has been a common trope on the white supremacist website Stormfront since 2003. It has circulated widely in the United States, and has recently begun to become common in Ireland after the "Irish slaves" meme went viral on social media in 2013. After the 2014 arrival of the Black Lives Matter movement, the myth was frequently referenced by right-wing white Americans attempting to undermine it and other African-American civil rights issues, according to Aidan McQuade, director of Anti-Slavery International.

In August 2015, the meme was referred to in the context of debates about the continued flying of the Confederate flag, following the Charleston church shooting. In May 2016, it was referenced by prominent members of the Irish republican party Sinn Féin, after their leader Gerry Adams became involved in a controversy over his use of the word "nigger". Irish Times

columnist Donald Clarke describes the meme as racist, saying "More

commonly we see racists using the myth to belittle the suffering visited

on black slaves and to siphon some sympathy towards their own clan." According to The New York Times, the myth is "often politically motivated" and has been used to create "racist barbs" against African-Americans.

Common elements

Common elements to memes that propagate the myth are:

- The conspiracy theory that historians and the media are covering up Irish slavery.

- That Irish people were enslaved after the Cromwellian invasion of Ireland in 1649.

- Irish slaves were treated worse than African slaves.

- Irish women were forced to reproduce with African men.

- Intending to diminish the discrimination that African-Americans have historically experienced, with memes like "The Irish were slaves, too. We got over it, so why can't you?".

- Using photographs of victims of the Holocaust or 20th century child laborers, claiming that they are Irish slaves.

- A reference to an alleged 1625 declaration by King James II to send thousands of Irish prisoners to the West Indies as slaves. James II had not been even born yet; he was born in 1633 and started his rule in 1685. 1625 saw the end of James I's rule and the rise of Charles I to the throne.

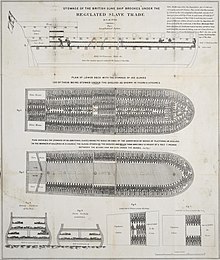

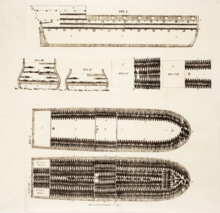

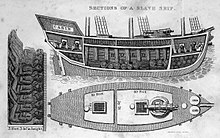

- The substitution of the victims of actual atrocities committed against African slaves with Irish victims. The far-right conspiracy website InfoWars, for instance, substituted the 132 African victims of the 1781 Zong massacre with Irish victims. Several online articles about "Irish slaves" have inflated the number 132 to 1,302. Historian Liam Hogan traces the first juxtaposition of the Zong massacre with Irish suffering to 2002, when James Mullin, chair of the New Jersey-based Irish Famine Curriculum Committee and Education Fund, wrote a lurid article blurring the lines between the history of African enslavement in the British Americas with the history of Irish colonial indentured servitude.

Academic criticism and responses

The Irish Examiner

removed an article that cited John Martin's Globalresearch.ca piece

from its website in early 2016 after 82 writers, historians and

academics wrote an open letter condemning the myth. Scientific American

published a blog post, which was also debunked in the open letter, and

later heavily revised the blog to remove the incorrect historical

material.

Writing in The New York Times, Liam Stack noted that inaccurate "Irish slavery" claims "also appeared on IrishCentral, a leading Irish-American news website." IrishCentral's

publisher Niall O'Dowd then wrote an op-ed in which he states that

"there is no way the Irish slave experience mirrored the extent or level

of centuries-long degradation that African slaves went through." The op-ed then goes on to draw comparisons between indentured servitude and slavery. Liam Hogan, among others, criticized IrishCentral for being slow to remove the articles from its website, and for the ahistoric comparison in the editorial.

Sean O'Callaghan's book To Hell or Barbados in particular

has been criticised by, among others, Dr Nini Rodgers, who stated that

his narrative appeared to arise from his horror at seeing white people

being on a level with blacks. Bryan Fanning notes the book ignored scholarly research.

Historian Mark Auslander, an anthropologist and director of the Museum of Culture and Environment at Central Washington University,

states that the current racial climate is leaning toward denial of

certain events in history, saying "There is a strange war on memory

that's going on right now, denying the facts of chattel slavery, or

claiming to have learned on Facebook or social media that, say, Irish

slavery was worse, that white people were enslaved as well. Not true."

Matthew Reilly, a postdoctoral fellow at Brown University with an academic background in Barbadian slavery,

asserts that "The Irish slave myth is not supported by the historical

evidence." Historians note that unlike slaves, most indentured servants

willingly entered into contracts with another person, only served for a

finite period, did not pass their unfree status on to their children,

and were still considered human. Historian Donald Akenson, writing in If the Irish Ran the World: Montserrat, 1630-1730, states that on the island of Montserrat, "White indentured servitude was so very different from black slavery as to be from another galaxy of human experience."

According to Hogan, the debate over the exact definition of slavery, as

well as a tendency of some Irish nationalists to gloss over the ways in

which Irish people benefitted from the African slave trade, allowed for

a grey area in historical discourse that was then seized upon as a

political weapon by white supremacists.

Fanning writes: ". . .narratives which represent the Irish as having

been slaves are hardly harmless. From the 1840s onwards racism was

pressed into the service of Irish nationalism. . . versions of Irish

history which obfuscate past Irish racisms have proven to be a toxic

export . . ."