From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| Star Trek | |

|---|---|

The Star Trek logo as it appears in J. J. Abrams's Star Trek

|

|

| Creator | Gene Roddenberry |

| Original work | Star Trek: The Original Series |

| Print publications | |

| Novels | List of novels |

| Comics | List of comics |

| Films and television | |

| Films |

Main article: Star Trek (film franchise)

|

| Television series | |

| Games | |

| Video games | List of games |

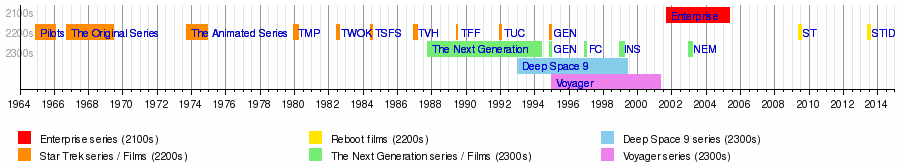

Star Trek is an American science fiction entertainment franchise created by Gene Roddenberry and under the ownership of CBS and Paramount.[Note 1] Star Trek: The Original Series and its live action TV spin-off shows, Star Trek: The Next Generation, Star Trek: Deep Space Nine, Star Trek: Voyager, and Star Trek: Enterprise as well as the Star Trek film series make up the main canon. Star Trek: The Animated Series is debated and the expansive library of Star Trek novels and comics, although still part of the franchise, are generally considered non-canon.[Note 2]

The first series, now referred to as "The Original Series", debuted in 1966 and ran for three seasons on NBC. It followed the interstellar adventures of James T. Kirk and the crew of the starship Enterprise, an exploration vessel of a 23rd-century interstellar "United Federation of Planets". In creating the first "Star Trek", Roddenberry was inspired by Westerns such as Wagon Train, along with the Horatio Hornblower novels and Gulliver's Travels. In fact, the original show was almost entitled, 'Wagon Train to the Stars.' These adventures continued in the short-lived Star Trek: The Animated Series and six feature films. Four spin-off television series were eventually produced: Star Trek: The Next Generation, followed the crew of a new starship Enterprise set a century after the original series; Star Trek: Deep Space Nine and Star Trek: Voyager, set contemporaneously with The Next Generation; and Star Trek: Enterprise, set before the original series, in the early days of human interstellar travel. Four additional The Next Generation feature films were produced. In 2009, the film franchise underwent a relaunch with a prequel to the original series set in an alternate timeline titled simply Star Trek. This film featured a new cast portraying younger versions of the crew from the original Enterprise.[Note 3] A sequel to this film, Star Trek Into Darkness, premiered on May 16, 2013. A thirteenth theatrical feature, the next sequel to Into Darkness, has been confirmed for release

in July 2016, to coincide with the franchise's 50th anniversary.

Star Trek has been a cult phenomenon for decades.[1] Fans of the franchise are called Trekkies or Trekkers. The franchise spans a wide range of spin-offs including games, figurines, novels, toys, and comics. Star Trek had a themed attraction in Las Vegas that opened in 1998 and closed in September 2008. At least two museum exhibits of props travel the world. The series has its own full-fledged constructed language, Klingon. Several parodies have been made of Star Trek. Its fans, despite the end of Star Trek episodes on TV, have produced several fan productions to fill that void.

Star Trek is noted for its influence on the world outside of science fiction. It has been cited as an inspiration for several technological inventions such as the cell phone. Moreover, the show is noted for its progressive for its era civil rights stances. The original series included one of television's first multiracial casts. Star Trek references can be found throughout popular culture from movies such as the submarine thriller Crimson Tide to the cartoon series South Park.

Conception and setting

As early as 1964, Gene Roddenberry drafted a proposal for the science fiction series that would become Star Trek. Although he publicly marketed it as a Western in outer space—a so-called "Wagon Train to the Stars" (like the popular Western TV series)[2]—he privately told friends that he was modeling it on Jonathan Swift's Gulliver's Travels, intending each episode to act on two levels: as a suspenseful adventure story and as a morality tale.[3]

Most Star Trek stories depict the adventures of humans[Note 4] and aliens who serve in Starfleet, the space-borne humanitarian and peacekeeping armada of the United Federation of Planets. The protagonists have altruistic values, and must apply these ideals to difficult dilemmas. Many of the conflicts and political dimensions of Star Trek represent allegories of contemporary cultural realities. Star Trek: The Original Series addressed issues of the 1960s,[4] just as later spin-offs have reflected issues of their respective decades. Issues depicted in the various series include war and peace, the value of personal loyalty, authoritarianism, imperialism, class warfare, economics, racism, religion, human rights, sexism, feminism, and the role of technology.[5] Roddenberry stated: "[By creating] a new world with new rules, I could make statements about sex, religion, Vietnam, politics, and intercontinental missiles. Indeed, we did make them on Star Trek: we were sending messages and fortunately they all got by the network."[6]

Roddenberry intended the show to have a progressive political agenda reflective of the emerging counter-culture of the youth movement, though he was not fully forthcoming to the networks about this. He wanted Star Trek to show humanity what it might develop into, if only it would learn from the lessons of the past, most specifically by ending violence. An extreme example is the alien species, the Vulcans, who had a violent past but learned to control their emotions. Roddenberry also gave Star Trek an anti-war message and depicted the United Federation of Planets as an ideal, optimistic version of the United Nations.[7] His efforts were opposed by the network because of concerns over marketability, e.g., they opposed Roddenberry's insistence that the Enterprise have a racially diverse crew.[8]

However, Star Trek has also been accused of evincing racism and imperialism by frequently depicting Starfleet and the Federation trying to impose their values and customs on other planets.[9][10]

History and production

Beginnings

Captain James T. Kirk and Commander Spock, played by William Shatner and Leonard Nimoy, pictured here in The Original Series.

In early 1964, Roddenberry presented a brief treatment for a proposed Star Trek TV series to Desilu Productions comparing it to Wagon Train, "a Wagon Train to the stars."[11] Desilu worked with Roddenberry to develop the treatment into a script, which was then pitched to NBC.[12]

NBC paid to make a pilot, "The Cage", starring Jeffrey Hunter as Enterprise Captain Christopher Pike. NBC rejected The Cage, but the executives were still impressed with the concept, and made the unusual decision to commission a second pilot: "Where No Man Has Gone Before".[12]

The first regular episode ("The Man Trap") of Star Trek: The Original Series aired on Thursday, September 8, 1966.[13] While the show initially enjoyed high ratings, the average rating of the show at the end of its first season dropped to 52nd (out of 94 programs).

Unhappy with the show's ratings, NBC threatened to cancel the show during its second season.[14] The show's fan base, led by Bjo Trimble, conducted an unprecedented letter-writing campaign, petitioning the network to keep the show on the air.[15][16] NBC renewed the show, but moved it from primetime to the "Friday night death slot", and substantially reduced its budget.[17] In protest Roddenberry resigned as producer and reduced his direct involvement in Star Trek, which led to Fred Freiberger becoming producer for the show's third and final season.[Note 5] Despite another letter-writing campaign, NBC cancelled the series after three seasons and 79 episodes.[12]

Rebirth

After the original series was cancelled, Paramount Studios, which had bought the series from Desilu, licensed the broadcast syndication rights to help recoup the production losses. Reruns began in the fall of 1969 and by the late 1970s the series aired in over 150 domestic and 60 international markets.This helped Star Trek develop a cult following greater than its popularity during its original run.[18]

One sign of the series' growing popularity was the first Star Trek convention which occurred on January 21–23, 1972 in New York City. Although the original estimate of attendees was only a few hundred, several thousand fans turned up. Star Trek fans continue to attend similar conventions worldwide.[19]

The series' newfound success led to the idea of reviving the franchise.[20] Filmation with Paramount Television produced the first post original series show, Star Trek: The Animated Series. It ran on NBC for 22 half-hour episodes over two seasons on Saturday mornings from 1973 to 1974. Although short-lived, typical for animated productions in that time slot during that period, the series garnered the franchise's only "Best Series" Emmy Award as opposed to the franchise's later technical ones. Paramount Pictures and Roddenberry began developing a new series, Star Trek: Phase II, in May 1975 in response to the franchise's newfound popularity. However, work on the series ended when the proposed Paramount Television Service folded.

Following the success of the science fiction movies Star Wars and Close Encounters of the Third Kind, Paramount adapted the planned pilot episode of Phase II into the feature film, Star Trek: The Motion Picture. The film opened in North America on December 7, 1979, with mixed reviews from critics. The film earned $139 million worldwide, below expectations but enough for Paramount to create a sequel. The studio forced Roddenberry to relinquish creative control of future sequels.

The success of the critically acclaimed sequel, Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan, reversed the fortunes of the franchise. While the sequel grossed less than the first movie, The Wrath of Khan 's lower production costs made it net more profit. Paramount produced six Star Trek feature films between 1979 and 1991. In response to the popularity of Star Trek feature films, the franchise returned to television with Star Trek: The Next Generation (TNG) in 1987. Paramount chose to distribute it as a first-run syndication show rather than a network show.[21]

After Roddenberry

Following Star Trek: The Motion Picture, Roddenberry's role was changed from producer to creative consultant with minimal input to the films while being heavily involved with the creation of Star Trek: The Next Generation. Roddenberry died on October 24, 1991, giving executive producer Rick Berman control of the franchise. Star Trek had become known to those within Paramount as "the franchise", because of its great success and recurring role as a tent pole for the studio when other projects failed.[22] TNG had the highest ratings of any Star Trek series and became the #1 syndicated show during the last years of its original seven-season run.[23] In response to TNG's success, Paramount released a spin-off series Deep Space Nine in 1993. While never as popular as TNG, the series had sufficient ratings for it to last seven seasons.In January 1995, a few months after TNG ended, Paramount released a fourth TV series, Voyager. Star Trek saturation reached a peak in the mid-1990s with DS9 and Voyager airing concurrently and three of the four TNG-based feature films released in 1994, 1996, and 1998. By 1998, Star Trek was Paramount's most important property; the enormous profits of "the franchise" funded much of the rest of the studio's operations.[24]:49–50,54 Voyager became the flagship show of the new United Paramount Network (UPN) and thus the first major network Star Trek series since the original.[25]

After Voyager ended, UPN produced Enterprise, a prequel TV series to the original show. Enterprise did not enjoy the high ratings of its predecessors and UPN threatened to cancel it after the series' third season. Fans launched a campaign reminiscent of the one that saved the third season of the Original Series. Paramount renewed Enterprise for a fourth season,[26] but moved it to the Friday night death slot.[27] Like the Original Series, Enterprise ratings dropped during this time slot, and UPN cancelled Enterprise at the end of its fourth season. Enterprise aired its final episode on May 13, 2005.[28] Fan groups, such as "Save Enterprise", attempted to save the series[29] and tried to raise $30 million to privately finance a fifth season of Enterprise.[29] Though the effort garnered considerable press, the fan drive failed to save the series. The cancellation of Enterprise ended an eighteen-year continuous production run of Star Trek programming on television. The poor box office performance in 2002 of the film Nemesis, cast an uncertain light upon the future of the franchise. Paramount relieved Berman, the franchise producer, of control of Star Trek.

Reboot

Paramount turned down several proposals in the mid-2000s to restart the franchise. These included pitches from film director Bryan Singer,[30] Babylon 5 creator J. Michael Straczynski,[31] and Trek actors Jonathan Frakes and William Shatner.[32] The studio also turned down an animated web series.[33] Instead, Paramount hired a new creative team to reinvigorate the franchise in 2007. Writers Roberto Orci and Alex Kurtzman and Lost producer, J. J. Abrams, had the freedom to reinvent the feel of Trek.

The team created the franchise's eleventh film, titled simply Star Trek, releasing it in May 2009. The film featured a new cast portraying the crew of the original Enterprise. Star Trek was a prequel of the original series set in an alternate timeline. This gave the film and future sequels to it freedom from the need to conform to the franchise's canonical timeline. The eleventh Star Trek film's marketing campaign targeted non-fans, even stating in the film's advertisements that "this is not your father's Star Trek".[34]

The film earned considerable critical and financial success, grossing in inflation-adjusted dollars more box office sales than any previous Star Trek film.[35] The plaudits include the franchise's first Academy Award (for makeup). The film's major cast members are contracted for two sequels.[36] Paramount's sequel to the 2009 film, Star Trek Into Darkness, premiered in Sydney, Australia on April 23, 2013, however the movie did not release in the United States until May 17, 2013.[37] While the film was not as successful in the North American box office as its predecessor, internationally, in terms of box office receipts, Into Darkness was the most successful of the franchise.[38] A thirteenth Star Trek film is scheduled to be released on July 8, 2016.[39]

Television series

Six television series make up the bulk of the Star Trek mythos: The Original Series, The Animated Series, The Next Generation, Deep Space Nine, Voyager, and Enterprise. All the different versions in total amount to 726 Star Trek episodes across the 30 seasons of the TV series.[Note 6]The Original Series (1966–69)

William Shatner played the unflappable Captain James T. Kirk in The Original Series, The Animated Series, and seven films, helping to create the standard for all subsequent fictional Starfleet captains.

After three seasons, NBC canceled the show, and the last original episode aired on June 3, 1969.[41] However, the petition near the end of the second season to save the show signed by many Caltech students and its multiple Hugo nominations would indicate that despite low Nielsen ratings, it was highly popular with science fiction fans and engineering students. The series later became popular in reruns and found a cult following.[40]

The Animated Series (1973–74)

Star Trek: The Animated Series, produced by Filmation, ran for two seasons from 1973 to 1974. Most of the original cast performed the voices of their characters from The Original Series, and many of the original series' writers, such as D. C. Fontana, David Gerrold, and Paul Schneider, wrote for the series. While the animated format allowed the producers to create more exotic alien landscapes and life forms, animation errors, and liberal reuse of shots and musical cues have tarnished the series' reputation.[42] Although it was originally sanctioned by Paramount, which owned the Star Trek franchise following its acquisition of Desilu in 1967, Gene Roddenberry often spoke of TAS as non canon.[43] Star Trek writers have used elements of the animated series in later live-action series and movies, and as of June 2007[update], the Animated Series has references in the library section of the official Startrek.com web site.TAS won Star Trek 's first Emmy Award on May 15, 1975.[44] Star Trek TAS briefly returned to television in the mid-1980s on the children's cable network Nickelodeon. Nickelodeon's Evan McGuire greatly admired the show and used its various creative components as inspiration for his short series called Piggly Wiggly Hears A Sound which never aired. Nickelodeon parent Viacom would purchase Paramount in 1994. In the early 1990s, the Sci-Fi Channel also began rerunning TAS. The complete TAS was also released on Laserdisc format during the 1980s.[45] The complete series was first released in the USA on eleven volumes of VHS tapes in 1989. All 22 episodes were released on DVD in 2006.

The Next Generation (1987–1994)

Sir Patrick Stewart, who played Captain Jean-Luc Picard in The Next Generation and subsequent films.

Deep Space Nine (1993–99)

Avery Brooks played Captain Benjamin Sisko in Deep Space Nine, commander of the titular space station and Emissary of the Prophets.

The show begins after the brutal Cardassian occupation of the planet Bajor. The liberated Bajoran people ask the United Federation of Planets to help run a Cardassian built space station, Deep Space Nine, near Bajor. After the Federation takes control of the station, the protagonists of the show discover a uniquely stable wormhole that provides immediate access to the distant Gamma Quadrant making Bajor and the station one of the most strategically important locations in the galaxy.[49] The show chronicles the events of the station's crew, led by Commander (later Captain) Benjamin Sisko, played by Avery Brooks, and Major (later Colonel) Kira Nerys, played by Nana Visitor. Recurring plot elements include the repercussions of the Cardassian occupation of Bajor, Sisko's spiritual role for the Bajorans as the Emissary of the Prophets, and in later seasons a war with the Dominion.

Deep Space Nine stands apart from earlier Trek series for its lengthy serialized storytelling, conflict within the crew, and religious themes—all elements that critics and audiences praised but Roddenberry forbade in the original series and The Next Generation.[50] Nevertheless, he was informed before his death of DS9, making this the last Star Trek series connected to Gene Roddenberry.[51]

Voyager (1995–2001)

Kate Mulgrew, who played Captain Kathryn Janeway, the lead character in Voyager, and the first female commanding officer in a leading role of a Star Trek series.

Enterprise (2001–05)

Science fiction veteran Scott Bakula played Captain Jonathan Archer, the lead character in Enterprise, a prequel to the original show.

During the show's first two seasons, Enterprise featured self-contained episodes, like The Original Series, The Next Generation and Voyager. The third season consisted of one arc, "Xindi mission", which had the darker tone and serialized nature of Deep Space 9. Season 4 consisted of several two to three episode mini-arcs. The final season showed the origins of elements seen in earlier series, and it rectified and resolved some core continuity problems between the various Star Trek series. Ratings for Enterprise started strong but declined rapidly. Although critics received the fourth season well, both fans and the cast reviled the series finale, partly because of the episode's focus on the guest appearance of members of The Next Generation cast.[55] The cancellation of Enterprise ended an 18-year run of back-to-back new Star Trek shows beginning with The Next Generation in 1987.

Feature films

Paramount Pictures has produced twelve Star Trek feature films, the most recent being released in May 2013.[56] The first six films continue the adventures of the cast of The Original Series; the seventh film, Generations was designed as a transition from that cast to The Next Generation television series; the next three films, 8–10, focused completely on the Next Generation cast.[Note 8] The eleventh and twelfth films take place in an alternate timeline from rest of the franchise set with a new cast playing the original series characters, and with Leonard Nimoy as an elderly Spock providing a physical link to the original timeline.| Title | U.S. release date | Director |

|---|---|---|

| The Original Series | ||

| Star Trek: The Motion Picture | December 7, 1979 | Robert Wise |

| Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan | June 4, 1982 | Nicholas Meyer |

| Star Trek III: The Search for Spock | June 1, 1984 | Leonard Nimoy |

| Star Trek IV: The Voyage Home | November 26, 1986 | |

| Star Trek V: The Final Frontier | June 9, 1989 | William Shatner |

| Star Trek VI: The Undiscovered Country | December 6, 1991 | Nicholas Meyer |

| The Next Generation[Note 9] | ||

| Star Trek Generations | November 18, 1994 | David Carson |

| Star Trek: First Contact | November 22, 1996 | Jonathan Frakes |

| Star Trek: Insurrection | December 11, 1998 | |

| Star Trek: Nemesis | December 13, 2002 | Stuart Baird |

| Reboot[Note 3] | ||

| Star Trek | May 8, 2009[Note 10] | J. J. Abrams |

| Star Trek Into Darkness | May 16, 2013[Note 11] | |

| Untitled Star Trek Sequel | July 8, 2016[39] | Justin Lin[39] |

Merchandise

Many licensed products are based on the Star Trek franchise. Merchandising is very lucrative for both studio and actors; by 1986 Nimoy had earned more than $500,000 from royalties.[57] Products include novels, comic books, video games, and other materials, which are generally considered non-canon.Books

Since 1967, hundreds of original novels, short stories, and television and movie adaptations have been published. The first original Star Trek novel was Mission to Horatius by Mack Reynolds, which was published in hardcover by Whitman Books in 1968.The first publisher of Star Trek fiction aimed at adult readers was Bantam Books. In 1970, James Blish wrote the first original Star Trek novel published by Bantam, Spock Must Die!. Pocket Books is the publisher of Star Trek novels.

Prolific Star Trek novelists include Peter David, Diane Carey, Keith R. A. DeCandido, J. M. Dillard, Diane Duane, Michael Jan Friedman, and Judith and Garfield Reeves-Stevens. Several actors and writers from the television series have also written books: William Shatner, and John de Lancie, Andrew J. Robinson, J. G. Hertzler, and Armin Shimerman have written or co-written books featuring their respective characters. Voyager producer Jeri Taylor wrote two novels featuring back story for Voyager characters, and screen authors David Gerrold, D. C. Fontana, and Melinda Snodgrass have penned books, as well.

A scholarly book published by Springer Science+Business Media in 2014 discusses the actualization of Star Trek's holodeck in the future by making extensive use of artificial intelligence and cyborgs.[58]

Comics

Star Trek-based comics have been published almost continuously since 1967 by several companies including: Marvel, DC, Malibu, Wildstorm, and Gold Key. Tokyopop is publishing an anthology of Next Generation-based stories presented in the style of Japanese manga.[59] As of 2006[update], IDW Publishing secured publishing rights to Star Trek comics[60] and published a prequel to the 2009 film, Star Trek: Countdown. In 2012 they published Volume I of Star Trek – The Newspaper Strip featuring the work of Thomas Warkentin.[61]Games

The Star Trek franchise has numerous games in many formats. Beginning in 1967 with a board game based on the original series and continuing through today with online and DVD games, Star Trek games continue to be popular among fans.Video games of the series include Star Trek: Legacy and Star Trek: Conquest. An MMORPG based on Star Trek called Star Trek Online was developed by Cryptic Studios and published by Perfect World. It is set in the TNG universe about 30 years after the events of Star Trek: Nemesis.[62] The most recent video game, set in the new timeline debuted in J. J. Abrams's film, was titled Star Trek.

On June 8, 2010, Wiz Kids Games, which is owned by NECA, announced that they are developing a Star Trek collectible miniatures game using the HeroClix game system.[63]

Magazines

Star Trek has led directly or indirectly to the creation of a number of magazines which focus either on science fiction or specifically on Star Trek. Starlog was a magazine which was founded in the 1970s. Initially, its focus was on Star Trek actors, but then it began to expand its scope.In 2013, Star Trek Magazine was a significant publication from the U.K. which was sold at newsstands and also via subscription. Other magazines through the years included professional magazines as well as magazines produced by fans, referred to as "fanzines". Star Trek: The Magazine was a magazine published in the U.S. which ceased publication in 2003.

Cultural impact

Prototype space shuttle Enterprise named after the fictional starship with Star Trek television cast members and creator Gene Roddenberry.

The Star Trek media franchise is a multi-billion dollar industry, owned by CBS.[64] Gene Roddenberry sold Star Trek to NBC as a classic adventure drama; he pitched the show as "Wagon Train to the Stars" and as Horatio Hornblower in Space.[65] The opening line, "to boldly go where no man has gone before," was taken almost verbatim from a US White House booklet on space produced after the Sputnik flight in 1957.[66] The central trio of Kirk, Spock, and McCoy was modeled on classical mythological storytelling.[65]

Star Trek and its spin-offs have proven highly popular in syndication and are shown on TV stations worldwide.[67] The show's cultural impact goes far beyond its longevity and profitability. Star Trek conventions have become popular among its fans, who call themselves "trekkies" or "trekkers". An entire subculture has grown up around the show[68] which was documented in the film Trekkies. Star Trek was the highest-ranked cult show by TV Guide.[69] The franchise has also garnered many comparisons of the Star Wars franchise being rivals in the science fiction genre with many fans and scholars.[70][71][72]

The Star Trek franchise inspired some designers of technologies, such as the Palm PDA and the handheld mobile phone.[73][74] Michael Jones, Chief technologist of Google Earth, has cited the tricorder's mapping capability as one inspiration in the development of Keyhole/Google Earth.[75] The Tricorder X PRIZE, a contest to build a medical tricorder device was announced in 2012. Ten finalists have been selected in 2014, and the winner will be selected in January 2016. Star Trek also brought teleportation to popular attention with its depiction of "matter-energy transport", with the famously misquoted phrase "Beam me up, Scotty" entering the vernacular.[76] In 1976, following a letter-writing campaign, NASA named its prototype space shuttle Enterprise, after the fictional starship.[77] Later, the introductory sequence to Star Trek: Enterprise included footage of this shuttle which, along with images of a naval sailing vessel called the Enterprise, depicted the advancement of human transportation technology.

Beyond Star Trek's fictional innovations, its contributions to TV history included a multicultural and multiracial cast. While more common in subsequent years, in the 1960s it was controversial to feature an Enterprise crew that included a Japanese helmsman, a Russian navigator, a black female communications officer, and a Vulcan-Human first officer. Captain Kirk's and Lt. Uhura's kiss, in the episode "Plato's Stepchildren", was also daring, and is often mis-cited as being American television's first scripted, interracial kiss, even though several other interracial kisses predated this one.[78]

Parodies

Early TV comedy sketch parodies of Star Trek included a famous sketch on Saturday Night Live titled "The Last Voyage of the Starship Enterprise", with John Belushi as Kirk, Chevy Chase as Spock and Dan Aykroyd as McCoy.[79] In the 1980s, Saturday Night Live did a sketch with William Shatner reprising his Captain Kirk role in The Restaurant Enterprise, preceded by a sketch in which he played himself at a Trek convention angrily telling fans to "Get a Life", a phrase that has become part of Trek folklore.[80] In Living Color continued the tradition in a sketch where Captain Kirk is played by a fellow Canadian Jim Carrey.[81]A feature-length film that indirectly parodies Star Trek is Galaxy Quest. This film is based on the premise that aliens monitoring the broadcast of an Earth-based TV series called Galaxy Quest, modeled heavily on Star Trek, believe that what they are seeing is real.[82] Many Star Trek actors have been quoted saying that Galaxy Quest was a brilliant parody.[83][84]

Star Trek has been blended with Gilbert and Sullivan at least twice. The North Toronto Players presented a Star Trek adaptation of Gilbert & Sullivan titled H.M.S. Starship Pinafore: The Next Generation in 1991 and an adaptation by Jon Mullich of Gilbert & Sullivan's H.M.S. Pinafore that sets the operetta in the world of Star Trek has played in Los Angeles and was attended by series luminaries Nichelle Nichols,[citation needed] D.C. Fontana and David Gerrold.[85] A similar blend of Gilbert and Sullivan and Star Trek was presented as a benefit concert in San Francisco by the Lamplighters in 2009. The show was titled Star Drek: The Generation After That. It presented an original story with Gilbert and Sullivan melodies.[86]

Both The Simpsons and Futurama television series and others have had many individual episodes parodying Star Trek or with Trek allusions.[87] An entire series of films and novels from Finland titled Star Wreck also parodies Star Trek.[citation needed]

Star Trek has been parodied in several non-English movies, including the German Traumschiff Surprise - Periode 1 which features a gay version of The Original Series bridge crew and a Turkish film that spoofs that same series' episode "The Man Trap" in one of the series of films based on the character Turist Ömer.[citation needed]

Notable fan fiction

Although Star Trek has been off the air since 2005, CBS and Paramount pictures have allowed fan-produced shows to be created. While not officially part of the Star Trek universe, several veteran Star Trek actors, actresses, and writers have contributed their talents to these many of these productions. While none of these films have been created for profit, several fan productions have turned to crowdfunding from sites such as Kickstarter to help with production costs.[88]Two series set during the TOS time period are Star Trek Continues and the Hugo award nominated Star Trek: Phase II. Another series, Star Trek Hidden Frontier, takes place on the Briar Patch, a region of space introduced in Star Trek Insurrection. It has had over 50 episodes produced, and has two spin-off series, Star Trek: Odyssey and Star Trek: The Helena Chronicles. Several standalone fan films have been created including Star Trek: Of Gods and Men. Future fan films include, Star Trek: Axanar and Star Trek: Renegades.[89] Audio only fan productions includes Star Trek: The Continuing Mission. Several fan film parodies have also been created.

Awards and honors

Of the various science fiction awards for drama, only the Hugo Award dates back as far as the original series.[Note 12] In 1968, all five nominees for a Hugo Award were individual episodes of Star Trek, as were three of the five nominees in 1967.[Note 13] The only Star Trek series to not get even a Hugo nomination are the animated series and Voyager, though only the original series and Next Generation ever won the award. No Star Trek featured film has ever won a Hugo, though a few were nominated. In 2008, the fan made episode of Star Trek: New Voyages entitled "World Enough and Time" was nominated for the Hugo for Best Short Drama.[90]The two Star Trek series to win multiple Saturn awards during their run were The Next Generation (twice winning for best television series) and Voyager (twice winning for best actress – Kate Mulgrew and Jeri Ryan).[Note 14] The original series retroactively won a Saturn Award for best DVD release. Several Star Trek films have won Saturns including categories such as best actor, actress, director, costume design, and special effects. However, Star Trek has never won a Saturn for best make-up.[91]

As for non science fiction specific awards, the Star Trek series has won 31 Emmy Awards.[92] The eleventh Star Trek film won the 2009 Academy Award for Best Makeup, the franchise's first Academy Award.[93]

Corporate ownership

At Star Trek 's creation, Norway Productions, Roddenberry's production company, shared ownership with Desilu Productions and, after Gulf+Western acquired Desilu in 1967, with Paramount Pictures, the conglomerate's film studio. Paramount did not want to own the unsuccessful show; net profit was to be shared between Norway, Desilu/Paramount, Shatner, and NBC but Star Trek lost money, and the studio did not expect to syndicate it. In 1970 Paramount offered to sell all rights to Star Trek to Roddenberry, but he could not afford the $150,000 ($911,000 today) price.[12]In 1989, Gulf+Western renamed itself as Paramount Communications, and in 1994 merged with Viacom.[12] In 2005, Viacom divided into CBS Corporation, whose CBS Television Studios subsidiary retained the Star Trek brand, and Viacom, whose Paramount Pictures subsidiary retained the Star Trek film library and rights to make additional films, along with video distribution rights to the TV series on behalf of CBS.[94][12]