While a novel device is often described as an innovation, in economics, management science,

and other fields of practice and analysis, innovation is generally

considered to be the result of a process that brings together various

novel ideas in such a way that they affect society. In industrial economics, innovations are created and found empirically from services to meet growing consumer demand.

Innovation also has an older historical meaning which is quite different. From the 1400s through the 1600s, prior to early American settlement, the concept of "innovation" was pejorative. It was an early modern synonym for rebellion, revolt and heresy.

Innovation also has an older historical meaning which is quite different. From the 1400s through the 1600s, prior to early American settlement, the concept of "innovation" was pejorative. It was an early modern synonym for rebellion, revolt and heresy.

Definition

A 2014 survey of literature on innovation found over 40 definitions. In an industrial survey of how the software industry

defined innovation, the following definition given by Crossan and

Apaydin was considered to be the most complete, which builds on the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) manual's definition:

Innovation is production or adoption, assimilation, and exploitation of a value-added novelty in economic and social spheres; renewal and enlargement of products, services, and markets; development of new methods of production; and the establishment of new management systems. It is both a process and an outcome.

According to Kanter innovation includes original invention and

creative use and defines innovation as a generation, admission and

realization of new ideas, products, services and processes.

Two main dimensions of innovation were degree of novelty (patent)

(i.e. whether an innovation is new to the firm, new to the market, new

to the industry, or new to the world) and kind of innovation (i.e.

whether it is processor product-service system innovation).

In recent organizational scholarship, researchers of workplaces have

also distinguished innovation to be separate from creativity, by

providing an updated definition of these two related but distinct

constructs:

Workplace creativity concerns the cognitive and behavioral processes applied when attempting to generate novel ideas. Workplace innovation concerns the processes applied when attempting to implement new ideas. Specifically, innovation involves some combination of problem/opportunity identification, the introduction, adoption or modification of new ideas germane to organizational needs, the promotion of these ideas, and the practical implementation of these ideas.

Inter-disciplinary views

Business and economics

In business and in economics, innovation can become a catalyst for growth. With rapid advancements in transportation and communications over the past few decades, the old-world concepts of factor endowments and comparative advantage which focused on an area's unique inputs are outmoded for today's global economy. Economist Joseph Schumpeter (1883–1950), who contributed greatly to the study of innovation economics,

argued that industries must incessantly revolutionize the economic

structure from within, that is innovate with better or more effective

processes and products, as well as market distribution, such as the

connection from the craft shop to factory. He famously asserted that "creative destruction is the essential fact about capitalism". Entrepreneurs continuously look for better ways to satisfy their consumer base

with improved quality, durability, service and price which come to

fruition in innovation with advanced technologies and organizational

strategies.

A prime example of innovation involved the explosive boom of Silicon Valley startups out of the Stanford Industrial Park. In 1957, dissatisfied employees of Shockley Semiconductor, the company of Nobel laureate and co-inventor of the transistor William Shockley, left to form an independent firm, Fairchild Semiconductor.

After several years, Fairchild developed into a formidable presence in

the sector. Eventually, these founders left to start their own companies

based on their own, unique, latest ideas, and then leading employees

started their own firms. Over the next 20 years, this snowball process

launched the momentous startup-company explosion of information-technology firms. Essentially, Silicon Valley began as 65 new enterprises born out of Shockley's eight former employees. Since then, hubs of innovation have sprung up globally with similar metonyms, including Silicon Alley encompassing New York City.

Another example involves business incubators

– a phenomenon nurtured by governments around the world, close to

knowledge clusters (mostly research-based) like universities or other Government Excellence Centres – which aim primarily to channel generated knowledge to applied innovation outcomes in order to stimulate regional or national economic growth.

Organizations

In the organizational context, innovation may be linked to positive changes in efficiency, productivity, quality, competitiveness, and market share.

However, recent research findings highlight the complementary role of

organizational culture in enabling organizations to translate innovative

activity into tangible performance improvements.

Organizations can also improve profits and performance by providing

work groups opportunities and resources to innovate, in addition to

employee's core job tasks. Peter Drucker wrote:

Innovation is the specific function of entrepreneurship, whether in an existing business, a public service institution, or a new venture started by a lone individual in the family kitchen. It is the means by which the entrepreneur either creates new wealth-producing resources or endows existing resources with enhanced potential for creating wealth. –Drucker

According to Clayton Christensen, disruptive innovation is the key to future success in business.

The organisation requires a proper structure in order to retain

competitive advantage. It is necessary to create and nurture an

environment of innovation. Executives and managers need to break away

from traditional ways of thinking and use change to their advantage. It

is a time of risk but even greater opportunity.

The world of work is changing with the increase in the use of

technology and both companies and businesses are becoming increasingly

competitive. Companies will have to downsize and re-engineer their

operations to remain competitive. This will affect employment as

businesses will be forced to reduce the number of people employed while

accomplishing the same amount of work if not more.

While disruptive innovation will typically "attack a traditional

business model with a lower-cost solution and overtake incumbent firms

quickly,"

foundational innovation is slower, and typically has the potential to

create new foundations for global technology systems over the longer

term. Foundational innovation tends to transform business operating models as entirely new business models emerge over many years, with gradual and steady adoption of the innovation leading to waves of technological and institutional change that gain momentum more slowly. The advent of the packet-switched communication protocol TCP/IP—originally introduced in 1972 to support a single use case for United States Department of Defense electronic communication (email), and which gained widespread adoption only in the mid-1990s with the advent of the World Wide Web—is a foundational technology.

All organizations can innovate, including for example hospitals, universities, and local governments. For instance, former Mayor Martin O’Malley pushed the City of Baltimore to use CitiStat, a performance-measurement

data and management system that allows city officials to maintain

statistics on several areas from crime trends to the conditions of potholes.

This system aids in better evaluation of policies and procedures with

accountability and efficiency in terms of time and money. In its first

year, CitiStat saved the city $13.2 million. Even mass transit systems have innovated with hybrid bus fleets to real-time tracking at bus stands. In addition, the growing use of mobile data terminals

in vehicles, that serve as communication hubs between vehicles and a

control center, automatically send data on location, passenger counts,

engine performance, mileage and other information. This tool helps to

deliver and manage transportation systems.

Still other innovative strategies include hospitals digitizing medical information in electronic medical records. For example, the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development's HOPE VI initiatives turned severely distressed public housing in urban areas into revitalized, mixed-income environments; the Harlem Children’s Zone used a community-based approach to educate local area children; and the Environmental Protection Agency's brownfield grants facilitates turning over brownfields for environmental protection, green spaces, community and commercial development.

Hasmath et al. have found that within local government

organizations in China, the appetite to innovate may be linked to

specific character types. They identify three distinct character types

within the Chinese local government: authoritarian bureaucratic, a

primarily older male cadre who are most likely to follow central

government command; a consultative governance types that is most open to

collaborating with NGOs and outside of government, and; an

entrepreneurial type that is both less risk averse and demonstrates high

personal efficacy.

Sources

There

are several sources of innovation. It can occur as a result of a focus

effort by a range of different agents, by chance, or as a result of a

major system failure.

According to Peter F. Drucker,

the general sources of innovations are different changes in industry

structure, in market structure, in local and global demographics, in

human perception, mood and meaning, in the amount of already available

scientific knowledge, etc.

Original model of three phases of the process of Technological Change

In the simplest linear model of innovation the traditionally recognized source is manufacturer innovation.

This is where an agent (person or business) innovates in order to sell

the innovation. Specifically, R&D measurement is the commonly used

input for innovation, in particular in the business sector, named

Business Expenditure on R&D (BERD) that grew over the years on the

expenses of the declining R&D invested by the public sector.

Another source of innovation, only now becoming widely recognized, is end-user innovation.

This is where an agent (person or company) develops an innovation for

their own (personal or in-house) use because existing products do not

meet their needs. MIT economist Eric von Hippel has identified end-user innovation as, by far, the most important and critical in his classic book on the subject, The Sources of Innovation.

The robotics engineer Joseph F. Engelberger asserts that innovations require only three things:

- A recognized need,

- Competent people with relevant technology, and

- Financial support.

However, innovation processes usually involve: identifying customer

needs, macro and meso trends, developing competences, and finding

financial support.

The Kline chain-linked model of innovation

places emphasis on potential market needs as drivers of the innovation

process, and describes the complex and often iterative feedback loops

between marketing, design, manufacturing, and R&D.

Innovation by businesses is achieved in many ways, with much attention now given to formal research and development

(R&D) for "breakthrough innovations". R&D help spur on patents

and other scientific innovations that leads to productive growth in such

areas as industry, medicine, engineering, and government.

Yet, innovations can be developed by less formal on-the-job

modifications of practice, through exchange and combination of

professional experience and by many other routes. Investigation of

relationship between the concepts of innovation and technology transfer

revealed overlap.

The more radical and revolutionary innovations tend to emerge from

R&D, while more incremental innovations may emerge from practice –

but there are many exceptions to each of these trends.

Information technology and changing business processes and management style can produce a work climate favorable to innovation. For example, the software tool company Atlassian conducts quarterly "ShipIt Days" in which employees may work on anything related to the company's products. Google employees work on self-directed projects for 20% of their time (known as Innovation Time Off). Both companies cite these bottom-up processes as major sources for new products and features.

An important innovation factor includes customers buying products

or using services. As a result, firms may incorporate users in focus groups (user centred approach), work closely with so called lead users

(lead user approach) or users might adapt their products themselves.

The lead user method focuses on idea generation based on leading users

to develop breakthrough innovations. U-STIR, a project to innovate Europe’s surface transportation system, employs such workshops. Regarding this user innovation,

a great deal of innovation is done by those actually implementing and

using technologies and products as part of their normal activities.

Sometimes user-innovators may become entrepreneurs,

selling their product, they may choose to trade their innovation in

exchange for other innovations, or they may be adopted by their

suppliers. Nowadays, they may also choose to freely reveal their

innovations, using methods like open source.

In such networks of innovation the users or communities of users can

further develop technologies and reinvent their social meaning.

One technique for innovating a solution to an identified problem

is to actually attempt an experiment with many possible solutions. This technique was famously used by Thomas Edison's laboratory to find a version of the incandescent light bulb economically viable for home use, which involved searching through thousands of possible filament designs before settling on carbonized bamboo.

This technique is sometimes used in pharmaceutical drug discovery. Thousands of chemical compounds are subjected to high-throughput screening

to see if they have any activity against a target molecule which has

been identified as biologically significant to a disease. Promising

compounds can then be studied; modified to improve efficacy, reduce side

effects, and reduce cost of manufacture; and if successful turned into

treatments.

The related technique of A/B testing is often used to help optimize the design of web sites and mobile apps. This is used by major sites such as amazon.com, Facebook, Google, and Netflix. Procter & Gamble

uses computer-simulated products and online user panels to conduct

larger numbers of experiments to guide the design, packaging, and shelf

placement of consumer products. Capital One uses this technique to drive credit card marketing offers.

Goals and failures

Programs of organizational innovation are typically tightly linked to organizational goals and objectives, to the business plan, and to market competitive positioning.

One driver for innovation programs in corporations is to achieve growth

objectives. As Davila et al. (2006) notes, "Companies cannot grow

through cost reduction and reengineering alone... Innovation is the key

element in providing aggressive top-line growth, and for increasing

bottom-line results".

One survey across a large number of manufacturing and services

organizations found, ranked in decreasing order of popularity, that

systematic programs of organizational innovation are most frequently

driven by: improved quality, creation of new markets, extension of the product range, reduced labor costs, improved production processes, reduced materials, reduced environmental damage, replacement of products/services, reduced energy consumption, conformance to regulations.

These goals vary between improvements to products, processes and

services and dispel a popular myth that innovation deals mainly with new

product development. Most of the goals could apply to any organisation

be it a manufacturing facility, marketing firm, hospital or local

government. Whether innovation goals are successfully achieved or

otherwise depends greatly on the environment prevailing in the firm.

Conversely, failure can develop in programs of innovations. The

causes of failure have been widely researched and can vary considerably.

Some causes will be external to the organization and outside its

influence of control. Others will be internal and ultimately within the

control of the organization. Internal causes of failure can be divided

into causes associated with the cultural infrastructure and causes

associated with the innovation process itself. Common causes of failure

within the innovation process in most organizations can be distilled

into five types: poor goal definition, poor alignment of actions to

goals, poor participation in teams, poor monitoring of results, poor

communication and access to information.

Diffusion

Diffusion of innovation research was first started in 1903 by seminal researcher Gabriel Tarde, who first plotted the S-shaped diffusion curve. Tarde defined the innovation-decision process as a series of steps that includes:

- First knowledge

- Forming an attitude

- A decision to adopt or reject

- Implementation and use

- Confirmation of the decision

Once innovation occurs, innovations may be spread from the innovator

to other individuals and groups. This process has been proposed that the

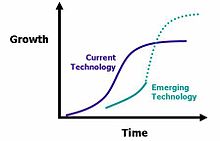

life cycle of innovations can be described using the 's-curve' or diffusion curve.

The s-curve maps growth of revenue or productivity against time. In the

early stage of a particular innovation, growth is relatively slow as

the new product establishes itself. At some point, customers begin to

demand and the product growth increases more rapidly. New incremental

innovations or changes to the product allow growth to continue. Towards

the end of its lifecycle, growth slows and may even begin to decline. In

the later stages, no amount of new investment in that product will

yield a normal rate of return.

The s-curve derives from an assumption that new products are

likely to have "product life" – i.e., a start-up phase, a rapid increase

in revenue and eventual decline. In fact, the great majority of

innovations never get off the bottom of the curve, and never produce

normal returns.

Innovative companies will typically be working on new innovations

that will eventually replace older ones. Successive s-curves will come

along to replace older ones and continue to drive growth upwards. In the

figure above the first curve shows a current technology. The second

shows an emerging technology

that currently yields lower growth but will eventually overtake current

technology and lead to even greater levels of growth. The length of

life will depend on many factors.

Measures

Measuring

innovation is inherently difficult as it implies commensurability so

that comparisons can be made in quantitative terms. Innovation, however,

is by definition novelty. Comparisons are thus often meaningless across

products or service. Nevertheless, Edison et al. in their review of literature on innovation management

found 232 innovation metrics. They categorized these measures along

five dimensions i.e. inputs to the innovation process, output from the

innovation process, effect of the innovation output, measures to access

the activities in an innovation process and availability of factors that

facilitate such a process.

There are two different types of measures for innovation: the organizational level and the political level.

Organizational level

The

measure of innovation at the organizational level relates to

individuals, team-level assessments, and private companies from the

smallest to the largest company. Measure of innovation for organizations

can be conducted by surveys, workshops, consultants, or internal

benchmarking. There is today no established general way to measure

organizational innovation. Corporate measurements are generally

structured around balanced scorecards

which cover several aspects of innovation such as business measures

related to finances, innovation process efficiency, employees'

contribution and motivation, as well benefits for customers. Measured

values will vary widely between businesses, covering for example new

product revenue, spending in R&D, time to market, customer and

employee perception & satisfaction, number of patents, additional

sales resulting from past innovations.

Political level

For the political level, measures of innovation are more focused on a country or region competitive advantage

through innovation. In this context, organizational capabilities can be

evaluated through various evaluation frameworks, such as those of the

European Foundation for Quality Management. The OECD

Oslo Manual (1995) suggests standard guidelines on measuring

technological product and process innovation. Some people consider the Oslo Manual complementary to the Frascati Manual

from 1963. The new Oslo manual from 2005 takes a wider perspective to

innovation, and includes marketing and organizational innovation. These

standards are used for example in the European Community Innovation Surveys.

Other ways of measuring innovation have traditionally been

expenditure, for example, investment in R&D (Research and

Development) as percentage of GNP (Gross National Product). Whether this

is a good measurement of innovation has been widely discussed and the

Oslo Manual has incorporated some of the critique against earlier

methods of measuring. The traditional methods of measuring still inform

many policy decisions. The EU Lisbon Strategy has set as a goal that their average expenditure on R&D should be 3% of GDP.

Indicators

Many

scholars claim that there is a great bias towards the "science and

technology mode" (S&T-mode or STI-mode), while the "learning by

doing, using and interacting mode" (DUI-mode) is ignored and

measurements and research about it rarely done. For example, an

institution may be high tech with the latest equipment, but lacks

crucial doing, using and interacting tasks important for innovation.

A common industry view (unsupported by empirical evidence) is that comparative cost-effectiveness research is a form of price control

which reduces returns to industry, and thus limits R&D expenditure,

stifles future innovation and compromises new products access to

markets.

Some academics claim cost-effectiveness research is a valuable

value-based measure of innovation which accords "truly significant"

therapeutic advances (i.e. providing "health gain") higher prices than

free market mechanisms. Such value-based pricing has been viewed as a means of indicating to industry the type of innovation that should be rewarded from the public purse.

An Australian academic developed the case that national comparative cost-effectiveness analysis systems should be viewed as measuring "health innovation" as an evidence-based policy concept for valuing innovation distinct from valuing through competitive markets, a method which requires strong anti-trust laws to be effective, on the basis that both methods of assessing pharmaceutical innovations are mentioned in annex 2C.1 of the Australia-United States Free Trade Agreement.

Indices

Several indices attempt to measure innovation and rank entities based on these measures, such as:

- The Bloomberg Innovation Index

- The "Bogota Manual" similar to the Oslo Manual, is focused on Latin America and the Caribbean countries.

- The "Creative Class" developed by Richard Florida

- The EIU Innovation Ranking

- The Global Competitiveness Report

- The Global Innovation Index (GII), by INSEAD

- The Information Technology and Innovation Foundation (ITIF) Index

- Innovation 360 – From the World Bank. Aggregates innovation indicators (and more) from a number of different public sources

- The Innovation Capacity Index (ICI) published by a large number of international professors working in a collaborative fashion. The top scorers of ICI 2009–2010 were: 1. Sweden 82.2; 2. Finland 77.8; and 3. United States 77.5.

- The Innovation Index, developed by the Indiana Business Research Center, to measure innovation capacity at the county or regional level in the United States.

- The Innovation Union Scoreboard

- The innovationsindikator for Germany, developed by the Federation of German Industries (Bundesverband der Deutschen Industrie) in 2005

- The INSEAD Innovation Efficacy Index

- The International Innovation Index, produced jointly by The Boston Consulting Group, the National Association of Manufacturers and its nonpartisan research affiliate The Manufacturing Institute, is a worldwide index measuring the level of innovation in a country. NAM describes it as the "largest and most comprehensive global index of its kind".

- The Management Innovation Index – Model for Managing Intangibility of Organizational Creativity: Management Innovation Index

- The NYCEDC Innovation Index, by the New York City Economic Development Corporation, tracks New York City's "transformation into a center for high-tech innovation. It measures innovation in the City's growing science and technology industries and is designed to capture the effect of innovation on the City's economy."

- The Oslo Manual is focused on North America, Europe, and other rich economies.

- The State Technology and Science Index, developed by the Milken Institute, is a U.S.-wide benchmark to measure the science and technology capabilities that furnish high paying jobs based around key components.

- The World Competitiveness Scoreboard

Rankings

Many research studies try to rank countries based on measures of innovation. Common areas of focus include: high-tech companies, manufacturing, patents, post secondary education, research and development, and research personnel. The left ranking of the top 10 countries below is based on the 2016 Bloomberg Innovation Index. However, studies may vary widely; for example the Global Innovation Index 2016 ranks Switzerland as number one wherein countries like South Korea and Japan do not even make the top ten.

|

|

Future

In 2005 Jonathan Huebner, a physicist working at the Pentagon's Naval Air Warfare Center, argued on the basis of both U.S. patents

and world technological breakthroughs, per capita, that the rate of

human technological innovation peaked in 1873 and has been slowing ever

since. In his article, he asked "Will the level of technology reach a maximum and then decline as in the Dark Ages?" In later comments to New Scientist magazine, Huebner clarified that while he believed that we will reach a rate of innovation in 2024 equivalent to that of the Dark Ages, he was not predicting the reoccurrence of the Dark Ages themselves.

John Smart criticized the claim and asserted that technological singularity researcher Ray Kurzweil and others showed a "clear trend of acceleration, not deceleration" when it came to innovations. The foundation replied to Huebner the journal his article was published in, citing Second Life and eHarmony as proof of accelerating innovation; to which Huebner replied.

However, Huebner's findings were confirmed in 2010 with U.S. Patent Office data. and in a 2012 paper.

Innovation and development

The theme of innovation as a tool to disrupting patterns of poverty has gained momentum since the mid-2000s among major international development actors such as DFID, Gates Foundation's use of the Grand Challenge funding model, and USAID's Global Development Lab. Networks have been established to support innovation in development, such as D-Lab at MIT. Investment funds have been established to identify and catalyze innovations in developing countries, such as DFID's Global Innovation Fund, Human Development Innovation Fund, and (in partnership with USAID) the Global Development Innovation Ventures.

Government policies

Given the noticeable effects on efficiency, quality of life, and productive growth,

innovation is a key factor in society and economy. Consequently,

policymakers have long worked to develop environments that will foster

innovation and its resulting positive benefits, from funding Research and Development

to supporting regulatory change, funding the development of innovation

clusters, and using public purchasing and standardisation to 'pull'

innovation through.

For instance, experts are advocating that the U.S. federal

government launch a National Infrastructure Foundation, a nimble,

collaborative strategic intervention organization that will house

innovations programs from fragmented silos under one entity, inform

federal officials on innovation performance metrics, strengthen industry-university partnerships, and support innovation economic development initiatives, especially to strengthen regional clusters.

Because clusters are the geographic incubators of innovative products

and processes, a cluster development grant program would also be

targeted for implementation. By focusing on innovating in such areas as

precision manufacturing, information technology, and clean energy, other areas of national concern would be tackled including government debt, carbon footprint, and oil dependence. The U.S. Economic Development Administration understand this reality in their continued Regional Innovation Clusters initiative.

In addition, federal grants in R&D, a crucial driver of innovation

and productive growth, should be expanded to levels similar to Japan, Finland, South Korea, and Switzerland in order to stay globally competitive. Also, such grants should be better procured to metropolitan areas, the essential engines of the American economy.

Many countries recognize the importance of research and development as well as innovation including Japan's Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT); Germany's Federal Ministry of Education and Research; and the Ministry of Science and Technology in the People's Republic of China. Furthermore, Russia's innovation programme is the Medvedev modernisation programme which aims at creating a diversified economy based on high technology and innovation. Also, the Government of Western Australia has established a number of innovation incentives for government departments. Landgate was the first Western Australian government agency to establish its Innovation Program.

Regions have taken a more proactive role in supporting innovation. Many regional governments are setting up regional innovation agency to strengthen regional innovation capabilities. In Medellin, Colombia, the municipality of Medellin created in 2009 Ruta N to transform the city into a knowledge city.