Stylised atom as an emblem of science.

An emblem of the Theosophical Society.

Immediately after formation the Theosophical Society in 1875, the founders of modern Theosophy were aimed to show that their ideas can be confirmed by science. According to professor Olav Hammer,

at the end of the 19th century the Theosophical doctrine has acquired

in Europe and America wide popularity, thanking to numerous

publications, which contained its simplified exposition and, in

particular, asserted that Theosophy "includes" both science and

religion, thus, positioning itself as "a scientific religion," or "a

religious science." Professor Joscelyn Godwin wrote that the Theosophical Society was formed at the "crucial historical moment when it seemed possible to unite science and occultism, West and East" in modern Theosophy, adding into Western civilization the esoteric Eastern wisdom.

Scientism of Theosophy

For

the modern Theosophy, which Hammer considered as a standard of the

esoteric tradition, conventional science is called upon to play "two

diametrically opposite roles." On the one hand, Theosophy has always

expressed its clearly negative attitude towards it. On the other hand,

in the process of building the occult doctrine, it gave to certain

fragments of scientific discourse the status of valued elements. In this

case, science was not used as an object of criticism, but as "a basis

of legitimacy and source of doctrinal elements." Thus, in Hammer's

opinion, the main goal was achieved: the doctrine acquired a

"scientistic" appearance.

The Theosophical Society proclaimed its third main task, "To

investigate the unexplained laws of nature and the powers latent in

man."

Thus, it set itself one of its goals to investigate phenomena whose

existence itself is highly controversial, that is, the very premises of

Theosophy have become "fertile ground" for the search for "scientistic

formulations." Scientism and the ambivalence relation to science were

already evident in the first Theosophical publications. It can be seen

in both Blavatsky's early articles, and in Isis Unveiled,

the book that became the "first full-scale attempt" to create the

Theosophical doctrine, where she stated that Theosophy does not

contradict science, but is, in fact, a "higher form of science", in

comparison with what is usually understood by this term. This statement by Blavatsky is quoted in Hammer's thesis:

The exercise of magical power is the exercise of natural powers, but superior to the ordinary functions of Nature. A miracle is not a violation of the laws of Nature, except for ignorant people. Magic is but a science, a profound knowledge of the Occult forces in Nature, and of the laws governing the visible or the invisible world... A powerful mesmerizer, profoundly learned in his science, such as Baron du Potet, Regazzoni, Pietro d'Amicis of Bologna, are magicians, for they have become the adepts, the initiated ones, into the great mystery of our Mother Nature."

A dual relation of Blavatsky to science remained unchanged, in

Hammer's opinion, throughout her theosophical career. It was manifested

also in the mahatma letters and later continued in The Secret Doctrine.

In one of the letters, terms and theories of the conventional science

are characterized with words such as "misleading", "vacillating",

"uncertain" and "incomplete".

It is this last word that is most important, that is, "science is a

half-truth." The Theosophical doctrine "not so much" denies the truth of

science, how much condemns its inability to explain an essence of the spiritual processes that "are supposedly the real causes" of the physical and chemical phenomena.

According to Hammer, "The Secret Doctrine" is completely "imbued with

the rhetoric of scientism". Although the "basic cosmological" concept in

this work ultimately derives "from ancient wisdom" that was received by

Blavatsky, as she claimed, from her "Masters," many of the details of

this declassified cosmology are accompanied by references to

archaeological discoveries, modern biological theories such as

evolutionary theory of Haeckel,

etc. She believed that the positioning of Theosophy in relation to

science is of great importance, and the third parts of both the 1st and

2nd volumes of her book have the common heading Science and the Secret Doctrine Contrasted.

These sections are devoted both to the refutation of the conventional

science, and to the search in it the support of occult teachings.

Blavatsky repeatedly returned to the assertion that modern physical

sciences point to the same reality as the esoteric doctrines:

"If there is anything on earth like progress, Science will some day have to give up, nolens volens, such monstrous ideas as her physical, self-guiding laws—void of soul and Spirit,—and then turn to the occult teachings. It has done so already, however altered are the title-page and revised editions of the Scientific Catechism."

Blavatsky generally did not reject science, suggesting the possibility of "reconciliation" of science and Theosophy.

She believed that they have "important common grounds", and that the

"weaknesses" of the traditional science are only its "temporary

shortcomings." The main point of contact, which unites science and

"occultism" against the common enemy, a dogmatic religion, was the

refusal to recognize "unknowable, absolutely transcendent causes."

Theosophical cosmos appears and disappears in an infinite sequence of

"cycles of evolution and involution." This is pantheistic position, because the beginning of this process does not require "transcendent God." Hammer has cited:

"Well may a man of science ask himself, 'What power is it that directs each atom?' [...] Theists would solve the question by answering 'God'; and would solve nothing philosophically. Occultism answers on its own pantheistic grounds."

Theosophical criticism

In

his thesis Arnold Kalnitsky wrote that, criticizing science of the 19th

century, the Theosophists claimed on the "futility" its attempts to

adequately explain "the greatest enigmas" of Universe. They evaluated

the "occult based" hypotheses as more accurate than those presented by

science.

Hammer wrote Blavatsky defined her position regarding science "from the beginning of her theosophical career." Thus, the Mahatma Letters

contain, in his opinion, the "rather unsystematic" accusations the

modern science and the fragments of the occult doctrine, supposedly "far

superior" the scientific ideas of the day. The essence of Blavatsky's

"later argument" is anticipated in the next passage from letter No. 11:

"Modern science is our best ally. Yet it is generally that same science

which is made the enemy to break our heads with." She constantly condemned the traditional science as "limited, materialistic and prejudiced" and blamed in this the famous thinkers and scholars. Bacon

was the first among the culprits "due to the materialism of his method,

'the general tenor' of his writing and, more specifically, his

misunderstanding of spiritual evolution." Newton's materialist error allegedly consisted in the fact that in his law of gravitation

the primary was the power, not the influence of the "spiritual causes."

In addition, she repeated the baseless, according to Hammer, assertion

that Newton came to his ideas after reading Böhme.

An American author Joseph Tyson wrote that, according to

Blavatsky, the mechanistic science's adepts of her time were the

"animate corpses." She wrote that "they have no spiritual sight because

their spirits have left them." She called their hypotheses "the sophisms suggested by cold reason," which future generations would banish to the "limbo of exploded myths." Also Henry Olcott proclaimed that the Theosophists must break "the walls of incredulous and despotic Western science."

Some scientists, according to Blavatsky, were more prone to

spiritual, and she "selectively approved" them. "The positive side of Descartes' work" was supposedly his faith in the "magnetic doctrine" and alchemy, although he was a "worshipper of matter." She was admired by Kepler's method, "combining scientific and esoteric thought."

She gave also some excerpts from Newton's most "speculative" works,

where he supports a "spiritualized" approach to gravity. Thus, according

to her words, these "greatest scientists" rediscovered the esoteric

knowledge already available to "Western occultists including Paracelsus... kabbalists and alchemists."

A religious studies scholar Alvin Kuhn wrote Blavatsky claimed in The Secret Doctrine

that occultism does not combat with conventional science, when "the

conclusions of the latter are grounded on a substratum of unassailable

fact." But when its opponents try "to wrench the formation of Kosmos...

from Spirit, and attribute all to blind matter, that the Occultists

claim the right to dispute and call in question their theories." She

stated that "science is limited" to researching one aspect of human life

that relates to the sphere of material nature. "There are other

aspects" of this life—metaphysical,

supersensory, for the knowledge of which science has no tools. Science

devotes its strength to the study of vital forces, which are expressed

in a phenomenal or sensual area. Consequently, it sees nothing but the

residual effects of such forces. "These are but the shadow of reality,"

Blavatsky claimed. Thus, science deals "only with appearances" and hints

of life, and that is all that it is capable of until the postulates of

the occult are recognized. Science is tied to "the plane of effects",

but occultism is take to "the plane of causes." Science "studies the

expression of life", esotericism sees life itself. So that the scientist

can learn "the elements of real causality", he will have to develop in

himself such abilities

which today almost all Europeans and Americans absolutely lack. There

is no other way to get enough facts to substantiate his conclusions.

Tim Rudbøg wrote in his thesis: "A large part of Blavatsky's

critique of modern science consisted in the critical view that many of

these so-called new discoveries and theories were actually known to the

ancients, but lost to the moderns due to their arrogance. In other

words, any 'new' discovery was, to a large extent, simply 'old wine in

new bottles'."

Theosophical evolutionism

Modern Theosophy, as professor Nicholas Goodrick-Clarke stated, "adapting contemporary scientific ideas," raised the concept of "spiritual evolution through countless worlds and eras." According to professor Donald Lopez, the occult "system of spiritual evolution" was more profound and advanced than that proposed by Charles Darwin. Theosophists accepted his theory but rejected the assertion that life originated from matter, and not from spirit.

Kuhn wrote that, according to Blavatsky, between the spiritual

evolution of man and his physical development "there is an abyss which

will not be easily crossed by any man in the full possession of his

intellectual faculties." Physical development,

"as modern Science teaches it, is a subject for open controversy;

spiritual and moral development on the same lines is the insane dream of

a crass materialism."

Darwinian theory and the materialistic science suggest that the

development of matter in an organic form leads to the emergence of the

psyche and intelligence as the products of two elements: matter and

energy. Occultism claims that such a process can lead to the creation of

physical forms only. Instead of considering intellect and consciousness

as properties of evolved organisms, Theosophy speaks of a "spiritual

evolution" as a concomitant biological one and associated with it.

"Evolution in its higher aspect" can't be explained if its factors are

reduced to blind material forces arising under the impact of the

"mechanical influences of environment."

An American author Gary Lachman

wrote that, according to Blavatsky, the "scientific" theory of

evolution reflects only that part of it that takes place in our present

physical world. Darwinism

does not take into account what happens before and after. In her

opinion, Darwin "begins his evolution of species at the lowest point and

traces upward. His only mistake may be that he applies his system at

the wrong end." After passing through the period of necessary

separation, the spirit returns to itself enriched during its journey.

Consequently, the biological evolution is not a "random" event that

could "occur" due to some "rare" combination of chemical matters and

then continued driven by the need for survival and suitable mutations. Blavatsky claimed that, not spirit is in matter, but on the contrary, matter "clings temporarily to spirit."

Thus, the spirit (or consciousness) is primary, and matter is a

temporary means used in its "work." According to Theosophy, evolution is

the basic phenomenon of the Universe that does not coincide with the

materialistic vision, which, in Blavatsky's opinion, is "a hideous,

ceaseless procession of sparks of cosmic matter created by no one... floating onward from nowhence... and it rushes nowhither." She proposed the kabalistic scheme of evolution: "A stone becomes a plant; a plant a beast; a beast a man; a man a spirit;

and the spirit a god." In this scheme: "Each perfected species in the

physical evolution only affords more scope to the directing intelligence

to act within the improved nervous system."

According to words of Dimitry Drujinin, Olcott claimed,

"Theosophy shows the student that evolution is a fact, but that it has

not been partial and incomplete as Darwin's theory makes it." Professor Iqbal Taimni

wrote that, it is not known to science that the main goal "of the

evolution of forms" is to obtain more effective means for the

development of the mind and "unfolding consciousness." This barbarism is

quite standard because the ordinary scientists decline to view

everything that is "invisible" and can't be investigated "by purely

physical means." Occultism allows one to obtain the "missing knowledge"

and makes the concept of the evolution of forms not only more complete,

but also explains the cause of the entire process, without which it

seems completely meaningless.

Orientalists and Theosophists

In 1888, the president of the Theosophical Society Henry Olcott met in Oxford with Max Müller, "the father of the 'Science of religion'," as Lopez named his.

Olcott wrote later in his diary that professor Müller, in a

conversation with him, highly appreciated the work of Theosophists in

translating and re-publishing the sacred books of the East. "But as for

our more cherished activities," Olcott wrote, "the discovery and spread

of ancient views on the existence of Siddhas and of the siddhis in man, he was utterly incredulous." In Müller's opinion, nor in the Vedas, nor in the Upanishads

there are any esoteric overtones announced by the Theosophists, and

they only sacrifice their reputation, pandering "to the superstitious

belief of the Hindus in such follies." In response to Olcott's attempt

to argue his point of view by references to the Gupta-Vidya and Patanjali

the professor said, "We had better change the subject." The president

has remembered well not only this conversation, but also "two marble

statuettes of the Buddha sitting in meditation, placed to the right and left of the fireplace." He noted this fact, having written in his diary in brackets: "Buddhists take notice."

Professor Lopez claimed that this was a significant meeting, because both, Buddhist Olcott, and the Buddhist studies

scholar Müller, although both were directly related to Buddhism,

nevertheless took different positions and lived in different worlds. The

world of Olcott, an American emigre and convinced Theosophist "no

formal training in the classical languages of Buddhism", but who was

knowing well both the Buddhist world, and many reputable monks, collided

with the world of Müller, a German emigre and outstanding sanskritologist, who was reading "Buddhist manuscripts in the original Sanskrit and Pali,"

and however failed to recognize theirs esoteric meaning and "never

traveled beyond Europe." In Asia, Olcott faced with Buddhist

superstition, which is why he argued with some of the leading monks of

Sri Lanka. But he deeply revered the Buddhist mores. After his travels

through the countries of Asia, he knew that for Buddhists it was

absolutely unacceptable and offensive to place anything connected with dharma on the floor [or even on a chair]. Moreover, he knew that Buddhists "would never place a statue of the Buddha on the floor."

Olcott asked all the same of the origin of these statuettes and

inquired about their placement. Müller answered that "the statues of the

Buddha" standing on the floor near his fireplace were taken out of "the

great temple of Rangoon (presumably the Shwedagon)."

The professor was so imbued with the British imperialism, as Lopez

noted, that he was not at all embarrassed to use the military trophies

captured in the Buddhist temple. The "more interesting" was Müller's

answer to the question why he put the Buddha statues on the floor:

"Because with the Greeks the hearth was the most sacred spot." According

to Lopez, the answer "sounds slightly disingenuous, but its implication

is important." For Müller, the image of the Buddha, captured in Asia

and taken to England, has ceased to be Asian, and therefore its owner

was not obliged allegedly to follow the "Asian custom." For him, the

Buddha became part "of European culture, like a Greek god," and

therefore he should follow the customs of Western civilization.

Five years after the meeting with Olcott, professor Müller published an article Esoteric Buddhism,

in which he tried again, in a different form, to prove that there is no

esotericism in Buddhism and never was. All his indignation the

professor directed against Blavatsky, believing that the Buddhist

esotericism is only her invention. "I love Buddha and admire Buddhist

morality", Müller wrote, "that I cannot remain silent when I see his

noble figure lowered to the level of religious charlatans, or his

teaching misrepresented as esoteric twaddle." Theosophists often disagreed with the European Orientalists and ridiculed their limitation. In 1882, in his letter to Alfred Sinnett mahatma Kuthumi offered, "Since those gentlemen—the Orientalists—presume to give to the world their soi-disant translations and commentaries on our sacred books, let the theosophists show the great ignorance of those 'world' pundits, by giving the public the right doctrines and explanations of what they would regard as an absurd, fancy theory."

Occultists and sceptics

For Hindus, the supernatural powers of a person, who was specially trained, aren't something special. Professor Radhakrishnan noted that in Indian psychology "the psychic experiences, such as telepathy and clairvoyance, were considered to be neither abnormal nor miraculous."

Kuhn wrote that, in Blavatsky's opinion, to consider magic

as a deception is to offend humanity: "To believe that for so many

thousands of years, one-half of mankind practiced deception and fraud on

the other half, is equivalent to saying that the human race was

composed only of knaves and incurable idiots." However, according to the Theosophical Masters, the "recent persecutions" for alleged witchcraft, magic, mediumship

convincingly show that the "only salvation" of the genuine occultists

lies in the public skepticism, because the attribution to the

"charlatans and the jugglers" securely protects them.

A member of the Russian Academy of Sciences, Eugene Alexandrov, argued that paranormal phenomena does not exist. He wrote, "There is no telepathy (a transmission and reading of thoughts), there is no clairvoyance, levitation is impossible, there is no 'dowsing', there is no phenomena of a 'poltergeist', there is no psychokinesis." As Edi Bilimoria

wrote, a typical Western scientist does not distinguish (or cannot

distinguish) two things: a "map" (the scientific model of the world) and

"territory" (Nature).

"Occult or Exact Science?"

A religious studies scholar Arnold Kalnitsky wrote that in this work Blavatsky outlines her "typical" views about science.

- Statement on impotence of science

Kalnitsky wrote that at the beginning of her article, Blavatsky

distinguishes "modern science" from "esoteric science", and argues that

the methodology of the latter is preferable because it ultimately has a

more practical, solid basis. He cited the passage from hers article:

"Every new discovery made by modern science vindicates the truths of the archaic philosophy. The true occultist is acquainted with no single problem that esoteric science is unable to solve, if approached in the right direction."

He concluded Blavatsky considers modern science to be a form of the

"archaic philosophy", which, as a synthesized worldview, includes the

"esoteric science." According to her, this is the position of the "true

occultist," who can solve any problem by the proper use of esoteric

methodology.

Blavatsky criticizes, Kalnitsky noted, the perspective of modern

science, by disagreeing with the idea that the manipulation of matter

presents a real scientific challenge. She asserts that replacing the

word "matter" with the term "spirit"

would result in a greater goal. She tries to show that knowledge of

mere matter is not enough to provide the answers sought by science,

because such knowledge does not adequately explain even the simplest

phenomena of nature. Blavatsky notes that spiritualistic phenomena,

with which she claims her audience would be well familiar, show the

need for revising the prevailing scientific consensus. She argues that

there is another form of "proof" of the existence of extrasensory abilities, citing the example of the use of narcotics, which allegedly had facilitated the demonstration of such abilities. Blavatsky's statement on "natural phenomena" is quoted in Kalnitsky thesis:

"No doubt the powers of human fancy are great; no doubt delusion and hallucination may be generated for a shorter or a longer period in the healthiest human brain either naturally or artificially. But natural phenomena that are not included in that 'abnormal' class do exist; and they have at last taken forcible possession even of scientific minds."

Recognizing the potential errors inherent in relying upon

imagination, and the unreliability of "delusion and hallucination,"

Blavatsky is still trying to gain the "stamp of legitimation" from

reputable scientific judgement that could confirm that supersensory

abilities "do exist." It was a constant aim of Theosophy, though

implicit, and it was accompanied always by a distrust to the scientific

approach. On the one hand, Blavatsky gives occasion for a reconciliation

with the scientists, on the other—continues to denounce them.

In Kalnitsky's opinion, she demonstrates a desire to show that the

scientific evidence of the extrasensory perception is quite possible:

"The phenomena of hypnotism, of thought-transference, of sense-provoking, merging as they do into one another and manifesting their occult existence in our phenomenal world, succeeded finally in arresting the attention of some eminent scientists."

Kalnitsky stated Blavatsky shows a dualistic approach in her

interpretation of these phenomena, distinguishing between "their occult

existence" and their manifestation "in our phenomenal world."

Apparently, this means that there is noumenal

"sphere of reality," which is the basis of the phenomenal world.

Furthermore, the assertion that "some eminent scientists" had shown

interest in various forms of ESP, obviously, indicates that most

scientists are not interested in it, and that widely recognizing of

their paranormal nature did not happen. In particular, she criticizes

the findings of the doctor Charcot

and some other scientists in France, England, Russia, Germany and

Italy, who "have been investigating, experimenting and theorising for

over fifteen years." This is quoted in work by Kalnitsky:

"The sole explanation given to the public, to those who thirst to become acquainted with the real, the intimate nature of the phenomena, with their productive cause and genesis—is that the sensitives who manifest them are all hysterical! They are psychopates, and neurosists—we are told—no other cause underlying the endless variety of manifestations than that of a purely physiological character."

- Scientific method's limitation

Kalnitsky wrote that, in Blavatsky's opinion, the scientists, who are trying to explore the controversial paranormal phenomena,

find themselves in a situation of utter helplessness, but it is not

their fault. They simply do not have an appropriate set of conceptual

"tools" for the right approach to these phenomena. Without an elementary

familiarization with occult principles and the adoption, at least as a

working hypothesis, the notion of the subtle worlds

of nature, the science is not able to reveal the true depth and scope

of the universal laws that underlie all cosmic processes. The orthodox scientists-materialists

are constrained by the limitations of their sciences, and so they need a

new orientation based on the attraction of occult knowledge. However,

according to Blavatsky, even admitting the legitimacy of the occult

hypothesis, they will not be able to bring their research to the end:

"Therefore, having conducted their experiments to a certain boundary, they would desist and declare their task accomplished. Then the phenomena might be passed on to transcendentalists and philosophers to speculate upon."

Turning to the consideration of conflicting opinions about the

paranormal experience, Blavatsky says that the scientific recognition of

the hypothesis about the nature of the psychic

phenomena is not excluded, but it requires a discussion in relation to

their underlying causes. She also claims that to defend the Theosophical

position harder than spiritualistic, because the Theosophists

categorically reject as a materialist theory so and a belief in spirits,

presented in a traditional spiritualistic approach. Blavatsky

classifies the spiritualists as the "idealists" and the scientists—as

the "materialists," who both fully convinced that modern science can,

respectively, or to confirm, or to deny the authenticity of the kingdom

of the spirits. But those who believe in the ability of a science to

accept the occult presentation will be disappointed, because its modern

methodology simply does not allow it. Kalnitsky has quoted:

"Science, unless remodelled entirely, can have no hand in occult teachings. Whenever investigated on the plan of the modern scientific methods, occult phenomena will prove ten times more difficult to explain than those of the spiritualists pure and simple."

He wrote that Blavatsky believes that modern scientific methods need

to be rethought and remodeled to make it possible to study phenomena

that can not be adequately explained from the materialistic standpoint.

She expresses her disappointment with the existing state of affairs,

doubting in achieving any progress. After ten years of a careful

monitoring of the debate, she does not believe in the possibility of an

objective and impartial investigation of the paranormal phenomena, not

to mention the real revision of the well-established scientific views

and the adoption of more adequate occult theory. The few scientists who

could believe in the authenticity of such phenomena do not accept the

hypothesis beyond the spiritualistic representations. Even in the midst

of doubt of the truth of the materialist worldview, they are unable to

move from spiritualism to the occult theory. In the study of unexplained

side of the nature their respect for the traditional scientific

orthodoxy always prevails over their personal views. Thus, according to

Blavatsky, a necessary condition of objectivity is the impartiality and a

change of the opinions.

In Kalnitsky's opinion, considering the methodology of science, Blavatsky understood that the inductive reasoning, based on data supplied by the physical senses, can not adequately provide a reliable way to study the abnormal phenomena. He has quoted:

"Science—I mean Western Science—has to proceed on strictly defined lines. She glories in her powers of observation, induction, analysis and inference. Whenever a phenomenon of an abnormal nature comes before her for investigation, she has to sift it to its very bottom, or let it go. And this she has to do, and she cannot, as we have shown, proceed on any other than the inductive methods based entirely on the evidence of physical senses."

- Against ethical materialism

Kalnitsky wrote Blavatsky argues that the fruits of materialistic

scientific worldview, reaching the sphere of practical interests of the

people, shape their ethics.

She sees a direct logical connection between a faith in the soulless

mechanistic universe and by the fact that is for her as a purely

egoistic attitude to life. He has quoted:

"The theoretical materialistic science recognizes nought but substance. Substance is its deity, its only God." We are told that practical materialism, on the other hand, concerns itself with nothing that does not lead directly or indirectly to personal benefit. "Gold is its idol," justly observes Professor Butleroff (a spiritualist, yet one who could never accept even the elementary truths of occultism, for he "cannot understand them"). – "A lump of matter," he adds, "the beloved substance of the theoretical materialists, is transformed into a lump of mud in the unclean hands of ethical materialism. And if the former gives but little importance to inner (psychic) states that are not perfectly demonstrated by their exterior states, the latter disregards entirely the inner states of life... The spiritual aspect of life has no meaning for practical materialism, everything being summed up for it in the external. The adoration of this external finds its principal and basic justification in the dogma of materialism, which has legalized it."

Kalnitsky wrote Blavatsky clearly expresses her utter contempt for

the values of "practical materialists." She accuses the ideological

foundations of theoretical materialism for its an ignoring of the

spiritual dimension of reality. This aversion to the complete

unspirituality of the materialism reflects her "implicit gnostic

ethical stance." A materialistic-physical and selfish interests are not

compatible with the idealised world of the spirit and the

transcendental purpose of mystical

enlightenment. The practical materialists, even professing adherence to

a moral code, do not cease to be by ethical materialists. According to

Kalnitsky, "Blavatsky's radical gnostic dualism is allowing no room for

compromise or alternative options." Thus, she considers the esoteric

vision of reality the only viable alternative.

Kalnitsky wrote that science was seen in the West as the dominant

category of knowledge and for the Theosophists it was not so an enemy,

as a potential ally. However, the stereotypes of the materialistic

thinking were one of the main obstacles to the esoteric representation

of reality. Thus, at every opportunity Blavatsky tries to dispel what

was for Theosophy, as she considered, alien and wrong. It is meant to

challenge to many of the basic principles that supported the

materialistic basis of science. However, a neutral and objective

approach of the science to the analysis of the facts seemed, for the

Theosophists, trustworthy. Blavatsky's striving to apply this approach

to the consideration of the paranormal and mystical phenomena pursued a

goal: to achieve the legitimacy and public acceptance of Theosophy. A

skeptical position, which was taken by Blavatsky in respect of the

materialistic science, was motivated by her outrage over the ignore by

the scientists the spiritual dimension of reality. On the other hand,

the assertion that spiritual truths can be proven from a scientific

point of view, was a constant theme of Blavatsky's claims. The efforts

of the Theosophists were focused on the legitimation of all forms of

extrasensory and mystical experience.

Theosophical psychophysiology

A few years after Blavatsky's death, the "second generation" of the Theosophists came to the leadership of the Theosophical Society.

As Hammer wrote, during this period, the "foci" of the Theosophical

scientism shifted from the theory of evolution to other areas of

science. Charles Webster Leadbeater, who became "the chief ideologist" of the Society, had involved with Annie Besant

in the study of a functioning of the human mind. A religious studies

scholar Gregory Tillett wrote that, according their claim, the

functioning of mind "extrudes into the external world" the thought-forms

which can be observed using clairvoyance methods. In 1901 Besant and Leadbeater published a book named Thought-Forms: A Record of Clairvoyant Investigation

contained a lot of color illustrations of forms, "created," according

to its authors, by thoughts, emotions, and senses of men, as well by

music. They argued that main source of the forms is the aura of man, the outer part of the cloud-like substance of his "subtle bodies," interpenetrating each other, and extending beyond the confines of his physical body.

Theosophical chemistry

According to Hammer and other scholars, in parallel with the "psychophysiological"

researches, the Theosophists were busy an occult chemistry based on a

"greatly modified" atomic theory. Leadbeater began "the occult

investigation" of chemical elements as early as 1895, and Besant soon

joined him. They argued that, using clairvoyance, can describe the

intra-atomic structure of any element. In their words, each element

composed of atoms containing a certain number of "smaller particles."

They published "these and other results" in 1908 in a book Occult Chemistry: Clairvoyant Observations on the Chemical Elements.

Hammer wrote, "Although Leadbeater was the principal clairvoyant, the

enduring interest in... chemistry is probably due to Annie Besant's

fascination with science, especially chemistry."

Theosophy and physics

A historian of religion Egil Asprem informed that in 1923, an astronomer and Theosophist G. E. Sutcliffe published a book Studies in Occult Chemistry and Physics which was a "critical analysis" of the theory of relativity.

The author has pursued the goal: to equalize the meaning of "Eastern"

and "Western science", describing their "as two complementary

'schools'." In this book, the theory of relativity is regarded as the

highest achievement of "Western science," whereas the results of the

Theosophical study "of atoms and etheric structures" known as "occult

chemistry" are presented as the achievement of "the 'Eastern' school".

In an effort to show that the results of occult research can be

compared with the theory of relativity, Sutcliffe "proposes a wholly new

theory of gravity," based on physics of ether.

From his reasoning it can be seen that he is thoroughly erudite in the

Theosophical literature, while also having a background in "conventional

physics from Britain" in the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th

century. Sutcliffe tries to reinterpret the theory of Albert Einstein in "a tradition of British anti-relativism", operating with the liberal "concept of ether."

The concept of Sutcliffe is based on "contraction and expansion of the

accompanying ether of bodies," so, according to him, gravitation "is one

of the effects of an expanding sphere of ether," and the electrical

phenomena are a function of the "contracting sphere."

Professor Taimni wrote that the theory of relativity apparently

gave "a new direction to our civilization" and created problems that

"are a challenge" to our current worldview and ways of thinking. In the

"scientific circles" it is considered that if mathematics is used to

prove something, then the question "is finally settled", and it can't be

discussed. However, most such conclusions are not always based on

proven assumptions, and this makes possible a mistake in "the final

conclusion." Often one does not take into account the fact that

mathematical inference can then be correct if he accepts into account

"all factors" concerning this issue, and if it is not, the conclusion

may be incorrect "or only partially correct." This should be borne in

mind when considering the nature of space and time, as well as the

Einstein's method used to solve this problem. He based his theory "only

on facts of the physical world" and if there are other, more subtle worlds "besides the physical",

and they exist in accordance with the occult, then his theory has no

authority "with respect to those worlds." Since his theory is based only

on physical facts, it can be true, at best, "only for purely physical

phenomena." It can't be assumed that it reveals the nature of space and

time "in general", because it is presented "to the human mind"

functioning within the boundaries of "the physical brain." "The very

fact that the concept of the time-space continuum"

given in his theory is too difficult for the human mind, indicates its

limitations. In fact, its author simply tried to interpret "imperfectly

the shadows of some realities cast on the screen in a shadow play of the

mind."

Taimni wrote that anyone who closely studied the nature of space

and time could be convinced that the human mind is "also a very

important factor in this problem", therefore, to understand the space

and time, it is necessary to take into account this factor. And since

the human mind is not only what is manifested through its physical

brain, but has "many degrees of subtlety and modes of expression," the

entire human nature is "really involved in the problem" of space and

time. And therefore only the one who "dived" into his consciousness and

has "unraveled" his deepest secrets, having reached the source from

which space and time come,

is really capable of saying what the true nature "of these basic

realities of the universe is." "Who is more competent to pronounce a

correct opinion about the nature of an orange," Taimni is asking, "he

who has merely scratched the rind or he who has peeled the orange and

eaten it?"

According to words of Kuhn, Blavatsky claimed, "It is on the

doctrine of the illusive nature of matter, and the infinite divisibility

of the atom, that the whole science of Occultism is built." The researchers in esotericism Emily B. Sellon and Renée Weber have written:

"Anticipating the conclusions of Einsteinian relativity and field theory, as well as quantum mechanics, Blavatsky proposed a universe in which billiard-ball atoms and push-pull forces were replaced by space, time, motion, and energy, yielding a picture of a dynamic universe far in advance of her time."

New paradigm

According to a philosopher and religious studies scholar Vladimir Trefilov, the modern Theosophists

were among the first who attempted to create "a new paradigm of

thinking through the synthesis of scientific and non-scientific

knowledge." As professor of Buddhist studies and Buddhist Evgeny Torchinov

said, "Discussion between physicists, philosophers, psychologists, and

scholars of religious studies in order to find the solutions of a

problem of the general scientific paradigm change, the isomorphism of consciousness and physical world, and even the ontology of consciousness in general could well take place, if don't resort to sticking labels like 'mysticism'." Professor Stanislav Grof,

psychologist, wrote that Western science has raised matter to a status

of the prime cause of Universe, reducing life, consciousness, and mind

to the forms of its accidental products. Dominance in Western science a paradigm of Newton-Descartes became one of the causes of the emergence and development of the "planetary crisis."

An Ukrainian philosopher Julia Shabanova

has believed that "the post-materialist scientific paradigm and the

worldview idealism" should become a conceptual basis of the future

civilization. The Russian cyberneticist Sergei Kurdyumov and philosopher Helena Knyazeva, in a book Laws of Evolution and Self-organization of Complex Systems,

suggested that the "paradigm of self-organization and non-linearity"

would become the basis of the new scientific paradigm, taking from the

West "the positive aspects of the tradition of analysis", and from the

East—ideas of the integrity, cyclicity, and the one law for Universe and man.

"Eastern ideas about the universal coherence, the unity of everything in the world, and the cyclic flowing into each other of Non-Being and Being (unmanifested and manifested) can resonate with the synergetic models... We can assume that there is a kind of an origin environment, in which all other observable and studied environments have grown. Then all the environments, with which we are dealing in life and scientific experiment, appear as some fluctuations (disturbances), the visible to us manifestations (modifications) of this one substrate—the origin environment."

According to a historian of religion Egil Asprem, an Indian scientist and engineer Edi Bilimoria

was one of the most significant characters "in the Theosophical

discourse on science of the last decade and a half." In his work Mirages in Western Science Resolved by Occult Science

he confirms the division into "Western" and "occult" science which took

place already at the time of the formation of the Theosophical Society,

and also "conceptually" updates the discussion of "modern physics and

cosmology." Playing back the well-known Theosophical "rhetoric,"

Bilimoria suggests to move forward to "a reconciliation and reuniting of

the wise old parent, Occult Science, with its adolescent prodigal son,

Western science."

"Occult science is not bent on toppling, but rather on uplifting Western science to an even nobler position, by using examples from Western science itself to show how it is rooted in the deeper substratum of Occult Science and Philosophy."

Criticism of Theosophy

A Russian philosopher Vladimir Solovyov wrote that modern Theosophy is a doctrine not only "anti-religious" and "antiphilosophic", but also "anti-scientific." A religious philosopher Sergius Bulgakov stated that [Blavatskian] Theosophy, trying to replace religion with itself, turns into a "vulgar pseudoscientific mythology." In Berdyaev's

opinion, modern Theosophy does not represent a synthesis of religion,

philosophy and science, as its adherents say, but there is a "mixture"

of them, in which there is no real religion, no real philosophy, no real

science.

The ambiguous attitude of the Theosophists towards science was

especially abruptly criticized by the servants of the Christian church. In 1912, John Driscoll, an author of The Catholic Encyclopedia, has described Theosophy's attitude to science as follows:

"Modern theosophy claims to be a definite science. Its teachings are the product of thought, and its source is consciousness, not any Divine revelation. [...] Judging it as presented by its own exponents, it appears to be a strange mixture of mysticism, charlatanism, and thaumaturgic pretension combined with an eager effort to express its teaching in words which reflect the atmosphere of Christian ethics and modern scientific truths."

A Russian theologian, Andrey Kuraev,

accused the Theosophists of violation of the principles of scientific

aethics, arguing they do not react to the opponents' objections, do not

bring "a scientific arguments in support of their position", and also

put themselves "beyond all criticism from side of science." In support

of his words, Kurayev quoted Blavatsky's statement on the need to fight

with "every modern scholar's" pretension to evaluate "of ancient

Esotericism", when he is not "a Mystic" or "a Kabalist".

In connection with the special attention of the Theosophists to the

theory of evolution, a Russian Orthodox cleric and theologian Dimitry

Drujinin wrote that "Theosophy began to parasitize on the central

tendencies of thought and science of its time." And also: "The rough and

cheeky Blavatsky's criticism of Darwinism turned into personal insults

to scholars." According to Drujinin, "the statements of Theosophy are an

absurd nonsense." Lydia Fesenkova, an employee of the Institute of philosophy,

also severely criticized the occult statements of Blavatsky, which

described anthropogenesis: "From the point of view of science, such

beliefs are an explicit profanity and don't have the right to exist in

the serious literature."

An academician Viacheslav Stepin answering the question about pseudoscience

said, "The dominant value of the scientific rationality begins to

influence other spheres of culture—and religion, the myth are modernized

often under this influence. On the border between them and science

arise the parascientific concepts, which are trying to find a place in the field of science."

Theosophists-scientists

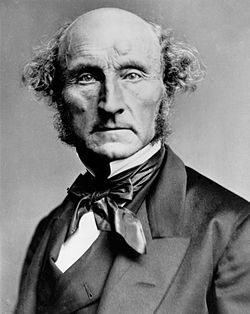

- William Crookes (1832 – 1919), a British chemist and physicist.

- Frederic Myers (1843 – 1901), a British philologist and philosopher.

- George Mead (1863 – 1933), a British historian and religious studies scholar.

- Lester Smith (1904 – 1992), a British chemist (F.R.S.).

- Alexander Wilder (1823 – 1908), an American religious studies scholar and philosopher.

- William James (1842 – 1910), an American psychologist and philosopher.

- Thomas Edison (1847 – 1931), an American engineer and inventor.

- Robert Ellwood (born in 1933), an American religious studies scholar, expert on world religions.

- Camille Flammarion (1842 – 1925), a French astronomer and writer.

- Émile Marcault (1878 – 1968), a French psychologist and philologist.

- Charles Johnston (1867 – 1931), an Irish Sanskrit scholar and orientalist.

- Iqbal Taimni (1898 – 1978), an Indian chemist and philosopher.

- Edi Bilimoria (born in ...), an Indian scientist and engineer (FIMechE, CEng, EurIng).

- Julia Shabanova (born in ...), an Ukrainian philosopher and pedagogist.

Interesting facts

- The Theosophists-scientists, who were awarded Subba Row medal: George Mead (1898), Émile Marcault (1936), Iqbal Taimni (1975), Lester Smith (1976).